THE FIN-DE-SIÈCLE AND BELLE ÉPOQUE

Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen 1850–1917 and Alessandro Panizzardi DATES UNKNOWN

Homosexuals have at times been figures of scandal, and have been placed on trial, because of prohibitions against homosexual acts and solicitation. They have faced imprisonment and public shame, on some occasions so great as to ruin careers or lead to suicide. In other instances, they have been drawn into political scandals where sexuality was not of central importance, but yet entered into the public consciousness – scandals involving treason, for instance. The Dreyfus case provides an illustration.

The Dreyfus Affair involved charges in 1893–94 that a Jewish captain in the French army had been selling military secrets to a German official: espionage and treason. A military court convicted Alfred Dreyfus and sent him to prison on Devil’s Island, the ‘tropical hell’ of a French colony in South America. Despite efforts by family and supporters, he was reconvicted when the case went to appeal. Only after several more years was it proven that some of the documents used to convict Dreyfus had been forgeries, and that another person had been providing the secrets to the Germans. Dreyfus was eventually exonerated. For a decade, the case divided France between two camps bitterly debating the place of Jews, the honour of the military, and France’s international reputation. Anti-Semitism, not surprisingly, played a large part in proclamations of Dreyfus’ guilt.

There was a little-known homosexual side to the story. The initial memorandum used to indict Dreyfus was found by a cleaner in the rubbish bin of Captain Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen, a military attaché at the German embassy in Paris. Born in 1850 in Potsdam, the aristocratic Schwartzkoppen had served in the Westphalian infantry, and fought in the 1870–71 war in which Prussia dealt an ignominious defeat to the French. In the early 1890s, he took up the sensitive post in Paris.

Schwartzkoppen’s counterpart at the Italian embassy was Alessandro Panizzardi. Probably unknown to most associates, because of their great discretion, was the fact that Schwartzkoppen and Panizzardi were engaged in an affair. However, in addition to the document used against Dreyfus, the French secret agents working in the German embassy also discovered letters from the Italian to Schwartzkoppen. Panizzardi wrote in slightly fractured French, sometimes signing himself ‘Alexandrine’ in letters to ‘my dear friend’ ‘Maximilienne’ (in the female form), or ‘my little dog’. Panizzardi expressed his eagerness for meetings, cooing, ‘Am I still your Alexandrine? When are you going to come to bugger me … I’ll come soon so you can bugger me anywhere. A thousand salutations from her who loves you so much.’ One letter made a vague reference to a ‘dangerous situation for me with a French officer’, and a passing remark about maps of Nice that this ‘scoundrel D.’ had given him.

‘D.’ turned out not to be Dreyfus, but his prosecutors nevertheless felt that they had turned up useful evidence. Complicit officials compiled a dossier falsely suggesting that a homosexual circle including Schwartzkoppen and Panizzardi, and extending to Spanish and American attachés, was involved in espionage. The prosecutors did not make the information public, since they thought the revelations indecent. They also feared the effect that disclosure would have on French relations with Italy, which were growing uneasy because of Italy’s alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary. Furthermore, there had been riots against Italian migrants in France in 1893, and in 1894 an Italian anarchist had assassinated the French president. The prosecutors did, however, submit the secret dossier to the military tribunal (without sharing it with Dreyfus’ lawyers), which inspected it in camera with some distaste.

Jews and homosexuals were both regarded with suspicion: they were considered sexually predatory and vice-ridden, but also effeminate and unmanly, lacking in bravery and honour. They were thought to be deracinated, potentially traitorous and criminal. The Dreyfus Affair, which unfolded in a country still chafing from military defeat and worried about its declining birth rate, posed challenges to established sexual and gender roles and contributed to a general crisis of French manhood. Revelations about two homosexual military attachés would have shocked the public, and to the court-martial panel even an indirect link between homosexuals and Jews could not but reinforce notions of moral and military danger to la patrie. One scholar has suggested that the guilty verdict imposed on Dreyfus represented not only a punishment of French Jews, but in some ways struck a surrogate blow against homosexuals.

There was a further homosexual twist to the complex Dreyfus Affair. Panizzardi, upset at Dreyfus’ conviction, since he knew from Schwartzkoppen the real identity of the spy who had sold French documents, contacted a friend named Carlos Blacker, a wickedly handsome Englishman in Paris. Blacker was also a friend of Oscar Wilde (his best friend, according to some). Panizzardi and Blacker discussed releasing information to the press to show that Dreyfus was innocent, while presumably also taking care to ensure that Panizzardi’s and Schwartzkoppen’s identities (and their relationship) remained hidden. Wilde and Blacker had fallen out when Wilde briefly took up with Lord Alfred Douglas after his release from prison, but they were reconciled in Paris when Wilde claimed that he and Douglas had parted company. At that juncture Blacker told Wilde about Panizzardi’s revelations. He subsequently fell out again with Wilde, who had importuned him for money. But the Dreyfus-related information was now in circulation. Wilde passed it on to Chris Healey (also homosexual, and the lover of a correspondent for the Observer and the New York Times), and Healey, in turn, gave it to Émile Zola, from whom it was transmitted to the press. Publication of an anonymously signed article in a Paris newspaper in 1898, soon after Zola was convicted for his J’accuse attack on the anti-Dreyfusards, set in train the process that eventually led to Dreyfus’ release and pardon.

Neither Schwartzkoppen nor Panizzardi seems to have suffered permanent damage. Their correspondence shows no shame or fear of repercussion over their relationship. In 1896 the Italian did break with the German, explaining enigmatically that ‘an unsurmountable barrier will rise up between you and me’. Among later correspondence discovered by the French was a letter from a woman with whom Schwartzkoppen was sexually involved, a liaison that may have precipitated the rupture (though Panizzardi knew that Schwartzkoppen was bisexual). Panizzardi continued in his career, and a photograph taken in 1899 shows him as a debonair mustachioed and bemedalled officer; by the time of the First World War he had attained the rank of general. Schwartzkoppen, also much pained by Dreyfus’ conviction, returned to Germany, where he served in the First World War and died of wounds in 1917.

If there is any figure in the history of homosexuality who needs no introduction, it is Oscar Wilde. The patron saint of modern homosexuals, Wilde has occupied an unrivalled place in the pantheon of gay lives. Wilde is many things: raconteur, poet, novelist, playwright, man-about-town, celebrity, Irish nationalist and victim. Those multiple facets of his personality explain his continuing appeal: he is the subject of biographies, memoirs, plays and films; the British Library’s catalogue lists 1,419 works under the keywords ‘Oscar Wilde’; and a Google search turns up some 6.5 million links (Walt Whitman manages fewer than 3 million).

Wilde was born in Ireland in 1854. As the son of a prosperous surgeon, he enjoyed a background of bourgeois comfort, but his mother supported Irish nationalism, neatly placing him within the paradoxes of Victorian life. Wilde’s provocation of society began very early, when as a child he was baptized twice: once into the Anglican Church of Ireland – his father’s denomination – and then, several years later, as a Roman Catholic, at his mother’s insistence.

Wilde studied at Trinity College, Dublin, and then went on to read Classics at Magdalen College, Oxford, between 1874 and 1879. It was a time when Hellenism, and the homosexual expression integral to classical culture, suffused Oxford, inspiring Walter Pater’s theory of ‘art for art’s sake’ and the celebration of male sociability and affection. Wilde cultivated a flamboyance that, both at Oxford and afterwards, contributed to his fame and would be mimicked by many ‘camp’ homosexuals for years to come. He sought and won celebrity in the drawing rooms and theatres of London, and during a wildly successful year-long tour of America delivered 150 lectures on topics ranging from Irish poetry to the decorative arts. Wilde travelled to other countries as well: he visited Baron von Gloeden in Sicily (like many other homosexuals), fixed up André Gide with a native bedpartner in North Africa, and frequented the beau monde in Paris. His ‘posing as a somdomite’ (as the Marquess of Queensberry, father of Lord Alfred Douglas, misspelled the accusation) foreshadowed what postmodernists call ‘the performance of sexuality’.

Like many eminent Victorian homosexuals, and those of other eras, Wilde was married (to Constance Lloyd) and had children (two sons, Cyril and Vyvyan), but his homosexual tastes were manifest and protean. He felt attraction to men of all types and backgrounds – strong soldiers, Arab boys, the tousled-headed but feckless young aristocrat ‘Bosie’, and the gentle Canadian Robert Ross. He transgressed boundaries of sexual desire and of age and class.

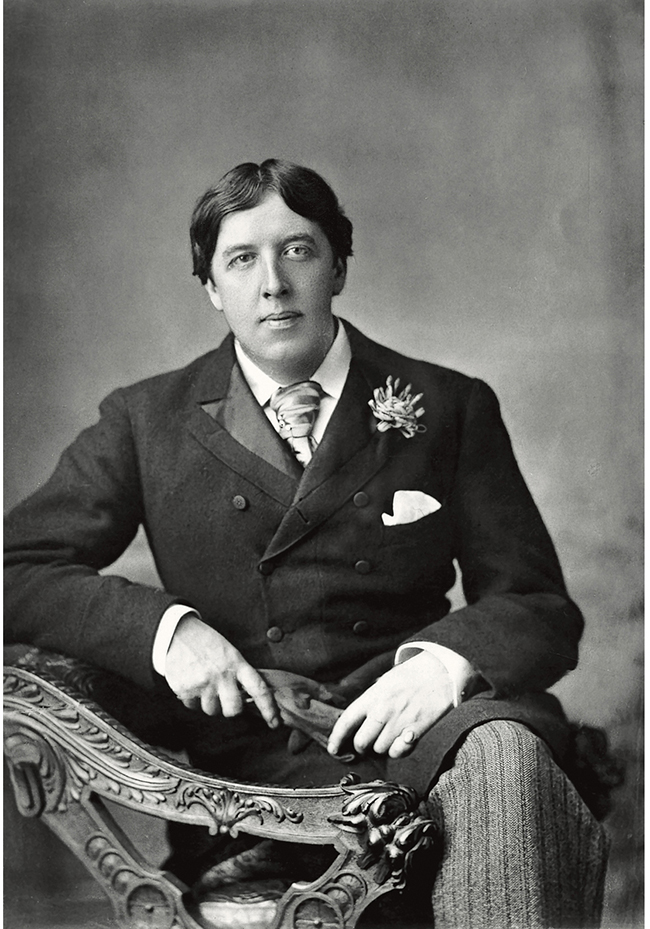

Oscar Wilde, c. 1891 (National Portrait Gallery, London)

As is well known, in 1895 Queensberry’s allegation prompted Wilde to take out a warrant for criminal libel. At the Old Bailey, evidence of Wilde’s frequentations led to Queensberry being found not guilty. Subsequently Wilde was arrested for offences under the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act, which had extended buggery legislation to criminalize any sexual acts between men. Wilde’s oft-quoted words at his trial deserve to be repeated yet again, for they gave his loves a genealogy – the gay lives of antiquity and the Renaissance: ‘“The love that dare not speak its name” in this century is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep, spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art … It is in this century misunderstood, so much misunderstood that it may be described as “the love that dare not speak its name”, and on that account I am placed where I am now. It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an elder and a younger man, when the elder man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so, the world does not understand. The world mocks it, and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it.’

The world – or at least the British court system – did put Wilde in prison. After his release, his health and spirit broken, he wandered around the Continent for three years. He died in a shabby hotel in Paris in 1900, in his last moments, and with a final burst of wit, famously remarking that either the wallpaper or he had to go. The room, minus the wallpaper, is preserved in his memory and can be rented at an eyewatering rate.

Wilde was a literary phenomenon, and his works almost get lost in the personality cult. The repartee of comedies such as Lady Windermere’s Fan (1892) and The Importance of Being Earnest (1895) pokes fun at the conventions of British life. Salomé (1891; originally written in French) remains a shocking representation of the biblical heroine–villain who demands the head of John the Baptist. The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), arguably the most famous novel of its time, paints a darker portrait of vice and its rewards. His essay ‘The Soul of Man under Socialism’ (1891) suggests an aesthetic approach to anarchism, while The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1898) offers a meditation on life and death, man and his fate, and the tragedy of crime and of punishment.

Wilde’s martyrdom is of great importance. Arrest, scandal, conviction and ignominy loomed as the possible fate for men in Britain, Germany, the United States and other countries where homosexual acts were illegal, and where even the finest words about love, the ancients and natural desires could not convince constables, jurors and legislators. The spectre of the dapper Wilde wearing tattered convict-clothes, the clever Oxonian on the treadmill of forced labour, haunted homosexuals.

Wilde shows up in gay culture around the world: both Yukio Mishima in Japan and Ugra in India, for instance, invoked him in their writings. An apposite quotation from Wilde’s work (not to mention a well-placed lily) in the early decades of the 20th century indicated – to those who could read the signs – membership of the homosexual fraternity. One of the first openly gay bookshops in the world, opened in New York in 1967, took Oscar Wilde’s name; and on the internet, the curious can still hear a scratchy recording of his creaky voice reading from The Ballad of Reading Gaol. He is memorialized in a rather lurid statue (‘the fag on the crag’, as Dubliners have affectionately dubbed it) in Merrion Square, near the house where he was born. The tomb in Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris where Wilde’s remains were transferred in 1909 – in the presence of his son and Robbie Ross, faithful friend and former lover, whose own ashes would be buried there, too – seldom lacks for a flower, or a visitor cheerfully photographing and reverently touching the monument. Since 1998 Londoners have Maggi Hambling’s memorial, a bench-like sculpture in Adelaide Street where passers-by can sit to chat with Wilde, whose shoulders and head (smoking a cigarette, with consummate political incorrectness) rise as if from a coffin, or a bed, or perhaps (to paraphrase Wilde) just from the gutter, looking at the stars.

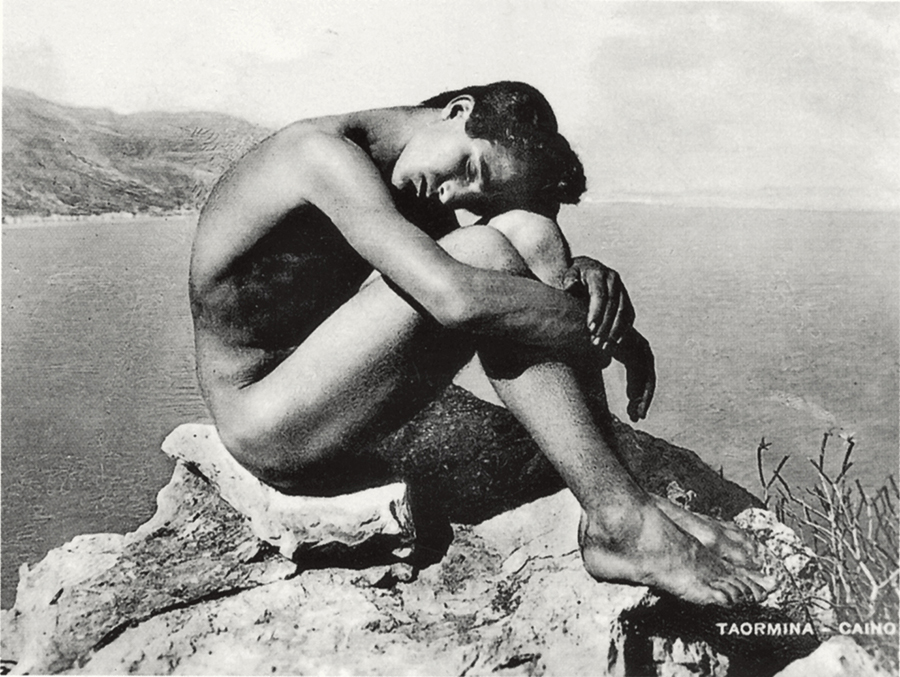

Victorians knew Wilhelm von Gloeden for his photographs, often distributed as postcards, of Italian landscapes and genre scenes, shaded courtyards and picturesque peasants. He is now known primarily for the countless shots of naked Sicilian youths collected in albums destined for a gay audience. Although these seem quaint to the modern eye, von Gloeden remains the most important homoerotic image-maker of the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Born in northern Germany in 1856, von Gloeden moved to Italy as a young man, hoping the warm climate would cure his tuberculosis, and he took up photography as a hobby. Financial need turned the avocation into a profession, and the new market for picture postcards provided him with an income. He lived in Taormina until his death (except during the Great War, when he was forced, as an enemy alien, to leave Italy). The town is one of the most beautiful sites in Sicily: its hilltop houses looking over a well-preserved Greek theatre, the peak of Mount Etna and the ‘wine-dark’ Mediterranean. Taormina’s residents were modest fisherfolk and artisans, but von Gloeden helped turn their town into a tourist attraction, visited by the kings of England, Spain and Siam, the German Kaiser, Eleonora Duse, Richard Strauss and Oscar Wilde.

Taormina provided the young men who posed for von Gloeden. Most stripped off their clothes, though the photographer sometimes costumed them with a mock toga or crowned them with a wreath of leaves. A few were perilously young, but the majority were ephebes, teenagers displaying the attributes of sexual maturity. Some pictures are stiff tableaux vivants of antique or modern Mediterranean life, and the occasional one exhibits a cheeky sexual innuendo. Others are simply portraits of shapely young men standing before the camera.

Von Gloeden’s pictures provoke interest for several reasons. They embody an ideal of the beauty of Mediterranean youth that stretches back to antiquity. That ideal was revived in the work of Johann Joachim Winckelmann, father of art history, Enlightenment traveller to the Mediterranean, papal librarian, and victim of a rough male partner who murdered him in Trieste. Winckelmann saw statuary of the classical Greek male as the epitome of both beauty and artistic accomplishment. Male beauty, antique and contemporary, drew many visitors to the Mediterranean in the 19th century, and in Northern Europe Hellenists such as Walter Pater, working in Oxford in the late 1800s, promoted the Platonic vision of truth and beauty (even when colleagues applied real and metaphorical fig-leaves to the Classics). Von Gloeden’s young men incarnated the ideal; even if they sometimes look a bit grubby, these ragazzi are dark-headed, finely muscled and seductive gods. This image of Mediterranean manliness remained the recurrent dream of many classically educated homosexuals until the early 20th century and beyond. Physical and emotional longing mixed easily with a romanticized nostalgia for the ancient world, where such desires flourished, and Italy had a special resonance as the place where sexual and cultural tourism went hand in hand.

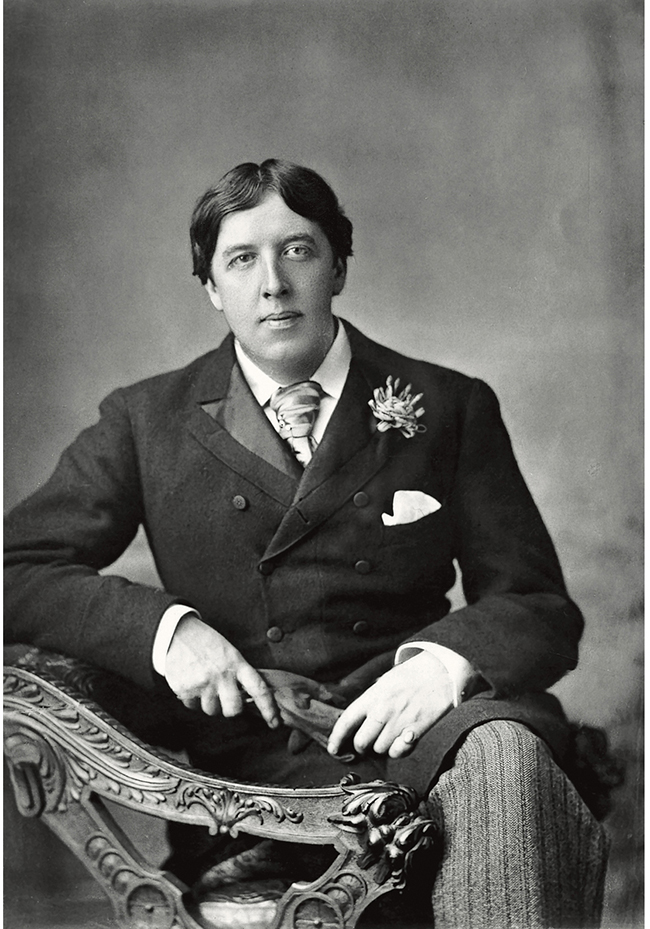

Wilhelm von Gloeden, Cain, c. 1902 (Photo Wilhelm von Gloeden)

Von Gloeden’s experiences also make us wonder how he did what he did. After all, posing dozens of near-naked young men around the gardens of a small town in a Catholic country might have proved a provocation to the locals. Von Gloeden and his faithful major-domo Pancrazio Bucini (‘Il Moro’, the dark one) apparently organized trysts that went well beyond the exigencies of photo sessions. Under different conditions, von Gloeden could have been indicted as a pornographer, a sodomite or possibly a paedophile. Homosexual acts, however, were not criminal in Italy; von Gloeden seems to have been a generous patron (he established bank accounts for some models and set up several young men in business); and his fame attracted tourists to Taormina. Perhaps the mises en scène of peasants and fishermen as classical heroes proved flattering to local sensibilities, and the youths probably enjoyed strutting around for the friendly foreign man and his new-fangled picture-taking apparatus. Southern mores, preserving the Madonna-inspired chastity of young women while encouraging expressions of male virility and camaraderie, allowed space and time in a young man’s life for erotic games of the sort that von Gloeden played.

If von Gloeden’s photos now appear risible to those accustomed to a more raw and explicit form of imagery, it is easy to forget the subtle ways in which they questioned the attitudes of their time. Villagers in Sicily, regarded even by many Italians as a wild, savage place, were cast as the inheritors of the classical world. Antique settings made homosexuality – sin, crime and illness, to moralizing contemporaries – noble. The idyllic outdoor compositions of ordinary adolescents and seaside landscapes made ‘unnatural’ desires look very natural. Taormina was far removed from the dens of urban depravity associated in the common view with homosexual vice. The easy comradeship of boys with their arms thrown around friends’ shoulders, or lounging together on a terrace, suggested a utopia of happy and affectionate bonding, not the sordid backstreet couplings denounced in the yellow press. The gamut of ages in von Gloeden’s pictures suggested the dawning of sexual awareness in adolescence and earlier. The full-frontal exuberance of the models presents an image of sexuality that in the hands of some of von Gloeden’s contemporary painters and photographers looked coy and abashed. Even if they are often pseudo-classical, the themes of his pictures allude to artistic conventions – the figure study, the ages of man, the Three Graces, the odalisque, bathers, the good Samaritan, a haloed saint, mythological characters – that set him within the curriculum of art history. His most famous image, echoing a painting by Hippolyte Flandrin, shows a boy sitting on a rock with his head on his knees; it offers an existential statement about youth, sexuality and the individual in the world.

Other photographers, such as Vincenzo Galdi and Guglielmo Plüschow, imitated von Gloeden, but their work was more blatantly pornographic. Some of their images no doubt served as tourist brochures, and the Mediterranean pilgrimage that had begun before von Gloeden continued. The German industrialist Friedrich Krupp and the French writer Jacques d’Adelswärd-Fersen were denizens of Capri, Italy’s other homosexual hideaway, while John Addington Symonds and A. E. Housman formed liaisons with gondoliers. Thomas Mann’s fictional Aschenbach met his death in Venice, even if the lad he longed for, Tadzio, was a blond Pole rather than a swarthy Italian.

Wilhelm von Gloeden, Self-Portrait as Christ, c. 1904 (Raimondo Biffi Collection)

Von Gloeden and Il Moro lived a contented life in Taormina; only after the German’s death did Fascists destroy many of his photographic plates. By that time, other venues for homosexual fantasy beckoned, but the Mediterranean had occupied the centre of the homosexual map for centuries, the place where, it was hoped, antique statues came to life and the quest for beauty found its fulfilment. The reality in the technicolour landscape might be less romantic – an impecunious young man bargaining pleasure for a few coins – yet no other travelogue proved so seductive.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in early 20th-century European culture. His troupe reinvigorated an effete, moribund art form and became great celebrities of the age. But his reach extended far beyond the world of dance: Diaghilev introduced exotic Russian themes to the West and contributed to burgeoning interest in Orientalism, primitivism and a revival of classical motifs. The Ballets Russes had an immense influence on the visual arts, bringing together a star-studded ensemble of composers and artists – Stravinsky, Picasso and Cocteau, among the most famous – in the process contributing to the birth of modernism. In terms of gender, Diaghilev’s works challenged stereotypes and elevated the male dancer to the central role previously occupied by women. The homosexual ethos of the impresario’s circle, both dancers and audience, made the Ballets Russes a vital arena of gay life.

Diaghilev came from the provincial gentry. His was an aspirational and cultured family, which would lose its wealth (earned from vodka distilleries) through financial mismanagement. Sergei studied law at the University of St Petersburg, travelled widely in Europe – calling on Oscar Wilde in London – and in 1898 set up a pioneering journal, Mir iskusstva (‘World of Art’). This established Diaghilev as a promoter of culture, although he was also a writer and composer in his own right. Diaghilev gained entry to the tsar’s court and organized art exhibitions in the Russian capital and, later, in Paris. He gained appointment as an administrator at the Imperial Theatres, which managed the Bolshoi in Moscow and the Mariinsky in St Petersburg – a role that sparked his interest in ballet.

Before long Diaghilev turned from ballet administrator to impresario, and decided to take a troupe of Russian dancers to Paris. After several years of preparation, the Ballets Russes arrived in 1909, presenting a season of works that showed off Russian culture, abstract-style choreography and the principals’ dancing prowess.

Although a financial drain, these first performances in Paris scored an enormous triumph. The poet Anna de Noailles summed up the effect: ‘It was as if Creation, having stopped on the seventh day, now all of a sudden resumed.’ Over the next twenty years, the troupe performed annually in Paris, London and other capitals, and also toured the Americas. The Ballets Russes became the most important ballet company in the world, presenting some traditional works but specializing in provocative new pieces – such as The Rite of Spring, which, with its innovative dance vocabulary and avant-garde music by Stravinsky, ignited a riot in Paris in 1913. Later works, such as the first Cubist ballet, Parade (1917), which boasted sets by Picasso, a libretto by Cocteau and music by Erik Satie, continued the company’s flair for confrontational brilliance.

Diaghilev filled his private life with handsome young men – dancers, choreographers and assistants who became his lovers. Although his father had taken him to a prostitute for sexual initiation, Diaghilev was exclusively attracted to men. Despite homosexual acts being criminal in tsarist Russia, the upper echelons of society proved tolerant of such proclivities, and his circle included many homosexuals, such as the poet Mikhail Kuzmin, who like Diaghilev cruised around St Petersburg’s parks and artistic salons for cadets and students. Diaghilev’s first lover was his wealthy cousin and the co-editor of Mir iskusstva, Dmitry Filosofov. Their relationship ended after a decade when Diaghilev learned that Filosofov was trying to steal his own current lover-on-the-side; Diaghilev made a scene in a restaurant, but parted with Filosofov in tears when he left for France. He then marked time sexually with a new companion, Aleksei Mavrin, whom he took for a honeymoon to the Mediterranean.

Diaghilev’s meeting with the 17-year-old Vaslav Nijinsky in 1907 provided him with a new lover and gave the Ballets Russes its greatest star; he would become the world’s leading male dancer. It was a former partner, Prince Pavel Lvov – homosexual, aristocratic and artistic circles were intimately linked – who passed Nijinsky on to Diaghilev. Count Harry Kessler, a homosexual habitué of the ballet, remarking on Nijinsky’s extraordinary agility and strength in soaring above the stage, wrote that he was like ‘a butterfly, but at the same time he is the epitome of manliness and youthful beauty’. Nijinsky was now the focus of both Diaghilev’s private and professional activities. Diaghilev required loyalty from his protégés, however, and when Nijinsky unexpectedly married in 1913 Diaghilev was left distraught and bitter, dismissing him from the company.

Soon Diaghilev found another budding dancer, the darkly seductive 18-year-old Léonide Massine. Kessler again commented: ‘Nijinsky was a Greek god, Massine a small, wild, graceful creature of the Steppes.’ Soon they were cavorting on a trip to Italy. Less dramatically gifted as a dancer than Nijinsky, Massine became the much-applauded chief choreographer for the Ballets Russes. Although bedded by Diaghilev, he went his heterosexual way in 1921 (he, too, was sent packing from the ballet company). Next for Diaghilev came an affair with another teenager, Boris Kochno – a former lover of the composer Karol Szymanowski who would later have a fling with Cole Porter. Diaghilev’s interest eventually waned, even if they continued to work together. His new flame was a tall, elegant English dancer who performed under the name Anton Dolin; Lydia Lopokova, one of Diaghilev’s dancers and John Maynard Keynes’ future wife, noted succinctly: ‘Shadow of Oscar Wilde’. Then came another grand dancer and choreographer, Serge Lifar, also young and beautiful. (‘I don’t like young men over twenty-five,’ Diaghilev conceded.) Diaghilev’s last ‘official’ lover was Igor Markevitch, a sweet 16; he subsequently earned a reputation as composer and conductor, and married one of Nijinsky’s daughters.

Leon Bakst, Portrait of Sergei Diaghilev and his Nanny, 1906 (Russian Museum, St Petersburg)

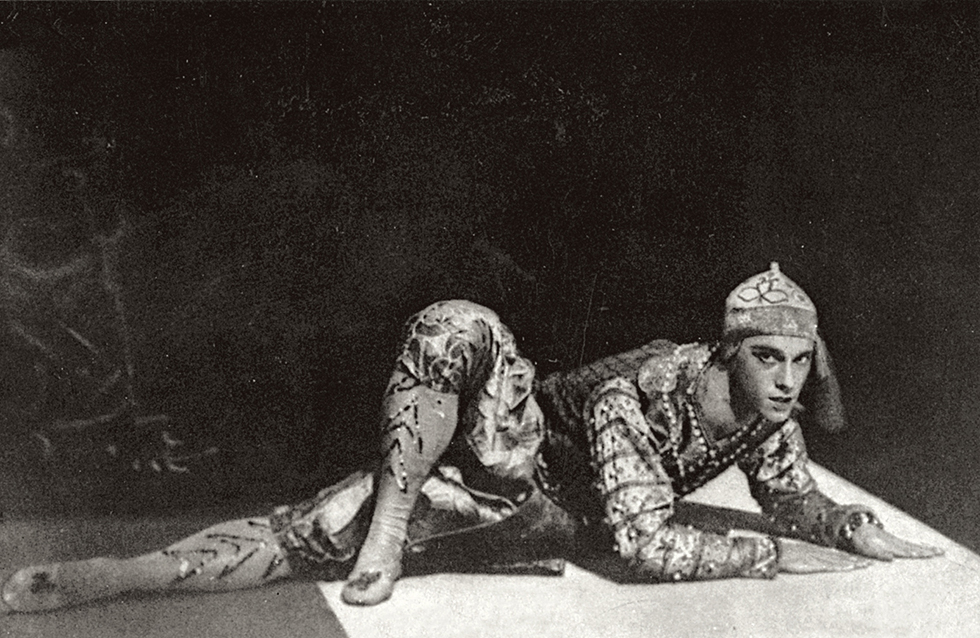

Vaslav Nijinsky performing in Les Orientales, 1910 (Dansmuseet, Stockholm)

Diaghilev died in Venice during a holiday with Markevitch; Lifar and Kochno soon arrived to pay their tribute. Nijinsky was mentally ill, suffering from the schizophrenia that would confine him to clinics until his death in 1950.

Diaghilev’s loves were central to his life and to that of the Ballets Russes. Those who attended performances also appreciated the dancers. The gay Bloomsbury artist Duncan Grant painted pictures of the performers and enshrined a photo of Nijinsky on his mantelpiece; and Keynes admitted that he first attended the Ballets Russes to ‘view Mr Nijinsky’s legs’. Homosexuals such as Cocteau, Ravel and Reynaldo Hahn flocked around the company for artistic stimulation and for the homoerotic pleasures of its ambiance.

The Ballets Russes’ productions were sexually charged, and often homoerotic. Early in his career, the Bolshoi had dismissed Nijinsky for wearing a too-revealing costume, and his later outfits showed off his fine body ever more than was common in ballet. In the notorious L’Après-midi d’un faune (1912), Nijinsky, clad in a tight bodysuit, mimed masturbation on the scarf of a paramour. In Schéhérazade (1910), one of the most famous of Diaghilev’s creations, Nijinsky’s rather feminine-looking costumes and camp movements bent expectations of gender; other performances showed him off varyingly as masculine or androgynous. Narcisse (1911) presented the ancient story of the hunter who fell in love with himself, and ballets featuring sailors played on a homosexual obsession of the time. Writing about a seduction scene featuring two girls and a young man in Jeux (1913) – a ballet set on a tennis court that he choreographed – Nijinsky revealed how ‘Diaghilev wanted to make love to two boys at the same time and wanted these boys to make love to him … I camouflaged these personalities on purpose.’ Few productions passed up on the chance to reveal the physiques of such dancers as Massine and Dolin, making the Ballets Russes a very gay spectacle.

Jacques d’Adelswärd-Fersen 1880–1923

Jacques d’Adelswärd-Fersen (or simply ‘Fersen’, as he sometimes signed himself) was blessed by the gods. Tall and slender, with a shock of blond hair, he personified a type of handsome elegance. His pedigree was grand, and he had the title of baron, though he later promoted himself to count. A Swedish nobleman in his ancestry had been Marie-Antoinette’s lover. His paternal grandfather had served in the Paris constituent assembly of 1848 (and briefly gone into exile with Victor Hugo), and was the founder of a steelworks in Longwy, in Lorraine, while an ancestor on his mother’s side founded the Paris newspaper Le Soir. Fersen was wealthy, having inherited a fortune from the Lorraine factories. He was well educated in the best Parisian lycée, and briefly continued his studies at the elite École des Sciences Politiques and at the University of Geneva. He was also talented, in his short life publishing almost twenty novels and books of poetry. He lived luxuriously in a Paris apartment near the Arc de Triomphe, and in a clifftop mansion he had built on Capri.

Fersen’s life incarnates several key aspects of gay history. He was a dandy who moved in a cosmopolitan and cultured homosexual milieu of the Belle Époque. He ran afoul of the law, and was sentenced to six months in prison for inciting youth to debauchery. Like many homosexuals of the time, he experienced the magnetic attraction of Italy and the East. He edited the first French literary journal to treat homosexual themes, and his own writings evoke antiquity, aestheticism, exoticism and male loves.

Jacques d’Adelswärd-Fersen, c. 1900 (Raimondo Biffi Collection)

By the dawn of the 20th century, when he was only in his early twenties, Fersen had already published a Conte d’amour (1898), Chansons légères (1900), L’Hymnaire d’Adonis, à la façon de M. le Marquis de Sade (1902), and a book on Venice, Notre-Dame des mers mortes (1902). A habitué of aristocratic salons, he also organized soirées at his residence, attended by members of Paris society, at which young men – students whom he recruited from secondary schools – dressed in mock classical garb for tableaux vivants, and where Fersen and others recited poetry. He also had sex with many of the boys – behaviour that brought him to the attention of the police and led to his arrest and sentencing on morals charges. The affaire Fersen, and the incarceration of the author and a fellow aristocrat, fed rumours of orgies and black masses; they filled the pages of Paris newspapers, which caricatured the manners and morals of these devotees of antiquity and young men. For good measure, in 1905 Fersen himself wrote a novel about the scandal, Lord Lyllian.

Once released from jail Fersen fled to Capri, which, along with Taormina in Sicily – where Fersen visited the photographer Wilhelm von Gloeden – was already becoming a mecca for those who found Italy more congenial than northern countries to their tastes. Fersen also travelled to Rome, where he met Nino Cesarini, a 15-year-old newspaper vendor who became his life-long companion. While Fersen’s Neoclassical Villa Lysis was being constructed on Capri, near the ruins of one of Tiberius’ palaces, he journeyed to Ceylon, where he discovered opium and became enamoured (in Orientalist fashion) of the mysteries of the East. He also found houseboys to bring back to Capri.

To present-day readers, Fersen’s writings are hothouse in style and feverish in emotion. The poems of Ainsi chantait Marsyas, published in 1907, are illustrative. The opening poem maps the lover’s body: ‘Warm breast on which opals fade / Armpit, golden vapours deep in light and shade / Burnished heels, sinewy calves, the odours of the male / Belly whence the rose incense stifles the voice that moans.’ A dedication to Nino vows: ‘Nothing can ever tear you from my arms / God himself could not unseal our lips … / You are my blood, you are my flesh, you are my fever! And you are the sole good which will never be taken from me.’ In a poem entitled ‘Nino’, ‘Your name is the light / And the blue sky / A ray of prayerful sun / In the depths of your eyes … / It is Italian languor / In a kiss / Around which my soul agonises … / It is the soft and sweet perfume / Of the death of flowers.’ Other poems fear the loss of the beloved – one is a vicious text explicitly inscribed to a woman who had been pursuing Nino – or the loss of beauty with the ravages of age. Alcibiades and Antinous are summoned, and the landscapes of Italy and Asia invoked, in the celebration of love and its lingering memory.

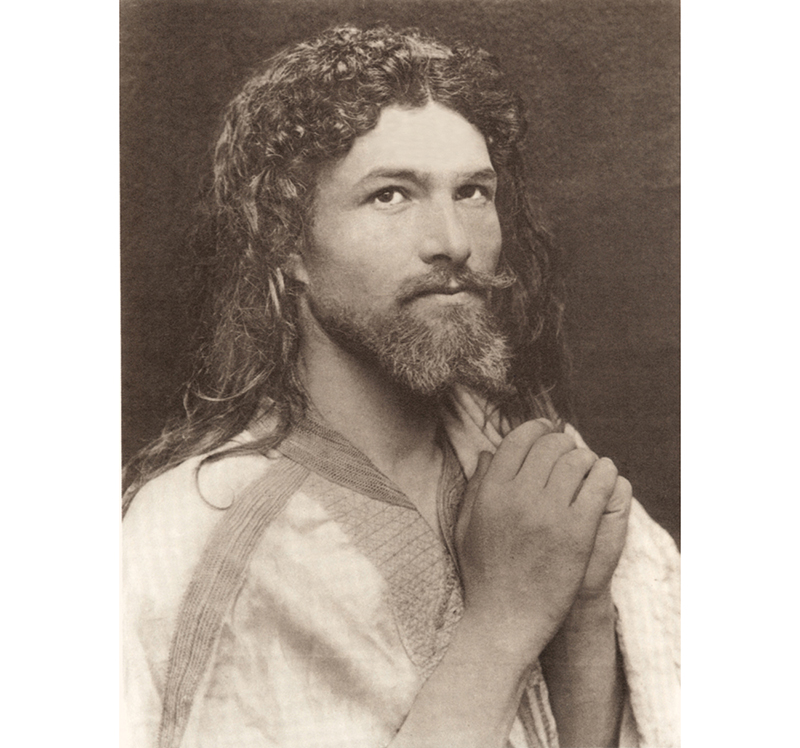

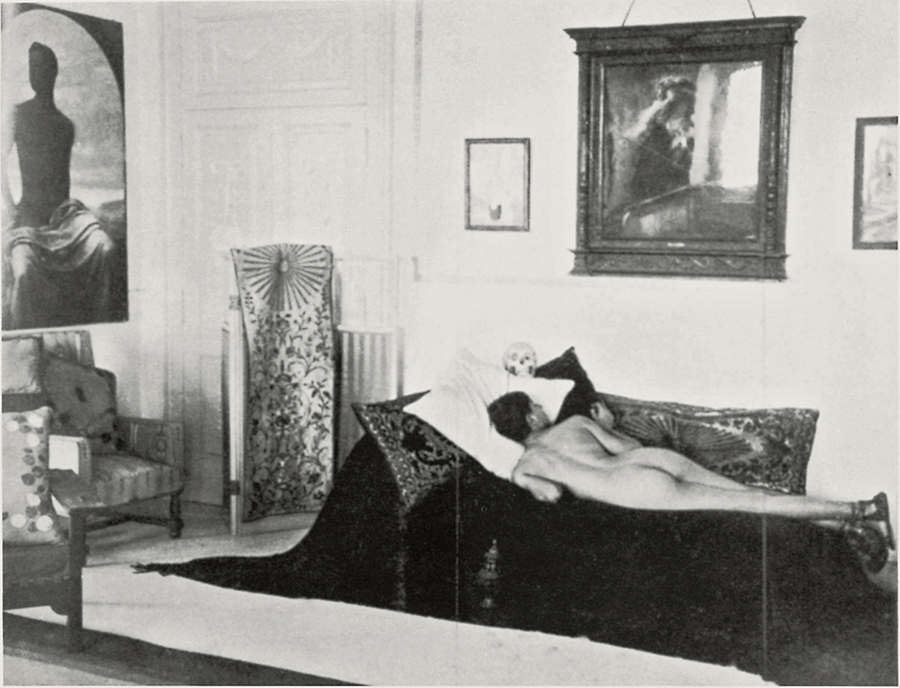

Nino Cesarini in the Villa Lysis, photographed by Wilhlem von Plüschow, c. 1906 (Photo Wilhelm von Plüschow)

Few authors dared to voice their homosexual sentiments as clearly as Fersen. And relatively few would write a novel such as Et le feu s’éteignit sur la mer (1909), in which a sculptor enamoured of Classics leaves his wife for a male companion, braving social opprobrium and Christian sanction: ‘For twenty centuries this monstrous doctrine of sacrifice prevailed by its cowardice in the face of imaginary tortures and the fear of a ridiculous hell.’

Fersen’s work merits rereading. Et le feu s’éteignit sur la mer offers mordant comic portraits of arriviste Americans, pretend Russian nobles, precious pedants, and what he called ‘tea-caddy’ Englishmen; and his overwrought poems nevertheless contain lines of great beauty. Fersen’s last work, Hei Hsiang (1921), with its evocation of China and India, its poems about Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas, and its description of ideal youths, is a testimony to a certain early 20th-century homosexual sensibility.

In Paris in 1909, Fersen began publication of a splendidly produced literary journal, Akademos, which he described as a monthly review of art and criticism. Although it managed only twelve issues, its articles included pieces on aestheticism, the renaissance of paganism, paintings of St Sebastian, the poetry of Sappho, and androgynous love; in addition there were translations of Javanese legends and Arabic poems. Artistic engravings of many comely men – the canonical Antinous and St Sebastian among them – underlined the review’s orientation, as did its contributors: the homosexual authors Georges Eekhoud and Achille Essebac, for instance, and luminaries such as the bisexual Colette.

Fersen weathered occasional attacks (his novel on Capri riled many local people), continuing to travel, write and entertain a Who’s Who of visitors to the Villa Lysis. His weakness was drugs, however – one room at the villa was set aside for opium-smoking, and he also used cocaine. His death – caused by a heart attack, according to autopsy reports – was probably provoked by an overdose of cocaine mixed into a glass of champagne, prepared during a meal with Nino after he had returned, ill, from Naples. In his poem ‘The Last Supper’, a clairvoyant Fersen foresaw the scene of an antique love in the modern world: ‘Pale, dazzled by the moon’s ardour / Which spreads through the heavens in mystic splendour / United for the last twilight on earth / On the edge of a Greek bay consumed in light / Here, marmoreal, the gods resuscitated …’. Fersen’s tomb overlooks the Bay of Naples, and his life was memorialized in Roger Peyrefitte’s novel L’Exilé de Capri (1959). Nino Cesarini, to whom Fersen left shares in the family steelworks, bank accounts and use of the house in Capri, died in Rome in 1943. The Villa Lysis is now a museum.

One of the most intriguing early 20th-century composers, Karol Szymanowski was born into the Polish gentry, growing up on his family’s estate in the Ukraine, where many Poles had settled after their country’s absorption into the Russian Empire. As well as speaking Polish, he learned Russian, French and German as a child, and studied music with his father and tutors before enrolling in a musical academy in Warsaw. While there, he became associated with the Young Poland group of intellectuals, who, greatly influenced by Symbolism, agitated for a revival in the Polish arts. Over the next few years Szymanowski travelled around Europe, returning to the family house to compose. Exempted from military service in the First World War because of a childhood injury that left him lame, he experienced some of his most creative years composing in the Polish countryside. The idyll would not last, however: with the arrival of the Bolshevik Revolution the family home was destroyed, and in the midst of violence and bloodshed Szymanowski and his family fled to Warsaw.

Szymanowski’s outpouring of works in the postwar years – concertos, settings for poems, symphonies, religious compositions – brought him fame in Poland and abroad, but his finances were never healthy, and sometimes dire. A period as director of the Warsaw Conservatory (1927–29), and as head of the Polish Academy of Music (1930–32), proved neither happy nor successful: there were conflicts with colleagues, and the Polish state was becoming increasingly authoritarian. Alcoholism and tuberculosis precipitated his death, in a Swiss sanatorium, at the age of 54. After a state funeral, he was buried in Kraków.

Although a proud Pole, Szymanowski espoused what he termed ‘pan-Europeanism’ – a type of cultured cosmopolitanism – and criticized the provincialism of compatriots and of the independent Poland that emerged in 1918. He was particularly drawn to Italy, where he had travelled regularly before the war, visiting Florence, Rome and other cities. His real magnet was Sicily: he was enamoured of the seaside town of Taormina and the antique ruins of Syracuse. The Islamic world and its culture also beckoned, prompting visits to Tunisia and Algeria, where he borrowed themes for his settings of erotic and mystic poems by Hafiz and Rumi.

Like many others of his age and inclinations, Szymanowski thus followed the pathway to the Mediterranean. The pianist Arthur Rubinstein recollected one conversation: ‘After his return he raved about Sicily, especially Taormina. “There,” he said, “I saw a few young men bathing who could be models for Antinous. I couldn’t take my eyes off them.” Now he was a confirmed homosexual, he told me all this with burning eyes.’

Although Szymanowski’s orientation is beyond doubt, there are few published details about his private life. From what we know, it seems that his most important relationship was probably his summer affair, during 1919, with Boris Kochno, a 15-year-old Russian with literary aspirations. Rubinstein quoted Szymanowski’s recollection: ‘I found the greatest happiness – I lived in heaven. I met a young man of the most extraordinary beauty, a poet with a voice that was music, and, Arthur, he loved me. It is only thanks to our love that I could write so much music.’ Owing to the chaos of warfare in Poland, they lost contact after the holiday; several later meetings in Paris were made awkward by Kochno’s new relationship with Sergei Diaghilev. Little is revealed about Szymanowski’s other loves. Alistair Wightman, the author of a 400-page biography of Szymanowski, acknowledges the composer’s sexuality but is coy about his emotional life, providing only tidbits: Szymanowski spent part of a trip to New York ‘in pursuit of’ a man the composer described as ‘the young (and beautiful) Lord Allington’; and in his last years, ‘a string of young men’ apparently came to his retreat in the Tatra Mountains, the ‘first of whom was the novelist Zbigniew Unilowski, who was passed off as the composer’s secretary’.

Szymanowski expressed his sexuality most clearly in a two-volume novel, The Ephebe, written soon after the First World War. It was never published: the manuscript remained in the hands of his friend (and sometime librettist) Jaroslaw Iwaszkiewicz, but was destroyed in the German bombing of Warsaw in 1939. In 1981 a Polish musicologist in Paris discovered some miscellaneous commentaries on the book, as well as one long chapter that Szymanowski had translated into Russian for Kochno. Several French-language poems that the composer had appended speak of his search for love and the pleasure he took in a young partner’s caresses, even in the face of social disapproval.

The surviving chapter of Szymanowski’s novel, finally published in 1993 in German, is a dialogue on homosexual and heterosexual love, with arguments advanced by a classically educated German nobleman and a Frenchman resident in Florence, who argues the superiority of love between men. The main protagonists in the full novel, as remembered by Iwaszkiewicz, are a beautiful young Polish prince and aspiring writer, and his companion, an older composer, the two characters representing different aspects of Szymanowski’s persona. The setting is Italy. In one section, called the ‘Tale of the Saintly Youth Enoch Porfiry, Iconographer’, a rebel artist creates a fresco for a Byzantine church that shows not a dying Christ but a handsome youth; he is killed by outraged priests, foreshadowing the duel between Christianity and antiquity in Szymanowski’s opera King Roger (1924).

The musicologist Stephen Downes has argued that Eros is a unifying theme in Szymanowski’s work. It appears most homoerotically in King Roger, the composer’s masterwork, which was influenced by his memories of Italy and his reading of Nietzsche, Walter Pater and Euripides. The opera is set in the early 12th century, at the court of King Roger in Sicily – a crossroads where Greek, Arabic, Latin and Norman influences blended. The work concerns the pull between Christian asceticism, represented as the opera opens by the grandeur of the Orthodox liturgy, and Dionysian hedonism, personified by a beautiful young shepherd – ‘My God is as beautiful as I,’ he tells the king. The queen and courtiers are seduced, but at the end of the opera Roger neither follows the shepherd nor returns to the world of tradition – even if his lyrical greeting of the sunrise nevertheless suggests a step towards personal emancipation. Szymanowski planned to readdress the conflict in another work, on the Renaissance sculptor Benvenuto Cellini; it was never written, although he summarized the scenario as one in which ‘mankind abandoned the harsh, cold churches, forgot about the scent of incense, about priestly psalmodies to find himself in the bright light of the sun, surrounded by beautiful figures’.