Gymnasts and swimmers feature in many of Eugène Jansson’s paintings, their presence revealing much about his personal life, the possibilities for homoerotic sociability in Scandinavia, and the potency of the fit body in the homosexual imagination.

Jansson was born in Stockholm, where he lived for the rest of his life. His background was petty bourgeois, but the death of his father, a concierge in the postal department, reduced the family’s circumstances. Jansson and his mother and brother moved to a working-class district on the heights of Stockholm, a location that afforded magnificent views of the city, stretching over the water to the sky. Jansson, who had studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts and had already won critical attention for his landscapes, began to paint brilliantly lyrical blue canvases of the Stockholm night, ‘nocturnes’ as he called them. Occasionally, factories or workers’ housing sit in the expanses, an indication of Jansson’s socialist politics (though such plebeian and modernist motifs did not endear him to collectors).

Around 1904, after a trip to Italy, Jansson changed themes. As a child, Jansson had suffered a bout of scarlet fever and other maladies that left him with partial deafness and enduring kidney problems; he had taken up physical exercise to restore his health and had become interested in athletics. Now gymnasts started to appear in his paintings, entirely naked men wrestling, hefting barbells or exercising on athletic apparatuses in elegantly minimalist wood-floored, whitewashed and sun-drenched rooms. Some of the images are rather grotesque: contorted gymnasts, hanging from rings, look like pieces of meat on butchers’ hooks. Others are more inviting, such as a 1907 picture of a nude athlete in a cruciform pose, framed by a door, perhaps beckoning a visitor into the room or forcing someone to brush past his body in order to enter. The model was in fact a long-term, intimate friend of Jansson, and the picture seemed to illustrate a comment made by a fellow artist in his elegy after Jansson’s death: ‘You searched for the beauty of the human body, pictured in all its vigour and the force of its youth.’

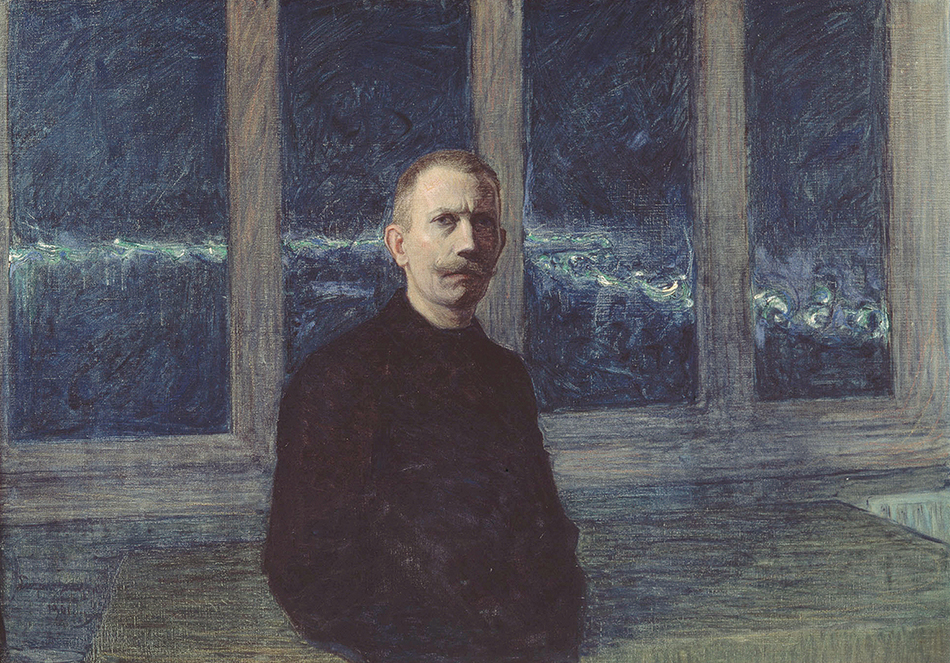

Eugène Jansson, Self-Portrait, 1901 (Photo Tord Lund/Thielska Galleriet, Stockholm)

Jansson set some of his works in the Swedish navy swimming baths in Stockholm. Again the men are naked, artfully lounging around the pool or gracefully diving into the water. Each figure is a study of a comely, slender sailor, unembarrassed at showing his buttocks or genitals, and happy to share the masculine camaraderie of the pool and to gaze on the prowess of others, hovering between water and sky in their dives. In one painting, Jansson has depicted himself among the nude swimmers, rather incongruously attired in a white suit, blue cummerbund, yellow tie and jaunty hat decorated in blue and yellow (the Swedish national colours). He was an accomplished swimmer, and he enjoyed frequenting the young sailors and swimmers, apparently giving them gifts or money in return for their companionship. Here he has literally painted himself into their company as visitor, patron and – though he faces out of the canvas, away from the swimmers – as voyeur.

Eugène Jansson, The Naval Bathhouse, 1907 (Photo Tord Lund/Thielska Galleriet, Stockholm)

Jansson’s athletes and swimmers radiate a kind of innocence, a comfort in their nakedness. They belong to the naturist fashions of the early 20th century, which preached the gospel of ‘a healthy mind in a healthy body’, and remind us of the Olympic Games that took place in Stockholm in 1912. They personify the health that Jansson did not enjoy, and perhaps the freedom that the introverted artist, who was obliged to care for a psychologically troubled mother, could never experience. They fit into a long history of homoerotic images of swimmers, and look forward to the California pool paintings of David Hockney.

Homosexual acts remained illegal in Sweden until 1944. Jansson’s brother, who was also homosexual, burned all of the artist’s papers after his death As is all too often the case with homosexual figures of the past, the documentation of his private life was thus destroyed. Jansson’s art is little known outside Scandinavia, and his works portraying athletes and swimmers proved unsettling to the general public during his lifetime, though they were the ones for which he wished to be remembered. Today they give us a glimpse of idealized Nordic beauty, of the role of physical fitness (either as pastime or fantasy) for gay men, and of the significance of gymnasiums, swimming pools and fitness clubs as venues for discreet or overt sexual fraternization.

The Finnish painter Magnus Enckell was born into a Swedish-speaking family in a provincial town of eastern Finland, the sixth child of a Lutheran minister. He studied in Helsinki, then at the Académie Julian in Paris, where he became the leader of a small group of expatriate Finnish artists who embraced Symbolism. While there, he saw Vaslav Nijinsky dance in L’Après-midi d’un faune – the inspiration, according to the art historian Juha-Heikki Tihinen, for several paintings of fauns. The Ballets Russes impresario Sergei Diaghilev even helped Enckell to arrange a display of Finnish art in the French capital. After returning to Helsinki from a stay in Italy, he helped found the Septem group and was a major figure in Finnish culture, even if he never fully subscribed to the nationalistic themes that dominated his generation as the country struggled for independence (realized only in 1917). Photographs show a handsome, dapper gentleman. He had a son, though he never married the mother.

Although Enckell is still little known outside his native country, his compatriots placed him in the pantheon of great national artists. Not until 1994 did a commentator refer in print to the artist’s homosexuality, which nevertheless seems to have been an open secret during his lifetime. A decade later, the biographer Harri Kalha published a volume that addressed the question of Enckell’s private life for the first time.

Coming from the far north of Europe, Enckell was one of those men with homosexual inclinations for whom the Mediterranean was both destination and inspiration. He lived in Italy from the mid-1890s until 1905, when he returned to Helsinki with a new artistic style and with richer colours that marked a change from his earlier sombre palette. He also came back with a man named Giovanni, who worked as his model, driver and manservant (photographs show a robust Italian posing nude in Enckell’s studio).

Enckell painted many variations on the theme of the male nude. A dark-haired youth emerges naked from his bedcovers in The Awakening (1893), Enckell’s most famous painting. Elsewhere a young blond sits meditatively on a rock by the water, radiating sunshine, while in another work a youth not yet tanned by the summer rests his head pensively in his hand as he gazes into the distance. In Wings (1923), two boys stand together, the one in front looking beatifically upwards, his arm silhouetted against a burst of cloud and sky, while his friend glances modestly downwards. In a nod to mythology, a slender youth balancing a lyre on his thigh, a cloth discreetly covering his private parts, perches on the edge of a pond on which six mysterious black swans swim. Another naked boy, his back and buttocks revealed as he wades in a pool, wrestles with a massive white swan. A mustachioed faun stares mischievously from one canvas. A handsome Narcissus bends across a boulder to stare at his reflection in the water. In one of the loveliest pictures, The Faun (1914), a beautiful boy whose carmine lips and cheeks match the tunic thrown across his loins reposes on the forest floor, his smooth marble-like flesh capturing the rays of morning sun as he raises his hand to his forehead as if roused from a long sleep.

Enckell’s pictorial world is an Arcadia of statuesque ephebes who disport themselves in glades and rivers, evoking sylvan innocence (though it conceals, or perhaps reveals, ardent desire), budding manhood and intimated passion. Some Finnish critics viewed his works with discomfort, criticizing those paintings suffused with a Mediterranean, mythological spirit as foreign and decadent. Homosexuals, on the other hand, no doubt found in him a kindred spirit. In the secret of his notebooks, Enckell confessed his kinship with antiquity. In a poem on ‘Antinous’ he declared, ‘I also am of your family / I know you well’, swearing a vow to honour the sacred memory of the beauty, love and sacrifice of Hadrian’s companion.

Enckell’s images of bathing boys recall Thomas Eakins’ The Swimming Hole and other softly erotic mises en scène of young men by the water, including those by Verner Thomé, a fellow Finn and member of the artistic group Septem. They bring to mind a culture of easy nudity at the seaside, and the magic of the brief Nordic summer. There is, to be sure, a streak of melancholy – one naked boy crouches on the ground holding a human skull – but also an effort to capture an ideal of beauty in a northern setting.

Homosexual acts remained criminal in law and unacceptable in Finnish society, but the sensitive and shy artist found ways to embody his desires in his pictures and, with Giovanni, to find personal happiness.

Donald Friend was a peripatetic artist and novelist whose paintings and drawings illustrate his sexual and romantic liaisons. Recorded in his voluminous diaries, these encounters took place all over the world, from Australia to Nigeria, from Britain to Italy, and from Sri Lanka to Bali.

Friend was born in Sydney, the son of a wealthy family of graziers, and spent his childhood either in their vast sheep station and or at their city apartment. His earliest meaningful sexual adventure was with a half-Thai man who worked on the family estate. ‘He was … my first friend,’ Friend remembered, ‘and I suppose, though my interest had lain in that direction since childhood (Christ knows what was the original cause) [it] had much to do with that interest in orientals and orientalism which spread to include the whole coloured races of the world and has always been the strongest factor and influence in everything I’ve done.’ When they were discovered in bed, Friend ran away to Cairns, in far north Queensland, where he took up with Malay, Melanesian and Aboriginal inhabitants of the then ramshackle pearl-lugging port. The tropical cosmopolitanism made a change from outback Australia and from Sydney, which in the inter-war years was still a staid British outpost. The luxuriance of the environment and the appeal of the men inspired a life-long journey.

In the early 1930s Friend moved back to Sydney and studied at art school. In 1936 he took the decision – as was de rigueur for Australian gentlemen and artists – to travel to London. While he was there, a Nigerian acquaintance and bed-partner, who also modelled for Friend’s first mature oil painting, suggested that he should go to Africa. So it was that Friend spent several happy years in the country of the Yoruba people, working in a vague capacity for the local ruler and continuing to draw, paint and write.

With the start of the Second World War, Friend returned to Australia and enlisted in the army. After a stint as an artillery gunner, early in 1945 he became an official army artist. He was sent to the island of Borneo, which provided further opportunities for art (he painted harrowing images of the ravages of warfare) and sexual adventure. The experience sharpened his critical view of colonialism and reinforced his yearning for overseas places. His travels continued after the war: back to Sydney, then on to the Torres Strait, an abandoned mining town in rural New South Wales, Italy in 1949, and once again to England.

In 1957 Friend halted for five years in Sri Lanka. Here he found the landscapes, and the type of young men, that he loved. His work from this period, which borrows some motifs from Ceylonese temple art, is especially accomplished. After a five-year stint in Australia once again, in 1967 the footloose Friend moved on to Bali, an island of legendary beauty that since the 1920s had attracted a coterie of homosexuals, such as the artist Walter Spies and the composer Colin McPhee. ‘The island itself for years had been a favourite part of my imagination’s geography,’ reminisced Friend, adding that ‘a Westerner could live like a king in Bali in 1967, and I did … My 25 houseboys liked working for me … They called me Tuan Rakasa, which means Lord Devil, but I was a benevolent devil.’ He had a final homecoming to Australia in 1980 and spent his last years in Sydney.

Critics acknowledged Friend as a fine artist – Robert Hughes judged him the best draughtsman among Australians – and his work found eager collectors and exhibitors. His constant theme, though by no means the sole one, was young men, especially the exotic youths he encountered while travelling. They appear in unadorned portraits, or are shown slumbering in island heat, playing indigenous musical instruments, or posed against landscapes of the Australian outback or Asian villages. Friend’s paintings are never pornographic, but his young men – who were generally his lovers, houseboys or neighbours – do carry a seductive charge. Friend was open about his homosexuality – hardly a welcome subject everywhere, particularly since homosexual acts were still illegal in Australia. Artistic talent, wealth, discretion and his frequent absences overseas kept him from trouble, however, even though the last perhaps made his work less appreciated during his lifetime than it might otherwise have been.

Friend was also a fine (and still undervalued) writer in a number of genres. His memoir Donald Friend in Bali (1972) offers a colourful account of life in the East Indies. His novels often include mordantly humorous stories about expatriates in remote corners of the world. Friend’s great skill at satire is especially evident in several illustrated albums, especially one boisterous volume entitled Sundry notes & papers: being the recently discovered notes and documents of the Natural & Instinctive Bestiality Research Expedition, collected and collated under the title Bumbooziana. It is a wild sexual romp – in this case cheerfully pornographic – in the form of an illustrated adventure tale. The exploits of a ‘Beast of Basra’ who displays formidable phallic prowess, a German scholar who specializes in toilet graffiti, a Polynesian prince with tattooed genitals who is all the rage in Mayfair, and a discourse on Little Red Riding Hood as a transvestite exhibitionist lesbian with a grandmother fetish are only a few of the book’s delights.

Since Friend’s death, a four-volume edition of his diaries and a one-volume abridgement have been published. They deserve a place among the classics of both Australian and gay literature. Friend was a deft literary craftsman, and his diaries chart the evolution of artistic milieux in Australia and Britain, and the colonial and post-colonial situations of the countries in which he lived, as well as the development of his own work. Not surprisingly, they also detail his sexual adventures. Friend treats these in a witty, reflective and self-critical fashion, showing the opportunities but also the hazards that awaited the European gay man abroad, in places where the homosexual living was easy, but where romantic entanglements could make for some hard choices. He writes, too, about his long-lasting sexual partnership, and then enduring friendship, with an Italian who shared his life in Ischia, London and Sydney.

‘Goodbye world of lovely colours and amicable nudes,’ was how Friend signed off his diaries. His life had been lived in the company of artists, writers, expatriates and friendly ‘natives’, full of globetrotting pleasures and serious dedication to art and literature.

Alair Gomes was a Brazilian photographer whose main subject – to judge from the 170,000 negatives he left behind – was the young men who went to the beach of Ipanema in Rio de Janeiro. Gomes shot them from the windows of his sixth-floor flat, or invited them into his apartment for sexual encounters and photographic sessions.

Gomes’ photographs constitute a remarkable compendium. He noted that pictures of male nudes usually fell into three categories – pornography, ‘artistic’ studies, or images in which potent masculinity is somehow subverted – but rightly felt that his own works did not fit into any of these genres. He drew inspiration from many and varied sources: classical culture (illustrations of statuary decorated the walls of his apartment); the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson, of whom he spoke admiringly; religious iconography, which informs his ‘triptychs’ and friezes of nudes; and film and music. Gomes’ masterwork is a series of 1,767 photographs of men entitled Symphony of Erotic Icons, arranged in distinct ‘movements’ of allegro, andantino, andante, adagio and finale. He insisted that his visitors might only see the pictures if they agreed to view the entire sequence in order, and that the images should not be otherwise displayed.

Gomes photographed the carnival in Rio, and shot urban scenes during his trips to the United States and Europe, but it is his images of men that command most attention. The long hairstyles worn by his subjects in the 1960s, and the bell-bottomed trousers that appear occasionally in the American photos, are the only hints of a specific time. As for place, the men inhabit a setting that could be Carmel (which he did photograph), Sitges or Bondi as easily as Rio. Shadowed on the pavement, they cross the street, sometimes carrying surfboards; they exercise on gym equipment on the beach or lounge in the sand, wearing only small swimming costumes. The indoor portraits show them lying naked on a bed, the camera focused on their genitals, buttocks or chests. Gomes’ subjects are uniformly masculine and beautiful. His pictures highlight their virile attributes of muscles and body hair: indeed, few other photographers take such an interest in the hirsute landscapes of chests, buttocks and legs. Somewhat oddly in a country that has so many people of mixed racial ancestry, Gomes’ men almost always have stereotypically European features and skin colour.

Gomes admitted that he was an obsessive photographer, and remarked of his men that ‘when they see me photograph them obsessively, they understand this as a glorification of their beauty’. The ‘erotic homage’ (his words) that the corpus of his photographs represents has something of the ethnographic or even zoological: countless specimens of spectacular bodies, the images emphasizing the animality of the taut, lithe, feline young men; bodies caught in innocent play, but also sometimes curled into vulnerable curves. There is, too, a dialogue between exhibitionist and voyeur. In one picture a young man holds a mirror above his naked, hairy body, in which is reflected the bespectacled, weedy photographer with his camera, crouched between the boy’s legs, arms encircling the youth’s thighs.

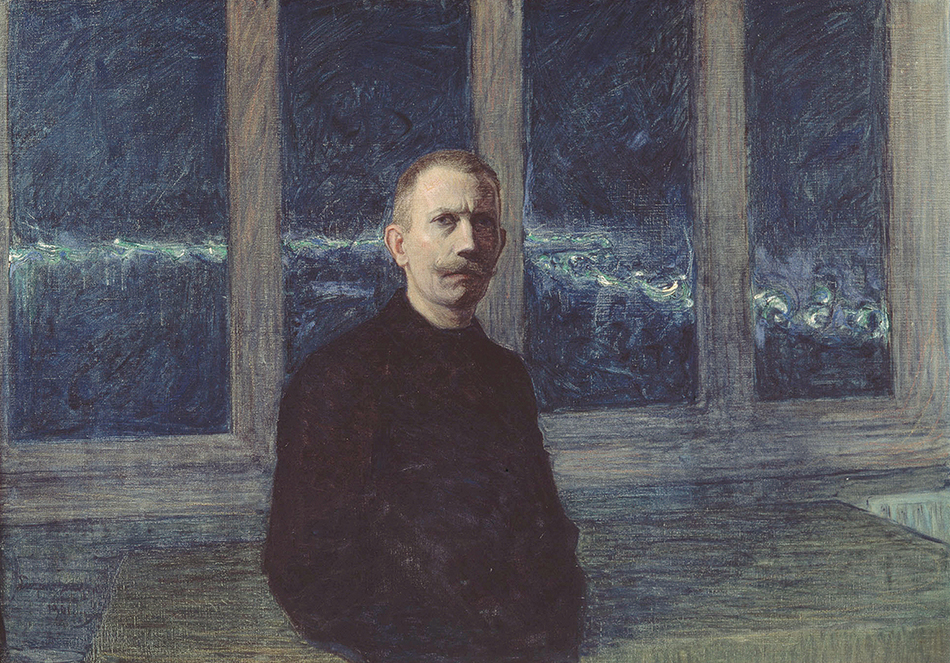

Alair Gomes, Beach, c. 1970–80 (Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris)

There is a complicity between subject and object, but a complicity within limits. One wonders what emoluments Gomes might have provided to his young men. What did they make of the ageing photographer, who must have been a familiar figure in Ipanema, wandering the beach or taking a succession of men into his flat? What were the circumstances under which one man Gomes had invited home murdered him, at the age of 71?

Gomes came from a middle-class background and had graduated in civil engineering. He worked for the Brazilian railways for a while, but also established a literary review. After a religious crisis in his twenties, he returned to university to study science and philosophy, and won a fellowship for travel in the United States, where he spent a year at Yale University. Having returned to Brazil, from 1962 he taught philosophy of science at the Federal University of Rio and contemporary art at a school of visual arts, regularly participating in international academic conferences and publishing papers in art criticism and the philosophy of science. For a decade from the age of 32, he kept a detailed ‘erotic diary’ that recorded his sexual liaisons, and painted and drew nudes. Only in his forties did Gomes begin taking the photographs that would become his passion.

By the last decades of the 20th century, overtly homoerotic art was common in the Western world. What was surprising was to see this art coming from India, especially when it portrayed mature men rather than the sleek, buffed boys omnipresent in Europe and America. Such themes, nonetheless, formed the dominant subject of the Indian painter Bhupen Khakhar.

Born in 1934, at a time when India was still under the rule of the British Raj, Khakhar came from a middle-class Gujarati-speaking background – his father was a successful cloth merchant and his mother the daughter of a schoolteacher – and spent his early life in Bombay. He took degrees in economics and finance at the University of Bombay. To the distress of his family, Khakhar then moved to Baroda, the centre of a nascent artistic movement and a fine arts university, where he took a diploma in art criticism. He would nevertheless spend his professional life as a chartered accountant, painting oils or watercolours before or after his day at the office. With little formal training in art, he became famous enough to enjoy one-man exhibitions at the Tate Gallery in London and the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Khakhar’s artistic influences ranged from Jain temple maps, Mughal miniatures and the popular kitsch oleographs and posters sold in bazaars to the paintings of le douanier Rousseau and Fernand Léger; they also encompassed 14th-century Italian artists such as Ambrogio Lorenzetti, whose frescos he discovered on a trip to Europe in the 1970s. Khakhar’s own work, which is often described as naïve, shows his interest in narration and his choice of figurative art over abstraction. Having first experimented with collages, he moved on to bright, geometric renditions of Indian daily life, depicting such subjects as a barber, a watchmaker, a teashop and his parents.

The artist knew early on that he was homosexual, though he was troubled by his desires. ‘I was very much ashamed of my sexuality. I never wanted it to be known I was gay,’ he remembered. Despite having had a number of liaisons in early adulthood, only his experience of the relative tolerance of homosexuality in England in 1979, and the death of his mother the following year, gave Khakhar the confidence to express his sexuality more openly. A 1981 painting, You Can’t Please All – which features a naked man on a balcony watching life below – represents a symbolic coming out: ‘I am also here taking off my clothes before the world.’ Khakhar’s coming out in life and art constituted a courageous gesture: under the old colonial-era law code, homosexual relations remained illegal in India until after his death, and opposition to homosexual expression is still widespread.

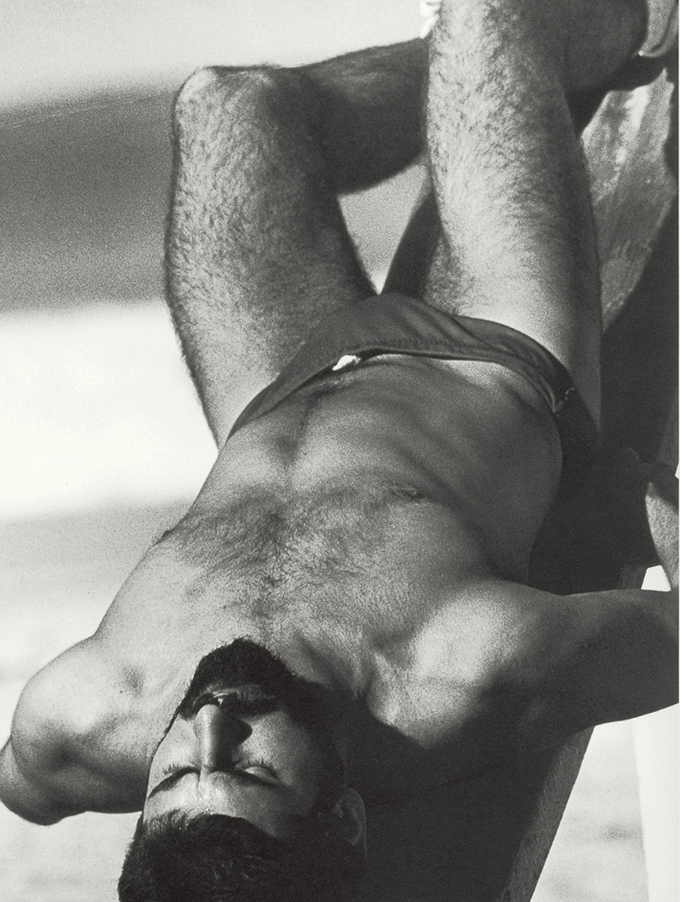

Bhupen Khakhar, 2002 (Courtesy Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai)

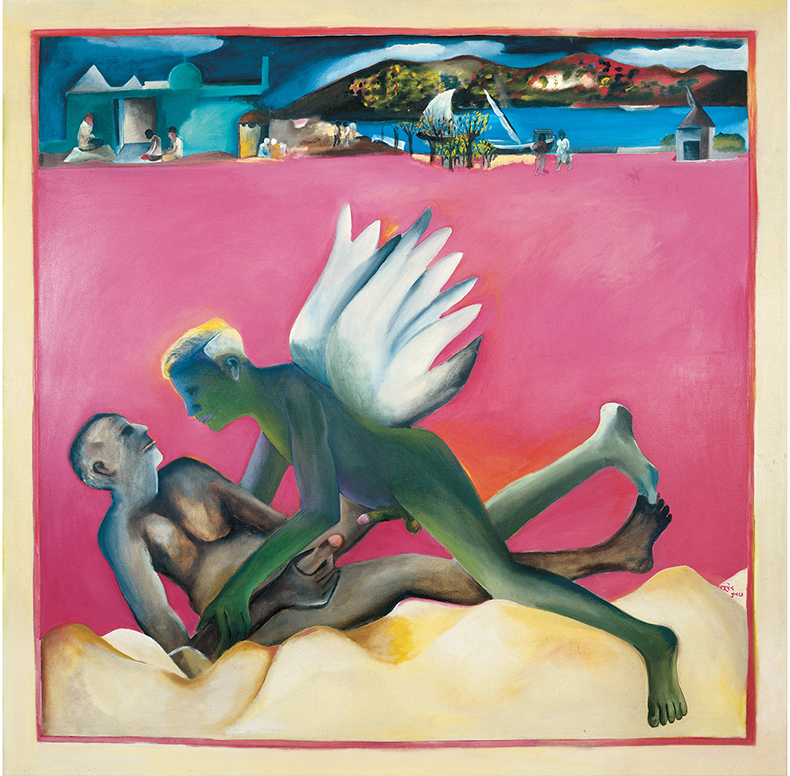

Bhupen Khakhar, Yayati, 1987 (Private collection/Courtesy Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai)

Glimmers of homosexuality appear in earlier works, but it was at the beginning of the 1980s that Khakhar began openly to portray same-sex sexual desire. Two Men in Benares (1982) features a dark-headed younger man and his white-haired partner, possibly the artist, standing naked and embracing; around them, in an arrangement Khakhar often used, small auxiliary scenes depict landscapes, a man receiving a massage and various enigmatic figures. My Dear Friend (1983) pictures two men conversing in bed while two others voyeuristically gaze at them, it seems, through the roof. In a Boat (1986) shows a vessel floating on a dark body of water, a rocky landscape in the distance. What appears to be an orgy is about to take place on board: two naked men begin an embrace, two others almost divested of their clothing look on expectantly, and yet another man offers a glass to a muscular partner, who flirtatiously sticks out his tongue. Perhaps Khakhar’s most remarkable homoerotic work is Yayati (1987), named after a legendary king. Arranged across the top of the canvas are Khakhar’s characteristic vignettes of small landscapes and a domestic scene, but the painting is dominated by two greenish-grey men with erect penises set against a lurid pink-and-white background. Over one recumbent figure hovers a winged angel; the two figures’ arms and feet touch, evoking a visitation of desire and its satisfaction, or perhaps a dream of fulfilment.

Khakhar’s art communicates a kind of magical realism, tinged with considerable humour. One of his best-known works is An Old Man from Vasad Who Had Five Penises Suffered from Runny Nose (1995). There is tender lyricism as well, as illustrated by the two men in How Many Hands Do I Need to Declare My Love to You? (1995). Their multiple arms, string of beads and garland transform the couple into soaring Hindu gods.

Despite his concerns, the homoerotic content of Khakhar’s paintings did not compromise his reputation – in fact, the ageing artist earned honours at home and overseas. Producing portraits of such figures as Salman Rushdie, he became one of India’s best-known artists. The straightforwardness with which his works present sexual themes continues to surprise, but the masted ships, domed shrines, and bakers and tailors of the marketplace all provide a recognizably Indian backdrop, distinguishing his paintings from the vernacular homoerotic art of the West. By his own admission, he focused on tenderness and warmth, on ordinary, nondescript men, and on the quiet enactment of sexual desires. (Western-style gyms, gay bars and placard-wielding activism were in any case unknown in Khakhar’s India.)

Although Khakhar never abandoned his observation of other aspects of daily life, the sexual panoramas gained him new fame in gay circles. These homoerotic works by an Indian painter are not some Orientalist fantasy dreamed up by a European traveller, but the expression of same-sex eroticism embedded within the indigenous culture of his homeland. In the gallery of Khakhar’s paintings, a man savouring jalebi sweets, a sage celebrating a religious festival, a group gathered for a tea party on a terrace and two men having sex blend easily into the infinitely varied canvas of Indian society.