There is a long tradition of homoeroticism in classical Arabic and Persian writing. Indeed, one type of poetry, which exalts the beauty of youths, is sometimes interpreted as a metaphor for the mystical love that exists between man and God. One of the earliest and most famous practitioners of this genre, and, according to some, the greatest of all Muslim poets, was Abu Nuwas.

Abu Nuwas – actually a nickname that means something like ‘the man with flowing locks’ – was born in the mid-8th century, most likely in Ahwaz, which is situated in modern-day Iran. His mother was a weaver, and his father, whom he never knew, was a soldier. Mother and child moved to Basra, where the handsome young Abu Nuwas attended Koranic school and, under the influence of his uncle, began to write poetry. He then moved to Baghdad, where Harun al-Rashid (immortalized in One Thousand and One Nights) held court. The pious caliph did not take to the poet, however, and twice had him imprisoned for his dissolute life, satirical works and involvement in court politics. Abu Nuwas’s alliance with a disgraced vizier’s family also forced him briefly into exile in Egypt, during which time his only son died.

Apart from that one unwelcome absence, Abu Nuwas spent the remainder of his life in Baghdad, one of the great centres of Arabic civilization. He got on well with Harun’s successor and son, al-Amin, a former student who (according to the Orientalist Vincent-Mansour Monteil) shared Abu Nuwas’s taste for youths, wine and hunting. Four years of libertine life in the pleasure quarters of Baghdad – where Christians, Zoroastrians and Jews sold wine, in principle forbidden to Muslims – followed al-Amin’s accession to the caliphate and Abu Nuwas’s return from exile. Abu Nuwas gained a reputation as a fine poet, a drinker and a lover of ephebes (notwithstanding occasional dalliances with courtesans), though he also reputedly completed the pilgrimage to Mecca. The last two years of Abu Nuwas’s life, after the assassination of his protector, were more difficult. Sources diverge on whether he died at home, in prison or in the house of a cabaret-owner.

A man and a youth drink wine by a stream – the type of scene celebrated in Abu Nuwas’s poetry. Glazed dish, Iran, c. 1200 (David Collection, Copenhagen)

Abu Nuwas is best known for his erotic and bacchic poetry, in which he expresses his enjoyment of wine and the delights of the youths he called ‘gazelles’ (the word is also translated as ‘fawns’), many of whom were servants or slaves. Abu Nuwas wrote lyrically about long evenings in the tavern, far from the rigorous demands of mosque worship. One poem enjoins a waiter to refill the cup of a cute lad so that he will loosen his trousers and allow his drinking companion to take him into his arms. In another Abu Nuwas confesses that he has given up girls and war for young men and aged wine. The poet flirts, is infatuated, seduces and falls in love; his verses linger on the beauty of a pale shoulder, a pretty face, well-shaped legs or a gentle voice. Away from the cabaret, the school also provides fetching youths; and in the bathhouse, he says, that which trousers hide is deliciously revealed. His overtures meet with success. Even when passion is not reciprocated, in the next cabaret or around the corner there is always another beckoning youth – a new conquest for him to pursue.

Abu Nuwas had many successors, and works touching on affections between men, extending from pure intimate friendships to the varieties of sexual intercourse, became an important part of medieval Arabic and Persian literature. Ahmad al-Tifashi, born towards the end of the 12th century in present-day Tunisia, devoted five out of twelve chapters of one of his treatises – available in English as The Delight of Hearts – to a miscellany on homosexuality, including poems, jokes and gossipy anecdotes. His descriptions of same-sex encounters run the gamut of experiences, ages and emotions. They include the attraction of adult men for each other (‘beardophiles’), as well as the lust of older men for youths. Taken at face value, they portray an unbridled and unabashed homosexual culture.

In his treatise al-Tifashi reproduces more than a dozen poems by Abu Nuwas and repeats several anecdotes about him. In one story, Abu Nuwas passes through the city of Homs, where a resident, hoping to converse with the famous poet, takes his son to find him at his inn. They ask the first man they see there to direct them to Abu Nuwas, and the stranger promises the information in return for a kiss from the handsome boy (the man, of course, turns out to be Abu Nuwas himself). In another anecdote, Abu Nuwas says that his great dream would be to find a young man to bed without committing a sin. Another partner, however, counsels him that he will receive no favours in heaven if he does not favour those whom he loves on earth. Al-Tifashi’s stories – which may or may not have a basis in fact – also record that Abu Nuwas had a sexual relationship with his teacher, and that he composed his first poem, on the theme of a handsome boy, in a verse-making contest with a Bedouin who had recited an ode to camels.

The 13th-century Anatolian Rumi and the 14th-century Persian Hafiz count among later Muslim versifiers who extolled the pleasures of wine and youths, although, as with Abu Nuwas, some commentators insist that the works about sexual intercourse should be seen as symbolizing ecstatic union between the human and the divine. Their poems nevertheless inspired many Western homosexuals, including those who travelled to Arabic countries in search of the joys they promised. A procession of visiting writers – from Gide and Genet to Paul Bowles and Joe Orton – popularized North Africa as a destination where seductive young men, for love or money, eagerly offered companionship and sex in the seductive setting of the kasbah, amid a haze of hashish and the eroticism of the exotic.

The law codes of almost all states where Islam is the major religion now deem homosexual acts to be criminal, punishable in some countries by long terms of imprisonment, public flogging and even execution. Homosexuality nevertheless exists throughout the Arabic and Islamic world (as it does almost everywhere), even if relatively few who engage in same-sex relations consider themselves homosexual in a Western sense. An ostensible divide between the active and passive role in sexual relations preserves honour, and most men, whatever their erotic and romantic inclinations, marry and beget children. A new tradition of homosexual representation is now emerging gradually in Arabic countries and within the Muslim diaspora – for instance, in the novels of the Moroccan who writes under the name of Rachid O., and in the 2009 Tunisian film Le Fil (‘The String’). The works of Abu Nuwas remain testimony to an earlier, celebratory tradition of Middle Eastern eroticism.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Mediterranean port of Alexandria hosted a variegated population of Egyptian Arabs, Jews, British (virtual rulers of Egypt, even if the country was not officially a British colony), Frenchmen, and a large community of Greeks. Sited at the crossroads of three continents, it was a city of elegant cafés and busy markets (Lawrence Durrell’s The Alexandria Quartet captures its atmosphere well). Alexandria blended its Hellenistic heritage with modern commerce and the dynamics of imperialism. The stock exchange handled vast supplies of Egyptian cotton, which were dispatched to European factories from its crowded port. Luxury and squalor, adventure and mystery mixed in a city where Orthodox cathedrals and mosques stood near each other on French-style boulevards.

Alexandria was Constantine Cavafy’s city: it appeared, in its ancient and contemporary incarnations, in his poetry, and was also the theatre of his erotic pursuits. Cavafy was born in Alexandria to a family of Greeks who had moved there from Constantinople. His mother was the daughter of a diamond merchant, while his father worked as the head of an import–export business established in England with one of his brothers in the 1840s. A few years after Cavafy’s birth, the family returned to England, where the boy spent his adolescence, becoming fluent in English and conversant in English literature. After his father’s death, the company began to struggle and was finally liquidated in 1879. The family returned to Alexandria, then moved to Constantinople, where Cavafy spent three years in the 1880s. Returning permanently to Alexandria in 1885, he worked briefly on a newspaper, then as an assistant to a stockbroker brother. At the age of 29, Cavafy secured employment with the Irrigation Service of the Ministry of Public Works, a job he kept, rising to the position of assistant director, for thirty years.

In the meantime, Cavafy had begun writing poetry. He was a meticulous stylist; using language that blended literary and demotic Greek, he worked and reworked his poems, rarely allowing publication, but gradually gaining a high reputation among those who knew his writings. They included E. M. Forster, whom he met during the First World War when Forster served as a volunteer in the British medical service in Alexandria. The two became friends: Forster wrote about Cavafy in his books on Alexandria and helped arrange publication of some of his poems in England.

Cavafy’s two themes, sometimes intertwined, were history and eroticism. In the first lines of a poem not published until decades after Cavafy’s death in 1933, two naked swimmers emerge from the water on a perfect Mediterranean summer’s day; the lovely scene then merges into a disquisition on a 14th-century Neoplatonist defender of Hellenic education. The period of history that most interested Cavafy was the transition between paganism and Christianity, between the Hellenistic and Byzantine worlds – life as it was lived on the eastern margins of the old Greek civilization. His eroticism was homosexual.

Biographers know relatively little about Cavafy’s own romantic and sexual life. It seems that he had a couple of meaningful short-lived affairs, as well as casual encounters. His sexual initiation may have come when he was living in Constantinople, but it is clear that he wrestled with his sexual orientation, and only began showing, and occasionally publishing, his erotic poems when he was in his forties.

Most of Cavafy’s poems about love and sex are memories of encounters, whose details have sometimes faded with the passage of years. Sitting alone, he recalls chance meetings, hears the half-forgotten voices of partners, dreams of the caresses of his lovers. As ‘the body’s memory awakens’, he remembers, with renewed yearning or a sensation of serene comfort, the beautiful young men with whom he had sex.

Cavafy’s lovers, and the lovers of the historical characters who haunt his poems, are handsome, well-built men in their twenties, with grey or sapphire eyes, jet hair and pale foreheads – men often of modest condition whose brazen beauty is revealed only when they throw off tattered clothing. A man seemingly fashioned by Eros himself beckons from a café. Meetings take place in the twilight of busy streets or late at night in tavernas. Two men exchange looks outside a tobacco shop and begin their lovemaking in a carriage. Another couple connects on a jetty. Just at closing time, a passer-by fabricates a wish to buy handkerchiefs, to make contact with a shop assistant whom he spies through the lighted window. In the small hours of the morning, a wine-shop forms the backdrop for another encounter: two young men rushing to satisfy their desires behind a screen while the waiter dozes. Sometimes a pair takes refuge in a sordid little hotel room. The encounters are fortuitous, but they are also facilitated by money given to an impoverished youth – perhaps the son of a sailor, or a blacksmith’s apprentice – in the city’s bars and restaurants.

Behind debauchery, there lies innocence. A village youth dreams of the pleasures of the metropolis; a city boy waits anxiously for his beloved, late for a rendezvous; a man tries to resolve unrequited passion, or relives the affection of a lover conjured up by a portrait; a shocked newspaper reader learns that an old flame has been murdered on the waterfront.

In evocative language and crystalline narratives, the poet resurrects these men from his memory; they appear as the ‘shades of love’ before his lamplight. The pleasures may have been illicit, desire at times shadowed with shame, or unions may have been sundered after a few moments. For Cavafy, the yearnings are innate, not degenerate, and ‘needless the repentance’. Those who dare to unbridle their impulses – and Cavafy bemoans the ones, possibly including himself, who do not dare enough and who must live with the regret of being so close so many times – will experience ecstasies that, like youth and place, can only be transitory, but that can also become the stuff of both poetry and memory.

Cavafy’s poems have great power and depth. They are well known in translation – ‘Waiting for the Barbarians’ (1898) and ‘Ithaka’ (1910), for instance, stand as two of the greatest modern poems in any literature – and his erotic verses have been illustrated by David Hockney, Alekos Fassianos and other artists. A rather mannered movie, made in 1996, openly considered his homosexuality, a subject that many early commentators thought taboo, since Cavafy is viewed as the most important modern Greek poet. Today’s visitors to dating websites and frenetic clubs might find an ageing recluse’s recollections of furtive encounters in the backstreets of a Levantine city somewhat dated. Yet the essence of desire and its satisfaction, placed in the seductive setting of the ancient and modern polis, has no finer or more intoxicating distillation than the verses of the Alexandrian poet.

To many in Britain and beyond, Lawrence of Arabia was a great hero of the early 20th century. He seemed the very model of an Edwardian scholar–gentleman, with his cosmopolitan interest in the romantic past and exotic overseas places. He was born in Wales, to a baronet father and a mother who had been a governess; the couple lived as husband and wife, although they never married. Lawrence was educated at Jesus College, Oxford; like many undergraduates he travelled to the Continent during the long vacation, but also ventured farther afield, visiting Crusader castles in Lebanon and Syria, then part of the Ottoman Empire. Reading widely during his university years and afterwards, he mastered a number of languages, and would later publish a translation of Homer’s Odyssey. After graduation, Lawrence spent four years as a field archaeologist, working in Turkey, Syria, Egypt and Palestine, particularly on Assyrian and Hittite sites at Carchemish.

However, it was for his military and literary activities rather than his archaeological work that Lawrence became famous. In 1914 he was commissioned in the British armed forces and posted to an office job in Cairo, but soon became involved in the Arab Revolt. Arab nationalists, supported by the British government for strategic reasons during the First World War, began to mount a campaign against Ottoman domination. Lawrence allied himself with Emir Faisal and took part in Arab operations that conquered Aqaba and Jordan. His exploits were widely recorded, and Lawrence returned home from the war a lieutenant colonel and a celebrity.

Lawrence became a government adviser, first at the Foreign Office, and then at the Colonial Office. In 1917 he took up a fellowship at All Soul’s College, Oxford. This gave him the opportunity to write his memoirs of the Arab campaign: a huge, sprawling tome called Seven Pillars of Wisdom, which was published in 1926 and abridged one year later as Revolt in the Desert. Despite his efforts as a delegate at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Lawrence’s hopes for an independent Arab state had been dashed. The British and French divided up the old Ottoman Empire into protectorates that they ruled, effectively as colonies, under League of Nations mandates. Not until after the Second World War would the Arab lands become independent states, except for Palestine, partitioned to create the Jewish state of Israel.

After the Great War, Lawrence continued in military life, amid his other activities. In 1922 he enlisted in the Royal Air Force under a pseudonym, then was forced to transfer to the Royal Tank Corps when his identity became known. After successful petitioning he was allowed back, and served in India for a couple of years. He left the military in 1935, shortly before his death in a motorcycle accident.

Behind Lawrence’s heroic, if enigmatic, public persona lurked several homosexual secrets – or rather half-secrets, since he intimated his sexual proclivities and experiences in his writings. The first pages of Seven Pillars of Wisdom reveal Lawrence’s erotic interest in young Arabs and the sexual tensions of his desert life with them. He explicitly mentions their sexual play and his empathy with their frolicking. In 1911 he met Selim Ahmed, a 14-year-old known as Dahoum (‘dark’), well built and handsome. Lawrence took to the youth and sculpted his likeness (nude) in limestone for the roof of his house. His diaries began to include discreet references to the young man as their relationship grew stronger. Lawrence finally took Dahoum on a visit to England, where he introduced him (and another Arab boy who had come along) to his mother and brother; one of Lawrence’s friends was so impressed with Dahoum’s beauty that he commissioned a portrait. Dahoum died, probably from typhus, during the war. Lawrence dedicated Seven Pillars of Wisdom ‘To S.A.’, and told the poet Robert Graves that Dahoum was the only person he would ever love. The book contains a poem that links his love with his struggle for Arab freedom: ‘I loved you, so I drew these tides of men into my hands / and wrote my will across the sky in stars / To earn you Freedom, the seven-pillared worthy house, / that your eyes might be shining for me / When we came.’

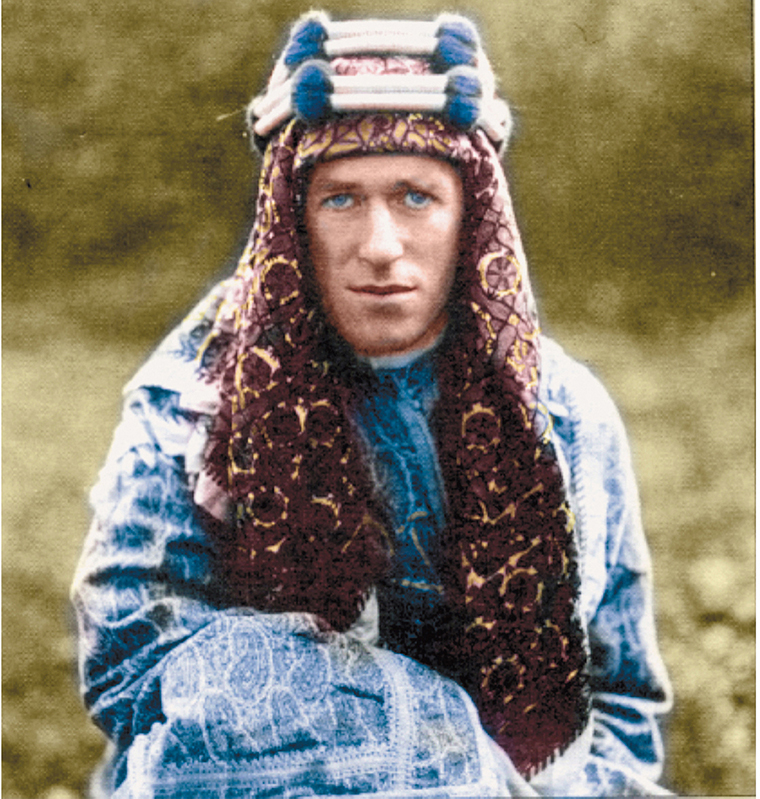

T. E. Lawrence in Arab dress, 1927 (Private collection)

Salim Ahmed (‘Dahoum’), c. 1913 (Photo T. E. Lawrence)

Another ‘secret’ revealed in Seven Pillars was the fact that Lawrence had been raped during the war. The details remain unclear, and Lawrence’s account leaves questions unanswered. Disguised as an Arab peasant, Lawrence had been reconnoitring the railway crossroads at the Syrian city of Dara’a for a possible attack when he was captured by Turks. The bey had Lawrence’s clothes stripped off and tried to fondle him; Lawrence kicked back. Lawrence was then slapped, cut with a knife, beaten with a whip, and repeatedly raped. (He later confessed in his recollections that he had experienced some sort of sexual pleasure during the incident.) The Turks bandaged his wounds, and Lawrence managed to escape. Lawrence’s most recent biographer, Michael Asher, comments that ‘there are no witnesses, no relevant diary entries, and no corroborating accounts’ of the incident, and that Lawrence was not reported missing to authorities over the two days that he was absent. Details vary in the different versions of the event that Lawrence recorded, and Asher casts some doubt on the veracity of his memory. Whether every point is true to life, however, it is certain that the experience and recollection of whatever occurred at Dara’a had a lasting impact on Lawrence. Back in London after the war, in 1922, Lawrence met a rough Scotsman named John Bruce, with whom he served in the military. Swearing him to secrecy, Lawrence hired Bruce to whip him, inventing a complex and far-fetched tale about his being obliged to receive corporal punishment as part of a promise to a vague relative, the ‘Old Master’, to whom he owed a financial and moral debt. In the carefully crafted scenario he invented for the first beating, Lawrence showed Bruce a letter purporting to come from the ‘Old Master’, specifying twelve strokes to his buttocks. Bruce, and perhaps other men, continued to flagellate Lawrence regularly until his death.

An explanation of Lawrence’s masochism, and any relation it may bear to the incident in Dara’a, is best left to psychologists, but it is worth remembering that Lawrence’s experience in the Levant was much coloured by his romantic and sexual sensations: an erotic charge felt among Middle Eastern youth; affection for Dahoum (which may or may not have extended to a sexual relationship); and the rape (no matter the exact details). The latter was a rare and traumatic experience. As for the sexual thrill and the romantic obsession, Lawrence, like many other homosexual men – Gide and Forster among them – found in the Arabic world the seductiveness of attractive men and the pleasures of erotic friendship.

Men are omnipresent in Yannis Tsarouchis’ art. Late in life he illustrated a collection of poems by Constantine Cavafy – a fellow Greek with whom he clearly felt both a cultural and a sexual affiliation – with simple line drawings of muscular youths and winged ephebes. Many of the men who appear in other works are soldiers or sailors. A young conscript prepares his belongings for his departure from home, a sailor sits quietly at a café table, reading and smoking; others pose in the sun, fit and statuesque, the glaring white of their uniforms contrasting with their black hair and swarthy skin. Soldiers in khaki dance the zeibekiko, their hard bodies animated by the gentle movements of arms and legs.

The erotic suggestions – Tsarouchis portrays Eros as a virile young man, not as a cheeky cherub – burst with barely contained desire, and sometimes hint at its satisfaction. One soldier divests himself of his clothes, while another sits on a rock and washes himself. In a painting of 1957, The Forgotten God, three sailors inhabit the cool Neoclassical décor that Tsarouchis favoured, their gazes a triangle of masculine intimacy. A man sits at a table, contemplating his two companions, one of whom, painted from behind, stands naked except for his leather military belt, shoulder strap, shoes and spats, facing another nude comrade. The extraordinary Seated Sailor and Reclining Nude (1948) depicts a seaman, smart in his white and blue uniform, seated on the bed of a naked, hairy-chested companion, who reclines on rumpled bedclothes. The painting was taken down from an exhibition after police declared it an insult to the Greek navy and threatened to ransack the art show. (Perhaps as a commentary, decades later Tsarouchis painted a work called Military Policeman Arresting the Spirit, in which the spirit was represented by his signature motif of a nude winged youth.)

Besides his homoerotic subjects, Tsarouchis also painted landscapes, still lifes, pictures of women (almost always in traditional folk costume, though his men wear uniforms or are undressed), and allegories of the seasons. While a catalogue of 1975 points out (in italic for emphasis) that his ‘real theme … is the masculine humanity of petty-bourgeois and semi-proletarian town-dwellers’, much later scholarship avoids the subject of homosexuality in his life and his art, and an autographical novel that he completed remains unpublished. The commentary to a collection of his prints and lithographs, issued just after the artist’s death, speaks of ‘love as lust and memory, an intention or promise, as desire and deferment’, and declares that ‘the love which Tsarouchis’s figures exude is a pagan, idolatrous and platonically idealistic love’, typified in his ‘renaissance-type guilt-free restoration of beauty’. The author declines to say that this is homosexual lust and love. Not until 2010, in a catalogue published by the Benaki Museum in Athens, did the art historical literature pay due attention to Tsarouchis’ homosexuality. Here, at last, was a frank discussion of how the artist accepted his orientation, despite the disapproval of his family and of Greek society, and his own estimation that he was a pioneer in overtly homoerotic art.

Tsarouchis was born in 1910 in the port city of Piraeus and educated at the School of Fine Arts in Athens. He began painting at an early age, but earned his living mainly as a designer of theatre sets and costumes, working for La Scala, Covent Garden, and the Théâtre National Populaire in Paris, and with Franco Zeffirelli. In 1935 Tsarouchis went to Paris for the first time, where his ideas, already influenced by the Fayum portraits, Byzantine icons, Coptic weaving and Greek popular art, were further fertilized by exposure to the Old Masters and Matisse. His own style continued to reject the trends of the avant-garde in favour of naturalism. He held his first solo exhibition in 1938, after his return to Athens.

During the Second World War, Tsarouchis served in the Greek army on the Albanian front. Afterwards, he settled into a happy and successful period, painting, working in the theatre and increasingly gaining an international reputation. In 1967 he went into self-imposed exile during the military dictatorship in Greece, living near Paris. In 1980 he returned to Athens, where he died nine years later.

Tsarouchis’ men resonantly strike the gay spirit. Works of the 1970s feature androgynous, long-haired hippies, reflecting the fashion of the times. But most of his images are of masculine soldiers and sailors, objects of fascination and fantasy. Tsarouchis’ variation on the theme of machismo is to invoke a gentle, joyful and sometimes melancholy innocence that kindles thoughts of youthful idols rather than the aggression of real military life. Groups of sailors disrobe on the beach or commune in the café, posing seductively for each other and for the viewer. The peasants, fishermen and artisans-turned-sailors seem ready to offer, or bargain, their bodies for pleasure, unconcerned about troublesome questions of sexual identity or social conventions.

The stylized, minimal backgrounds of Tsarouchis’ erotic paintings evoke sun and sea, strong coffee and dark red wine. His art is deeply Mediterranean, his pictures occasionally evoking classical ancestors: a painting of the eternally youthful and forever sleeping beauty of Endymion; a shapely young man beside a bust of Hermes; a drawing of Orestes and Pylades as two nudes in a modern bedchamber. The title of one work is descriptive of the connection between ancient and modern: Youth Wearing Pyjamas Posing as a Statue from Olympia. Hunky men sporting wings (occasionally highly coloured like those of butterflies) seem to be visitors from a world of antique gods or erotic Christian angels. ‘Love, Love, Love’ reads the inscription on one such work, an acclamation of the god’s vocation and the artist’s longing.

Tsarouchis said that he was attracted to both the Occident and the Orient, the West of modernity and the Levantine East, where, he opined, vestiges of a more happily primitive society survived. Like Wilhelm von Gloeden and Pier Paolo Pasolini, he found in the ragazzi di vita the inheritors of the ancient world and the preservers of pagan morals. Perhaps the universality of Tsarouchis’ vision of homosexual desire, combined with the particularly evocative backdrop of the Mediterranean, explains the power of his works.

Naming gay men in the modern Arab world is difficult. Few men speak openly about their same-sex attractions; laws and the conventions of society condemn homosexuality; sex is not a matter for public show; and gay men run real risks if they pursue their desires in Cairo, Tehran or the other cities of the Middle East. Ali al-Jabri, partly protected by his privileged background, was something of an exception. His life and death – he was killed in his apartment in Amman by his Egyptian lover in 2002 – show the possibilities for homosexual expression in this world, but warn that limits can sometimes be trespassed with fatal consequences.

Al-Jabri boasted an extraordinary lineage, but the family’s past and his discomfort with their expectations weighed heavily on him. He was born in 1942 in Jerusalem. His father had graduated from a university in Istanbul, and his mother (a cousin of her husband) had studied at the elite Vassar College in the United States. They both came from a grand, landed and wealthy family from Aleppo in Syria. Al-Jabri’s maternal grandfather was first secretary to the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet V, then became chamberlain to the future Saudi King Feisal during the Arab Revolt (1916–18); much later, in 1958, he switched his support from Arab monarchs to the socialist Gamel Abdel Nasser and won appointment as prime minister of the United Arab Republic, the short-lived union of Egypt and Syria. A great uncle of al-Jabri initially contested French expansionism in Syria after the First World War, then became prime minister of the French protectorate. Al-Jabri’s uncle served as prime minister of Jordan (he was murdered after his crackdown on Palestinians in 1970), and his father held several ministerial portfolios in Damascus, though he spent much of his professional life working as a contractor in Kuwait.

Al-Jabri’s route through life was no less extraordinary than his pedigree, taking him across the Arabic world and far beyond. He was sent to Victoria College in Alexandria (and briefly to boarding school in Switzerland), but after the coup d’état against King Farouk in 1952 he was dispatched to England, where he finished his secondary education at Rugby. He continued his studies at Stanford University in the United States, but in the heady atmosphere of sex and drugs of the mid-1960s the tall, handsome, elegantly dressed Levantine dropped out, prompting his father to fly to California to bring him under control. Having returned to England, he finished a degree at the University of Bristol, then spent a period in London in the 1970s, working as a low-level bureaucrat at the Jordanian embassy, painting and living a bohemian existence. He spent the last decades of his life mostly in Cairo, with occasional periods in Amman, and largely lived off handouts from his aunt, who was the widow of King Hussein’s prime minister. Sporadic artistic commissions, including ones from Queen Noor of Jordan, rounded out the budget.

Al-Jabri’s homosexuality, according to his friend and biographer Amal Ghandour, was an open secret. His liaisons ranged from unrequited affairs to long-term intimacies and casual encounters. For quick rendezvous, al-Jabri ventured into Cairo’s huge cemetery-cum-shantytown. His diary records fragmentary impressions: ‘Hustle, Hustle, Hustle … one o’clock … A taxi to the City of The Dead in search of pals and dope but a wrong stairway got me straying into a gang of miscreants … followed me threaten menace … wrench my wrist, grab watch and demand bread … Thank God I was not too far deep and got away … smack into two soldiers hungrily waiting for it … on a darkened plain by a tin statue of defunct poet staring into oblivion … more money changed hands, though this time more equally…’. Such misadventures did not dissuade al-Jabri from other lustful peregrinations. Again he wrote in his diary that ‘they want money, I want love! – or is it me who hunts for the dark gutter’s silver lining finding only the fascination of the unobtainable? Tastes, the bitter keenness, solitary marathons in the midnight streets … hideout haunts, the City of the Dead, among tombs, domes, sand piles, crumbling mortar … the sweet music of Muslim mortality made miraculously into living flesh by the music of the living among the early shadows of morn’.

Many of al-Jabri’s paintings picture the distinctive architecture of Middle Eastern cities, focus on the austere details of stone buildings or are quiet still lifes, while a series on The Arab Revolt caricatures modern Arabic society and politics, of which he was highly critical. There are portraits of his grandfather and of the singer Um Khalthoum. There are also more suggestively sensual works: a bare-chested youth framed by a Cairo cityscape in Into the Night; a statuesque, bearded man silhouetted against the beautiful Shajarat al-Durr mausoleum; an inviting-looking soldier; a mustachioed charmer; a smiling ancient statue, in a painting called The Fatal Seduction of the Time of the Pharaohs; a shapely nude man.

Al-Jabri’s art, with its necessary discretion and delicacy, offers a vision of the erotic Arab that so entranced travellers like Lawrence of Arabia, whose Seven Pillars of Wisdom fascinated al-Jabri with its evocation of the author’s friendship with the young Dahoum. Al-Jabri himself eulogized ‘Sultry skin of every chocolate to café shade, ideal bodies of a smooth mercurial voluptuousness built for high speed action as for the steamy languor of the hammams’. But, like others who had a penchant for risky encounters with rough young men – one thinks of the Italian filmmaker and novelist Pier Paolo Pasolini and the Franco-Algerian poet Jean Sénac – al-Jabri met his fate in a paroxysm of lust and murder.

The difficulty of living as a homosexual in Middle Eastern countries was vividly illustrated in Alaa al-Aswany’s popular novel The Yacoubian Building (2002), in which the cultured homosexual editor meets a violent end at the hands of his lover. In a notorious real-life incident that took place in 2001, fifty-two Egyptian gay men partying aboard a disco boat in the Nile were arrested and charged with ‘habitual debauchery’; twenty-one were given the maximum sentence of three years in prison. The Saudi and Iranian regimes have put homosexuals to death, and according to Amnesty International two dozen homosexual men and youths were killed in post-’liberation’ Baghdad. Nonetheless, such tragedies do not seem to have extinguished a lively homosexual life in the countries where al-Jabri lived and painted.