Ihara Saikaku is a famed Japanese author of erotic literature. Born into a prosperous merchant family in Osaka, he went on to train as a poet, becoming a lay monk after the death of his young wife in 1675. A thousand-verse poem brought him recognition as a writer, after which he turned to prose fiction. The Life of an Amorous Man, circulated in 1682, recounts the adventures of a gentleman who had sex with 3,742 women and 725 young men over the course of sixty years. Saikaku followed up this volume five years later with a collection of stories about sex between men, called The Great Mirror of Male Love.

Saikaku’s stories cover a spectrum of homosexual life à la japonaise. There is wild lovemaking and unrequited love, and men who cruise along the byways and in the pleasure quarters of Kyoto and Edo (modern Tokyo). Merriment with boys forms one of the attractions of the ‘floating world’ of sensual delights. Men enjoy casual encounters or buy sex for a few coins (sometimes griping about rising prices). Others swear undying love to companions, take their own lives to avoid disappointment, or pay visits to the graves of departed lovers. Boys play tricks on suitors and wrap them around their fingers. Young men flirt and sleep together, but two 60-year-old men have been bound in a union since adolescence. Speakers (sometimes in a decidedly misogynist accent) vaunt the superiority of boy love, and even a male doll looks for a male lover. One character confesses that ‘in my 27 years as a devotee of male love I have loved all sorts of boys, and when I wrote down their names from memory the list came to 1,000’ – testimony, at least, to a prodigious power of recall.

The entertainment district of a Japanese city, early 19th century (Musée Guimet, Paris)

Some of Saikaku’s tales are on an operatic scale. In one, Korin, the handsome, kindly son of a masterless samurai, is introduced into the house of a lord. ‘The boy’s hair gleamed like the feathers of a raven perched silently on a tree’ (in Paul Gordon Schalow’s translation), ‘and his eyes were lovely as lotus flowers.’ The lord quickly beds him. Korin refuses to return his affections, but the lord’s attachment only grows stronger when Korin slays a goblin. The youth, on the other hand, has fallen for Sohachi, the son of a military officer, and sneaks out of his host’s bedroom in order to consummate his desire. ‘In their passion, Korin gave himself to the man without even undoing his square-knotted sash. They pledged to love each other in this life and the next.’ A spy informs on him, however, and the infuriated lord forces Korin to confess, hacking off the arms with which he embraced Sohachi and slashing off his head. Sohachi, in revenge, kills the man who revealed their affair. After assuring the safety of Korin’s mother, he goes to Korin’s grave, sets up a signboard recounting their love, and commits ritual suicide, using the sword to cut the marks of Korin’s family crest into his stomach. Villagers decorate the site in honour of the lovers.

Japanese culture exhibited a tolerant, even celebratory, attitude towards intimate relations between men long before the time of Saikaku. The saintly Kūkai (Kōbō Daishi) (774–835), a poet, scholar and the founder of a major branch of Buddhism, is widely thought to have had intense romantic attachments to other men at his monastery on Mount Kōya. According to legend, he introduced homosexual behaviour to Japan after a pilgrimage to China. In one episode from the most famous of all Japanese works, the 11th-century Tales of Genji, the hero cannot make love to a woman he desires, so finds satisfaction with her brother instead. Another medieval classic, Kenkō Yoshida’s Essays in Idleness, speaks of the beauty of young men and of their companionships with scholars and priests. The most famous author of haiku, Matsuo Bashō, reminisced about his fondness for young men. A book published in the same year as Saikaku’s Great Mirror, by Hanbei Yoshida, provides advice to young men about hairstyles, cosmetics and other ways of making themselves attractive. In 1713 what is perhaps the world’s first anthology of homosexual erotic literature was published, and by one count six hundred works dealing with same-sex relations appeared during the Tokugawa period (1600–1868).

The terms nanshoku (‘male colours’) or wakashudō (‘the way of [loving] boys’) represent the tradition of erotic liaisons between an adult man (the nenja, who in principle took the active sexual role) and an adolescent – a practice particularly common in the monastic and samurai worlds. The age difference might have varied in practice but, according to convention, when a young man reached around 18 years of age he donned different robes and had his pate shaved. Having thus entered adulthood, he ceased to be the younger partner and began to find wakashu of his own. ‘No youth, even one who is happy without a lover, should refuse a man who expresses a sincere interest in him,’ counselled one writer, and even most shoguns openly engaged in such liaisons.

Although hierarchical and asymmetric, these relationships – as the historian Gregory Pflugfelder has pointed out – involved more than just the breathless lovemaking depicted in literature and art. A Confucian metaphor often employed by the Japanese was of brotherhood: the senior partner should treat the younger as his benevolent mentor, passing on values and skills. Some couples swore oaths to each other, exchanged tokens of their affections, and occasionally engaged in self-mutilation – scarifying themselves, or cutting off a finger-tip – to prove their devotion. Most partnerships lasted for a limited time, but the fleeting nature of the young men’s charms, destined to fade as the youths grew older, and the sense that lust and love between two people would change just like the seasons fit into the mainstream Buddhist notion of the transitory nature of beauty and pleasure.

Pflugfelder emphasizes that romantic and sexual engagements were more a question of accepted behaviour and pleasure than of identity. Men and youths contracted varied bonds, and most (there were a few declared women-haters, called onnagirai) married and fathered children. Same-sex love was not a free-for-all: although homosexual acts incurred no social disapproval, the authorities took pains to uphold propriety, issuing regulations to control male prostitution and the behaviour of ‘kabuki boys’ (apprentice actors who sometimes sold their sexual services) and the travelling actor–prostitutes known as ‘fly-boys’. Ironically, the prohibition against women appearing on stage, enacted in 1629, meant that female roles were played by specialized male actors (onnagata) who, along with shop workers, incense-peddlers, pages, priests’ attendants and sandal-bearers, were generally considered to be available for sexual encounters.

Tokugawa Japan was not a homosexual paradise, but few historical societies (with the exception of ancient Greece) seem to have been so welcoming of same-sex practices. One denizen of the pleasure quarters of Kyoto sighed in Saikaku’s book: ‘We were fortunate enough to be born in a place where boys are available for us to do with as we please. As connoisseurs of boy love, we cannot help but pity the rich men of distant provinces who have nothing half as fine on which to spend their money.’ It is no surprise that the first European visitors to Japan in the 16th century, entranced by the country’s aesthetic attractions, expressed shock at such mores.

A new genre of literature emerged in late 19th-century Japan: ‘girls’ fiction’ (shōjo shōsetsu), sentimental writings destined for girls between the age of puberty and marriage. One of the most celebrated practitioners was Nobuko Yoshiya, whose works, like her life, reveal her lesbianism.

Yoshiya was born in Niigata prefecture, into a family with samurai ancestry. Since her father was a civil servant, she moved around frequently during her childhood. She began writing in her teens, specializing in stories and serialized novels that first appeared in periodicals. By the 1930s, she was the highest-paid writer in Japan, earning three times more than the prime minister (her success allowed her to build eight houses and to keep six racehorses). She was also a prolific writer: already by the end of that decade, Yoshiya had seen the publication of a twelve-volume anthology of her work. As a war correspondent, she filed reports from Japanese-occupied Shanghai and Manchuria, and various countries of South-East Asia, in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

Yoshiya’s first major work, entitled Flower Tales, comprised fifty-two stories and appeared between 1916 and 1924. Many were set in girls’ higher schools and told of intimate but doomed friendships between young women. The topic coincided with several social developments of the Taishō era. This was the time of the ‘modern girl, modern boy’ in Japan – a quest for modernity, and Western ideas and fashions, before the advent of authoritarianism and militarism in the 1930s. Schooling played a large role in the life of the ‘new woman’ in the early 20th century. There was also growing interest in sexology in this period.

Borrowing from the new Western concept of homosexuality – a word that they translated as dōsei ai – sexologists wrote positively about friendships between young women and between young men. They were generally less approving of physical relations between those of the same sex, however, even if some thought that hugging and kissing did no harm and might prepare girls for married life. Passionate infatuations with schoolmates or teachers were part of a global phenomenon: called ‘spoons’ or ‘raves’ in Britain, and ‘smashing’ in America, they formed the subject of the world’s first lesbian-themed film, the German Mädchen in Uniform (‘Maidens in Uniform’; 1931). Havelock Ellis’s essay on ‘The School-Friendships of Girls’ (1901) appeared in translation in a Japanese women’s magazine in 1914, the same year that another magazine reproduced sections of Edward Carpenter’s The Intermediate Sex (1906) (both periodicals had lesbian editors).

Nobuko Yoshiya, late 1930s (Private collection)

Young women’s crushes, such as those described by Yoshiya, were termed haikara (from the English ‘high collar’, or stylish) or denoted by the Western letter ‘S’ (from the English ‘sister’). They sometimes led to scandals or tragedies, as occurred in 1911 when two 20-year-old women from Yoshiya’s home province, lovers who were graduates of a Tokyo school, committed suicide by tying themselves together with a pink sash, weighting their kimono sleeves with stones and throwing themselves into the sea; they left a farewell note elegantly signed ‘Two Pine Needles’. The case attracted attention because of the young ladies’ elite background, and newspapers reported over three hundred other incidents of women who died in copycat joint suicides during the inter-war years.

Flower Tales thus appeared in a context of great social change and widening knowledge about same-sex romance. Michiko Suzuki, a professor of Japanese language and literature, provides an insight into Yoshiya’s work for the non-Japanese reader by explaining that, while chaste affections are presented positively, the mood usually turns melancholic or tragic: ‘Love is often unrequited, or even when it is reciprocated, the relationship is terminated due to a change of heart, separation, disease, or death.’ Yoshiya’s girls do not grow up into the ‘good wives, wise mothers’ that society expected, and remain nostalgic for the intimate friendships of a lost youth. This melancholy mood reflected a typical Japanese appreciation of what is transitory, be it the beauty of springtime cherry blossoms or a passing love.

Suzuki has discovered lesbian themes scattered throughout Yoshiya’s work. In ‘Yellow Rose’, for instance, a teacher tells a favoured student about her admiration for Sappho: ‘a person who gave her passionate devotion to a beautiful friend of the same sex and was betrayed’. Yoshiya’s novel Two Virgins in the Attic, published in 1922, concerns a romance between two women in a boarding house. It was based on Yoshiya’s own affair with a woman at the Tokyo YWCA – a ‘proving ground’ for lesbian relationships, according to the anthropologist Jennifer Robertson. For Suzuki, the work ‘challenged the conventions of girls’ fiction by celebrating a post-higher girls’ school love relationship’; it ends confidently, the women leaving their rooms to start a life together as a couple. Suzuki further remarks that Yoshiya’s writing style, with its ample sprinkling of ellipses and dashes, and its use of language that was traditionally both male and female, regularly transgresses gender norms.

From 1925 Yoshiya edited a short-lived journal called Black Rose, which published feminist works criticizing patriarchy and sexism. The inaugural issue carried as a frontispiece a picture of ‘Sappho under the sea’, and included the first instalment of Yoshiya’s ‘A Tale of a Certain Foolish Person’. Suzuki provides a synopsis: Akiko, a 22-year-old teacher, falls in love with Kazuko, her 19-year-old student, who reciprocates her affection. Although troubled by her sexuality, Akiko affirms her identity: ‘It cannot be denied that mutual male–female love is the primary true way of humanity. But there must also be a secondary path; is this not a path that should be allowed for the small number who walk the way of same-sex love?’ Kazuko’s father, who is already arranging her marriage, blames the teacher for making his daughter lovesick. Kazuko graduates, and a disconsolate Akiko resolves to leave town. The story ends shockingly when Kazuko is found raped and murdered by a man. Akiko faints at the news, hearing a voice calling out, ‘thou foolish one’.

The titles of other stories – ‘Husbands Are Useless’, for instance, or ‘Female Friendship’ – intimate women-centred themes, although Yoshiya wrote historical novels and much non-fiction as well. In 1935 a silent film was made of her story ‘Pheasant’s Eyes’, which tells of a relationship between an adolescent girl and her sister-in-law. She also collaborated with the Takarazuka Revue, an all-female musical theatre troupe.

Yoshiya’s partner for almost fifty years was Chiyo Monma, a mathematics teacher she had met in 1923, when Monma was 23 and Yoshiya 27 years of age. They had a passionate courtship – the letters they exchanged when Monma was teaching for a year in Shimonoseki are filled, Robertson says, with steamy sexual content – and began living together in 1926. Monma looked after the couple’s house, business affairs and entertainment. To ensure that Monma would be her heir, Yoshiya legally adopted her. Yoshiya’s diary reveals her affection: ‘Chiyo, on your birthday, I give thanks to fate which gave this person to me.’ After Yoshiya died – Monma holding her hand – Monma told a journalist: ‘Even in her old age, Ms Yoshiya remained in pursuit of the sweet fragrance of her girlhood dreams. Perhaps that is what attracted me.’ Yoshiya provided a suitable epitaph for herself: ‘There is nothing shameful about loving someone, nor about being loved by someone.’ The house that the two women shared in Kamakura is now the Yoshiya Nobuko Memorial Museum.

Sado, a novel written by William Plomer in 1931, is the story of Vincent Lucas, a young Englishman and aspiring painter, who journeys to Japan. On the ship, he makes friends with the captain and a radio officer, whose conversations begin to teach him about this strange new world. Once he arrives, Lucas meets an English woman, Iris Komatsu, the wife of a Japanese man, and the Komatsus offer him their garden house to use as a studio. Lucas also meets Sado Masaji, a handsome and warm, if somewhat melancholy, country boy who has come to the city to study. Iris Komatsu disapproves of him, although the young man is an acquaintance of her husband. Iris gradually falls for Lucas. He, however, draws closer to Sado, who moves in with him. Sado poses for him, and they enjoy long talks, travel together and become intimate – the author just hinting at a sexual consummation of their friendship as they disappear together into the woods during a picnic. A European woman friend of Lucas’s visits and tells him that it is time for him to return to England; Lucas reluctantly agrees. He realizes that, despite his love for Japan and for Sado, he can never make the country his home. He and a forlorn Sado sadly shout ‘Sayonara’ to each other as the ship pulls away from the dock.

Virginia Woolf, whose Hogarth Press published Sado, confessed that she did not really care for the novel, and Stephen Spender judged, rather unfairly, that it did not confront what he called ‘real values – food, fucking, money and religion’. Some of Plomer’s acquaintances felt that he was too timid in his portrayal of the erotic friendship between Lucas and Sado, but E. M. Forster, a longtime friend of Plomer in the Bloomsbury set, thought highly of it. The book remains a carefully drawn picture of Japanese life, a thoughtful meditation on the attractions, but also the difficulties, of homoerotic intimacies across borders, and a reflection of Plomer’s own experiences in Japan, where he had lived and taught from 1926 to 1929.

William Plomer, c. 1930 (Reproduced by permission of Durham University Library [plomer.ph.b1.14])

Born in the Transvaal, in South Africa, to English parents (his father was a colonial official), Plomer was educated at a school in Johannesburg and at Rugby in England. He returned to South Africa to work on a sheep farm in the Cape, and then, from 1922 to 1925, in a trading store on a Zulu reserve in Natal. His first novel, Turbott Wolfe (1926), for which he drew on his experiences, tells the story of an interracial marriage; it shocked many readers in South Africa, where racial segregation was the norm.

Along with two others, in 1926 Plomer set up the bilingual literary and political journal Voorslag, to be a liberal and anti-racist voice in South Africa. One of his collaborators was the Afrikaner journalist Laurens van der Post, who had defended two Japanese journalists against a racist coffee-shop owner in Pretoria. By way of thanks, he was offered a trip to Japan and invited Plomer to join him.

Just like Lucas in his novel, Plomer made friends with the captain, Katsue Mori. Mori was the descendant of a samurai family and a former national kendō (fencing) champion; he was an attractive, well-built man, but Plomer’s interest was in the captain’s insight into Japanese culture and politics. Mori provided a warm reception for the visitors, and would keep up a correspondence with Plomer for the rest of his life. As the tour of Japan came to an end and van der Post prepared for departure, Plomer decided to remain.

Plomer found a job teaching at an English-language school before transferring to an elite institution that prepared students for entry into the Imperial University. He was a successful and popular teacher, and the institution’s ambience encouraged extra-curricular contacts between teachers and students, one of whom became his companion and factotum. It is possible that Plomer, who was still probably bisexual, had brief affairs with a couple of other pupils. On a field trip to a mountain resort, he drew particularly close to Morito Fukuzawa, a farmer’s son who became his housemate. Fukuzawa introduced Plomer to the classics of Japanese literature, and together they hosted sake parties for friends. Throughout his life and writings Plomer was discreet about his sexual and romantic life, but it seems that he was in love with Fukuzawa: ‘We understood each other, we were used to each other, we were fond of each other … We had lived on terms of close friendship under the same roof, and had travelled about the country together, understanding one another perhaps as nearly as the barriers of tradition, race, love and education would allow.’

Plomer decided he could not stay forever in Japan, and in 1929 returned to England. There he continued to publish novels, poetry and works of non-fiction (including a biography of Cecil Rhodes), and worked as reader for a publisher, where he discovered such new talents as Ian Fleming, of James Bond fame. He also wrote several librettos for Benjamin Britten, including Curlew Beach, which is based loosely on the plot of a Japanese Nōh play. He spent the last decades of his life in a relationship with Charles Erdmann, a German refugee whom he had met during the Second World War.

Despite repeated invitations to visit and teach there, Plomer never again set foot in Japan, but the country remained a strong and happy memory. ‘Japan was my university,’ Plomer recollected. In Japan – so different from the country of his birth – he said that he was ‘able to do what I had always wanted to do and never could in Africa, that is to say, to live at ease with people of an extra-European race and culture’. The experience ‘helped me to understand that Europe was not everything, and to see Europe from a distance through Asian eyes’. Recalling Mori, Fukuzawa and his life in Japan, he concluded: ‘Civilisation has many dialects but speaks one language, and its Japanese voice will always be present to my ear, like the pure and liquid notes of the bamboo flute [shakuhachi] in those tropical evenings on the Indian Ocean [during the journey to Japan] when I heard it for the first time, speaking of things far more important than war, trade, and empires – of unworldliness, lucidity, and love’.

Other homosexuals followed in Plomer’s wake to Japan, including such writers and teachers as James Kirkup, John Haylock and Donald Keene. Donald Richie’s Japan Journals record his own adventures and those of many visitors who were fascinated by Japanese culture and appreciative of the Japanese perspectives on sex and love.

In his 1949 novel Confessions of a Mask, Yukio Mishima writes autobiographically about youthful sexual desires and fantasies. His 4-year-old self is fascinated by a swarthy man removing nightsoil. The smell of sweat from a passing parade of soldiers arouses ‘a sensuous craving’. Dressing up as a child, he is interested in princes, and is ‘all the fonder of princes murdered or princes fated for death. I was completely in love with any youth who was killed.’ He fantasizes about men at the seashore and at the baths, and about the figures painted on Greek vases. Guido Reni’s painting of St Sebastian – the beautiful martyr pierced with arrows – becomes a personal icon. As an adolescent, he falls in love with a rustic student, obsessed by his strong muscles and the tufts of abundant hair in his armpits. He befriends a girl, but realizes that he feels no sexual passion for her; and a visit to a brothel proves his heterosexual impotence. Confessions of a Mask – not translated into English until 1958 because publishers found it too shocking – made Mishima a literary celebrity in Japan at the age of 25.

Mishima was the son of a government official and the grandson of a colonial governor, and was raised in Tokyo largely by a tyrannical grandmother of samurai descent who kept him isolated even from his own mother. He studied at the Peers’ School, a commoner in an academy for noblemen, where he graduated top of the class and received a gold watch from the emperor. By that time he was already a published poet, although his father, who thought writing effeminate and degenerate, occasionally tore up his manuscripts. Against the background of the Second World War – the grand designs of Japanese military leaders had come undone, the Americans had devastated Tokyo and atom bombs had destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki – Mishima continued his studies at Tokyo’s Imperial University and soon after the Japanese surrender took a law degree. He then entered the prestigious civil service, but resigned after a year to pursue a writing career.

Mishima’s other major book with a homosexual theme, published in Japanese in the late 1950s and one of the most important homosexual novels of the 20th century in any language, was Forbidden Colors. In this story of an ageing writer and a young man, the focus shifts from the individual ‘coming out’ of Confessions of a Mask to a community of men. ‘They are all my comrades,’ realizes the hero: ‘they are a fellowship welded by the same emotion – by their private parts, let us say. What a bond!’ Shunsuké, a womanizer and misogynist, seeks revenge on women; Pygmalion-like, he trains the godly Yūichi, a student sure of his own homosexual inclinations, to do the work. The novel, written in an almost documentary style, covers gay cruising in the toilets and grasslands of Ueno Park, nightlife in a Ginza bar called Rudon’s (modelled on a real place, called the Brunswick), bisexuality, liaisons between older and younger men (and between Japanese and foreigners), long-lasting partnerships and casual encounters, male prostitution, gay parties at rural retreats, and yearning reciprocated and rejected. It explores the spectrum of same-sex affections – lust, patronage, dreams of ‘marriage’ – through the troubled relationship between Shunsuké and Yūichi, which reflects that between Socrates and Alcibiades. Disquisitions on beauty, love and desire are infused with Zen sentiments, and the book alludes to sources as diverse as Winckelmann, Pater and medieval Japanese texts. Sex between men assumes the shape of a metaphysical, aesthetic and existential choice, with intimate friendships representing the ‘reconciliation of spirit and nature’.

Mishima published forty novels, eighteen plays, twenty volumes of stories and many essays. He starred in movies about a leather-jacketed gangster and a samurai assassin, and in 1966 made a horrifyingly exquisite film, The Rite of Love and Death, about a nationalist officer who commits ritual suicide – foreshadowing his own seppuku four years later. He went on world tours, sometimes accompanied by his wife, the daughter of an artist, and gave interviews in fluent English. Expatriates in Japan, such as Donald Richie, remembered him as elegantly courteous, charismatic, a dandy who used translators, photographers and editors to promote himself.

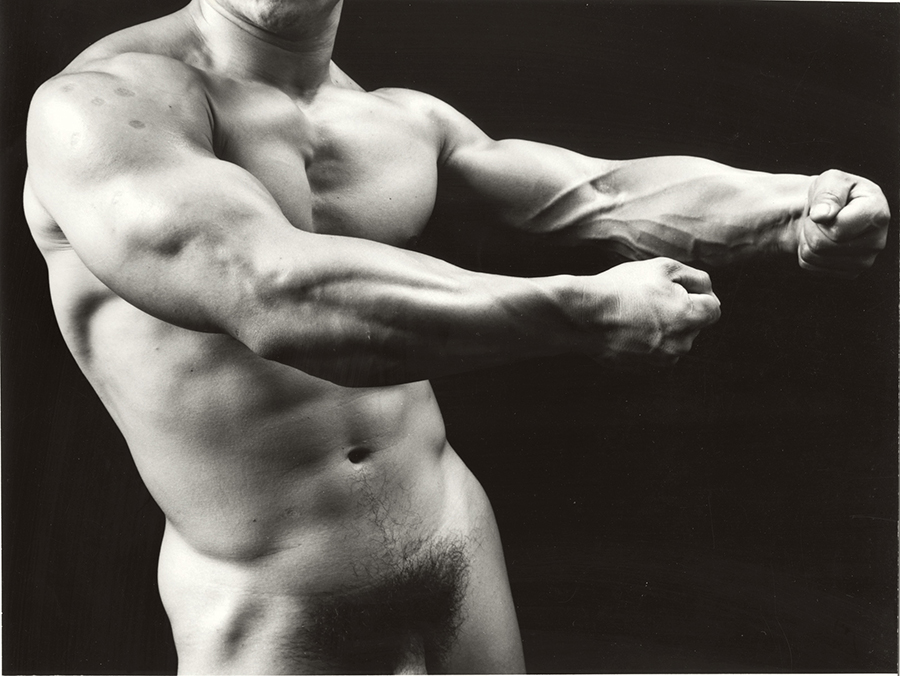

Mishima had been a pale, small and sickly young man, but from the early 1950s he re-created his body through weightlifting, bodybuilding and kendō (fencing), happily displaying his taut torso to photographers. He also frequented the gay bars of Tokyo, ostensibly doing research for Forbidden Colors. Occasionally there were liaisons; after Mishima’s death, his children sued one lover whose memoir about his affair with Mishima had included letters from the famous author without permission.

Although he had previously shown little interest in politics, towards the end of his life Mishima became increasingly immersed in Shinto mysticism, ultra-nationalism and emperor-worship – a reaction against modernism, Japan’s subjection to American overlordship, and the leftism that he feared would extinguish samurai virtues. In 1967 he enlisted in the Ground Self-Defence Force, and the following year swore a blood oath ‘in the spirit of the true men of Yamato to rise up with sword in hand against any threat to the culture and historical continuity of our Fatherland’. He organized a private militia, the Shield Society, which was fully equipped with uniforms and trained at boot camps.

In 1970 Mishima posed for a series of photographs called ‘Death of a Man’, for the magazine Blood and Roses, and worked on a novel of almost three thousand pages. After a last night spent writing the novel’s final words, he and a band of would-be warriors infiltrated an army building and tied up the commandant. Mishima emerged onto the roof to harangue soldiers and spectators who had gathered below, but fell silent after only a few minutes in the face of jeers. It was clear that his attempt to provoke a coup would come to nought. He climbed back inside, unbuttoned his tunic and slit his stomach with his sword. A disciple chosen to administer the coup de grâce – a young man, probably a lover, with whom he had taken a suicide oath – twice failed in his task, and another cadet was obliged to decapitate Mishima.

Mishima’s gruesome, comic-opera demise hardly left a joyful testament. For his friend Donald Richie, ‘His may have been a political statement, an aesthetic statement, but it was also a despairing personal statement.’ Mishima’s gesture seems grandiose, but in a pathetic way. Psychologists may muse on its relation to his childhood, success, sexuality, the disappointment he felt at not winning a coveted Nobel Prize, or his regret at not having fought in the Second World War. Was it an act of misguided heroism or of ultimate exhibitionism, the destruction of his perfected body and his career at their zenith?

Western audiences greeted Mishima’s unsettling works with acclaim. For homosexuals his life and work had a particular resonance: some recognized the sadomasochistic tendencies, but many others looked to the chronicles of sexual awakening, his stripping away of masks, the avowal of homosexual desires, the encounters, the references to Wilde and Huysmans, Antinous and Endymion, the cult of the strong male body. In the mid-20th century, he was the best-known voice of homoerotic passion from outside the West, and his romantic and tragic scenarios remain a testimony to his genius.

Two photographs of the author Yukio Mishima appear in Tamotsu Yato’s album Young Samurai: Bodybuilders of Japan, published in 1967. In one image, Mishima, dressed only in a loincloth and holding a sword, sits tautly on a tatami mat in a Japanese room, in front of a scroll showing a painting of a large bird of prey. Mishima also contributed the introduction to the book, somewhat disingenuously saying that the pictures of him provided an imperfect exception to the panoply of impeccably toned and muscled bodies. Mishima lauds bodybuilding, evoking classical Greece and ancient Japanese mythology and bemoaning the lack of a modern tradition of physique development in Japan. He credits bodybuilding to American influence, and intimates that such exercise could rejuvenate and revivify Japan.

Yato’s bodybuilders are all cast in the American mould: they have overly muscular, oiled bodies and strike the poses characteristic of the ‘physique pictorial’ magazines that were popular with American homosexuals looking for snapshots of naked men in the 1950s. Captions give the names, ages, professions, sporting affiliations, height and weight of the musclemen. Almost none of the men in the pictures are shown against recognizably Japanese landscapes, but several are photographed inside a stadium – a reminder that Tokyo hosted the Olympics in 1964.

Tamotsu Yato, Mr Japan – Takemoto Nobuo, 1971 (Collection Gallery Naruyama, Tokyo)

Tamotsu Yato, 1956 (Personal collection of Donald Richie, 1956)

Several years after the appearance of Taidō (‘The Way of the Body’) – as the book was titled in Japanese – Yato published Naked Festival (1968; Hadaka Matsuri, 1969), again introduced by Mishima. Yato here directed his camera at the bodies of young men, who generally wore only a fundoshi (cotton loincloth) but were sometimes naked, as they participated in the rural festivals (matsuri) that marked harvest-time and the arrival of the new year in Japan. Traditionally the festivals included moments of ritual purification and Shinto observance, but they were also joyous village fêtes, in which young men processed in streets, carrying torches and mikoshi (ornate portable shrines), competed for ritual balls or talismans tossed by the priests, or ran through the snow and plunged themselves into freezing water – rites of passage and displays of virility emboldened by copious quantities of sake. The festivals had no erotic intent; as one of the ethnographic essays in Yato’s book points out, nakedness carried no shame in old Japanese culture, and the fundoshi did not so much hide the men’s private parts as protect them with a symbolic garment.

The bodies of Naked Festival are not the barbell-sculpted forms of Young Samurai, but the sleek, toned young proletarians or salary-men of provincial Japan, sweatily climbing over each other to grapple for prizes, massed together with entwined arms in a spirit of camaraderie, or stoically shivering in the winter sea. The anthropological essays underline the cultural significance of the matsuri, and Mishima’s text laments the decline of such venerable celebrations, owing to Westernization and its puritanical attitudes towards even ‘sacred nakedness’. ‘Here we find none of those pitiable Japanese who commute in crowded subways to air-conditioned offices … Blue-collar workers from huge factories, bank tellers, construction workers – they have bravely cast aside all clothing in favor of the ancient loincloth, they have reclaimed their right to be living males.’ For both Mishima and Yato, these gatherings were something primal, proudly primitive: a festival of virility and joy. To viewers, Naked Festival represents a documentary record, a photographic exercise, and a celebration of beautiful Japanese youth. Indeed, the author Donald Richie has suggested that the young men’s ‘erotics are emphasized’. Echoing Mishima’s view of the desires exhibited here, he adds that ‘Yato goes through an adult erotics to return to something like an adolescent innocence.’

Yato’s third and final book was Otoko (1972) – the word means ‘man’, but can also signify ‘lover’ – which he dedicated to the memory of Mishima. In this volume he compiled eighty-one photographs of fifty-one men, most around 20 years of age. Though they are fit and handsome, they are not bodybuilders or festival-goers, but young men posing for photographs solely because of their beauty. They are either nude or wear just a fundoshi or a yukata (light cotton robe). All are Japanese, as are the props: a warrior’s helmet, a parasol, a screen painting, noren curtains, a katana sword, a tea service. Yato’s work here constitutes a vision of Japan, its culture and its arcadian landscape. But Western references appear too: one young man holds a Wildean lily; another lies supine like a mock bloodied St Sebastian, pierced in the groin by an arrow. These pictures are also more explicitly erotic than in Yato’s previous books: one boy rummages in his fundoshi; bodies enfold; a head is cradled in a lap; a face moves down a belly; a youth presents himself on a bed. The homosexual sensibility glimpsed in Young Samurai and Naked Festival is now more open: one wonders what Yato might have attempted in the next volume he was planning.

Yato was born in Nishinomiya, near Osaka, in 1928. He worked as a dancer until an automobile accident made it impossible for him to continue his career. In one of Tokyo’s homosexual haunts, in the early 1960s, he met an American expatriate publisher, Meredith Weatherby, who was also a translator and friend of Mishima. They became lovers, and Yato served as Weatherby’s factotum. Weatherby encouraged his photography and was credited as ‘producer’ of his three books. After they broke up in the early 1970s, alcohol and tobacco aggravated Yato’s heart condition, which led to his death in 1973.