On 19 September 2010, Pope Benedict XVI beatified the English cleric John Henry Newman, for his holy life, works of faith and the requisite performance of a posthumous miracle. This makes the ‘Blessed’ Newman an object for prayer and veneration, and places him on the path to full canonization in the Roman Catholic Church. The pontiff paid tribute to Newman’s ‘long life devoted to the priestly ministry, and especially to preaching, teaching, and writing’.

In his homily, the pope said little about Newman’s personal life and did not mention his friendship with Ambrose St John. One of Newman’s most recent biographers, John Cornwell, quotes some of Newman’s comments about the fellow Oxford-educated scholar, convert to Catholicism and priest who for many years lived with Newman and other clerics at an oratory in Birmingham: ‘As far as the world was concerned I was his first and last’, and ‘From the very first he loved me with an intensity of love, which was unaccountable.’ He was ‘Ruth to my Naomi’. When St John died, Newman confessed: ‘I have ever thought no bereavement was equal to that of a husband’s or wife’s, but I feel it difficult to believe that any can be greater, in any one’s sorrow, greater than mine.’ In accordance with his ‘imperative will’ and ‘command’ (his words), Newman was buried in St John’s grave after his death.

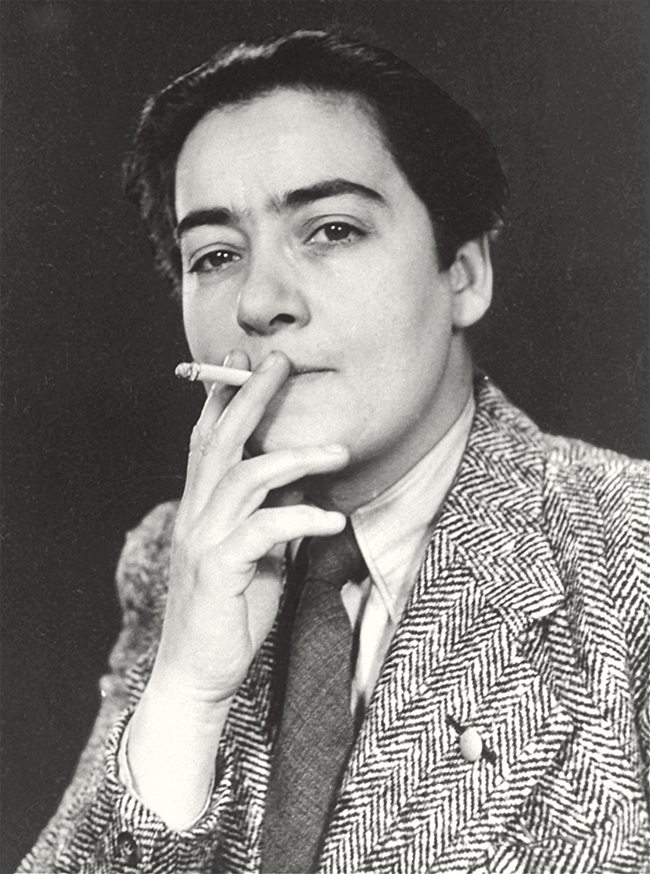

Cardinal Newman in a portrait by John Everett Millais, 1881 (National Portrait Gallery, London)

Contemporaries remarked on a certain gender ambivalence, even effeminacy, displayed by the young Newman. One described his community of Oratorians as inhabited by ‘old women of both sexes’. Cornwell notes that the ‘unaccountable’ special friendship with St John caused some in the Church hierarchy to remonstrate. Newman replied, beautifully, of his friendship: ‘I can do nothing to undo it, unless I actually did cease to love him as well as I do.’

In a review of Cornwell’s biography, the philosopher Sir Anthony Kenny comments that the question of whether Newman was gay is anachronistic: ‘Nineteenth-century Anglicans and Catholics did not classify themselves in accordance with forms of sexual orientation’. For celibate priests, any sexual act would have been a grave sin, and sexual emotions represented temptations. He continues: ‘I do not know whether those who wish to set up Newman as a gay icon believe that he was homosexually active, but any suggestion that he was is absurd.’ He suggests that the Christian prohibition of homosexuality promoted a different sort of intimacy between men and the effusive expression that it engendered.

Newman’s life spanned almost the full 19th century. Born the son of a prosperous banker in London (his father later went bankrupt, however), he was educated at Trinity College, Oxford, though a breakdown during his examinations meant that he graduated in 1821 with only lower second-class honours. He nevertheless won election to a fellowship at Oriel College. Newman was ordained as an Anglican priest in 1825, and then became the curate of an Oxford church. From this point on he gained a reputation as one of the city’s best preachers.

His closest companion at the time, also a fellow at Oriel, was Richard Hurrell Froude, the son of an archdeacon. Cornwell notes: ‘Newman wrote that the attachment developed into “the closest and most affectionate friendship”’. (Froude’s journal contains enigmatic hints of his own sexual guilt, especially about feelings for one male pupil.) The two travelled happily through the Mediterranean in 1832. Froude’s death from tuberculosis four years later left Newman greatly distressed. He memorialized this early friendship in a poem called ‘David and Jonathan’, which was headed with the biblical epigram about love ‘passing the love of women’: ‘Brothers in heart, they hope to gain / An undivided joy’.

In 1833 Newman became involved with the Oxford Movement, a group of churchmen who saw the Church of England as but one branch of the universal Catholic Church, and who wanted to move it away from Protestant ‘Low Church’ liturgical practice towards a celebration of the ‘beauty of holiness’. Under Newman’s direction, the Tractarians (as they came to be known) published a series of religious pamphlets. In one of these essays, written in 1841, Newman argued that the Thirty-Nine Articles, which historically had provided the basis for Anglican Protestant doctrine, did not constitute a wholesale refutation of Catholicism – a viewpoint for which he earned a rebuke.

Newman soon began to withdraw from Anglicanism. He set up a small community of like-minded priests, including St John. In 1843 he resigned his Anglican appointment, and two years later was received into the Catholic Church and ordained a priest in Rome. He then moved to Birmingham and set up an oratory in Edgbaston. In the early 1850s, for a period of four years, he was the rector of the Catholic University of Ireland (the future University College Dublin); one of his most enduring and eloquent works is The Idea of a University (1852). In 1878 his old college at Oxford, which only in the previous decade had begun to admit Catholics to read for degrees, elected him an honorary fellow.

Newman wrote brilliantly on many aspects of religion and epistemology, and was also a fine poet. His collected works, including letters and diaries, stretch to dozens of volumes. His Apologia Pro Vita Sua (1864) is considered one of the classics of autobiography. Newman was not afraid to take a stand on issues, such as the role of the laity and papal infallibility, that sometimes put him at odds with the Vatican. He denied being a liberal, although ultramontane opponents considered him as such. On the other hand, his writings show no opposition to progressive ideas like evolution, which others considered anathema. In 1879 the relatively modern Pope Leo XIII elevated Newman to a cardinalship, making him a prince of the Roman Catholic Church.

Strands of homosociality and homoeroticism weave through 19th-century Anglo-Catholicism and Roman Catholicism, from celebrations of spiritual friendship to emotional verses about choirboys. The poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, for instance, fell in love with an adolescent named Digby Dolben. It was Newman who received Hopkins into the Catholic Church when he converted from Anglicanism (he later became a Jesuit priest). The priesthood, whether Catholic or Anglican, offered a career for the religiously inclined that provided shelter, a learned profession and the comfort of camaraderie with other men. Despite its damnation of homosexuality, Christianity offered the consolations of model friendships between saints, the affection of Christ for his followers, and the sometimes sexually charged imagery of heroes and martyrs of the faith. The precise nature of the relationships between priests is unknowable, but the significance of affective attachments for men like Newman is undeniable. The church’s obsession with sex perhaps helps explain why the idea of erotic feelings within the clergy creates such discomfort.

It is generally admitted nowadays that many Catholic priests – at least in the desires of the mind, if not the sins of the body – are homosexually inclined. Thousands of cases of sexual abuse by priests and teachers in Catholic schools have come to light in recent years, involving young people of both sexes; they have shown that, within the context of enforced celibacy, a much darker type of sexuality exists. In the same year as Newman’s beatification, and after the deaths of 25 million people from AIDS since 1981, Pope Benedict guardedly conceded that, in restricted circumstances, the use of condoms – the major preventive of HIV infection, but until then completely banned by the church – might be permitted for Catholics.

Rosa Bonheur’s intimate ties to two other women did not involve trauma, scandal or shame. Although her manly dress sometimes caused raised eyebrows – a provocation that she seems to have enjoyed – Bonheur did not really shock those around her, as did some lesbians and gay men of her time, either intentionally or unwittingly. She lived her life largely outside public circles of sexual nonconformists. A critic has to look hard to find evidence of women-oriented attachments in her artwork.

Bonheur was born in Bordeaux in 1822 to a moderately successful painter father and a mother who hailed from a well-to-do merchant background. Seven years later the family moved to Paris, where they established themselves with some difficulty and lived in genteel poverty. After a brief and unhappy apprenticeship as a dressmaker, Bonheur began to study art with her father (her brothers and sister would also become artists). By the age of 14 she was copying paintings and taking classes at the Louvre. In particular, she took an interest in the research on flora and fauna carried out at the Museum of Natural History, where her father was employed.

Bonheur began showing her paintings at the annual Paris Salon in 1841, at just 19 years of age, gradually winning critical acclaim for her landscapes and studies of animals. She scored a triumph in 1848, winning the salon’s gold medal, and was commissioned by the state to produce a work showing ploughing in the Nivernais region. The result was a grand, realistic painting – now in the Musée d’Orsay, Paris – that demonstrated her keen ability to portray farm animals. The bucolic vision of peasant life doubtlessly reassured Parisians during a turbulent political period.

Édouard-Louis Dubufe, Rosa Bonheur with Bull, 1857 (Château de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles)

To perfect her technique as an animalière, Bonheur examined butchered animals at slaughterhouses, having secured permission from the Paris police to wear men’s clothes in that unusual – and, for most women, disagreeable – environment. But she also journeyed to the countryside to study living creatures, and in Paris itself frequented the horse market near La Salpêtrière. Her visits there inspired a massive painting now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: The Horse Fair (1853), which is arguably the most significant work by a woman painter in mid 19th-century France. It dramatically pictures a dozen white, brown and black horses; handlers struggle to control them as they nervously push, rear up and run across the dust, against a backdrop of plane trees and the cupola of the Salpêtrière hospital.

Bonheur felt a mystical personal connection with animals – which did not prevent her from either eating meat or being a good hunter – and they became her passion. Even in Paris, she filled the family apartment with pets, including a sheep; and once she was successful enough to own country estates, her menagerie encompassed horses, goats, sheep, moose, an otter and several lions (photographs show her fondly petting a lioness in her garden). When a colleague painted her portrait, she asked him to replace the table on which her arm was resting with the head of a bull. Bonheur became the painter of realistic animals in mid 19th-century France, and horses remained a speciality. After seeing one of Buffalo Bill’s ‘Wild West’ shows at the 1889 Paris Exposition, she enlarged her repertoire to include Native Americans and their horses as well.

Bonheur earned fame and made a great deal of money. She enjoyed the patronage of Emperor Napoleon III, whose consort personally decorated her with the Légion d’honneur – the first time it had been awarded to a woman artist – and her works sold well, particularly in Britain and the United States. Her style, however, evolved little, and she took almost no notice of new artistic currents, so that by the last years of her life the French public and art market had lost much of their interest in her work, considering her a painter of technically proficient but rather spiritless beasts and nostalgic rural scenes. Of her early success, Ploughing at Nivernais, Cézanne paid a backhanded compliment in calling it ‘horribly like the real thing’.

As a child, Bonheur had met Nathalie Micas, the daughter of another painter. After the deaths of her parents, she moved in with the Micas family, and on his deathbed Nathalie’s father enjoined the two young women to look after each other. Over the years they grew closer, at some point becoming partners, and they remained with each other until Micas’ death in 1889. When Bonheur earned enough to rent an apartment, Micas moved in (initially bringing her mother along). In time she bought a chateau outside Fontainebleau, where the three women continued to live together, and built a villa near Nice. Whether she and Micas had a sexual relationship is unknown; Bonheur once told friends that she was not the marrying type, and commented that ‘in the way of males, I like only the bulls I paint’.

Occasionally the male attire in which Bonheur wandered around city and countryside surprised her neighbours. She wrote wittily to her sister about the good people of Nice: ‘They wonder to what sex I belong. The ladies especially lose themselves in conjecture about “that little old man who looks so lively”. The men seem to conclude, “Oh, he is some aged singer from St Peter’s at Rome who has turned to painting in his declining years to console himself for some misfortune.”’

Micas did the underpainting on Bonheur’s works, kept house and tended to the animals. She was also an inventor, although her prize design – a brake for railway engines – failed to attract investors. The two regularly travelled around the French provinces and to Britain. They received well-known guests who admired Bonheur’s art, such as the emperor of Brazil. After Micas died, Bonheur wrote: ‘Her loss broke my heart, and it was a long time before I found any relief in my work from this bitter ache … She alone knew me, and I, her only friend, knew what she was worth.’ Micas was buried in Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

Shortly afterwards Bonheur met a young American painter, Anna Elizabeth Klumpke; nine years later they met up once again, when Klumpke painted Bonheur’s portrait. The two women grew very close during the sitting: indeed, Klumpke installed herself in Bonheur’s house almost immediately. Bonheur announced that they had decided to ‘associate our lives’ and told Klumpke: ‘This will be a divine marriage of two souls.’ They lived together for the last decade of Bonheur’s life, and Bonheur made Klumpke her sole heir. Bonheur’s will instructed that she was to be interred in the same vault as her beloved Micas, in Paris. When Klumpke died in 1942, her ashes were also entombed alongside.

This ‘woman-centred woman’ was the most important female artist of her day, and one of Europe’s greatest painters of animals. She was decorated by the governments of France, Spain, Belgium and Mexico, and given membership to numerous artistic societies (as well as the French Society for the Protection of Animals). Bonheur challenged stereotypes about women in her profession. She was not an artistic or political radical, but in her own way she was a feminist: ‘I have no patience with women who ask permission to think,’ she once wrote. Whatever the exact contours of her intimate partnerships, they represented significant emotional unions between women.

Military forces portray themselves as embodying the best of virtues, particularly those that are defined as traditionally masculine: fitness, discipline, loyalty, valour and comradeship. Those censorious of same-sex desire have often considered homosexuals bereft of these virtues; historically, they have feared that the presence of homosexuals in the armed forces might not only sap soldierly spirit, but also endanger the fatherland. As a consequence homosexual men and lesbians have been excluded from the armed forces in many countries, or allowed to sign up only if (as in the American case) they followed a path of self-denial embodied by the phrase ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’. Scholarly studies and veterans’ memoirs have shown, however, that many gay men and women have served with distinction, and that a subculture of homosexual contacts thrives, generally furtively, in barracks and on the battlefield. A French officer provides insight into this homoerotic culture.

Hubert Lyautey was born in Lorraine into a prominent family (his mother had aristocratic forebears) and graduated from France’s elite military academy. He developed a love for North Africa after being posted to Algeria as a young lieutenant, and was entranced by what he saw as the merit of France’s colonization, the beauty of the desert and the nobility of Arab warriors and nomads. A later posting took him to Tonkin, in present-day Vietnam, where his role was to advance the French conquest of Indochina. From 1897 he held command over a vast region of another new French possession, Madagascar, where his success brought him promotion to the rank of brigadier general.

When France established a protectorate over Morocco in 1912, Lyautey became the colonial pro-consul there, serving until 1925 (except for a brief stint as minister of war in 1916). Although he left that position with some bitterness, having been marginalized by another commander (the future head of the Vichy regime, Philippe Pétain) during the Rif War, Lyautey remained the most prominent colonial statesman in France. He rose to the rank of marshal, the highest in the army, won election to the Académie Française and organized a grand international Colonial Exposition in Paris in 1931. On his death three years later, he was honoured with a state funeral and buried, according to his wishes, in Morocco. His remains were transferred to Les Invalides in Paris and entombed near Napoleon’s after Morocco regained independence.

Lyautey’s penchant for handsome young officers was well known. His wife, whom he married when he was 45 years old, joked with his fellow officers that she had managed to cuckold them. A French minister, Georges Clemenceau, remarked crudely that Lyautey ‘always had balls between his legs … even when they weren’t his own’. Lyautey’s old foe Pétain, in the eulogy he delivered as minister of war in 1934, spoke more guardedly about his ‘romantic obsession’, ‘turbulent soul’ and ‘sometimes troubling caprices’.

The historian Christian Gury has argued that Lyautey was the model for the homosexual aesthete Baron Charlus in Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu (‘In Search of Lost Time’; 1913–27). The always dapper Lyautey was indeed a welcome guest at aristocratic and literary salons in Paris. He furnished his Lorraine chateau with a Moroccan room, and displayed trophies and souvenirs in what would now be seen as a very ‘camp’ style.

In his writings – he was a prolific author and a fine stylist – Lyautey enthused about classical statues he had seen in the museums of France and Italy, such as a youth who represented ‘a triumphal evocation of voluptuous and strong beauty’. Descriptions of Arab and African men reveal an appreciation of their seductiveness (he seems to have found the Vietnamese less alluring, however). He clearly enjoyed the homosocial camaraderie of military camps and garrisons, and in particular extolled the martial attraction of the youthful French soldiers with whom he liked to surround himself. He recounted, in veiled language, visits to his chambers by favourite subalterns. One was a ‘sub-lieutenant … who pleases me so much … [and] who came from ten p.m. to two a.m. to warm up my old thirty-year-old self with his hot and rich sap. What a young, vigorous and generous nature!’ Lyautey elsewhere maintained that ‘before ending the day, after the heavy quotidian tasks, nothing equals this happy bath of fertile and creative sap’.

Douglas Porch, a military historian, suggests that Lyautey’s homosexuality offended some fellow officers, ‘which is one of the reasons why he sought the company of writers, artists and left-of-center politicians … It also helps to explain why … he was so enthusiastic about colonial service.’ The colonial forces provided an outlet for many who did not ‘fit in’ at home, and Lyautey was far from the only French officer with homosexual tendencies. Another was Pierre Loti, a navy captain who served in Polynesia, Africa and Asia; like Lyautey, he was a flamboyant aesthete and a prolific author of novels, some of which had homosexual themes. A British example was Sir Hector Macdonald, a Scottish ranker and hero of the Anglo-Boer War, who rose to become military commander of Ceylon. Summoned for court martial on accusations of sexual misbehaviour with young men, Macdonald shot himself. Lord Kitchener and Lord Baden-Powell (the author of Scouting for Boys and founder of the Boy Scouts movement), both military heroes with probable homosexual inclinations, escaped Macdonald’s fate.

The army and navy have often excited the fantasies of homosexuals, and many (Oscar Wilde among them) have found that impecunious military men make ready casual partners. Sailors’ rugged masculinity has been a perennial theme in erotic art and literature. Billy Budd, for instance – a novella left unfinished at Herman Melville’s death in 1891 – deals with an officer’s sadistic obsession with a young rating, and its tragic consequences. It was transformed into an opera by Benjamin Britten in 1951 and recreated as a film (set in a French Foreign Legion camp) in Claire Denis’s Beau Travail (1999). Jean Genet’s lusty novel Querelle de Brest (1953) also centres on the image of the sexually potent sailor, as does the work of such artists as Jean Cocteau, Charles Demuth and Yannis Tsarouchis.

Frieda Belinfante was a Dutch musician, a pioneering woman conductor and a Resistance fighter in the Second World War. She was born in Amsterdam into a musical family: both of her parents were musicians, and her two sisters and brother also played instruments. She began to study the cello with her father, and gave her first public performance with him when she was still a child.

By the time she was a teenager, Belinfante was a promising young performer. She was also an active lesbian, having begun a seven-year affair with Henriëtte Bosmans at the age of 18. Bosmans, herself the daughter of musicians, was on the way to becoming a celebrated pianist and soloist with the Concertgebouw. Together with Belinfante and a flautist named Johan Feltkamp, they formed a chamber trio; in 1930 Belinfante married Feltkamp, but their union lasted only for six years, and Belinfante remained predominantly lesbian.

During the 1930s Belinfante’s musical career progressed. She played for several years with a Haarlem orchestra, but she also began to conduct – a rare and daring move into a career that was (and is) almost completely dominated by men. She took charge of two choirs: one from the University of Amsterdam, and a children’s choir. In 1938 Belinfante established a chamber orchestra, Het Klein Orkest, with whom she conducted works from both the classical and modernist repertoires. The following year she beat a dozen men to win a Swiss prize for conducting, and secured an invitation as guest conductor of the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, although the outbreak of the Second World War made it impossible for her to take up the engagement.

Frieda Belinfante (left) in Amsterdam, c. 1928 (Courtesy Frieda Belinfante/United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C.)

Frieda Belinfante, 1943 (Courtesy Toni Boumans/United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C.)

Belinfante’s father was Jewish, and her mother Christian, although the entire family was secular in outlook. After Germany’s invasion of the Netherlands, in May 1940, Belinfante was obliged to register with a Nazi-sponsored cultural organization. She refused and disbanded her orchestra. Before long she had joined an underground Resistance group, composed of about one hundred cultural figures, that forged identity cards for Jews. One of her fellow members was her friend Willem Arondeus, a painter, poet and author; Arondeus was gay, and had lived openly with his younger boyfriend for several years. Belinfante sold her valuable cello to the owner of the Heineken brewery in order to fund the group’s operations. She, Arondeus and the others hatched a plan to destroy the registry in Amsterdam that contained copies of all Dutch identity cards; its destruction would mean that the fake cards and passports that the Resistance were making could not be proved false. Arondeus and several others overpowered the guards and set fire to the building in March 1943. The group was betrayed, however. Arondeus and two other gay men were among those arrested, and a total of twelve – including Arondeus – were executed. Belinfante, now in grave danger, managed to escape to Switzerland, disguised in men’s clothing.

She remained a refugee there for the rest of the war. She returned home in 1945, but was disillusioned with Dutch life and in 1947 migrated to the United States. Having settled in California, she spent the next few years teaching music at UCLA, playing in Hollywood studio orchestras and giving private tuition. In 1954 she founded the Orange County Philharmonic Orchestra and became its conductor – the first permanent female conductor of a full-scale orchestra. It continued to give performances until 1962, when it dissolved on account of administrative and artistic disputes.

Belinfante passed the last decades of her life quietly, giving private music lessons, and died in retirement in New Mexico, where she had moved in the early 1990s. The year before her death, she gave an interview about her Resistance activities and musical career, which provided the basis for a documentary film, But I Was a Girl (1999). Klaus Müller – her interviewer, and the film’s assistant director – suggests that Belinfante’s lesbianism contributed to her earlier lack of recognition as a musician and as an active member of the Resistance.

Not all homosexuals have followed the straight and narrow. The criminalization of homosexual acts has meant that many over the ages have faced police and judges for their sexual behaviour, sometimes suffering dire penalties. But some homosexuals have also perpetrated ‘ordinary’ crimes: there are homosexual fraudsters, thieves, brigands and serial killers. Others have taken to a life of crime as a career choice, though perhaps only a psychologist could diagnose whether their sexual proclivities had any bearing on their professions.

One homosexual outlaw of a violent sort was Ronald (‘Ronnie’) Kray. Born in 1933 in Hoxton, east London, of Irish, Jewish and Romany descent, Ronald and his identical twin, Reginald (‘Reggie’) were the sons of a scrap-gold trader who himself sometimes appeared on police wanted lists. They were pure products of the rough-and-tumble working-class world of London’s East End, growing up in Bethnal Green and attending school in Brick Lane. The handsome young men both excelled as boxers – a traditional pursuit in their milieu – and fought professionally for a time. In 1952 they were called up for National Service with the Royal Fusiliers but deserted repeatedly, eventually finishing in jail awaiting court martial. Once they had been dishonourably discharged, two years later, they and their elder brother Charlie became involved in pretty crime, soon working their way up to more serious exploits, including protection rackets, arson, hold-ups and gambling. By the late 1950s the twins and their brother, who had surrounded themselves with a circle of motley villains known as the ‘Firm’, were well known in the London underworld. During the swinging sixties they operated a club in fashionable Knightsbridge, where they rubbed shoulders with international celebrities such as Judy Garland.

In 1960 Ronnie Kray earned an eighteen-month sentence in connection with a protection racket. In 1966, in the midst of a gangland war with another mob, Kray shot and killed a man in a Whitechapel pub who had allegedly referred to him as a ‘fat poof’. In 1968 the Kray brothers’ period of untouchability came to an end. On 8 May both twins were finally arrested (Ronnie was supposedly in bed with a young blond man when he was apprehended by police) and sent to jail for murder the following year. Ronnie died in Broadmoor secure mental hospital in 1995, having suffered from paranoid schizophrenia for many years. While in prison, he took up art as a hobby, and eight of his paintings, which were discovered in an attic in Suffolk, sold for £16,500 in 2008.

A police report from the 1950s – found in a Durham police station in 2010 – describes Ronnie as a man 5 feet 7 inches (170 centimetres) in height, ‘with a fresh complexion, brown eyes and dark brown hair’; it also noted that ‘Ronald Kray has been the leader of a ruthless and terrible gang for a number of years … he has strong homosexual tendencies and an uncontrollable temper and has been able to generate terror not only in the lesser minions of his gang, but also in the close and trusted members.’ The journalist and biographer John Pearson later wrote that Kray ‘liked boys, preferably with long lashes and a certain melting look around the eyes. He particularly enjoyed them if they had no experience of men before. He liked teaching them and often gave them a fiver to take their girl-friends out on condition they slept with him the following night … He never seems to have forced anyone into bed against his will and, as he proudly insisted, was free from colour prejudice, having tried Scandinavians, Latins, Anglo-Saxons, Arabs, Negroes, Chinese and a Tahitian.’

Laurie O’Leary, a childhood friend, remembered that Ronnie Kray considered bringing back to London an Arab boy he had fallen for on holiday in Tangier. Others recalled that he liked to show off his handsome young companions in smart London restaurants. O’Leary added that Kray seemed to be at ease with his sexuality, having already fallen in love with a boy when he was a teenager. Kray himself said he felt no shame in being homosexual: ‘There is nothing necessarily weak about a homosexual man – and I believe he does no wrong … I hate people who pick on homosexuals.’

Reginald Kray, who was bisexual, and the other members of the Krays’ gang, seem to have accepted Ronnie’s sexual interests with equanimity (perhaps by necessity). O’Leary clarifies: ‘Even if they objected, Ron just smiled at them and told them they didn’t know what they were missing.’ Kray’s father and elder brother did object, although his mother proved tolerant.

In 1964 the tabloid Daily Mail printed an article about a relationship between an outlaw and a Tory peer, without naming either man. Baron Boothby – a Scotsman educated at Eton and Magdalen College, Oxford, and a member of parliament before his elevation to a life peerage – sued the newspaper for libel. Boothby was known to be a philanderer, even earning the nickname ‘the Palladium’ (‘because he was twice nightly’) while at university. He had an affair with the wife of Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, married twice, and also enjoyed the company of boys. It seems that he had met Kray through an East End cat burglar who had been a sexual partner. According to some reports, Kray provided Boothby with a number of young men. Boothby settled his case against the Mail out of court and received a payment of £40,000 in damages. In 2009, however, the Mail revealed that newly found letters proved that Boothby and Kray shared rent boys and claimed that they contained information ‘too base to be revealed in detail’.

The scandal involved another friend of Boothby, allegedly known also to Ronnie Kray. Tom Driberg was a well-known and long-serving Labour member of parliament who had had several brushes with the law for ‘indecent assault’ and other homosexual offences. (Indeed, Winston Churchill is once supposed to have quipped: ‘Tom Driberg is the sort of person who gives sodomy a bad name.’)

The life stories of an East End gangster and two Oxonian parliamentarians could hardly have been more different, but their erotic interests drew them – and a cosmopolitan assortment of partners – into a network that existed on the fringes of legality (at the time, homosexual acts were criminal under British law). Driberg escaped prosecution largely because of his status and contacts, as did Boothby, while Kray’s conviction for murder – partly provoked by a homophobic comment – was a reward for a life of violent crime that had nevertheless made him and his brother into outlaw celebrities.

Many people in Anglo-Celtic countries have supposed that men who work in certain professions – interior decoration, floristry, window-dressing, hairdressing and fashion design among them – are gay. Although not all men in these fields are homosexual, of course, there may be a grain of truth to the idea that, at least until recent decades, men with homosexual inclinations often gravitated towards jobs where the type of machismo (real or affected) associated with typically ‘manly’ posts was not a prerequisite. Whether or not statistics bear this out, it is certain that some of the most acclaimed practitioners in the worlds of art and design have been gay.

A famed example is Yves Saint Laurent. He was born in 1936 in Oran, Algeria (then a French colonial outpost), where his father was a businessman. Saint Laurent moved to Paris after he had finished secondary school. When he was only 17 years old, his talent was spotted and he became an assistant to Christian Dior – a discreet homosexual who, shortly after the Second World War, had risen to the heights of renown as the inventor of the ‘New Look’ of womenswear. Saint Laurent assumed control of Dior’s fashion house when his mentor died, at the age of 52, in 1957. Three years later the French army called up Saint Laurent for military service, where, in a complicated turn of events, he suffered a mental breakdown. He was then dismissed by the Dior company in 1960.

Two years later, Saint Laurent established his own fashion business. His designs quickly catapulted him to fame, fortune and celebrity. His creation of the Rive Gauche line in 1966 – meant to exemplify the casual chic of Paris’s bohemian Left Bank – and his expansion into menswear in 1974, then into perfumery and accessories, made YSL a household name among shoppers. The status of the brand remained strong when Saint Laurent retired in 2002.

Two decades previously, in 1983, he had been honoured with the first solo exhibition devoted to a clothing designer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and in 2007 – the year before his death – the French government made him a grand officier in the Légion d’honneur, one of the country’s highest state awards.

In 1958 Saint Laurent met Pierre Bergé, a 28-year-old businessman who began to take over the running of his fashion business. The two were lovers and remained so for many years; soon before Saint Laurent’s death the men entered into one of the new French civil partnerships. Throughout their almost fifty-year friendship, they worked together as business partners. They also shared an apartment in Paris, a grand house – the Maison Majorelle, known for its exquisite gardens – in Marrakesh, and six other residences filled with an enormous collection of art and furnishings. Bergé has been a major supporter of French gay endeavours such as the magazine Têtu, and the AIDS groups Act-Up and Sidaction. He and Saint Laurent also lent their support to François Mitterrand, who won election as president of France in 1981 and whose government removed residual discriminatory laws against homosexuals from the French penal code.

By no means have all gay designers and their partners been as open about their sexuality, or as politically active, as Saint Laurent and Bergé. One whose legacy is very much associated with gay rights, however, is Rudi Gernreich. Born in Vienna in 1922, he fled Austria when the Nazis took power and settled in the United States. By the 1960s he had become a prominent designer, favoured by such clients as Jacqueline Kennedy. Gernreich’s long-term partner was Harry Hay, with whom he founded the most important early homophile organization in America, the Mattachine Society. Gernreich was listed in its membership rolls only as ‘R’, but provided considerable financial backing to the association.

Some homosexual designers are more open than others about their sexual preferences. The Italian Gianni Versace, who was assassinated in Miami by a serial killer at the age of 51, had a long relationship with a former model who now operates his own fashion company. In Britain two dressmakers to the queen – who were knighted for their services – were also known to be homosexual. These were Sir Norman Hartnell and Sir Hardy Amies. Always discreet, Amies had a partner for forty-three years. Of his friend and rival Hartnell, Amies once remarked wryly: ‘It’s quite simple. He was a silly old queen, and I’m a clever old queen.’

Did these designers’ sexuality have anything to do with their profession? The British ‘fashion knights’ were moderately conservative, but several of the others gained fame for daring designs that broke with tradition. Gernreich, who experimented with vinyl and plastic clothing and the ‘futuristic’ look, gained notoriety for his topless bikini – an unparalleled assertion of sexuality. Saint Laurent designed women’s outfits that crossed gender lines, such as his smoking jacket, pinstripe suits and pantsuits for women. Versace’s clothing for men, with its dramatic colours and styles, marked a departure from gentlemen’s traditional haute couture. Saint Laurent himself posed nude in an advertisement for his Pour Homme fragrance in 1971. Contemporary designers like Tom Ford, John Galliano, Jean-Paul Gaultier and Marc Jacobs have continued these gender-bending innovations, at the same time as being openly gay in their own lives.