INTERNATIONAL LIVES IN THE MODERN ERA

Maharaja of Chhatarpur 1866–1932

His Highness Maharaja Sir Vishwanath Singh Bahadur was the hereditary ruler of the princely state of Chhatarpur, now part of Madhya Pradesh in central India. He came to the throne in 1867, when he was just one year old, but did not actually rule until he reached adulthood and had received a British education. According to the elaborate protocol of colonial India, the maharaja was entitled to an eleven-gun salute and a return visit after he called on the viceroy. The maharaja married in 1884, but his wife died before she had children; his second wife gave birth to a son. E. M. Forster had met Chhatarpur on his first trip to India, in 1912–13, when he worked as an amanuensis for the maharaja of Dewas Senior, and it seems that Chhatarpur decided that he, too, would benefit from the services of an English secretary. Forster proposed J. R. Ackerley, a recent Cambridge graduate who was destined to become literary editor of the BBC’s magazine The Listener, as well as a popular author and well-known homosexual.

Ackerley wrote a memoir about his time in India. Called Hindoo Holiday, it was published to acclaim in 1932, and contains a vivid portrait of the maharaja and his court. Ackerley describes him as physically unprepossessing (saying that he looked like a Pekinese dog), but intellectually curious and personally endearing. Ackerley also discovered that the maharaja shared his homosexual proclivities, which he directed towards favourites in his retinue and, in a strictly homosocial way, towards Ackerley himself: ‘He wanted some one to love him … He wanted a friend. He wanted understanding, and sympathy, and philosophic comfort.’ He had a weakness for male beauty, surrounding himself with comely subalterns and searching out new acquaintances. ‘We were on our way to the village of Chetla,’ Ackerley recorded on one occasion, ‘where a fair was being held, and where also, His Highness told me, there was a very beautiful boy.’

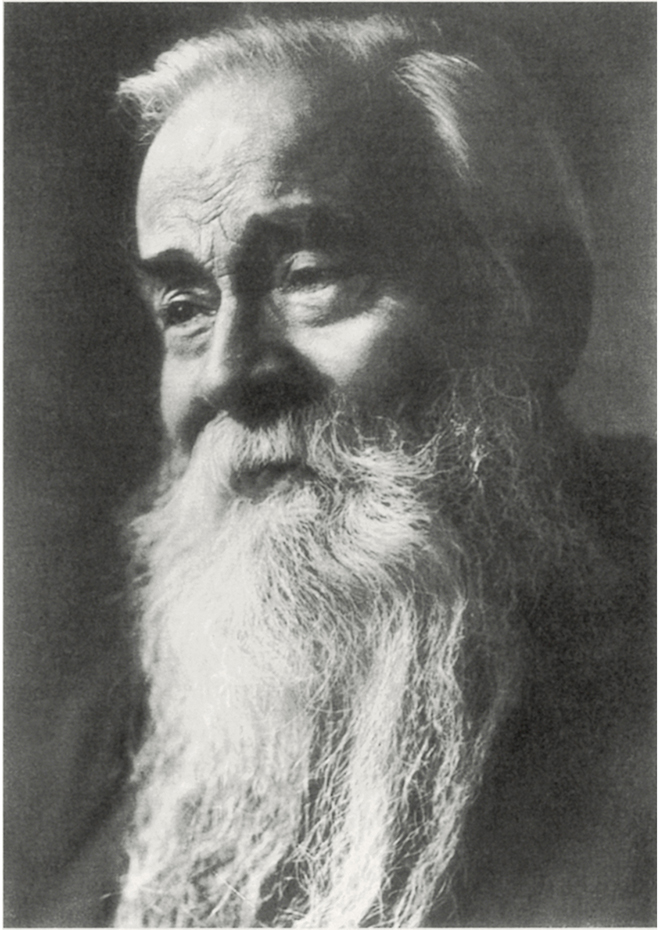

Postcard of the Maharaja of Chhatarpur, c. 1920 (Private collection)

The maharaja displayed a keen, if undisciplined, interest in the West, quizzing Ackerley on Darwin, Huxley and Spenser, on Roman history, Christianity and motor cars, and declaring that he envisaged his realm as ancient Greece. He even entertained fantasies about building a Greek villa (‘like the Parthenon’) and having his subjects don togas. The maharaja’s sexual tastes were also Greek. When Ackerley exclaimed that one of his young companions was a ‘bronze Ganymede’, the maharaja laughingly asked, ‘But where is the eagle?’, clearly seeing himself as Zeus swooping down on a fetching cupbearer. According to Ackerley’s biographer, Peter Parker, the publishers of Hindoo Holiday insisted on the excision of certain passages saying that the maharaja had been sodomized by a virile (if not altogether enthusiastic) valet, and that he had watched while the young man had sex with his wife. Indeed, the valet may have fathered the heir to the throne.

In Ackerley’s published account, which mischievously renames Chhatarpur as ‘Chhokrapur’, or ‘city of boys’, the maharaja happily chats about the beauty of his young servants with the Englishman, who is far from immune to their charms. Among the ruler’s extensive retinue were the ‘gods’: male adolescents who danced, played music and put on plays. (They seemed at times to perform other services as well.)

Ackerley noted that, although some of the retainers quietly mocked the maharaja’s proclivities, they were not above developing intimate connections with one another. Even those who were married were sometimes not averse to dalliances, and it is likely that men whose sexual urges were primarily homosexual nevertheless wished to marry and to father children (and that their families expected them to do so). Ackerley, too, entranced by the court’s graceful dhoti-clad men, initiated the occasional kiss and cuddle. ‘I must kiss somebody,’ the Englishman famously replied when the maharaja interrogated him about one of his overtures. His book describes how, during one embrace, a handsome fellow named Narayan promised Ackerley: ‘I will come and live with you for always.’

Around the time that Ackerley was in India, homosexuality was being discussed openly in the Indian press for the first time. The debate was sparked by the publication of Chocolate (1927), a collection of short stories that had appeared in a Calcutta newspaper in 1924 and were now being reissued as a book. Its author was Pandey Bechan Sharma (1900–1967), a novelist who wrote under the penname of ‘Ugra’. He was also a film-writer and a nationalist whom the British had jailed several times for subversion (nothing is known about his sexuality). Ugra declared that his intention in writing the stories was to combat homosexuality and to promote moral purity, yet they caused a controversy, both because they discussed a taboo subject and for their (discreet) depiction of men embracing and kissing.

Ugra’s characters are respected and educated men-about-town who generally are unapologetic about their desires, even if the stories often do not end happily. The tales recognize that the possibilities for homosexual love and sex are widespread in India, and Ugra quotes from traditional Urdu homoerotic verses to underscore the variety of forms that love can take. Oscar Wilde, whom Ugra compares to Krishna for his exaltation of pleasure, is also invoked. ‘Chocolate’ – a word that Ugra either borrowed from the local slang for homosexual sex or simply invented – implies nothing more than a sweet, delicious treat.

A British colonial statute of 1860 made homosexual acts illegal in India, and it remained on the books (even though it was seldom enforced) until 2009, when the Indian High Court declared the law unconstitutional. Three years earlier Manvendra Singh Gohil, who is the heir of the maharajas of Rajpipla, publicly came out as homosexual – the first Indian of royal descent to do so. He is involved in many charitable activities, having founded sexual health programmes and helped organize the first gay conference in India. (In 2009 he also appeared in a BBC reality show, in which, incognito, he had to pick up a man in a Brighton bar.) A growing body of scholarly and creative literature testifies to long-standing homoerotic traditions in Indian history, and it is clear that, eighty years after Ackerley’s visit to the Maharaja of Chhatarpur, a new gay culture is now emerging.

Historically, fantasy has always played a part in the attraction Europeans have felt for Asians. Heterosexual men have long had visions of delicate Oriental women clad in cheongsam or kimonos – images popularized by Pierre Loti’s book Madame Chrysanthème (1887), Puccini’s opera on the same theme, Madama Butterfly, and in accounts of the Shanghai girls of the 1930s.

Less glamorous reports revealed the bars and brothels of old Saigon or Manila, where sex was available for money, and with or without love. Homosexuals, too, fantasized about the ‘Far East’. Frederic Prokosch’s novel The Asiatics (1935), which takes the form of an imagined travelogue across Asia, from the Levant to the South China Seas, is studded with moments of homoeroticism; and Giovanni Comisso’s Gioco d’infanzia (‘Childhood Game’; 1965), based on the Italian’s adventures, follows a world-weary young European man as he immerses himself in the delights of Sri Lanka and China.

The boundaries between sexual fantasies and sexual realities have always been porous, and much literature (notably pornography) has drawn on stereotypes and dreams of desire. Lived experiences, too, become transformed, to the extent that memory and personal narratives often need to be viewed with scepticism.

The problem of veracity is dramatically illustrated by the story of Edmund Backhouse. He was born into a prominent Quaker family; his father was a banker and a baronet, and Edmund’s brother served as an admiral in the Royal Navy. Backhouse studied at the elite Winchester College, and then at Oxford. He never took a degree, however, having spent most of his university years dallying in aesthetic and homosexual circles. A nervous breakdown, heavy debts that threatened him with bankruptcy, and family disapproval of his lifestyle prompted him to leave the country for a year, but in 1898 he returned to Britain to spend a few months studying Chinese at Cambridge.

Shortly afterwards Backhouse went to Beijing, where he would live until his death forty-six years later, supported by an allowance from his father, whose title he inherited. After years drifting from job to job, Backhouse began to establish himself as a Sinologist. He co-authored a book on the Dowager Empress Cixi, translated works from Chinese into English, and regularly donated scrolls and other documents to the Bodleian Library. He enjoyed some esteem as a scholar and a philanthropist, and in 1913 the University of London offered him the chair in Chinese studies. Some, however, were unconvinced by his credentials and questioned the authenticity of the scrolls he sent to Oxford, and of the Chinese diary (rescued, he claimed, from the Boxer Rebellion) that served as the basis for China under the Empress Dowager.

Several decades after Backhouse’s death his biographer, Hugh Trevor-Roper, presented convincing evidence that Backhouse was a fraudster, that many of the sources on which he based his scholarship were unreliable, and that some of the scrolls he gave to the Bodleian were in fact fakes. Trevor-Roper’s own reputation was in question (he had authenticated a diary supposedly written by Hitler, which later turned out to be a forgery), but his judgment largely stands. As Robert Bickers, a historian of modern China, comments of Backhouse, ‘we know now that not a word he ever said or wrote can be trusted’.

Edmund Backhouse, c. 1935 (Bodleian Library, Oxford)

The two unpublished memoirs that particularly incensed Trevor-Roper detailed Backhouse’s sex life in Europe – where he claimed to have slept with Lord Alfred Douglas and other celebrities – and in China. Trevor-Roper declared that ‘both volumes are grossly, grotesquely, obsessively obscene. Backhouse presents himself as a compulsive pathological homosexual who found in China opportunities for indulgence which, in England … could be only dangerously and furtively enjoyed.’

One of the volumes – Décadence Mandchoue, written at the instigation of a Swiss doctor shortly before Backhouse’s death – is a remarkable work, not least for its overwrought style. It is peppered with passages in Chinese, French, Italian and other languages, classical quotations, and precious and antiquated turns of phrase. Even more surprising are Backhouse’s descriptions, in pornographic detail, of the gay life of imperial Beijing. Most extraordinary of all is his claim that he was the lover of Empress Cixi, and had sex with her nearly two hundred times. The idea that a middling Englishman such as Backhouse could have enjoyed access to the Forbidden City – much less become her sexual partner and confidant – beggars the imagination.

In writing about the homosexual milieu of the Middle Kingdom, Backhouse recounts his many and diverse experiences much in the way of a sex manual. He writes about male brothels, the versatile talents of actors and eunuchs, and the attractions of young men like his beloved ‘Cassia Flower’. Oral, anal and sadomasochistic sex; sex between two or many men; bestiality – all are described with little left to the imagination.

No one doubts Backhouse’s knowledge of China and of the Chinese language. A tradition of same-sex sexual relations certainly did exist in imperial China: actors became the catamites of noblemen and high officials, and in general male prostitution flourished. Not enough historical work has been done to verify or disprove specific facts mentioned in Backhouse’s accounts, however; some seem credible, while others are near outlandish. (An anecdote about Cixi visiting a homosexual brothel and ordering its denizens to perform for her, though wonderfully hilarious, strains belief.)

Backhouse’s work contains some clues about his intentions. He defends his chronicle as truthful, declaring that readers ‘shall not be astonished to learn that in this dissolute company of ancient debauchees and youthful profligates I was among the foremost in unbridled libertinage’, but adds that perhaps, in his case, it was ‘not wholly unaccompanied by literary allusion and poetical parallelism’. Backhouse further confesses that ‘This humble effort is only une chronique scandaleuse’, and refers to a British diplomat’s description of him as ‘brilliant in intellect, unbalanced in judgment and amoral in character’. Finally, he muses: ‘Is not perverse sexuality, especially such as mine, a form of insanity with lucid intervals …?’

Backhouse’s Swiss friend described him as ‘a distinguished looking old scholarly gentleman dressed in a shabby black, somewhat formal, suit who had a definite charm and spoke and behaved with exquisite slightly old-style politeness’. Looking back from the age of 70, Backhouse reminisced that ‘the sexual act, passive even more than active, afforded to me a ravishing pleasure: the intromission of Cassia’s highly militant organ instead of being a prod or a goad, connoted an exquisite, entrancing gratification, une sensation des plus exquises; like the first night in heaven’. The memory, real or fabricated, says something about Décadence Mandchoue and about Backhouse’s life. For an English baronet in war-torn China, implicated in suspect commercial schemes, occasionally rumoured to be a spy and accused of having stolen Chinese treasures, scribbling erotic memoirs provided a way to cock a snook at polite European and Asian mores. The pretence of truthfulness is part of the literary project behind his text, the naughty legacy of an old rake and poseur. The publication of Décadence Mandchoue more than half a century after his death represents the recovery of a pseudo-historical documentary on the sex life of imperial China – a divertissement that stands as a little gem of erotic literature.

When Festus Claudius McKay was born, Jamaica was a British colony, dominated by the sugar plantations that covered the whole island. His parents were farmers and had eleven children, of whom Claude was the youngest. At an early age McKay was sent to live with his eldest brother, who had managed to become a teacher, so that he could receive an education – an experience that opened up to him the world of letters.

A chance meeting with an Englishman at the carriage-maker’s where he was apprenticed introduced McKay to his future patron and mentor. Walter Jekyll was the son of an army captain; having studied at Harrow and Cambridge, he abandoned a vocation in the Anglican priesthood and studied singing in Milan. In the hope that the tropical climate would help relieve his asthma, Jekyll moved to Jamaica with his intimate friend Ernest Boyle in 1895 – also the year of the Oscar Wilde affair, which was perhaps not a coincidence. Among his other hobbies (he wrote a volume on music and a critique of Christianity, for instance), Jekyll developed an interest in the black peasantry and its culture, and published a collection of Jamaican folktales. McKay availed himself of Jekyll’s library, later recalling that Whitman, Carpenter and Wilde were among the authors they read and discussed. Jekyll encouraged the young Jamaican to write poetry in the local creole.

McKay’s first book of poems, Songs of Jamaica, appeared in 1912. That same year, he left the island, never to return. Jekyll had helped him to enrol as a student of agronomy at Booker T. Washington’s pioneering university for blacks, the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, but McKay was unhappy there and transferred to a public university in Kansas. Regretting his choice of career, he abandoned tertiary education without taking a degree and in 1914 moved to New York. While there, he worked at odd jobs, married a childhood sweetheart (though they broke up after a year) and began working as a journalist on a black socialist newspaper. According to his biographer, Wayne F. Cooper, McKay had brief passionate affairs with both men and women during this period, and throughout his life, but his orientation was predominantly homosexual. Various names have been circulated, but there is little evidence for who his partners were.

In 1919 McKay moved to England. He would spend most of the next fifteen years in Europe, with the exception of a long stay in Morocco. In London, he found employment with a left-wing workers’ newspaper that confirmed him in his socialist (and atheist) perspectives. Three years later he journeyed to Moscow to take part in the fourth congress of the Communist International. He also lived off and on in France for several years, in both Paris and the Midi. During his time in Europe, McKay published novels that count among the most significant in African-American literature: Home to Harlem (1928), Banjo (1929) and Banana Bottom (1933), the last of which he dedicated to Jekyll. The novels were eagerly received, although W. E. B. Dubois, the grand old man of the American black intellectual scene, disapproved strongly of Home to Harlem because of its blatant portrayal of sexual licence.

In 1934 McKay himself went ‘home’ to Harlem. Over the past fifteen years, New York had played host to the Harlem Renaissance – a cultural movement of African Americans and Caribbean migrants loosely connected in the ‘black metropolis’ (as one of McKay’s books described it). Segregation, disenfranchisement and poverty were the lot of most blacks in the United States, but Harlem provided a space for greater freedom and sociability, and encouraged the cultural expression of the ‘New Negro’ poets, essayists and journalists. At the jazz clubs, speakeasies, costume balls and ‘rent parties’ (private parties held to raise money for cash-strapped tenants), there was also an open attitude towards sexual expression. The first creative writings to have a black homosexual theme, by Richard Bruce Nugent, appeared in the mid-1920s, and a number of other authors linked to the Harlem Renaissance were gay or bisexual: Countee Cullen, Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, Alain Locke and McKay himself, as well as the sculptor Richmond Barthé and the blues singer Gladys Bentley. Whites like Carl Van Vechten, the author of the controversial Nigger Heaven (1926), also frequented Harlem to search for literary subjects – and sometimes homosexual pick-ups.

Although most of the black writers remained fairly discreet about their sexual leanings, the novels and jazz songs about Harlem often refer to homosexuality, either openly or in coded form. (The lyrics of ‘Sissy Man Blues’, ‘The Boy in the Boat’ and ‘Freakish Man Blues’ are noteworthy.) Homosocial relationships and homoeroticism feature in McKay’s writings in the context of his black characters’ energetic sexual appetites. The sex of the partners in his poems is generally unspecified – a curious, if perhaps intentional, omission that allows for varied interpretations. The influence of Edward Carpenter’s ideas on sexuality has been discerned in Home to Harlem, which contains an overtly gay minor character, a ‘pansy’ dancer, and a protagonist who, though nominally heterosexual, invites a ‘queer’ reading.

The theme of friendship between a masculine, working-class man and a gentle, intellectual and politically radical friend – already present in Home to Harlem – reappears in Banjo, a novel set in the docklands and slums of Marseille. As France’s major port, and the gateway to Africa and the colonies, in the inter-war years Marseille had a cosmopolitan population. Africans, West Indians and Arabs populate the book, whose title refers to the charismatic, sexually potent and affable longshoreman who is known for his banjo-playing as much as for his eating, drinking and womanizing. The narrator of the novel, who is manifestly based partly on McKay himself, is a young writer who pals around with the black denizens of the port but almost never shares their penchant for visiting brothels and enjoying flings with the women of the waterfront. His attachment to Banjo, however, is obvious – a brotherly bonding that has strongly erotic overtones.

McKay spent his last years in the United States, becoming an American citizen in 1940. Four years later, suffering from ill health, he converted to Roman Catholicism, and died from cancer in Chicago in 1948. His works had a great influence on later African-American writers, including the openly gay James Baldwin.

Claude McKay and Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Harlem, 1922 (George Granthan Bain Collection/Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

Sri Lanka – or Ceylon, as it was known in colonial times – was a serendipitous island for many foreign homosexuals. Edward Carpenter was among those enchanted with its tropical beauty and with the friendliness of its people, and a procession of later expatriates – Paul Bowles, Donald Friend, Arthur C. Clarke – settled there. Lionel Wendt was a Sri Lankan whose modernist photography erotically blends Western and Eastern imagery and allusions. He was also the leading figure in Colombo’s avant-garde cultural movement in the years before the Second World War.

Wendt was born into a wealthy Burgher family, of mixed Dutch and Sinhalese ancestry. He grew up immersed in European culture and literature, and had a particular fondness for Proust. Wendt’s father was a supreme court judge, a member of the colonial Legislative Council and a founder, in 1906, of the Amateur Photographic Society of Ceylon; his mother, a social worker, came from a family of civil servants. Ceylon was a British outpost, where it was normal for promising young men with private incomes, like Wendt, to travel to England for their education. In 1919 he arrived in London to study law, but also trained at the Royal Academy of Music and became an accomplished pianist. Having qualified as a barrister in 1924, he practised for only a short time before returning to Ceylon. Thereafter Wendt lived a comfortable life in Colombo, giving public recitals but increasingly turning to photography as a mode of expression. That he was homosexual was known to friends and associates, but he was discreet about his liaisons.

In the early 20th century Colombo hosted only a small avant-garde artistic circle. The dominant cultural influences were the ancestral religions of the island’s Buddhist and Hindu populations, as well as the starchier contributions of British colonialism. In the late 1920s a group of young figures, including Wendt, his friend the painter George Keyt and other mavericks attempted to stimulate Ceylon’s torpid cultural life and to introduce the more innovative Western styles of art, music and literature. They organized an exhibition of Cubist, Futurist and Post-Impressionist art in the early 1930s, which shocked traditionalists but drew praise from the poet Pablo Neruda, who at that time was Chile’s consul in Colombo and a friend of Wendt. Wendt himself gave piano concerts, playing pieces by modernist composers such as Debussy, Poulenc and Bartók to audiences little accustomed to the latest musical developments. He also became fascinated with cinema, and in 1934 narrated the film Song of Ceylon, an award-winning documentary made by Basil Wright and sponsored by the Ceylon Tea Propaganda Board. The film lyrically records the religious observances, landscapes and scenes of daily life in Ceylon, and often features slender young men dressed in lungis – images that reflect Wendt’s own photographs.

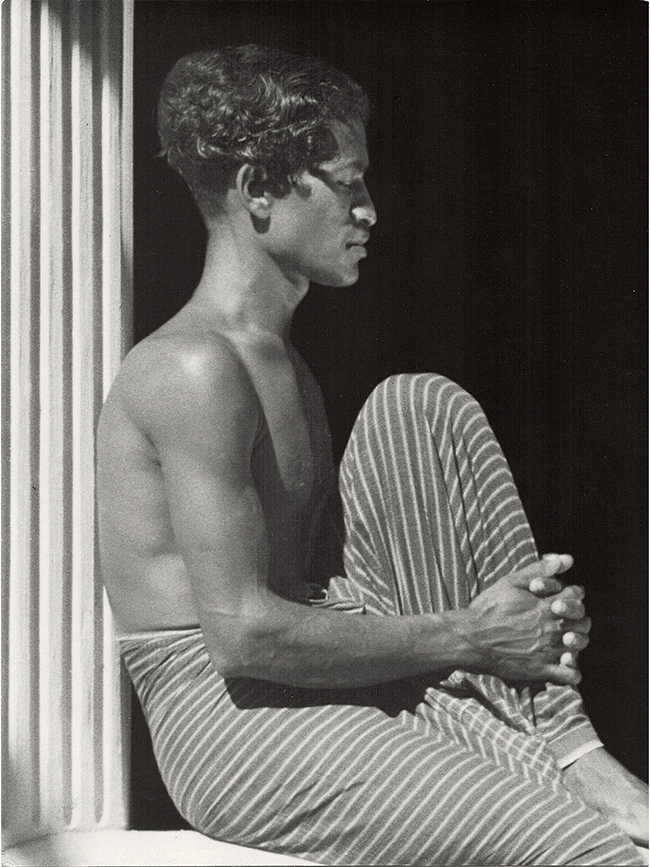

Lionel Wendt, Self-Portrait, undated (Lionel Wendt Memorial Fund, Colombo)

Lionel Wendt, Untitled, 1940 (Ton Peek Photography, Utrecht)

With photography, Wendt found his real métier. An exhibition of his works was held in London in 1938, and several made their way into magazines. Much influenced by the experiments undertaken in early 20th-century Europe, he adopted such techniques as multiple exposures and solarization. His cameras – a Rolleiflex and a Leica – captured a variety of subjects: landscape scenes, portraits of Sri Lankan notables and friends, and some very interesting surrealist images. A considerable number are homoerotic, however, and he is certainly one of the earliest non-European photographers to produce such a body of work.

Wendt’s photographs of this type document youthful Ceylonese going about daily life. Fit young workers climb trees for coconuts, wash at public fountains, tend houses or temples, towel off pet dogs or draw water from a well. Many viewers would not immediately see them as erotic, but a careful observer might note how Wendt dwells on the men’s physiques – the strong backs, powerful legs and buttocks of youths shimmying up coconut trees, for instance – which he emphasizes by means of subtle chiaroscuro lighting. Sometimes small details, such as the shimmering water streaming down the torso of one dark-skinned young bather, create particularly sensual motifs. Ceylon’s hot climate afforded many opportunities for shooting scantily dressed labourers, domestic servants, dancers, rickshaw-wallahs and boatmen, and his subjects appear in scenes of masculine sociability.

In both his plein-air and studio work – aesthetically posed and sexually charged figure studies, generally empty of all but a few props – Wendt places the statuesque bodies of young men centre stage. Some pictures focus insistently on buttocks or loincloth-clad groins. While most of the boys in Wendt’s softer, Pictorialist-style images are workers, one especially elegant nude, posed sipping tea, looks very middle class. Overtly sexual imagery is absent, although one boy, asleep on a couch, rests his left hand on his bare chest, stretching the other suggestively across his crotch. Pictures of naked women repeat some of the tropes and camera techniques, but Wendt returns again and again to the male body.

Several of Wendt’s more surrealist images vibrate with hints about his private life and desires. One features a comely man who seemingly offers himself to the viewer: lying on his back, with his arms stretched upwards, he is posed against cross-shaped ship masts in a series of multiple exposures. Wendt took the title, I Heard a Voice Wailing, from a poem by Christina Rossetti. Called ‘A Ballad of Boding’, the poem speaks of ships and dreaming and love; it begins: ‘There are sleeping dreams and waking dreams / What seems is not always as it seems.’ The hazy background in Wendt’s photograph is certainly oneiric; and the ship motif promises voyages of discovery (like Rossetti’s vessels, sailing to the East), but also the pain of departure and separation.

Another of Wendt’s images – a picture of the photographer’s desk – sums up his homosexual sensibility. For alongside his camera and ashtray are one of his photographs of a nude Ceylonese man, and a plaster-of-paris statue of a naked Greek god, the Apollo Belvedere. Here Wendt has set up a mise en scène of antiquity in the tropics: a classical gay icon in sculpture next to a modern photograph of a beautiful South Asian, set for the purposes of contemplation on an altar-like worktable. A mask and, on the wall, what appears to be a portrait of Wendt himself hint at meanings behind the images.

Lionel Wendt, Photograph of Desk, undated (Lionel Wendt Memorial Fund, Colombo)

Wendt died of a heart attack in 1944, at the relatively young age of 44. Although many of his negatives were destroyed after his death, a collection called simply Lionel Wendt’s Ceylon was published posthumously, in 1950. These pictures were again reproduced, along with further works, in a volume issued to mark the centenary of his birth. The Lionel Wendt Memorial Theatre and Art Gallery in Colombo perpetuate his memory.

Homosexual visitors to exotic parts often voyeuristically photographed the handsome men who caught their fancy. In Wendt’s work, however, viewers see the striking efforts of a ‘native’ photographer to combine allusions full of meaning for homosexuals with scenes drawn from the life around him. The afterword to Wendt’s centenary volume notes that he was someone ‘born and bred in a small topical island [who] could move easily and freely in the literary and artistic tradition of Europe’. Part of that tradition was homoerotic, and Ceylon provided a congenial environment for it to take root.

Except for a few rare traders and missionaries, the culture of Vietnam – its indigenous traditions, Buddhist religion and Confucian ethics – was for centuries little known to outsiders. Conquest by the French in the last decades of the 19th century added a layer of European culture, resisted and rejected by some, but assimilated by others. One who absorbed these foreign influences was Xuan Dieu.

Born in northern Vietnam in 1917, Xuan Dieu was the son of a teacher. He was educated at a colonial lycée and law faculty. In the 1930s he became a leader of the Tho Moi, or ‘New Poetry’, movement, whose works showed a familiarity with French writers and the ideas they espoused. The formalism of the old, Sinified schools of literature stressed the importance of mastering and imitating the Confucian classics, as well as the values of a corporatist and hierarchical society. By contrast, the New Poets adopted an individualistic, emotional and romantic outlook. A world-weary melancholy, wilful decadence and aestheticism marked the new modernist poets, much as it had their European counterparts several decades before.

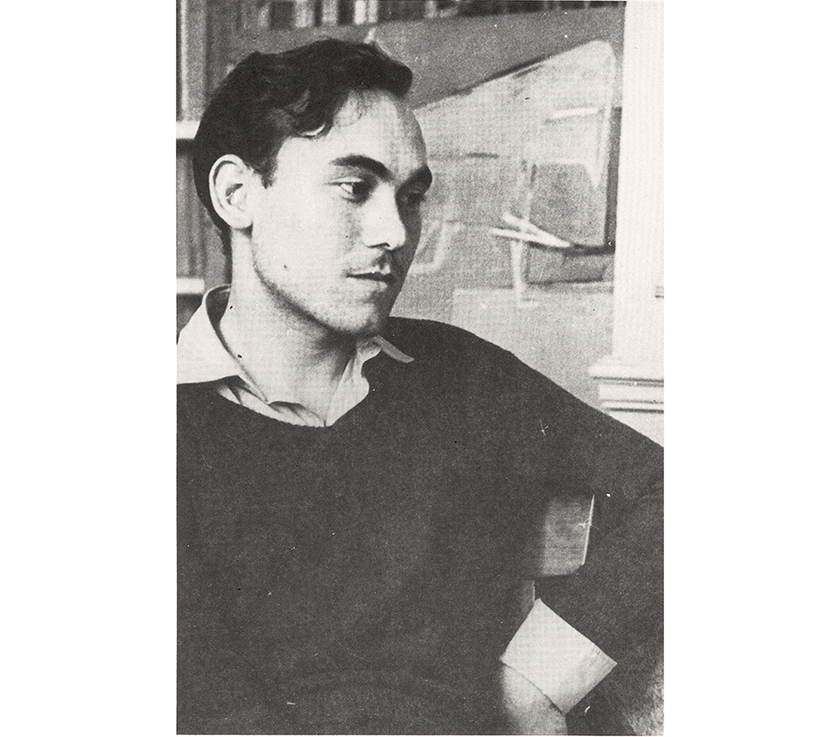

Xuan Dieu, c. 1950 (Private collection)

In an essay on poetry, Xuan Dieu wrote admiringly of the impact of French writers on his own work and on Vietnamese cultural life in general, for ‘the contact with French literature, especially French poetry, injected a flow of new blood into our society’. The classic French writers he encountered in his schooldays, especially Alphonse de Lamartine, taught him a new way of writing and thinking. Traditionalists in Vietnam thought in terms of ‘we’ – Confucianism linking together king and subjects, masters and students, fathers and children – but Xuan Dieu claimed that from the French moderns he had learned to use the word ‘I’ and to behave as an individual. Personal and poetic credos were thus combined. From Alfred de Musset he borrowed an emphasis on sentiment. With Baudelaire, ‘I took the full plunge into the heart of modern poetry’, while ‘Verlaine taught me about sadness … He showed me how to shape my sadness into beautiful poetic expressions.’ Verlaine was a particular inspiration, especially in Xuan Dieu’s love poetry, as can be seen from an open reference to Verlaine’s stormy relationship with Rimbaud in ‘Male Love’: ‘I miss Rimbaud and Verlaine / The two poets dazed by drinking / Intoxicated with exotic poetry, and devoted to friendship’.

Few of Xuan Dieu’s 400 poems have been translated into English. A selection of works from the 1930s rendered into English by Huynh Sanh Thong convey a pining desire for love, yet also the knowledge that love is transitory (a reflection of Buddhist views on the transitoriness of all life and sentiments) and often not quite sufficient. ‘You love me, but it’s still not enough,’ he admonishes one lover (‘You Must Say It’), and elsewhere laments, ‘Without fair warning, flowers bloom and droop: / love comes and goes at pleasure – who can tell?’ (from ‘Come On, Make Haste’). In another work (‘To Love’), he sighed: ‘To love is to die a little in the heart.’

Many years later, in the essay on French and Vietnamese poetry, Xuan Dieu quotes from one of his earlier verses, asking: ‘How can one explain love? / It doesn’t mean anything, a late afternoon / It invades my heart with softening sunlight / With light clouds, with gentle breeze.’ And he confided, enigmatically: ‘My entire being vibrates like the strings of a violin / While listening to the murmuring of what I have tried to hide.’

Although Xuan Dieu was briefly married, he did not sign the papers validating the union and probably never consummated it. His yearnings were for men. A memoir by a former lover, To Hoai, chronicled Xuan Dieu’s long-term partnership with another man: Huy Can, a fellow poet who was also a nationalist, a Marxist and, later, a high-ranking official in independent North Vietnam. Anti-colonial nationalist feeling was increasingly strong among the Vietnamese elite in the inter-war years, and emerged in a more militant form after the Second World War, when Ho Chi Minh led the struggle for independence. (France was ultimately defeated at Dien Bien Phu in 1954.)

Within this context Huy Can converted his lover to Marxist nationalism. Xuan Dieu joined the Viet Minh in 1944, took a job as the editor of a poetry magazine the following year, made radio broadcasts and gave speeches to rouse support for the nationalist cause. In 1946 he accompanied Ho to France for the political negotiations that failed to secure peaceful independence for Vietnam. Once he was fully engaged in politics, Xuan Dieu renounced his individualistic, romantic poetry and dedicated himself to the revolution.

Duing his campaigning, Xuan Dieu continued to be sexually active and had multiple partners. In 1952 he was subjected to a ‘rectification’ session by the Communist Party: comrades had criticized him for his ‘evil bourgeois thinking’, although he decided that it was his homosexuality that caused concern. He subsequently proved an ardent champion of Ho’s forces and orthodox ideology, and praised official values in the struggle for the liberation and unification of Vietnam. Many of his later poems are pieces of socialist agitprop. The new regime that followed independence expected loyal cadres to channel their desires to the greater good of nation-building. Lai Nguyen An and Alec Holcombe, both specialists in Vietnamese literature, suggest that there was a trade-off: the poet unquestioningly supported the government, which seemingly turned a blind eye to his homosexuality, and indeed provided a spacious house in Hanoi that he shared with Huy Can. For a time, Xuan Dieu’s half-sister lived there too, as Huy Can’s wife.

Despite having repudiated his earlier, individualistic poetry, in 1956 Xuan Dieu availed himself of a short period of greater political and cultural openness in Vietnam to publish an article on Walt Whitman, hinting at his empathy with the notion of comradely love. Some critics still regarded his writing as not sufficiently collectivist and made disobliging comments about his relationship with Huy Can. Nonetheless, several decades after his death the Vietnamese government continues to regard him as a hero: it posthumously awarded him a prestigious prize and named a Hanoi street in his honour.

Xuan Dieu’s works embody the intertwining of local and colonial influences, of traditional, modernist and revolutionary perspectives. ‘I am an explorer and an importer’, Xuan Dieu concluded – an example of migration between cultures.

Jean Sénac was a pied-noir (‘black-foot’): a European in colonial Algeria, which the French had conquered in 1830. The pied-noir population was made up of migrants from France, Italy, Malta and, as was the case with Sénac’s family, from Spain. His grandfather, a poor miner, had settled in the coastal region of Oran. Sénac grew up in very modest circumstances, raised by his mother, who worked as a cleaner, and by a stepfather; the identity of his biological father was unknown. At the start of the Second World War, when Sénac was an adolescent, France was occupied by Germany, and Algeria came under the control of the Vichy regime. After the war he fulfilled his obligatory military service and spent a period in a sanatorium, suffering from paratyphoid fever and pleurisy. On his recovery, in December 1948, he began to work for the French radio in Algeria.

Throughout the 1940s, when circumstances allowed, Sénac wrote poetry and moved in local artistic circles; and in 1947 he began a correspondence with the writer Albert Camus, a fellow Français d’Algérie who would become his friend and mentor. Sénac’s first collection of poetry was published in Paris, with a foreword by Camus, in 1954. That year also marked the beginning of the Algerian War of Independence, which would last until its fratricidal and bloody conclusion in 1962.

Jean Sénac, 1951 (Raimondo Biffi Collection)

Several themes marked Sénac’s life and work. In the background was always Algeria. Although he never learned Arabic or converted to Islam (few of the French did), he felt viscerally attached to the place. Algérianiste writers had talked about a new European race emerging from the various migrant populations that had put down roots in North African soil. They envisaged an easy (if separate) cohabitation with Muslim Algerians and Jews: a hybrid culture drawing on the legacy of the Romans and the Europeans (the Berber and Arabic heritage was seen to play a smaller role) and on the sun-drenched lifestyle of the Mediterranean. Sénac relished this existence, although he was never blind to what it cost the indigenous people and hoped for an enduring multicultural society in the place he always considered his patrie, his true home.

Homosexuality was a vital part of Sénac’s being. He had his first youthful sexual experiences in Algeria, and wrote evocatively in poetry and prose about his love affair with a Frenchman in the 1950s, and about his casual encounters with the Algerian Arabs he met in cinemas or cafés or at the beach. Finding sexual partners among young Algerians was never difficult, even if many engaged in same-sex relations only furtively. As he grew older Sénac wrote of these meetings, and of the sexual attraction he felt for Algerians, with increasing confidence and in greater detail. In 1957, while on a trip to France, he met a young Parisian named Jacques Miel; they had a brief sexual liaison, and Miel eventually became the writer’s closest friend, and his adopted son and heir.

Sénac’s experimental poetry is often elliptical and hermetic. He created a new form of poetry: called ‘corpoème’, it was intended as a metaphorical melding of Sénac’s sexual interaction with the body of a lover and his literary reaction to such encounters. The images leave no doubt about his sexual desires and experiences. He explains how social mores, sexual hunger and poverty created possibilities for encounters, ‘the handsomest boy taken / for the price of a film ticket’. He recalls moments of sensual pleasure: ‘just the memory of such adolescents / provoked a ferocious orgasm’. In a poem entitled ‘La Course’ (1967), he speaks of thwarted love and of raw, frustrated lust: ‘You carry on and on about love. But I understand / only the pain in the balls that have only a mirror / in which to empty themselves’; reciting a litany of Arabic names, he called on the men to bugger him. But he also conjured up beautiful images of the desert, the sea and his partners. In a homage to a lover, called ‘Brahim the Generous’ (1966), he writes: ‘You gave me back light and peace / The curve in the steep path / The science of the well and the bashfulness of the water … / This dessicated heart you have also made your domain.’ In poems about Abu Nuwas, Rimbaud, Wilde and Lorca, he invokes other homosexual writers and sets out his hopes for sexual emancipation.

For the other major theme of Sénac’s life was political engagement. He was an early supporter of the Algerian nationalists who waged an eight-year war of independence. Although he never joined the National Liberation Front, and his activities during the war, which he spent in France, remain somewhat clouded, his writings called on the French to grant independence to Algeria. He begged the pieds-noirs to remain in the country and urged the construction of a new, revolutionary society in which Europeans, Arabs and other populations would each have their proper place. In 1962, as a million pieds-noirs fled the newly independent Algeria, Sénac returned, full of hope. He resumed his radio broadcasting, helped establish literary journals, wrote literary and art criticism and poetry, and became one of the major figures of French-language cultural life in Algiers. Sénac’s writings (including some agitprop poems) lauded the ‘citizens of beauty’ and the new order, and they championed the heroes and causes of the time – Che Guevara and Ho Chi Minh, resistance to capitalism and imperialism, love and sex.

In the mid-1960s Sénac fell out of step with the Algerian government, which was becoming more dictatorial and militaristic, and less congenial to non-Arabs such as himself. As he had once criticized the old colonial system, now he chastised the new regime for its ideological rigidities, failure to attack poverty, lack of development and curtailment of freedom. His poetry, too – with its ever more vivid accounts of homosexual desire – hardly found favour in this prudish climate. Finally dismissed from his post at the radio station in 1972, Sénac sank into poverty. He moved from a beachside suburb to a squalid inner-city basement, and his writings expressed a gloom bordering on despair. In August 1973 he was murdered; some suspected political involvement, but it is more likely that he was killed by a disgruntled hustler or a former sexual partner.

M. Butterfly, by David Henry Hwang, won the 1988 Tony Award for best play on Broadway, and five years later became a popular movie. It recounted the strange relationship between a French diplomat and a male singer in the Beijing Opera who convinced him that he was a woman. They had a child together, before both were convicted in France for working as Chinese spies. Hwang based his work on a real-life case that is perhaps even more complex than its theatrical counterpart.

Shi Pei Pu, who died in 2009, was born in Shandong, China, in 1938. He moved to Beijing and worked successfully as an actor and singer, then became a writer and teacher of Chinese to diplomats and their families. In 1964, at a Christmas party for diplomats posted to the Chinese capital, Shi met Bernard Boursicot, who had recently arrived to work at France’s newly established embassy. Boursicot, who came from a working-class family in Brittany and had neither the bourgeois background nor the university degrees generally held by members of the foreign service, was employed under contract as an accountant. Shi, who spoke French well, told him that he was the son of an academic and had studied literature at the University of Kunming; his father had died, and he lived with his mother. He had two elder sisters, one a table-tennis champion, and the other married to a painter.

Boursicot and Shi became close friends – an intimacy unusual in Maoist China – and Boursicot believed Shi’s confidential revelation that he was a woman. Shi (who was later guarded on the point) seems to have convinced him that his parents, who already had two daughters, had decided when he was born to raise him as a boy. Soon after Shi’s confession, the two started on a sexual relationship; their encounters were brief and fumbling, however, and Shi – who insisted on darkness – refused to appear in the nude. Their relationship continued for a year, until Boursicot resigned from his position and left China.

The details surrounding Shi’s life over the next few years, during which China experienced the terrors of the Cultural Revolution, remain unknown. Four years after he had left, Boursicot returned to China, to work once more at the French embassy. He located Shi, and they resumed their sexual relationship (mainly, it seems, involving masturbation and oral intercourse). To the authorities, Boursicot justified his visits to Shi’s house as a chance to study Chinese language and Maoist thought. When another person arrived at Shi’s home to tutor Boursicot in revolutionary philosophy, Boursicot agreed to engage in espionage in order to facilitate his contacts with his lover. Shi later claimed that he was absent when Boursicot provided documents and information to the contact, who clearly had been planted by the government. Between 1970 and 1972 Boursicot handed over scores of confidential diplomatic reports, but it seems unlikely that he would have had access to anything other than low-grade intelligence.

In 1972 Boursicot again left China. He returned briefly the following year, as a tourist, when Shi introduced him to their ‘son’. Once he was back in France, he began a sexual relationship with Thierry Toulet, and the two moved in together. Boursicot’s foreign service took him to the United States, but in 1977 he applied for posting to France’s tiny embassy in Mongolia. Since one of his duties was to courier a diplomatic pouch, Boursicot regularly travelled from Ulan Bator to Beijing, where he met up with Shi and once more began low-level spying. At the end of his term in Mongolia, in 1979, he returned to Paris, where he arranged for Shi and their ‘son’, Shi Du Du (also known as Betrand) to migrate. They arrived in 1982 and settled in with Boursicot and Toulet. The following year, agents from the French security services arrested Boursicot and Shi.

The prosecutors charged both men with espionage. Amid great publicity, the judges convicted them, sentencing each to six years in prison. In the event they were freed after less than a year. When prison doctors revealed that Shi – who was still claiming to be a woman, despite his men’s clothes – was in fact a man, Boursicot tried to commit suicide in his cell. Upon their release, they went their separate ways, Shi working as a performer and raising Shi Du Du, and Boursicot living quietly with his partner. When Shi died, Boursicot commented that he had been so taken in by Shi that he could feel no sadness at his passing. He cut a pathetic figure, gullible and credulous almost beyond belief, and continued to insist that he had believed Shi to be a woman. Perhaps he was a victim of his own Orientalist fantasies, as he is portrayed in Hwang’s play.

Shi Pei Pu in the role of a mandarin, 1962 (PA Photos)

Understanding Shi’s motivations is difficult. Did homosexual feelings propel the Chinese provincial boy towards the opera, where there was a tradition of actors and singers serving as catamites for patrons? Was he really in love with Boursicot, as he claimed? Did he never actually pretend to be a woman, but instead only aim to satisfy Boursicot in female guise (as he also maintained); or was he exceptionally talented at keeping his genitalia out of Boursicot’s reach and arguing that his diminutive breasts were the result of hormone treatment? Did he simply see the seduction of the Frenchman as an avenue for social advancement – the small luxuries a diplomat could provide and, ultimately, refuge in France? How could he manage to keep up the pretence and duplicity so well? (Shi’s ‘son’, it transpired, was purchased from an impoverished Uighur family.) What form did Shi’s life take without Boursicot, and how much of his own story was a tall tale? How deeply was he implicated in the espionage, and what were his relations with the Chinese authorities? How did he view the ménage à trois with his ‘husband’ and Toulet in Paris?

Europeans’ infatuation for Asians has been a trope of history and culture since the first encounters between West and East. Some contacts, such as that between Butterfly and Captain Pinkerton in Puccini’s opera (itself based on a real liaison between a British officer and a Japanese woman), were doomed. Most, inevitably, came up against questions of cultural expectations, stereotypes and a measure of fantasy. Literary critics commenting on Hwang’s play have focused on its issues of gender, difference and identity. The real-life story, too, makes one wonder about the unfathomable depths of human desire and the extraordinary situations it can produce, the vague boundaries between reality and fantasy, and the muddled intersection of private and public life.

Born into grinding poverty in rural Cuba – a destitution so extreme that hunger forced him and other children to eat soil – Reinaldo Arenas was raised by his kindly mother. He never knew his father. In his autobiography, Antes que anochezca (‘Before Night Falls’; 1992), he recounts his pubescent sexual initiation through intercourse with farmyard animals (common behaviour for young men in the countryside, he affirms) and erotic play with classmates. He evokes provincial Cuba’s atmosphere of violent machismo, but also the erotic bonding that occurred between youths.

Like many poor Cubans, Arenas supported the rebellion led by Fidel Castro that overthrew Fulgencio Batista’s corrupt government in 1958. Arenas benefited from the changes it brought about, and in 1961 won a scholarship to train as an agricultural accountant in Havana, later studying philosophy and literature at the city’s university. The 1960s also offered ample opportunities for sex. Men cruised in parks and on the beach; school and university residences were venues for sexual encounters; and army recruits were always ready to provide sexual services. The predominant ethos was that a man who played the active role in intercourse did not compromise his masculinity. The tropical climate, Arenas said, stimulated eroticism, and close physical contact with other men on crowded buses and in shared dormitories, as well as outdoors, made contacts easy. Arenas dived happily into homosexual life. He had versatile sexual tastes and a huge sexual appetite: he calculated, perhaps implausibly but still impressively, that by 1968, when he was 25 years old, he had had sex with 5,000 men; ‘I was neither monogamous nor selective,’ he wrote. He also fell in love and had several extended relationships.

During this time Arenas made the acquaintance of two of Cuba’s leading writers, both of them homosexual: José Lezama Lima and Virgilio Piñera. They both treated homosexual themes more or less openly in their works, and in Havana actively pursued their sexual interests. Their mentorship helped Arenas launch his writing career, and Lezama’s argument that beauty subverted dictatorship would provide moral support for Arenas in years to come.

In 1964 Arenas gained coveted, if poorly paid, employment at the National Library. Several years later his first novels, in manuscript form, won awards in literary contests. However, Arenas’ literary style – which did not conform to the precepts of socialist realism and was said to lack heroic and morally sound characters – offended the Cuban political authorities. ‘Ideological deviation’, his writings’ failure to fit into a revolutionary mould and the inclusion of homosexual figures brought him under suspicion. The early texts were (illegally) spirited out of the country and published to acclaim overseas. For Arenas, writing and sex went hand-in-hand: he declared that he could never be creative if he abstained. Yet his sexual exploits and increasingly dissident opinions were evidently provoking hostility.

From the 1960s onwards Castro’s triumphant revolutionaries had attempted to combat prostitution and homosexuality, and to reform those it considered social misfits through forced labour. In 1965 – when the gay American poet Allen Ginsberg was expelled from Cuba for repeating a rumour that Fidel Castro’s brother, Raúl, was gay, and adding that Che Guevara was cute – Castro declared that homosexuals were not oppressed, but that they could not be true revolutionaries or real Communist militants. By the early 1970s the campaign against homosexuals had gathered strength. Gay men were arrested, interrogated, tortured and imprisoned by the secret police; they were also accused of the crime of being counter-revolutionary. This crackdown was part of the Castro dictatorship’s general persecution of intellectuals, Christians and anyone who failed to support the regime. Along with other writers, Arenas was sent for a period to a forced labour camp on a sugar plantation.

Arenas’ homosexual activities, although hardly secret, were reported by informers (who included erstwhile friends and even an aunt), and in 1973 he was arrested. His autobiography recounts the horrific treatment he received, including six months of imprisonment before trial on charges of having had sex with minors. The two young men brought to testify against him denied the charges, resulting in a mistrial, but the judge nonetheless sentenced Arenas to two years’ incarceration in a hellish jail, where he several times tried to commit suicide. Under duress, he signed a confession admitting that he had sent his writings out of the country. In the meantime, police destroyed many of his remaining manuscripts. An international campaign for his release publicized the case but had little immediate effect.

Arenas was freed in 1976 but found it difficult to get a job, and there was still no possibility of publishing his works in Cuba. Having abstained while he was in prison – despite the opportunities it afforded – he resumed his sex life. Much saddened by the deaths of a beloved grandmother, and of Lezama and Piñera, he tried, daringly and unsuccessfully, to flee Castro’s rule by crossing an alligator- and mine-infested swamp to swim to the American military base at Guantánamo. Seeing little future in Cuba, in 1980 he managed to join the 135,000 individuals who left the island during the ‘Mariel exodus’, whose stated aim was to rid the country of criminals, the insane and perverts.

Arenas landed in Miami. Finding the city’s conservative and unintellectual Cuban expatriate community unwelcoming, he decided to move to New York. Although he judged America to be soulless, New York proved stimulating, and he enjoyed the opportunity it gave him to write freely. He completed or rewrote half a dozen novels, established a literary magazine, arranged for his mother to visit for several months, and had ‘memorable adventures with the most fabulous black men’ in Manhattan. Like many gay men in the 1980s, he contracted HIV; despite periods of debilitating illness and hospitalization, he finished a five-volume sequence of novels that he considered his life’s work. In 1990, depressed at his physical condition and inability to write, he took his own life, leaving behind an autobiography and a farewell note encouraging resistance to the Castro government; ‘Cuba will be free. I already am,’ he had written.

His widely translated novels, and the film adaptation of his autobiography released in 2000, have made Arenas the most famous Latin American homosexual of his generation. He was also one of the most forthright of authors in discussing his prolific sexual adventures. A mixture of machismo, Catholicism and conservative attitudes towards sexuality and the family have long characterized South American culture; they have also shaped the vibrant gay cultures of places such as Mexico City, Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro and Havana, whether clandestine or public.

Old attitudes, at least in some countries, have been changing rapidly: in Argentina, for example, same-sex marriage has been legal since July 2010. In Cuba, despite some modest changes, laws incriminating homosexual activities remain in force. The production in 1993 of an overtly gay film, Fresa y chocolate (‘Strawberry and Chocolate’) – which tells the story of an artist’s obsession with a handsome young Marxist student, who is nominally straight, and his eventual decision to flee the country – was seen as indicative of greater tolerance. In 2010 Castro conceded that his government’s treatment of homosexuals had been a ‘grave injustice’. The foreign press continues to report occasional crackdowns on Havana’s lively gay nightlife, however.