This moment yearning and thoughtful, sitting alone,

It seems to me there are other men in other lands, yearning and thoughtful;

It seems to me I can look over and behold them, in Germany, Italy, France, Spain –

Or far, far away, in China, or in Russia or India – talking other dialects;

And it seems to me if I could know those men, I should become attached to them, as I do to men in my own lands;

O I know we should be brethren and lovers,

I know I should be happy with them.

– Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass (1891)

The sex lives of celebrities (and the less famous) always excite the curiosity of others, as the tittle-tattle of gossip magazines, eager to recount the liaisons, the peccadilloes and the romances of film stars, sports heroes and politicians, amply testifies. Accounts provide an extra frisson when bedroom behaviour is tinged with something unusual, and the inside stories move to the front page when there is a whiff of scandal.

More serious writers, however, long shied away from peering into the secret chambers of the lives of public figures, even in the light of Freudian and other psychological theories that underlined the importance of sexuality. Many weighty and otherwise comprehensive biographies, though they might dwell on love and marriage, avoided sex. In some cases, intimate details found no place at all in a biography, being seen as largely irrelevant to the ideas and public activities of the subject. Some writers went to great lengths to deny sexual improprieties, convinced that such conduct would compromise their subject’s achievements, or that discussion of the messy business of sex would sully their own scholarship.

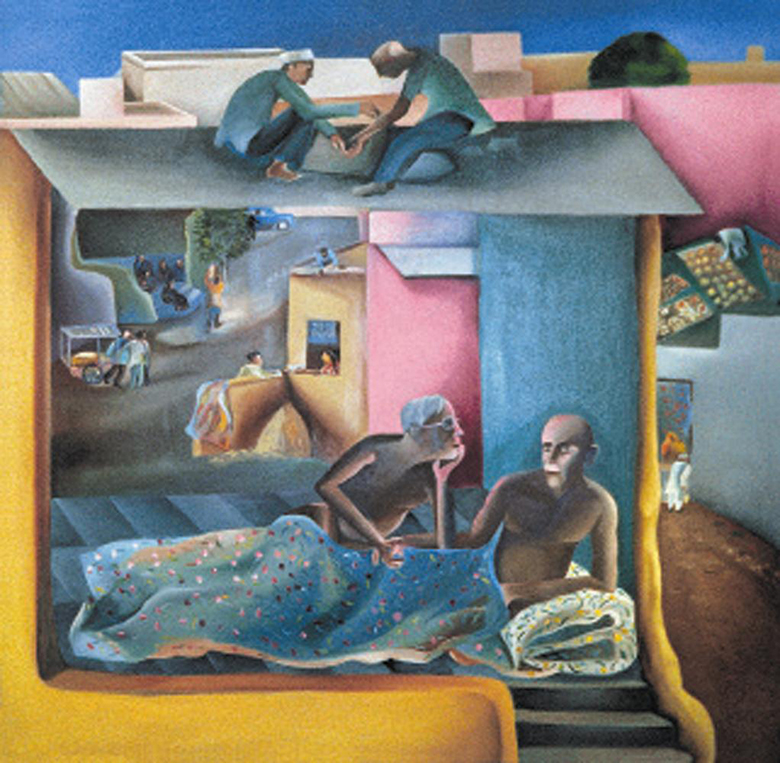

Bhupen Khakhar, My Dear Friend, 1983 (Private collection/Courtesy Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai)

More recently, the situation has changed. Women’s liberation and gay liberation argued that private life has a public side. ‘Gay pride’ mandated an open and proud affirmation of sexual orientation, and those who proved too reticent to admit their homosexuality were occasionally outed. Changing laws (at least in the Western world) made it possible for those whose sexual behaviour had previously been criminal to proclaim their desires and practices without fear of arrest, while AIDS made it difficult for those who fell ill to hide what society, notwithstanding the change in the law, often considered reprobate behaviour. The new academic fields of gender history and the history of sexuality underscored the significance of sex, in its manifold variations, in individual lives and in the collective life of different societies. Queer theory revealed the mutations and ambiguities of sexual identities, and promoted new readings of canonical and obscure texts and images. A consumerist obsession with sexual satisfaction – from pornographic and dating websites to the popular use of medications to enhance sexual performance – made sex an omnipresent theme in the media.

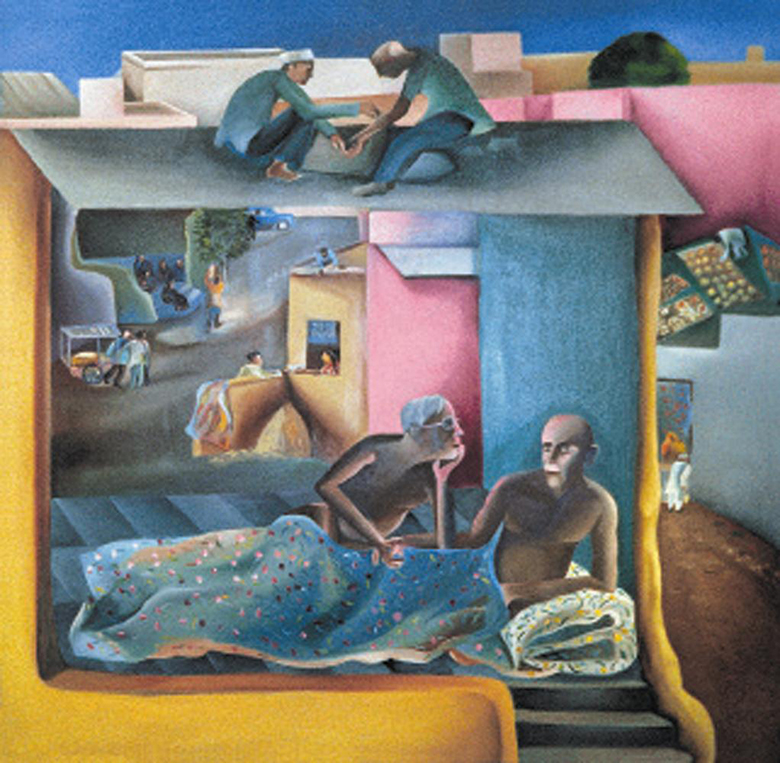

Dante and Virgil meet the sodomites, a manuscript illustration from Dante’s Inferno, c. 1345 (Musée Condé, Chantilly)

Sex – emotions and behaviour – does not provide the key to everyone’s life, but for most people it does form a central part of their sense of their place in the world and their interactions with others. Sex is never entirely a private matter. What individuals feel and don’t feel, do and don’t do, reflects their acceptance or rejection of social conventions: codes determined by religion, law, medicine, the media, and other standards of authority and opinion. Social and cultural expectations surrounding chastity, virginity, childbearing, monogamy and promiscuity, and ‘normal’ or ‘abnormal’ sexual acts influence an individual’s expression of his or her sexual desires. And, depending on time and place, the expression of certain desires may be celebrated or condemned.

The figures in this volume illustrate the ways in which those who felt an attraction to those of the same sex lived out their desires across time and around the world. Its purpose is not to offer a compendium of the lives of the ‘greatest gays’, nor to provide an encylopedic survey of the different sexual types identified by historians, anthropologists and other specialists. It represents, rather, a richly diverse congregation of figures, whose lives point up the different personal and social experiences of homosexuality through the ages. Some individuals are well known, some less well known, and none is still living. A particular effort has been made to embrace lives from outside Europe: an Arabic painter; a Sri Lankan and a Japanese photographer; a South African activist; a Jamaican novelist; a Vietnamese poet. Other figures – a nun, a priest, a military officer, a criminal – were chosen to show homosexual people in a variety of professional callings. Viewed together, their stories uncover the fashions in which sexual diversity has been expressed, and the connections between private lives and public life – between individuals and their specific historical and cultural environments.

For convenience, the terms ‘same-sex’ and ‘homosexual’ are used throughout, but this does not imply an essentialist approach. Indeed, the opposite is true: the lives reveal a great variety of individual and social attitudes towards ‘homosexuality’: paiderastia in ancient Greece; spiritual friendship in the works of the medieval monk Aelred, and the Neoplatonic, humanistic friendship lauded by Montaigne; the ambisexuality of Renaissance figures such as Michelangelo; the women-centred relationships of Rosa Bonheur; and on to Magnus Hirschfeld’s idea of a ‘third sex’, the out-and-proud gay liberation view of Guy Hocquenghem, and so on. The book takes a broad view of experience, without any attempt to find the stains on the sheets or to out any individual. Sexual orientation here is seen as emotional as well as physical – a question of intimate affinities, not just fornication; of love as well as lust.

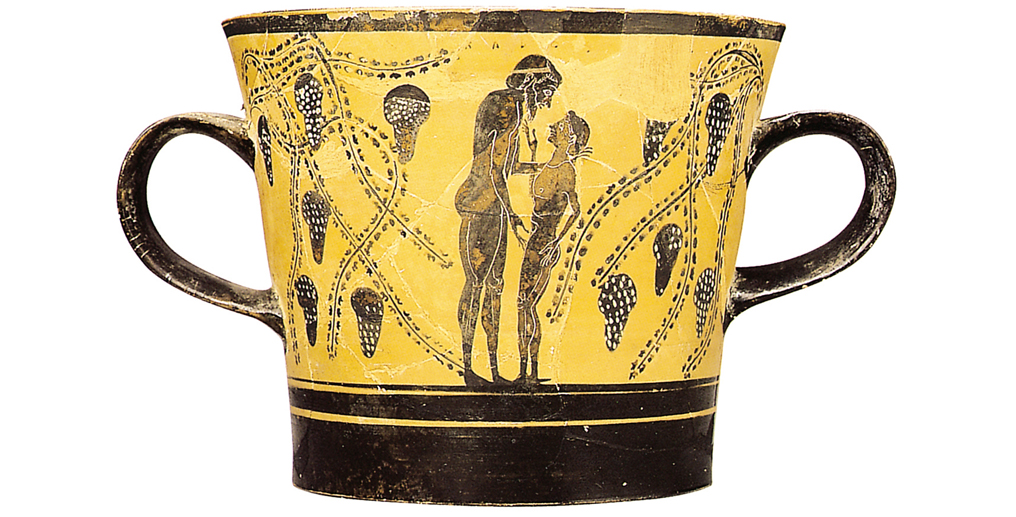

Attic black-figure cup showing an older man courting a youth, c. 520 BCE (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Several common themes emerge. Close friendship between men, and between women, has often been extolled – in Greek philosophy, Christian humanist treatises, medieval Arabic poetry, and tales of Chinese emperors and Japanese samurai – with a moving boundary between emotional and physical intimacy. Yet men and women with blatantly ‘contrary’ urges have often battled social censure, from sodomites burned at the stake in medieval Europe to homosexuals harassed by journalists and policemen in McCarthyite America. Despite taboos and interdictions, men who desired other men and women who desired other women, sometimes in the most inhospitable environments, have found spaces in which to pursue partners in love and lust – even in Hitlerite Berlin, gays and lesbians managed to make contact.

Particular images of the sexually dissident – such as the mannish woman or the effeminate man – circulated in different cultures, as did idealized models of the sexually desirable, notably the strong and independent woman typified by Radclyffe Hall or Annemarie Schwarzenbach, and the type of beautiful and muscular young man portrayed by Eugène Jansson. Historical antecedents of ‘gay’ love from antiquity were passed down, and homosexual men and lesbians (especially before gay liberation) would trace a family tree to the classical civilizations of Europe – allusions that can clearly be seen in the photographs of Wilhelm von Gloeden and in the novels of E. M. Forster. Similarly, in China Chen Weisong referred to the love stories of an ancient emperor and his partner, celebrating a shared culture handed down over the centuries. Ideas spread around the world as well: the photographs of Lionel Wendt, made in Sri Lanka, and of the Japanese Tamotsu Yato, for instance, draw on Western classical and Christian imagery as well as that of Asian cultures.

‘The Ladies of Llangollen’ as depicted on a porcelain tea bowl, c. 1840 (Private collection)

It is also notable how men and women often sought sexual solace in places far from home, migrating from small towns to big cities, and living for periods in seductive sites from the Mediterranean to distant colonial outposts. Wherever they went, they tried to settle down: consider the cosy domestic arrangements of the Irish-born ‘Ladies of Llangollen’ in Wales, and of Edward Carpenter and his comradely friends in England, and the succession of residences set up by Donald Friend in Australia, Italy, Ceylon and Bali. In this way they became part of wider national and international cultures: cultures of companionship and ‘marriage’, of travel and pilgrimage, of wild nightlife and uninhibited passion.

As well as offering an opportunity to recollect lived experiences, then, this gallery of portraits also traces a changing landscape of social mores, cultural contexts and political constraints: it reveals gay lives lived in history.