Gardening for food is brilliant because there are so many plants to grow, so many ways to improve the soil and make them grow better, and so much opportunity to enjoy the rewards. Every season I enjoy the challenge of new plants or varieties or ways of doing things. Success is sometimes elusive, although one is constantly learning, and it really is exciting when a new idea comes to fruition. But before that, some things need consideration when making your choice of what to grow.

How much experience do you have?

If you are a beginner, start with quicker and easier vegetables such as salads and spinach – as long as you are on top of slugs – and avoid demanding plants such as aubergines and celeriac.

How big is your growing space?

Some plants grow huge in just a few months and can take up large parts of a growing area, depriving their neighbours of light and moisture. Avoid these if your growing area is small.

How much time do you have?

Things will go best if you grow plants that suit your ability to look after them: for instance, salads and courgettes need constant attention compared with beetroot and purple sprouting broccoli.

Some examples to help you choose

For all of us, especially the beginner, nothing is more heartening than healthy growth and a worthwhile harvest. So I encourage you, initially, to grow what will grow most easily in your outdoor climate. For beginners in Britain, there is huge scope for rapid and interesting harvests of salads, because the time from sowing to picking is often less than two months, and many different plants are suitable. Some salad plants will then crop for two or three months, and many leaves can be gathered from relatively small areas, so I warmly recommend a close look at Chapter 9. Remember how much time is required for picking, making it worthwhile to have your salads as near to the kitchen as possible, possibly in a large pot outside the door.

If you have the space, a tasty and easy crop is new potatoes. They grow fast and reliably, and are out of the ground before their main disease, a fungus called blight that withers all the leaves, is even around. Potato plants are among the largest and quickest of all the root crops because they grow from old potatoes or tubers, which have enough food resources to propel young plants into rapid growth. Compare that to carrots – slowly growing from tiny seeds, which take an age to create enough root and leaf to make worthwhile growth – and parsnips, which take an age to even germinate.

Another space-hungry plant that is not too difficult is courgette, and it illustrates a highly important aspect of vegetable growing. How regularly can you be in the garden? Courgettes need picking every day, or two at the most, before they turn into small tender marrows and then, surprisingly rapidly, into large hard-skinned marrows. You may be caught out by the amount of time required for picking and dealing with your harvests, as one courgette plant can yield about 60 fruits between July and October. There is more work in harvesting and dealing with its output than in growing the plant.

Similarly, runner and French beans need frequent picking. The bean pods do not just develop and wait for us to gather them: they pass quickly through the tender pod stage on their way to becoming a tougher ripening pod that contains maturing seeds. It is such a pity that summer holidays occur when the garden is bursting with beans and other produce – another thing to bear in mind when you are planning.

The allium family is friendly in this respect: leeks, garlic and onions all grow slowly but steadily, and one harvest of garlic and onions, well stored, will afford many months of meals. Then once they are picked, there is still time for another crop of late salad or French beans or oriental greens. Familiarise yourself a little with all the possibilities so as to make the choices best suited to you and your family’s tastes.

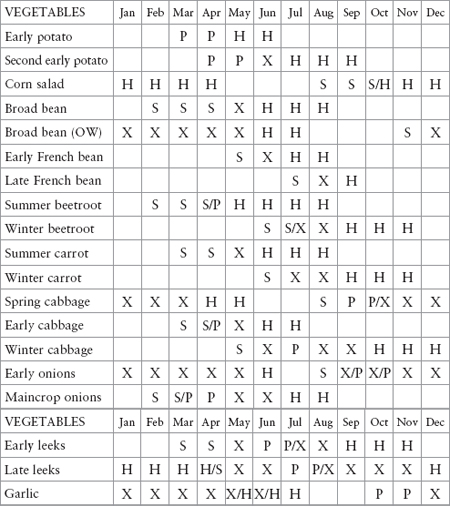

Successional cropping (see Plate 38)

Keeping the ground full of something growing at all times is highly worthwhile.

• First, there is more to eat.

• Second, the soil is more often covered by leaves, helping to conserve moisture and to protect from heavy rain.

• Third, there is less room for weeds, which are shaded out by growing crops.

• Fourth, the plot or bed is more beautiful.

One way to achieve a succession is by ongoing propagation of sturdy plants, preferably in a greenhouse. Work out when crops will finish and have another plant ready to fill the space. Most salads, beetroot, French beans, spinach, kale, fennel, kohlrabi and other vegetables are around for only half a season, giving lots of interesting combinations to play with. Look at the table below to pick out a few. Apart from corn salad (lamb's lettuce), salads are not included in this table because there are simply too many possibilities, arising from their great number and rapid growth. So they can often be slotted in before or after other vegetables.

Combinations for succession

Match up any last ‘H’ with a first ‘S’ or ‘P’ to see what vegetables can succeed each other. Even more combinations are made possible by doing the ‘S’ part in a greenhouse so you can follow ‘H’ with ‘X’.

S = sow

P = plant modules, tubers or sets

X = growing vegetable

H = main harvest

OW = overwintered

Rotation can be made into a frighteningly complex subject – indeed it often is. It simply means moving vegetables around the garden in succession, rather than growing the same ones in the same place every year, to avoid a build-up of pests and diseases.

A four-fold rotation of roots, brassicas, potatoes and miscellaneous vegetables used to be commonly recommended. The difficulty with this, and indeed with any strict rules, is that it tends to divide the vegetable plot into rigidly defined areas, making it necessary to grow fixed amounts of certain crops every year.

I recommend instead that you keep an awareness or a plan of what has grown where, aiming to avoid repeat cropping for as long as possible. This may mean a gap of only two years, and some people manage to grow vegetables such as runner beans in the same place every year. A short rotation is definitely helped by not digging and by adding sufficient organic matter to maintain an abundant amount of life in the soil.

Another confusion that can arise in discussions about rotation is how to allow for second croppings of two different vegetables in the same year. For instance, you could grow carrots until late June, then plant French beans, followed by lettuce the following spring and swedes planted after them. That is a fourfold rotation in two years and it means that a four-year rotation becomes a two-year rotation. When gardening like this, I recommend thinking of rotation in more relaxed terms, namely ‘keeping vegetables of the same family as far apart as possible in terms of time’.

Listed on the opposite page are the important categories of plants that are often closely related. For example, leeks and onions are both alliums; therefore avoid following one with another, but intersperse them with successions of vegetables from other groups. More details are provided in the relevant chapters. Note that some plants cannot be rotated, for example, perennial vegetables that grow in the same place for many years.

Perennials

Growing perennial vegetables will avoid any worries over sowing and planting, once they are established. Their roots survive the winter and they send out new leaves in early spring. In moist soil, rhubarb is ridiculously easy to keep going over several years, and choosing an early variety can give stems by the end of March. Asparagus, once established over two or three years, will crop from late April for two whole months, although quite a large area is needed to grow worthwhile amounts. Globe artichokes also need a fair amount of space but will spring up most years, and freshly picked chokes have a wonderful taste and tenderness.

SOME VEGETABLES SHARING THE SAME CHARACTERISTICS

Brassicas: All cabbages, cauliflower, brussels sprouts, calabrese, broccoli, kale, rocket, most of the common oriental greens, swede, turnip, radish, kohlrabi

Alliums: Onion, spring onion, shallots, leek, garlic, chives

Umbellifers: Carrot, parsnip, celeriac, celery, parsley, fennel, dill

Solanaceae: Potato, tomato, sweet pepper, chilli, aubergine

Cucurbitae: Cucumber, melon, courgette, marrow, squash, pumpkin, gourd

Legumes: Peas, broad beans, runner beans, French beans

Beet: Beetroot, spinach, chard

Other: Lettuce, chicory, endive, basil

Perennial possibilities abound in fruit – above all raspberries, which are so well suited to the damp British climate. Early varieties crop for a month from late June, and autumn varieties give a steady harvest throughout late summer and early autumn. Strawberries offer similar choices of different harvest times, but are a little harder to grow – you need to keep control of their runners and watch out for slugs and fungal damage in wet seasons. Consider carefully the pros and cons before planting, as outlined in Chapter 19, since you are committing to a few years’ work and harvesting.