Discovering extra dimensions of taste and colour

HERBS

Once you succeed at growing your own vegetables, and then eat them fresh from the garden, your plate will fill with deeply intense flavours in need of little enhancement. You will probably find that there is less need to use seasonings and strong-flavoured additions in cooking.

Nonetheless, many herbs grow well in containers, sometimes better than in soil where they may grow too rampantly and with less flavour. Containers can be close to the kitchen, and are good for coping with the spreading roots of mint, the seeding habit of fennel, and for helping keep the roots of French tarragon dry in winter.

Propagating herbs

It is quick and simple to buy plants at a nursery or store, but beware the problem of rapidly grown, fine-looking but ‘soft’ plants, which may struggle in a normal outdoor environment. I found this twice with bought thyme, which died the following winter, so then I grew some from seed and it has survived for many years.

Growing herbs from seed takes longer and may be tricky without a greenhouse, but the results are impressive. Sow into 3cm (1") modules in spring, thin to one seedling per module, pot into small pots after four to six weeks, and plant out two to three months after sowing. Buying a seed packet for each herb is still cheaper than buying plants, and you can have the pleasure of giving spare plants to friends or charity events.

Some herbs are easily raised from plant division, using a sharp spade or trowel to cut into a mature plant, to remove a piece of root and stem from its side. Do this at any time except summer, bedding the offcut in a pot of moist compost until it is growing strongly.

Read carefully the notes on each herb, explaining their relative performance in soil or containers. Differences in vigour make it impractical to grow certain kinds together: sage or lemon balm would smother chives, for example.

In this chapter I have categorised each herb into four grades, according to its strength of growth, to help you decide where to grow each one, and with what. Grouping them can save time – watering is easier if some are together in a large container, rather than having small individual pots. If growing in a border, the least vigorous herbs will require some bare, clean soil and full sunlight to grow well. Keep plants of the same category together, or grow them in the same spot: for example, basil can be planted in early June as chervil is finishing.

CATEGORISATION OF HERBS USED IN THE TABLES

A: Tender annuals or biennials requiring clean soil in full sun.

B: Small-leaved and non-invasive perennials requiring not too much space to grow.

C: Greedy perennials, invasive and space-demanding.

D: Rampant vigour, best grown on their own. Poor soil will suffice.

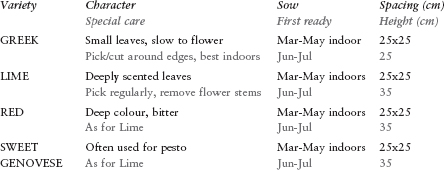

BASIL (A)

Season of harvest: June-September, produces best leaves in greenhouse / polytunnel / full sun

I have talked about basil in Chapter 9 (see page 73) as an ingredient of summer salad. There is a wide range of flavours to experiment with, for a June-to-September season of harvest. It is difficult to lengthen this, even in a greenhouse, because basil fades rapidly in poor light and cool nights. Some basils can be overwintered but will grow very little, and it may not be worth the effort since the basil flavour is most complementary to summer leaves and vegetables.

Sow and grow in warmth: April or May sowings are early enough. Be careful not to over-water young seedlings, especially in dull weather. Plant out in full sun or in a greenhouse / conservatory. Pick off larger leaves as needed and all ends of flowering stems as soon as they appear, to encourage more leafy growth (see Plate 37).

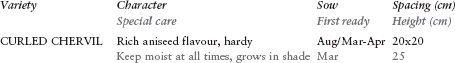

CHERVIL (A)

Season of harvest: March-May, September-November

Chervil has two particular seasons, spring and autumn, when it yields some rich, spicy leaves. It is not easy to have leaves at other times because it likes damp soil and is encouraged by light and heat to flower.

Because it has some frost hardiness, an early autumn sowing is possible, with new leaves to harvest throughout a mild winter if grown indoors. Outdoor chervil can be fleeced to encourage extra leaves before flowering stems appear in late spring. Late spring and summer sowings will yield few leaves, except in cool, damp weather.

Regular picking of larger bottom leaves, as with parsley, is good for keeping plants in full production.

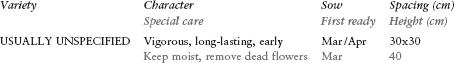

CHIVES (B)

Season of harvest: March-June and autumn

Chives can be sown in spring or raised from a divided clump, since chive plants become larger every year. Leaves are like thin and pungent spring onions, and can sometimes be picked in late winter, usually by cutting a small bunch – not the whole clump.

Towards mid-spring some flower stems will appear, blossoming into purple pom-poms whose florets make a tasty and pretty garnish: break a flower head apart to reveal its numerous mini-flowers. Leaf production diminishes by summer, unless the roots are kept constantly moist.

After flowering it is worth dead-heading before seeds set and scatter everywhere.

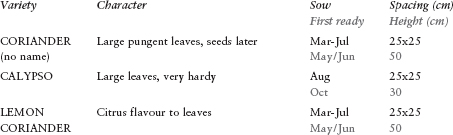

CORIANDER (A)

Season of harvest: May-October and through winter indoors

For leaves Coriander is easy to grow and tolerates frost, but often flowers before many leaves have been harvested, even from varieties that are bred for leaves rather than seeds. Late summer sowings in the greenhouse should overwinter indoors and provide leaves until May; otherwise sow in late winter for planting out in early spring.

Leaves suddenly become soft and feathery when a flower stem appears; removing it can prolong leafiness for a while.

For seed The delicate white flowers are ornamental and edible, turning into clusters of small seeds which, when properly dry and brown at the end of summer, can be used as tasty condiment in a pepper mill. I pull up whole plants and hang them in an airy outbuilding until there is time to rub out the seeds. Leafy debris amongst the seeds can be gently blown off.

For coriander in winter, sow in about mid-September in 3cm (1") modules or small pots in a greenhouse. Pot on or plant under cover and harvest occasional leaves when mild spells encourage new growth. Plants may not survive below about -4°C (25°F).

DANDELION

Red Ribbed Dandelion (actually of the chicory family) is intriguing, with fleshy leaves similar to some strains of chicory, and a slightly less bitter flavour.

The normal sowing time is spring, but early autumn is possible, as frost does not kill the roots. Leaves will be less abundant in hot weather, but should be plentiful again in autumn.

(See also Chapter 9, page 74)

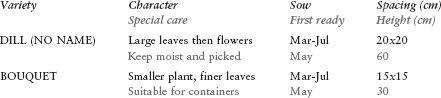

Season of harvest: May-October

Dill for leaves grows best in spring and early summer, whereas it is more inclined to make flower and seed from sowings in June or later. The leaves have a wonderfully sweet and refreshing taste, suitable for flavouring many salads and soups. Normally they have long spindly stems, although Bouquet is more compact and feathery, suitable for growing in restricted spaces.

If seed-heads are left to become brown and dry at the end of summer, cut the stem and shake out seed over newspaper. They can be sown again, used as condiment in a pepper grinder, or added to stews and soups.

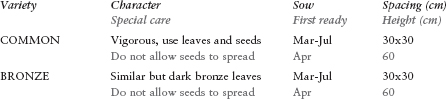

FENNEL, COMMON (C)

Season of harvest: April-October

Be careful here. Unlike Sweet Florence fennel (also called bulb fennel), this perennial is hardy and persistent, and may be invasive if allowed to seed, so I advise careful harvest of the seeds for cooking. They have an aniseed flavour, similar to but stronger than dill, while the leaves are milder and often used in fish dishes.

Sow in spring, and then by summer’s end flower stems may be 1.5m (5') high. Two colours are available: green and bronze. Both will make large plants that may smother or diminish smaller neighbours, so this fennel is perhaps unsuitable for small gardens.

See chives, page 193, for details of sowing and growing; named varieties are not usually offered. Growth is similar but leaves are flat and with a pronounced garlic flavour. Clusters of white flowers in late summer are a bonus, and edible, but beware the vigorous seedlings if seeds are allowed to drop – they can be invasive.

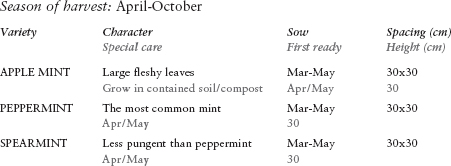

MINT (D)

A garden without mint is hard to imagine, yet mint is powerfully invasive, through roots that spread rapidly in all directions. Hence the advice to grow it in pots or containers, with regular watering for its mass of new leaves.

There is a whole world of mint flavours and leaf sizes, from chocolate mint to apple mint to tiny Moroccan mint. Traditional mint, most commonly offered for sale as plants, is spearmint (from its pointed leaves) or peppermint.

Mint is not often sown because it is so easily increased by digging up and potting-on some roots from established plants. New plants can be set out at any time of year, and need watering in dry weather.

By late spring small flower stems appear and leaf production diminishes. Before or after flowering, removing seed heads will encourage some more leaves.

PARCEL (A)

Parcel grows and looks like parsley and delivers a powerful celery flavour, so it is a useful condiment for soups, lasagne and stews. Grow as for parsley, see right.

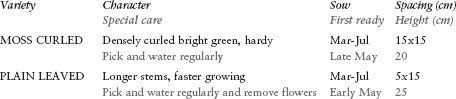

PARSLEY (A)

Season of harvest: May-November and April-May from same plants

Sow in early spring for vitamin-rich leaves all summer. See Chapter 9 (page 75) for extra details. Note that curled parsley produces leaves for longer than flat parsley, which is inclined to flower before the season’s end, so will require a second sowing in June or July. Keep picking the larger bottom leaves to make room for new growth to develop.

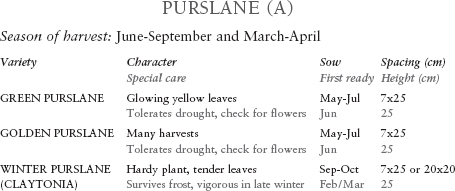

Purslane is as much a leaf as a herb, so unusual that it belongs here as well as under leaves (see Chapters 9, page 75, and 10, page 93), with succulent leaves to add a pleasant bite and notable flavour to salads. Green Purslane lasts longer than Golden Purslane in summer, and its longer stems make picking easier, while Winter Purslane is immensely hardy and brings another dimension to late winter salad.

Summer purslane has an unusual, almost invisible way of flowering and seeding, through small, angular pods that are almost hidden at the ends of its stems. These pods have a bitter flavour and will quickly set and scatter seed, so it is best to look on summer purslane as a quick catch crop, to be cleared between about eight and twelve weeks after sowing, for Golden and Green Purslane respectively.

It is a heat-loving plant, best sown between mid-May and late July, and does well in dry conditions. Three or four weeks after sowing, pick off the small rosettes at the end of all stems, then keep picking off new rosettes that grow out of those stems until there are only flowering stems left.

Winter purslane is extremely hardy, excellent in winter salads, and unlike its summer cousin has attractive white flowers on long white stems, nice to eat and slower to set seed.

ROSEMARY (C)

Rosemary is rarely raised from seed in small gardens, but it does grow well from a spring sowing, preferably in 3cm (1") modules and then potted on. By the second year you will have a large bush with aromatic, oily leaves and vivacious light blue flowers in early spring. Because it can grow rapidly, cut off most new growth after flowering and again in midsummer, especially in wet seasons. If this is not done, a lot of dry, dead wood will accumulate around the plant’s middle and its outer edges will tend to smother other plants.

SAGE (C)

Like rosemary, sage is rarely grown from seed, but follow the same procedure if you wish to. Sage also profits from hard pruning, mainly in late spring after a vivid blue flowering. Salvia officinalis is normal ‘herb’ sage, but many types of salvia have a hint of sage to their leaves and purple sage is a fine combination of beauty and flavour. By the age of four or five years, plants become woody and bare at their base, so can be worth replacing with young ones.

Tangerine sage is another member of the extended family but is unlikely to survive a British winter. Its small scarlet flowers, for a long part of summer and autumn, are both attractive and tasty, with a fine small droplet of sweet nectar in their base.

SORREL (C)

See Chapter 10 (page 93) and also Chapter 16 (page 189) for details of the different kinds of mouth-filling flavour that sorrel provides.

TARRAGON, FRENCH (Perennial D)

Seed catalogues offer only Russian tarragon, because French tarragon cannot be raised from seed and must be propagated by separating and re-potting some root off an existing plant. This can be done in autumn or spring. The two kinds have quite different flavours; French is considered more interesting. Both kinds are vigorous, needing about 60cm (2') of space around them and growing to 90cm (3') when they flower. French tarragon does not tolerate wet soil in winter, thriving best in free-draining soil or even a large pot of three-quarters sand and one-quarter compost. Cut all growth to soil level every winter; summer pruning may also be needed to keep it tidy.

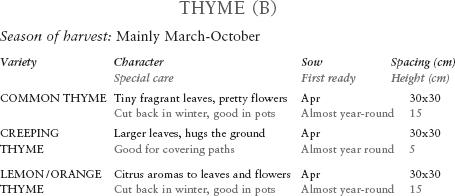

One of the smallest perennial herbs, and most suited to dry conditions, which promote longer life and intense flavour in its tiny leaves. A tendency to grow long and straggly makes it worthwhile to prune in both summer and winter. Thyme can be fragile and die unexpectedly, but new plants may appear from its seeding and it is worth sowing thyme every three or four years, to have younger, bushy plants.

The table above gives an idea of some thymes of different flavours and habits. A liking for dry soil makes them suitable for growing in pots, which need only occasional watering in summer.

EDIBLE FLOWERS

Many flowers are edible, more than are commonly used. Even if not eaten, their presence on a plate of salad leaves or cooked food says ‘This meal is special’. The following are a few suggestions.

There are also many vibrant colours in edible flower petals. They inspire the eye, surprise the palate, and make gardening, cooking and eating even more interesting.

BORAGE flowers, bright blue, are good with salad or to brighten up summer drinks.

CHARD makes tiny flowers on a long stem. Both are pretty and edible, and bitter in flavour.

CHIVE flowers can be broken into small florets of delicate mauve, with a taste of onion.

COURGETTE / SQUASH flowers are usually cooked as a dish in their own right. The classic recipe involves dipping them in batter and then frying. Courgettes in particular will produce flowers all season long; both male (on stems) and female (on fruits) are edible.

DILL flowers, very pale yellow, can be eaten as clusters of small buds. HEARTSEASE (viola) has bicoloured flowers of great delicacy.

MARJORAM is covered with pale mauve flowers at the end of summer, attractive to many insects and with a herby taste that adds zest to certain dishes. Sweet marjoram’s leaves give an oregano flavour.

NASTURTIUM flowers of all colours have a strong flavour and bring a vivid lure to table as well. Empress of India is a useful variety, for deep red flowers and dark magenta leaves, all edible.

ORIENTAL VEGETABLES all flower readily, although you may not have wanted them to. They are mostly pale yellow on tender stems and mild in flavour. Purple Choy Sum is grown mostly for its flowering stems, which bring a hint of blue to the salad bowl.

PEA flowers in late spring are an early taste of summer, recognisably ‘pea’ in taste.

POT MARIGOLD (Calendula officinalis) has deep orange flowers and is easy to grow, often self-seeding.

ROCKET flowers are white on salad rocket (Plate 39) and yellow on wild rocket. Look closely at the petals to admire some intricate patterns. Their flavour is as spicy and interesting as rocket leaves.

TANGERINE SAGE See sage, page 198.