The Garden of Eden at home

An apricot off your own tree, plums with their delicate bloom, small and large cherries, green and red apples all of different flavour – even small gardens can be home to many of these.

I assure you that home-grown fruit, picked ripe and sweet, tastes outrageously, mouth-wateringly wonderful. But it is not always easy to grow, and may have some blemishes, so read the small print carefully. Then the first successful harvest will have you hooked, and determined to try more.

I have suffered as many failures as I have enjoyed successes with organic fruit, which gives me the experience to offer advice on what really works, and where difficulties may arise.

Think out before planting out

The long-term nature of fruit growing invites careful consideration of what to plant where, with a balancing of desire and practicality. For example, it is possible to grow peaches in most of Britain, but the disease risks are high and may outweigh any good harvests.

Fruit trees are in the same place for a long time, encouraging some buildup of tricky pests, disease and weeds. Good gardening can overcome many of these potential problems, and reduce the rest to a manageable level.

I urge you, if new to fruit, to read the whole of this chapter in order to gain a feel for what is achievable in relation to your garden and your lifestyle. Then you can peruse a catalogue of fruit trees and bushes, or visit a nursery, with much better understanding of what is worth buying and planting. Often this will be rather less than is claimed by the sellers, and a bit of knowledge will save you much time and money.

As an example, consider the season of harvest by imagining when fruit would be of most value to you, or might go to waste. Most plums and gages are ripe in August, when you might be on holiday. Apple varieties ripen at different times: some apples go soft by the end of summer, while some can be stored into the following spring, when all fruit is at a premium.

The size of your garden may be a crucial factor. If trees are too crowded, fruit will not set or ripen well. Consider the space-saving options of dwarfing rootstocks, and of growing trees against walls or in containers.

Rootstocks

Most fruiting trees are grafted on to roots of different trees, called rootstocks, whose vigour is usually less than the main tree. Without rootstocks there would be little chance of growing tree fruit in a small garden, and waiting times for fruit after planting would be much longer.

Apples have the most options, and their most dwarfing M27 or M9 rootstocks are suitable for most gardens, often giving apples in the second summer after planting, and rarely growing more than about 3m (10') high or wide. Size can be further reduced by twice-yearly pruning. For cherries, Gisela 5 rootstock makes it possible to have a small tree with plenty of fruit that can be netted.

The best approach is to check what rootstock is offered, together with the expected size of its tree. All fruit tree labels or catalogue descriptions should contain this information.

Planting

Planting season for bare-rooted fruit trees is November to May, and the earlier the better. Even in winter, roots can be settling in and drainage water will be packing soil all around them. March and April plantings are more likely to need watering in a dry spring, as will container-grown trees, especially as they can be planted at any time of year, even in summer.

Small trees are cheaper to buy, easier to plant, and establish more rapidly than large trees.

As long as your soil is reasonably dark and crumbly, simply dig a hole a little larger than the rootball, drop it in and firm soil around the roots as you back-fill. A large hole with some added compost is worthwhile for pale clay or ex-building sites, but not fresh manure, which might encourage rapid but less-healthy growth.

Damaged roots can be trimmed back with secateurs and thick rootballs of container-grown trees can be unwrapped a little so that some roots are free of tangle and ready to grow outwards. Some suppliers offer small containers of mycorrhizae for adding to soil around tree roots, and these will almost certainly enhance growth significantly, depending on your soil’s health.

Staking is often necessary, for the first couple of years and with short stakes preferably; again, check the instructions supplied with each tree.

A major cause of crop failures is late frosts killing early blossoms, so if your garden is in a hollow and prone to late frosts in spring, avoid planting fruit tress which flower early in spring, such as plums, pears and apricots. Apples are more likely to succeed.

Weeding and watering

Keep soil around small trees clear of weeds and grass, at least 30cm (12") in all directions, so that they are not deprived of moisture and nutrients. A 5cm (2") annual dressing of compost will benefit them, and some water in dry summers can make quite a difference to the size of harvest on dwarfrootstock trees.

Shaping trees

All trees can be trained to whatever shape and pattern fits best into any garden, always provided the vigour of the rootstock matches the desired size and shape. For example, cordons and espalier apple trees require either M9, M26 or MM106 in order of increasing vigour and size of the tree. Any variety can be chosen on these rootstocks. Specialist fruit books go into the details, but common sense is often enough to suggest how to train branches against a wall or along a fence, by tying in or wiring up those growing in the right direction and cutting off ones that are not. All nurseries listed in Resources will offer sound advice, often through their websites.

Patience is vital, since best results often come from planting small ‘maidens’ that are simply 1-2m (3-6') stems, out of whose buds will grow twigs that become branches. A maiden has short, easily transplanted roots and adapts more quickly to a new site than a larger tree, with less risk of drying out in the first summer – and small trees cost less.

Pruning and thinning

Q. Why prune, when trees and bushes produce without it?

A. To have better-sized, nicely coloured, easier-to-pick, more-frequent and top-quality fruit, through judicious cuts, which stimulate trees into making new and healthy growth.

I used to hate pruning, feeling it an unnatural thing to do. But I have had enough harvests of small, diseased or difficult-to-harvest fruit to make me appreciate the wisdom of cutting out wood or stems at certain times of year. Thinning excess young fruit is another worthwhile little job in the same vein.

Apples like a mild climate, but with cold enough winters to ‘vernalise’ apple trees i.e. make them flower every spring. Their blossom is a joy in its own right: clusters of pink and white every May, which according to weather and insects will become mature fruit between late August and mid-October, depending on region and variety.

Apples have the largest section of this chapter because they are the easiest and most reliable fruit to grow in most of Britain, with the greatest choice of flavours and culinary possibilities.

Rootstocks

Apples are always propagated from cuttings that are grafted on to rootstocks of varied vigour. This is because self-sown apples do not grow ‘true to variety’, take a few years to start cropping, and grow into much larger trees than most of us want.

Check carefully which rootstock you are buying: it is as important as the tree variety, and it should always be stated. Note that M9, probably the best choice for small gardens, has rather weak and brittle roots. A permanent stake or support will therefore lengthen the life of its tree and enable it to fruit better. More vigorous rootstocks can grow without stakes after two or three years of establishing themselves.

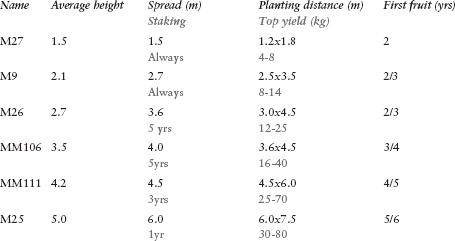

The table below outlines some possible tree sizes and planting distances for different rootstocks, how long they need staking, the number of years between planting a maiden and first fruiting, and how much fruit a mature tree might yield.

Most apple trees fruit best when other varieties are flowering nearby, so that insects ‘cross-pollinate’ and help fruit to set. Fortunately, most varieties flower at about the same time, so as long as you have two or three different ones there should be no problem. Bramley and Winston are two of a few self-fertile varieties, setting plenty of fruit without other pollen nearby.

EATING APPLES

Choose a good variety for your location, and keep improving your soil after planting, with some good compost on the surface or, perhaps best of all, some well-rotted horse manure. By the second autumn, if you have trees on M9 or M27 rootstocks, there will be really good apples to savour. And I mean savour, because I rarely manage to buy apples with a depth of flavour and quality of flesh to compare with my own.

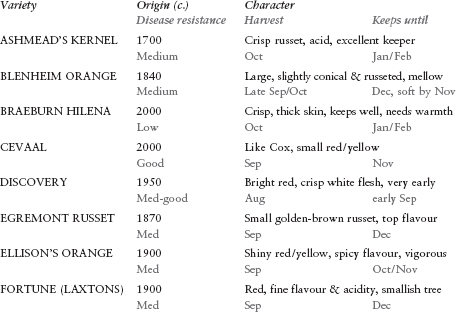

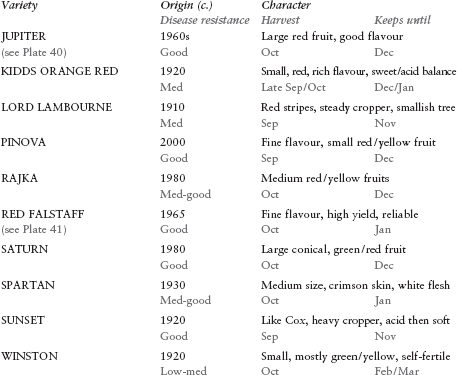

The table below is to help you decide which varieties are most suitable for your garden. It includes varieties that I have succeeded with organically, and which have been recommended to me.

Scab is the worst enemy of eaters because its dark and sometimes large, indented spots can really spoil the appearance of an otherwise good fruit. The table column headed ‘disease resistance’ refers mostly to scab, and in areas of high rainfall it is important to plant varieties with good resistance to it. I have not included Cox’s Orange Pippin because it is more susceptible to disease than other varieties listed.

Eaters are sweet to eat, when in season and properly ripe. Each variety has an average maturity date, for example August-September for Discovery, October-November for Sunset and November-January for Kidd’s Orange. To have apples after that is not so easy, whatever the description may say, because fruits often shrivel a little and, in my experience, ripen earlier than they are meant to. See cooking apples, below, for late eaters.

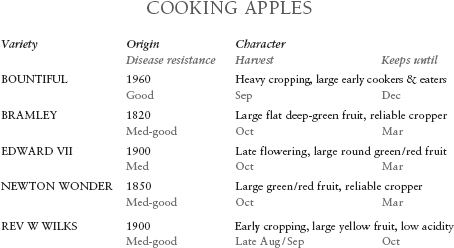

Cooking apples have higher acidity than eaters and are often easier to grow because of better disease resistance. They also crop more heavily.

The classic cooking variety is Bramley, and it deserves its reputation, succeeding both as small trees and as large old ones, which continue to drop vast amounts of dark green apples every year. If picked and stored, they turn more yellow in late winter and can become just sweet enough to eat, if still acidic. Newton Wonder is better as a dual-purpose apple, good to eat in February and March.

Bountiful, an exciting relatively new variety, makes a good companion to Bramley, being ready earlier and becoming edible by November as it ripens. It stays crisper than many eating apples and is often large, especially when thinned out on the tree in summer.

CIDER APPLES

These are more tannic, indicated by how they dry the mouth out, after a briefly pleasing sweetness. Note that eaters and cookers can also be fermented into ciders of pleasing flavours, but do not press too many cooking apples or the cider will be over-acidic.

CRAB APPLES

Crab apples are small, acidic and tannic, almost inedible but rich in flavour for making jelly. They are also highly ornamental, for blossom and fruit: Golden Hornet has clusters of small bright yellow fruit that stay on the tree until December, and John Downie bears larger red crab apples. Other varieties are available, from Walcot and Blackmoor nurseries for example.

Pruning apples

Pruning is more an art than a science, because few people agree on all the details. I aim to keep it simple, and advise you to think in winter of removing about one third of last season’s growth, either by cutting off whole branches or by shortening them. The aim is to have:

• a well-spaced framework of main branches

• some fruiting spurs – knobbly protrusions or short twigs

• enough other branches to make leaves for nourishment of present fruit, without shading it too much.

Pruning is mostly done in winter when leaves are absent. If overdone, the tree may make vigorous new stemmy growth in the following season, somewhat at the expense of fruit. Summer pruning in addition to winter pruning can spread the load and help in restricting or re-directing growth, without trees making excessive new growth to compensate. Usually it is done from about mid-July to early August, and involves shortening new stems by a half or more, or removing them altogether on trees of special shape. Also remove any leaves that overhang fruit so that sun can ripen its skin to deeper red colours.

Thinning fruit

In years of plentiful fruit, some will fall in June and July (the ‘June drop’), but enough may still remain on the tree that apples are too cramped to grow large. I usually cut or carefully twist off one apple of every remaining pair, or two out of every three, as long as I can reach them, by about the middle of July. Larger fruit are then possible, and the tree is spared from supporting a huge harvest, making it more likely to fruit well the following year.

Harvesting

If apples fall they bruise and will eventually rot, so it is important to pick them before they are so ripe as to fall in an autumn gale (cider apples excepted). They mostly need picking before full ripeness is achieved, between mid-August and mid-October, depending on variety and region. Eaters usually taste both sweet and acidic at picking time, while cookers are mostly firm and green.

Handle apples carefully, laying them out on trays or stacking them in boxes in a cool but frost-free place, and check to see when they ripen – shown by yellowing of the skin, with their flesh becoming softer and sweeter. Or eat them earlier if you prefer crunchy fruit with more ‘bite’.

Problems

Non-organic apple growers and gardeners use a range of toxic sprays, mostly fungicides and some pesticides that contain organophosphates. Your homegrown fruit will be clear of all these poisons but may not avoid the codling moth’s maggots, aphid damage to young leaves, black scab fungal patches on leaves and fruit, or canker lesions on branches which must then be cut out.

Growing resistant varieties is a good start – for instance, Sunset rather than Cox, which is unfortunately difficult to grow organically. Use the table on pages 205-206 to find varieties with good resistance. Correct planting distances and good pruning help to keep air and light around the leaves. Healthy, well-drained soil with some compost or manure, but not over-manured, also helps.

Much depends on the effort and money you want to invest in achieving blemish-free fruit. Codling moth traps hung in trees from May and replenished in July, as well as grease or glue-bands for the trunk from late September, are two effective solutions, provided you remember to apply them at the right times.

The bottom line is that many organic apples are less fine in appearance than chemically grown ones, but are clean of invisible residues – and so is the trees’ environment. The choice is ours.

Apple crumble

Our favourite crumble topping is:

100g (4oz) butter

80g (3oz) wholemeal flour

50g (2oz) muscovado sugar

80g (3oz) porridge oats

1 apple per person

This serves 4-6; I usually double it for Sunday lunch when we have visitors. Peel, core and slice apples. Butter a large shallow dish. Arrange apples and sprinkle with cinnamon or nutmeg. Add a couple of tablespoons of apple juice or water. Rub the butter into the flour, then add the sugar and oats. Sprinkle over the apples and bake in a hot oven c.180°C (350°F) for 20-25 minutes.

OTHER COMMON TREE FRUIT

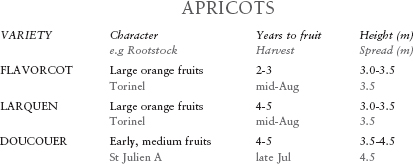

Note that apricot varieties, and many other fruit trees, have named rather than numbered rootstocks. In order of size they are Pixy, Torinel and St Julien A.

Varieties

There have been some breakthroughs in apricot breeding, such that varieties now exist for planting in open ground as far north as Hadrian’s Wall (Tomcot). But a sheltered, sunny aspect is nonetheless always recommended!

Apricot trees are vigorous, even in Britain, so in small spaces look for a tree on Pixy rootstock.

Some of the new varieties, such as Flavorcot and Larquen, bear large fruit almost the size of peaches. I harvested 15 large apricots in Flavorcot’s second summer (on rootstock Torinel), planted as a maiden the previous spring. It flowered in early April, later than usual after a cold winter, which just avoided a late frost. Now the tree is six years old and almost too large, in spite of regular pruning.

Apricots are one of the first fruit trees to blossom in March or April, and most problems arise from either frost on the flowers or lack of insects for pollination. Tickling flowers lightly with a soft brush may be necessary.

Planting

Because spring frost does more harm to the blossom than cool winds, be sure not to plant in a frost pocket. Even some south-facing walls can be treacherous, because their warmth encourages early blossom but may not keep ice off flowers if the wall is at the bottom end of sloping ground.

Growing

Torinel and St Julien A rootstocks are quite vigorous, and more suitable for an open orchard area than a confined wall space. Little pruning is recommended or necessary, only to remove any crossing or obstructing branches, and is best done in late spring. Fan training against a wall is possible, but will require summer pruning to keep growth in check.

Harvesting

Fruits look well coloured and ripe for at least a fortnight before they are soft and sweet. A gentle squeeze every now and then will reveal the gradual change to juicy flesh. When ripe they should come off readily in your hand – a moment to really savour!

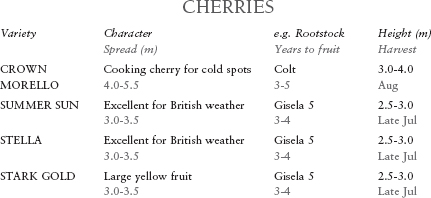

The RHS (see Resources) has excellent information on making the most of dwarf cherries. For the keen amateur fruit grower, these are an exciting prospect.

Look out for trees on Gisela 5 rootstock, which is becoming common as it proves an ability to keep growth manageable whilst allowing a plentiful harvest. Smaller trees also mean that small gardens can accommodate one or more trees, preferably in full sun, except for Morello, which is often grown against north-facing walls.

Pruning

Cherries are susceptible to silverleaf (see page 216) and canker (see page 208), so do not prune them in winter: the best times are after flowering in April and after fruiting in August. Exact pruning details depend on whether you are growing a bush tree or fan training in the open or against a wall. In essence, April pruning is to shorten abundant new stems and allow new branches to develop. August pruning aims to remove crossing branches or large branches whose fruiting value is diminishing.

Harvesting

Cherries swell rapidly in their final fortnight and in wet summers they may split – while still good to eat, they will not keep if this happens. Pick them with stalks attached if they are not for immediate eating, but their allure makes the passage to table a very tenuous one!

Problems

The scourge of cherries is birds. You will probably need to net or cover the tree or to use some other fail-safe way of keeping birds off the fruit. Stark Gold’s yellow fruit are sometimes less attractive to birds. Netting small trees on Gisela 5 rootstock is entirely feasible, because their full height and spread will be about 3m (10') even without much pruning, although cropping will be better for it.

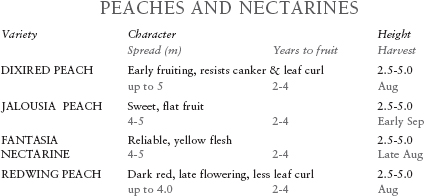

Modern breeding has helped, but peaches and nectarines are still plagued by leaf curl, caused by excess moisture on their buds in winter and manifesting as curling, even shrivelling leaves through spring and early summer, sometimes to the point of trees dying. See below for remedies.

Varieties

The table on the previous page reveals some of the many possibilities – a variety with leaf curl resistance is definitely worthwhile. On the other hand, flat peaches such as Jalousia and Oriane have flavour that compensates for extra work in combating their susceptibility to disease.

Rootstocks

Two main choices are St Julien A, for more vigour, and Montclaire, for less.

Planting

If you have a wall or fence with a southerly orientation, this will be good for peach and nectarine. Fan training allows heavy yields, while less vigorous rootstocks such as Montclaire and Myrobolem can reduce vigour enough to make growth more manageable.

Pruning

Early spring is good for pruning – after flowering and before leaf emergence: being able to see the pretty white flowers helps conserve them from secateurs. For young trees, train larger stems into a fan shape behind wires on walls, shorten them by about a third and cut off all branches coming away from the wall. Also in summer, cut off all outward-growing branches and clear leaves away from developing fruit. Thinning any clusters or pairs of fruit will help growth and ripening of the remainder.

Harvesting

Fruit may colour for a fortnight before ripening, which is revealed by touching to see when they start to soften up. You may even smell their fine fragrance, and tasting them is a notable experience.

Problems

There are solutions to the dreaded leaf curl even without chemical fungicides. Probably the safest and most reliable is to make a shelter of wood or plastic that protrudes from wall or fence above the tree to at least half a metre (2'), sufficient to keep most rain off stems in winter. Another is to spray Bordeaux mixture (copper sulphate) on bare stems in February and March.

Drier parts of Britain are definitely most favoured; the wetter west and north carry more risk of problems. Leaf curl can strike rapidly: my Newhaven peach cropped well for three years without protection or spraying, then suddenly died the following July. This could happen to any unprotected peach and nectarine trees after a wet winter. So I have planted a pear instead.

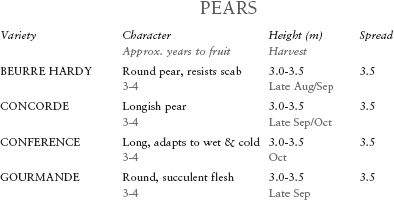

Varieties

With apples, a crop is almost certain, but not with pears. They are more prone to disease and to late frosts on their early blossom. Even when a crop is achieved and picked, they can go soft and become inedible for want of being checked regularly for ripeness.

Plant the variety of your choice in as frost-free a part of the garden as you can spare. I have tried many varieties and find Conference, the most readily available, to be one of the most reliable. Consistent yields of fruit ripen reasonably slowly, in mid-autumn, without going soft too quickly. Another interesting variety, ripening slightly later with some resistance to scab, is Beurre Hardy. Resistance to scab is especially important in wetter regions, while those in the drier south-east of Britain stand more chance of healthier crops.

Pollination and fruit set are generally improved by the presence of more than one variety. Concorde, although self-fertile itself (like Conference), is an especially good pollinator.

Rootstocks and planting

There is much less variation in rootstock vigour for pears than for apples. Most pear trees are sold on the same rootstock, Quince A, which requires a spacing of about 3.5x4.5m (11'6"-14'6"). Staking is recommended for at least three years, more likely five. If on Quince C, trees can be planted a little closer together, will be about a metre (3') shorter and may fruit a little earlier. Planting against a wall with some southerly aspect is good both for extra warmth and for the pruning disciplines imposed by training growth in two dimensions.

Pears are keen growers and readily make long vertical stems that rise out of reach, especially after hard winter pruning, which should therefore be less severe than for apples. Summer pruning is invaluable to cut back long new stems, to remove unwanted ones and, for example, to shape branches into a fan pattern against walls.

Harvesting

This can be tricky to judge as pears are best picked unripe – but not too unripe if you want good flavour. Move the bottom of a pear gently outwards in a circular motion: if its stem comes away from the tree, then picking time has arrived, but if it holds firm then wait another week or so before trying again. Pears are usually firm when picked– except for early varieties such as Williams – and need laying out to watch for yellowing and softening, sometimes over many weeks. Keeping them cool will slow ripening but may also stop them becoming tender, although they should still sweeten up.

Problems

Fungal scab on leaf and fruit is quite likely to infect your tree after a season or two. In wet regions it may be worth trying a variety such as Improved Fertility, as well as trusty old Conference.

Dorset window pudding

This is a very useful pudding topping that lends itself to many fruit – rhubarb, apples, plums. Fits in a 26cm (10") flan dish.

250g (9oz) pears, peeled, cored and sliced

50g (2oz) butter, 50g soft muscovado sugar, 1 egg

75g (3oz) wholemeal flour (25g/1oz ground almonds can be substituted for 25g flour)

1 teaspoon baking powder, 2 tablespoons milk

Butter the flan dish and lay the pear slices in a nice pattern. Cream together the butter & sugar, add the egg, flour and milk. If very stiff, add a little more milk. Spoon on to the pears. Bake at 180°C (350°F) for about 20- 30 minutes.

My observations on plums concern rootstock, above all. I have compared various grafted plum trees over the years with some that I have grown from suckers, therefore growing on their own roots. I find that the latter have cropped better and grow more healthily, above all with no infection from silverleaf (see ‘Problems’, overleaf).

However, they make more suckers themselves – annoying if they are close to some cultivated ground, which they also feed from as they grow large, up to 6m (20') high quite easily. Their shape is quite different from that of apple trees – more vertical and graceful.

For bought trees there are often two choices of rootstock: Pixy is the one for small gardens; otherwise the more traditional St Julien A makes a medium-sized tree. Greengages are more difficult than plums as they need extra sun and warmth, and crop a little less readily.

Varieties

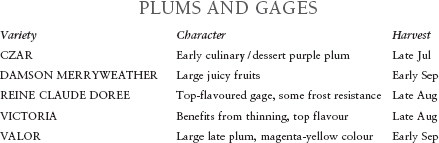

The table above contains only a few of the most common varieties, so there is plenty of choice. Notice that you can have plums and gages for more than a month by combining early and late varieties. Thinning takes time but is really worthwhile if you want decent-sized fruit and can prevent boughs breaking with too many plums in good years. Smaller trees on Pixy rootstock are much easier to manage in this respect.

Planting

Note the different planting distances according to rootstock: 3x3.6m (approx. 10x12') for Pixy and 3.5x4.5m (approx. 12'x4'6") for St Julien A. Staking is advised for at least three years.

Harvesting

The first fruit to drop may have maggots inside, rather like early ripening apples with codling maggots. Then from mature trees there can be an avalanche of fruit in seasons when late frosts have not damaged the blossom. Pick soft fruit off the tree or shake the trunk to make ripe ones fall, giving you some interesting opportunities for jam making and bottling.

Pruning

Most pruning consists of removing branches that are crossing or duplicating others, and the main consideration is to avoid doing it in winter – see overleaf.

Silverleaf is a fungal disease that kills plum and gage trees, usually through access to a tree’s wounds in winter and early spring, after pruning is done when the tree is dormant. Hence it is always recommended to prune plums and gages between May and July – preferably in June, when rapid growth will heal cuts quickly.

Plum moths and sawfly are the source of maggots in some fruit. Moths can be caught by hanging pheromone traps in trees at the end of May for about ten weeks. One trap can look after three trees, but you may well have enough good fruit to do without them.

Clafoutis

The classic recipe is for cherries, but it lends itself well to other fruit such as gooseberries, and raspberries.

750g (1lb 10oz) plums, 80g (3oz) flour, 80g sugar, 2 eggs

1 sherry glass of brandy or other alcohol (optional)

1 pinch of salt, ½ litre (18floz) milk

Stone the plums. Put in a buttered gratin dish or a circular dish of 26-28cm (10") diameter. Sprinkle over the alcohol. Make a batter, whisking flour, sugar, salt and eggs. Heat the milk to boiling point, then whisk into the batter. Pour over the fruit and cook in a hot oven c.180°C for 35-40 minutes. Serve warm.

LESS-COMMON FRUIT

Figs and grapes are two worthwhile fruits to grow, especially in warmer regions or sheltered gardens. They are covered in less detail here because they are grown more rarely, but are not especially difficult if you respect the basic points I mention.

FIGS

Fig trees are difficult to bring into fruit unless their root run is restricted, to dampen their vigour – see right. They are also susceptible to late frost if leaves emerge too early. Baby figs form in late summer but are killed by frost, while eating figs start to develop in autumn and then grow again from April, to ripen by August. Brown Turkey is the standard and a very reliable variety, while Violetta is unusual for its ability to fruit without a restricted root run. Some pruning each winter will encourage fruit of better size and quality, and make it easier to find amongst abundant foliage.

Grapes of suitable varieties will yield well in sheltered, sunny spots and in drier regions. Look for varieties with mildew resistance, because crops are easily lost if mildew-prone varieties suffer damage to their leaves in wet summers. Four outdoor varieties for eating grapes are Alphonse Lavalée, from 1850s France, with small, dark red fruit; Dornfelder, for slightly larger red fruit; Phoenix, for small, almost seedless white grapes with a hint of Muscat flavour; and Perlette, for almost seedless larger white grapes. Picking is usually through October and hard pruning is needed in late winter or early spring – pay attention to instructions with plants, and do not skimp on pruning.

TREE FRUIT IN CONTAINERS

Small fruit trees will grow and crop in containers, but remember that watering is a regular necessity for about six months, and some feeding will also help growth. An organic tomato feed is suitable.

APPLES

If apples are grafted onto M27 or M9 they can be grown in large pots, with some extra summer pruning to restrict their growth. A dwarf variety, Croquella, with red fruit in September, is well suited to pot growing.

CHERRY

The variety Cerasus Maynard Mini Stem grows no higher than 2m (6'), requires no pruning and offers fruit in early August.

FIGS

Since fig trees fruit better in restricted root runs, containers suit them well. Any variety should be possible in a pot of about 60cm (2'); note that some are especially heat-loving and fruit most reliably in a greenhouse or conservatory – check the details when buying a young tree. Yields will not be huge off small trees, but they are ornamental too, with their dark green, indented leaves.

NECTARINE

A variety called Nectarella is sufficiently slow growing to be viable in a large pot. Keeping it in a dry place between November and March will reduce the risk of leaf curl, as long as you are strong enough to move the pot and tree.

As with nectarines, pot growing offers the chance of minimising leaf curl by hibernating trees indoors. A variety called Bonanza is extremely slow growing and should require no pruning.

PEAR

Yields of pears can never be large in containers but some fruit are definitely achievable. Look out for Garden Pearl, which needs no pruning and has a maximum height of 2m (6').

NUTS

ALMONDS

Almonds can be grown in Britain, having similar climatic tolerance to plums and flowering at about the same time – therefore vulnerable to any late frosts. They are vigorous, up to 6m (20') high, and two trees are needed for good pollination. Their leaves resemble those of peach trees and so do the nuts, encased in green flesh that can be mistaken for an unripe peach. Most available varieties have resistance to leaf curl.

HAZELNUTS

These grow so, so easily, and squirrels are so, so good at finding them before we do. I know of no easy answer, but cobnuts (large hazels) such as Kent Cob are still worth a try, edible as green nuts from late August, on bushes that grow as clumps of upright stems, 3-4m (10-13') in height. Older bushes will yield heavily, and in 2009 I picked 2.4kg (5lb 2oz – with shells) – off a six-year-old bush.

WALNUTS

Walnuts suffer similarly from squirrels and take much longer to grow, as well as needing much more space – say 8-10m (26-33') between trees – and it is recom mended to plant two different varieties for cross pollination and good yields. Modern varieties claim to bear within five years, about half the time previously needed, and usually come into leaf late enough to minimise the risk of damage by late spring frosts.