A little known fact about pigs is that they can jump. Not high enough to warrant establishing a porcine Olympics, but to an altitude that is quite impressive given the pig’s physiognomy and more than sufficient for the purpose Tereza has in mind.

Why, it may be asked, do pigs jump? The answer is simple. Food. The word was invented for them. Given the prospect of food a pig will go to any lengths, including vaulting into the atmosphere, to eat. And what food ensures maximum lift in an airborne pig? Truffles.

Tereza’s quest for truffle-jumping pigs involves only a minor detour to Provence on her return to Paris from the Riviera. She strikes a bargain with a local farmer, which includes the provision of a pig-beating staff, and sets off down the motorway with a truck-load of squealing aviators.

On arrival in the capital she meets with an artist friend who has agreed to lend her his studio on the Left Bank. This is attached to a garage via an automatic roller shutter, through which Tereza herds her new friends.

Over the next few days Tereza makes frenzied preparations. First, the studio is plastered floor to ceiling with black plastic sheets, creating the impression of the inside of a square dustbin. Next, she installs lava lamps and other psychedelic light effects, transforming the dustbin into a disco for slow dancers. Finally, she hires a motorised builder’s hoist with all the accoutrements. The hoist, used mainly for transporting bricks to first-floor level, consists of a platform attached to a mechanical arm, which is operated by an impressive array of levers.

Tereza also acquires a harness similar to the one that was defeated by Boss Olgarv. But Tereza’s version is guaranteed by the Japanese cousins of the Teutonic robots. It will perform any task required.

Tereza contacts Shit TV to borrow some equipment and agrees to give the network exclusive rights to the forthcoming show. She despises Shit TV for its role in Tomas’s death and regards the network as her mortal foe, but life has taught her to be practical, and she remembers Tomas’s lesson that sometimes a small evil leads to a greater good.

Her final task is one of omittance: she doesn’t feed the pigs for a week. By the end of it, they are ready to leap to the stars in search of lunch.

With all her arrangements in place, Tereza dials a number.

‘That evening – I can think of nothing else,’ she says. ‘You afforded me the greatest pleasure of my life. I want to pay you back.’

‘Where and when?’ Hank asks.

Moments later Hank is en route to an urgent meeting on the Left Bank. He telephones his wife from the car. ‘I’m working like a dog. Don’t wait up.’

When he arrives at the studio, Tereza tells Hank through the intercom that she’s been expecting him. He takes the fateful step through the magic portal. Dancing colours beckon him through an open door at the end of an entrance hall.

Hank’s heart begins to race, goes into shock on seeing Tereza.

She is dressed top to toe in a single black plastic garment, which clings to her body like a wet rag. She stands with legs apart, shoulders back and hands glued to her hips. As Hank’s eyes adjust to the shifting colours of the pleasure chamber he sees in clear relief the parts of Tereza’s body that are exposed through gaps in the outfit. Eyes, nose and the sensual lips peep through slits in the hood; breasts point upwards, forced through two tight openings; in place of a plastic crotch, he can see the triangle of her sex. Were Hank a jumping pig and Tereza a truffle located on the farthest star in the galaxy, he would reach her in one leap.

‘Strip,’ says Tereza.

Seconds later, Hank is her naked slave, in front of a bank of concealed cameras.

‘Lie face down on the platform,’ she commands.

He prostrates himself.

Without ceremony, Tereza straps him into the harness. She touches the parts of his body she wants him to lift or move and fixes the straps around his chest, arms and legs. She is meticulous, making minute adjustments on the harness fastenings until his incarceration is complete.

Three words describe Hank now – naked, trussed and prone.

Tereza steps off the platform and swings its mechanical arm, to which is fixed a dangling length of chain, over her victim. She attaches the chain to a loop at the back of the harness and tugs it as hard as she pulled the bacon ball a few weeks earlier. There is no doubt that the harness will hold.

Lying with his head to one side on the platform, Hank attempts to say something. But Tereza doesn’t look or listen. With calm concentration she engages the control arm. She flicks a switch and a mechanical noise signifies that the machine is alive. She presses another and Hank rises into the air. When he is chest-high off the ground she presses ‘stop’. Hank is left swinging like a caged captive in some medieval contraption.

If Tereza were to be offered her life in exchange for remembering one word of the banalities spoken by Hank at this moment she would lose. She’s an avenging angel now, sword unsheathed. Except that her sword is a brush, which she dips into a large pot of truffle oil.

Lying naked and horizontal four feet up in the air, gravity has a predictable effect on Hank’s penis, which Tereza proceeds to paint. She gives it several coats, before stepping back to admire her artistry.

Tereza before – dazed, disgusted, sprawled on the floor spitting shit from her mouth. Hank now – ecstatic, euphoric, suspended naked in the air with his genitals coated in truffle oil. Next door a room full of truffle-obsessed jumping pigs, who have eaten nothing for a week.

A demented disco and a rabid raptor …

It’s the series final of ‘Dwarf Slam Disco’ on Shit TV and the Great Bear can’t be disturbed. Even the Iranian Hawk and Boss Olgarv must wait outside for the show to end.

The scene opens in a cavernous circular arena with brick walls, a wooden floor and dim lighting overhead. A big buzzing crowd is seated in tiered rows running up to a pitched roof. After the American commentator delivers a long introduction, the lights fade and the arena’s great entrance portal is flung open. A spectral beam floods the floor as from a spaceship door opening. Instantly music starts to pulse and a huge disco rig descends from the ceiling, flashing in time to the rhythm. This continues for a full five minutes, while the commentator builds the tension further with ‘Are you ready?’ questions. The crowd starts to chant: ‘Slam! Slam! Slam!’

After a while, darting shadows can be seen in the light streaming through the entrance portal. At first these appear indistinct but slowly they take shape and the crowd, straining forward, sees the outline of little mobile figures. And as the music’s volume and tempo doubles, a thousand rollerblading dwarves stream into the arena to the crowd’s tumultuous applause.

For the next ten minutes the dwarves circulate clockwise around the space at great speed while the crowd claps in rhythm. As they pass floor-mounted cameras and microphones they make menacing faces and nasty noises. These are transmitted to giant screens and speakers suspended overhead: the crowd cheers the more offensive offerings.

The lights fade momentarily, then go out altogether, plunging the arena into darkness. The crowd explodes in a frenzy of excitement and the commentary rises to fever pitch. This is it. Only seconds to go.

An eardrum-bursting klaxon sounds, multi-coloured disco lights ignite, music shakes the walls. The crowd erupts to its feet as the dwarves slam into each other – fists flying, heads butting, legs kicking, teeth biting, elbows shoving: an orgy of pain and violence. From above they resemble a huge catch of fish, just landed, thrashing desperately on a fisherman’s deck; a mosaic of a short, brutal, ugly battle. As stretcher bearers carry off the casualties, the mass of rollerbladers is trimmed to a core.

These are the top slammers, two dozen or so in total, expert with their legs and heads. A savage-looking dwarf, with blood streaming from his forehead, pivots on his blade and, incredibly, brings an airborne boot into the face of an opponent. He then swings round to defend against an attacker, arches back as if on a spring, and smashes his forehead into his opponent’s nose. The crowd’s ecstasy of clapping, cheering and chanting now drowns out the commentary. Ten minutes later just two dwarves are left standing in a pool of mess and blood.

This is the final slam. The dwarves take position at either end of the arena, pawing the floor like bulls about to charge. They snarl, slather and shout abuse. The klaxon sounds and the dwarves take off towards each other at tremendous speed, swinging low on their skates. As they reach the centre, they squat down before leaping high into the air like uncoiled springs. Their foreheads clash with a bone-splintering crunch which echoes in the hall. One little body now lies slumped. The winner is paraded around the arena to ecstactic cheers and applause.

Only now are the Iranian Hawk and Boss Olgarv admitted to the Great Bear’s lair. The raptor squawks uncontrollably and flaps about the chamber shitting, his feathers flying. Boss Olgarv manoeuvres his detachable stomach into a corner to watch and listen.

‘The pipeline between our two nations is a success,’ the Great Bear begins. ‘In addition to the technology we’ve provided and our diplomatic support, you have my thanks.’

The Iranian Hawk flaps over to a table, sending a lamp crashing to the ground. Spooked, he begins thrashing around in circles, squawking dementedly.

‘But for the final plan to succeed,’ the Great Bear continues, ‘the pipeline must be extended. You understand this, don’t you?’ He pauses awaiting a response. ‘It’s critical for …’

Another squawk cuts him off. Inexplicably, the Iranian Hawk is lying on his back in the middle of the room, flapping his wings and making involuntary head movements. His pupils dilate and his beak opens and closes in short sharp spasms. He appears to be suffering a fit.

‘I must stress,’ the Great Bear continues calmly, ‘that without the extension …’

The Iranian Hawk gives an ear-piercing shriek and is airborne once again. The Great Bear signals to his attendants, who roll back the boulder to allow the demented bird to escape.

Boss Olgarv steps from the corner to begin his interview.

‘Sir, may I begin with a request?’ he asks. ‘I’m aware of the pipeline of which you speak but not its extension. Enlighten me a little about the plan. The knowledge will fortify my resolve.’

‘Revealing the final plan,’ the Great Bear replies, ‘is out of the question. But I can put some points into context. As you’re aware, our strategy is to subvert the West by flooding it with money. Clearly, the greater the funds at our disposal the more powerful our ability to spread our nihilistic message.’

‘I see,’ says Boss Olgarv, ‘but this only influences a few – the oversized-collar wearers and dancers with champagne bottles.’

‘Nonsense,’ replies the Great Bear. ‘Take football. You yourself own a team. “Ballers”, with their vulgar life-styles, infantile opinions and getting-away-with-it abuse of women, are an excellent symbol of the perversion of values and culture. What young Westerner doesn’t dream of becoming a footballer? You think it’s the ball he wants?’

‘But how are these values to spread?’ asks Boss Olgarv. ‘How is the money supply to endure?’

‘That’s my business with the Iranian Hawk,’ replies the Great Bear. ‘But soon the pipeline will be extended, the venom required to execute the final plan prepared. Your task is to devise a means of spreading it across the West in conjunction with my general, King Rat. A manly weapon, something that borrows from our past but embodies our new virility.’

‘A great honour,’ replies Boss Olgarv. ‘I shall design it personally. A final question, if I may.’ He pauses and the Great Bear nods his consent. ‘Why was Tomas’s liquidation so vital?’

‘Tomas was dangerous,’ replies the Great Bear. ‘A celestial maniac. He understood what was wrong with the world and sensed our plan. He might have ruined it. What if he had started a counter-reaction – an age of reason and moderation? He had to be stopped. Are you certain he’s dead?’

‘He was shot at point blank range with five bullets,’ Boss Olgarv replies.

‘Nevertheless, take no chances,’ the Great Bear says. ‘Send him a death dream.’

Tereza’s magic box …

Tereza doesn’t have the Great Bear’s power; hers is of a different sort. Whereas he commands a great army of followers, Tereza presides over a small circle of artists. But thankfully a few scientists exist at the outer reaches of this circle. It’s to one of these that she now turns in her hour of need.

The scientist is happy to help Tereza because as well as being a scientist, he’s also a man, and as we’ve seen, Tereza has a certain influence over men. The operation of the scientist’s ‘box’ requires only a brief explanation. Tereza carries it away, along with various electrodes, cables and plug-in things.

She stands before Hank with the ‘box’.

‘This is a “box”,’ Tereza announces.

Hank’s rapture is now stronger than a hurricane. He looks at the ‘box’ with wonder, like a child lost in a forest who stumbles upon a house made of chocolate with a Cola pond.

‘And this is how it works,’ Tereza continues. ‘As you can see, there are three screens. The first is red: when illuminated, it shows the word “lie”. The middle is orange; it displays “cliché”. Finally, green. If this flashes you’ll see the word “truth”.’

Cables, colours, screens, machines, Hank thinks. A jungle of suggestive possibilities.

‘I’m attaching an electrode to your head,’ continues Tereza. ‘This monitors your brain and classifies your answers lie, cliché or true. For a lie, the “box” lowers you six inches. For a cliché, three inches. For the truth, nothing. The “box” sends a signal to the hoist here and it makes the adjustments.’

Tereza takes a cable attached to the side of the ‘box’ and plugs it into a socket in the motorised builder’s hoist.

‘At every lie or cliché, a klaxon sounds,’ Tereza adds.

‘A game?’ Hank asks, a note of caution creeping into his voice.

‘Yes, a game,’ Tereza replies. ‘But not for two players. I’ve invited some of your friends – or should I say family? – to join us.’

Tereza presses the ‘open’ button on the control operating the roller shutter that separates the studio from the garage.

There’s a thunderous roar like a sudden surge of water, then a cacophony of oinking, snorting and squealing as a dozen famished would-be aviators stampede into the studio. Their snouts swivel like homing torpedoes to the smell they detect emanating from Hank’s genitals.

Hank screams the scream of a man falling from a mountain face to certain death. Spittle flecks his mouth. His chest palpitates out of control. He writhes like a lunatic in a straitjacket, which is now what he is.

‘For the love of God, Tereza!’ he shrieks. And Shit TV’s audience spikes to a new high.

Birds and a body …

The invisible voice can’t understand all this fuss about death. This may be because he was never alive. But this, he feels, is beside the point. After Tomas is shot, the doctor checks his pulse. If it’s obvious to everyone that he’s dead, the invisible voice thinks, why bother?

The buzzard and the vulture flap over to the corpse to perform their grisly duties. The bobbing of their necks disguises their surreptitious sniffs at the cadaver. The initial verdict isn’t good. Tomas had been scrupulous in his preparations. Dying clean may have eased Tomas’s passage but it does nothing for the appetite of his undertakers. They like their flesh ripe. They’ll have to wait.

The firing squad shuffles out of the courtyard, duty discharged. After all the preparation, conscience searching and drama of the moment, that’s it. One shot in the morning air and then off to lunch and polishing their boots.

Judge Reynard thanks the squad, fixing each with a stare, and then, head down, departs the set of Shit TV’s latest show.

The crowd outside greets the hearse bearing Tomas’s corpse with wolf whistles and shouts. They bang angrily on its side shouting insults. Again, the invisible voice is surprised. What do the crowd hope to achieve by this behaviour? For Tomas to hear them and feel contrite? It seems to the invisible voice that the crowd wishes to break open the hearse and desecrate the corpse. Why is it that vengeful crowds in history behave in this way? After someone has died, is it necessary to kill them again?

The buzzard and the vulture pull the zip tight on Tomas’s bodybag. The sun is full in the sky, the heat shimmering off the ground. The windows of the hearse are shut against would-be avengers and even in the early-twenty-first century the corpse of an executed criminal isn’t provided with air conditioning. All in all, these are perfect conditions for meat to tenderise.

The hearse arrives at the mortuary and the birds trolley the corpse to a room of rest enthusiastically.

The invisible voice notes that no arrangements have been made for the corpse’s interment. Judge Reynard, an impeccable overseer of every detail, seems to have neglected this one. Given that the point of funerals is to comfort the living rather than remember the dead, why should Tomas get one? Funerals only happen when people are sad.

All this is good news for the undertakers. They close the door with a satisfying click. This induces an uncontrollable bout of neck bobbing. They clash beaks and heads in their excitement, but they’re oblivious to the pain. In a frenzy, they begin a kind of dance, flapping their scrawny wings and jumping up and down on the spot. Tomas, the provider of lethal morality lessons, is laid out in a room of peace, excoriated by two out-of-control carrion eaters.

The vulture eventually calms down and pulls a bundle wrapped in cloth from underneath the trolley. His wings sag under its weight and the buzzard flaps over to help. They lay the bundle down on the table and pull the cord which binds it. The cloth unravels and the buzzard’s eyes bulge at the array of saws, knives, hatchets and other jagged-edged things. This is a surgeon’s kit from a bygone age. But the buzzard and vulture don’t have a medical use in mind.

A fight ensues, as it always does with these birds, over a particularly vicious-looking saw. It resembles a permanently smiling shark and probably has its bite as well. After a scuffle, a compromise is reached. The vulture has the saw, the buzzard a machete which would make a Gurkha proud.

The invisible voice watches these proceedings with rising alarm. Of all his observations today, the one that is causing him the greatest concern is that Tomas isn’t dead. But he soon will be.

Drowned in a Russian soup …

We dream in life. Well, why can’t we dream in death?

In his death dream, Tomas is walking along a seaside promenade on a fine summer’s day when a black limousine screams to a halt next to him on the curb. Four burly Russians get out. They are bald, unshaven, with hands like joints of ham. They wear sunglasses and shout loud Russian words to frighten Tomas and encourage each other. He is dragged into the back of the limousine, which makes a screeching U-turn and barrels out of the city.

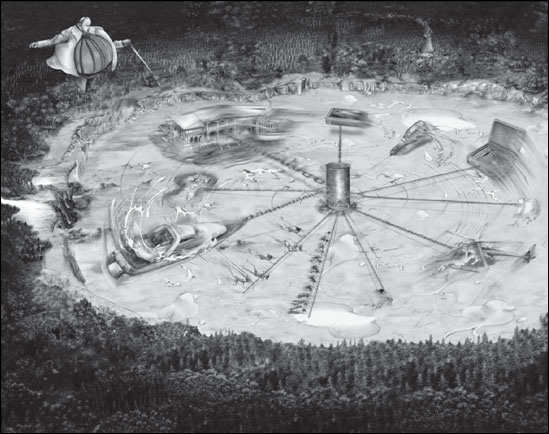

Eventually they stop in a wooded area some distance behind the city. Tomas is roughly manhandled out of the car. Before him is a large pit, about a mile in diameter and fifty feet deep, which has been dug in a forest clearing. Tomas is thrown into the pit, tethered to a post on its outer rim like an animal.

From his captive position, Tomas sees an enormous metal rod in the middle of the pit. It rises about a hundred feet into the air. Welded on to its surface is a series of bulky hoops from which massive chains run off into the pit. Looking up from his post, Tomas also sees a large concrete structure, which he guesses to be some sort of power station.

Dozens of figures and objects now emerge from the forest and the pit becomes a beehive of activity. This is directed, it seems, by a fat earmuff-wearing Russian with what looks like a detachable stomach, who is standing on the pit’s far side. It is Boss Olgarv.

Tomas watches as the figures and objects, all of which appear to be the fat Russian’s possessions, are attached to the chains. The larger objects include a seaside villa, a helicopter, a jet and a yacht. Smaller objects fixed to the ends of the chains include a bottle of champagne, a sachet of cocaine, a plasma TV, a jacuzzi and a cigar humidor.

Tomas then sees various figures herded into the pit. A blonde trolleying her breasts in front of her, presumably the fat Russian’s wife, is attached to a chain. Next to her are tethered half a dozen prostitutes. Beside them is a football team, alongside them some hitmen. Tomas guesses these unfortunates to be the fat Russian’s human possessions.

A whistle sounds, there’s a humming noise and the ground begins to vibrate. The power station has been activated and energy is surging through a subterranean cable connected to the metal rod.

Slowly, with a groan, it begins to rotate. The massive metal chains holding the people and objects become taut. At first, nothing happens. But as the power surges, the villa, jet and yacht begin to inch along the ground, dragged by the metal chains.

The humans begin a slow walk but the pace soon quickens to a jog as the power is increased and the rod rotates at a faster speed. Within minutes only the football players, who are fit, keep pace with the rotating chains. Eventually even their stamina fails and all the humans and objects are flying around the whirling rod with an incredible velocity.

The fat Russian gives a signal and the power is set to maximum. Tomas covers his ears. The humming is now a single screeching high-pitched note. It’s no longer possible to discern champagne bottle, helicopter, prostitute, wife or yacht. It’s all just a whirling blur.

Tomas looks down at his feet and notices a yellow liquid collecting in the pit. Within minutes it’s up to his waist. For reasons he can’t understand, the swirling rod is turning the fat Russian’s possessions into a yellow soup. But his incomprehension doesn’t matter, because very soon he’ll be drowned.

The soup rises to his neck, then his mouth. Tomas shuts it against the liquid and tilts his head back, raising his mouth and nose to give himself precious extra breathing time. He uncovers his ears to free his hands in his struggle against the soup. Instantly his eardrums perforate. Blood trickles down his face and splashes red in the yellow liquid. The rod is now spinning at a speed beyond sound. Tomas screams, feeling his head about to explode. And just as the soup reaches his nose, a cold shock hits his face.

Hank 1: Torture, truffles and truth …

If only it were possible to scream your way out of trouble. Despite a bellicose performance, Hank remains suspended naked in a harness, four feet up in the air.

Tereza has calculated, with the help of the pig farmer, that the maximum jump of a ravenous truffle-mad pig is three feet. Just twelve inches separate Hank from an irreversible sex change followed by an excruciating death.

Although Tereza is the architect of Hank’s predicament she remains courteous and reminds him of the rules.

‘Just remember,’ she says. ‘It’s six inches for a lie, three for a cliché and nothing for the truth. There are six questions in all.’

This information, although edifying for Hank, is of no interest to the demented pigs, who continue their leaps unaffected by considerations of truth, cliché or lie. They slather and snarl and attempt to frustrate each other’s jumps with nasty bites and butts.

A third party witnessing this scene – the invisible voice? – might speculate whether Hank wants to be put out of his misery. But no death wish can be considered let alone granted, because Tereza hasn’t yet had her game.

‘The first question is why did you become a banker?’

Hank catches his breath. ‘Money,’ he gasps. ‘It’s an obsession. We see magazine covers – CEOs and billionaires – and we want to be like them. To be a banker. It’s about status and wealth. There’s no thought beyond that.’

The green light displays. A good start.

‘And why do you want money?’ Tereza asks.

‘For security for me and my family. Money gives you freedom and …’

The klaxon gives a resounding blast and jolts Hank down nine inches. The lie and cliché screens flash red and orange. The pigs sense that their truffle is at last on the move and redouble their efforts. Tereza stands by impassively.

Hank gives an insane shriek. Just three inches to go. ‘OK!’ he screams. ‘There’s no fucking plan, no big idea. It’s just about money. We’re crazed by it. Our bonuses at Christmas. We just want it – holidays, second homes, first-class flights, stuff. To show off. To have. It’s that simple. No charities. No higher calling driving us on. Just stuffing our mouths.’

Hank controls his breathing. He’s close to hyperventilating.

‘Question three,’ says Tereza, ‘do bankers give enough away?’

‘Are you fucking joking?’ replies Hank. He’s flying now. ‘We fucking give nothing, or only an infinitesimal amount.’

Tereza’s impressed by the long word given the circumstances. Perhaps the next version of the ‘box’ should include a mode which moves torturees up three inches to reward the use of a five-syllable word.

‘Yes, there are parties and events,’ he continues. ‘But it’s fig-leaf giving. Conscience relief. A fraction of what we earn. More an excuse to get together and impress.’

The green light flashes. Three questions to go.

‘What do you think about big payoffs?’ Tereza asks.

‘They’re fucking great,’ Hank laughs. Laughter, like tears, in the face of emasculation. ‘You’re the CEO. You lose the bank $50 billion. It’s time to go. Here’s $100 million. And a pat on the back. Good chap.’

Four down. Two to go.

‘How do you treat women?’

In cricket there’s a concept called a daisy cutter. It’s a way of bowling the ball by rolling it slowly along the ground. It’s used for children new to the game to break them into connecting bat with ball. Daisy cutters are impossible to miss. And Tereza’s just bowled one at Hank.

‘At first, respectfully,’ he says. ‘Can you believe I got married with the best intentions? But drift sets in. When you’re working like a maniac you lose perspective. You forget, if you ever knew, your priorities. You start making excuses to work. All-important life-and-death work. You know what I do on the beach with my kids? I fucking BlackBerry.’

Hank’s on a roll. There are no rules for a preamble to a full confession, which is what Tereza and, more importantly, the ‘box’ now require.

‘There are a lot of divorces. But even more visits to hookers and strip bars, especially when travelling. What the fuck do you expect? You spend your life in a madhouse, working like a dog, worshipping money. And somehow your home life’s meant to be normal?’

The ‘box’ flashes a resounding green. Hank hangs his head, his energy spent. It’s as if he can’t go on.

‘Take your time over the last one,’ says Tereza. ‘The “box” can tell if anything’s left out. So make your answer full.’

Tereza pauses to let what she’s said sink in.

‘Apart from now, what’s the most frightening experience you’ve had in your life?’ she asks.

The sobering effect of ice…

The invisible voice may only be a voice, and invisible at that, but he knows a crisis when he sees one. In a flash he’s before his maker.

‘Emergency!’ he says. ‘I need a fifty-foot club-wielding monster to smash into a mortuary.’

His maker looks up from behind his desk with the bored expression of a till person shouting an unenthusiastic ‘next’.

‘OK,’ pleads the invisible voice. ‘A giant will do.’

‘All that’s left is a foot in mouth, a blind eye and a visible hand,’ says his maker.

Had the invisible voice a heart, it would sink.

‘I’ll take the hand,’ he says. Moments later, he materialises with the visible hand at the seaside cafe where Tereza made her confession to Tomas.

‘I’ll do the talking,’ the invisible voice says. ‘You back me up.’ The visible hand raises his thumb.

The waiters are, as usual, bunched together at the serving counter ignoring the customers.

‘I’m the ghost of the outstretched hand for tips,’ intones the invisible voice. ‘Do me a service or I’ll forever haunt this cafe.’ The visible hand hovers in the air, palm outstretched before the waiters.

‘Go on,’ urges the invisible voice. The visible hand floats off towards the diners. His intent is clear. He’s scavenging for tips.

‘Stop!’ shouts the headwaiter. ‘Your service. Name it.’

‘A bucket of ice. Immediately,’ the invisible voice replies.

Within moments this is produced. The voice and hand materialise outside the door of Tomas’s room of rest. ‘OK, knock,’ the invisible voice commands.

They hear a scuffle the other side of the door. The carrion eaters have been quarrelling about which joint to carve first. A compromise is imminent; the vulture’s smiling saw is poised over Tomas’s thigh.

‘Attention, undertakers,’ says the invisible voice. ‘Your assistance is required. An experiment in the temporal displacement of matter has had mixed results.’

‘We’re busy,’ says the buzzard.

‘Hear me out,’ the disembodied voice replies and the visible hand gives the door another rap. ‘We have successfully transported the entire animal population of the Serengeti to the space outside this building. This is the biggest collection of wild animals in the world.’

‘So?’ says the vulture.

‘Unfortunately, there was a fault with the matter-transfer technology,’ the invisible voice replies.

‘And?’ says the buzzard.

‘All the livestock were killed in transit. There are a million dead animals requiring your attention.’

The buzzard and vulture barrel out of the room faster than Boss Olgarv’s swirling rod.

‘Quick,’ says the invisible voice, and seconds later a bucket of ice is poured over the corpse’s head.

The second Messiah …

News of Tomas’s resurrection knocks the socialite with underpants off the front page. In an attempt to recapture lost ground, she strips naked and jumps up and down shouting, ‘Look at me! Look at me!’ Alas, she’s been poorly advised: when nothing is held back, what’s left to see? The press pack now pick up the scent of the new story, which they chase with yelps and cries without so much as a sideways glance at her bouncing breasts.

This all goes to prove the old adage ‘a good resurrection will always make the front page’. (Or, is it, in fact, a new adage? As far as the press dogs can work out, there’s only ever been one resurrection before, also of a man condemned to death, but at a time when there were no front pages.) From the remotest Chinese paddy field to the US President’s Oval Office, Tomas’s resurrection becomes the biggest media event in world history.

Judge Reynard takes charge and Tomas is transported back to the military base, the place of his execution. There are medical checks, interrogations and psychohypnotic sessions. But what’s the point? The truth is clear. Tomas has returned from the dead.

This simple fact is disconcerting to those who shot him. Soldiers are accustomed to straight lines, not supernatural events. If you’re shot, you should remain so. To be resurrected is like disobeying an order – unthinkable. The military commander says as much and suggests re-convening the firing squad.

‘Is that wise, commander?’ says the judge. ‘In the few thousand years of man’s civilisation only two people have risen from the dead: Jesus Christ and now Tomas. And you wish to shoot him?’

The judge must consult his senior judicial colleagues immediately to discuss the situation but he’s apprehensive about leaving the commander in charge. He takes a fateful but necessary decision.

‘While I’m away, commander,’ he says, ‘you’re to guard Tomas with your life and follow his instructions in all things. I’m sure you understand.’

The commander salutes and stands to attention. For him, an order is no sooner given than it’s obeyed.

Tomas decides to use his new-found powers to test his theory about intelligence and obedience.

‘Commander,’ he says, ‘the battalion will parade at six o’clock in the courtyard.’

Again the commander stands to attention.

‘Dressed as ballerinas.’

The commander’s face remains impassive without a flicker of concern or surprise.

‘The tutus are to be pink. You, of course, are the prima ballerina, so yours will be white and especially ruffled. I’ll give further instruction thereafter.’

Tomas has long held the view that it’s easier to take orders if you’re stupid. Those encumbered with an education tend to be more questioning when told what to do, especially if the orders are venal and pointless – for example, killing other people. Their hearts are just not in it. Others not so burdened do as they’re told and get on with the killing. Of course the corollary is that order takers tend to be braver than their more cerebral counterparts. Naturally, there are exceptions to the rule, but in general only the stupidly brave will follow an order to charge a machine-gun nest in broad daylight across a minefield.

The battalion parades at the appointed hour in the uniform specified.

‘Half the battalion,’ announces Tomas, ‘are female swans. You stand to the left. The remainder are swan catchers. You move to the right.’

The battalion ranks shuffle in obedience.

‘On my command the female swans will flutter their arms and leap into the air. The swan catchers will give chase with exaggerated dramatic gestures. Commander, you will pirouette around the courtyard, holding the back of your wrist to your forehead as if a tragedy is unfolding before you.’

The soldiers adopt the preparatory ballerina position, heels together with one foot pointing outwards, arms held in front with hands curved.

Tomas gives the command. ‘Swans, leap!’

These are battle-hardened soldiers, trained in the deserts of North Africa. To see them leaping and pirouetting, one could easily mistake them for an enthusiastic amateur ballet school, all scoring ‘A’ for effort.

After the swans have been caught and the commander has given a bravura performance as the vaulting tragic muse, the battalion is dismissed to its barracks. Tomas is left to ruminate on the three points that have defined this historic day.

First, he’s alive. How and why he has no idea. Having provided his morality lessons he was caught and in a way tried. Sentenced to death, he faced his executioners with Tereza’s beautiful face in mind. He felt nothing but a swirling sensation in his veins, followed by sleep.

Second, the theory’s right. The stupid do follow orders and he has the additional satisfaction that yesterday’s executioners are today’s leaping pink swans.

And third, he now has a battalion of the stupidly brave at his command.

Hank 2: Defining a man’s worth …

‘So what’s it going to be?’ Tereza asks. ‘You’re on a plane struck by lightning? Lost in a forest as a child? Ruptured your appendix and almost die?’

Despite the symphony of oinks and squealing, Hank’s breathing is now calm. His words when they come are clear and measured. The condemned man on the scaffold making his valedictory speech, untroubled by thoughts of hope or reprieve.

‘The night before the big day,’ Hank starts, ‘sleep is, of course, impossible. But I’d settle for a sleepless night. Instead I sweat like a sick child with a fever; cheeks burning, hair wet.

‘In the early hours I drift off for a few minutes, the sort of sleep that comes from exhaustion. I have the nightmare which first came to me when I was ill as a child. I’m orbiting the moon in a spaceship, unable to return to earth. I go round and round, forever trapped in space. I wake up horrified that this dream keeps returning.

‘I shower off the sweat and the nightmare but there’s no way I can eat breakfast. My stomach is a forest of knots. The thought of food is nauseating, laughable.

‘I dress with a crisis of indecision over which tie to wear. Which lucky tie? I choose and tie the knot. My neck swells and I pull at my shirt collar but it makes no difference.

‘At work, it’s like no other day. It’s as if you’re on a beach holiday when one day, for no reason, it snows. We all know each other but no one makes eye contact. It’s too dangerous. It would give too much away.

‘Chuck’s called up first. When he returns I pretend not to look but I can’t help sneaking a glimpse. There’s a half smile on his face, which tells me nothing. Or maybe everything? Or nothing and everything? Who the fuck knows? Chuck sits at his desk and makes a silent phone call to his wife.

‘A comic thought pops into my head. Shit TV should screen a series of hushed-voice phone calls, everything people don’t want others to hear: whispered secrets; doleful confessions; bad news; excruciating revelations; embarrassing results. It would achieve top ratings. People love other people’s pain. The misfortune of others is even more satisfying than your own success.

‘I know I’m going to be called up sometime after lunch. But even though I’ve trained for it, like a sky diver making a jump, I’m not ready. “It’s your turn, Hank. Secure your parachute. Jump!” But I’m not jumping. I’m going up in a lift.

‘The lift door closes with a finality that says: “This could be your last journey up. Or maybe there’ll be more. You’ll know in five minutes.”

‘ “Go straight in, Hank,” says my boss’s secretary. I put my hand on the door handle. I breathe in and out hard. Whatever happens I mustn’t show how I feel. This is it. I push the door and go in.

‘ “Hank, come in,” says my boss. “Sit down,” and then, “Sit down,” again. That’s two “Sit downs”. Is that as in, “Relax, it’s all OK”? Or as in, “I’ve got some bad news for you, you’d better sit down (twice)”? I sit down.

‘ “It’s been a great year,” says my boss. That’s an OK start but the words “for you” added at the end would’ve been better. The first sentence tells you a lot. Maybe everything. I adjust my expectations to my upper-middle level.

‘ “Your bonus is $3,000,000.” That’s it. A lightning flash. No preamble beyond the introductory five-word banality. Then three words followed by a number which defines my worth as a man.

‘I make a rapid calculation as my boss makes some ceremonial pleasantries. $3,000,000, less forty per cent tax leaves $1,800,000, divided by two for sterling leaves £900,000 net. I wanted £1,000,000 but it’s not bad. And the bank’s been clever. I’m fed but left hungry for more.

‘My boss wraps up and I don’t display a flicker of emotion. I say “thank you”, shake hands and leave the room.

‘I exhale and close my eyes, leaning against the lift on my way down. The show’s over. The walls of my world remain intact. But I still maintain the outer pretence. It’s my turn to make a half-smile and silent phone call. I can see without looking that the office is watching. They’d pay $1,000 each to hear the secret I whisper to my wife.

‘I now relax and think about my £900,000. It’s in my account already. One thought warms me like a nip of brandy on a cold day. My boss could’ve said, “Your bonus is $1,000,000.” Finito. Game over. Although I’d dress up my job at a new bank, everyone would know. And then it would be downhill all the way; my misfortune providing pleasure to others.’

Tereza looks at the ‘box’. The electrode connected to Hank’s head is still in place. Why the delay? Seconds later a light flashes. It’s green.

The dangers of deity…

Tomasmania is spreading,’ reports Shit TV’s news bulletin, ‘and all things French are now in fashion. We’re hearing of ranchers in Australia demanding delicate sauces with their dinners and Kazakhstani miners scenting their fingertips with Eau pour L’Homme. After two millennia, the new Messiah has arrived. And he’s French.

‘This just in,’ the bulletin continues. The screen flashes to a picture of the White House lawn. It’s thronged with dignitaries, officials and the press pack in the usual sombre dress of those attending a president. A trumpet sounds, but it’s not the blast of modern brass. It has the ring of something else – eighteenth-century France. The White House doors fly open and the American President appears, dressed as Louis XIV. He’s wearing full court dress of white stockings, billowing skirt and a fabulous brocade jacket. His face is whitened, with rouge spots on each cheek, and he wears a gigantic wig, supported from behind by a servant with a stick. He walks in high-heeled shoes with silver buckles with the decorum of the Sun King himself, making exaggerated gestures. When the camera pans in, he produces a handkerchief from a ruffled sleeve and waves it at the audience.

‘The American President has reacted to the craze for all things French and given it a twist. In reality singing shows it’s called “making the song your own”. People love it.’

Tomas arrives in Paris and, with the help of the judge and his battalion, commandeers a hotel in the Place Vendôme. Where previously a uniformed doorman would greet visitors with a raised hat, Tomas’s battalion now guards the hotel with automatic weapons. The soldiers swarm the vicinity, dressed in military fatigues with commemorative pink armbands, to ensure Tomas’s total security. Again one might consider the wheel of fortune’s rapid turn. From executioners to pink ballerinas and now loyal-unto-death bodyguards. A soldier’s heart, once given, is unbiddable. And imagine the prestige of guarding the new Messiah.

Despite the need for security, Tomas slips out of the hotel in disguise to meet Tereza in the Tuilleries gardens nearby. As ever, his heart skips when he sees her. The northern light accentuates the golden aura, which is what Tomas most associates with Tereza. Her simple beauty takes his breath away.

‘Well, I was shot, almost eaten and drowned,’ Tomas says, as lightly as someone might say, ‘I’ve been shopping and had a coffee.’ ‘How about you?’

Tereza touches Tomas’s face. He’s definitely real. But it would be a cliché to interrogate him as the rest of the world is now doing. She’s always made a virtue of not following the crowd.

‘Hank’s a media star,’ she says. ‘He had an epiphany and confessed the sins of his profession, which our friends at Shit TV happened to televise. And Pierre, whom I met at your trial, has become a celebrated journalist, after having discovered that something is brewing in Russia.’

From golden to avenging angel. He’s delighted.

‘Tomas, you need help with what’s happened,’ she continues, ‘Pierre can ask questions. He’s trained in these matters. I’ve asked him to join us.’

As they wait for him to arrive, a stranger approaches carrying an umbrella. ‘Odd,’ thinks Tomas, ‘on a sunny day.’ Something in the back of his mind triggers a memory; he recognises the stranger’s face but the rest of him looks so … thin.

Boss Olgarv, minus his detachable stomach, is now parallel with them. As he passes, he jabs the umbrella at Tomas, who jumps out of the way. ‘Excuse me,’ the Russian says.

Tomas and Tereza look at each other, bemused. They expect him to pass on but instead he turns and jabs at Tomas again. ‘Hey!’ shouts Tomas, once more avoiding the thrust.

‘Excuse me,’ Boss Olgarv repeats.

‘Watch what you’re doing,’ says Tomas. But the Russian ignores him and lunges again. This time, he only just misses and Tomas has no choice but to take off at a run.

Tereza watches Tomas being chased around the fountains of the Tuilleries gardens by a strange Russian jabbing an umbrella at him with an apologetic ‘Excuse me’ after each thrust. The stranger’s intention clearly isn’t benign; he appears to be a special type of murderer, bizarrely asking for forgiveness after each failed attempt. Although an assassin by profession, perhaps he’s polite by nature? Or maybe it’s part of his trade? For politeness disarms and can be dangerous.

As Pierre arrives in the Tuilleries gardens, a cylindrical object propped up against a wall catches his eye. It’s Boss Olgarv’s stomach. He stops to investigate and discovers a compartment containing two dart racks – ‘truth’ and ‘death’. There is a ‘death’ dart missing. Presumably, it is attached to Boss Olgarv’s umbrella. Pierre takes two ‘truth’ darts and hides behind the wall.

Eventually Tomas, who’s fit, disappears around a corner and Boss Olgarv, exhausted, comes to retrieve his stomach. As he bends over to clip it in place Pierre sticks a truth dart in his thigh. Once again Boss Olgarv provides material for a story.

Later Pierre meets Tomas and Tereza. Pierre nods awkwardly, unsure of the protocol on meeting a possible deity. He gives Tomas the second ‘truth’ dart. ‘One of these marked “death” was meant for you,’ Pierre says.

‘Thank you,’ says Tomas, putting the dart in his pocket. ‘One day I’ll use it. But for now I understand you intend to ask some questions on my behalf. Please, if I can be of any help … ’

‘I will of course interrogate your executioners in detail,’ Pierre replies, ‘but for the moment I’ll only trouble you with a few questions, if I may. Do you believe in miracles?’

‘I don’t,’ Tomas replies. ‘And I can’t explain what’s happened. But I do believe in the miracle of ideas. Maybe my corpse was somehow indoctrinated by my beliefs and came back to life.’

Pierre considers the proposition of an ideology so strong that it transcends death.

‘I can assure you of one thing,’ Pierre says, ‘everyone wants it to be a miracle. The press for their headlines; Shit TV so that they can devise some perverse take on it. The truth is incidental.’

As Tomas ruminates on man’s capacity for self-delusion, Pierre asks, ‘The incident in the gardens – has anything else strange happened?’

A light goes on in Tomas’s head. The umbrella assassin is the yacht-owning Russian who was also in his soup dream.

‘This bears close investigation,’ says Pierre. ‘Whether you’re the second Messiah or not, one thing’s for sure. The Russians are trying to kill you.’

A beautiful game …

Boss Olgarv is depressed. Pierre’s second article, ‘The Great Bear and the Hawk’, leaves him in need of vodka and oblivion.

Why is the Russian Great Bear such a great friend of the Iranian Hawk’s? Is it geographical proximity? Why do these predatory animals hunt together?

We know that the game of international détente is played according to certain rules. For example, you never say what you feel and always calculate what you do. The Great Bear and the Hawk dispense with such niceties. If an individual needs to be eliminated, it is done. Hang the consequences. If a country deserves to be annihilated, say it. Invaded? Do it. To hell with everyone else.

Sharing such martial qualities, it is unsurprising that these allies have established a physical link. I can now reveal that a pipeline exists between these nations, hidden beneath vast deserts and windswept tundra. Its purpose? To carry oil.

The reason for the Great Bear’s indulgence of the Hawk’s flights of fancy is now clear. It’s being fed. While it prefers honey, oil can buy a lot of this.

As we know, the Russian beast is currently flooding the West with sticky stuff; soon we’ll all be stuck. The Hawk’s pipeline provides an invaluable resource. But what does he receive in return?

Technology, information, knowhow; all with nuclear potential. And the result of a launch against the West? A triumph for the Hawk, disaster for the West and of little consequence to the Great Bear. So let the Hawk have his toys.

Where does this end? Even the biggest honey reservoir will eventually run dry, and the Great Bear needs an ocean to execute his final plan. Read on as we attempt to discover how far and deep the pipeline runs.

Boss Olgarv decides to throw a party to cheer himself up and invites his football team.

But this isn’t his only largesse. ‘Kick a ball around a field. Here’s £100,000 per week.’ Imagine the tears of outrage from the player offered only £95,000. ‘An insult!’ he cries.

Still, perhaps this money mountain creates some greater good? If mansions, cars and diamond ear studs are categorised as such. But the footballer’s ultimate trophy is, of course, his wife. In acquiring one, the strict rules of cliché apply: lack of singing talent, trolley-borne breasts and vulgar wedding arrangements are the most important. Detailed sub-rules govern these. Nuptials must be immortalised in the pages of a sponsoring pressdog publication. What girl doesn’t dream of a six-foot camera lens inches from her nose at the moment she says, ‘I do’?

But the rules don’t stop there. Miles of forest must be destroyed in the cause of reporting – in photographs for those who can’t read – the continuing alliance of two brilliant minds in our glorious culture.

Back to the party, which, like football, is a game of two halves.

The rules for the first are easy and obvious. To get drunk. This is performed as speedily as a pass down the field. That accomplished, the team trots on to the pitch for the second half. At this particular party, it plays flawlessly.

‘You up for it?’ says a star player to his team mate. ‘If you’re game?’ comes the reply. And then together, ‘Come on lads.’

They’re sitting with four of their team mates at a table with three girls. One is young – just fifteen – and exquisite. Long black hair framing an oval face; rosebud mouth; soft skin; the lithe body of a dancer: all the prerequisites for a good time. She sits shyly with her eyes cast down, hands on her lap. The star player gives her a cocktail containing his own special ingredient.

‘Excuse me, ladies,’ says the star player and grabs the fifteen-year-old by the hand. ‘You’re gorgeous,’ he says, champagne breath besmirching her young face. But she doesn’t notice the smell. His cocktail is having an instantaneous effect.

The squad moves upstairs with shouts and laughter, carrying the girl in its wake like flotsam. ‘In here, darling,’ says the squad leader. ‘You going to perform for the boys?’ She laughs, her head rolling like a rag doll’s.

They’re in a plush room above the main drinking saloon, dimly lit with deep comfortable sofas. There’s a drinks bar stacked with champagne and vodka on ice. The squad charge the bar, like a ball on the pitch, and decapitate several bottles.

‘Down in one, sweetheart,’ the star player shouts. The teenager obliges, to cat calls and applause. ‘Get ’em out! Get ’em out! Get ’em out!’ a chorus starts from the terrace of the big sofa, where the footballers are now encamped.

She wobbles to her feet, her world beginning to fade. She’s wearing a slip of a black dress. She turns her back to the terrace. This triggers an eruption of shouts and whistles. She slips down her shoulder straps and undoes her bra. When she turns round, she covers her breasts with her hands before suddenly shooting her arms into the air like a fan when a goal is scored.

‘Weeehay!’ shouts the squad and then, ‘Here we go! Here we go! Here we go!’ The star player’s, ‘Come on love,’ is drowned out by his team mates’ chant, ‘All the way! All the way! All the way!’

The girl is centre stage. Six sets of football eyes ravish her. She’s the most desirable object on earth. Except she’s not on earth, she’s floating above it. Who would believe it?

She lets the black dress slip to the floor. Without decorum, she strips off her pants and stands hands on hips, legs apart, swaying slightly.

The dam bursts. The star player scoops her up and sweeps her on to the sofa. Whilst performing this manoeuvre he loosens his trousers. By the time her back hits the cushions he has penetrated her.

The terrace opposite explodes. This is it, their very own game. ‘Go on, give it to her!’ ‘Take one for the team!’ ‘Let her have it!’ Within minutes the star player is satiated, his semen fouling her adolescent body. He gestures to another player to takes his place.

The girl groans. It’s all just lights and colours now. She hardly notices as she’s hauled up and turned over, her chin resting on the sofa’s arm. As the second member takes his turn, the star player positions a third before her, as if setting up a penalty ball. A chant of, ‘Pass it on! Pass it on! Pass it on!’ echoes in the air. And then an ear-splitting, ‘Weeehay!’ as she begins to pleasure the third member simultaneously.

Now it’s more than a game. The girl’s no longer just a ball being kicked around. She’s a cipher for something else, just as the players’ machismo shouts and yells disguise a darker desire; one that would shock adoring fans. For the players’ eyes now fix on each other’s moving parts. By moonlight the vampire awakes. Drunk in the dark, our heroes taste an unspoken pleasure.

The star player now takes up position behind his team mate as if supporting him in the goal mouth. He puts his hands on his mate’s hips and rocks him in and out, assisting his gratification. ‘Yeah, Yeah, Yeah,’ he groans. Suddenly he bends him forwards and, with a tap of his foot, opens his legs. His team mate continues his rhythmic rocking as if being touched in this way is normal. Moments later his tempo is thrown, as the star player penetrates him from behind.

Rapidly the rest of the squad form up, as if executing a manoeuvre on pitch. A player penetrates the star from behind, offering himself in turn to the next member until a pulsing snake takes shape around the sofa, each man moving to a synchronised beat. The fifteen-year-old is no longer centre field: soon she’s sent off altogether as the sodomy circle closes. In its dying moments, the game is played in silence, except for deep-throated grunts and groans.

Eventually a collective exhalation of breath, in place of a final whistle, signifies that play is over. The squad zip up with shouts of, ‘We gave it to her good,’ ‘She deserved it,’ and, ‘That’ll teach the dirty bitch.’ They stagger back downstairs, leaving the teenage girl comatose on the sofa. It’s been a beautiful game.

The future of architecture …

Tereza has a surprise for Tomas.

Deities don’t usually sneak out of hotels for surprises; they waft about in clouds doing deitific things. But Tomas is a modern Messiah, and soon they’re in Tereza’s Deux Chevaux on their way to the Bois de Boulogne.

It’s late. Tereza parks in a side road. A few moments later, they’re at the edge of the park. And there’s the surprise. The fairground’s in town. Tereza performs her magic trick and they take their places in the time machine.

‘You choose,’ says Tereza.

Tomas thinks. Oceans of possibilities open before him. The dawn of time? The Stone Age? The Dark Ages? Or maybe the years 3000, 4000 or 5000? He chooses modestly. ‘Paris fifteen years from now.’

‘OK,’ Tereza replies, ‘strap in.’

Tereza presses some buttons and adjusts a lever. The machine begins to hum. There’s a silent clank as the craft slips its mooring and they glide vertically into the air.

The city looks beautiful twinkling in the night. Tomas is in the clouds on a journey through time with the woman he loves.

‘Where to?’ Tereza asks.

‘Another fairground,’ Tomas replies. ‘Euro Disney.’

The craft floats above the centre of Paris, which is identical to the one they left only minutes before. The business district and outskirts, however, have been rebuilt – ugly offices replaced by buildings of the same size but in the Parisian style. The workplace has been ennobled.

As they reach the suburbs, Tomas and Tereza are shocked. Paris, always small by global standards, now stretches for miles in every direction. It looks about the size of Tokyo. Yet all the architecture is in the traditional French style with tree-lined avenues, squares, parks and public places.

‘This can only mean one thing,’ says Tereza.

Tomas looks embarrassed.

They reach their destination. But where’s the magic castle? Has it magicked itself away? On the site of the Haunted House and Space Mountain sits the most beautiful building Tomas and Tereza have ever seen.

The palace is fashioned as a croissant – literally. Most palaces, with their bulky centres and outstretched wings, resemble a croissant to some extent. But this new presidential property has been built as a gigantic replica.

The palace is exquisite. Golden brown, its aura reminds Tomas of Tereza. It falls seamlessly from a high central core to two circling arms with a ribbed exterior. Great curved windows in the roof flood the building with light. A modern Versailles, it makes the original look fussy and old.

In front of the palace, ornamental lawns and fountains fan out on either side of a wide tree-lined boulevard. The craft hovers overhead and Tomas and Tereza gasp at a second wonder.

The boulevard opens on to a space that is dominated by an edifice in the shape of a giant beret. It looks as if it has just been removed from a milliner’s box. The rich, textured roof undulates like the creases of the cap; it is a perfect imitation, a million times the size. Like the croissant palace, curved roof windows punch light into its interior. The console of the time machine identifies the royal blue building as the new Parliament of the United States of Europe.

Tereza pulls the craft into a steep climb. Up ahead, down the boulevard that runs from the beret parliament, stands the most magnificent construction of all. It soars three thousand feet into the clouds like a giant standing on a misty mountain top. The three parts of the building, clove shaped, are balanced around a central opening. The largest clove stands upright, occupying half the space. The second, half the size of the first, slants inwards like a billowing sail; the third, the smallest of the three, protrudes outwards at a precarious angle. The cloves are luminescent grey and look like three sculptures in permanent conversation. Seen together, the true form of this administration building now becomes clear to the time travellers – a giant garlic bulb.

‘This is how architecture should be,’ thinks Tomas. ‘Monumental, light, original, patriotic and with a sense of humour.’

Tomas and Tereza are mesmerised. How can France have risen to such heights?

Tomas is clumsy in his wonder and knocks a lever. Instantly the craft lurches with a back-bending jolt and the travellers see a thousand stars in fast motion. There’s a bang as if they’ve hit some space debris. For a moment Tomas thinks he sees two spherical objects with suction pads on the windscreen.

‘Hang on,’ says Tereza, ‘we can reach our time and place. But I can’t control the landing spot – there’s too much chop. We’ll just have to chance it.’

The craft begins to vibrate and Tomas clutches his arm rest. The turbulence worsens. But something else is making it unstable. Tomas looks at Tereza. As her hands move over the knobs and levers, he detects an unfamiliar shadow across her face. Fear? He closes his eyes.

An intelligent show for intelligent people…

Pierre begins his investigation of Tomas’s Messiahship by trying to locate the vulture and the buzzard. ‘Apparently,’ says a local witness, ‘they’ve been driven demented by the notion of a lost Serengeti.’ Anyway Pierre regards these birds as unreliable witnesses. Would you trust anyone who wanted to eat you?

He then talks to the execution squad of the battalion which Tomas now commands. ‘It’s as you would expect, monsieur,’ the squad’s sergeant explains. ‘We stood in line. The order was given. We’re all expert marksmen. And anyway it was impossible to miss, even if only one rifle had been loaded. We took aim and Tomas was shot, as plain as I’m speaking to you now.’

Next he talks to the smoker in the squad, an uncommunicative man. Perhaps he has been traumatised? Pierre attempts to lighten things up. ‘Were I the author of a satirical novel,’ he says, ‘I could hardly invent anything more ridiculous than the cigarette.’

The soldier carries on smoking.

‘All those little boxes containing sticks with big warning signs – “Death”, “Cancer”, “You will die” – emblazoned on the side. Yet people continue with the habit. It would be the most abstract part of my satire.’

‘I know,’ replies the soldier, ‘but what can I do?’

‘Give up, as I did. I made a promise to do so in return for a good story. With the help of a hypnotherapist it was easy. I’ll give you his number. If you’re able to shoot a man, you can give up smoking.’

Pierre rushes off to a meeting with one of Shit TV’s top stars. His initial good story on the Great Bear and his disturbing plans for the world has mushroomed into several more; consequently Pierre is now a celebrity and Shit TV want him for their own purpose. Although Pierre has no interest in taking part, journalists are taught to be curious.

The star welcomes Pierre in his black and white office. Everything is black and white, even the staff.

‘Hello,’ says the star standing up and flashing a smile. ‘How nice of you to come.’

Pierre clasps both hands to his eyes and screams, blinded by the smile.

When his sight returns, he’s staring point blank at the star’s exposed stomach. His platform shoes raise him four feet into the air; he needs long sticks to walk. He’s wearing a white shirt inside a black jacket – but what’s the point? All the shirt buttons are undone.

The star manoeuvres himself like a stilt walker to a white sofa, where he sits down, propping his sticks against the wall. He pulls the two sides of his shirt still further apart.

‘Forgive my sunglasses,’ says Pierre. ‘My smoking has given me conjunctivitis.’ Protected from the perpetual supernova of the star’s smile, he sits on the black sofa.

‘No problem,’ says the star. ‘I wear sunglasses all the time but mostly at night. We’re interested in you as Paris’s up-and-coming investigative journalist,’ he continues. ‘We’re launching a new show that we believe is worthy of your stunning insights and raw intelligence. It’s a retrospective concept, combining several programmes from the past with a new element. One of the contestants has just fallen out and needs to be replaced. There is, however, a small catch.’

‘It’s kind of you to think of me,’ says Pierre. ‘But I’m not at all sure. What do I have to do?’

‘You’re going to love this. You’re in a jungle with other contestants, where you perform tasks like eating live bugs, swimming in rivers with crocodiles and putting your head down a snake hole.’

‘But that’s moronic,’ Pierre protests.

‘Are you joking?’ replies the star. ‘To eat a plate of worms requires great powers of concentration, stamina and endurance. This is an intelligent show for intelligent people.’

‘Go on,’ says Pierre.

‘While you’re doing these tasks,’ the star continues, pulling his trousers up over his stomach, ‘a delightful TV chef shouts pleasantries at you.’

‘What’s the point of that?’ asks Pierre.

‘It’s to encourage the contestants,’ replies the star. ‘To create positive energy and a happy atmosphere. When your head’s in a viper’s nest, the chef will be shouting “Are you all right? Can I help you?” with a beautiful cadence.’

‘I see,’ says Pierre, ‘but is there any point to the chef? Shouldn’t there be a food element?’

‘No, you don’t understand; food’s irrelevant, like cooking programmes on TV. They’re not about food, they’re about the chef being nice and wonderfully mannered.’

‘So what happens next?’ asks Pierre.

‘OK,’ replies the star, pulling his trousers right up to his armpits. ‘Now picture the scene. All the contestants have done their tasks and are covered in filth. You form a line in the jungle and the chef walks up and down shouting, “I do hope you’re OK,” inches from your face.’

‘Suddenly I appear out of nowhere and referee a singing competition, the rules of which are that you must make as big a fool of yourself as possible. The more clichéd, awful and talentless you are, the better you do. The viewers then vote for someone to take a shot at the top prize, taking delight in the knowledge that the recipient will never be heard of again and spend the rest of his or her life a crushed soul.’

‘And how do you win the top prize?’ asks Pierre.

‘There are two steps,’ replies the star.

‘Which are?’

‘Isn’t step one obvious?’ replies the star. ‘What do you think the delightful TV chef is there for? Eat his shit.’

‘And step two?’ asks Pierre dumfounded.

‘Surely you can guess?’ the star replies, surprised.

‘Eat your own shit?’ suggests Pierre.

‘That’s disgusting!’ says the star. ‘Eat yourself. Not a vital organ, but a toe, finger or slice of flesh. The more you eat – we’re hoping for a leg for a man and a breast for a woman – the bigger the prize. Of course an anaesthetic will be used for the amputation and the body part you choose will be cooked any way you wish by the chef.’

‘So let me get this right,’ says Pierre. ‘I’m to participate in a slug-eating competition in the jungle, overseen by a polite chef, culminating in an abusive game that poses as a singing competition. And if I win I get to eat the chef’s shit, followed by one of my body parts cooked in front of me, with a guarantee that I will be depressed for the rest of my life?’

‘That’s right,’ says the star, pulling his trousers to just below his chin.

‘And what’s the catch ?’ Pierre asks, stupefied by the conversation.

‘Oh – you have to pass yourself off as a teenage girl,’ the star replies.

‘What?’ says Pierre.

‘Yes, the contestant who’s fallen out is an eighteen-year-old soap star, so we need to replace her.’

‘But look at me. I’m an overweight journalist in my mid forties. How could I possibly pass for a teenage soap queen?’ Pierre asks, exasperated.

‘Oh, don’t worry about that,’ says the star. ‘Our audience is intelligent but not that intelligent. Think it over.’

As Pierre leaves the office he hears a yell from the white sofa. It is reported later that the star pulled his trousers over his mouth and asphyxiated himself.

In the dark with something scary …

Sometimes, in the dark, it’s difficult to tell whether you’re alive or dead. If you’re in pain, you’re probably alive – unless hell exists. Otherwise, the trick is to find the nearest light. This provides a beacon of hope until programming can be resumed. For Tomas and Tereza this is a red flash on the dead control panel before them.

There’s no protocol for the evacuation of a crashed time machine; so Tomas and Tereza follow custom and instinct. Although there’s no danger of combustion, the time travellers decraft. Perhaps the problem is best solved standing up.

And it is a problem. For as their eyes adjust to the enveloping gloom they realise that they appear to be trapped. In a tomb.

Action-movie makers like to put the hero in an impossible situation. Just as you think things can’t get worse, the director twists the knife. Suspended on a rope above a ravine, the hero looks down. What does he see? Crocodiles!

But Tomas and Tereza can’t see, they can only hear. The sound chills their bones. It is the squelch of tentacles on a marble floor.

Moonbeams stream in through windows beneath a dome. Tomas puts a protective arm around Tereza but neither the illumination nor the embrace helps. The sound is getting louder and coming closer.

‘Who’s there?’ Tomas’s voice rings in the air.

Although a possible deity, Tomas still has human frailties. The question is as futile for him as it is helpful to the approaching menace. He has now provided his coordinates in the dark.

Tereza tightens her hold on Tomas. The squelching stops and they inch around the side of the craft. The moon comes out fully, flooding their sepulchral surroundings. There before them, illuminated by a beam, is the squelch maker. It’s tall, round and looking at them.

‘Shit,’ mutters the second Messiah.Tomas’s deitific word hangs in the air. The Alien squelches a step forward and smiles. This only helps a little: is the human smile recognised as a sign of friendship across the Galaxy? For all Tomas knows, the alien equivalent is a prelude to a ray-gun attack.

Tomas shows his mettle as a man, if not a deity, and approaches the Alien.

The Alien is seven feet tall to Tomas’s six and is entirely round. Round head, round trunk, round arms, round legs. His eyes are two big spheres, which blink continuously like the owl’s at Tomas’s trial; his arms, with their three-fingered hands, stretch down to his round knees. Circular suction pads at the end of the spherical feet that Tomas had noticed on the craft’s screen account for the squelching sound. The Alien, clad in a silver suit that might be considered fashionable on earth, now raises a pad in salutation. His round-mouthed smile widens.

Although they can’t be sure, Tomas and Tereza are flooded with relief. Aliens come in all shapes and sizes – but this one seems friendly.

‘We must have picked him up when we bumped the lever,’ says Tereza. ‘God knows how many galaxies we travelled through. He was probably just out for a walk. I feel sorry for him.’

As the echo of her words fades in the tomb, the most extraordinary thing happens – the Alien rotates. Very fast, in the wink of an eye, he twirls on the spot, smile fixed, eyes blinking. Thirty seconds later the same thing happens. And again. Every thirty seconds, a mini whirlwind.

Further enquiry into this circular rotating curiosity must wait: the more pressing matter is how to prevent this tomb from becoming their own. Tomas gestures to the Alien to remain where he is and takes Tereza by the hand to explore their prison.

Off the chamber beneath the impressive dome radiate chapels. Tomas reads the names – La Salle, Duroc – of two of the tomb’s inhabitants. Rounding a corner he sees another – Gratien – and then a monument representing sentinels guarding the body of their leader, Bugeaud. By the banners and martial symbols Tomas deduces that this isn’t an ordinary tomb. It’s for the military and houses the bones of the fallen brave.

Moving farther he discovers a Joseph and then a Jerome. Moments later he connects the names.

‘I can’t believe this,’ he says to Tereza. ‘Do you know who was served by Bugeaud and Duroc? The man Gratien and La Salle fought beside? Whose brothers were Joseph and Jerome?’

Tereza gives him a blank stare.

‘We can only be in one place,’ Tomas says. ‘Napoleon’s tomb.’

Hank 3: The marooned man’s flare …

What’s this fascination we have with fallen people? The convicted fraudster walks into a restaurant to be greeted by bowing waiters and a reverential silence. The drug-addict singer with foul manners is cheered in the street. The impeached president leaves office to applause and a waving crowd. Is it the thrill of proximity to something bad or the wish to taste it ourselves?

Hank’s fall from grace has a predictable consequence. He’s a hero. His confession turns him into a repository of wisdom on all things business and banking. Now he stands in the conference room of his bank, to answer questions from his admiring peers. He deals with the basics first.

‘How should you dress for success?’ asks an enthusiastic young banker, who is wearing a yellow tie and red braces.

‘Not like you,’ Hank replies, ‘people see you coming. You’re saying too much. White or blue shirt. Blue or grey trousers. Blue tie. Even a fancy watch gives you away.’

‘So once I look the part,’ says the banker, trying to cover his embarrassment with another question, ‘what attitude do I take? Tough? Direct? Listening? Subtle?’

‘Anyone with just one gear’s a loser,’ Hank replies, ‘especially the always-tough boss. That’s the ultimate cliché. Worse, it’s predictable. You’ve got to adjust to every situation. If the other side’s aggressive, shut up. It can disarm. Don’t get into a shouting match – it leads nowhere. If you know what you want, play the tough guy. If you’re not sure, dissemble. Sometimes crack a joke. Other times play dumb.’

‘Then it’s OK to lie?’ another banker asks.

Hank pauses. The reconstructed man needn’t hold back. He wallows in his candour.

‘Truth in business today isn’t absolute. It’s not a question of truth or lie. Right or wrong. Truth is elastic. It bends.’

‘Give us an example,’ asks the same questioner.

‘A deal has become expensive,’ Hank replies, ‘you need to pile on more debt to get it done. What do you do? Advise your client not to go ahead? Then what happens to your bonus? So you don’t lie. But you don’t exactly shout “Stop!” Remember, it’s your job to do deals. You tell me: how many have you done that didn’t work out for your clients?’

‘But that’s not illegal,’ says the questioner. ‘It’s not wrong.’

‘Like a grown man sitting all day in front of a bank of screens, all to the end of making money for himself. Better not to think about right or wrong.’

‘OK, once you’ve got your dress straight and learned the subtleties of truth,’ asks another questioner, ‘what’s the biggest weakness to look for in the other side?’

‘Bullshitting about money,’ Hank replies almost before he’s finished the question. ‘Like trying to fuck girls by showing off about your car or bonus. Only losers slip money messages into the conversation, whether it’s business or personal. They’re usually lying, anyway. It’s the biggest sign of weakness. Strong guys never mention money.’

‘And the biggest killer?’

‘Not taking risks. You can read every business cliché about setting goals, hiring the best, striving for excellence. But at the end of the day it’s all about taking risks, the bigger the better. Even if you fail. Everyone’s the same. You’ve got to be different. “Me too” people die. Risk takers survive.’

‘And how do you do that?’

‘Go mad,’ Hank says, shaking his head like a lunatic. ‘Think beyond your wildest dreams. Take your ideas to a crazy place. Then pan back to something more realistic. I guarantee you’ll have pushed your thinking further.’

‘And how does that apply to us bankers?’ asks the chief banker, who sold Boss Olgarv the slaughterhouse business.

‘It doesn’t,’ Hank replies. ‘We think we take risks but we don’t. Or rather can’t. It’s not our money. What’s the worst thing that can happen to a banker? He gets fired for making a mistake. And to a risk taker? He goes bust or loses his house. We’re not in the arena covered in filth, sweat and blood. We’re the pond dwellers. The ones who feed off other people’s bits. We’re there to organise the show, then sit back and watch.’

‘Come on, Hank,’ says the chief banker. ‘We’re better than that. We also give back. What about the charity events we hold? And the good causes we work with?’

‘Boom or bust bankers worldwide earn vast sums,’ Hank replies. ‘We give only the tiniest amount and its not systematic.’

‘So what are you suggesting,’ asks another questioner, ‘that bankers should tithe?’

‘That’s exactly what I’m saying,’ Hank replies. ‘Imagine what that money together with our work ethic could achieve. Just think if each bank adopted a charity, school or hospital, and it became part of our daily business to support that institution; to use our skills to make it a centre of excellence. Once we succeeded with one we’d move on to another. Think of the public reaction. We’d go from being pariahs to philanthropists overnight.’

‘That’s idealistic,’ the chief banker replies; ‘there are always issues, local politics, complexities.’

‘Nothing compared to the deals we do,’ Hank replies. ‘Within a decade, we could become the most powerful lobby in the world. Our enterprise skills could focus on difficult areas, eradicate problems. We’re capable of making a difference in whole sectors, on a national scale. Why should we do it just as bankers, to grab money for ourselves? Why not do it as philanthropists and influencers? We have the talent but not the will.’

‘Our job’s finance, not management,’ another banker says.

‘Why not?’ says Hank. ‘Finance; ideas; organisation: it’s all the same. Take a small-sized African country whose GDP is less than the average bank’s profits. It’s corrupt, inefficient and has a myriad of social and political troubles. But there is potential in its resources, geographic position and people. The bank, which has thousands of bankers, assigns just a few hundred to work full time for this country. The problems are enormous, the corruption intractable, but the bank uses its power, influence and knowhow to make a difference. It might take years, but in the end there would be a result.’

Hank pauses, reflecting on the apparent impossibility of his message.

‘In history,’ he continues, ‘bankers ran whole countries or communities: the Medici in Florence; the financiers in Venice. Their motivation was just as much civic as it was commercial; they built fabulous cities and endowed schools, hospitals and charities that still endure today. We live in a fast, ruthless, money-mad world. We need to return to these values; to a mindset where the banking class systematically thinks and acts like the financiers of old. So our epitaph will be: they were great bankers, made money and lived happy lives, but also did incredible things for others.’

‘It’ll never happen, Hank,’ says the chief banker. ‘The days of bankers behaving like that are over. Anyway, you sound moralising and quaint.’

‘Maybe you’re right,’ Hank replies. ‘But sometimes the best that you can do in life is send up a flare, like the man marooned. However remote the island, someone might just see its light in the sky.’

The greatest Frenchman of all time…

The Emperor Napoleon lies in the tomb of Les Invalides in the middle of Paris, surrounded by his generals and brothers. His body is interred in an elaborate encasement of six coffins built from different materials, including mahogany, ebony and oak, one inside the other. The outer coffin, of red porphyry, sits on a green granite pedestal surrounded by twelve statues of victory under a window-lit dome.

Tomas and Tereza walk around the magnificent sarcophagus and Tomas touches its lip in awe.

‘The night before my execution,’ he says, ‘I found a perspective on life at last. It was my dying wish to discuss it with a great man in history.’ He pauses before continuing. ‘You said your machine could raise the dead.’