Part II

Chapter VIII: The Dead Man

My friend lapsed into a dark silence, his cold pipe clenched in his teeth. I still had questions, but when he was like this, his mind was somewhere else entirely, constructing and tearing down delicate edifices over and over until he found one that could stand independently, even when shaken from all sides.

My own thoughts examined what he had revealed, and I tried to imagine an entire world at war. Smaller battles and wars are fought every day in every corner of the planet, but I couldn’t conceive of something on the scale that Holmes implied. Granted, the Crusades, spanning hundreds of years, had been along the same lines, but they were confined to smaller and focused geographical areas and separated by great distances, and travel to those places had taken inordinate amounts of time. The Mongol invasions of previous centuries, reaching to central Europe before withering, had been more like what Holmes feared, but those long-ago battles had been about conquest for territory, and not whipped to a frenzy by men of great influence with modern motives.

No, what Holmes described was war on a global scale, taken to a level of deadly destruction that would have been unimaginable just a generation of so earlier. Gone were the days when England and Europe had been protected by distance. This would not be like the various local conflicts, earth-spanning as they had been, of the Seven Years War more than a hundred years in the past. The ability to inflict death had achieved entirely new levels. The American Civil War of a quarter-century before had shown the world that warfare was now a completely different type of animal indeed. Modern transportation and communications could move armies in a fraction of a fraction of the time that it had taken just a century before. And if some brilliant general or tactician happened to wrest for himself a position of leadership within the councils of our enemies, by way of a mistaken belief in a supposedly magical rock, then we could indeed be facing a very grim prospect.

Like all knowledgeable Englishmen, I was aware of the scope and breadth of our Empire, and also the resentment – some of it earned – that it caused around the world. Holmes was correct: If the idol were to fall into the wrong hands, it would be as if a lit match had dropped onto an already wide and thin sheet of spilled lamp oil. The resulting conflagration could flash and spread with incredible destruction.

We remained quiet throughout the rest of our journey, each deep within our own imaginings. I was sure that Holmes was playing out variation after variation, while I was sunk into my own memories of the horrors of war.

Upon reaching the quaint station in Chelmsford, we quietly changed trains, only waiting for a few minutes before heading northeast, toward Sudbury. I had no idea where our final destination was to be, but I was following Holmes’s lead, as I had done so many times before.

As we took our seats, my coat knocked against the woodwork. Holmes glanced toward it and then smiled, knowing that the noise had come from my ever-present service revolver.

Somewhat before reaching Halstead, my companion, still quietly thinking and smoking, shifted, readying himself to stand. I followed suit, and in a few moments, we had disembarked upon a small platform of something between a real station and a mere halt. Locating an official, we were told that there was only one cab for hire, but that it was currently in use, taken by a passenger from the previous train. “They had to go about five miles out. If Thomas – that’s the cabman – is sent back instead of being required to wait, then he should be here soon.”

“Tell me,” said Holmes, with a gleam in his eye, “was the man on the previous train a balding fellow, tired looking in an ill-fitting suit, no coat, and rather nervous?”

“Ayuh, that would be him,” said the official, raising an eyebrow, as if inviting an explanation or further comment. However, he received neither, and Holmes thanked him curtly, turning toward me.

“Williams,” he confirmed. “After he left the telegraph office, he must have made his way directly to Liverpool Street Station and set out for here on the earlier train, no doubt following some instructions that he had been given if this situation ever arose. In the meantime, we made the effort to detour by Ian’s town house.”

Remembering another question, Holmes turned back to the official, who had never really stepped away. “This other man,” he said. “Did he go to the great hall, the Earl of Wardlaw’s residence, about halfway between here and Steeple Bumpstead?”

“Ayuh, that’s right. But it’s more like halfway between Toppesfield and Gainsford End.” He seemed as if he were willing to stand and debate it with us.

Holmes nodded and handed over a coin, for which he received a routine and mumbled thank you. Then, the man took a better look at what he had received, and said, “Much obliged indeed.”

The official left us then and went into an office. Holmes began to pace the platform while I stepped into the station’s waiting room, taking a seat on a worn but solid bench by one of the walls near a stove, struggling and ultimately failing to warm me.

It must have been only ten or fifteen minutes before a ragged carriage became visible in the distance, heading our way. I walked out and joined Holmes at the edge of the platform while the single driver drew near. Finally, he stopped within hailing distance and asked, “Are you gentlemen waiting to hire the station fly?”

When we said yes, he glanced longingly toward a low building that seemed to be a pub a few hundred feet away. With a sigh, he stated that he needed to water his horse, and then he would be at our service.

When we were underway, the driver shook his head. “I go for months without driving out in this direction, and then do it a couple of times in the same afternoon.”

“The man you took before,” said Holmes. “Did he say anything?”

“Not a word after telling me the destination. He did seem anxious, though. He was tense, and sometimes he had to wrap his arms around himself to keep his hands from picking at one another, as he did when he just left them in his lap. Or maybe he was just cold.”

The five miles passed without incident, although I would have imagined that the distance was actually somewhat greater as we wound this way and that on the twisting narrow roads. Finally, after a sharp left bend, we topped a small hill and could see our destination immediately before us. “Wardlaw Hall,” said the driver, gesturing with his whip. It was the only time he had used it on the entire trip.

I was surprised. I’ve learned over the course of my life that nothing ever turns out as one first imagines it. This is true for attending social events and meeting strangers, and especially visiting new locations. In spite of that, I had supposed that this house would be somewhat resplendent, given that Holmes had related how Ian Finch, the Earl of Wardlaw, had been quite fortunate in recent years. The town house in Wellington Square had been nice enough, if rather conservative. I had thought that this would be a showplace. Instead, what was revealed as we came over the hill was a massive structure that had been left untended and unloved for so long that it was in danger of becoming a derelict.

The landscape was completely out of control. There were great hedges, some probably hundreds of years old, now so completely ragged that it was unlikely they could be reshaped without killing them. The lawn near the house, which had probably once been green and well-manicured, was now weed-choked, and numerous low spots had sunken and formed, holding ponded rainwater that was now sheeted with ice, pierced by thick stalks of invasive plants like spears through a glass. Of course, it was January, and one would not expect the landscape to have the vibrant life of spring or summer, but this went beyond something that was merely lying fallow due to winter. This had been left to return to the wild, as if the owner had no further interest in cultivating it.

The dead gray grounds were the same color as the pale washed-out stone of the house. Taken together, they appeared to be some massive watercolor, with the lines between sky and building and earth blurred, as though a bucket of mop water had been tossed on the finished painting, softening the drab colors and letting them all run together.

“This cannot be the house of a successful man,” I whispered to Holmes.

“I’ve kept track of Ian over the years, and I know that he has done well for himself. Seeing this, I’m not sure in what way he chooses to express his success, but certainly he doesn’t measure it by showing off his estate.” A little louder, Holmes spoke to the driver, asking, “How long has the house been in this condition?”

“I can’t rightly say. I rarely get out this way. I do know that it was in this shape the last time I was here.”

“When was that?” asked Holmes.

“Oh, six months or so ago. It’s hard to believe they could let it get to this state. I’m not surprised, though. The Earl let his staff go quite a while back. My cousin used to work here, back when the Earl’s father was alive, and it was certainly different then. She, like all the others, were surprised when the new Earl turned them out. He only kept the butler.”

“Fisk, I believe was his name?”

“No, he died. This one came later. His name is Dawson.”

“Do you know if the Earl is at home now?”

“No idea. They have their own horse and buggy, and so of course I’m never hired by them. When the Earl comes down from London, he wires ahead and Dawson comes out for him.” He flicked the reins, with no apparent acknowledgement from the horse, and added, “I’m the one that brings out the telegrams when one arrives – though those are rare enough.”

“But you delivered one earlier today?”

“I did,” the man said, suspiciously now. “Two, actually.”

“Two?” I asked. I turned to Holmes. “The one sent by Williams, certainly, but who could have sent the second?”

The driver just looked at us, probably wondering why it was any of our business. Holmes asked, “Did you make separate trips for each of the telegrams that you delivered?”

“No, I brought them out together at the same time.”

“But one arrived before the other?”

“Somewhat, I suppose, but there wasn’t a great deal of time between them.” He looked as if he wanted to ask why we were concerned. “We don’t worry ourselves so very much about these things out here, I suppose. I had intended to deliver the first telegram at some point, and then the second one arrived, so I decided I’d better get to it. I thought two telegrams might mean a tragedy, so I brought them and put them into the butler’s hand, and then went back to the station.”

“And then you brought out the man who came down on the train?” I queried.

“No, he was with me when I delivered the telegrams.”

“That’s right. You did say you made ‘a couple of trips’ – this one, and the one with that man – Williams.”

“Three birds with one stone.” The man laughed.

By then we had dropped down the low slope and were approaching the front door. From this closer vantage, I could see that long strips of paint were peeling away from the wood. Holmes roused himself. “The man you brought out before us,” he asked. “Did he ask you to wait?”

“No, although I would have. He was surprised when I jumped down when we got here, and then irritated when he learned that I was just then delivering the telegrams. But then he calmed himself, and just handed me some coins – more than what he owed. The door had opened before we reached it, as if someone had been watching for us. It was the butler. After handing him the telegrams, and seeing as how I hadn’t been instructed any differently by the man from the train – this Williams, I suppose – I turned around and left.”

We stopped, but apparently no one was watching for us this time, as the door remained firmly closed. Handing the fare to the driver, Holmes said, “I trust that this will be enough to retain your services for the journey back.”

He glanced at his palm and smiled. “Certainly will.”

“Excellent.”

We climbed down and approached the door. I could see that the peeling paint was matched by the fine sun-damaged cracks that were appearing in the wood. There were streaks of greenish stains along the stonework arching over us. Simply judging from the front door, one could see that if the house weren’t rescued and repaired soon, it would reach the point of no return.

However, the bell still worked, for we could hear it from somewhere deep inside. Holmes was in the act of ringing it a second time when the door was suddenly pulled open rather violently by a most curious little man.

He was probably an inch or two under five feet tall, wearing a formal black coat that looked like something styled from fifty years before. Resembling the walls of the entry arch in which we stood, it seemed to have been damaged by the damp and streaked with a greenish sheen. He had on a rusty white shirt, and a filthy white waistcoat was buttoned across his round barrel chest. It was stained with something that looked quite like dried mustard.

His odd trunk was supported by short pipe-stem legs, encased in dull black pants. He had very large hands for such thin arms, and they were swollen with arthritis, the knuckles red and knobby. The thumbs were longer than normal, curving out away from his hands, and they had unusually wide but short nails. The most curious feature of all, however, was his head. It was jammed into his body, so that it seemed as if it was an extension of his ribcage, thus forcing him by its fixation to always look straight ahead, turning neither left nor right, or even up or down, without some great degree of pivoting difficulty. The skin of his face was red, and he was clean-shaven, except for a patch or two along his upper cheeks or jawline where he had missed a few stray white whiskers. His hair was thick, although his forehead was high, and it was white and unbrushed, sticking straight up in an uneven tangle that most resembled the wild hedges surrounding the house. Finally, his features were frozen in a scowling grin, or perhaps it might better be described as a grinning scowl, his lips pulled back in a rictus over his unusually big and strong-looking yellow teeth. He looked for all the world like a cross between the Wee Falorie Man, Humpty Dumpty, and some ghastly illustration out of a Dickens novel – although I would be hard-pressed to decide exactly which one had ascendance over the other.

His voice sounded exactly as I would have expected: Rough, uneducated, and somewhat garbled, as if his mouth had difficulties forming the words.

“Can I help you?” he asked in some semblance of serviced politeness.

“We are here to see the Earl on urgent business,” said my friend. “My name is Sherlock Holmes, and this is my associate, Dr. John Watson.”

The man may have looked like a caricature, but one could see that he was intelligent, if only in some low crafty way. A flash of recognition at my friend’s name caused him to close his eyelids for a just a fraction. Then, his manner seemed to change, and a note of whinging despair came into his voice.

“Are you with the man who came here before?” he said, a noticeable cringe in his tone.

“We have been trying to catch up with him,” replied Holmes.

The man nodded. “Sirs, I am so glad that you’re here, I am! There has been an accident!” His voice lowered dramatically with that declaration, and he looked at me, as best he could, turning and tilting his entire body. “You are a doctor, I believe?”

“I am.”

“Come quickly, then. Perhaps you are not too late.”

He moved aside, letting us into the house. The strong smell of cool damp and decay assaulted my nose, and I gave an involuntary cough. Clearly the roof was leaking somewhere, perhaps in many spots, to have so let the house get in this condition and to feel this fetid inside.

The door closed solidly behind us, and my eyes struggled to adapt from the weak sunshine we had just left. There was only a single low-burning candle on a side table, and the little man picked it up too quickly, causing the flame to momentarily flicker. “This way,” he said, shuffling through a large doorway that led us deeper into the house. “Hurry.”

“On your guard, Watson,” whispered Holmes as we followed.

We twisted through dark halls and darker passages, moving ever toward the rear of the sprawling building. Finally, the little man threw open a door, causing me to stop in my tracks. I was blinded as my eyes were filled with brightness. We had reached a grand ballroom, lined all along one wall with south-facing windows reaching to the high ceiling. The floor was of white marble, as were various columns around the room. The windows faced into the afternoon sun, now low in the January sky, its light flooding in and reflecting off the countless white surfaces.

The little man had kept walking toward a far wall, and Holmes, who had also stopped beside me, resumed in the same direction. Moving to keep up, I reached them both just as the butler pulled aside a heavy drape, revealing a shallow alcove. He shifted the candle to his left hand and reached out with his right, taking hold of what I could now see was the edge of a door, covered with the same rich plaster-like material as the walls. It would be concealed when closed, and it seemed to be very heavy. It was all that he could do to force it into motion.

“In here,” he said, panting. “There has been an accident!”

I could see that the door was very thick, and appeared to be made of metal underneath the outer covering. Could this be the vault mentioned by Holmes, where the idol had been kept before being moved to the Museum? Was this where it had been kept again following the substitution?

We stepped inside and, by the sole light of the candle, I could see a body crumpled on the floor. It smelled of death in the close little room. The chamber was barely six feet in height, about five feet from side to side, and eight feet deep. Like the door, the floors, walls, and ceiling also appeared to be made of metal. There was no light, save for the thin candle in the butler’s grip.

I pushed my way forward, intent on examining the body. Holmes maneuvered himself behind the butler, allowing the light from the feeble candle to project without being shadowed by his tall thin frame.

“I found him this way,” said the little man. “Can you help him?”

I carefully examined the body. The dead man was crumpled, face down upon the floor. His skin was already cool, and I knew that he was beyond my help.

“He’s dead, Holmes,” I said. “It’s Williams.”

“Can you tell how he died?”

“There is no great amount of bleeding. While there may be other trauma that I cannot find without a better examination, there is a wound at the top of his neck, a narrow laceration. He appears to have been killed by the direct insertion of a thin blade into the base of the skull, either severing the spinal cord, or more likely entering the cerebellum of the brain, depending on the angle. An autopsy can tell for certain.”

Holmes took the candle. “You are Dawson, the butler?”

“I am. How did you – ?”

“Where is your master, the Earl?”

“I… I will go and fetch him.” He turned and scampered out of the vault.

I expected Holmes to join me in examining the body. Instead, he put his finger to his lips, and then said, loudly, “If you will just help me turn him over, Watson, I think we can find one or two other interesting facts.”

But he didn’t move to the body, where I still crouched. Rather, he gestured for me to join him, nearer to the vault door. I rose, stepping with exaggerated care so that my footsteps remained silent. We had just stopped when a shadow, clearly that of Dawson, appeared on the outer floor, alongside that of the great metal door. And as we watched, the door began to slowly swing shut!

“Quickly, Watson!” Holmes cried, and we both rushed forward, pushing back against the door and reversing its motion. I heard Dawson grunt, and then with a frustrated sob, he gave up. The door moved freely, and we heard the sound of a falling body as we stepped out into the alcove.

Dawson was already picking himself up from the floor, rolling awkwardly to one side with his stiff frame, when I placed myself in front of him, having trained my gun on him in the process.

“Watch him, Watson,” said Holmes, returning to the vault, this time to truly examine the body without fear of being trapped. “He is as dangerous as a swamp adder.” But Dawson simply lay there, half propped, looking off into space and muttering angrily to himself.

“You are correct – I can see no other wounds,” called Holmes before stepping back into the great room. “Of more interest is this vault. No ventilation, no lights, nothing on the inside of the door that can open it. If this creature had succeeded in shutting us inside, we would have remained in there with a candle and the dead man until we, too, were corpses.” Looking down at Dawson, he snapped, “Where is the Earl?”

“Gone!” snarled the little man, his attention pulled back from his grumblings, and clearly no longer trying to appear meek or bewildered. “He received the warning.”

“Warning? From Williams?”

“Yes. That the truth is known. The idol is no longer safe.”

“Where did he go?”

Dawson only grimaced, and did not offer an answer to the question.

Holmes tried again. “If Williams sent the Earl a telegram, then why did he also need to come here?”

“Part of the plan. Always part of the plan. The Earl did not know but that he would need assistance if this should ever happen. Young Williams had worked for him for years, ever since they met when the statue was first taken to the Museum. My master paid him to keep an eye on things after the real idol was brought back home.”

“But why kill Williams after he arrived? What did that accomplish?

“The plan!” answered Dawson, looking at the floor, seeing something that we could not. “It all becomes part of the plan. The Master realized that Williams could offer nothing else, so he sacrificed him to tie off a loose end. And he saw it as a way to stop you as well. He knew that you would be coming. He showed me how to trick you into the vault.” Then his anger seemed to disappear as his face collapsed into sadness. A tear pooled on one of his rheumy eyes and trickled down his cheek. “I failed. I failed him. I wasn’t strong enough to slam the door. I have failed.”

Holmes turned away in disgust from the figure on the floor. “Give me a moment to look around, Watson. I suppose that Ian is truly gone now, but I’ll just make sure.”

For the next few minutes, I heard him moving through the house, and even outside. Then he returned, explaining that the house was truly empty. “I checked the stables. There is evidence of one horse, which has very recently been hitched to a dog-cart and driven away. I asked our driver outside, who would surely have been sent on his way by our friend here after we were sealed away, if there are any other roads back to the station. Unfortunately, there are a variety of different routes, which explains why we didn’t pass Ian as we traveled.”

“But how did he know for sure that we were coming, Holmes? Just because Williams told him that you had spotted the fake is no reason to assume that we would immediately beat a path here. You said that Williams didn’t spot you when you followed him from the Museum, and there was no one at the Wellington Square house to notify him.”

“Don’t forget the second telegram, Watson. I suspect that someone actually was in Ian’s house in London, perhaps another trusted servant like Dawson here. When we stood near the front door, discussing our plans to travel down here immediately, that person likely overheard us, standing on the other side of the door, and then sent the other wire. Although he only received the telegrams at the same time that Williams arrived, Ian knew for certain to expect us, and soon – although he had time to plan this macabre little trap, baited with Williams’s carcass.”

He stepped over and pulled Dawson to his feet by the grimy collar of the butler’s coat, marching him through the house with us to the front door. Outside, the driver was surprised, but when we explained the situation, he understood, and hurriedly drove away to bring the police.

Dawson didn’t speak again during the period that we waited with him in the house. Holmes used the time to further explore the vast premises, but he failed to discover any other clues, except for signs in the Earl’s disheveled bedroom of a hurried departure.

When the local constable arrived, brought back by our driver, Holmes identified the both of us, and luckily the policeman had heard of him. Soon other men arrived, clearly locals deputized to follow by the overwhelmed constable. After an hour or so of assisting their fruitless and frankly meandering investigation, we were transported back to the small village where we had initially entrained. Dawson was taken and placed in the sole small cell maintained in the village while we stepped over to the tiny post office to inquire about the telegrams that had been received that day for the Earl. Upon learning of our connection with the investigation, the fat man behind the counter rubbed his hands obsequiously and acknowledged that two wires had indeed arrived that afternoon. He showed copies of them to us, revealing that – as Holmes had predicted – the first was the one from Williams, and the other was from someone named Harbottle, sent from a Chelsea telegraph office, indicating in terse terms that two men referring to each other as Holmes and Watson had been at the Wellington Square house, and were overheard to say that they were proceeding on to the Earl’s home in Essex.

“No doubt we’ll find that Harbottle is the caretaker at No. 30,” said my friend. Turning to the fat man and holding up the copies of the messages, Holmes stated, “I understand that these were not delivered immediately.”

“Well,” the man drawled, “that’s right. It’s five miles out and the same back, and I just have Alfred, the boy, here for help around the office.” He gestured a thumb at a slack-jawed fellow in his mid-twenties, standing in the shadows behind him. “He delivers the messages to nearby spots here in the village, but we have an arrangement with the station cab for those that are too far for Alf here. When the second wire came in, I sent Alf to give it to Thomas Keller, the cabbie. Turns out, he hadn’t taken the first one yet, so he hopped to it, and went away with both of them.” He lowered his voice with added gravity. “It’s very rare for the Earl to receive wires these days. It’s been a long time indeed, and I felt that two so close together must mean something important.”

Holmes thanked him flatly for his time without giving any of the additional information that the man so clearly desired. My friend then dispatched a couple of wires of his own, the first to that location where he often sent messages to young Wiggins, one of the many members of that family who had served over the years as leaders of his unofficial Irregulars, asking him to arrange for someone to keep watch on the Earl’s house in Wellington Square, in the unlikely event that the Earl should return and go to ground there. The other was to Inspectors Gregson and Lestrade, our long-time associates from Scotland Yard, advising them to put out the word to be on the lookout for Ian Finch upon his likely arrival in London.

While Holmes was writing, the local constable came in, also intending to send a wire of his own, requesting assistance investigating the murder of Williams, whose body had now been brought back from the vault at Wardlaw Hall. He told us that he wanted to make sure that he adequately took care of any unexpected complications, since he admitted with open frankness that he had never been involved in something like this before. Both he and Holmes watched the fat man pointedly until they were certain that their messages were sent immediately, instead of being simply put at the bottom of a pile of things to be accomplished sometime that day.

Outside, Holmes had a few quiet words with the constable, who showed a sudden surprised expression. As he stepped away, he additionally advised the young man to keep Dawson in custody until further notice, charging him with our attempted murder if need be, as the odd dwarf’s true part in the events had yet to be entirely explained.

Finally, after shaking hands with the officer, we returned to the small station, where we confirmed that Ian Finch had indeed arrived on a dog-cart and caught the up-train that departed not long after we had set out for the Hall. Holmes shook his head in disgust. “A comedy of errors and lost opportunities, Watson. Surely the gods arrange these little near-misses to break up their eternal monotony.”

Finally, the next train arrived and we climbed aboard, to travel back to Chelmsford, and thence ultimately to London and Baker Street.

Chapter IX: Legal Matters

It was getting dark when we opened the door to the sitting room. I was immediately struck by a most unusual and unpleasant aroma.

Holmes noticed it too, as I could hear him decisively sniffing. I concluded that he must have forgotten some chemical experiment that had taken a turn for the worst. It would certainly not be the first time.

Mrs. Hudson had left our mail on the table, as usual, and I was surprised to see a box, about a foot square in both height and width, wrapped in plain brown paper. It was simply addressed to Dr. Watson, 221 Baker Street, London.

I picked it up and found that it was heavier than it looked. Returning it to the tabletop, I reached for a knife to cut the twine that bound it.

“Watson,” said Holmes in a low voice. “As you value both our lives, do not open that.”

“Hmm?” I said, glancing toward him.

“Step away, please. I have a suspicion…” He moved toward the door from where he had been standing in the center of the room. Opening it, he called for Mrs. Hudson, who appeared a moment or two later, having climbed the flight of steps with her usual stately manner, drying her hands with a towel.

“This package,” he said. “I see that it has no postage stamps.”

I looked and noticed that he was correct. How he had observed that from halfway across the room was amazing, and yet it was the sort of thing that he did every day.

“Did it arrive with the regular post?” Holmes continued.

“Why, no,” Mrs. Hudson answered. “There was a ring at the bell, and then I found it propped against the door. It couldn’t have been there for more than a minute or so, the time it took me to get to the door from the kitchen, but I saw no signs of whoever might have left it.”

“I’m sure that you weren’t meant to,” said Holmes, dismissing her with thanks.

He crossed to me and leaned down, peering at the package more closely, and sniffing again. “The smell is coming from here,” he said. As I bent to confirm it, he added, “It is ammonia, of course.”

“Ammonia!” I thought, trying to recall where I had heard that mentioned in the last day or so. And then, I knew.

“Baron Meade,” I sighed

“Correct,” Holmes replied. “He seems to favor explosives using nitrogen-based compounds. They are easily constructed from commonly acquired materials. And apparently he continues to blame you for his defeat the other night.”

“But… I was simply one of many.”

“Yes, but you have put a face to his anger.”

Holmes had the page boy call a constable, who in turn summoned Inspector Gregson. Our old friend had been spending a great deal of his time in recent months seconded to the Special Branch, as there had been renewed concerns since the previous November that a group known as “The Dynamite Gang” might have extended their activities to London, following statements that were made in the press by a radical Irish-American named Cohen. Investigation with Holmes’s quiet assistance had led to the arrest of two possible conspirators, Harkins and Cullan, but tensions were still running high. The discovery of Baron Meade’s home-grown plot two days earlier would only compound the situation.

Gregson soon arrived, bringing with him several of his men, all experts in explosives. They agreed with Holmes that the package was likely a bomb, and that fact was confirmed later in the evening when they detonated it at the special facility constructed for that purpose near the Shadwell Basin.

“It was the same sort of thing that was found in that house the other night,” Gregson told us a few hours later, over brandies by our fireside, “although on a much smaller scale. There was a detonator affixed to the string tied around the carton.” He fished in into his coat and pulled out the string itself, along with the folded wrapping paper. “The string went through a small hole in the box, and was attached within to the device. I knew you’d want to see these. We preserved the knot, but I think you’ll agree that it’s nothing special. No sailor tied it. Just someone who only knew how to produce a regular knot. The string is common. The same with the wrapping paper – exactly what you can find in a thousand places in London. Regular ink and typical pen as well.”

While Holmes examined the items, Gregson smiled at me. “Mr. Holmes is slowly rubbing off on us, Doctor. I, for one, unlike some down at the Yard, am happy to take advantage of whatever modern methods he can teach us to give us an edge on these criminals.” And he took a sip of brandy, holding it in his mouth with obvious pleasure for a moment before swallowing.

Holmes confirmed Gregson’s findings, and the policeman departed soon after, warning me to be careful in the future, as I was apparently being stalked by a madman.

After the inspector left, Holmes and I sat quietly for a few minutes, before he said, “He’s right, you know. You’re going to have to be on your guard.”

“It won’t be the first time.”

“Nevertheless.”

I shifted in my chair, watching the fire. I felt strangely ambivalent. I found that I didn’t care whether I was a target or not. A part of my mind knew that it was related to the ever-present hopeless feeling that was always there beneath the surface since Constance’s death. And I also realized that some part of me welcomed the fact that I was being hunted, as it might give me a legitimate opportunity to confront someone – anyone – and vent my anger. If that someone turned out to be a lunatic, so much the better.

Finally, to soothe Holmes’s apparent worry, I said, “The man is a coward. He won’t try anything face-to-face. He has to plant hidden bombs and send packages. I’ll simply be more careful to examine my mail before opening it.”

With a shake of his head, Holmes stood and wished me good night.

***

In the morning, I looked out and saw that the sky was clear, but not quite as bright as yesterday. It didn’t feel as cold either. I came downstairs to learn that Holmes had already gone, having left a note explaining that he had some things to arrange regarding the search for the fugitive Earl of Wardlaw and the missing idol. He pointedly did not warn me to be careful, but I knew that it was implicit. We both realized that Baron Meade was fully cognizant that his package hadn’t detonated, and that I was still alive.

When Mrs. Hudson came up later to clear the dishes, I warned her again regarding our latest enemy. Threats were nothing new for her, I’m afraid, but this latest variation, consisting of the delivery of an explosive device strong enough to raze the house, was. As always, she displayed her strong Scottish sensibility and refused to be terrorized or intimidated. Seeing her example, how could I offer anything less?

I set out in plenty of time to meet Dr. Withers, in order to sign the papers that would exchange my medical practice, and all the hopes that had been appended to it, for a sizeable payment. I would have traded it all and lived in penury for the chance to redeem Constance from her fate, but that was a foolish and unfulfillable wish. Since her death, I couldn’t stop imagining what might have been, which only led to a greater sense of suppressed anger. I didn’t know how to extricate myself from this cycle, and I felt that it was growing stronger. Holmes had tried to distract me with tales of old cases and adventures, and Mrs. Hudson had overwhelmed me with kindness and favorite foods. But still the feeling persisted.

It was with this on my mind, and my teeth gritted, that I stepped outside, looking from left to right, hoping to see Baron Meade lurking somewhere, so that I might discuss the little episode of yesterday’s “gift”. My fists curled involuntarily, but uselessly – as he was not there.

I hailed a hansom and set out for the offices of my solicitor, Mr. Marchmont, in Gray’s Inn. I looked forward to settling the business quickly, and then perhaps walking to the nearby Ships Tavern and having a pint of the Old Peculier, or maybe two, as a solitary toast to my broken plans.

But that plan, too, was destined to fail.

A taciturn secretary ushered me into the large room where Marchmont met with clients. The lawyer, a heavy-set middle-aged fellow, stepped forward, his chubby face wreathed in a smile, to wring my hand in both of his, while past him, I could see Dr. Withers rising in greeting.

Beside him, no surprise I suppose, was seated his daughter, Jenny.

There was no reason why she shouldn’t have been there, but again, there was no reason why she should have, either. I ought not to have been surprised. Her plans and future were as bound as those of her father to my old practice. It was to be her home as well, and I had the impression that she would be of some daily assistance in her father’s work, to one degree or another. Yet, I found myself somewhat irritated by her presence, and I didn’t know why.

Dr. Withers offered a hearty greeting, and Miss Withers nodded with a quieter but no less sincere, “Doctor.”

Marchmont settled me on one side of the table, across from the doctor and his daughter. The lawyer and a member of his staff placed themselves at one end, and with the two interested parties on each side, began to explain the several documents that were involved. His assistant kept them in order, passing and retrieving them as necessary to be signed by one or the other of us, or both. I found myself recalling a similar scene, just a bit over a year before, when I had attended the same sort of ceremony, but that time as the eager purchaser. Constance and I were not yet married then. In fact, she was still traveling from the United States with her mother. After the procedure was concluded, I had immediately taken myself off to Kensington and my new home, and had let myself into the empty building to wander about, somewhat in shock at my good fortune. The world had stretched before me, full of promise.

Now, all that I could see before me for certain was that I planned to have a pint at a nearby pub, and that a madman was trying to kill me.

My reveries were far more interesting than what was occurring in the office, and at one point, my attention had to be called back to the present when I was asked to turn over my key to Dr. Withers. “Oh, of course,” I said, pulling it from my pocket. The lawyer laughed and rubbed his hands, and then progressed to other legal pronouncements, as I again lost interest.

Then Marchmont was congratulating us, and asking if I wanted his office to take care of depositing so large a check at my bank. “Cox and Company?” he confirmed. I nodded.

As we all stood to leave, Dr. Withers said, “We must celebrate. And I have something I’d like to discuss with you, Doctor. Will you join us for lunch?”

My first reaction was to apologize and excuse myself. But I saw that Miss Withers was looking intently, as if she was as sincere as her father sounded. I thought one last time of my plan to walk to the Ships, and then let it sail away.

“Excellent,” said Dr. Withers. And he led us outside to find a cab.

If Miss Withers hadn’t been with us, we could certainly have walked, in spite of the cold. We drove south for only a few blocks before angling into Aldwych, and thus into the Strand. There was only time for a bit of polite conversation about the weather before we arrived at our destination, Simpson’s.

I knew that women were not allowed to join us, but I felt that my long association with the place would earn a blind eye from the staff – as it did. Long a favorite of both Holmes and myself, I was a regular patron of this historic restaurant. It was often the chosen setting to celebrate the conclusion of a particularly difficult case, or simply the obvious destination if one wanted a good bit of roast beef. I should have felt some relief in that it had never been a favorite of my wife’s, as she hadn’t ever warmed to British cooking, and thus dining here would hold no memories of her. However, the fact that she had simply expressed an opinion about the place, even a negative one, was still enough of an association that thoughts of her flooded into my mind.

Understanding the doctor’s kind offer, I pushed aside my feelings and resolved to devote myself completely to being a gracious guest. Still, I couldn’t help but observe the prominent mourning band on my own sleeve as I raised my arm and reached out to assist Miss Withers as she stepped down from the cab.

Inside, we were led up to the first floor dining room that looked out over the busy street. It was comfortably lit, with the high north-facing windows illuminating the room without overwhelming it. I suspected that at certain times of the year, the afternoon sun would painfully reflect off the glass across the street. The same thing happened during summer mornings in Baker Street.

The food, as usual, was excellent, and the company quite companionable. We each opted for the famous roast beef, traditionally cut for us at the table from a distinctive rolling cart. The doctor and I had a Yorkshire Pudding with our beef and vegetables, but Miss Withers opted to avoid it. Conversation ranged from doings in Portsmouth versus London, individuals that we knew in common, and polite questions regarding my association with Holmes. Neither seemed to be either very aware or interested in his investigations, which was something of an unusual relief. There was also a pointed avoidance of my recent bereavement.

Dr. Withers related how he had come to injure his leg, explaining the limp that I had noticed the day before when he descended the stairway. “It was in early September of ’72, and my unit was in Honduras. Things had been tense for several years, ever since the Icaiche Mayas, who controlled the jungles in the lower peninsula, had occupied Corozal Town a couple of years earlier. I had only been at my post a little over two weeks when they attacked Orange Walk Town, resulting in a retaliatory raid.

“It should have gone like clock-work. We had incendiary devices that would fire through the air, allowing us to burn the natives out of their houses while staying well back from any return fire. They were thunderstruck, and quickly surrendered. They lost the taste for the fight and overthrew their leader, a surly chap named Canul, who had been in charge for several years by then.

“But there were still a few pockets of resistance, and I was attached with a group making a routine sweep when we encountered one of them. Some unexpected shots wounded one of our commanders, not fatally as it turned out, but as I was treating him, a bullet entered my leg from behind, subsequently exiting from the front with a chip of my knee-cap along with it.

“Miraculously, there was no more serious damage, and I healed rather quickly. Over the years, it hasn’t really given me any difficulties, except when descending stairs, or during cold weather, like we’ve had for the past few days.”

“Father was sent home to recuperate,” added Miss Withers, “and while he was here, mother passed away.”

Dr. Withers nodded. “She came down with a fever, and as I was flat on my back recuperating, I was unable to assist in her treatment.” He added, in a softer voice, “I couldn’t spend any time with her at all at the end.”

Miss Withers laid her hand upon her father’s. “She knew how you felt.”

Conversation faltered at this point, and nothing more was said until the waiter returned to ask if we needed anything else. The doctor requested pudding and coffee, and in spite of the fact that I felt quite full indeed, I joined him.

As we were finishing the last bites, talk turned to the practice itself, as Dr. Withers picked my brain regarding certain patients, and which of those he might expect to retain following the transfer of ownership. Of course, as part of the purchase process, he had been given access to various documents, including patient records, in order to determine the viability of the operation. He was excited to obtain the lease to the building because of its excellent location, but in acquiring the practice, he was also paying for something much more ephemeral, for there was no guarantee that the clients that I had worked to earn would stay with him.

Some patients would naturally leave for different physicians, while others would remain, either out of habit, or simply to give him a try. Certainly, he would take on new clients who had shown no earlier interest in seeking my advice, and eventually, if he worked hard and proved to be a good doctor, as he seemed to be, the practice would continue successfully, and would even grow. But he still wanted my opinion to help make the transition as smooth as possible.

“It is related to that,” he said, “that I wished to discuss something else with you.” He cleared his throat and continued. “I – that is to say, we – realize that your loss was very recent.”

His mention of something that had been approached indirectly but tacitly avoided so far throughout the conversation surprised me a bit. I saw that Miss Withers was watching me intently, and I nodded noncommittally, a reaction that could mean anything.

“We understand your desire to divest yourself of any painful connections to your former home and practice. I must admit that I felt the same way when my wife died. Newly widowed, I chose to leave the Army in order to raise Jenny. I couldn’t bear to stay in that house where we had all lived, as every aspect of it reminded me somehow of my wife. The furniture we had picked together – each piece suggested a memory or story to me. The wallpaper, unnoticed by others, reminded me of the decisions she had made to select it. Eventually, I did what you are doing, and sold out and moved to a new location.

“Now obviously, as the purchaser of your old practice, I cannot turn around and tell you that you’ve made a mistake. I understand what you’ve done, and why. But I can tell you that starting over somewhere else is going to be a lot of work, should that be your plan. From what I’ve seen, and from the records that I’ve examined, you are a good doctor. A man of good character as well. And even if you plan on stepping away from a practice altogether, I must urge you not to completely sever your ties from what you’ve accomplished.”

I believed I understood the direction he was taking. “Are you asking what I think you are? For me to maintain a connection with the practice?”

He nodded, looking relieved that it was now out in the open. “I am. I know that there is a natural tendency for a man in your situation to withdraw for a time. I felt it myself. But, knowing what I know now, I believe that it is the incorrect path. You should work through it, and keep moving forward, and avoid losing the professional momentum that you have attained. If you allow yourself to roll to a complete stop, every day afterward will be that much more difficult in terms of breaking yourself loose again, and inertia will own you.

“You know this practice,” he said, leaning forward intently, “and you know these patients. You will not have to learn anything new by remaining involved in their care, and quite frankly it would be of benefit to me as well, in order to ease the transition. I’m not asking that you continue to be associated on a full-time basis. Rather, you will act as a consultant, assisting part-time as you wish and as needed. You can still work in the hospitals, or as a locum for someone else, even fulfilling that function for me as well. You might even have time to assist Mr. Holmes on the occasional investigation, as you have done before.”

He leaned back before concluding, “Well, I hope you’ll consider the idea. Work is the best antidote to sorrow.”

My eyes widened slightly at that. It was what Holmes had told me regularly, beginning right after I had returned to Baker Street.

“I, too, hope you’ll be joining us, Dr. Watson,” added Miss Withers, touching my arm gently while putting a different emphasis on the word hope than her father had done.

I kept myself from looking down at her fingers, resting upon my sleeve. I nodded to move past the conversation, merely meaning that I would consider the offer, and not realizing then that what I was doing might be construed as a tentative agreement of sorts. But even as I was shaken by the idea, I knew that I had no intention of accepting it. In my mind, my life in Kensington was now a closed book. Today’s sale of the house and associated medical accoutrements and appurtenances had been absolute. If I had wanted to maintain a connection with the place, I wouldn’t have divested myself of it so quickly.

Clearing my throat, I thanked them for both the consideration, and for lunch. “Most appreciated,” I added.

We made motions of conclusion, and the waiter approached. Dr. Withers settled up, and we went down to the lobby. Retrieving our overcoats, we helped each other get prepared to return to the cold outside. As we started to walk toward the door, Miss Withers said, “One moment, Doctor,” and touched my arm again. She left her hand in place.

Her father noticed, smiled almost knowingly, and said, “I’ll secure our cab, my dear.”

As he passed on through the great revolving door, Miss Withers took a step to the side, placing herself in front of me. “We are quite serious, Dr. Watson,” she said. “About wishing for you to join us.” She moved her gloved hand upwards to brush the mourning band. “I understand how you feel, and know that it has only been a few weeks since your loss. But you are so much like my father, and watching him come to terms with my own mother’s death taught me that pushing past it is the only sure way.”

I started to speak, feeling that there were numerous unspoken implications hidden within her words. Before I could frame a response, however, she continued, “Growing up as I have has let me understand that clinging to the past can be like finding oneself trapped in quicksand. Refusing to move on, and also worrying too much about what society requires of us, can be such a terrible thing. Day-to-day conventionality is the same sort of trap.” She lowered her eyes, and then said, without looking up, “I’m sure you understand.”

I didn’t know what to say. I could not speak. I began to suspect what she was implying.

Misunderstanding my confusion, she gave a small knowing smile. “You are so like my father,” she repeated. “He told me that this would be your reaction, and he tried to prevent me from broaching the subject too soon. But I have always been strong-willed, as you will come to know, and I do get what I want. I know how to get it, and I’m not afraid to do the things that need to be done.” She placed her hand directly onto my mourning band and squeezed. “I know you think it’s too soon, and possibly it is too soon, but really, that mindset is just another conventional snare. I suspect that – ”

But while I thought that I knew, I was not to learn for sure what it was that she suspected, as the unmistakable sound of gunfire erupting in the street interrupted her further declarations.

Chapter X: Field Medicine

I rushed out of Simpson’s to discover Dr. Withers, lying in a crumpled heap near the street. Although it had only taken seconds to exit the building and reach him, there was already a pool of blood widening underneath his left shoulder.

I came to an abrupt stop as I saw who was standing just beyond him, a smoking gun hanging from his right hand. The screams of nearby women receded into a dull roar as my eyes met those of Baron Meade.

His gaze had lifted from the wounded doctor, and when he first saw me, he showed no signs of recognition. Then a look of amazed surprise spread across his face as he realized that I was standing before him, and not lying wounded on the pavement. I instinctively understood that he had been waiting for me to leave the restaurant, having known I was there. He must have been following me all morning, as he undoubtedly had the day before, when I had sensed that someone was watching me.

He would have known that his plot to bomb our rooms in Baker Street had failed. Surprisingly, he had decided to try something more direct. But waiting outside in the cold and anticipating his chance to take his vengeance for such a long period while we dawdled over our meal had made him careless. When Dr. Withers stepped out of the restaurant, the Baron had seen someone who had a strong resemblance to myself, and had jumped the gun, firing at the wrong man. Now, his confusion was obvious, as he found himself in the presence of what he must have believed to be two Watsons, one wounded or dead on the ground before him, but the other one – the correct one – alive, and willing, nay anxious, to fight. Even as I wondered to myself if there was a constable anywhere near, I launched myself toward the would-be killer.

He tried to raise the gun, but I swung my stick around as I ran, completing its arc on the Baron’s wrist. The strong wood, loaded with extra weight as a precaution learned long ago after aiding Holmes in his investigations, came to a satisfying stop as its momentum was arrested by the bones of Baron Meade’s arm, and the gun dropped from his lifeless hand. Before he could utter a cry, or prepare himself further, I slammed into him with my propelled weight, forcing him over backwards.

I grimaced as the impact jarred my teeth, and a shooting pain raced through my long-ago wounded shoulder. It never even occurred to me that my own gun was in my coat pocket, and I doubted that the mere threat of “Stop or I’ll shoot!” would have made any difference at all.

I felt my grip loosen on my stick, but rather than try to retrieve it, I let go and then curled my hand into a fist, swinging and catching the Baron on the jaw. There was a roar in my ears as I looked at this criminal, a man willing to indiscriminately take the lives of others as a recompense against his own loss, and at that moment I illogically associated him with the random unfairness that had taken my wife before her time. Just then, he represented everything that had caused me such terrible pain for the last few weeks, and I quite simply wanted to beat him with my fists until the rage that had been building inside me was gone and he was a pulp of shapeless meat, Hippocratic Oath be d----d.

With the prone figure laid out before me, I didn’t want to avenge Dr. Withers, or punish Baron Meade for his attempt to set off an explosion that might have killed hundreds. I simply didn’t know what else to do with my constant anger. It was always lurking just beneath the surface, and this man’s earlier plans to injure so many innocents, and this present attack on another undeserving victim when he stupidly believed he was attacking me, was enough to ignite the flame that I had tried to ignore.

Yet, as I braced myself to strike him once again, my foot slipped in the spreading puddle of blood, jamming backwards into the wounded doctor’s side. He didn’t make a sound as my foot kicked him, and a part of me was grateful that he was in his heavy coat, which might have just protected him from obtaining several broken ribs – provided that he was still alive.

I regained my footing and lurched forward, attempting to grab the Baron’s coat as he also stood. Part of me remembered just a few nights earlier, when I had held on so tightly to this very same coat as he had attempted to escape from the explosive-filled house following the disruption of his terrible plan. On this occasion, however, my fingers could not find a grip.

Baron Meade was torn between his desire to stand and fight me, and a cowardly urge to flee. He took a step back, and my tentative hold on his coat was lost. I reached blindly, and my fingers rasped against his face. I could feel that he had not shaved in days, likely since his earlier escape. He cursed and turned, but I managed to hook my fingers on the collar of his coat, yanking him backwards. I pulled him to me, and with my other hand, I began to piston a fist into the area of his kidneys. However, it wasn’t doing any good, as all of my blows were completely negated by the heavy fabric of the garment.

He pivoted on one foot, and my hand, still grasping his collar, was twisted painfully, while my entire arm was curled into a position around his neck, seeming as if we were entering an unholy embrace. I could see his face, very close now, and his teeth were clenched in rage. His breath was foul, and his eyes were bloodshot. He had several old bruises on his skin, no doubt caused by me the other night.

With a cry of rage, he pushed at me twice, and then raised his arms in a whipping motion, breaking free from my grip on his collar. “Don’t you understand?” he screamed. “They killed my son, and they have to pay! Why are you helping them against me?” He then lurched backwards for a step or two while I regained my balance, wincing at the fresh pain in my arm. Before I could recover, he turned and dashed down the Strand toward Trafalgar Square.

“Where is the constable?” I thought to myself. For a fleeting instant, it crossed my mind that the Baron possibly felt the same helpless anger and pain that I did, with the death of his son haunting him every day, but on a much greater and more destructive scale. I pushed the feeling aside, rationalizing that while I wanted to punish this one man who had just committed a murderous attack, Baron Meade wanted to kill hundreds who had never even heard of him, and who deserved none of his misplaced vengeance.

I remembered the gun in my pocket only then, but even as I reached for it, I knew that the fugitive would be beyond range before I could retrieve it. If I fired in frustration, I would likely hit a pedestrian, or send a stray bullet through one of the many windows looking down on the street. My only choice was to chase after him.

As I moved to pursue, and had only taken a few faltering steps, I heard a voice scream behind me, “Doctor!”

I stopped, watching the Baron dart this way and that through the mid-day crowds, like a deer cutting between bushes before reaching the safety of the trees. Turning to see who had called for me, and realizing vaguely that the voice sounded familiar, I saw Miss Withers, on her knees beside the wounded man, her own coat now soaking up her father’s blood.

“Father needs your help!” she cried urgently. I was frozen. Her words made perfect sense, but they didn’t seem to connect. I wanted to run down the Baron. Didn’t she understand that he was getting away? I realized my hands were clenched into fists, so tightly that pain was shooting up my arms.

“Doctor Watson!” she said again, this time with an edge to it. Commanding. “Do your duty as a physician!”

That reached me. I was a doctor. It was my obligation and covenant to treat the sick and injured. But I wanted nothing more in that moment than to injure rather than to heal. And yet, despite what I felt, my feet began to propel me in uneven steps toward the fallen man.

Dropping to my knees on the other side of the figure from where his daughter rested, I reached out carefully and determined that he still had a strong pulse. I couldn’t see the wound, and was considering the best way to turn him, when a voice interrupted.

“Here, now, what’s this?” Looking up, I saw the silhouette of a man wearing the distinctive helmet of a bobby, shadowed in the early afternoon sunlight behind him. I didn’t recognize him, but he apparently knew me. “Why, Dr. Watson!” he said. “What has happened?”

Rather than try to explain the nuances of the incident, I stated concisely, “This man was shot by a fugitive wanted by the Yard. Baron Meade. I attempted to stop him, but he just ran off toward Charing Cross Station. I’ll attend to the wounded man. You try to stop the fugitive.”

“How will I know him?”

“Middle aged. Dissipated. Dark thinning hair, heavy tweed coat. Looks as if he’s been in a fight, probably out of breath and acting suspicious. Be careful.” I noticed Baron Meade’s gun, which appeared to be a .22 caliber target pistol, still on the pavement. “He dropped that, but he may still be armed.”

“Right,” said the constable, leaving the gun and turning to lope off toward the west. Say what he would to criticize the official police, even Holmes was always willing to praise the bravery of the men who served on the Force. This time it was no different. As Constable Rawlins, for I now remembered who he was, turned without question to pursue a man willing to kill, carrying nothing more than his truncheon, his fists, and his number twelve boots, I could only admire him. I knew that it was nearly impossible that he would capture the Baron, or even overtake him, but it was still the best that could be done, an honest effort made by a good man.

As Rawlins’ boot-steps faded away, I could hear that he had pulled his whistle from his pocket, using it fiercely while he ran. Perhaps, if others became involved in the chase as well, there might be a chance that Baron Meade would be captured, although I remained doubtful.

Dr. Withers groaned and moved an arm, as if he were trying to gain leverage to turn himself over. Letting him know in a soft but clear voice that we were going to take care of him, I helped him to shift, so that he was lying on his back. Still not knowing how seriously he was wounded, I wanted to make sure that any movements didn’t make things worse. As the doctor sighed and settled back with his eyes closed, a man standing nearby stepped forward and placed a folded garment underneath the victim’s head. I saw without looking up that it was one of the distinctive coats used by the Simpson’s doormen.

Dr. Withers opened his eyes then, but he was clearly not yet entirely conscious. I pulled aside his coat as gently as possible, causing him to vent an involuntary cry. I tried to set aside my queasy recognition that he had been wounded in same general area that I had been at Maiwand. But this was different. The ragged projectile that had damaged my subclavian artery was fired from a Jezail rifle, and very unlike a .22 revolver bullet. It did not seem as if there was nearly much injury to the tissue here as what I had endured.

Dr. Withers’ shirt around his left shoulder was soaked in blood, and an initial examination showed that there was a bullet entry wound somewhere below where the trapezius muscle wound up and over his shoulder and the through the arch of the collar bone. Pulling back his coat further, I saw no blood pooling near the shoulder blade, or even staining the back of the shirt, indicating that the bullet was still inside him somewhere. Luckily, this meant that there was no ragged exit wound, with the terrible damage that would have been associated with it.

I feared that the bullet might have been deflected in some way, and thus traveled along a deeper path into his body, but feeling along the top of his shoulder through his shirt soon revealed an unnatural lump, which was almost certainly the bullet resting there, just beneath the skin. Most likely, the impact as the projectile went through the collar bone had been enough to slow its momentum, preventing it from exiting the body. The doctor was most fortunate. An exit wound have been much messier and larger than an entry wound, and even though this meant a painful recovery, especially while dealing with the shattered bone, he would not have to be probed in order to find the bullet in some other part of his body. The threat of infection still existed, but with proper care, he would most likely make a full recovery.

I pulled my handkerchief from my pocket and placed pressure on the wound. I was pleased to see that the bleeding already seemed to be stopping on its own. I realized that Miss Withers had been speaking. At first I had ignored it, thinking she was comforting her father. But then I understood that she was addressing me. “Dr. Watson,” she said, with some force to get my attention, “will he be all right?”

“Yes, I believe so.” I explained to her about the bullet’s path, and how the object would be easily recovered. “It could have been much worse.”

Her lips tightened, and she seemed to be trying not to speak. However, what she wanted to say would not be suppressed. “It certainly would have been much worse indeed, if you had persisted in running off after that man.”

“But… he had just shot your father,” I tried to explain defensively.

“You are a doctor,” she hissed. “Your duty is to the injured.”

“You don’t understand,” I explained. “The Baron intended for me to be the victim…” I trailed off, seeing a sudden confusion cross her face.

“What do you mean?”

“The man. His name is Baron Meade. Holmes and I stopped him the other night from a plot to blow up half of – well, a plot to use a bomb. He escaped, and now he apparently blames me for what happened. He left another bomb for me last night in Baker Street, and now – ”

A look of horror spread from her eyes outward. I thought that it related to what the Baron had done, but instead, she said, “My father was shot because this man thought that he was you? Because of something that you had done, relating to one of those investigations?” She said the last word as if it were filthy and unmentionable.

I nodded. “I’m afraid so.”

She started to speak again, but pursed her lips when Dr. Withers groaned then and reached up, grasping my forearm. “Dr. Watson,” he said. “What happened?”

“You have been shot through the left collar bone,” I said, speaking clearly and simply so that he would understand. It was the same as I had done so many times before on the battlefields, and how my own wounds had been explained to me when I had finally reached the Base Hospital at Peshawar. “The bullet is still inside you, lodged underneath the skin, high above your shoulder blade.” I eased the pressure on the wound and lifted the handkerchief. Other than minor seepage, the bleeding appeared to have been controlled. I knew, however, that we would need to be careful when shifting him to an ambulance so that the bullet’s entry wasn’t reopened.

Miss Withers stroked her father’s brow, but didn’t look up or speak to me. “Miss Withers,” I began, not sure of what I wanted to say, but unwilling to end the discussion. I felt the need to explain further, but at that moment, a constable pushed his way through the crowd that had formed around us, stopping beside me. I didn’t look up, but noticed the solid stance of his regulation boots as he stated, “Dr. Watson, I’ve summoned an ambulance. Rawlins sent me back to tell you that Baron Meade got away. He first cut down toward the Embankment, but then circled back and got into Charing Cross, where he made it onto a train. We’ve sent out word to be on the lookout for him, but he’ll have changed trains or gone somewhere else on foot before we can trap him, unless we’re just lucky.”

I thanked the man, and then helped to load Dr. Withers into the ambulance, which arrived at that moment. I ordered the driver to take us to Charing Cross Hospital, just down the street in the direction of Trafalgar Square. Miss Withers rode with us, but continued to whisper to her father, never deigning to look my way. I felt as if I should apologize, having inadvertently allowed my own difficulties to result in the mistaken attack on her father. But I didn’t know quite what to say, and she clearly didn’t want to hear it right now.

At the hospital, I succinctly explained the situation to the surgeon on duty, and helped to get Dr. Withers stabilized. The patient was conscious but somewhat confused, and after he was given morphine in preparation for the extraction of the bullet, he quickly fell asleep. I felt that there was nothing else that I could provide.

I walked out into the hallway, where Miss Withers was waiting, sitting alone on a cold chair, her coat pulled tightly around her, her father’s blood still staining it and the dress underneath. I related again the basic facts of her father’s condition, and what was now being done to remove the bullet. She nodded, stating with a cold expression, “I have assisted my father before, Doctor, in medical procedures. I’m aware of what is involved.”

Once more, I felt the need to add something that would elaborate upon all that she did not know or understand, and also to apologize for the way that she and her father had been pulled into my problems. “Miss Withers…” I began.

“Thank you for your help, Doctor Watson,” she interrupted, without looking up, her voice flat and cold. “As I’m sure you can understand, I would really prefer to be alone now, until I can see my father.”

“Is there anything that I can – ?” She shook her head, decisively.

Clearly she had nothing more to say to me, and I could only envision that any further attempt on my part to elucidate upon the facts of the matter would simply result in fumbling awkwardness. Choosing a different path, I told her that I would check back on her father tomorrow, and that if she needed anything from me to please let me know. Then, bowing my head, I departed.

Chapter XI: A Baker Street Conversation

I returned to Baker Street. Mrs. Hudson sensed my mood and offered to make some tea, but I wanted something stronger. Settling into my chair with a glass of whisky, I allowed myself to relive the events of the day. The visit to Marchmont’s offices, the lunch at Simpson’s – which was initially more pleasant than I would have expected. The following conversation in which Jenny Withers reemphasized her father’s offer, along with the implication of a second more subtle consideration for my future, and then the gunfire from the street and everything that followed.

I was unsettled, wishing to both venture forth and roam the streets looking for Baron Meade, and also to stay inside and while away the day until there was no time left to go anywhere. If I went out, I would have no idea where to search. The only way I might find the man, other than some infinitesimal chance encounter, would be to hope that he was already back on station, watching for me as he had undoubtedly been doing for the few days, waiting for another chance to kill me. I swirled the whisky in my glass, looking at it and considering the afternoon light visible from the windows beyond. It was a foolhardy thought, but part of me wanted to walk outside and attract his attention in order to lure him to me.

That part, the man who had lost his wife just weeks before, did not care about his own safety. But I found that another part still did, although when I asked myself why, I couldn’t provide any satisfactory answer.

I was still having these thoughts when I heard the front door open. It was immediately obvious that Holmes had returned. He bounded up the steps in one of his fits of enthusiastic energy, singing something that I recognized from Verdi’s Otelo, which had premiered in London nearly a year earlier. I was certainly not an opera enthusiast, but Constance and I had attended a London staging at the invitation of friends, and I recalled this theme clearly, as it was repeated several times throughout the performance, before appearing ominously at the end, altered into a darker and maddened jealous heartbeat when Desdemona is strangled. I wasn’t aware that Holmes had seen the opera or knew of the song, and I thought it an odd choice to sing when one was in an apparently ebullient state of mind.

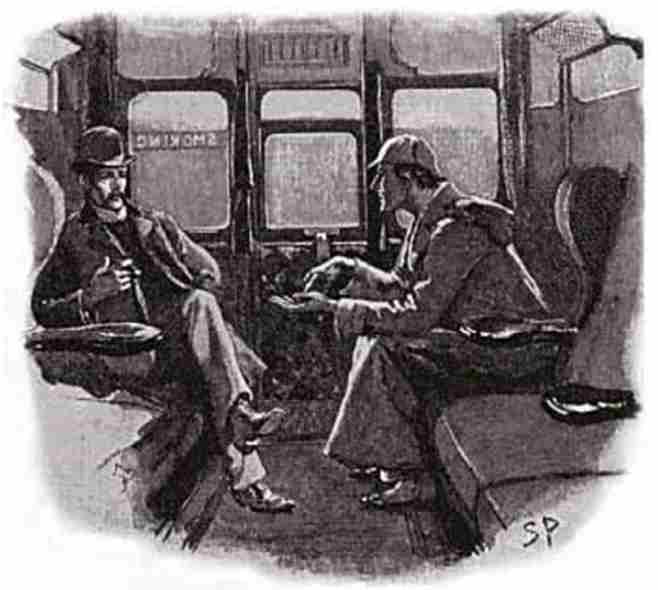

He opened the door and, seeing me, threw a greeting my way while placing a heavy black leather case along the wall behind the door. Then he divested himself of his Inverness and matching ear-flapped traveling cap. Hanging them, he poured himself a brandy and joined me by the fire.

He immediately registered my mood, and his enthusiastic mien vanished in an instant. “My dear Watson,” he said. “What has happened?”

“How do you know that anything has happened?” I asked peevishly. “Might I just be despondent over recent circumstances? I did, after all, spend the morning divesting myself of a medical practice that I worked for over a year to build, all in the hopes of…” I fell silent.

Holmes cast his eyes down. “Your shoe tips are scuffed and the knees of your trousers are unusually and newly worn, as if you’ve been recently crouching on pavement. Your knuckles are freshly scuffed, indicating a fist fight. And most telling of all, there is quite a bit of dried blood on the cuff of your right sleeve. It isn’t difficult. Something has happened.”

I glanced at my arm and saw that he was right, but I felt no need to immediately change my shirt. The stain was like a badge, reminding me of what had happened. “I’m tempted to mention that there was really nothing to those observations at all, as even I would have been able to notice those signs on my own person, if I had bothered to look.” I paused to take a swallow, noting that I had barely consumed hardly any of the whisky since pouring it. Rather, I had sat in thought, merely holding and tipping it back and forth in the dying light from the windows. A glance at the clock showed that it was later than I had realized. “Suffice it to say, I had an interesting afternoon,” I said, “but I’d rather hear first about what made you so happy while running up the stairs.”

He could see that I had no intention of explaining any more before he told his story, so he began. “I have spent the morning and a good part of the afternoon researching aspects of Ian’s background. I began by conferring with various specialized individuals within the government who are aware of the idol, and the threat that it represents. I learned that they have kept regular tabs on it at the Museum, as mentioned by Williams. They were not, however, aware that the Earl had made a substitution and was concealing the real thing in the hidden vault in Essex.

“I then had a meeting with Sir Quintin Havershill at the Museum. He wasn’t a great deal of help, as he had passed the years between the time the substitution was made and now happily believing that the object in the locked chamber was the real thing. He indicated that the responsibility for it rested with Williams, the murdered man, and no one else, so there isn’t another soul that can provide any more useful information. Williams had been with the Museum since the early ‘70’s, obtaining his post straight out of University. He was a quiet man, not given to mixing with his coworkers. He was moderately ambitious, but had refused several upward promotions into other areas, instead remaining at his same level within a sub-department of his discipline, indicating that he would prefer to rise in that area instead of obtaining some easier advancement in another department.”

“That isn’t necessarily an unusual desire to have,” I said. “Perhaps he was more comfortable with his one certain area of expertise.”

“Possibly, if that were the only consideration. But I was able, in the company of Inspector Gregson, to examine Williams’s lodgings in nearby Coram Street. They were quite modest, but he had a small art collection of his own, with several original pieces that would seem to far outstrip his regular wages.”

“Purchased through funds received by a legacy, perhaps?”

“Ah, Watson, you are asking the right questions, but they have already been answered. I cannot impress you enough regarding the concern that the missing idol has caused at the highest levels. When the officials are moved to act, they can accomplish great things very quickly. An examination of Williams’s financial dealings, instigated with great urgency and efficiency by these events, revealed no inheritances that might have accounted for this private collection. But we did learn of the dead man’s bank account, which currently holds a balance of something over £30,000.”

“Good heavens!” I cried, sitting up a little straighter in my seat. “On a Museum employee’s salary? Are you certain that such a sum didn’t come from a rich relative? How could he possibly have saved that much?”

“Because,” replied Holmes, “he was receiving a generous monthly stipend in addition to his modest salary, and had been since 1878. Very soon, in fact, after the statue was first stolen from the Museum by the mysterious John Goins. And who do you think was providing Williams with these funds?”

I began to dimly follow what Holmes was driving at. “Surely it must have been from Ian Finch, the Earl of Wardlaw.”

Holmes slapped the arm of his chair. “Exactly. Ian seems to have conceived the plan of substituting the idol soon after his father arranged to have it loaned to the Museum. Knowing that Williams would be in direct charge of it, Ian bought his servitude. This explains Williams’s reluctance to take a promotion into a different sub-department. He was ambitious enough, but only wanted to rise in a position where he would still receive the extra money and have control over the storage of the sculpture.”

“And to report if or when the substitution was ever discovered,” I added. “That explains why he was so quick to leave yesterday, when he realized that you had spotted it. His first action was to notify his secret employer, the Earl, who then killed him.”

“Oh, Ian didn’t kill Williams, Watson. Did I leave you with that conclusion?”

“What? But surely – ”

“No, there is no doubt that Ian is on the run with the idol, but it is more complicated than that. The murder was committed by that odd little butler, Dawson.”

“When did you decide on this?”