The Post–World War II Metropolitan Landscape

Throughout the American West,

The suburbs have made us all stressed.

They have eaten up farms,

Set off fiscal alarms,

And given the cities no rest.

Chapter Six

Foothills, Two Forks, and the Revision of the Future

A person that started in to carry a cat home by the tail was gitting knowledge that was always going to be useful to him, and warn’t ever going to grow dim or doubtful.

Apollo was a high-performance god. One of his most impressive accomplishments was his design of error-free prophecy in ancient Greece. Responding to a question from a suppliant who wanted to know the future, Apollo would communicate through a set of priestesses who would shout and shriek in an incomprehensible manner. A priest would translate these outbursts into cryptic pronouncements arranged in hexameters. The suppliants would then go off to interpret these predictions. If their interpretation turned out to match the future, then the oracle’s success at prophecy was immediately evident. If the future, however, took a different turn, then the fault lay not in the oracle, but in the inadequate interpretation of the prediction. When, for instance, the oracle seemed to tell the ruler Croesus that he should invade Persia because this would lead to the downfall of a great empire, Croesus made a bad assumption about which empire would take this fall. The messages of the oracle, according to one description, “were always open to interpretation, and often signaled dual and opposing meanings.” The temple at Delphi was destroyed in 373 BCE, not by a grudge-holding recipient of a misleading prediction, but by a poorly foretold earthquake. Rebuilt, it was definitively destroyed several centuries later by the decree of a Roman emperor who seems to have been a risk-taking sort of ruler.2

A millennium or two later, most human beings are reduced to finding their clues to the future in the events unfolding around them. It is a little unnerving to see that events communicate in a manner rather like Apollo’s priestesses: they carry multiple meanings, they require strenuous interpretation, and a good share of the time they are insolubly bewildering. Sometimes they baffle humans by proceeding sneakily through time, unnoticed by those whose destinies they will affect; other times, they confuse people with the equivalent of unintelligible shouts. Events are particularly treacherous when it comes to their unwillingness to be forthright in announcing major change. To take the example closest at hand, when an organization that has consistently gotten its way encounters an obstacle, it is as reasonable to take that obstacle to be a temporary setback as it is to recognize it as a bellwether of enormous and irreversible change.

In hindsight, it is entirely clear that by the 1980s Denver Water had received a generous supply of hints and warnings that its old habits were not going to continue to work. Return to the early 1980s, however, and a different interpretation—that the agency could master new challenges with strategy and persistence, and thus had no need to change its custom—looked like an equally reasonable conclusion. It is not hard to imagine why Denver Water found the second approach considerably more appealing.

In the years 1955 and 1956, two big events with seemingly opposite meanings occurred in western water history. In the much-less-publicized event, the 1955 completion of Denver Water’s Gross Dam, the expectations of business as usual were solidly validated, and the patterns and trends of the recent past continued to flow in familiar and comfortable channels. In the far more famous event, the 1956 decision not to build a dam at Echo Park within the boundaries of Dinosaur National Monument, the well-established expectation that large dams would continue to be built went sailing off a cliff and landed in a heap. For alert observers in the mid-1950s, depending on which event was at the center of their attention, it would have been reasonable to conclude that everything was changing in western water management and just as reasonable to conclude that nothing much was changing. In mid-twentieth-century Denver, the epidemic of uncertain vision that afflicted many who claimed to see the future would have caused even the best ophthalmologist to throw in the towel.

Let us begin with the event that seemed to confirm that the patterns of the past would move smoothly into the future. In 1955, the same year as the first Blue River Decree, the Denver Water Department completed the construction of the most expensive reservoir in its system to that date. Without anything like the controversy that dogged its counterpart on the Blue River, Gross Reservoir—designed to provide storage on the Front Range for water diverted from the Western Slope—was christened with “dignity and beauty” (as the Water Board happily reported about its own party) by Miss Sharon Kay Ritchie, Miss Colorado and future Miss America, who ceremoniously smashed a bottle of Western Slope water against the concrete dam.3 People who attended the Gross Dam ceremony with Miss Colorado would have been perfectly justified in thinking that the building of dams on the Front Range would occur in an entirely congenial and ruckus-free manner, even if diversions from the Western Slope had become the occasion for legal tussles.

Nonetheless, those present at Gross Dam’s christening could not miss the fact that their cheerful ceremony rested on a foundation of human tragedy. A survivor, Harry Artemis, described the calamity that took place four years earlier. On August 24, 1951, Artemis was “working 280 feet above the floor of the canyon, drilling blasting holes in the face of one wall” and “suspended by 60 feet of strong rope tied above me to the rim of the canyon.” A storm raced in that afternoon, and before he and other workers could take refuge under a rock ledge, a lightning strike ignited “32 tons of dynamite on both walls” in “a series of ear-splitting explosions that bore through the canyon’s belly like a bomb.” Artemis and others landed on the canyon floor. “It looked like Korea, only worse,” he remembered, drawing a comparison to the gruesome battlefields that appeared in the news as the dam was under construction. “Blood streaked the rocks. Dazed men were yelling, probing—looking for the dead and injured.”4 Of the 250 men who had been at work on the canyon walls when the lightning struck, 9 were dead among the rubble. Stories of this intensity are not uncommon in the origins of the undertakings that we have veiled and cloaked with the dull term infrastructure. For most Americans who benefit from those systems, the sedative of amnesia has been used to relieve the discomfort that might be delivered by the stories of infrastructure’s martyrs.

Denver Water dedicated Gross Dam on August 2, 1955, without any of the controversy that dogged the dams at Dillon or Echo Park. The highlight of the ceremony, according to a report from the Water Board, was Sharon Kay Ritchie, Miss Colorado and future Miss America, who smashed a bottle of Western Slope water against the dam “with dignity and beauty.”

Exempted from any comparable amnesia, paradoxically enough, was the Echo Park Dam, made famous by the fact that it was never built and thus never brought injury or death to workers. Formally proposed by the Bureau of Reclamation in 1946, the Colorado River Storage Project included a dam and reservoir in a remote area near the border of Colorado and Utah. The principal goal of the Colorado River Storage Project was to hold water in the Upper Basin of the Colorado—to guarantee that the Upper Basin could honor its Colorado River Compact obligations to deliver 7.5 million acre-feet to the Lower Basin every year and to hold water for use in the Upper Basin itself. This particular dam would flood an area within a designated national monument under the management of the National Park Service. The dinosaur tracks and relics at Dinosaur National Monument would not be affected by the dam, but a beautiful area within the monument—Echo Park—would be flooded. For the many organizations that united to oppose the dam, the principle at stake was the recognition of the priority carried by federally designated land preservation. A national park or a national monument should be exempt, by this principle, from serving as a dam site.

The fight over Echo Park is a widely recognized watershed event in American environmental history. As Mark Harvey, the leading historian of this episode, observes, before this battle the Bureau of Reclamation (and, one might add, other agencies developing water on a large scale) “could not easily be challenged by those who lacked technical knowledge of irrigation, hydropower, and cost-benefit ratios.” The dam’s opponents, led by the Sierra Club’s David Brower, knew they could not win their campaign by praising the beauty of the site they wanted to protect. Those who wanted to preserve Echo Park had to develop “an understanding of evaporation rates, the legal complexities of the Colorado River compact, and the economics of large water and power projects.” Since Congress would make the final decision, the best route to success was to give senators and representatives from the North, South, and Midwest reasons to question the economic and engineering rationales for the dam.5

In 1956, after an extraordinary lobbying effort by preservationists, the law creating the Colorado River Storage Project did not authorize the Echo Park Dam. In exchange for stopping the project at Echo Park, environmentalists agreed not to oppose a large dam at Glen Canyon on the Colorado River. This trade-off complicates the calculus of victory in a final assessment of the Echo Park controversy. Still, Harvey sees the defeat of the dam as “a great symbolic victory for the sanctity of the national park system.” It was also a victory that rippled with real consequences for water agencies, as environmental historian William Cronon has explained: “The struggle to stop the dam at Echo Park would become a defining moment in the emergence of a new post-war environmental politics . . . From this moment on, dam-builders would gradually find themselves in ever more defensive positions, so much so that many of their most hoped-for projects eventually became untenable.”6

If the defeat of the Echo Park Dam represented the defining moment, after which dam builders would be in ever more defensive positions, that moment did not shake the complacency of the leaders of Denver Water. As is often the way with large-scale changes, the rising power of what would be called environmentalism was easy to see in hindsight but hard to detect in 1956. Moreover, the central issue of the Echo Park controversy was, in a sense, only secondarily about dams and reservoirs. The “heart of the story,” as Harvey notes, was the “dire threat to the national park system.” There was little reason to think that the defeat of Echo Park Dam would be duplicated for proposed dams in areas that were neither national parks nor national monuments.7

For very good reason, Denver Water’s leaders did not see in the fate of the Echo Park Dam any foreshadowing of the future of their own projects. In the mid-1950s, the scale of the legislative revolution that would take place in the late 1960s and early 1970s was beyond anyone’s prediction. Harvey reminds us of what a different world the West of the 1950s was: “It should be emphasized that this controversy took place long before the ‘environmental revolution’ of the 1960s [and 1970s], and that the opponents of the dam had no legal weapons to block or delay the project.” No advocate in the 1950s could deploy the “environmental impact statements or other legal weapons” that would be “available to a later generation of environmentalists.”8

Echo Park was a very important story, but it was far from an unmistakable demonstration that the conditions of water development had undergone irreversible change. Even to alert observers, the traffic light at the intersection of water development and natural preservation might have turned yellow, but it certainly had not turned red. With the successful and uncontested completion of Gross Dam at the center of their attention, the Denver Water Board proceeded under the impression that there was no reason to stop, and even a reason to speed up.

Although it was located on the Front Range, Gross Reservoir played a crucial role in the whole system of diversion from the Western Slope. If the Water Board could not put the water that traveled under the Continental Divide through the Moffat Tunnel to immediate use, they would have to spill it—release it to flow down the South Platte and beyond the reach of the city. Importing water for the benefit of downstream Nebraskans understandably struck the officials of Denver Water (and the representatives of the Western Slope!) as waste. Thus, the capacity to store diverted Western Slope water on the Front Range, keeping it available for Denver’s needs, was a necessary and urgent element of the agency’s plans. With Denver Water’s future-oriented mind-set, constructing Gross Dam was only one step in the larger enterprise of making sure that there would be sufficient storage on the Front Range to avoid “waste” and to hold enough Western Slope water to meet future demand.

Without those places of storage, owning the rights to water was an abstraction with little material meaning. The complex of major dams built on the South Platte River and South Boulder Creek over the course of the twentieth century—Antero, Eleven Mile, Cheesman, and Gross, plus the holding basins of Marston and Ralston—served as the Water Board’s principal buckets on the Front Range, collectively storing almost 270,000 acre-feet. The massive Dillon Reservoir west of the Continental Divide held nearly that much again. The flow of the water that came from the Western Slope had to be managed in Front Range reservoirs and strategically released by calculations of its abundance and the intensity of demand.9

Once Dillon Reservoir went into operation, the Denver Water Board confronted an unusual problem of overabundance. During the high runoff season of the spring and early summer months, when Denver Water could draw on its direct flow rights to divert a certain flow of water straight from the Blue River into its system without first storing it in Dillon (storage rights for filling the reservoir were applied separately), the agency could deliver more water through the Roberts Tunnel than it could store in its lower South Platte system. What to do? The board sought the remedy in a long-contemplated storage project: a dam at the confluence of the North Fork of the South Platte and the main stem of the South Platte, a site known as Two Forks.10

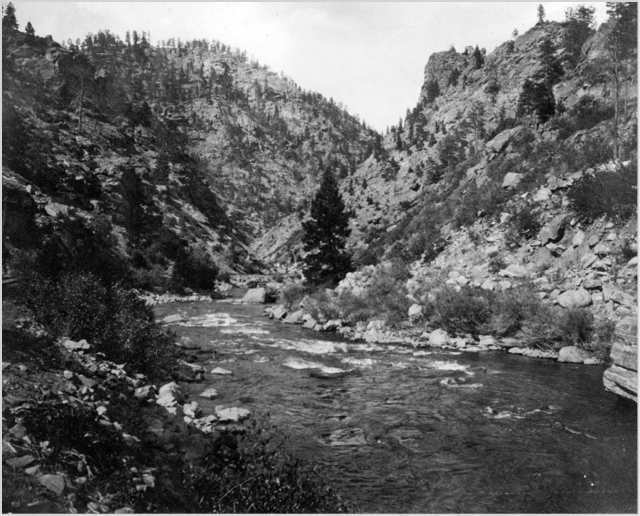

In its topography and geology, Two Forks looks like a model dam site.§§§ A mile and a half below the meeting of two rivers, the canyon pinches in, in a fashion reminiscent of the Cheesman Dam site, creating a narrow gap, nicely sized for a dam, measuring only a hundred feet across at its floor. The floor is free of faults, providing an excellent base for anchoring a dam. George Cranmer, the former city manager of public works who oversaw the construction of the Moffat Tunnel, called it “a perfect damsite” in 1965. Even Daniel Luecke, one of the leading voices opposed to the reservoir, had to agree in 2009 that the spot is “an ideal place to build a dam.”11

§§§ While the site did indeed present the advantage of a narrow canyon, where a dam would back water up into a broad valley, the hydrological efficiency of the project came into dispute. Environmentalists argued cogently that there was a gap between the dam’s capacity for storage and the actual firm yield of water that it would provide. The critics made a convincing claim that for a good share of the time, the reservoir would be less than half full. (Personal communication from Daniel Luecke to Jason L. Hanson and Patty Limerick, December 27, 2010.)

With an initial claim made in 1905 by the Water Department’s predecessor, the Denver Union Water Company, the Two Forks site had been under consideration since the early years of the twentieth century. In 1966, just a year after a devastating flood on the South Platte had rampaged through Denver and other metro area communities along the river, the Bureau of Reclamation put forward a plan for a dam at Two Forks. The dam would be built and operated by the bureau with the understanding that Denver (and its suburban neighbor Aurora) would be the primary beneficiaries of its water storage, but that it would also provide flood control and hydroelectric power generation.¶¶¶ In 1970, an organization called the Rocky Mountain Center on Environment (ROMCOE) responded to the studies undertaken jointly by the bureau and the Denver Water Board. “The project,” the ROMCOE report asserted, “hasn’t been properly treated on an ecological systems basis or on a regional planning unit basis.” Imagining the dam’s consequences triggered alarm over urban and suburban expansion. “In 30 to 50 years will there be nothing but this transplanted urban hustle and bustle?” ROMCOE asked. “We are contemplating the drastic alteration of the personality and character of hundreds of square miles . . . is this [dam] another element of the sprawl of the megalopolis which will be smeared from north to south?” ROMCOE did not take an explicit position on Two Forks, but asked for greater consideration of “fish, wildlife, soil erosion, recreation development, [and] land-use planning.” Within a few years, another controversial project would push the Two Forks Dam out of the center of attention, but between ROMCOE and the objections expressed by mountain residents, several well-staged rehearsals of the dispute over its construction had already been performed.12

¶¶¶ The 1965 flood also spurred Congress to allocate funds for Chatfield Dam, with flood control as its primary purpose, and inspired Denver to create a greenbelt along the river where it runs through the city core in an effort to reduce the potential for damage in any future floods.

In the early 1980s, the intensity of Denver Water’s interest in Two Forks picked up. In the 1983–1984 season, the environmental coordinator for the department’s planning division, Robert Taylor, lamented that Denver “lost about a million acre-feet of spring runoff because there was nowhere to store it.” This state of affairs wore on the patience of managers who wanted to capture every drop they could. A dam at Two Forks could capture much of that water and hold it for use in dry times. Planners found an additional advantage in the fact that the Forest Service and the Denver Water Board owned most of the surrounding land, lessening the prospects for opposition from prior residents.13

While its advantages as a dam site struck advocates as unmistakable, Two Forks remains as dam free as Echo Park. Unsubmerged, the place stands as a monument to a major victory for the environmental movement, a crucial exercise of federal support for the preservation of natural settings, and a decisive setback to Denver Water’s ambitions. For the better part of a century, the Denver Water Board had worked to orchestrate the resources of several watersheds encompassing roughly thirty-one hundred square miles on both sides of the Continental Divide.14 With extraordinary determination, its engineers and workers had bored miles of tunnel through the Colorado mountains, impounded hundreds of thousands of acre-feet of water, laid thousands of miles of pipe, dug hundreds of miles of canals, and installed thousands of valves to secure a reliable and abundant water supply for the people of Denver. For all this energetic activity, in the last half of the twentieth century, a new set of obstacles, hurdles, restraints, and regulations appeared in Denver Water’s path.

The South Platte River’s flood in June 1965 left some dramatic wreckage in its wake, such as this pileup on West Alameda Avenue. It also prompted the US Bureau of Reclamation to put forward a plan for a dam at Two Forks, a site that the Denver Water Board and its predecessors had been interested in since the first years of the century.

Some of these new elements had figured in the story of the Blue River diversion, but Denver Water had still achieved its primary goals in that episode. In the struggle over Two Forks Dam, Denver Water would finally confront opposition that it could neither overpower nor outmaneuver. Reflecting on the fact that the Two Forks Dam would not be built, the Environmental Defense Fund’s Daniel Luecke concluded that “we have at this point seen the end of the big dam era.”15 The shift begun at Echo Park had come to a definitive conclusion at Two Forks.**** As a lasting demonstration of the scale and impact of changing American attitudes toward the use of natural resources, the defeat of Two Forks signified beyond doubt that the rules had changed, and the big dam era was indeed over.

**** The end of the big dam era was signified by a definitive shift in public attitudes toward major impoundments, not by an instant moratorium on all dam projects. In the decades following the defeat of Two Forks, two additional big dam projects were completed. The Army Corps of Engineers built the Seven Oaks Dam on the Santa Ana River in southern California, a project that was approved by Congress in 1986 and completed in 2002. And the Bureau of Reclamation completed the Ridges Basin Dam in southwestern Colorado in 2007, part of the Animas–La Plata project that was approved by Congress in 1968 to meet US obligations to the Ute Mountain Ute and Southern Ute tribes that date to 1868. There are currently no additional big dam projects under construction in the West.

Why, in the 1980s, did the Denver Water Board not try to alter its course and steer around these new obstacles? For an agency operating under the mandate to provide adequate water for the citizens of Denver, changing its course could well sound like a synonym for betraying its mission. Exemplifying that point of view, Denver Water’s chief legal strategist and public voice, Glenn Saunders, greeted the emerging shift in attitudes and policies with neither cheer nor submission. Earlier, in the late 1950s, as Congress began deliberations on a bill for the protection of wilderness areas, Saunders found the whole idea preposterous: “How,” he asked, “can any right-thinking American give serious consideration to wilderness legislation which will hamper the water development necessary to unlock [the West’s] vast potential?”16 The federal government, he said on behalf of the board to a Senate committee in 1959, was wavering in its willingness to grant and lend money for reclamation projects. And now federal officials were pressuring the Denver Water Board to change its operations to leave more water in rivers for recreational use and for the needs of aquatic life. The US Fish and Wildlife Service, a part of the Department of the Interior, had demanded that the board maintain a minimum stream flow of thirty-five cubic feet per second in the Williams Fork in order to sustain trout. Such fisheries generated significant income for the local community and the state as a whole. Unmoved by these appeals, Saunders felt that the fish could just figure out a way to get by with two cubic feet per second. As always, to Saunders, Denver Water’s job was to provide water for the city, a job that left no room for concerns about the Western Slope’s fortunes or fish, and that translated the demands of federal agencies into unwelcome nattering.17

So Saunders was finding federal intrusions to be an irritation in the 1950s. To use colloquial but emphatic phrasing, he hadn’t seen anything yet.

The escalation of environmental regulation and litigation was truly a change of eras for the nation and particularly for the American West. Not long ago, western historians took part in a furious fray over whether the year 1890, long designated as the end of the frontier, actually represented a major watershed, dividing a frontier West from a postfrontier West. Even as professorial feathers and fur flew in this arcane spat over chronology, evidence was accumulating that a far more significant divide in time was taking shape. The passage of the environmental laws of the 1960s and 1970s divided the phases of eestern history in the most dramatic and literally down-to-earth way. Consider the major components of this revolution, which, taken together, amounted to an entirely new set of ground rules: the Wilderness Act of 1964, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968, the Clean Air Act of 1970, the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970, the Clean Water Act of 1972, the Endangered Species Act of 1973, and the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976.

State government played its own role in this revolution. In Colorado, the environmental spirit of the times led the legislature to pass HB 1041, a law that gave local governments significant power to regulate “areas and activities of state interest” (and is therefore often referred to as the Areas and Activities of State Interest Act). The act empowers local governments to exercise some authority over the development of resources within their jurisdiction, thus putting a check on the Denver Water Board’s ability—which the city agency had enjoyed since the passage of Article XX in 1904—to reach beyond the city borders for water without the approval of the impacted citizens. The Denver Water Board challenged the law in court, claiming that it amounted to an unconstitutional delegation of power to local governments, but in 1989 the Colorado Supreme Court finally and decisively upheld HB 1041.18

Whatever case old-school historians tried to make for the transformation wrought by the end of the frontier in 1890, that transformation was dwarfed by the impact of this extraordinary episode of lawmaking in more recent times. And when it comes to choosing the prime example of the game-changing consequences of these laws, the story of the Denver Water Board easily qualifies for the list of the finalists.

Dams, reservoirs, and tunnels through mountains, and the fights and struggles they trigger, have a certain scale and drama. By contrast, a person who would like to designate water treatment plants as gotta-have-it items in the cultural literacy list of the informed citizen will have to work vigorously on her sales pitch. Still, nothing is more important to citizen well-being than these seemingly dreary facilities. Denverites may have happened on to the good fortune of relying on a water supply that comes more or less directly from the pure snows of the Rocky Mountains, with very little of the pollution that rivers pick up as they flow through farmlands, towns, cities, and industrial areas. Denver’s situation is, in other words, very different from New Orleans’s or Saint Louis’s. But even Denver’s water requires treatment to make it reliably safe and potable.

Despite earnest and prolonged efforts to build adequate facilities, the Water Board’s ability to process water struggled to keep pace with public demand. In the 1970s, growth in the metropolitan area stretched to its limit the department’s capacity to treat raw water. Hot July days in 1972 and 1973 pushed water demand beyond the treatment system’s recommended capacity of 460 million gallons per day, spiking to a record 506 million gallons on July 6, 1973, as Denverites coped with a high of 103°F. Thirsty customers drew enough water through the pipes during these heat waves to deplete holdings in the reservoirs and raise fears among water managers that a day might come—and soon—when they would not be able to treat enough water to meet peak summer demand.19

In its customary manner, the Water Board responded to the threat of shortfalls with a plan to expand the system. The board proposed a $160 million bond issue that would finance the construction of a reservoir and a treatment plant in the foothills southwest of Denver. With the Strontia Springs Dam situated in Waterton Canyon, a reservoir would settle water diverted from the South Platte before it moved to the anticipated Foothills Water Treatment Plant near Roxborough Park south of the metro area. The bond measure was defeated in 1972, in large part because environmentalists saw the proposed 500-million-gallon-per-day plant—which would give the water agency a capacity to treat far more water than it actually had in storage—as a sneaky prelude to building Two Forks Reservoir, which they worried would mean increased diversion from the Western Slope and more sprawling growth around the metro area.20

After another scorching summer, the Water Board tried the measure again in 1973, this time with a promise that the initial plant would be built to treat only 125 million gallons per day, with expansion to its full 500-million-gallon capacity coming only as needed in later phases. The Water Board’s promises reassured enough voters to win approval for the bond measure in the fall of 1973, but it did not satisfy all of the agency’s critics. Even if it started small, critics were quick to observe, the Foothills Plant was not designed to stay small. The dam at Strontia Springs and the tunnel conveying water from the reservoir to the plant were going to be full-size from the start, making the later expansion of the plant itself look foreseen and intended. A big question hovered over Foothills: since an increase in Denver Water’s capacity to treat water would exceed the current raw water supply, where was the additional quantity of water for the full-size plant going to come from? With the answer to that question left hanging, the Foothills Plant looked more and more like the entering wedge for a much larger project—one that would include bigger diversions from the Western Slope—in the near future.21

In the worldview of Denver Water’s leaders, all their foresighted anticipation of future needs should have elicited not condemnation, resistance, and opposition but gratitude, support, and applause. In the twenty-first century, it may seem that these leaders confronted an earthquake in public opinion and misread it as a few inconsequential tremors. In truth, the scale of this shift in attitudes toward growth was almost beyond comprehension. For the better part of two centuries, Americans had looked at the American West and found “manless land calling out for landless men.” Getting more people into the West—promoting the region, advertising its resources, recruiting settlers to occupy more homes—served as the operating definition of progress. In the middle of the twentieth century, the suggestion that the definition of progress was on the verge of reversing, recasting the formerly welcomed increase in population as a problem, was psychedelic (to use the valuable term that would soon emerge from the counterculture). But changing attitudes toward growth, along with the new powers given to federal agencies, brought into being novel alliances and oppositions that challenged the inherited definition of progress.

The extraordinary new environmental laws were the most important—and mystifying—manifestation of this changed world. Given the warm feelings that many members of Congress have for the spotlight, it is a temptation to think of the occasion of passing a law as the conclusion of the main story, with a less important epilogue trailing behind and trudging through the bureaucratic process of putting the law into practice. A more realistic understanding of innovative legislation emphasizes the implementation of the law and reduces the story of the law’s passage to a prelude. No one, in other words, knows exactly what a law is going to mean until it has been applied on the ground level, until earnest bureaucrats have tried to exercise the powers seemingly granted to them by the law, and until individuals and groups who disagree with the bureaucrats’ interpretation of their mandate and power have talked to reporters, rallied fellow citizens, hired lawyers, and awaited and accepted the decisions of judges. Denver Water’s efforts to build the Foothills Treatment Plant and the Two Forks Dam thus offer case studies of vital importance to Americans trying to figure out how the 1960s and 1970s environmental laws had transformed their nation.

As our first step into the labyrinth of implementation, we begin with the recognition that the phrase federal government is a term that struggles to hold together a multiplicity of agencies and bureaus that do not always take joy in each other’s existence. In order for Denver Water to get permission to build the Strontia Springs Dam and the Foothills Water Treatment Plant, five federal agencies had to say some version of yes. This meant that every one of those agencies had to reach agreement, not just with the Denver Water Board, but with each other.

The first two agencies were pulled into the controversy because the dam and the reservoir would occupy twenty-seven acres of land under the jurisdiction of the US Forest Service (USFS) and twenty-two acres of land administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). With the Echo Park comparison in mind, it is important to note that the Foothills project did not involve land designated as a national park or national monument. On the contrary, both the USFS and the BLM officially operated as multiple-use agencies, so the sanctity of the national park system, the principal issue of Echo Park, would not be raised. For the project to be built, both agencies had to grant right-of-way permits. Issued without controversy in the 1960s, those permits had expired and needed to be reissued. Here is a fine indicator of the sharp difference between two eras: the National Environmental Policy Act had become the law of the land in 1970, and so the reissuing of these permits had, over the passage of just a few years, become a vastly more complicated process, requiring what was sure to be a detailed, closely inspected, and vigorously disputed environmental impact statement (EIS).22

At the center of the regulatory transformations taking shape in the 1970s was the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), created in 1970 by President Richard Nixon (note, again, the timing of the Foothills initiative, with the bond issue passed in 1973 while the EPA was still in institutional infancy). For several years after its origin, the EPA was an idea waiting to be turned into practice and substance. No one had more than an informed guess of how extensive its powers would be, nor how much autonomy its officials would be given to exert those powers in the complicated world of national and regional politics.

When the BLM and the USFS moved toward granting right-of-way permits, the EPA took the occasion to exercise its new powers. Invoking Section 309 of the Clean Air Act of 1970, the EPA brought in another federal organization, the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), which is part of the Executive Office of the President, to review the decisions. In making its case to the CEQ, the EPA challenged the validity of the studies of the BLM and the USFS on grounds that might, at first, seem strangely unconnected to a water project.†††† The Foothills project, EPA argued, “would make the attainment and maintenance of national ambient air-quality standards in Denver more difficult and perhaps impossible.” How, specifically, did the EPA connect a project in storing and treating water directly to damaged air quality? EPA officials found the connection self-evident: “providing water would encourage growth and urban sprawl” and thus recruit more Front Range residents to drive their automobiles hither and thither, befouling the air as they visited, shopped, transported offspring, commuted, worked, and pursued diversion and entertainment.23

†††† This sentence is a stunning example of the principal sorrow of writing environmental history in the last fifty years. Using the full name of federal agencies is cumbersome, leaving only the alternative of acronyms. An apology for inadvertent literary injury nonetheless seems in order.

Another of the new environmental laws brought another federal agency into this scrum, giving the EPA a hold on the permitting process. Section 404 of the Clean Water Act of 1972 required a special permit when the construction of a dam involved inserting fill material into a waterway. The Army Corps of Engineers held authority over the issuing of this Dredge and Fill Permit (commonly, if not creatively, referred to as a 404 Permit by the bureaucratically sophisticated). However, subsection 404(c) gave the EPA the authority to veto any Dredge and Fill Permit issued by the corps (following the pattern, such vetoes are unimaginatively called 404(c) Vetoes). When the corps moved to issue such a permit for Strontia Springs Reservoir, an integral component of the Foothills complex, EPA regional administrator Alan Merson objected, exclaiming that the project’s planned capacity was so out of scale with Denver’s needs that building it was akin to trying “to kill a flea with an elephant gun.” Aligning himself with the environmentalists who perceived Two Forks Reservoir as the unmentioned elephant (certainly not the flea) in the room, Merson threatened to kill the whole Foothills project by issuing a 404(c) Veto of the Dredge and Fill Permit issued by the corps.24

Toward the end of the queue of jockeying agencies was the US Fish and Wildlife Service. A much-amended law originally passed in 1934 required federal agencies to consult with the Fish and Wildlife Service on decisions that impacted the fish and wildlife under its purview. This meant that the well-being of aquatic organisms had to be factored into the plans for Foothills, particularly in terms of the minimum stream flows required to keep those sensitive creatures from going belly-up.25‡‡‡‡

‡‡‡‡ The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission was the sixth agency with a hand in this permitting process, but really, the reader’s patience has been sufficiently tried already.

“When we try to pick out anything by itself,” famed preservationist John Muir once said, “we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.”26 Here, in a rather different sense than Muir had intended, was the central lesson of this new era. To adapt Muir’s quotable line to Denver Water’s point of view: try to pick out any project by itself and you’ll find it connected to a censorious and disapproving federal agency, to an adverse environmental impact, to a chain of consequences that environmentalists will find reprehensible, to big trouble in public relations, and to a tower of paperwork.

Facing an array of federal agencies newly supplied with an expanded and restocked tool chest of regulatory legislation, the Denver Water Board’s proposal for a new treatment plant had appeared, depending on your point of view, with the best or the worst possible timing. Here, arriving like a precisely timed train at a station, was a prime test case for defining what the new environmental regime was going to mean in down-to-earth practice. Never before had the board’s fortunes (like the fortunes of thousands of other such agencies around the nation) been subject to so much regulatory and legal oversight.

Feistier than many of its counterpart agencies, the Denver Water Board responded to the EPA’s veto threats by questioning the authority of federal agencies to determine local land-use priorities. Even if the EPA’s premise proved accurate and an increased water supply inherently and inevitably led to undesirable growth—even then—the board asserted that decisions over resource use were properly the responsibility of the local government rather than unelected agency officials. The issue, in other words, had acquired an interesting dimension of contested federalism, as Denver Water undertook to assert the rights of municipalities and states in a world of expanding federal power.27

As vexatious as Denver Water was finding its dealings with federal agencies, at least those entities had been called into being by Congress and presidents, placed within more or less defined boundaries, and structured into official hierarchies and chains of command. Considerably more flummoxing was the proliferation of environmental groups, brought into being by citizen activists and proving to be capable of putting up very effective fights. The president of the Denver Water Board Charles Brannan offered a memorable dismissal of his environmentalist opponents: “Negotiations with people who have no authority in the matter and whose agreement would be utterly unenforceable in any administrative or legal form would be without purpose and be an indefensible waste of public funds.” While there is no reason to admire his intransigence, only those who have had their sensitivities surgically deadened can avoid a moment of empathy for Brannan’s frustration in deciphering a disorienting new world. He and his colleagues were now encountering peppy groups of people who gathered at coffee houses, living rooms, trailheads, natural food stores, art galleries, bookstores, and various public meeting areas, who formed themselves into teams, committees, and communities, and who then fought Denver Water like banshees. How was an accomplished and well-established utility in its mature years to take seriously these “people who have no authority in the matter”?28

One way to deal with them was, of course, to sue their pants off.

The Foothills controversy produced two suits in federal court. The first one, filed by Denver Water in US district court in Denver, began by rejecting the conditions of the BLM permit as “unacceptable and illegal.” Since the agency held legal rights to the water that would be stored at Strontia Springs, Denver Water’s attorneys asserted, no federal agency could put stipulations on its use or release. The second suit, brought by a coalition of environmental groups in US district court in Washington, DC, claimed that Denver Water’s plans were in violation of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (known by the clunky acronym FLPMA), a law that codified an emphasis on conservation goals in the BLM’s management, and the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970 (NEPA), a law that specified a process for studying and mitigating environmental impacts.

The stakes of the litigation escalated dramatically on August 22, 1978, when the Denver Water Board amended its complaint by alleging that a coalition of environmental activists and federal officials had illegally conspired to “impede, delay, and prevent” the Foothills project. The board named fourteen specific environmental groups and seventeen individual federal officials as conspirators and asked the judge to assess $36 million in damages against them. At the top of the list were EPA regional administrator Alan Merson and his deputy, Roger Williams, whom the Water Board singled out for $3 million in damages.29

At this point, the Foothills squabble acquired its greatest national significance. Environmentalists feared that if the Water Board’s complaint was upheld, the precedent would permanently undermine NEPA, allowing large institutions to silence antagonistic environmental groups through the threat of a catastrophic lawsuit.30 Such a judicial finding, so early in the life of the new environmental law, would have had enormous consequences for the whole matter of public participation in the decisions of federal agencies. By declaring that the environmentalists’ opposition to the Foothills Plant rendered individuals and groups punishable and liable for the damage they had allegedly inflicted on the agency, Denver Water had aimed a sharp kick at the First Amendment.

With the permitting process inching through lawsuits and red tape, Denver Water officials exercised their own free speech, ominously declaring that delay and uncertainty would have grim consequences for Denver’s neighboring communities. Reluctant to take on any new service obligations, in June 1977 the board moved to impose lawn-watering restrictions on its customers and cap the number of new residential taps outside the city at only fifty-two hundred per year, meaning that Denver had cut by a third the number of customers to whom it would normally have extended service. This constraint seemed to echo the Blue Line, sending a shock through the metropolitan area’s economy.31

As homebuilders and suburban officials looked ahead to restricted water services, they pressured the EPA to find a resolution. The environmental groups who had filed the lawsuit in US district court in Washington were short on money, and uncertain of their chance for victory in court. The regional staff of EPA, meanwhile, was feeling out the limits of its authority, uncertain exactly how far its powers extended. While the Clean Water Act did give the young agency the power to block the Foothills project with a 404(c) Veto, all of the interested parties were well aware that the EPA had never yet actually exercised that power. These circumstances, combined with another scorching summer in 1977 that again taxed Denver’s water treatment system to its limit, gradually created a receptivity to negotiation. The Denver Water Board was the most resistant to the idea, and this led to a turn of events that at once broke the usual rules of proper mediation and also made the mediation successful.32

Theory required that mediators be scrupulously neutral. Stepping forward as the prospective chief negotiator, Colorado congressman Timothy Wirth was already known for his longstanding support of the Foothills project. Rather than derail the negotiation, however, Wirth’s unconcealed position proved to be a key asset. The Denver Water Board expected Wirth’s inclinations to work to their benefit, thus leading them to drop their resistance and agree to take part in the negotiations. Wirth, moreover, was indefatigable in his preparation, engaging in multiple consultations before he tried to convene any of the antagonists in a larger conversation. And then, in another inspired move, Wirth undertook a first round of negotiation with the three principal contestants: the Environmental Protection Agency, the Army Corps of Engineers, and the Denver Water Board, shepherding those three to an agreement before bringing in the Bureau of Land Management, the Forest Service, the Fish and Wildlife Service, and the environmental activists. While this phasing of participation risked arousing the resistance of the parties left out of the first round, it also made it possible to work through the most difficult conflicts with fewer participants and also to create a momentum that would make it hard for any one official or agency to run the risk of condemnation as the recalcitrant and bad sport who chose contention over problem solving.33

In the Foothills Agreement, finalized just after the new year in 1979, the Water Board made important concessions in exchange for the opportunity to build Strontia Springs Dam and the Foothills Water Treatment Plant. The Army Corps of Engineers would issue the necessary Dredge and Fill Permit, and the EPA would not object. The permit would, however, carry requirements for both a new Denver program in water conservation and also for efforts to mitigate the impacts of the project. The board agreed to give more attention to public opinion through the creation of an advisory committee. Both the suit brought by the environmentalists and the suit brought by Denver Water would be ended, and Denver Water would admit “that the environmental defendants have asserted their opposition . . . in good faith and within their Constitutional and statutory rights,” and were thus “not proper parties to this litigation.” The agency, moreover, would pay for the environmentalists’ attorneys’ fees. When and if Denver Water proposed another big project, the permitting process would require not just an EIS for that particular project, but a systemwide environmental impact statement, assessing all of Denver Water’s facilities and structures.34

Completed in 1983, the Strontia Springs Reservoir in Waterton Canyon settles water diverted from the South Platte before conveying it to the Foothills Treatment Plant.

Despite the concessions to the environmentalists, the board had achieved its goal of expanding its system with the Foothills Treatment Plant and the Strontia Springs Dam. In June 1979, they signaled their satisfaction with this outcome by easing the moratorium on new taps, increasing by eighteen hundred the number the agency would install to seven thousand annually. When the plant came online in the summer of 1983, the board eased the watering restrictions that had been in place since 1977.35 Into their future battle over Two Forks Reservoir, the leaders of Denver Water would carry the lessons they drew from the events of the Foothills campaign, lessons that did not include methods and techniques for the graceful acceptance of defeat. On the contrary, the lessons of Foothills for the Denver Water Board matched the lessons of the Blue River Decrees: an organization facing opposition and frustration could prevail over these afflictions by threatening severe consequences if its demands on behalf of the public were rejected, submitting to negotiation, and in the end making a concession or two. Even if the pursuit of the goal had to follow a circuitous route, the agency had secured permission and built the treatment plant. In 1979, the Denver Water Board had managed to postpone a full reckoning with the changed world of federal authority over local water operations and with the remarkable rise in influence of environmental groups.

Like many twenty-first-century Americans, the leaders of the Denver Water Board in the last decades of the twentieth century held assumptions, derived as much from stereotype as from evidence, that the stances of the two major political parties toward development and environmental impact were unmistakably distinct and even opposite. Despite the fact that much of the legal framework for the environmental revolution—including the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act, and the executive order creating the EPA—bears the signature of Republican president Richard Nixon, the Republican victory in the 1980 presidential election seemed to signify the return of a friendlier federal stance toward resource development. The Denver Water Board saw a good omen in President Ronald Reagan’s appointment of two Coloradans to key environmental posts in his administration, naming James Watt as secretary of the interior and Anne Gorsuch as EPA administrator. The board therefore made an approach to authorities in Washington, DC, testing out various ideas for projects.

When the Foothills Treatment Plant came online in 1983, it increased Denver Water’s capacity to supply water to household taps throughout the metropolitan area. Although its completion marked the end of one controversy for Denver Water, it was soon followed by a much larger controversy over the Two Forks Reservoir.

They had plenty to talk about, with several projects on the drawing board in addition to Two Forks. In 1963, the Water Board had filed for additional water rights in the Williams Fork basin with the plan of diverting the water into an enlarged Moffat collection system. And in 1968 and 1971 they had filed for a suite of new water rights on the Colorado River, Piney River, Eagle River, Gore Creek, and Straight Creek. The Eagle–Piney, Eagle–Colorado, and East Gore projects, as they were individually known, would collectively bring into being an elaborate series of new reservoirs and tunnels on the Western Slope that would convey roughly 250,000 acre-feet of water (about the size of another Dillon Reservoir) under Vail Pass and through Roberts Tunnel into the South Platte, where the water might be stored in the imagined Two Forks Reservoir.

The fact that the US Forest Service, cheered by environmental groups and supported by the courts, was maintaining a stiff resistance to the Williams Fork enlargement might have discouraged water suppliers with less pluck than Denver Water. The fact that Congress, at the behest of Colorado’s environmental community, had created the large Eagles Nest Wilderness Area in 1976, smack in the middle of the proposed Eagle–Piney, Eagle–Colorado, and East Gore projects, might have seemed like a deal breaker to less spirited water agencies. In hindsight, it is easy to wonder why the Denver Water Board did not interpret this swell of opposition as a warning shot across the bow from an environmental community carrying growing clout. But interpreting oracles is a tricky business, and when the Denver Water Board reflected on its successes with Foothills and the Blue River, it was just as reasonable to anticipate the agency’s eventual triumph through strategy and persistence. Despite daunting challenges, the Denver Water Board pressed its case confidently in Washington and at home.36

Looming largest of all of the Denver Water Board’s endeavors was Two Forks Reservoir. Colorado’s governor Richard Lamm tried to forestall another round of bitter conflict by offering to bring the contestants together for a negotiation. The Denver Metropolitan Water Roundtable assembled a Noah’s Ark of thirty stakeholders in the metro area’s water future: “county commissioners, suburban mayors, municipal water suppliers, South Platte irrigators, land developers, Colorado River counties and towns, and environmental organizations” were all represented, recalled Daniel Luecke, himself one of the two environmental delegates offered a seat at the table. The representatives of the environmental community had been chosen from a coalition of groups operating together as the Colorado Environmental Caucus,§§§§ who took as their mission the task of looking for alternatives to Two Forks “that would provide comparable amounts of water by less environmentally damaging means.”37

§§§§ A striking range of organizations from the national to the local level came together in this informal collaboration. By the time the controversy over Two Forks had fully run its course, the caucus had counted among its members the National Wildlife Federation, Colorado Mountain Club, Trout Unlimited, Environmental Defense Fund, League of Women Voters, Wilderness Society, Sierra Club, Sierra Legal Defense Fund, American Wilderness Alliance, Friends of the Earth, Colorado Open Space Council, National Audubon Society, Concerned Citizens for the Upper South Platte, Western River Guides Association, Colorado Whitewater Association, Colorado Environmental Coalition, Western Colorado Congress, and more. Daniel Luecke was the head of the Environmental Defense Fund’s Rocky Mountain office, and the other delegate to the roundtable, Bob Golten, was an attorney with the National Wildlife Federation.

Beginning its meetings in the winter of 1981–82, the Denver Metropolitan Water Roundtable was given the ambitious goal of achieving consensus on the future water supply for the area. Unable to get the environmental representatives to endorse Two Forks, Denver Water tried, energetically but unsuccessfully, to force the environmentalists out of the roundtable. The efforts of the Colorado Environmental Caucus to win support for alternatives to Two Forks, meanwhile, had hit the brick wall of Denver Water’s opposition. Satisfactorily stymied by 1983, the roundtable took a break.38

With an unimpressive record on achieving consensus, the roundtable had, nonetheless, produced very significant results. The Colorado Environmental Caucus had come into its own with major gains in expertise, strategy, and public visibility. The broad environmental coalition had—much to Denver’s chagrin—assembled a staff of credentialed and qualified experts, capable of credibly challenging the Water Board’s calculations and projections with sophisticated quantitative methods of their own.39 Denver did not sit idly by and allow itself to be outflanked by collaboration. The Water Board reached out to old rivals to build its own alliances with the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, the Colorado River Water Conservation District, and suburbs throughout the metro area.

The Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District did not oppose the construction of Two Forks, fearing that the alternative was metropolitan municipalities buying up—and drying up—agricultural water rights. And, after extensive negotiations, the Colorado River Water Conservation District traded neutrality toward Two Forks for Denver’s support of several Western Slope projects. All three water agencies took the occasion to settle longstanding water rights disputes, including agreements on Denver’s Eagle–Piney claims and a consideration of the Western Slope’s desire to build a pumpback from Green Mountain Reservoir to Dillon Reservoir, demonstrating that intractable disagreements can turn into valuable negotiating chits when the right moment comes along. But the most consequential alliance that Denver built in support of Two Forks was with the suburbs, which joined together with the Water Board to pursue the construction of the reservoir.40

Denver’s work to build alliances with its suburban communities led to the Metropolitan Water Development Agreement in 1982. This pact established that the suburban water providers would join with Denver in paying for the mandated systemwide environmental impact statement that, by the terms of the Foothills Agreement, had to occur before Two Forks or any other big project could get under way. The Metropolitan Water Providers, representing this coalition of suburban municipalities and water districts partnering with Denver, would pay 80 percent of the costs and the Water Board would pick up the remaining 20 percent; water from the project would be divided in those same proportions. Only a generation after the Blue Line controversy, the agreement marked an extraordinary moment of collaboration in a relationship historically structured by distrust.41

The new alliance between Denver and its suburbs responded to several trends that were reshaping the dynamics of the metro area. All over the nation after World War II, major cities found themselves embedded in rings of suburbs. As Denver grew, the suburbs dramatically outpaced the city in growth. Political scientist Brian Ellison summed up the numbers: “In 1940, 28% of the metropolitan population lived outside Denver. By 1960, that number climbed to 49% of the total metro population; by 1986 it was 75%.” This striking shift in proportions was certain to rattle preexisting arrangements and allocations of authority and influence.42

For several decades, annexation served as the key process for setting the terms of the relationship between Denver and the growing communities in its vicinity. People in new areas of residential development had two big reasons for pursuing annexation to the city. First, Denver absorbed the debts of the special district governments of those areas; this local debt was diluted in the much larger (and growing) pool of Denver taxpayers. Second, unless a suburban municipality had negotiated favorable terms for a permanent water service agreement after the adoption of the 1959 Denver City Charter, the Denver Water Board charged customers outside of the city limits a higher rate for water; annexation thus made water more affordable and spared the annexed community the burdens of developing its own source of supply. While annexation was a process conducted by the city government, water was an important element of the transaction, and thus, as Brian Ellison remarks, “It was through this process that the Denver Water Board became embroiled in the annexation debate.” In the 1950s and early 1960s, in the push to build new, large water-supply projects, Denver Water would “deny suburban areas access to its water.” Strategically, “the board then blamed the denial on shortages of water supply, which could be solved by the development of the project under consideration.” These episodic moratoria played a significant role in the antiannexation movement by “infuriat[ing] suburban communities and increas[ing] suburbanites’ mistrust of Denver.”43

Water was not, however, the most significant factor shaping the workings of annexation in the Denver metropolitan area. “No discussion of the settlement patterns of the American people,” the great historian of suburbia, Kenneth Jackson, declared, “can ignore the overriding significance of race.” The desire of twentieth-century white Americans to live in places sequestered from the racial and ethnic diversity of core cities was a driving force for the growth of suburbs. As urban historian Jon Teaford put it, “The political boundaries, as well as social, economic, and ethnic frontiers, divided urban America.”44

As historian Frederick Watson summarized a complicated story, “When the black population began to expand in the early 1950s, the Denver School Board started segregating black students and teachers in certain schools in the district.” Over the next years, the Denver School Board, in Watson’s words, “employ[ed] a policy of racial containment and stabilization that was designed to prevent white middle-class flight from the city.” In 1969, after various protests against the inferior education provided by the segregated schools, African American parents filed the lawsuit Keyes v. Denver School District No. 1. With a decision in June 1973, “the [US] Supreme Court for the first time ordered busing for a city outside the South” and “served notice that henceforth even subtle racial discrimination could be a dangerous game for a northern school district to play.”45

Desegregation and busing triggered consequential changes for local annexation practices. Traditionally, annexation brought new areas into the Denver Water Board’s service area and into the school district of the City and County of Denver. As Franklin J. James and Christopher B. Gerboth summed up the point, “Suburban parents’ fear of becoming involved in the city’s court-ordered school busing program was a potent source of suburban opposition to Denver annexations.” Led by a local lobbyist, Freda Poundstone, suburbanites who did not want their children to be subject to court-ordered busing supported a constitutional amendment that made it far more difficult for Denver to annex its neighbors, requiring that “annexations be approved by voters in the county from which the annexation is being made.”46 The passage of the Poundstone Amendment in 1974 effectively ended Denver’s ability to annex territory from the surrounding counties.

The Poundstone Amendment also carried the consequence, unintended by its proponents, of excluding unannexed suburban areas from the Denver Water Board’s core area of service. This, in the big picture of post–World War II urban history, created quite a paradox. Teaford succinctly sums up the widespread pattern of the time: “During the postwar era, suburbia’s gain was the central-city’s loss.”47 However, Denver’s situation presented a major twist on that plot: with significant holdings in water rights and with a vast infrastructure that would be impossible to duplicate, the city held assets that the suburbs could not match.

Since few suburban communities had the financial ability to build their own water systems, contracts with the board provided one of their limited choices. With the board steering by the charter’s required priority of supplying customers within the city, these contracts imposed higher rates on the communities outside the city. And suburbanites recognized that if drought occurred, then their contracts could prove precarious. This context of uncertainty lay behind the Metropolitan Water Development Agreement of 1982 and the unusual experiment with regional cooperation it represented.48

As the metropolitan area came together in support of Two Forks, the environmental community remained unified in its efforts to stop the dam. The Colorado Environmental Caucus meticulously identified and appraised the unique natural features of the Two Forks site, made inventories of plant and animal species, and projected what would become of these organisms if a dam submerged the canyon. Ecologists warned that inundation would jeopardize local populations of trout, bighorn sheep, whooping cranes, sandhill cranes, and piping plovers. Peregrine falcons might lose nesting habitat. While the falcons had abandoned local aeries since their initial drop in population from the effects of DDT, they had been making a comeback, and they might repopulate those aeries if a reservoir did not interrupt the process.49

Among the species catapulted into celebrity status in the environmental conflicts of the late twentieth century, the Pawnee montane skipper joined the snail darter fish in Tennessee and the spotted owl in the Pacific Northwest as an iconic creature with consequence far beyond its tininess. Measuring less than an inch long and easily mistaken for a moth by the uninitiated, the Pawnee montane skipper exists nowhere else in the world but the Platte Canyon. Because of its very limited range, its advocates thought it a good candidate for listing as an endangered species, a status that would bring into force the habitat protection mandated by the Endangered Species Act of 1973. In a recognition of the political power wielded by these modest creatures, the Rocky Mountain News in 1985 ran the headline: “The Pawnee Montana Skipper: Is Its Future Worth a Dam?”¶¶¶¶ But, as in most other controversies involving a particularly noted and discussed species, this butterfly stood for a vast biological community that would be affected by the dam, including blue grama grass, musk thistle, and other indigenous plants for which the Pawnee montane skipper had a soft spot. The circumstances of creatures far from the site of the dam also had to be taken into account: sandhill cranes and piping plovers that relied on adequate flows downstream on the Platte, and the humpback chub and other endangered fish in the Colorado River that swam in increasingly shallow waters with each diversion from the Western Slope.50

¶¶¶¶ For a while, the Pawnee montane skipper was so new that no one seemed quite sure what its proper name was, and the Montana spelling was not uncommon in newspaper reports.

Just as in the Foothills controversy, the issuing of a Dredge and Fill Permit under section 404 of the Clean Water Act became the fulcrum of the conflict. Once again, the Army Corps of Engineers was the key agency in this permitting process. Following on the Foothills Agreement’s requirement of a system-wide, not just site-specific, environmental impact statement (EIS), the corps had begun work on such a study in 1981. By 1984, the Denver Water Board was getting impatient with the long, system-wide review process and notified the corps of its intent to file for the necessary permits to go ahead with Two Forks, a move that would force the corps to begin a site-specific EIS. After a round of negotiations, the corps agreed to prepare a joint EIS that would include system-wide and site-specific studies if Denver would delay submitting the permit applications and contribute funds to offset the additional costs of the expanded study. This agreement held Denver at bay until the spring of 1986, when the Water Board went ahead and filed an application to build Two Forks, several months before the corps was prepared to release its study.51

When the corps finally submitted its draft of the EIS in December 1986, it served notice that it intended to support Denver’s application for Two Forks by issuing the 404 Permit for the dam. In April 1987, EPA officials volleyed back, declaring the draft EIS to be riddled with environmental and technical shortcomings. After more jostling between and among federal agencies, the Denver Water Board and its suburban collaborators, and environmental groups, the corps issued its final EIS for review in March 1988. The recommendation had not changed; the corps believed that the project’s environmental impacts could be satisfactorily mitigated and that Two Forks should be built.

By the time this final EIS was submitted for public review, the study’s size, cost, and production had taken on epic proportions, weighing upon the earth as a portly twelve volumes. The technical documentation alone stacked more than six feet high. A Denver Water Board spokesperson explained how the document acquired such bulk: “We did one study and that study called for studying something else and that called for another study until it became just a monster.” Participating in this data scavenger hunt were “helicopter pilots, tree counters, butterfly catchers, lawyers, accountants, public relations people, newspaper clipping services, biologists, geologists, botanists, engineers, economists, and even dam builders.” The price tag for the study totaled $43 million, a cost that, by the terms of the Metropolitan Water Development Agreement, was split 80/20 between the coalition of Metropolitan Water Providers and the Denver Water Board. The study examined the organisms of the Platte Canyon and weighed the relative merits of dam types. It evaluated wetlands disturbance and erosion acceleration, channel stability below the dam, vegetation encroachment, overbank flooding, sediment transport, recreational opportunities, and the impact of the dam and reservoir on the local economy. Described by Ellison as the “largest and most costly environmental-impact statement ever,” the corps’ study of Two Forks proved to be the behemoth of a new, and consequential, genre of nature writing.52

For more than a century, the narrow canyon where the North Fork of the South Platte River converges with the main stream has been thought of as both a spectacular setting and an ideal dam site.

The National Environmental Policy Act had created a giant, nationwide enterprise in the production of EISs, creating a robust new market for the work of specialists, experts, and consultants. If it had itself been subject to EIS, the flood of paperwork generated by these reports would surely have been appraised as the equivalent, in wasting paper, of a thousand ticker-tape parades.

Denver Water’s leaders still had reason to think that the lesson of the Blue River Decrees and the Foothills Agreement—the vindication of persistence exercised through a season of great vexation—still applied. Despite the burdensome process of satisfying federal permitting requirements, as late as 1989 the campaign for the Two Forks Dam did not seem lost. On the contrary, in January, the Army Corps of Engineers announced that it was going to issue the section 404 Dredge and Fill Permit, with a formal motion of intent registered on March 15, 1989. The administrator of the EPA’s regional office in Denver, James Scherer, tilted toward recommending approval of the 404 Permit, even though some of the local EPA staff members who had worked most directly on the project disagreed with him.53

By a widely held stereotype, bureaucracies are such homogenizing, conformity-enforcing forms of social organization that they leave no room for individuals to affect the course of the lumbering machinery of an agency. As this split between the EPA local staff and their ostensible boss begins to indicate, the histories of the Foothills Treatment Plant and Two Forks Dam offer a compelling challenge to that stereotype. The qualities and convictions of the individuals holding office in the EPA constitute very big factors in both stories. In the 1970s, regional administrator Alan Merson was a thorn in the side for the Denver Water Board. In the 1980s, regional administrator James Scherer was quite the opposite, constituting a burr under the saddle for the environmentalists. But most consequential of all was the distinctive character of Scherer’s boss, the national EPA administrator William Reilly, appointed to office on February 8, 1989, by President George H. W. Bush, just as the Two Forks controversy reached its moments of decision.

If the EPA had been unsure of the practicable extent of its authority during the Foothills controversy, by now the agency was confident and assured in exercising its power. When Merson stated his objections to the Foothills Treatment Plant in 1978, the EPA had never actually killed a project with a 404(c) Veto. But by the time Reilly took the helm in 1989, the agency was on a streak, having vetoed eight projects in the previous eight years.54

On March 24, 1989, Reilly announced that the EPA would review the corps’ decision to issue the 404 Permit, invoking a provision in section 404(c) of the Clean Water Act that granted the EPA veto power over projects that would result in an “unacceptable adverse effect on municipal water supplies, shell-fish beds, fishery areas, wildlife, or recreational areas.” When Scherer expressed qualms about backtracking on his support for the project, Reilly stepped around the authority of his Denver-based regional administrator and appointed the regional administrator in Atlanta, Lee DeHihns, to oversee the review process. If it seemed like he was stacking the deck against Two Forks, he was. Reilly’s prepared statement about the review made the likely outcome unambiguous: “The proposed project contemplates the destruction of an outstanding natural resource,” he explained, declaring that “I do not believe this project meets the guidelines . . . of the Clean Water Act.”55

DeHihns considered the issue (and, one might suppose, the views of his boss) throughout the summer before publicly announcing his findings on August 29, 1989. Citing the “extremely high fish, wildlife, and recreational value” of the area proposed for inundation, he reviewed a litany of threats Two Forks posed to these assets. His considerations included the South Platte’s gold medal trout fishery, threatened and endangered fish in the Colorado River Basin, local aeries of bald eagles and peregrine falcons, elk and mule deer herds in the area, recreational whitewater on the Western Slope, water quality in the Blue and Williams Fork Rivers, numerous species that relied on the river habitat in Nebraska, and the vulnerable Pawnee montane skipper. Of the rare butterfly, DeHihns noted that it could well be “lost before the mitigation methods can be proven to work.” Weighing against these damages was the Denver metropolitan area’s need for water, but DeHihns accepted the arguments put forward by the Colorado Environmental Caucus and others that practicable (even superior) alternatives to Two Forks existed for providing this water. His considerations led to one clear conclusion: “the adverse effects of Two Forks dam and reservoir would be unacceptable. Moreover, it appears these impacts are partly or entirely unnecessary and avoidable.”56

Denver and its allies vigorously protested and disputed DeHihns’s report and EPA’s entire 404(c) review process. Colorado’s congressional delegation even asked the Government Accounting Office to investigate EPA’s handling of the review. But nothing shook DeHihns and Reilly from their initial conclusion. After several rounds of public comment on DeHihns’s findings, administrator Reilly accepted the recommendation and officially delivered his veto of the project on November 23, 1990, making it the eleventh project vetoed by the agency under the authority granted to it in section 404(c) of the Clean Water Act.57

In an extensive interview after he left office, Reilly said that his veto of Two Forks was “one of the most controversial decisions I had made.” Controversy did not lead Reilly to regret or to ambivalence over his action. When he was asked to name his most significant accomplishments, he responded, “first, the elevation of ecology and the signaling of the end to expensive and wasteful water development in the West, which I think is the message of the veto of Two Forks Dam.”58

Reilly’s veto of Two Forks, along with the backing he received from President Bush, offers another direct challenge to the conventional wisdom that Republicans are inherently supporters of development and opponents of environmental preservation. His earlier career had many elements that gave him particular qualifications for appraising the Two Forks proposal. As a young attorney, he worked for the CEQ, where he helped draft the regulations that would “implement the National Environmental Policy Act and the Environmental Impact Statement procedures.” He chaired a task force for the CEQ that in 1973 produced a report entitled The Use of Land: A Citizen’s Policy Guide to Urban Growth, a text that had unmistakable relevance for Denver. Reilly became president of the Conservation Foundation, which then merged with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). He was president of the WWF when George H. W. Bush, who had punctuated his 1988 campaign with repeated declarations of his hope to be “the environmental president,” asked him to become EPA administrator. Reilly recalled that President Bush “expressed his own philosophy” by saying, “I’m not a rape-and-ruin developer and I’m not for locking everything up, either.” When the president told him “that he believed in balance,” the new EPA administrator was in hearty agreement: “That’s really my philosophy. It’s one of integration and reconciliation of priorities.” Reilly had not been a career politician, and he characterized himself as an outsider in the Bush administration. He did not come to office with a preexisting constituency. “My constituency,” he said, “had to be the country.”59

Reilly was a man of independence and self-confidence, but he did not, in making this move, have to defy the president who had appointed him. Nebraska’s Republican governor Kay Orr had conveyed reports on the swing of public opinion against Two Forks to the president (since the Platte flows through Nebraska, upstream storage would affect the state). And, as a frequent vacationer in Colorado, former president Gerald Ford was well-informed on the controversy and wrote President Bush personally to urge him to review the project critically. One leader of the opposition to Two Forks offered a significant tribute to President Bush: “What this means from Bush is ‘I really meant it when I said I was an environmentalist.’” A later commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation made the point even more emphatically: “It was Bush that killed the Two Forks Dam.”60