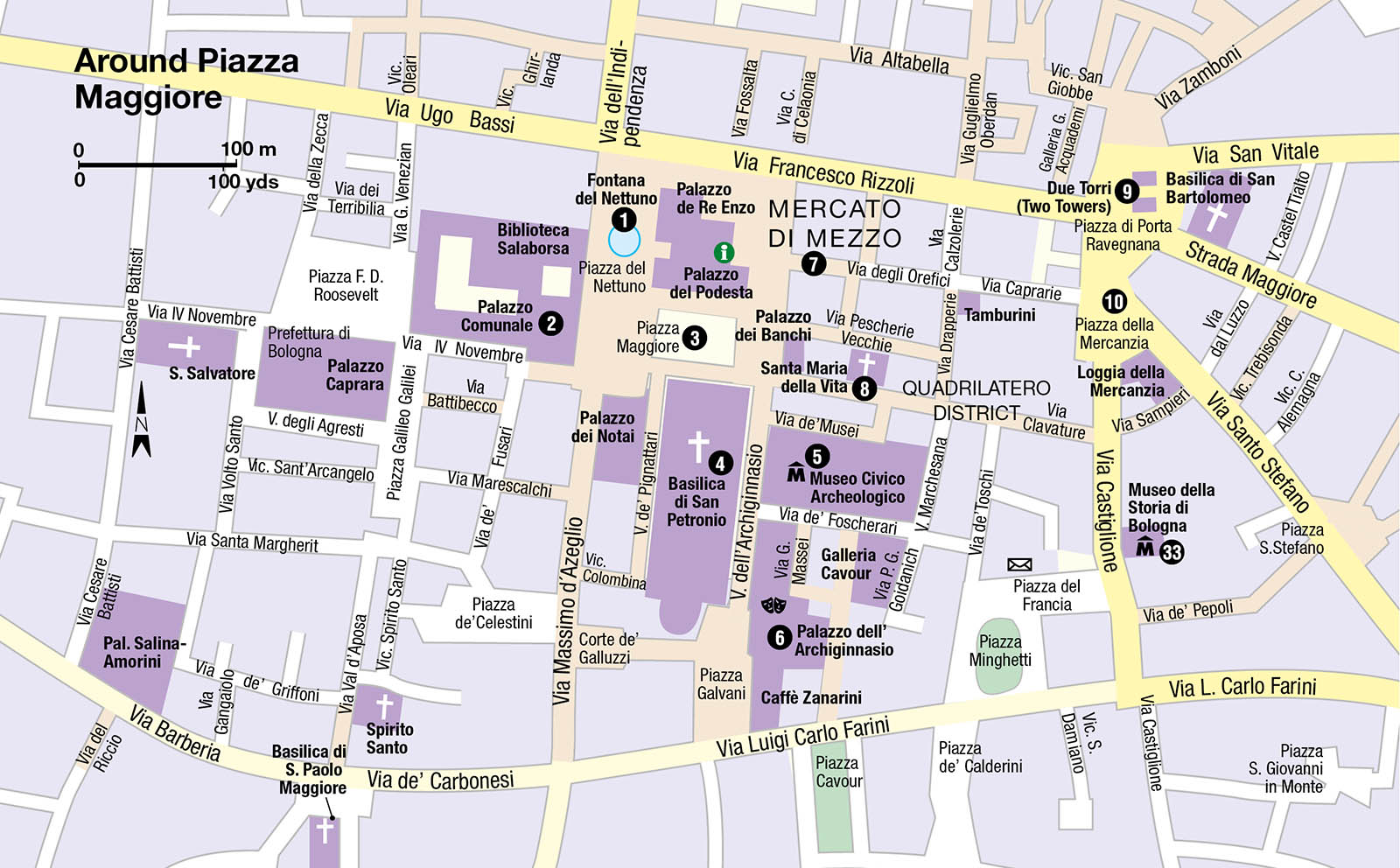

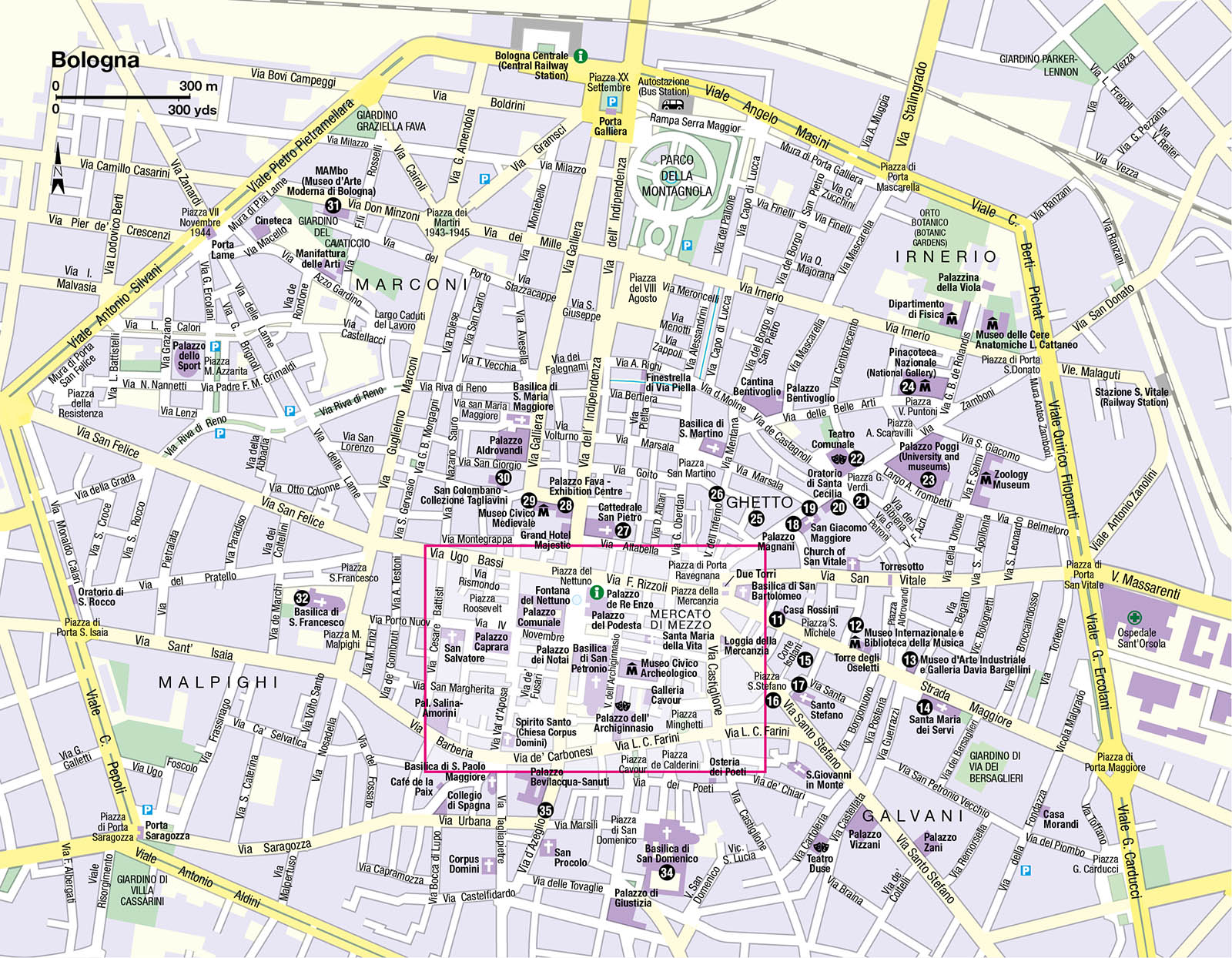

Bologna is the perfect place to explore on foot. Almost all of the cultural attractions are packed into the historic centre, a large part of which is a Limited Traffic Zone, where traffic is restricted from 7am to 8pm. Furthermore the city is flat and the pavements are protected by arcades. From Piazza Maggiore and from the hub around the famous two towers, streets fan out towards the city gates and the viali, the circle of avenues which follows the ancient walls. Via dell’Indipendenza links the rail and bus stations to Piazza Maggiore, and at its southern end forms a T with Via Ugo Bassi running west and Via Rizzo running east. These three main arteries, which are Bologna’s high streets, are completely vehicle-free at weekends.

Fontana del Nettuno is a popular meeting point

Getty Images

Piazza Maggiore and Around

Piazza Maggiore and its antechamber, Piazza del Nettuno, form the symbolic heart of the city, showcasing the political and religious institutions that define independent-minded Bologna. Overlooked by brick-built palazzi and the vast mass of San Petronio the sweeping Piazza Maggiore was (and to a certain extent still is) the stage setting where Bolognesi gathered for speeches, ceremonies, meetings and protests. The square is also a showcase for daily life, from Prada-clad beauties to protesting students, pot-bellied sausage-makers to perennially flirtatious pensioners. Just off the piazza the labyrinthine food market provides culinary diversion and the porticoes shelter some of the city’s most exclusive shops.

Piazza del Nettuno

The focus of the piazza is Fontana del Nettuno 1 [map], the celebrated bronze fountain to Neptune sculpted by Giambologna in 1556. An Italian in all but birth (he was born Jean Boulogne in Flanders) the Mannerist sculptor spent most of his working life in Florence but it was the Fountain of Neptune in Bologna which made his name. The sculpture depicts a monumental, muscle-bound Neptune (nicknamed ‘Il Gigante’) with four putti, representing the winds, and four voluptuous sirens who sit astride dolphins, spouting water from their nipples. Given Bologna’s turbulent relationship with the papacy, the citizens delighted in the fact that the nude Neptune was considered a profane, pagan symbol by the papal authorities. The statue caused a furore when first unveiled and a Counter-Reformation edict decreed that Neptune should be robed. But the priapic sea god is now free to frolic. (Locals take great delight in pointing out the best vantage point for viewing the god’s impressive manhood).

The Neptune Maserati link

Motoring enthusiasts may recognise Neptune’s trident in the Fontana del Nettuno. It was adopted by the Modena-based Maserati car company as their logo.

Palazzo Re Enzo and Palazzo del Podestà

Facing the fountain, on the east side of the square, stands Palazzo Re Enzo (access only during exhibitions), named after the son of Emperor Frederick II, Enzo ‘King of Sardinia’, who was defeated at the Guelphs versus Ghibellines Battle of Fossalta in 1249 and was imprisoned here for 23 years until his death in 1272. Adjoining the palace and facing Piazza Maggiore is the elegant Palazzo del Podestà (access only during exhibitions), built as the political seat of power in the 13th century. It is graced by a Renaissance porticoed facade on the Piazza Maggiore side and distinguished by its 13th-century brick tower, the Torre dell’Arengo, originally built to summon citizens in case of emergency. The vault below, the Voltone del Podesta, was once occupied by terracotta statues of the town’s patron saints. The attraction today is the echo in the ‘whispering gallery’ – face one of the four corners of the arcade and your voice will be transmitted to the opposite corner.

The porticoed Palazzo del Podestà

Shutterstock

The wall on the west side of Piazza del Nettuno features photos of hundreds of partisans who fought for the Resistance in World War II. Of the 14,425 local partisans, including over 2,000 women, 2,059 died. Italy was liberated from Nazi domination on 21st April 1945 by which time Bologna had been devastated by aerial bombardments. A further memorial honours the victims of the bomb explosion at Bologna’s main railway station in 1980 which left 85 dead and 200 wounded.

Palazzo d’Accursio

The vast and imposing building on the west side of Piazza Maggiore is the Palazzo d’Accursio, also known as the Palazzo Comunale 2 [map] (www.museibologna.it/arteantica; Tue−Sun 9am−6.30pm, some ceremonial halls open Tue−Sun 10am−1pm if not being used for council meetings; charge only for the Collezioni Comunali d’Arte, the Municipal Art Collection). The palace dates back to the 13th century and was originally the residence of a well-known medieval lawyer, Accursius. It was later bought by the city and remodelled as an affirmation of papal authority. In 1530, two days before he was crowned Emperor in San Petronio, Charles V was crowned King of Italy in the chapel of the Palazzo d’Accursio, receiving the Iron Cross of Lombardy. A suspended passage was built especially for the occasion, linking the palace to San Petronio across Piazza Maggiore.

Palazzo Comunale, the medieval town hall remodelled in the Renaissance

Getty Images

The huge bronze statue (1580) above the portal of the palace depicts Pope Gregory XIII, the Bolognese pope who reformed the old Roman calendar, replacing it with his own Gregorian one, still in use today. Above and to the left of the doorway is a beautiful terracotta statue of the Virgin and Child (1478) by the Italian sculptor Niccolò dell’Arca. Cross the courtyard and climb the magnificent corded staircases, where horses once thundered past, to the frescoed interiors on the first and second floors. Restyled by papal legates in the 16th century, the ceremonial halls are elaborately frescoed and have fine views over Piazza Maggiore. The Sala Rossa, or Red Room, with its huge chandeliers, is a favourite venue for civil ceremonies. The Museo Morandi which opened here in 1993 was moved to MAMbo (for more information, click here) in 2012 while this part of the palace was restored. The museum will return here after the work is complete. The many rooms of the Collezioni Comunali d’Art at the top of the palace display Emilian works of art from the 13th to 19th centuries, worth visiting for a sense of the decor, furnishings and artistic taste under papal rule, rather than for great art.

Salaborsa

Part of the monumental Palazzo Comunale complex, the Biblioteca Salaborsa (Mon 2.30−8pm, Tue−Fri 10am−8pm, Sat 10am−7pm; free) was built within the shell of the former Stock Exchange (Borsa). The building is now a spacious multimedia library and cultural space, designed in Art Nouveau style. A glass floor in the Covered Square reveals excavations of the medieval and Roman settlements including part of the forum and Roman pavement, and these can be accessed from the lower basement level (Mon 3−6.30pm, Tue−Sat 10am−1.30pm and 3−6.30pm; free).

Before its current role, this sizeable section of the Palazzo Comunale served diverse purposes. In 1568 the Bolognese naturalist, Ulisse Aldrovandi, founded Bologna’s Botanic Garden in the courtyard here for the academic study of medicinal plants. This was one of the first botanic gardens in Europe (Bologna’s botanic garden today is in the university quarter). The courtyard later became a training ground for the military, then in the 20th century served variously as bank offices, a puppet theatre and a basketball ground before becoming the Stock Exchange.

Piazza Maggiore

A sunny day is a summons to sit at café tables in the Piazza Maggiore 3 [map] or on the steps under the arcades and soak up the atmosphere. Dominating the great central square is the vast but incomplete Basilica of San Petronio, favourite church of the Bolognesi. The slightly raised platform in the middle of the piazza is familiarly called the crescentone after the name of the local flat bread, crescente, which it resembles in shape.

Bologna Welcome Card

The excellent tourist office on Piazza Maggiore can supply you with a Bologna Welcome Card. At €25 for the Bologna Welcome Card Easy and €40 for the Bologna Welcome Card Plus, they are good value giving you free admission to many city museums and attractions, plus discounts for shops, restaurants and events. Also available at www.bolognawelcome.com.

Basilica di San Petronio

Dedicated to Petronius, the city’s patron saint, the 14th-century Basilica di San Petronio 4 [map] (www.basilicadisanpetronio.it; Mon−Fri 7.45am−1.30pm, 2.30−6pm, Sat−Sun 7.45am−6.30pm; church: free, terrace: charge) is the city’s principal church. As one of the most monumental Gothic basilicas in Italy, the church would have been larger than St Peter’s in Rome had not Pope Pius IV put a stop to construction by using the funds for the creation of a new university, the Palazzo Archiginnasio. As a consequence the facade was never completed, hence only the partial cladding in pink Verona marble and the cut-off transept which you can see down the alley to the right of the basilica. Even so, San Petronio is still monumental and remains the city’s best-loved church, representing a manifestation of civic will rather than religious power. Built over Roman foundations the vaulted church reveals columns recycled from the Augustan era, which meld perfectly with medieval additions.

The highly expressive reliefs on the Porta Magna, the central portal, were the last great work of Sienese sculptor Jacopo della Quercia, occupying the last 13 years of his life (1425−38). The architrave displays scenes from the New Testament, and on the two pilasters on either side of the door, dramatic reliefs with subjects taken from the Old Testament. Michelangelo, who visited Bologna in 1494, admired these reliefs and used several of the motifs (such as The Creation of Adam) for the Sistine Ceiling. The lunette features the Madonna and Child between St Petronius and St Ambrose.

San Petronio’s half-completed facade

Shutterstock

The immense but simple interior of the basilica has witnessed historical events, not least of which was the crowning of Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor in 1530 (for more information, click here). Set in the floor on the left is a 17th-century sundial, measuring almost 60m (197ft) and said to be the world’s biggest church sundial. It was of particular interest to travellers on the Grand Tour and today it still attracts plenty of interest, especially at noon on a sunny day when rays touch the line of the sundial. The second chapel on the left is dedicated to San Petronio and contains the relics of the saint. The Bolognini Chapel (4th on the left) remains virtually intact, and has striking early 15th-century frescoes by Giovanni da Modena, depicting the Journey of the Magi, the Life of St Petronius, Paradise and a harrowing scene of the Last Judgement. There are 20 more chapels, an organ to the right of the altar, dating from 1470 and still functioning (the one opposite still works too but is relatively modern at 1596), and a museum with projects for the completion of the facade which were never carried through.

From the recently revamped panoramic terrace of the basilica (access from Piazza Galvani by lift and a few steps; Mon−Thu 11am−1pm, 3−6pm, Fri−Sun 10am−1pm, 2.30−6pm) there are splendid views of the cityscape and the Apennine hills to the south.

Madonna and Child above the altar

Shutterstock

City of Porticoes

A distinctive feature of the city are the portici, or porticoes, extending almost 40km (25 miles). These graceful, tranquil arcades were originally built of wood outside shopkeepers’ houses as extra space for trade. The original portico had to be a minimum of 7 ‘Bolognese feet’ high (2.66m) to enable those on horseback to pass through. From 1568, due mainly to fire hazards, porticoes had to be made of brick or stone. A few of the old wooden ones survive and one of the best preserved examples is the lofty portico of Casa Isolani in Strada Maggiore. The Portico San Luca, running for nearly 3.5km (2 miles) up to the hilltop Sanctuary of San Luca, is the longest portico in the world. Over the centuries the porticoes have been much admired by travellers both for their architectural interest and their protection against the elements. In a city renowned for rain and snow in winter, and searing heat in mid-summer, they couldn’t be more convenient.

Museo Civico Archeologico

From Piazza Maggiore the Via Archiginnasio takes you under the porticoes past the city’s most elegant shops, including the loveliest arcades, known as the Pavaglione. The Museo Civico Archeologico 5 [map] (www.museibologna.it/archeologico; Mon and Wed−Fri 9am−6pm, Sat−Sun 10am−6.30pm; opening times may be extended during temporary exhibitions) is housed in the former hospital of Santa Maria della Morte (of Death), which was dedicated to the terminally ill. The lovely courtyard is framed by Roman statuary and leads to Giambologna’s statue of Neptune which is displayed at the top of the main staircase. Bologna’s early history is traced through Celtic tools, Etruscan urns, Attic vases and Classical Greek terracottas, proof that the Bolognese talent for trading dates back to its earliest history. The sheer number of exhibits – around 200,000 − in old-fashioned dimly lit galleries can be overwhelming but the museum has one of the best Etruscan collections in Italy. Two large galleries are devoted to the Etruscan civilisation in Bologna (9th−4th centuries BC), featuring terracotta and bronze ossuaries, funerary stelae with depictions of fantastic animals and exquisite terracotta askos (small vessels for pouring liquids). There are also good displays of Roman antiquities and (easy to miss) an impressive Egyptian collection in the basement.

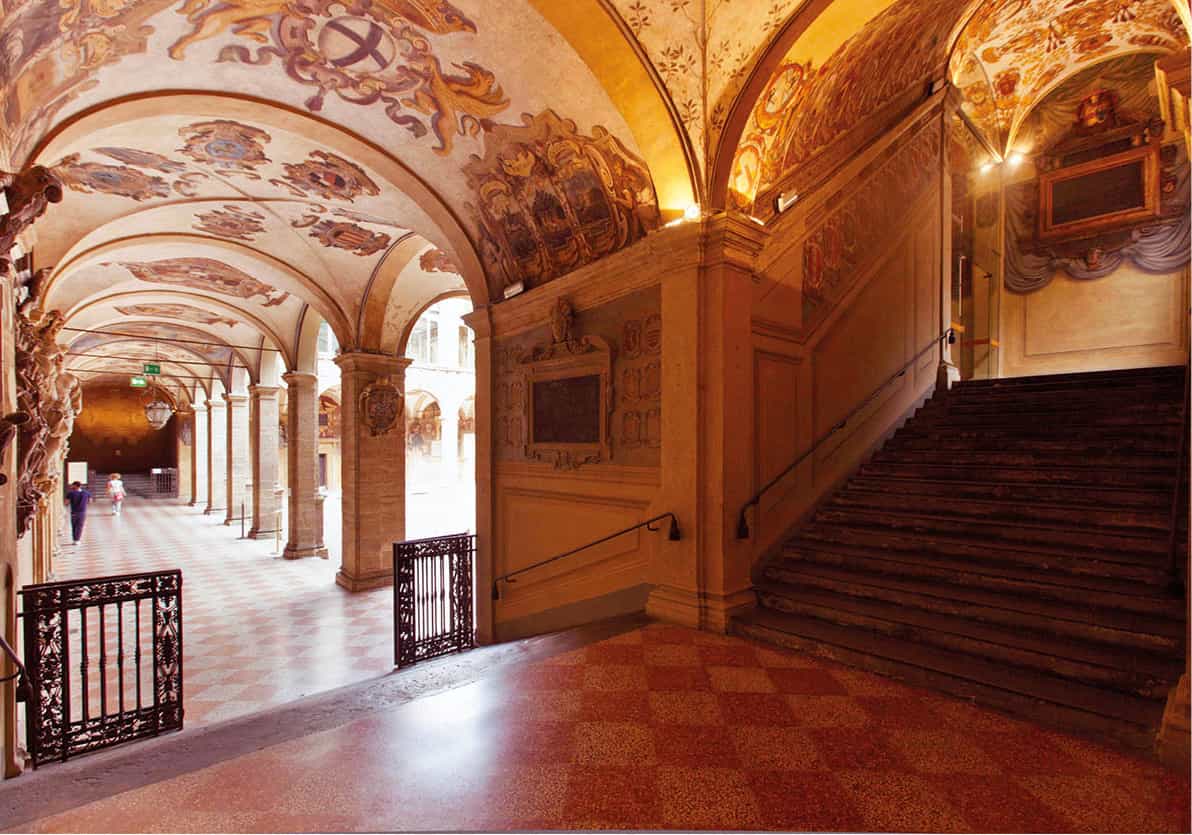

Just beyond the Archaeological Museum is the cultural set-piece of the frescoed Palazzo dell’Archiginnasio 6 [map], built in 1562−3 as the first permanent seat of Europe’s most ancient university (www.archiginnasio.it; Palace Courtyard and open gallery: Mon−Fri 10am−6pm, Sat 10am−7pm, Sun 10am−2pm, free; Anatomical Theatre and Stabat Mater Hall: Mon−Fri 10am−6pm, Sat 10am−7pm, Sun and hols 10am−2pm, if not occupied by events). Before the construction of the Archiginnasio the schools of law and medicine had been scattered around various venues of the city. This remained the seat of the university until 1803 when it moved to its current location in Via Zamboni. Today the palace houses the precious collection of 800,000 works of the Biblioteca Comunale (City Library), the richly decorated Sala dello Stabat Mater, a former lecture hall where Rossini’s first Italian performance of Stabat Mater was held in 1842 under the direction of Donizetti, and the fascinating Teatro Anatomico (Anatomy Theatre).

The fine courtyard, with its double loggia, and the staircase and halls are all decorated by memorials commemorating masters of the ancient university together with around 6,000 student coats of arms. The courtyard was frequently the scene of university ceremonies, one of the most intriguing being the Preparation of the Teriaca (Theriac), a drug for animal bites and later the all-cure medicine, formulated by the Greeks in 1st century AD and concocted from fermented herbs, poisons, animal flesh, honey and numerous other ingredients.

Some of the first human dissections in Europe were performed in the Teatro Anatomico, shaped like an amphitheatre and adorned with wooden statues of famous university anatomists of the university and celebrated doctors. There is nothing remotely macabre about the tiered seats and professors’ chair − apart from a canopy supported by depictions of a couple of skinned cadavers, gli spellati. The Church forbade regular sessions of dissections but when they did take place they were popular events, open to the public. As photos at the entrance illustrate, this wing of the building was devastated during the bombardment of 1944, but was reconstructed immediately after the war, using the original wooden sculptures that were salvaged from the rubble.

Legendary Tamburini deli

Alamy

The Via dell’Archiginnasio leads into Piazza Galvani, named after the 18th-century Bolognese scientist Luigi Galvani, pioneer of bioelectromagnetics. Through his experiments on frogs he established that bioelectric forces exist within animal tissue. The statue in the square shows Galvani gazing at a frog on a stone slab. For a break from sightseeing head to Zanarini on the corner of the Piazza, a great spot for coffee and cakes.

Quadrilatero

The maze of alleys tucked away off Piazza Maggiore is known as the Quadrilatero. It is an ancient grid of food shops where the mood is as boisterous as it was in its medieval heyday. The ancient guilds of the city, such as goldsmiths, blacksmiths, butchers, fishmongers and furriers had their headquarters here and many of the street names today recall their trades. The market is the place for a true taste of Emilia, with open-air stalls, specialised food shops and a covered market, Mercato di Mezzo 7 [map], now transformed into a stylish food hall selling enticing regional produce and a wide range of freshly made tapas-style snacks to take away or eat in, very casually, at communal tables. From here the market spills out onto Via Drapperie, Via Clavature and Via degli Orefici. Gaze and graze is the mantra of most visitors. On offer are juicy peaches and cherries, sculpted pastries, navel-shaped handmade pasta, slivers of delicious pink Parma ham, succulent Bolognese Mortadella, still-wriggling seafood and wedges of superior ‘black rind’ parmesan.

By day, few people can resist lunch at Tamburini (Via Drapperie/Via Caprarie 1), the legendary gourmet deli with a self service, followed perhaps by a delicious pastry at Atti (Via Drapperie 6); or a picnic of charcuterie from Salumeria Simoni (Via Drapperie 5/2A), where whole hams hang from the ceiling and wheels of cheeses and thick rolls of Mortadella are crammed into the windows. In the evening the Quadrilatero becomes a chic spot for an aperitivo in an outdoor café.

Where Time Stands Still

Only the word ‘Vino’ above the doorway hints that you might have arrived at an inn. The inconspicuous Osteria del Sole, just off Via Pescheria at Vicolo Ranocchi 1D (www.osteriadelsole.it) is Bologna’s oldest inn, dating from 1465. It’s an atmospheric, rough-and-ready spot, with old framed photos on the walls, cheap wine served by the glass and long tables for customers to bring their own food − which they have done for centuries. Pick up a picnic from the market stalls or from neighbouring delis, order your glass of Sangiovese or Pignoletto and sit with cheerful old boys playing cards, students from the university or the occasional tourist who has managed to locate this elusive inn.

Santa Maria della Vita

After the bustle of the surrounding market the church of Santa Maria della Vita 8 [map] (Via Clavature 8; www.genusbononiae.it; Tue−Sun 10am−7pm) is a haven of peace. Although boldly frescoed the restored Baroque interior is overshadowed by the Lamentation over the Dead Christ (1463) by Niccolò dell’Arca, a remarkable composition in terracotta portraying life-size grieving mourners at the death of Christ. The church was part of a religious hospital complex and it is thought that Niccolò dell’Arca may well have studied the faces of the sick and suffering to have achieved such stunning expressions of grief. The figure of Nicodemus is traditionally described as a self-portrait. In the oratory, where temporary exhibitions are held, there is another poignant lament in terracotta, the Death of the Virgin, by Alfonso Lombardi.

Lamentation over the Dead Christ

Getty Images

East of Piazza Maggiore

With its long rows of noble palazzi and secret courtyards, the east side of the medieval city has always been the most fashionable quarter of the city. The Strada Maggiore follows the route of the Roman Via Emilia which linked with the Via Flaminia – the route to Rome. The porticoed street is lined by a succession of senatorial palazzi which once belonged to ruling families. To the north, Via San Vitale was formerly called Via Salaria, for it was along here that salt was transported into the city from the Cervia salt flats south of Ravenna. Via Santo Stefano, the ancient road to Tuscany, is flanked by yet more fine mansions and leads to, and beyond, the beguiling complex of Santo Stefano.

The view over the sea of red rooftops from the Torre degli Asinelli

Shutterstock

Due Torri

Dominating Piazza di Porta Ravegnana, site of the main gate of the Roman walls, are the Due Torri 9 [map], the Two Towers. The Torre degli Asinelli (www.duetorribologna.com; daily Mar−Oct 9.30am−7.30pm, Nov−Feb 9.30am−5.45pm) and the Torre Garisenda (no access) are the most potent symbols of the medieval era, when Bologna bristled with around 120 towers. Both date back to the 12th century, and were probably built as watchtowers as well as status symbols. Legend has it that the two richest families in Bologna, the Asinelli and the Garisenda, competed to build the tallest and most beautiful tower in the city.

A sense of history and a bird’s eye view over the terracotta rooftops should tempt you to the top of Torre degli Asinelli (over 97m/318ft). It is admittedly a steep climb, with a narrow spiral staircase of 498 steps, but worth the effort. From the top you can locate some of the other 20-odd surviving medieval towers and, weather permitting, the foothills of the Alps beyond Verona. Like most of Bologna’s towers, the Due Torri are both tilting: Garisenda 3.33m (11ft) to the northeast, Asinelli 2.23m (7.3ft) to the west. Garisenda originally rose to 60m (197ft) but it was built on weak foundations, and for safety reasons 12m (39ft) was lopped off in the mid-14th century. From certain angles, however, the two towers appear to be the same height. Dante, who was briefly in Bologna during his exile from Florence, and saw the acutely tilting tower (before it was shortened), included it in The Inferno, where he compares it to the bending Antaeus, giant son of Poseidon, frozen in ice at the bottom of hell. His quote is engraved on a plaque at the base of the tower.

Below the towers, but in no way inconspicuous, is the 17th-century church of San Bartolomeo, with a Renaissance portico. Look for the Annunciation by Francesco Albani in the fourth chapel of the south aisle, and the small Madonna with Child by Guido Reni in the north transept. On the north side of the square the intrusion of a starkly modern office building invariably caused a furore when constructed in the 1950s.

Tilting towers

In 1786 the German writer Goethe, in unusually flippant mood, got the measure of the Bolognese nobility: “Building a tower became both a hobby and a point of honour. In time, perpendicular towers became commonplace, so everyone wanted a leaning one.”

Piazza della Mercanzia

Heart of the commercial district since medieval times, Piazza della Mercanzia ) [map] is dominated by the crenellated Palazzo della Mercanzia, formerly the merchants’ exchange and customs house, now seat of Bologna’s Chamber of Commerce. The Gothic facade is adorned by statues representing the city’s patron saints who smile benignly on an economy once based on gold, textiles, silk and hemp, but now in thrall to local success stories such as silky La Perla lingerie, hemp-free Bruno Magli shoes and Mandarina Duck bags. The palace safeguards the original recipes of local specialities, such as Bolognese tagliatelle al ragù (with the real Bolognese sauce). Pappagallo (for more information, click here), a charming old-world institution in a beautiful 13th-century building on the piazza, is a good place to try it.

Palazzo della Mercanzia

Shutterstock

Strada Maggiore

Running southeast from Piazza Mercanzia is Strada Maggiore or Main Street, with an almost uninterrupted succession of aristocratic residences. On the left-hand side, at No 26, is the Casa Rossini ! [map], the composer’s home from 1829 and 1848. Just beyond it on the right is the lofty and quaintly porticoed Casa Isolani, one of the city’s few surviving 13th-century houses. Beyond it the Caffè Commercianti (No 23c) is traditionally favoured by academic types including the late polymath and best-selling author, Umberto Eco. Modelled on a Parisian café, it has Art Deco and Art Nouveau touches, and makes a chic coffee or cocktail stop.

Museo Internazionale e Biblioteca della Musica

A mere baton’s throw from Rossini’s home, the Palazzo Sanguinetti at No 34 Strada Maggiore is home to the delightful Museo Internazionale e Biblioteca della Musica @ [map] (International Museum and Library of Music; www.museibologna.it/musica; Tue−Sun 10am−6.30pm). Rossini and his second wife, Olimpia Pelissier, were hosted here by their tenor friend, Domenico Donzelli. The museum is a recognition of Bologna’s musical status: nine rooms trace six centuries of European music through 80 rare and antique musical instruments along with scores, historical documents and portraits. Even those who are not fans of classical music will be entranced by the trompe-l’œil courtyard and the frescoed interiors, offering a rare chance to see how the Bolognese nobility lived. The salon-like atmosphere, reflected in the mythological friezes and whimsical pastoral scenes, makes this the most enchanting city palace. The music library, with over 100,000 volumes opened here in 2014, after its transfer from Piazza Rossini.

Mozart and Martini

In Room 3 of the Museum of Music you can find memorabilia of the young Mozart including two versions of his entrance exam to the Accademia Filarmonica di Bologna. His written test did not comply with the strict academic rules, so Father Giambattista Martini, who had taught Mozart and recognised his genius, secretly handed him the correct version. The museum has two versions of his test below his portrait, one of which includes several mistakes. Mozart came to Bologna twice in 1770 when he was 14. On the first occasion he performed a private concert for Count Pallavicini in his palace in Via San Felice and stayed at the Albergo del Pellegrino, which no longer exists.

Museo Civico d’Arte Industriale e Galleria Davia Bargellini

Beside the Palazzo Sanguinetti looms the Torre degli Oseletti, a medieval tower which was originally 70m (230 ft) tall. At the junction of Strada Maggiore and Piazza Aldrovandi, you are unlikely to miss the ‘Palace of the Giants’, Palazzo Davia Bargellini, whose entrance is flanked by two Baroque telamones. The palace is home to the Museo Civico d’Arte Industriale e Galleria Davia Bargellini £ [map] (www.museibologna.it/arteantica; Tue−Fri 9am−1pm, Sat−Sun 10am−6.30pm; free), a collection of applied and decorative arts, and notably Bolognese paintings, many of which belonged the Bargellini family who started collecting in 1500. Works include Vitale da Bologna’s famous Madonna dei Denti (Madonna of the Teeth), a Pietà (1368) by his contemporary Simone dei Crocifissi, and the Giocatori di Dadi (The Dice Players) by Giuseppe Maria Crespi (1740), who specialised in genre scenes with vivid chiaroscuro effects. The last room holds an 18th-century Bolognese puppet theatre.

Santa Maria dei Servi

Across the road is the lovely Gothic Santa Maria dei Servi $ [map] (Mon 7.30am−12.30pm, Tue−Sun 7.30am−12.30pm, 4−7pm; free), graced by an elegant portico. Work on the church started in 1346 but it was almost two centuries before completion. The most interesting works of art lie behind the elaborate altar including (on the right side) fragment frescoes on the ceiling by Vitale da Bologna and, in a chapel on the left which you have to light up, an Enthroned Madonna (1280−90) traditionally attributed to the great Tuscan master Cimabue, but now thought to be from his workshop.

Gothic Santa Maria dei Servi

Getty Images

From Strada Maggiore the Corte Isolani % [map], entered under the portico of Casa Isolani, is a bijou warren that runs into Via Santo Stefano. Gentrification has turned this cluster of medieval palaces into chic art galleries, desirable apartments, wine bars and cafés. Via Santo Stefano is every bit as gracious as Strada Maggiore with late Gothic palaces once favoured by Bolognese silk merchants. Regular upward glances often reveal 12th-century tower-houses incorporated in late-medieval residences and embellished with Renaissance facades. Piazza Santo Stefano ^ [map] is a gentrified neighbourhood square (though more triangular than square), at its most convivial during an antiques market or gourmet food fair. This sought-after quarter numbers the once-radical politician, Romano Prodi, among its ranks − proof, if needed, that politically red Bologna now prefers pale pink.

The cobbled piazza forms the intimate backdrop to Santo Stefano & [map] (daily 9.15am−7.15pm, winter until 6pm; free), the city’s most hallowed spot. You will need plenty of time to appreciate and work out this ecclesiastical labyrinth, with its feast of ancient and medieval churches. Originally it was a complex of seven churches in one, as at Jerusalem, and it is known as Le Sette Chiese (‘the Seven Churches’) despite the fact that only four survive.

Santo Stefano church complex

Shutterstock

The complex dates back at least to the 5th century and may have been founded by Bishop Petronius as his cathedral on the site of a former pagan temple. His corpse was discovered here in 1141. The Lombards established their religious centre here, it then became a Benedictine sanctuary in the 10th century. Santo Stefano is still run by stern Benedictines who only soften when talking of the basilica’s enduring appeal. One white-clad brother confides: “Dante often came here to meditate in 1287 but we are not fussy − at Easter even the local prostitutes come here for confession”.

A harmonious ensemble is created by the interlocking churches and courtyards, including the Benedictine cloisters, graced by an elegant well head. Seen from the beautiful Piazza Santo Stefano the larger church on the right is the Chiesa del Crocifisso (Church of the Crucifix), the one in the middle the Church of San Sepolcro modelled on Jerusalem’s Holy Sepulchre, and on the left Santi Vitale e Agricola, the oldest church in Bologna. Enter through the Chiesa del Crocifisso, of Lombard origin but which has undergone the most transformation. The church ends with a central stairway that climbs to the Presbytery. Steps lead down to a graceful little crypt, built to house the relics of the early Bolognese martyrs Vitale and Agricola who died around 304 AD. Their remains are contained in a golden urn on the altar. A door on the left of the main church leads into the most famous of the churches: the Basilica of San Sepolcro, a small and unusual polygonal, surrounded by columns, some of which survive from an ancient pagan temple. The body of St Petronius was found in this church in the mid-12th century; his relics used to lie in an urn in the centre of the small chapel but were transferred in 2000 to join the saint’s head in the Basilica of San Petronio.

Bathed in mystical light the 11th-century Santi Vitale e Agricola is most compelling. Unadorned and built of bare brick it retains the most Romanesque Lombard character of all the churches in the city. It is dedicated to the first Bolognese martyrs, Vitale and Agricola, whose graves were discovered in 393 by the great bishop of Milan, St Ambrose. Adjoining it is the Cortile di Pilato (Pilate’s Courtyard) a fine brick-walled courtyard with a large marble basin erroneously believed to have been used by Pontius Pilate to wash his hands. Under the arcades are chapels and tombstones. Beyond the courtyard lies the mystery Martyrium, a transverse church also named the Holy Cross or Trinity Church. Little is known of its origin and history. As you walk along there are niches that light up, one with a sculpted scene of the Adoration of the Magi by the Bolognese artist Simone de’ Crocifissi. The courtyard leads into the peaceful Benedictine cloister, with two tiers of loggias. In the corner is a tiny museum of early Bolognese paintings and reliquaries, and a shop selling liqueurs and lotions made by Carmelite monks.

The University Quarter

The University of Bologna, founded in the 11th century and famous in its early days for reviving the study of Roman law, is the oldest university in Europe. Petrarch attended classes here, as did Erasmus, Copernicus, various popes and cardinals – and more recently Guglielmo Marconi, Enzo Ferrari and Giorgio Armani. It is ranked the number one university in Italy and today attracts over 85,000 students annually from around the world. The heart of the student area is the triangle between Via Zamboni and Via San Vitale, but the university quarter also spills out onto Via delle Belli Arti. It is one of the most diverse districts, studded with churches, palaces and museums as well as arty bookshops, eclectic cafés, shabby-chic student dives and graffiti-splashed porticos. The curious Palazzo Poggi, sumptuous seat of the University, is home to several of the university’s specialist museums and the Pinacoteca Nazionale boasts the richest art collection in the region.

A leisurely stroll down Via Zamboni reveals the faculties of modern languages, philosophy, law, economics and the sciences, with each noble palace telling its own story. On the left, at No. 20, is the senatorial 16th-century Palazzo Magnani * [map]; its hall of honour is decorated with a stunning cycle of frescoes depicting the The Story of the Foundation of Rome (1592) by the three Carracci painters, Annibale, Agostino and Ludovico. The two brothers and their cousin worked collaboratively in their early careers and it is not easy to work out their individual contributions. The palace is the seat of UniCredit Bank but the frieze can be seen on request, at no charge − telephone one day in advance on 051-296 2508.

The ornate Medicine faculty at the university

Getty Images

San Giacomo Maggiore

Across the road lies Piazza Rossini, named after the composer who studied for three years (1806−9) at the Conservatorio G.B. Martini on the piazza. His first compositions and public performances date from this time, including a historic concert with the opera singer Isabella Colbran whom he married in 1822.

Overlooking the square is the church of San Giacomo Maggiore ( [map] (Mon−Fri 7.30am−12.30pm and 3.30−6.30pm, Sat−Sun 8.30am−12.30pm and 3.30−6.30pm; free), known as the Bentivoglio family’s church. The Romanesque facade and portals flanked by lions pre-date Bologna’s grandest dynasty but the elegant Renaissance portico dates from their era, as do many of the superb paintings in their family chapel (follow the sign as you enter the church). Although only open on Saturday morning (9.30am−12.30pm) the chapel can be seen through the railings and illuminated by inserting a 50 cent coin. The Madonna and Child (1488) and the eerie Triumph of Death and Triumph of Fame are all by the Ferrarese painter Lorenzo Costa who worked in Bologna before succeeding Mantegna as the principal painter at the Gonzaga court at Mantua. The Madonna and Child (the Bentivoglio Altarpiece) features Giovanni il Bentivoglio, his wife and eleven children and was allegedly commissioned in thanksgiving for the family’s escape from an attempted massacre by a rival family. The Madonna and Saints (1494) by Francesco Raibolini, better known as ‘Il Francia’, is generally regarded as the best of the artist’s many altarpieces.

Oratorio di Santa Cecilia

Lorenzo Costa, Il Francia and contemporaries also worked on the Oratorio di Santa Cecilia , [map] (daily Oct−May 10am−1pm and 2−6pm, June−Sept 10am−1pm and 3−7pm; free but donations welcome) which adjoins San Giacomo Maggiore and is accessed via the portico. This little gem was built in 1267 but remodelled by the Bentivoglios who commissioned the artists to portray the Life and Martyrdom of St Cecilia, patron saint of music. The lively but little known Renaissance fresco cycle starts with Cecilia’s wedding (far left) and ends with her burial (far right). The scenes are accompanied by the bold statement ‘the night after her marriage to a pagan youth, Cecilia revealed that she had taken a vow of chastity and persuaded her husband to convert as she was a bride of Christ’. Even so, the bride met a sticky end, boiled alive, then beheaded as portrayed in the gory decapitation scene on the left as you enter. St Cecilia is patron saint of music so it is appropriate that classical concerts (free of charge) are held in the oratory.

Teatro Comunale

Alamy

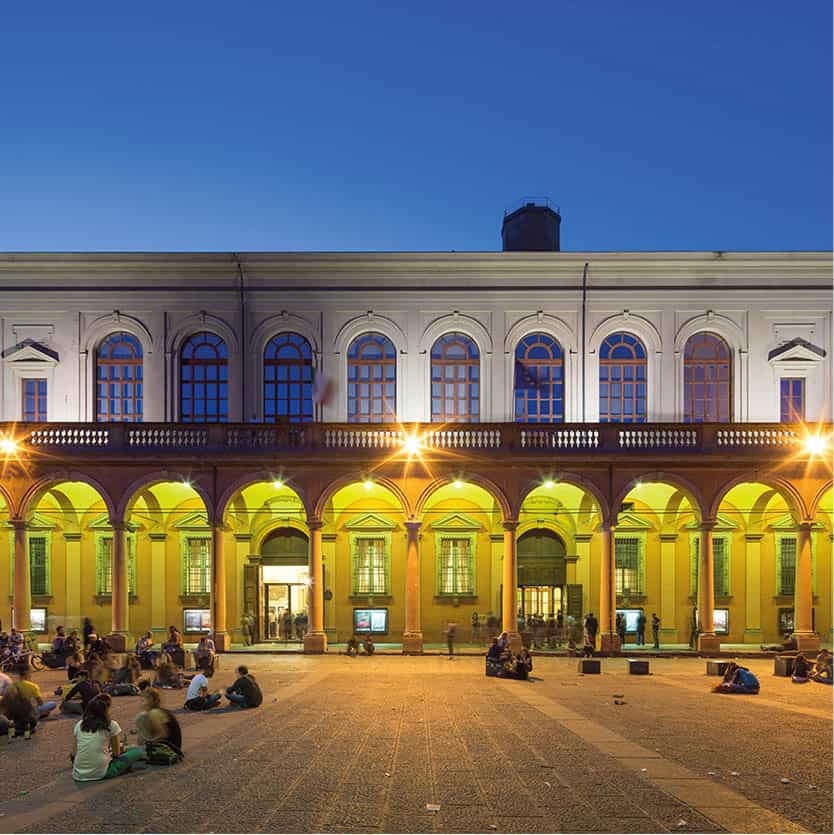

Piazza Verdi and Teatro Comunale

Further along Via Zamboni, Piazza Verdi ⁄ [map] is a hub of student life. Café Scuderia, with tables spilling out onto the square, is all about chilling out over cheap coffee or beer. Music often wafts from the Teatro Comunale ¤ [map] (www.tcbo.it), the opera house overlooking the square. Originally called the Nuovo Teatro Pubblico, the theatre was built to replace the wooden Teatro Malvezzi destroyed by fire in 1745. In Renaissance times this was the site of the sumptuous, 244-room Palazzo Bentivoglio, which was sacked and destroyed in 1507 by the masses who had become discontented with the rule of the Bentivoglio dynasty. The adjoining Via Guasto (guasto meaning ‘breakdown’ or formerly ‘devastation’), and the modern Giardini del Guasto derived their names from the ruins that laid here for decades. The 1930s facade of the Teatro Comunale belies an elegant Baroque-style interior with tiers of boxes (no access apart from performances). Many of these were formerly owned by titled families, each one individually decorated and bearing the family’s coat of arms on the ceiling. The opera house played host to 20 operas by Rossini, who lived for many years in Bologna, as well as historic performances such as the premiere of Gluck’s Il Tronfio di Clelia and the Italian premiere of Verdi’s Don Carlo in 1867. It was also receptive to works of composers outside Italy and was the first Italian opera house to stage a Wagner opera, Lohengrin, in 1871. Today it is the city’s main venue for opera (November to April), classical concerts and ballet.

Museum of Human Anatomy exhibits inside the Palazzo Poggi

Shutterstock

Palazzo Poggi

In 1803 the university moved from the Archiginnasio (for more information, click here) to the 16th-century Palazzo Poggi ‹ [map] (Via Zamboni 33; Tue−Fri 10am−4pm, Sat−Sun 10am−6pm; charge only for guided visits of the Specola, the Observatory, for which online reservations are required at http://museospecola.difa.unibo.it). This opulent seat of the university, decorated with Mannerist and early Baroque frescoes, is home to a confusing yet fascinating cluster of university museums. In the 17th and 18th centuries, this was the leading scientific institute in Europe, based on Bologna’s history of scholarship, particularly in anatomy and astronomy. A visit to the Specola tower on a guided tour (in Italian and English) is highly recommended; it also includes the Specola Museum and its rich collection of instruments for astronomical studies such as medieval astrolabes and celestial and terrestrial globes. The tower was built on top of the building and served as an astronomical observatory.

The collections in the university served primarily for research rather than as attractions for visitors, but it’s worth wandering through the vaulted frescoed galleries, with cycles of 16th-century frescoes, and picking out a few curiosities. Exhibits (many of which now have labels and explanations in English) range from models of military architecture and reconstructions of 17th-century warships to precious manuscripts and Japanese woodcuts. But the invariable magnets are the Museums of Obstetrics and Human Anatomy. Set up for teaching surgeons, doctors and midwives in the 18th century the collection includes a birthing chair on which students would practise blindfold as well as terracotta and wax models of wrongly-presented foetuses and gruesome models of human dissections.

There is more to see on Via Irnerio to the north of Palazzo Poggi: the university’s Botanical Garden, Museum of Physics (currently closed) and the L. Cattaneo Museo delle Cere Anatomiche (Museum of Anatomic Wax Models; June−Aug Mon−Fri 10am−1pm, Sat−Sun 10am−6pm, Sept−May Mon−Fri 9am−1pm, Sat−Sun 10am−6pm; free) at No 48, with more waxwork teaching aids, including models of faces with small pox and tumours, human intestines and conjoined twins.

Marconi: Bologna’s Wireless Pioneer

Among Bologna University’s famous alumni is Guglielmo Marconi (1874−1937), known for his pioneering work on long-distance wireless communication. He was born in Bologna in 1874 to a wealthy Italian landowner and his Irish-Scots wife but when Italy showed no interest in his experiments or requests for funding he moved to the UK. At the age of 27 he succeeded in receiving the first transatlantic radio signal which led to a worldwide revolution in telecommunications. In 1909 Marconi shared the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on wireless telegraphy. His Marconi Company radios saved hundreds of lives, including the 700 surviving passengers of the sinking Titanic in 1912. Bologna’s airport was named after him in 1978. Some of Marconi’s earliest experiments were completed at the family home, Villa Griffone at Pontechhio Marconi, 15km (9 miles) from Bologna, now home to the Marconi Museum (www.museomarconi.it; guided tours, reservation only).

A painting depicting medieval Bologna at the Pinacoteca Nazionale

Getty Images

Pinacoteca Nazionale

Just north of Palazzo Poggi, on Via delle Belle Arti is the Pinacoteca Nazionale › [map] (National Art Gallery; www.pinacotecabologna.beniculturali.it; Sept−June Tue−Sun 9am−7.30pm, July−Aug Tue−Wed 8.30am−2pm, Thu−Sun 1.45−7.30pm), the finest treasure house in the city. The National Gallery’s only flaw is its tendency to close sections for ‘lack of personnel’. Created during the Napoleonic occupation, the museum displays paintings plucked from demolished or deconsecrated churches. As was his wont Napoleon stole many of the finest treasures for the Louvre but Bologna managed to get them back in 1815. The gallery follows the path of Bolognese and Emilian art from the Middle Ages to the 18th century, but also includes works by artists from Florence, Tuscany and other ‘foreign’ parts, showing the influence on local artists.

The itinerary begins with works by Bolognese artists of the 14th century, and notably the vigorous and brilliantly coloured St George and the Dragon (c.1335) by Vitale da Bologna. Though cast in Byzantine-influenced Gothic mould, this dramatic, stylised scene shows the realism and expressiveness typical of Trecento Bolognese art. Other gallery scene-stealers are Giotto’s luminous polyptych Madonna and Child with Saints, which takes pride of place in Room 3 as one of only three panel paintings in the world signed by the artist, and Raphael’s Santa Cecilia (c.1515) in Room 15. This late altarpiece depicts the early Christian martyr and patron saint of music in ecstasy as she listens to a choir of angels in company of saints and Mary Magdalene. It was commissioned for a chapel dedicated to the saint in Bologna’s Augustinian Church of San Giovanni in Monte; from the same church came Parmigianino’s Madonna and Child with Saints (c.1530) now opposite the Raphael.

Not to be missed are the works by the great Bolognese Baroque artists. Room 23 displays masterpieces by all three of the Carracci painters. The two brothers and their cousin worked collaboratively and their frescoes still adorn the greatest city palaces; but here the works by the individual artists highlight their differences in style as well as their similarities. Room 24 is dedicated to works by Guido Reni (1575−1642), including a portrait of his mother and the dramatic and skilful Massacre of the Innocents, distinguished by a bold use of colour and grace of line and form.

Bologna and the Baroque

The members of the Bolognese school exerted one of the main influences on Baroque painting in Italy in the 17th century. Agostino (1557−1602), Annibale (1560−1609) and Ludovico Carracci (1555−1619), two brothers and a cousin, were leading figures in the movement against the affectations of Mannerism in Italian painting. Much in keeping with the desires of the Counter Reformation they revived the tradition of solidity and grandeur of the High Renaissance, stressing rigorous draftsmanship from life. Annibale’s fame was such that he was called to Rome to decorate the Farnese gallery, considered in its time as a worthy successor to the frescoes of Michelangelo and Raphael. Guido Reni (1775−1642) was a pupil of the Carracci and was initially influenced by their classicising style. He left Bologna for Rome where he painted many of his finest works, but returned to his native city in 1613 to head a vast studio that exported religious works all over Europe.

In the 19th century the Bolognese painters fell from favour. The leading art critic, John Ruskin, described the school as having “no single virtue, no colour, no drawing, no character, no history, no thought”. Their status suffered from Ruskin’s attacks but the Carraccis and Guido Reni are now regarded among the greatest Italian painters of their age.

Wise words

“When Bologna stops teaching, Bologna will be no more”. The words of the Archdeacon of Bologna’s cathedral and head chancellor of the Studium (University) in 1687.

North and West of Centre

From the maze of streets in the former Jewish ghetto to a cluster of medieval palaces and museums, this area of northern Bologna is packed with cultural attractions. When you have had your fill of sightseeing, the main streets of Via dell’Independenza, Via Ugo Bassi and Via Rizzoli provide plenty of retail distraction.

An alleyway in the ghetto

Shutterstock

The Jewish Ghetto

Tucked into the triangle of Via Oberdan, Via Zamboni and Via Valdonica, in the shadow of the Due Torri, the former ghetto fi [map] is about mood rather than monuments. As a liberal, cosmopolitan city Bologna welcomed Jews who were booksellers and drapers, but in 1555, under papal rule, the ghetto was established. Unlike the crisply geometric street plan in ‘Roman’ Bologna this area is a warren of narrow alleys, predating the papal edict. Take Via de Giudei (Street of the Jews) to moody Via Canonica and Via dell’Inferno fl [map]. The appropriately named ‘Hell Street’ became a virtual prison as only doctors were allowed to leave the ghetto at night. A plaque records the Holocaust but makes no reference to the expulsion of the Jews from here in 1593. The lofty buildings in Via Valdonica reflect the fact that the ghetto could only expand upwards. Recent gentrification has turned these tall tenements into desirable designer pads, so Hell Street is now a prestigious address − and one with a growing number of artisan workshops such as Calzoleria Max & Gio at No 22A, creators of fine, made-to-measure shoes for men. The Palazzo Pannolini at 1/5 Via Valdonica is home to the Museo Ebraico (Jewish Museum; www.museoebraicobo.it; Sun−Thu 10am−6pm, Fri 10am−4pm) which aims to preserve, study and promote the cultural Jewish heritage of Bologna and the Emilia Romagna region. The history of the Jewish population is analysed through multi-media exhibits, documents and artefacts from former ghettos.

The cathedral’s lofty interior

Getty Images

North of the ghetto, on Piazza San Martino is San Martino (Mon−Sat 8am−noon and 4−7pm, Sun 8.30am−1pm and 4−7pm; free), a Carmelite church remodelled in the 14th century along Gothic lines. A quick visit reveals fragments of a Uccello battle scene and paintings by notable Bolognese artists, such as the Carracci. Also in this area look up to spot sealed arches and other vestiges of medieval churches, deconsecrated in Napoleon’s day. But also expect signs for ‘happy hour’ and ‘tattoos’, proof that the university is nearby. Indeed, the square adjoins Via Goito, a popular place with students and a reminder that, for its size, Bologna has the greatest concentration of students in Italy.

Cattedrale Metropolitana di San Pietro

Via dell’Indipendenza was built to link the city centre and railway station in 1888. At its southern end the main landmark is the Cattedrale Metropolitana di San Pietro ‡ [map] (Mon−Sat 7.30am−6.45pm, Sun 8am−6.45pm; free). Despite its nominal cathedral status and monumental interior, San Pietro plays second fiddle to the basilica of the city’s patron saint, San Petronio. Architecturally and artistically it is certainly no match. In 1582 Pope Gregory XIII promoted the Bishop of Bologna to Archbishop and hence the cathedral rose to the rank of ‘metropolitan church’. It was remodelled to be a showpiece of papal power and apart from a few relics in the Crypt and the red marble lions from the original portal there is little trace of the original Romanesque-Gothic structure. Stroll down Via Altabella to see the soaring bell-tower which accommodates the ‘la nonna’ (grandmother), the largest bell playable ‘alla bolognese’, a form of full circle ringing devised in the 16th century but which is sadly disappearing.

Palazzo Fava

Along Via Manzoni, west of Via dell’Indipendenza, the Fava palazzi are among the finest in the city. At No 2, the Palazzo Fava-Ghisilieri is now known simply as Palazzo Fava ° [map] (www.genusbononiae.it; Tue−Sun 10am−7pm; access may be limited when exhibitions are not showing; combined ticket available for Palazzo Pepoli, Museo della Storia di Bologna and San Colombano and Tagliavini Collection). The palace was fully renovated as part of the Genus Bononiae project (for more information, click here) and reopened in 2011 as an exhibition centre. Blockbuster art shows are hosted here but it is also a treasure house of Carracci frescoes. In 1584 Filippo Fava commissioned Agostino, Annibale and Ludovico Carracci to decorate rooms on the piano nobile which gave rise to the first major fresco cycle of their career. This portrays the tragic tale of Jason and Medea and adorns the grand Sala di Giasone. Other halls of the palace were later decorated with scenes from Virgil’s Aeneid by Ludovico and his pupils. On the ground floor of the palace two rooms display changing exhibits from the art collection of the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Bologna.

Museo Civico Medievale

Next along is Palazzo Ghisilardi Fava, an archetypal Bolognese Gothic palace now home to the Museo Civico Medievale · [map] (Via Manzoni 4; www.museibologna.it/arteantica; Tue−Sun 10am−6.30pm), a non-fusty medieval museum whose superbly arrayed medieval and Renaissance treasures illuminate the cultural and intellectual life of the city. A graceful, galleried courtyard leads to a series of elaborately sculpted sarcophagi depicting the greatest medieval scholars, and notably the lecturers in law. The collection’s highlights are the coffered ceilings, stone statuary, gilded wood sculptures, and the monumental crosses that once adorned major city crossroads. Among many remarkable works are the Pietra della Pace, Stone of Peace by Corrado Fogolini, 1322, in Room 9, celebrating peace between the university and municipality following a period of conflict; the red marble tombstone of Bartolomeo da Vernazza (1348) in Room 11 and the statue of a Madonna and Child in polychrome terracotta by Jacopo della Quercia (1410) in Room 12. More specialist are the bronzes, weaponry, miniatures, medals and musical instruments. The vast and bizarre bronze statue of Pope Boniface VIII (1301) by Manno da Siena in Room 7 is a reminder of how the papacy liked to exert its power. Beyond the museum, at No 6, is the Casa Fava Conoscenti, one of the rare surviving tower houses, dating back to the 13th century.

San Colombano

Just to the west in Via Parigi the deconsecrated Church complex of San Colombano º [map] (www.genusbononiae.it; Tue−Sun 11am−7pm; combined ticket available for Palazzo Pepoli, Museo della Storia di Bologna and Palazzo Fava) makes a beautiful setting for the Tagliavini Collection of historical musical instruments. The late medieval church, decorated with faded frescoes, underwent major restoration before opening in 2010. Over 80 instruments are on display, among them spinets, harpsichords, clavichords and other keyboard instruments dating back five centuries and amassed by Bolognese musician and scholar, Luigi Ferdinando Tagliavini. Remarkably the instruments are all kept in perfect working order, played regularly and used for free monthly concerts from October to June. Among them are unique pieces such as an early 18th-century folding harpsichord and an earlier harpsichord with beautiful landscape decoration inside and out. The Oratory on the upper level displays a cycle of frescoes by the School of Carracci. Restoration works revealed the remains of a medieval crypt (accessible to the public) below the church, with a 13th-century mural Crucifixion attributed to Giunta Pisano and displayed behind glass.

A Subterranean Serenissima

It might not look like Venice but Bologna has an intricate network of over 60km (37 miles) of waterways, most of them running underground. From medieval times water was the source of economic progress and prosperity. The waters of the Savena, Reno and Aposa rivers were harnessed into canals both for domestic use and to provide energy for trades, particularly for the mills of the flourishing textile industry. Bologna became a leading silk producer in the 15th century and at the height of the industry had over 100 silk mills. The waterways were filled in during the 19th century but a port on the Navile Canal took goods and passengers down to the Po River and on to Venice, a system that served the city until the early 20th century. For a glimpse back into the era of waterways head for the Via Piella, just south of Piazza VIII Agosto, where the picturesque view over the Reno Canal from the little ‘window’ on the bridge gives a fleeting impression of Venice. For self-guided waterway-themed tours visit www.bolognawelcome.com, and for guided tours (in English and Italian) www.amicidelleacque.org.

Until Via dell’Indipendenza supplanted Via Galliera in 1888, this was the city’s most majestic boulevard, built over a Roman road. The arcaded street is lined with noble palaces dating from the 15th to the 18th century. Here, as elsewhere, many of the terracotta-hued porticoes are built of recycled Roman and medieval bricks with decorative motifs in baked clay. The street runs north to the striking Porta Galliera (gateway), repeatedly destroyed and rebuilt five times between 1330 and 1511.

MAMbo

On the northwestern edge of the centre, transformed from a former municipal bakery which supplied bread to the Bolognesi during World War I, is MAMbo ¡ [map] (Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna, Bologna Modern Art Museum; Via Don Minzoni 14; www.mambo-bologna.org; Tue, Wed and Fri−Sun 10am−6.30pm, Thu 10am−10pm). The museum forms part of the new cultural Manifattura delle Arti complex, transformed from the old harbour and industrial area of the city.

Bologna Museum of Modern Art (MAMbo)

Alamy

MAMbo hosts temporary exhibitions and has a permanent collection tracing the history of Italian art from World War II to the present day. It is also temporary home to the Museo Morandi − transferred from Palazzo d’Accursio in the centre while its galleries are undergoing restoration. Georgio Morandi (1890−1964) was one of the great still-life painters of modern times. This collection spans his Cézanne-influenced early works, his moody landscapes and his enigmatic bottles and bowls. Some of his less-opaque works are landscapes of the Bolognese hills, where the artist withdrew in the face of Fascism. Morandi fans can also now visit the recently restored house where Morandi lived and worked for most of his life, the Casa Morandi at 36 Via Fondazza, on the southeastern edge of the city (visits by appointment only, tel: 051-649 6611 or casamorandi@comune.bologna.it).

Pick up a picnic

The covered Mercato delle Erbe at Via Ugo Bassi 25 (www.mercatodelleerbe.eu) is a great place for picnic supplies with its salumerie (for prosciutto and cheeses), bakers, enotecas and huge range of fresh fruit and veg. Alternatively there’s a popular food court with a range of freshly prepared, affordable dishes.

San Francesco

Feeling far removed from the city bustle, to the west of the centre is the Gothic San Francesco ™ [map] (daily 6.45am−noon and 3.30−7pm; free). Despite radical restoration and serious damage during Allied bombardments in 1943, the Franciscan church remains one of the most beautiful in the city. Completed in 1263 it is now admired for its rebuilt Gothic facade, ornate altarpiece and Renaissance tombs, including, in the left aisle, the tomb of Pope Alexander V who died in Bologna in 1410. The precious marble altarpiece depicting saints and naturalistic scenes from the life of St Francis was the work of the Venetian artists, Pier Paolo and Jacobello dalle Masegne (1393). Outside, on the street side of the church, are the four raised Tombs of the Glossatori (legal annotators) dating from the 13th century. Before the university had a fixed abode students attended lectures in monastic churches, including this one, where medicine and arts were taught. The university’s presence lived on in the tombs of these illustrious doctors of law and medicine.

The Fiera district

Northeast of centre the Bologna Exhibition Centre (www.bolognafiere.it) was built in 1961−75 beyond the ring road. It extends over 375,000 sq m (4,036,466 sq ft) and hosts around 30 exhibitions a year. During the most popular shows hotels in Bologna are booked up months in advance.

South of the Centre

The cultural highlight of this quarter, south of the centre, is San Domenico, a convent complex and treasure house of art. The winding Via Castiglione at its northern end is lined by imposing mansions from various eras including the fortress-like medieval Palazzo Pepoli, recently reinvented as a modern history museum. Many of the terracotta-hued palazzi afford glimpses of vaulted courtyards, sculpted gateways and richly frescoed interiors. West of San Domenico Via Marsili and Via d’Azeglio form part of the city’s passeggiata, or ritual stroll, a chance to see the city at its most sociable.

Fiera district architecture

Shutterstock

The Piazza della Mercanzia south of the Due Torri feeds into the noble end of Via Castiglione. Both this street and Via Farini, an elegant shopping street, conceal waterways. The canal network linked to the River Po and the Adriatic generated the power for the silk and paper mills, brickworks and tanneries and for the millers, dyers and weavers who were the mainstay of the medieval economy. But when the district was gentrified in the 16th century, the nobility scorned these murky waters. Although finally covered in 1660, the canal still runs below Via Castiglione which explains why the pavements resemble canal banks.

The austere medieval facade of the Palazzo Pepoli Vecchio at No 8 Via Castiglione belies a brand new interior, home to the Museo della Storia di Bologna # [map] (Museum of the History of Bologna; www.genusbononiae.it; Tue−Sun 10am−7pm; combined ticket available for Palazzo Fava, Palazzo delle Esposizioni and San Colombano and Tagliavini Collection for more information, click here or click here). The grandiose palace was built as the seat of the Pepoli, lords of Bologna in the mid-14th century, but was not completed until 1723. The interior underwent a total transformation in 2012 to become an innovative, interactive museum, dedicated to the historical and cultural heritage of Bologna. The tour spans 2,500 years of the city’s distinguished history, focusing around the futuristic steel and glass Torre del Tempo (Tower of Time) which rises up from the courtyard. Through 3D films (and cartoons), mock-ups of Etruscan and Roman roads, photos and multimedia installations, the museum traces the evolution of the city from the Etruscans to the present day. The lively modern displays tend to attract more school groups and students than tourists and most of the labelling and videos are in Italian (though there are information sheets in English in most rooms).

Genus Bononiae, Museums in the City

The Museo della Storia di Bologna is one of the eight cultural attractions on the ‘Genus Bononiae Museums in the City’ itinerary (www.genusbononiae.it). The route takes in some of the city’s most important churches and palaces that have been completely renovated for public use. Apart from one, all are within easy walking distance in the city centre. The attractions include the Palazzo Fava (for more information, click here) and the churches of San Colombano with the Tagliavini Collection (for more information, click here), Santa Maria della Vita (for more information, click here) and Santa Cristina, where concerts are held. Just out of town is San Michele in Bosco, a former monastery on a hill overlooking the city. The churches and palaces on the itinerary are managed, and some also owned by, the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Bologna, a non-profit-making bank foundation.

Basilica di San Domenico

As you walk south along the Via Castiglione, the mood becomes subtly more domesticated. This was the key route to the Bolognese hills and access here was controlled by Porta Castiglione, one of ten surviving city gates. To the west the monumental Basilica di San Domenico ¢ [map] (Mon−Fri 9am−noon and 3.30−6pm, Sat 9am−noon and 3.30−5pm, Sun 3.30−5pm; charge for presbytery only) dominates the cobbled Piazza San Domenico. The two mausoleums on the square, each with its tomb raised on pillars and protected by a canopy, celebrate renowned medieval law scholars Rolandino de’ Passaggeri and Egidio Foscherari.

The Basilica di San Domenico, at the foot of the Bolognese hills

Shutterstock

The Basilica was built to house the relics of San Domenico, founder of the Dominican order, who died here in 1221 when it was just the small church of San Nicolò of the Vineyards on the outskirts of Bologna. He was canonised in 1234 and his remains lie in an exquisite shrine within the church. The Dominican foundation was built in 1228−38 but was remodelled in Baroque style. Although it has lost much of its late Romanesque and Renaissance purity it abounds in curious, canopied tombs and artworks by such luminaries as Michelangleo, Pisano and Filippino Lippi as well as by leading Bolognese artists. The Cappella di San Domenico (Chapel of St Dominic) holding the saint’s tomb is half way down the basilica on the right. The spectacular Arca di San Domenico (Tomb of St Dominic) is the work of various leading artists, among them Niccolò da Bari − who acquired the name Niccolò dell’Arca following his highly acclaimed work on this tomb − Niccolò Pisano and Arnolfo di Cambio, both of the Pisan School. Niccolò da Bari died in 1492 and the Arca was completed by Michelangelo (a mere 19 years-old at the time) who carved two Bolognese saints, St Proculus and St Petronius holding a model of Bologna, and the angel on the right of the altar table holding up the candelabra. Above the Arca, Guido Reni’s St Dominic in Glory with Christ, the Madonna and Saints decorates the dome, and hidden behind the shrine lies the precious reliquary of the head of St Dominic. Among the many other art works are the Crucifix (1250) by Giunta Pisano and the tomb of Taddeo Pepoli both in the left transept, the Mystical Marriage of St Catherine by Filippino Lippi in the small chapel beyond the right transept and the beautiful mid-16th-century marquetry choir stalls.

Piazza San Domenico, graced by a statue of the saint

Alamy

Via d’Azeglio

In the late afternoon and early evening the pedestrianised Via d’Azeglio ∞ [map], west of San Domenico, is known as il salotto, or drawing room − the place for chatting over cocktails and designer shopping. It is a relaxed mix of happy families and glamorous Bologna per bene − the smart set. There are big-name boutiques here but the most sought-after shops are in neighbouring Galleria Cavour and Via Farini. The boldest of Bologna’s senatorial palaces stands at No 31 − the 15th-century Palazzo Bevilacqua (No 31) in Tuscan style, with a rusticated sandstone facade, wrought iron balconies and a courtyard surrounded by a loggia. Here the Council of Trent met for two sessions in 1547 after fleeing an epidemic in Trent.

Bologna’s beloved Lucio Dalla

If you happen to be in Via d’Azeglio at 6pm, you will hear the music of Lucio Dalla (1943−2012), the much-loved Bolognese singer-songwriter (his Caruso sung by Pavarotti sold nine million copies). The music is streamed from Via d’Azeglia 15, where Dalla lived. His funeral was held in the Basilica of San Petronio and over 50,000 people came to the Piazza to bid him farewell.

Tucked away in a corner west of Via d’Azeglio and off Via Collegio di Spagna lies a curious Spanish enclave. The crenellated Collegio di Spagna (visits only on request) was founded in 1365 by Cardinal Gil de Albornoz (representing the papacy) and bequeathed to Spanish scholars at Bologna University in 1365 as a glorified hostel. It continues to fulfil this function today, under the auspices of the Spanish Crown. Close by is the Caffè de la Paix, a café as peaceful as it sounds, with a special welcome for Spanish scholars. To the north east, on the corner of Via Val d’Aposa and Vicolo Spirito Santo, the Spirito Santo (no admission to the public) is an exquisite jewel-box of a church. Under the medieval streets here runs a secret river, the d’Aposa.

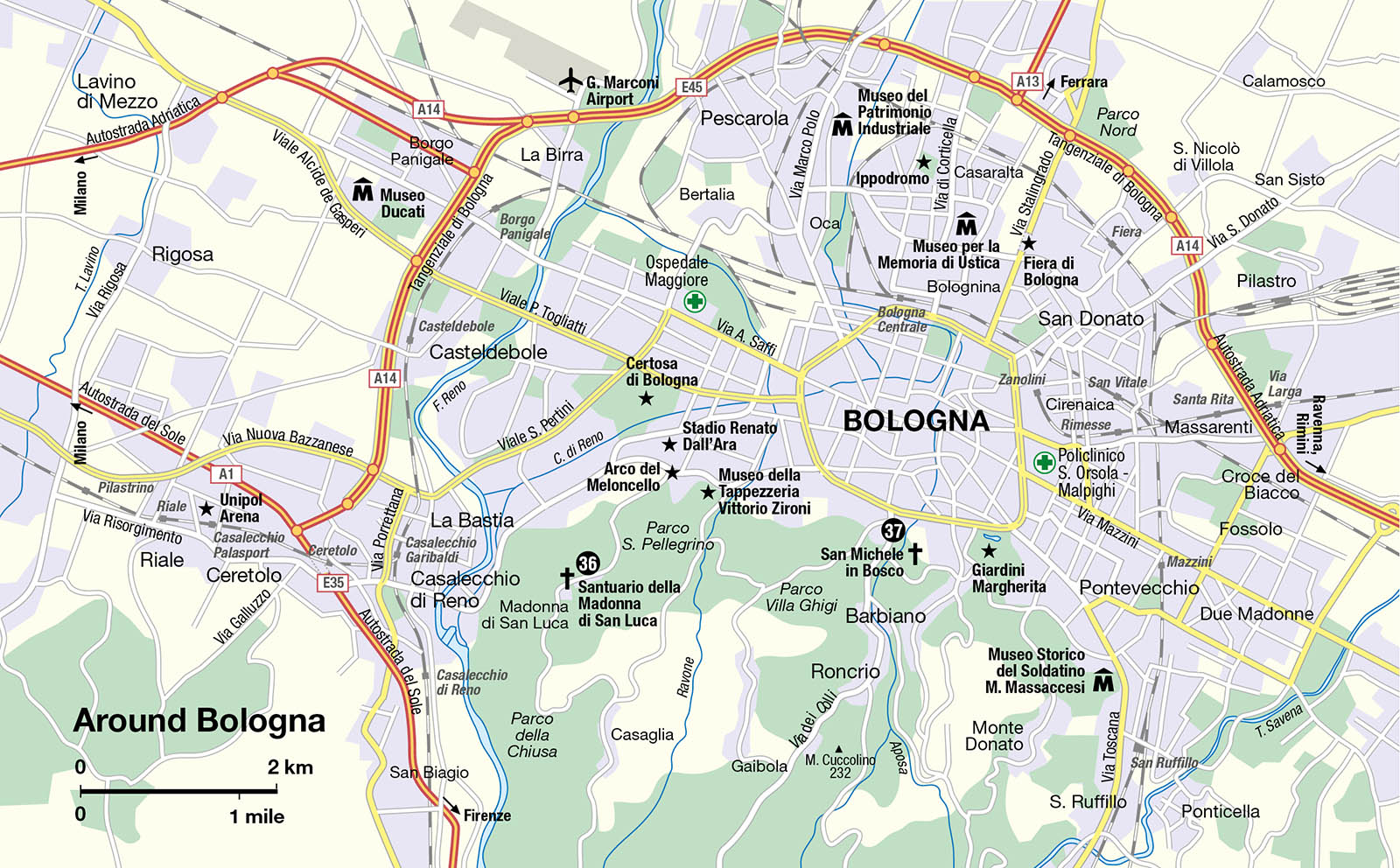

The Bologna Hills

Crowning a hilltop to the southwest of the city and linked to it by the world’s longest portico is the famous Santuario della Madonna di San Luca § [map] (Mar−Oct Mon−Sat 7am−12.30pm and 2.30−7pm, Sun 7am−7pm, Nov−Feb until 6pm; church: free, terrace: donation). Dating from 1732 the conspicuous pink basilica took 50 years to build, is 3.8km (2.3 miles) long, has 666 arches and winds its way up from Piazza di Porta Saragozza. You are rewarded at the top with fine views of the Apennines. (If you don’t fancy the whole hike take bus No 20 to the Arco Meloncello and walk from there or take the little tourist train from the centre in season.) The 18th-century sanctuary is richly decorated and houses a much-revered Byzantine-style image of the Madonna, probably dating from medieval times but once believed to have been painted by St Luke. Every Ascension Week she is taken down the hill to the Cathedral of San Pietro, with crowds lining the Via Saragozza to see the procession go by. The church brings barefoot pilgrims and other worshippers as well as joggers and cyclists who go up the hill to work off the pasta.

Lording it over Bologna to its south is San Michele in Bosco ¶ [map] (daily 8am−noon and 4−6pm; free; 30 mins on foot or take No 30 bus), a religious complex with an annexed monastery that has served as an orthopaedic hospital since 1880. The Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Bologna now manages the vast area, including the octagonal cloister and library, and the church complex features on the Genus Bononiae museum itinerary (for more information, click here). The sweeping views, which were admired by Stendhal when he passed through Bologna in 1817, embrace the entire city.

You’ll never go hungry in Bologna

Shutterstock

Excursions from Bologna

With excellent rail links Bologna makes a good base for excursions to the handsome historic cities of Emilia-Romagna. (It is only around half an hour to Modena and Ferrara, an hour to Parma, 80 mins to Ravenna, 60−90 mins to Rimini). Apart from culture, the region is a gourmet’s delight and many visitors come on gastronomic tours taking in artisan producers of Parma ham, Mortadella, traditional balsamic vinegar of Modena, Parmigiano Reggiano − as well as local wine producers. The Langhirano valley is home to around 500 authorised producers of the famous prosciutto crudo di Parma, many open to the public for tastings and purchases. On plains north of Parma there are Parmesan cheese-making cooperatives and around Modena balsamic vinegar distilleries where the vinegar is aged in wooden barrels for up to 25 years.

Parma

Parma • [map] is a byword for fine living, from Parmesan and Parma ham to music and Mannerist art. At the heart of the city a network of quiet old streets opens on to the harmonious Piazza Duomo where the Lombard Romanesque Cathedral (www.piazzaduomoparma.com; daily 10am−6pm; church: free, baptistery: charge) and the graceful rose marble Baptistery form a fine ensemble. Inside the cathedral, decorating the central dome in a triumph of trompe-l’œil, is Corregio’s great masterpiece: the Assumption of the Virgin (1526−30). This boldly illusionistic work, Corregio’s last fresco, paved the way for Baroque art but found little favour with the church. The neighbouring Baptistery (daily 10am−6pm) is a jewel of the Italian Romanesque − a beautiful octagonal building with elaborately carved reliefs on the exterior and portals by sculptor and architect, Benedetto Antelami (1150−1230). The interior is an illuminated manuscript awash with vividly coloured 13th-century biblical scenes, influenced by Byzantine art. Antelami and his assistants created the series of sculptures, showing the seasons, the signs of the zodiac and the labours of the month. The masterly Antelami is also believed to have been the architect of the Baptistery.

Frogs’ legs fresco

A canon of Parma’s cathedral criticised Corregio’s fresco of the Assumption of the Virgin as ‘a stew of frogs’ legs’, but Titian, recognising the artist’s triumph of illusionism, decreed that if the dome were turned upside down and filled with gold it would not be as valuable as Correggio’s frescoes.

Al fresco dining in Parma

Getty Images

Behind the cathedral the 16th-century Renaissance church of San Giovanni Evangelista (daily 8.30−11.45am and 3−6pm) with a Baroque facade also has a cupola decorated with a fine Correggio fresco: The Vision of St John on Patmos, depicting Christ descending to John. Northwest of Piazza del Duomo, in a former Benedictine convent, the Camera di San Paolo (Mon−Sat 1.10−6.50pm) was one of the private rooms in the apartments of the unconventional and learned Abbess of San Paolo, called Giovanna da Piacenza. In 1519 she commissioned Correggio to decorate the room with a feast for the senses, including mischievous putti and a view of Chastity as symbolised by the goddess Diana. It was Correggio’s first large-scale commission in Parma.

The Palazzo della Pilotta on Piazzale della Pace is the city’s cultural heart and home to the Galleria Nazionale (Tue−Sat 8.30am−7pm, Sun 1−7pm) with works by locals such as Correggio and Il Parmigianino, along with Venetian, Tuscan and other Emilian artists. The palazzo also houses the archaeological museum, housing pre-Roman and Roman artefacts, the Palatine Library and the Teatro Farnese, an imposing wooden theatre with a revolving stage, based on Palladio’s masterpiece, the Teatro Olimpico at Vicenza. It is still used for theatrical performances.

Modena

Modena ª [map] is the home of Pavarotti, Maserati and Ferrari, and its wonderfully preserved historic centre is Unesco-listed. Yet it is rarely visited by tourists. The success of the food, sleek Ferrari cars and ceramics industries has been instrumental in making tourism a mere after-thought in this cosseted land of plenty. A morning’s sightseeing in the historic centre could be followed by a meal at an osteria ranking No 1 in the World’s 50 Best Restaurants (in 2018) (for more information, click here and reserve well in advance), then perhaps a visit to a traditional balsamic vinegar distillery, Acetaia di Giorgio (Via Cabassi 67; www.acetaiadigiorgio.it) to learn the tricks of the trade and taste the unctuous Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena vinegar.

Modena’s Piazza Grande, dominated by the Romanesque Duomo

Shutterstock

Modena’s city centre is dominated by the Duomo (daily 7.30am−12.30pm and 3.30−7pm) one of the masterpieces of the Italian Romanesque for both its architecture and sculpture. The grandiose marble cathedral and adjoining bell tower are Unesco World Heritage Sites. In a tribute, rare for the 12th century, the names of both the architect, Lanfranco, and the master sculptor, Wiligelmo da Modena, are recorded on inscriptions on the facade. Countess Matilda of Tuscany, ruler of Modena, commissioned Lanfranco, the greatest architect of the time, to mastermind the cathedral which would house the remains of St Geminiano, patron saint of the city. Wiglielmo equalled him in creating the exuberant friezes of griffins and dragons, peacocks and trailing vine leaves. On the southern side, the main portal is flanked by stylised Roman-style lions; over the doorway on the left is Wiglielmo’s finest work, the depiction of the Creation and Fall of Adam and Eve. On the northern side the sculptured Porta della Pescheria is decorated with the cycle of the months. The softly lit interior reveals brick-vaulted naves and such treasures as the rood-screen, a Romanesque masterpiece, as well as the crypt sculpted by Wiglielmo. Alongside the apse rises the leaning Torre della Ghirlandina, the octagonal 12th-century bell tower built with slabs of marble recycled from Roman ruins.

To the northwest of the cathedral, on Piazza Sant’Agostino, stands the Palazzo dei Musei (www.museicivici.modena.it) where the d’Este court amassed Modena’s finest art collection and library and now hosting the city’s museums and art galleries. The most interesting are the Galleria Estense (www.gallerie-estensi.beniculturali.it; Tue−Sat 8.30am−7.30pm, Sun 2−7.30pm), a rich collection of works by Emilian, Flemish and Venetian artists, and the Biblioteca Estense which displays rare manuscripts, seals and maps, as well as the priceless Bibbio Borso, the beautifully illustrated bible of Borso d’Este, first Duke of Modena. On Piazza Roma, northeast of the cathedral, the austere and immense Palazzo Ducale (Ducal Palace) was the former court of the d’Este dynasty. It is now Italy’s top military academy, with no access for the public, but the ducal park behind has been converted into public and botanical gardens.

Pavarotti’s house

The House and Museum of Luciano Pavarotti, 8km (5 miles) from the centre of Modena (www.casamuseolucianopavarotti.it) gives a glimpse into the life of the late maestro. Opened in 2015, it displays personal memorabilia and recordings of great performances.

Ferrari, Maserati and Lamborghini sports cars are all produced in Modena so a passion for speed goes with the territory. Enzo Ferrari founded his firm in 1939 and the company is still producing cars in the Maranello factories in the industrial outskirts. Modena now has its own Ferrari museum: the Museo Enzo Ferrari (https://musei.ferrari.com/en/modena) where Ferraris and Maseratis are displayed in a gigantic showroom and Enzo Ferrari’s fascinating life story is related in the converted workshop of his father. A regular shuttle bus connects the museum with Maranello (20km/12.5 miles from Modena) where the Museo Ferrari (https://musei.ferrari.com/en/maranello) showcases the world’s largest collection of Ferraris, with models through the ages − and a simulator where visitors can experience driving a Ferrari single-seater on the Monza track. Every Ferrari victory in the Grand Prix is celebrated by the priest ringing the bells of the Maranello parish church − which gives you some idea of the fanaticism of the locals.

The gleaming Museum Enzo Ferrari in Modena

Shutterstock

Ferrara

Beguiling Ferrara q [map] was a stronghold of the high-living dukes of Este – archetypically scheming, murderous, lovable Renaissance villains who ruled from 1200−1600 and from Ferrara-controlled territory embracing Parma, Modena and Garfagnana in Tuscany. During its Renaissance heyday, the dynasty drew artists of the stature of Piero della Francesca and Mantegna, turning the Ferrara court into a ‘princely garden of delights’. From the 17th to the 19th century travellers found Ferrara something of a ghost town with few inhabitants and grass growing in the streets. However since its bombing in World War II the city has revived and in 1995 was declared a Unesco World Heritage Site.

The heart of the town is still dominated by the formidable Castello Estense (www.castelloestense.it; Oct−Feb Tue−Sun 9.30am−5.30pm, Mar−Sept daily 9.30am−5.30pm), a 14th-century moated fortress where guides tell delightfully dubious tales of what went on in the dungeons. As the d’Este dynasty’s seat the medieval fortress was gradually transformed into a gracious Renaissance palace but retains elements from both incarnations. Most of the artistic treasures were spirited away to Modena when Ferrara’s rival became the Ducal capital in 1598, and the great works of the Ferrarese school are dispersed in European public collections, notably the National Gallery in London. However the noble apartments retain some outstanding frescoed ceilings. To sample noble dishes dating back to the d’Este court, head for the Hostaria Savonarola in Piazza Savonarola, adjoining Castle Square. Try a plate of tortelli di ricotta or cappellaci di zucca, pumpkin-filled pasta parcels.

On your bike

Ferrara is Italy’s most bike-friendly city − there are 2.1 bikes per inhabitant. For bike-hire, cycling suggestions in the traffic-free centre and cycling tourism in the province (including the popular 100km/62.5 mile route that runs along the River Po towards the sea) visit www.ferraraterraeacqua.it.

South of the Castello Estense is the triple-gabled Romanesque and Gothic Cathedral (Mon−Fri 7.30−11am and 4−7pm, Sat 7.30am−noon and 3−7pm, Sun 7.30am−1pm and 3.30−8pm; free). The facade has rich sculptural detail: from the lunette of St George Killing the Dragon to the loggia and the baldachin adorned with sculptures of the Madonna and Child. The disappointing Baroque interior is redeemed by a Byzantine baptismal font and the museum, which holds sculptures by Jacopo della Quercia and two masterpieces by Cosmè Tura decorating organ shutters and representing The Annunciation and St George and the Princess. The Piazza della Cattedrale is best appreciated from the café terrace of the Pasticceria Leon d’Oro. The piazza comes alive during the Palio in May, a medieval tournament dating back to 1259, and the Buskers’ Festival in August, which is the biggest of its kind in the world.

The delightful Castello Estense in Ferrara

iStock