We who live in our heads are pretty familiar with the way the male aspect of our consciousness thinks when it becomes unipolar: identified with the mythological tyrant, it holds its logic independent of the Logos and, by consolidating the body, refuses to integrate experience. That consolidation—that construct of clenched muscle tissues and fixed idea that we have called the ‘known self’—also changes how we think and what we can think about. For simplicity’s sake, we might dub that dissociated thinking of our male consciousness the hetabrain mode. Heta, which sounds a little like ‘head’, is the name of the Greek letter from which we got our letter ‘H’, and the Greeks originally borrowed it from a Semitic letter that means “fence, barrier” in honor of its shape: H. In that meaning we find precisely the state of the consciousness that requires the ‘known self’: that mind-set seeks to fence the self in, so that its thinking can work from behind a barrier—a barrier that specifically rejects the female pole of its axis. For our purposes, then, we might be well enough served to say that when the male element of doing takes over, our experiences of self, body and world phase into the hetabrain mode.

We have already looked at how our experience of the body changes as it enters the hetabrain mode. We also have a sense that, as water is locked into crystals when it freezes, hetabrain thinking freezes the world into symbols or duplicates, which constitute its basic language of thought. We might consider furthermore that water represents a more energetic state than ice. Quite simply, you have to add energy to ice to melt it, or strip energy away from water to make it freeze. Something comparable occurs when we phase into hetabrain thinking. We have to strip energy away from a tree, for example—obviate its particular life, its individual expression, forget about its here-and-now process in which we share—to treat it with the foregone assumptions we would accord a symbol. When our knowledge about it is neat and tidy, what need is there to open to the energy of its particular reality? Similarly, we open the fridge to find the ketchup and don’t usually notice the ordinary qualities that make the bottle unique—we notice it generically. We notice people, insects, apples and birdsong in the same way. But when we strip energy away from the world, we also strip away its ability to energize us.

Each of us is at every moment standing in the river of the world’s energy. Either we choose to brace against it or we submit to it. The hetabrain braces against it in myriad ways, which we so take for granted that our reflex to resist is seen as normal, necessary and prudent. I learned a big lesson about such resistance from a little river in Ontario called the Coldwater River; and there is no question as to how it got its name. I was building a barn late one summer on a property through which the river ran, and I was determined to find a way of swimming in it that did not send my body into panic. Every evening over weeks I would walk down to the river, step into it, take the plunge, and face the panic. I was warm, the water was cold, and the panic was my way of trying to keep them apart. As I did that night after night, I came to realize that I wasn’t really feeling the water; I was too busy fortifying myself against it. Bit by bit it became easier and easier to enter the water until—as I have come to understand it now—I learned to release all the tensions in my body that were trying to secure the ‘known self’ against the cold, and instead let my body come to rest, whole and in the moment and resonant to it. When I was able to feel the body as a whole, I could walk into the rushing cold and submit to it, without resistance or prejudice or effort. The plunge was a kind of bliss, leading to a few moments of utter serenity beneath the swirling surface. And, quite contrary to what common sense would predict, once I was willing to feel the cold, I didn’t become cold. My body, unlocked and free to respond to the frigid currents, could adapt to them. Since then I’ve just as easily waded through shore ice to dive into a wintry lake; or through rush-hour crowds to enter a subway station. To release yourself from the divisions and effort of the hetabrain mode is to give yourself the chance of merging with the aliveness of the felt present around you; to allow yourself to transform—even while submersed in ice-cold water—is to allow yourself to remain whole. Resting, you change.

Furthermore, only by submitting to the energy of the world can you connect with the roots of your own Being, for those roots do not lie protected and static within you, but are living conduits that bring you into relationship and exchange with the world. By giving yourself over to the energy of the world, you are, in effect, unlocking your capacity for relationship. By fencing yourself off from that energy, you are cutting away your own roots.

The Tao Te Ching observed, “what is rooted is easy to nourish.”198 That metaphor comes alive for me when I think of running. There was a time when I would go out for a run and supervise my body to help it achieve its optimum pace. Eventually, slowly, I recognized the shimmering flux of energy all around me, and I found that if I just opened myself to its companionship, without design or specific aims—if I allowed all that energy to course into and through me—it would carry me the way a leaf is carried along by a river. As the isolated ‘doer’ melted into the space around me, I felt I was ‘being run’ rather than running. At its finest, such running opens me to a state of grace. But that possibility of grace is always available, whether running or standing still: to be present in the river of the world’s companionship is to be supported by its coursing energy. And although we can and do brace ourselves against it, there is in fact nowhere to stand but in that river—it is all we have. To open to it is to open to the grace of Being, which is the gift of life.

Man, we are told, has been given choice; and I think the choice that most fundamentally distinguishes humanity is the one that enables us to lock ourselves out of the world’s fluidity behind the walls of stubborn, insensate fantasy. No other animal seems able to do that so well. The ability is made possible by the simple fact that you cannot integrate unconscious flesh. Ultimately, then, the fence behind which the hetabrain retreats is constituted of just that: our own desensitized flesh. All the spheres of the ‘known self’ have that in common. In all of them, the mind’s sensitivity hides itself and calls that feat self-mastery. That is the choice that turns us away from the female, fragments our view of self and world, and relieves us of the inconvenience of feeling the present. It also enables us to forge such deep attachments to a set of ideas that we feel the truth of those ideas passionately and mistake ‘feeling an idea’ for ‘feeling the whole’. The advice to “live by your convictions” is certainly laudable up to a point, but it can all too easily become a slippery slope into obdurate insensitivity. Living in relationship to the world as a whole is a moment-by-moment revelation, an entirely different experience from living in relation to ideas about it. As a culture, though, we persist in trying to solve our problems by finding the right perspective on them, as though that is where redemption lies, as though we needn’t really bother with the messy business of integration. That tendency is not just wayward, but destructive. In fact, I think the most dangerous individuals are those who feel their convictions more intensely than they feel the newness of ‘what is’—whether their convictions concern corporate entitlement, religious ideology, social engineering or the solutions afforded by technology. Such rigid convictions exhort us to actions that are heedless of the whispering currents of the living present.

The way the felt self thinks is exactly what Parmenides so persuasively urged us to turn our backs on 2,500 years ago; so that even though we have all experienced its thinking in one way or another, it remains shrouded in shadows. In fact, that thinking remains precisely as obscure to us as our neglected pelvic intelligence, on which it largely depends. The thinking of the felt self finds its complement in the ever-moving, paradoxical process of the present: in its wild peace, its earth and sky, and in the abiding stillness that underlies its continuous transformations. Unlike the unipolar thinking of the ‘known self’—housed in the head—the axial thinking of the felt self occurs when the embodied corridor opens to a balanced interplay of exchange and renewal between its two poles; and then takes the next step of opening to the guidance of the world. When it does that, we begin to feel a second axis of consciousness, one through which the felt whole of the self comes into accord with the felt whole of the world. And just as perspectives are converted into sensation as they move along the embodied axis, our clear sense of ‘I’ is converted into a clear sense of ‘We’ as our consciousness opens along this second axis. But another, more curious thing also happens: sensations are converted into insights. How that happens, and what the nature of the second axis is, we can begin to understand by drawing a comparison from the recording industry: the differences between analog and digital recording technologies.

To begin with, the differences between those two technologies illustrate what the old lady was trying to explain to the novice Noh actor: digital technology is like “knowing the thing in part”; analog technology is like “feeling the thing as a whole.” How so? Collecting digital information is a lot like “copying facts point by point.” The information on a digital recording of music is compiled of samples that are collected 44,100 times per second. Each sample is like a snapshot: it measures one instant of the music and converts that measurement into a binary number. The process creates 44,100 discontinuities in each second of music we hear—the spaces between the snapshots—but who could ever hear such fleeting interstices? When all those snapshots are run sequentially—ten seconds of high-quality sound require almost half a million samples and more than seven million bits of information—we can create a duplicate that sounds convincingly like the real thing.

In an analog recording, nothing is measured or quantified—there are neither facts nor snapshots. To understand how an analog recording works, it helps to understand that sound is the energy of mechanical vibrations, which alternately compress and expand the air around them. Those vibrations travel as waves through the air, move the eardrum, and are heard as sound. The sensitivity of the ear is astounding: it can detect density changes of sound of less than one ten-millionth of one percent. Analog recordings store sound in impressions that are made by the original sound wave. On a vinyl LP, for instance, the original waveform of the music is physically shaped along the groove of the record, in the form of ripples along its walls. In making those grooves, the original sound wave moves the microphone, which sends an electric impulse to a cutter, moving it in the same way; the cutter creates a groove as it moves through a soft material and leaves behind the impression of the waveform. When you play an LP on a turntable, a stylus rides through the groove, and the ripples move the stylus, which recreates the waveform in another electric impulse, which is amplified and goes on to move the speaker in your living room.

It is easy enough to see how these different recording technologies correspond to the differences in thinking between the hetabrain and the felt self. Digital information is similar to unintegrated perspectives: as the hetabrain quantifies and consolidates perspectives into a static concept, so too a digital recorder quantifies perspectives on a waveform and consolidates them into a static sequence of numbers. Digital information is broken information—made of discrete, discontinuous facts. And in the same way that the young actor’s copied facts do not themselves resemble an old lady, the sequence of numbers does not resemble the music: both are abstract duplicates purified of life and cannot fulfill their function until they are interpreted. The word digital comes from an Indo-European base deik-, which means “to show,” and is related to our words judge, judicative, verdict and dictator. It came to us through a group of Latin words that conveyed the sense of “to point at,” the way you might indicate something with a finger. And that is reminiscent of Meister Eckhart’s observation that because an idea “always points to something else,” it cannot bless us. Metaphorically, then, we might speak of the intelligence of the hetabrain, which stands apart from the Energy of the world and indicates it with a system of duplicates, as ‘digital knowing’.

All of our senses are informed by analog impression rather than measurement: the world’s energy presses upon them, as the pressure of a door handle upon the palm of our hand. And much as a stylus is informed by the waveforms in a record groove, our senses are informed about the energy of the world by vibrations: the eye sees waves of light, the ear hears vibrations, and we feel heat and cold, wind and texture, all as vibrations. Similarly, the consciousness that joins self and world is analog, and the energetic potential for exchange between them might be named the analog axis. In the way that analog audio technology leans on the vibrating source—the music—and enables its waveform to shape the groove in the LP, the analog axis allows our sensitivities to lean on the One Source—the present—and receive the impression of all the subtle waveforms of Being. Taken together, those waveforms, those currents of exchange, are the one reality. On the subatomic level, even so-called ‘particles’ can be understood in those terms. Physicist Heinz Pagels explains,

The electron is not a particle … it is a matter wave as an ocean wave is a water wave. According to this interpretation … all quantum objects, not just electrons, are little waves—and all of nature is a great wave phenomenon.199

We might also say that Being is a great wave phenomenon—and that its every ripple conveys information. It is through vibrations that a baby in the womb learns about its world, which is first and foremost its mother. And as a baby belongs to and is immersed in the vibrations of its mother, we belong to and are immersed in the vibrations of the great maternal energy around us. When we clear the body of its rigid presumptions and consolidations and open our hearts to the world, then what passes through us is the humming reality of Being. The grace of the maternal harmony, the vibrations of the One Presence, traverse the analog axis and permeate our core. The vibrations of Being become our vibrations—the energy of the world felt within the body’s stillness. In its essence, the body is a vibratory medium—but only our receptivity to the great wave phenomenon we call ‘the present’ makes us aware of that, just as it is only through that receptivity that our analog axis is ushered into consciousness. It is of some interest to us, then, that our word vibrate is linked through the Indo-European base weib- to the English word woman, and also to a German word Wipfel, which literally means “the swaying part of a tree.”

Our analog axis enables us to feel the energy of the world; our digital knowing enables us to represent aspects of that energy with static ideas. As the touch of a finger will silence a tuning fork, the tyrannies that drive consciousness out of the body will silence our analog axis: quite simply, it becomes incapable of moving to the world’s subtle currents. When such tyranny advances sufficiently far, it reaches a threshold at which the unity of the present cannot be detected. When you can no longer detect the all-informing present, you no longer have reason to believe it can offer you guidance. The present then becomes a mere idea—one you can track by the number on your digital watch. Detached from the Logos, you devote your faculties of intelligence almost entirely to unintegrated perspectives; and then the meaningful currents of your own life slip between the discontinuities of your broken analysis of things as water will run through your cupped digits.

The word analog originally comes from roots that mean “according to the Logos.” To know any part of reality according to the Logos is to experience the living currents of that part directly, which themselves accord with the Logos: every wave of being contains inexhaustible information about the great wave phenomenon from which it arises. The impressions that pass through the analog axis are of the utmost sensitivity and speak to your heart; they speak as directly as a mother to her child; and they speak to a core that has fully surrendered to the present—either through a self-achieved submission that razes the fence of the hetabrain, or through an event in your life that does the same and leaves you naked to ‘what is’. The analog axis cannot come into existence until the self is felt as a whole: once we have swept away the shadows of our neglect—its lethargies, its dullness, its anxieties—we can replace them with the sensitivity of stillness. It is into that stillness, then, that the waveforms of the present are received—as the stillness of a pond will receive the merest breeze floating over its face. When the body is grounded in stillness, the analog axis can open us to an exchange with we know not what intelligence it is that breathes through all things. And that intelligence can guide us as surely as a mother’s loving touch will guide her child.

Once the impression of that loving touch passes into the body, more subtly than any idea, you will discover that all of nature is your primer. Give the attention of your entire being to a tree, or a river, or the night sky, open your love to the present, allow it to touch your core, and its guidance will be felt vividly. Your analog axis joins you to the present by welcoming its energy. The subtlety of nature’s lessons can be equal only to the stillness to which you abandon yourself, but they begin simply enough.

The trees teach us how to stand.

The sea teaches us how to breathe.

The flower teaches us how to open our hearts.

The waterfall teaches us how to ground ourselves.

The mountain teaches us how to rest.

The river teaches us to move on.

The moon teaches us calm reflection.

The spider’s thread teaches us sensitivity.

The starry night teaches us companionship.

The blue sky teaches us patience.

Our culture assures us that anything we do has to be overseen by our enclosed intelligence and chaperoned by our willfulness. But the medium of the world in which we live is thought, as a fish lives in water. To open the second axis of our consciousness is to open to that medium, in all its vibratory stillness. Because the harmony of the felt present occurs within the spaciousness of a field that knows no boundaries, opening to that field requires a commensurate spaciousness: a sensitivity on which you yourself have placed no boundaries. And so it is that as the mind’s sensitivity opens through the widening spheres of its awareness, the chatter of the nagging, bullying inner judge falls silent, replaced by an immersion in the experience of the present: the caress of its waveforms speaks to the heart with intimate eloquence. That experience will make it clear to you as no other: the alternative to judgment, the antidote, is sensitivity. Judgment contracts the world; sensitivity dilates it into the truth and immediacy of the fluid present.

Our understanding that “all of nature is a great wave phenomenon” tells us that all of reality is essentially fluid. In the shift from ‘known self’ to felt self, we leave a frozen realm of division and fixity and enter the essential fluidity of ‘what is’. Mysticism and science give us different ways of understanding that fluidity; a remarkable book by Theodor Schwenk, Sensitive Chaos, blends those views to present a compelling vision of it. In the book he shows how our organs and bones and the bark of trees and river deltas and a multitude of other forms all testify to the flow that gave them shape and continues to shape them. Fluidity embodies information and facilitates exchanges, whether in the world around us or within. Physician and author Larry Dossey refers to the endless give and take of atoms that sustains all life as the “biodance,” which he describes as follows:

Biodance—the endless exchange of the elements of living things with the earth itself—proceeds silently, giving us no hint that it is happening. It is a dervish dance, animated and purposeful and disciplined; and it is a dance in which every living organism participates. These observations simply defy any definition of a static and fixed body. Even our genes, our claim to biologic individuality, constantly dissolve and are renewed. We are in a persistent equilibrium with the earth.200

As for the self, Alan Watts provided us with a metaphor that radically underscores the fluidity of our continuous exchanges with the world: “Man as an organism is to the world outside like a whirlpool is to a river: man and world are a single natural process.”201 He explained,

When I watch a whirlpool in a stream, here’s the stream plowing along, and there’s always a whirlpool like the one at Niagara. But that whirlpool never, never really holds any water. The water is all the time rushing through it.… And so, in just precisely that way, every one of us is a whirlpool in the tide of existence, where every cell in our body, every molecule, every atom is in constant flux, and nothing can be pinned down.202

The intelligence of the felt self resides in our fluidity and is processed through the exchanges along our embodied axis; but ultimately, too, the intelligence of the felt self resides within the fluidity of the great wave phenomenon of the present, and is processed through the exchanges along our analog axis. In fact, we could liken its intelligence to a womb in that it receives the world and integrates it and thereby births the self anew in each moment. We might even call that its first and foremost function: to receive the world’s coursing harmony that it might discover the reality of its own. That ability is its genius. And it is, to be sure, a physical genius, one that is guided by the subtle thinking of the world. We might think of that bodily intelligence, in fact, as the womb in which the Tao or the Logos is received and conceived. Oneness cannot be found, Logos cannot be heard, the Tao cannot be felt, unless the two axes of consciousness that constitute the genius of the felt self are sensationally processing ‘what is’ as a whole. In recognition of its genius for “feeling the thing as a whole,” we might name the united functioning of those two axes of our consciousness the logosmind—the mind that receives and conceives “the thought that steers all things through all things,” the mind that vibrates to the harmony of the whole, the intelligence that becomes whole through the whole.

The logosmind, then, is the thinking of the felt self. It enters the experience of the felt present just as you might ease into a hot bath, releasing every cell to the warmth of the water and yielding to the luxury of its sensations. It is a self-achieved abandonment in which you offer yourself completely and with gladness to the world around you, sensationally merging with it. The thinking of the logosmind thrives in the inner corridor and is liberated when it unites with the pole of the swirling present. Analytical thinking can play along the corridor and inform being and be informed by it—but the thinking of the logosmind does not rely on duplicates and is not predominantly analytical. But if it is not analytical, what is it?

Analysis is the separation of a whole into its component parts, and comes from a Greek word that means “loosening”—similar to the root of solution, which, as we saw, comes from a Latin word that means “to loosen.” And indeed, when you want a solution, analysis is likely to facilitate it. Like Alexander’s sword, it cuts the world into parts that retain no vestige of the perplexity that belongs to the whole; the divisions of analysis allow you to ponder the qualities and relationships of those parts. We commonly think of synthesis as the counterpart to analysis—and for good reason, because it means, as its Greek roots indicate, “a putting together.” But that is not how the intelligence that feels the world works: the world is together; it doesn’t need to be put together. Its togetherness is, in fact, immutable, indissoluble and inescapable, evincing a depth of interrelationships that we cannot begin to compass. If we tried to put the world together, we would undoubtedly end up with a synthetic duplicate. Patently, another word is needed, one that suggests the unity by which the logosmind feels the world in itself and its self in the world.

The word assimilate suggests both of those aspects. The OED lists two related meanings for the word: “to make or be like” and “to absorb and incorporate.” The word is related to other English words such as similar, same, ensemble, simple and single, and all of them trace back to an Indo-European base, sem-, which means “one, together.” The word assimilate aptly describes the thinking of physical genius: Gretzky stepped onto the ice and assimilated what was happening there in its entirety; Charlie Wilson looked at an aneurysm and assimilated it; and that’s precisely what the old woman was urging the young Noh actor to do: not synthesize his facts into a performance, but assimilate the role—feel it from the inside and embody it, as the stylus of a turntable yields to and reveals the waveform of the orchestra. Of course, the ultimate affinity towards which the logosmind is drawn is an assimilation of the One Presence. To honor that natural affinity is to find yourself in the presence of the One Mind even as you find it within you. Assimilate this, let this assimilate you: that is the heroic surrender.

Understanding that the logosmind thinks predominantly by assimilation suggests the fluidity and openness of a mind in which all things are allowed to come into relationship with all things. It also provides us with a means of calling ourselves to account. When you stand and converse with someone, do you assimilate the present, or switch out of it into the kind of role-playing expected of you by your relationship with that person? What might happen if, while conversing, you allowed yourself to assimilate the present—just as the hero journeys into unknown Being? When you walk down the street, can you assimilate the present? Or while in the grocery store? Or while eating a meal? As soon as you can answer “yes” to such questions, you have activated the thinking of the logosmind, which will illuminate the whole of your life with a newness and truth that reveal the realm of the felt self.

We can further call ourselves to account once we understand that the rigidities of the hetabrain are organized to secure results and the fluidity of the logosmind is an attunement to process. The differences between process and results are familiar enough to most of us; but those words take on a new significance when we scratch them to look at their roots: process comes to us from the Latin procedere, “to go forward, advance,” and result from the Latin resultare, “to leap back, spring back, rebound.” Process, which is always about assimilation, carries us forward into the felt perplexity of the present; a concern with results, or doing, pulls us back into the familiar duplicates of the ‘known self’.

Consider this: we seek, expect and even demand convenience in our lives. We feel entitled to it. Convenience, of course, is nothing other than the ease of getting results. But it would follow then that the more convenience we enjoy, the more we disconnect from process—and, by extension, the more we disconnect from Being. We tend to take for granted those things on which the convenience of our daily living depends, and feel no obligation to honor the complex and sophisticated processes that sustain them. As Jean Houston observed,

Most of our ancestors knew process all the time. They planted the seed, they chased away the birds, they nourished the plant, they baked the bread. We just stand in the supermarket line. Maybe much of our social pathology is a lack of process—we have no sense of the moral flow of things.203

A similar observation was made by science activist David Suzuki: “We live in a shattered world.… It used to be that everything you did carried certain responsibilities.”204 When we accede to convenience, we undermine relationships and our own ability to assimilate reality. Are you on a first-name basis with your bank manager? I don’t even have one—I use a virtual bank with ATMs. As a kid I knew the milkman, the fruit and vegetable man, and the butcher—who once told me that to get the sawdust for their floor they had George in the basement with a handsaw, cutting up boards all day. In the summers we occasionally bought produce directly from a farmer, who lived in a different rhythm and always had time to chitchat. These days the chicken for sale in our brightly lit supermarkets comes from birds that have suffered an inhumane existence, shelved in a factory like a mere commodity and as rigidly hidden from the light of day as the hetabrain’s ideas are from the Logos. Fruits and vegetables have been irrigated with aquifer-depleting waters, doused with chemicals and flown or trucked thousands of miles. I find there are certain ‘normalized’ conveniences I can no longer assent to—the personal cost of dissociation is too great.

As our addiction to results and convenience diminishes our relationships with the world, it bolsters the amnesia of our abstractions on every scale, so that we forget to feel; but our patterns of thought and behavior don’t need feeling: they drive themselves, fixated on results. Deafened to the ways in which the world calls out to us, we obsess over our personal agendas. And those often concern the problems of money, because money represents an entitlement to sidestep process and demand convenience. The dreams of the hetabrain, built on its scaffolding of duplicates, occupy us relentlessly, even as the womblike ability of the logosmind to receive ‘what is’ and process it is numbed with neglect.

I have a confession to make. I was out for a long run on a bright spring day, trying to feel my way with every available faculty towards a metaphor by which the intelligence of the felt self could be understood, when the image of the womb came to mind. I was under a large willow tree on the edge of a trout pond and I stopped in my tracks, letting the metaphor settle into and through me. And a part of me flinched. A part that, despite my understanding about male doing and female Being and self-tyranny and heroic submission and all of that, still flinched at the prospect of identifying so closely with the female element. On the one hand, standing stock-still under the shifting sky it was so clear to me—I am a womb; more specifically, the intelligence I experience through my body, unlike the enclosed knowing of the hetabrain, can only be fully honored and fully realized when, like a womb, it is allowed to receive the world into its emptiness; when its genius is free to work in ways I cannot understand or control, but can feel; and when I wholly attend to the guidance of the whole as it is born within me. On the other hand, a product of my culture, I flinched. It passed, easily enough. But I will never forget that it happened.

We have suggested the whirlpool as a metaphor for the logosmind, wherein the fluidity of the self attunes to and reveals the currents of the world. As for the barricaded hetabrain, I can’t think of a better symbol than Professor Pippy P. Poopypants. The Professor is a character from the brazen comic book series by Dav Pilkey, The Adventures of Captain Underpants—a scientific genius who, having been stung by mockery and humiliation, decides to take over the world. Obsessed with renaming everyone on the planet, he creates a man-shaped robot ten stories high with a glass-domed control room for a head. Standing in that head he can watch the world outside, assess it from that perspective, and impose his will upon it by operating the robot.

Amidst its playfulness and comic-book zest, Professor Poopypants, housed within his robot, is the archetype of the hetabrain in action. He is a tyrant of self-achieved independence who ensconces himself in the head of a mechanical creation of his own making and pursues an agenda of such acquisitiveness it would mean the destruction of the world. Being a male Professor, he not only represents the element of doing, he is cast as an authoritative patriarch. Confident in his own superior intelligence, he excels at manipulating abstract concepts, which he does from the headquarters of his robot body, busy with the cybernetics of controlling it, obsessed with his agenda of names/labels/symbols and what he must do to carry it out, all the while buffered from the sensational processes of the world, which he monitors through the robot’s domed window.

As the image of Professor Poopypants illustrates so clearly, the hetabrain inhabits a headquarters of its own making, one that renders the body as a mechanism and the world as exploitable. By contrast, the logosmind lives with the world as its complement: its willing passivity to ‘what is’ enables it to enter a mutual awareness with a felt whole. Whereas the hetabrain contracts into the consciousness of tyranny, the logosmind rests in the consciousness of being. Other differences between the hetabrain and the logosmind might be compared as follows:

The Universal Law of Interrelationship is the strength on which the logosmind builds; the illusion of perseity is the foundational premise of the hetabrain. It is also the premise of our culture. Of course, our adherence to four dimensions will never turn perseity into a real phenomenon. We can consolidate the known and avert our gaze from fluid mystery; we can obsess over our duplicates and neglect the living guidance of the moment; we can seek refuge in the smaller self and disconnect from the larger Self; in short, we can refuse in any number of ways to open ourselves to the full dimensionality of the world; but we cannot create perseity. Not in physics, genetics, art, meaning, self, careers, families, human behavior, nations or nature. As physicist Lee Smolin reminds us, the world is

a vast, interconnected system of relations, in which even the properties of a single elementary particle or the identity of a point in space requires and reflects the whole rest of the universe.205

His observation raises a question that is particularly pertinent to an understanding of ourselves: if there is no perseity, what is the nature of our thinking? Does a single thought “require and reflect the whole rest of the universe”? Or are all our personal thoughts created within the seclusion of our craniums, independent of the universal flux? Is our thinking somehow an exception to the Universal Law of Interrelationship? Should we draft up an exemption for ourselves? The hetabrain views thought according to the computer model: an enclosed rationality that looks at the world as though from behind the screen of its monitor. The ideal of pure rationality epitomizes the characteristics of perseity, being associated with self-enclosure, autonomy, authority and the right to rule. Fictions all, but they communicate such a seductive story that Darwin himself was prompted to write, “Of all the faculties of the human mind, it will, I presume, be admitted that Reason stands at the summit.”206 That summit, of course, is the prospect that provides us with objective perspective. But detached reason—divided from the world by the very altitude it seeks, determined to elevate itself above the messiness of feeling—cannot assimilate. Its digital duplicates cannot ‘yield to what is’—the basis of physical genius. Its judicative perspectives, however thickly piled one on top of the other, cannot create a whole. In this context, Rachel Carson’s suggestion, “It is not half so important to know as to feel,”207 acquires a particular poignancy, and provides a stark contrast to Darwin’s.

We sometimes mistakenly imagine that thinking is synonymous with reasoning. As we have observed, though, thinking is necessary to catch a ball or ride a bike, and such thinking is not reason; it is sensational thinking, the thinking by which physical genius is able to process the whole and respond out of wholeness directly, without a need for mediation. Sensational thinking guides the aerialist aloft on his tightrope, and the mother’s love for her child, and the limitless understanding that that love bestows. It guides our understanding of Bach or Rembrandt. Sensational thinking is what alerts the ‘self’ aspect of consciousness to the ‘world’ aspect of consciousness and brings those two complementary poles into mutual awareness. It is through their interplay that our consciousness derives new harmonies and new insights. Yet the hetabrain has the nerve to declare reason to be the supreme faculty—and then it adds insult to injury when it dismisses the thinking of the logosmind as irrational. When we remember that the root of rational is found in a word meaning “to join,” the description seems downright ironic. The hetabrain, working in the splendid isolation of its own abstract concepts, is the truly ‘disjointed’ faculty.

But it is easy enough to understand how the hetabrain came to think of the logosmind as irrational: the analog axis of the logosmind functions in fluid partnership with the world; it can no more think by itself than one leg can walk without the other. Now imagine that you overheard someone alone in the next room talking on the phone, and that you didn’t know such things as telephones existed. Hearing only his side of the conversation, you would think him mad, or irrational. That is precisely the case with the hetabrain: when the logosmind is thinking hand in hand with the Living Logos, the walled-in hetabrain overhears half of the conversation and, alarmed, proclaims the logosmind to be irrational. As a popular saying frames it, “And those who were seen dancing were thought to be insane by those who could not hear the music.”

In much the same way, we may be inclined to think that the shamans and oracles of the world are off their rockers. Actor David Niven wrote of an incident in which he and his wife were staying with friends in the country. A hunt had been organized, but when it was time to leave for it, David found his wife reading a book. She calmly explained to him that she wasn’t coming. He asked why, and she replied that if she did come, she would be shot. He was disappointed by her decision, reasoned with her that it was quite irrational, and implored her to change her mind. She finally relented, saying, “All right, but I’m going to be shot.”208 And so she was, in a freak accident that nearly left her disfigured.

All of us have probably had, or know someone who has had, such direct, ‘irrational’ insights. My friend Jack saved his mother’s life by heeding what he ‘irrationally’ knew, leaving his classroom to run home. When my wife was a teenager she was driving down a winding mountain road into the setting sun when the car ahead of her, which had no brake lights, suddenly stopped. She hit the brakes hard, and her car skidded to a stop, narrowly avoiding a collision. When she got home, her mom asked her anxiously, “Are you all right?” About twenty minutes earlier, at the time of the near collision, she had had a terrible feeling of impending danger for her daughter.

The description of the logosmind as irrational has been foisted upon us by the hetabrain and helps to keep us in its thrall. It’s time to free ourselves from that deceit. After all, who would ever trust themselves to a faculty that they truly believed was irrational? It would be … well, irrational. But the thinking of the felt self isn’t irrational, it is corational—literally “joined together”; and the mystery, the begetter of the interweaving perplexities around which we gather ourselves, the hidden harmony of things, the Logos, is its unseen partner in thinking—specifically, in sensational thinking. The logosmind is bestirred in a give-and-take with the currents of the great wave phenomenon around us, and from that wordless, sensational interplay the felt self is gifted with insights that emerge from Being itself. And so it is that the analog axis of our consciousness converts sensations into insights: insights that tell you, for example, that you will be shot if you go hunting today; that as you sit in class, your mother is dying; that your daughter is in danger; or even, if you attend patiently and sensitively and devotedly enough, that E = mc2. Einstein wrote of the act of discovery, remember, that

The intellect has little to do on the road to discovery. There comes a leap in consciousness, call it intuition or what you will, the solution comes to you and you don’t know how or why.209

As Heidegger suggested, “essential thinking is an event of Being.”210 When the self aspect of consciousness unites with the world aspect of consciousness, the thinking self recognizes its identity as the felt whole, and its insights arise from Being itself. Sensational genius, then, is not something you possess—it is a property of the dance of opposites in which you stand; and the more sensitively you awaken to that dance and yield to it and participate in it, the more fully you enable that genius. You also begin to realize that certain anecdotes that we normally make palatable with a grain of salt, or consider to be quaint or metaphorical, are actually saying exactly and literally what is intended. Einstein was not being allegorical, but merely accurate, when he wrote that the harmony of natural law “reveals an intelligence of such superiority that, in comparison with it, all the systematic thinking of human beings is an utterly insignificant reflection.”211 Morehei Uyeshiba, the founder of aikido, was also being factual rather than poetic when he commented that

the secret of Aikido is to harmonize ourselves with the movement of the universe and bring ourselves into accord with the universe itself.… When an enemy tries to fight with me, the universe itself, he has to break the harmony of the universe. Hence, at the moment he has the mind to fight with me, he is already defeated.212

When Heraclitus wrote, “Listening not to me but to the Logos, it is wise to acknowledge that all things are one,”213 he didn’t feign listening—the Logos was his real, unseen partner in corational thinking, just as the harmony of the universe was for Uyeshiba. To feel “the harmony of the universe” is to feel the coherence of the transforming whole advising us, ushering perspective into sensation and sensation into insight. The immediacy of such an experience is beyond all ‘rational’ understanding, beyond reason, but also beyond doubt: baffling and frustrating to the hetabrain, it is recognized as direct, primary, relational truth by the logosmind. On his return trip from the moon with the Apollo 14 mission, Edgar Mitchell looked out the window at Earth floating in the vastness of space and received a life-shaking insight about the hidden harmony of things and the palpable presence of divinity. As he later explained, “The knowledge came to me directly.”214

It should be clear by now that the thinking of the felt self does not disdain the analytic aspect of our male consciousness; rather, it brings that faculty into relationship with the pelvic intelligence, where perceptions interact with a host of sensitivities that locate them in the present. That interaction is transformative: once an insight comes out of isolation and joins the present, it is experienced sensationally, and will be sensationally informed by the present. That conversion of a discrete perspective into sensation is analogous to the way nuclear fission converts bound matter into energy. The energy that is released as sensation is ungovernable, and where it might carry you is unknown; for that reason, it is feared by the hetabrain.

In the symbolic language of myth, we might note that when a male perception forsakes all urges towards tyranny, it can venture in submission down the corridor to the chthonic realm of female being, to be made whole by joining the whole. That journey changes the perception, as we have said; what is more difficult for us to understand is that it also alters the present—which unfailingly shifts as the fusion of the perspective into being converts it into energy. The Global Consciousness Project lets us see that effect on a grand scale: for instance, as the ceremony of Princess Diana’s funeral converted the public consciousness of her death from a fact to an integrated, sensational understanding located in the present, random-event generators around the world registered the event: the shifting of the present.

The second form of conversion carried out by the thinking of the felt self—from sensation into insight—arises from a deeper partnership with the present. As our sensational union with the world shifts our spiritual center of gravity into the dark beyond, it often draws our attention to a potential source of grace; if we attend to that shapeless, sensed phenomenon before us, we become increasingly sensitized to it. Suspended in the dark emptiness between the poles of self and world, it acquires more and more presence, until finally it is released into the light of consciousness as a full-fledged insight. The liberation of such insights is also liberating: they are so deeply integrated, and so sensationally informed, that they accord with and reveal the whole from which they arise. They can take the form of a deep truth that speaks to your own life, or a line of poetry, or the revelation of a scientific principle: E = mc2, for instance. Once such a gift of insight arrives, it triggers the energies of the felt self in a profound, sometimes soul-shaking wash of sensations; and those sensations in turn, once integrated, provoke further insights, so that the dance between the male and female aspects of our consciousness carries us deeper and deeper into the subtle sensitivities of the mindful present. That, then, is the true nature of our corational thinking—and I have come to trust it deeply, for there is no other means by which I could have written this book.

It turns out, then, that the analog axis of our consciousness is actually more than a means of receiving the waveforms of the world, in the way that a stylus receives the waveforms of an LP. Like the embodied axis, it enables an interplay between its poles in both directions. Through the analog axis, we not only receive the world: we behold it and are beheld. It is the axis by which the self aspect of consciousness and the world aspect of consciousness join in mutual awareness. It is along the analog axis that the sphere of our sensitivity opens to the corational nature of consciousness. An apt metaphor for the analog axis was expressed by Hiroyuki Aoki, the founder of Shintaido—a martial art founded on and shaped by its expressly spiritual concerns. In speaking of our duty as humans, Aoki said,

The unconscious soul of the universe with which we are unified is completely reflected in the heart of great Nature.… And because we are such a small part of the natural world, it is good to imagine that there is a large pipeline connecting everything—earth, self and solar system—and that it is our task to clean and enlarge it.215

The trinity of “earth, self and solar system” evokes the mythical axis mundi that unites earth, man and sky—and it reflects the inner trinity of pelvic bowl, heart and cranial brain. And just as the embodied axis of that inner trinity is supported by a corridor that grows more spacious within us as we grow more sensitive, the analog axis of our consciousness is supported by “a large pipeline connecting everything”—a pipeline that we might refer to as the corational corridor. Our task is to “clean and enlarge it,” as Aoki says, so that as its spaciousness grows, our sensitivity grows, until finally all the world around us is seen to be a vast, corational corridor, revealing “the unconscious soul of the universe with which we are unified.”

Our corational partnership with the “unconscious soul of the universe” forms the basis of what I consider to be among the most transformative of prayers: “Thy will be done.” To the casual observer, the prayer might seem ridiculous or even arrogant: that an individual should think that she can request of God that He enact His own will, or somehow give her permission for Him to do so—as if she had any say in the matter. In fact, the prayer is a profound expression of self-achieved submission, an abnegation of will and an awakening to the hidden coherence of all that is. It is transformative of self and world—inextricably linked as they are—precisely because it brings you into accord with that limitless harmony; it is empowering because it relinquishes force and the fiction that drives it, and celebrates the great dance of renewal and the sensitivity that enables us to feel it. Only by submitting to what is can you feel what is. And so we might come to understand that those whom Gladwell called physical geniuses might also be called geniuses of corational thinking—geniuses for being able to devote their attention to a challenge to which they have been called, and to “feel what is” in its living reality. We help the world not with willpower, but with sensitivity.

A key to the thinking of the felt self is found in an early Buddhist text that observed, “When the mind is disturbed, the multiplicity of things is produced; but when the mind is quieted, the multiplicity of things disappears.”216 The multiplicity of things arises from a mind attached to the fiction of four dimensions, which presents a world made up of innumerable independent objects. The imagined autonomy of those objects provides the central conceit of control on which the hetabrain depends, for mastery is possible only over the bits and pieces of a world that is artificially broken up—like the Gordian knot sliced apart by Alexander’s sword. Similarly, mastery is possible only over the bits and pieces of a self that is artificially broken up. When the harmony of Being is broken, Authority takes over, chattering away in its incessant, distracted monologue, obsessed with systemizing the world’s multiplicity.

The thinking of the felt self, then, is grounded in stillness, which reveals the world as a unity. If we cling to the idea that our intelligence is our own personal computer, plugged into our brain stem, shielded from interference by the blood-brain barrier and ready to calculate solutions to our problems, we forget stillness and trust in the application of force. If we understand that our true genius is found in our capacity to clean and enlarge the pipeline, heeding the all-informing companionship of the present, we will trust in the felt mystery and the calm sensitivity in us that accords with its guidance. That is the state of a corational genius who, like an accomplished surfer, rides the unfolding wave of the present without fear or consolidation; the rest of us are too busy looking for ways to exert control over the board and the self to really feel the wave—the Logos—that carries us.

We might finally note that when love roots the felt self in the stillness of the present, its vibratory calm reveals, above all, that you are not alone: you breathe with all things as they breathe with you, sensitized to the grace of mutual awareness. To look upon the world, immersed in its wild peace, is to know that you are known. The union between love and corationality is made memorably clear in a story that was told to Matthew Fox by a car mechanic. As Fox tells it, the mechanic

was depressed at work but stuck with his job because of family responsibilities. Then he encountered a Sufi teacher who said to him, “Each time you turn the ratchet as you repair a vehicle, speak the word Allah.” The mechanic did so, and his whole life changed, the whole relation with his work changed. “Now,” he said, “I love my work. I love cars. They are alive. It is a mistake to think of animate versus inanimate. A car will tell you, if you listen deeply enough, whether it wants to be repaired or whether it wants simply to be left alone to die.”217

By the same token, I have found it immensely helpful to recognize that any time you feel alone in doing something, it is a sure sign that you have detached from the present, abandoned your own wholeness, and entrusted yourself to the unipolar realm of doing and willpower. What pulls you into that realm is easily identified: by detaching from the present, you render the world four-dimensional, whereupon the corational corridor blinks out of existence, like Eurydice; and then you have nowhere else to stand but in that realm. In fact, it becomes clear that just as a collapse of the inner corridor creates a unipolar consciousness, a collapse of the corational corridor creates a unipolar existence: in the absence of the corational corridor, you become trapped in the self—watching the world as though through a window, fundamentally desensitized to it. Of course, we are all directed into a unipolar existence by our culture’s story. What other fulfillment could our belief in perseity provide us? It denies the call, refutes the relationships that constitute Being, sanctions self-absorption, and dismisses any notion that our spiritual center of gravity might lie in the felt unknown beyond the self. We feel that by accepting our culture’s staunch axioms we are keeping to reality—but as we have seen, reality is a union of opposites that dance the world into being. Only when we open to that dance—to the diversity, energy, newness, calm and harmony that thrive between its vibrant poles—can we feel the dance and join in. And there is literally a world of difference between standing in a unipolar realm and dancing through the energized expanse that is held between complementary opposites. It is only in the spacious companionship of that dance that we can “feel the thing as a whole,” and find our peace in it.

Finding peace while holding a mechanic’s wrench or in the midst of our commonplace chores and activities is not always easy—and there are no shortcuts to it. Peace is not a matter of stress management; it is more than the absence of anxiety. Peace is a full acceptance of the whole of your life and an engagement with the whole of your truth; it is what opens you to the transforming present. Any parts of you that are chronically not at peace—any parts that carry judgment or plans or resentments—cannot be made to conform to peace, or go quiet: they live in the body and have to be processed by its fluid intelligence. You cannot join the present until you offer your entire body to the present—so that the felt self can come to rest in the pelvic bowl, quickened to the subtle stirrings all around it.

When the poet A. E. Housman was asked to define poetry, he famously replied that he “could no more define poetry than a terrier can define a rat”;218 but he added that he thought both he and the terrier recognized their quarry by the physical symptoms it provoked in them. Like the terrier hunting a rat, an artist pursues the resonant life of his artwork with gestures or syllables or daubs of paint or notes of music; and like the terrier, the artist is guided in his pursuit by the physical aliveness of his response, which tells him it’s the real thing. When the artist eventually stands back and declares the artwork to be complete, it is not because he has achieved something fixed, solid and eternal, but just the opposite: the artist knows his work is complete when it has acquired such sensitivity that each part is fluidly responsive to every other, so that as he looks at the whole of it, it won’t hold still, but moves with the subtle slipperiness of a living perplexity.

The same truth obtains for us with regards to the body: just as an artwork is fully realized only when it achieves consummate fluidity, it helps to recognize that you are fully present to the world only when your body is completely unlocked to the currents of the present. Only movement can know movement, as the whirlpool knows the river. That is the aim of the best bodywork: to awaken the body into a state of awareness and flow, freely responsive to the perplexity of ‘what is’, so that the wave of each breath ripples through the body as a whole and the whole is experienced as a borderless field of energy attuned to the felt singularity of the present. Whenever the body yields to that kind of fluid harmony, the merest reverberation in the core of your being will ripple through the whole of it. As the world aspect of consciousness and the self aspect of consciousness come into relationship as complementary poles—each the beholder, each the beheld—the subtle, yielding, sensational, insight-birthing currents that run along the analog axis between them are literally a dialogue; and it is in that dialogue that you truly “feel the thing as a whole,” even as the whole is feeling you.

Just as our word analog traces back to the Greek concept of Logos, so does dialogue: it comes from dia and logos, which combine to mean literally “through the Logos”—and through the Logos is precisely how the felt self thinks: when the pole of the self recognizes its complement in the living present, and opens to it so that what is passing through the Logos passes through the corridor of your being, then your core will answer as a compass needle does to the far poles of the earth. And so the dialogue begins. All information is shared information.

“Feeling the thing as a whole,” then, is not a striking and grand accomplishment that is achieved by standing back and taking it all in from some überperspective; it occurs as you enter a living conversation with the whole—and that can only happen on a very subtle scale: a scale revealed by stillness. A surrender to Being is a surrender to its intimate dialogue. Be still, and know that life is subtle.

The subtlety of your relationship with the living present is revealed only to the degree that the subtlety of the body is brought into awareness. That awareness is not some rarefied abstract ideal; it is what you begin to feel when you grow fully passive to the mindful body and honor its merest sensation as being fully worthy of your attention. It is only on the scale of such subtlety that the body can be experienced as a vibratory medium, and the logosmind revealed. We have been advised to regard the subtle stirrings of the body’s energy as the unintended offspring of various biochemical processes of physiology, often nuisances at best and barely worth our attention: but they are much, much more than that. They are the stirrings of our unnamable and acutely sensitive attempts to assimilate the present and accord with it as a whole. The consciousness of the named ‘I’—your ‘known self’—resides in the hetabrain; but the consciousness of the ineffable felt self resides within the subtle stirrings of the body. If those subtle energies are in conflict, the ‘I’ is in conflict; if those energies are coherent, the ‘I’ exists as a whole and can come into relationship with the present as a whole.

Subtle energy does not lie. It is what it is. It is beyond the reach of any of fantasy’s coarse fabrications. As the sphere of our sensitivity dilates to take in more and more of the world, it is specifically opening more and more to the world’s subtlety. Once you start to lift the curtain on that humming universe, you will find that the subtle energy of Being suffuses everything: it illuminates the teacup, and answers your heart’s gaze; it sifts between the pine needles, and seeps through them, even as it sifts and seeps through you. The subtle currents of the world strengthen the mechanic’s wrench as he speaks “Allah” and guides it with grace and companionship.

There is a poem by Bashō that was written while he was traveling The Narrow Road to the Deep North: his house sold, his heart “filled with a strong desire to wander,” he was well into his journey, being led along a path on horseback, when he addressed the farmer leading him:

Turn the head of your horse

Sideways across the field,

To let me hear

The cry of a cuckoo.219

The horse, like the part of us that persists in doing, is brought to a stillness; and off to the side, across the field, comes the quiet, bright song of the present: the Self calling to the self.

The thinking of the felt self, as we have seen, begins along the embodied axis: once that axis unites cranial brain and pelvic intelligence, the self can be felt as a unity; and then the analog axis can bring the self aspect of consciousness and the world aspect of consciousness into mutual awareness. The union of those two axes is what we might call the crux of our consciousness. That much is clear, but that clarity raises a larger issue: if we have a purpose in our lives, individually as well as collectively, surely the capacities with which we were born and from whose interplay our very natures are forged would give us the most direct indication possible as to what our purpose might be.

It is clear that our first task as humans is to unite the poles of consciousness within us; and, indeed, the task of joining male and female in full, embodied consciousness gives most of us fodder enough for a lifetime’s work. But let us suppose that we learn to still the fears of the tyrant and to open our hearts to the fragile beauty of the world around us. Let us say that we finally come to see that the only way to bring male and female into balance is to say, “First, being”; and that the driven, anxious, dissociated male grows passive enough to all the subtle currents and energies of Being to feel them and fall in love with them and fall into them. And suppose that in that spirit of adoration our male perspective surrenders its strength to the all-integrating genius of Being, and the two are united—and that their unified sensitivities then open to find their complement in the singularity of the felt present. What then? What does that newborn mutual awareness enable? What does it prepare us for? Through what work could it fulfill itself?

The sensitivity of the felt self enables us to venture into the mountains and valleys of the human enterprise all around us, into the mysteries of great nature, and gain perspectives of utter clarity on our world, and integrate those perspectives so that they deeply enrich our ability to see and understand the world—and, living in that renewed seeing and understanding, to feel more clearly our relationships with ‘the thing as a whole’, attending to it so closely that sensation converts into perspective, illuminating the felt mystery of the Logos. The effect of such a venture is to sensitize us to all the relationships that constitute our being; and that, in turn, sensitizes us to the One. As we find ourselves more and more deeply reflected in the world around us, not only will our responses to the world bring our core into full relationship with it—they will bring our core into its full and irrevocable responsibility to the world. It is in that awakening to responsibility that our strengths find their purpose and that we are carried into the grace and poignancy and power of our own lives. It is in the illuminated, ordinary relationships of that responsibility that we find our presence, our true freedom, and our limitless creativity. It is through the actions into which that responsibility carries us, and with which it challenges us, that we will undertake a personal journey of discovery that will not just bring us into harmony with the world—it will enable us to actively deepen that harmony.

And so it is that the heart, dynamically awakened by the energy of the embodied axis within us, opens to discover its self in the world around it, and to recognize that self as the One—and to be carried by its intimate love of the One, its love of life itself, into the revelatory, activated gifts of sacred responsibility. That is the single purpose to which our true nature is born. It is the journey the world asks you to take, and it is on that journey that the world will most profoundly bless the days of your life. The world is inviting you on that journey right now—if only you could hear its invitation all around you.

The crux of your consciousness lies in the meeting place of self and world. It is there that the embodied axis engages in interplay with its complementary pole in the embodied world, activating the corational axis. Naming and even feeling that crux is one thing; finding a way to center yourself in its coursing intelligence is another. We have looked at the whirlpool as a metaphor to help us feel and understand the logosmind. This exercise helps us feel and understand the felt self.

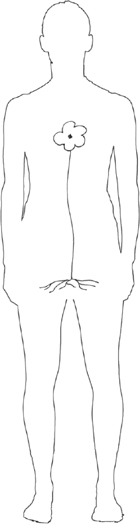

The dynamic of the felt self, as we have said, is one in which you rest in the pelvis and act from the heart. It finds its complement in the dynamic of a simple flower: its roots are sunk deep in the stillness of the dark earth, and its many-petaled blossom, like the heart, opens to the world. That dynamic heightens our affinity for flowers, since it also stirs deep within us. To connect with it, begin by standing upright, knees soft and hips floating, and allow the breath to drop into the pelvic bowl and release out. In this relaxed state, allow the elevator to drop down the shaft (see Exercise Six) and come to rest on the pelvic floor. Once your sensitivity has gathered in the pelvic bowl, feel the roots of the flower securely and deeply grounded there, and feel its stem carrying the vibrational energy of your being from those roots up to your heart, which blossoms within your breast and shares that energy with all the world.

As you feel the roots, stem and blossom acquire presence and specificity within you, you might note how your sensitivity attunes to the world differently. You might also be aware of a tendency to focus on the blossom—just as we forget the roots when we cut flowers and arrange them in a vase. It is from the roots, though, that the flower draws its life-sustaining nourishment. If you put your attention on the roots, allowing them to ground themselves in your pelvic intelligence, you may also feel them rooting themselves in the present; and then you can understand that it is not any energy you possess, but the energy of the present itself, that streams up from the roots and opens the heart to the world—an opening that is connected to and expressive of the pelvic bowl of being, in which male and female unite.

We have spoken of the energy of Being as a vibrational energy—the great wave phenomenon. Like the Tao, that energy cannot be lost, but it can be found. When the vibrational present touches your core and lives there, the stem that carries its rooted energy through the heart and into the world might be experienced almost as a cello string—vibrating along its length within you, between pelvic bowl and heart, singing to the world and with the world. Without that living correspondence between the pelvic center of your being and its love-supported portal to the world, your soul’s energy will be at a loss to greet the world and join it. Similarly, if the portal of your heart is open to the world, but not rooted in the depths of your being, it will disconnect from your place of rest.

The vibrational flower of the felt self is a guiding image I return to frequently, and it is a practice that all the other exercises in the book are designed to support. Once you have activated that image within you, though, allow it to disappear. Like any other exercise or metaphor or system of understanding presented in this book, if the flower is taken to be a solution, it will stand between you and the world as surely as any duplicate. The image is useful only to the extent that it opens a door and newly sensitizes you to ‘what is’. So let go of the image, and step through the door it reveals. If roots, stem and blossom were all clearly felt as a unity within you, then where the flower was you will likely find, lingering within you, the awakened, dynamic crux of your consciousness, sensitized to the corational corridor all around you. A direct experience of the great wave phenomenon of being, and of you as an indivisible part of it, will itself begin to heal the deepest schisms we live with: the rupture between our thinking and our being; the disconnect between our pelvic intelligence and our hearts; and the artificial divide of self from world.

Those schisms, incidentally, show up for all to see in what our culture accepts as normal adult posture. If you look around at people as they stand or sit or walk, you will notice that the angle between the neck and the upper back is an obtuse angle—that is, it falls somewhere between 180 and 90 degrees. The angle tends to get smaller with age; in some people it can even approach a right angle. If our torsos were erect, that angle between neck and torso would leave us all looking at the sky (Figure A); but our chests have so collapsed upon our hearts that we are actually looking forward (Figure B). In our culture, the chest tends to progressively collapse as we age, so that we have to lift the head more and more to continue seeing in front of us.

Fig. A

Our culture’s ‘normalized’ collapse of the chest cannot be wholly explained by aging, or the effects of gravity, or osteoporosis; it is a direct result of our unipolar existence, which dissociates from the present, and our unipolar consciousness, which dissociates from the body. As a result, the energy of the heart is unsupported by the energy of our being. When the energy of the heart flags, the chest sags, and the tilt of the head adjusts to compensate.

Fig. B

Fig. C

There are many exercises and techniques for improving our posture and our biomechanics. I suggest that the ones that really work are those that help us, inadvertently or not, to open our hearts and ground them in the energy of our being. The flower of the felt self takes the direct approach: it connects the heart’s energy with the vibratory energy of our pelvic intelligence, which opens the heart to the living energy of the present and supports us in all we do. When the crux of our consciousness is awakened like that (Figure C), the body’s energy follows: the angle at the back of the neck becomes a gentle, elongated convex curve, and we stand up straight—not because it is the ‘correct’ posture, and we ‘should’ stand that way; not because we need to house an inflated ego; but because, by surrendering to the energy of the present, we open to it and celebrate it.

There is a remarkable time-lapse video of a lily blossom opening that perfectly coveys the affinity between the opening of a flower and the opening of the heart. I could watch it once a day. It can be viewed at http://www.seantamblyn.com/island/Last%20Day%20Lily_100.swf