Let me tell you a story. A tale of bread dipping, of ‘Kitchen Bread’ and how it changed my life forever. I was a skinny teenager growing up in a seaside town. I looked, as my games teacher once opined in those crueller times, like ‘a twitching, neurotic streak of piss’. When the time came to get a summer job, I lacked the self-confidence or the physical coordination to get past a trial shift as a waiter in a beach café, so I went for a kitchen job at Forte’s.

Forte’s was an institution in my town. The legendary British–Italian restaurant dynasty had a branch there and owned several monumental dining palaces. The one I was hired into was on the town square – a building containing a traditional tearoom with palms and napery, a more ‘modern’ cafeteria and an impossibly glamorous carvery and grill room. I believe this occupied the top floor – I know the waiters wore uniforms, anyway, because I remember them yelling at me – and I imagined the room was filled with local Rotarians and their wives quaffing claret. I never ate there… in fact, I never entered the room, because my entire contact with it was at the doors of the lift in the basement wash-up.

Forte’s had class – or, at the very least, a brilliant understanding of what the British holidaymaker thought was classy. Though it was serving an unconscionable quantity of egg and chips to people who ate out once a year, there were proper facilities, there were trained and respectful staff and there was a proper kitchen with a full brigade. There were senior chefs in tall hats, distant and imperious. Lower ranks were villainous creatures, often having gained their working experience doing National Service in the Army Catering Corps. Today, when every chef ’s CV must feature a mandatory ‘stage’ cleaning mushrooms at Noma, it’s difficult to imagine that their forebears ‘staged’ in British Malaya, making egg and chips as bullets whistled past. They were some of the most worn-out, depleted and vicious human beings I’d ever met and they scared the hell out of me.

Beneath them all, figuratively and literally, in a sub-basement, was me. All the washer-uppers were Italians. Older, rural guys, built low to the ground, covered in muscles and speaking absolutely no English. Their impression when the restaurant manager thrust me into the room, looking like Oscar Wilde’s weaker younger brother, in a nylon tunic and a paper hat, was mercifully obscured by the impenetrable barrier of language. I’m betting it wasn’t good.

The work was viscerally disgusting. The facilities and equipment were fine, the room ventilated and well-lit and the staff well-trained and efficient. But to a fifteen-year-old whose only experience so far had been helping mum with the dishes – once – it was beyond comprehension. Trolleys came in with swaying piles of plates and cups. Everything from cigarette butts to baby vomit had to be scraped off into a bin. A machine with a long tongue of a conveyor belt had to be fed, constantly. The noise was terrifying and every ten minutes a glass would explode.

We worked for hours and then, quite suddenly, there was a change of pace. The trolleys slowed and the other dish washers moved, unbidden, to other tasks. One began breaking up a delivery of long, crusty ‘French stick’ loaves. Another poured gallons of orange juice into the big chiller tank. One small man who looked like he knew a thing or two about working with livestock back home slammed cardboard cubes into The Cow (The Cow was a refrigerated cabinet with a tap on the front and each cube contained a plastic sack filled with five gallons of milk).

Then a buzzer sounded, and everyone drifted towards the lift door. The guy who’d been attending to The Cow passed me a loaf and the shift leader handed me one of the huge metal cups that went under the milkshake makers. The doors opened to reveal a wooden trolley and the smashed remains of what looked like half a roast ox.

God knows it was probably just a reasonable-sized roast, but it was big enough to have left ribs standing, with big gobbets of meat still adhering. There was blood-rare meat for those who wanted it, black cracklings for those who preferred them and under everything a thick pool of jellifying juice and fat.

I want to say we fell on it in like animals – the ancient buried drives of Italian peasants, surfacing from lymbic depths of satyric orgy. Actually, it was one of the most weirdly polite meals I’ve ever eaten. Six disgustingly filthy, sweaty men, offering each other food, pointing out choice pieces, introducing me to the etiquette as surely as Bedouin horsemen at a feast.

We drank milk and orange juice by the litre, built absurd sandwiches and dipped them in the mess on the silver plate. We laughed as the juices ran down our chins. Someone belched. The leader considered the noise, then nodded, as if it was his to mark out of ten and he was minded to be generous.

The bread, by today’s standards, was barbarous. It was fluffy, soft and white in a way I now know could only be achieved with machines and additives. The crust was elastic, sweet and a sort of caramel brown that bespoke all manner of interventions in its making. It had no redeeming features. But plunged into these juices… not just dipped into a modest superfluity of gravy or crumbled into a polite soup, but dug deep into an absurd excess… so much juice that we’d probably have to throw some of it away… running down our arms, spilling onto the floor… juices concentrated by heat, insanely over-seasoned. The plenty was intoxicating. You could feel the stuff radiating through your body like a shiver.

I grew, that summer. I grew a lot. I remember the diet that I’d eaten at home, that most of my friends would have recognised, was austere. Roast meat was for Sunday. Dipping bread was impolite. ‘French’ bread was posh. Milk was too expensive to drink by itself and orange juice was offered in shot glasses as a starter.

Every day, under the guidance of the satyrs, I ate and drank a month’s worth of the most luxurious ingredients any of our minds could have stretched to. The bread dipped in the juice was more than merely good – the act of dipping it was a rebellion against the restrictions of my childhood, a thrilling little political gesture against the small-town plutocrats upstairs. It bonded me to the dish washers, to Italians. It showed me that food is more than just itself, the sum of how and where it’s eaten and with whom it’s eaten. I’m still not sure of the medical truth of it, but I believe I came into the autumn about six inches taller, with huge shoulders, muscles everywhere, grinning like an idiot and looking like a recently sated Viking. My confidence had grown to a ridiculous degree, not from the ennobling effects of manual labour, but from the discovery of my defining vice. I had learned that I loved food and eating more than anything else. I knew who and what I was, and I rather liked it.

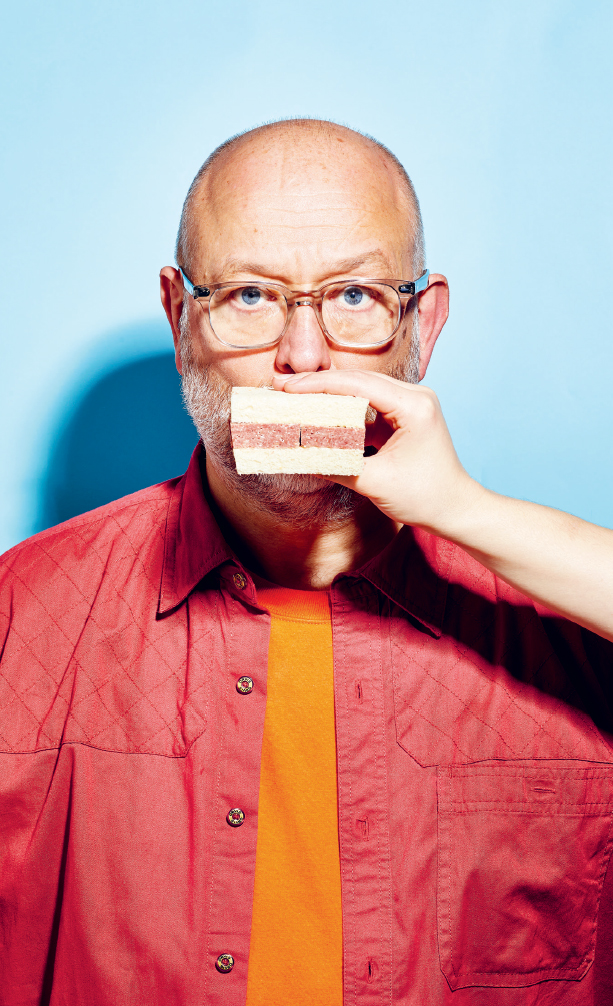

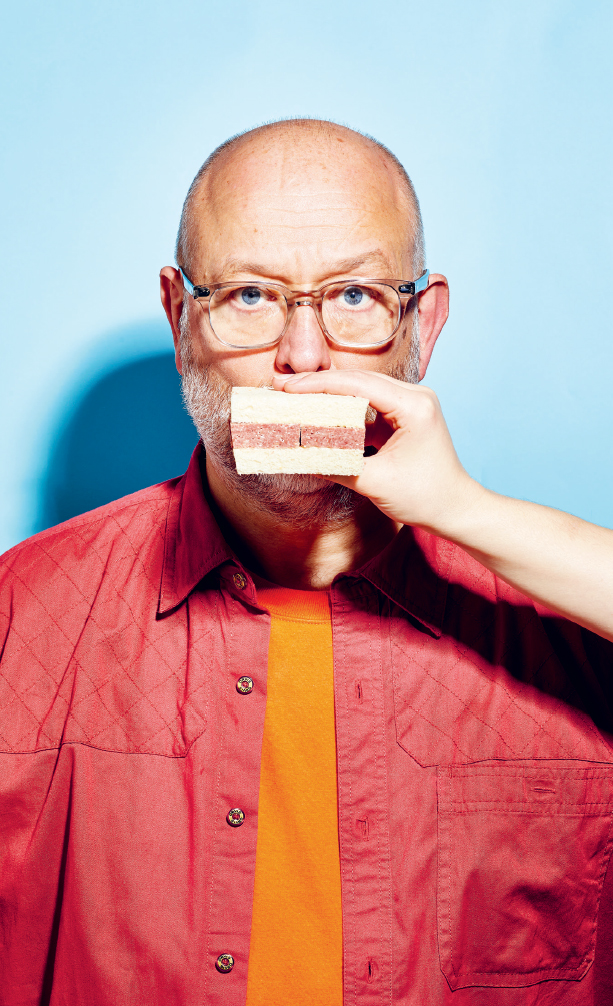

I’ll probably never get another crack at a carvery cart and a cow carcass, but to this day I revere Kitchen Bread beyond every other dish. Kitchen Bread isn’t a recipe – it isn’t even a type of bread. It’s the stuff you dip in while you’re cooking. It’s a private vice, just for cooks. It’s the ‘feedback’ loop that tells us that we’re doing it right; the way we check ourselves before we deliver to those we love. If your mind works that way (mine doesn’t), it’s a mildly transgressive thing to do. Dad had a different name for Kitchen Bread – he called it ‘cook’s perks’, and to some degree it is; a little perquisite with which we reward ourselves just before we serve. We have done well… we deserve it. But to me, it’s more. It reminds me who and what I am, and I still rather like it.

Making an illustrated food book is about a lot more than just writing it. It’s as much of a team effort as recording an album or making a film. I’m lucky enough to be able to work in a particular way with the very best. We’re in constant conversation from before pen hits paper and, when we finally assemble for the shoots, we spend weeks together, talking about food, cooking, shooting and eating it. To be honest, these are some of the happiest days in the whole process. Ideas flow, the text changes in response to the pictures, the design develops and all the time the final book is getting better and better. My name might be on the cover, but without these people there would be no book to put it on…

‘Snazzy’ Harry Webster is the Editor. This means she runs the project, coordinating everything from wrangling ketchup drips on the shoot to hammering my writing into coherence with such cheerful competence that you don’t quite notice how steely determined she is. Before she got her hands on it, what you are reading was an incoherent mess. Harry has strong opinions about many foods and seemingly an appetite for all of them.

Sam Folan is the Photographer, who should really have run away when we offered him this gig. We told him it was going to involve dishes that some people might find unappetising, strange, neglected recipes and a lot of brown food. Instead of fleeing, he got a strange look of enthusiasm in his eyes and started turning piles of wet mince into the kind of thing you want to hang on your walls. If you ever need it, and I hope you don’t, I reckon Sam could make a dead rat look delicious.

Sarah Lavelle is the Publisher. She’s able to look at a very odd pitch, see something in it that I wouldn’t have, then guide every step with a light hand until it arrives back from the printers… looking exactly as she’d planned all along.

Luke Bird is the Designer and Art Director. Because he’s there, at the early meetings about the shape of the book, and at the table for every single shot, he ties together the look of the whole thing. From the colour of a prop or the prominence of a drip of cheese right the way through to the placement of the last full stop, he makes sure everything reflects the main idea.

Out-of-frame is Faye Wears, the Props Stylist, whose diligence and creativity gave life to some very challenging dishes.

Brilliant and talented individuals, every one of them and, as a team – when fuelled by corned beef sandwiches and fine wines – utterly unsurpassed.

I thank them all.