Chapter 14

Psychotherapy for Children and Adolescents

John R. Weisz, Mei Yi Ng, Christopher Rutt, Nancy Lau, and Sara Masland

Efforts to help children and adolescents (henceforth “youth”) overcome behavioral and emotional problems are certainly as old as parenthood, but help in the form of psychotherapy may be traced back only about a century (Freedheim, Freudenberger, & Kessler, 1992). The work of Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) was pivotal, including his notion that even young children can be appropriate candidates for therapy. Classic steps in the birth of psychotherapy for young people included Freud's consultation with the father of “Little Hans” and his psychoanalysis of his own daughter, Anna (1895–1982), who became a prominent child analyst in her own right.

The rapid growth of youth psychotherapy was fueled by Freud's intellectual heirs and by models and methods very different from those of psychoanalysis, including an approach called “behaviorism.” Mary Cover Jones (1924a, 1924b), for example, used modeling and “direct conditioning” to help a 2-year-old boy overcome his fear of a white rabbit, thus helping launch a behavioral revolution in therapy. Psychoanalytic and behavioral therapies for young people developed alongside other treatments sparked by the grand theories of psychology and the humanistic tradition. Later Beck and colleagues helped develop cognitive therapy (e.g., Beck, 1970), and Meichenbaum and colleagues (e.g., Meichenbaum & Goodman, 1971) helped launch cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for children. By the late 20th century, youth psychotherapy had mushroomed dramatically. Indeed, Kazdin (2000) identified 551 different named therapies used with children and adolescents. Even this large number greatly underestimates the array of approaches used in practice, with hundreds of thousands of practitioners eclectically blending their different training backgrounds and theoretical orientations to form distinctive approaches unlike those of any other practitioner.

In this chapter we describe the field of youth psychotherapy that has grown up over the past century, emphasizing what research has shown and what remains to be learned. We begin by noting some of the factors that make psychotherapy different with youths than with adults. We describe strategies for studying youth psychotherapy and its effects, including meta-analytic approaches to synthesizing findings across multiple studies. In a section on evidence-based youth psychotherapies, we note how these are defined and identify the treatments identified as evidence-based in a recent series of systematic reviews. This is followed by a section on understanding how, with whom, and under what conditions the evidence-based therapies work—which requires a focus on the study of mediation and moderation. This is followed by a discussion of family factors in youth psychotherapy and efforts to test youth therapies with various population groups that are at special risk. We then view the field from the perspective of a friendly critic, noting limitations of current approaches and suggesting a series of strategies for strengthening youth treatments.

Psychotherapy With Youths Versus Adults: Some Key Differences

Although adult and youth psychotherapy have overlapping ancestry and are similar in many ways, important differences warrant attention. First, most treatment of boys and girls is prompted by parents, teachers, or other adults. It is adults who typically seek professional help, initiate the youth therapy, identify some or all of the referral concerns and treatment goals, pay the bills (or obtain the insurance coverage), and make the final decision as to how long therapy will last. Young people do participate as the “patients,” but the concerns they identify may not agree with those of their parents or other adults, and evidence suggest that they exert less influence than these adults on the focus and direction of therapy (Hawley & Weisz, 2003; Yeh & Weisz, 2001). With the impetus for youth psychotherapy coming mainly from adults, and adults influencing the goals of that therapy more than the youths, perhaps it is not surprising that youngsters often begin therapy with relatively low motivation for treatment. This can mean that a large component of youth therapy is engagement—that is, efforts by the therapist to build rapport, motivation, and a good therapeutic alliance with the young person.

Youth and adult psychotherapy also differ in the information sources available to therapists for planning treatment and tracking how it is going. Therapists working with young people almost invariably deal with information from their young patient as well as adults in the youngster's life—parents and teachers, for example. These different informants typically do not show very high concordance in the youth problems and strengths they report (Achenbach, McConaughy, & Howell, 1987; De Los Reyes, Goodman, Kliewer, & Reid-Quiñones, 2010; Richters, 1992). The accuracy of youth self-reports is limited by constraints on self-awareness and expressive and language ability. The accuracy of adult reports may be limited by lack of opportunity to observe youths in multiple settings, the effects of parents' own life stresses or mental health problems (see e.g., Kazdin & Weisz, 1998), and even by undetected agendas (e.g., high problem levels reported by adults who are desperate for help, or low levels reported by those who fear child protective services). Additionally, adults' reports of youths' behavior and reasons for referral can reflect the values, standards, practices, and social ideals of their cultural reference group (see Weisz, McCarty, Eastman, Chaiyasit, & Suwanlert, 1997). In sum, because youth therapy involves multiple stakeholders, each with different motivations, perceptions, and goals, assessing treatment needs, progress, and outcomes via information from these different stakeholders can magnify complexity in a way that appears less likely with adults.

Finally, boys and girls, much more than adults, are dependent on—and thus captives of—their externally engineered environments. Their family, neighborhood, and school contexts are largely selected and shaped by others, and in fact the “pathology” being treated may sometimes reside less in the youth than in the environment, which the youngster can neither escape nor alter significantly. The powerful impact of such factors as who lives in the home, how these people interact, what financial resources they have, and whether outside agencies (e.g., for child protection) are involved, may limit the impact of interventions that focus on the youth as solo or primary participant, highlighting a need to involve key members of the youth's social context in intervention (see, e.g., Henggeler, Schoenwald, Borduin, Rowland, & Cunningham, 1998), and sometimes making case management as salient as psychotherapy.

Studying the Effects of Youth Psychotherapy

Given the differences noted between youth and adult psychotherapy, it should be no surprise that separate treatments—albeit heavily influenced by adult approaches—have evolved for young people, together with a separate body of treatment outcome research. In contrast to the acceleration of youth psychotherapy practice over the past century, research tests of youth therapies took shape quite slowly, and only after a rough start. In 1952, Eysenck published a classic review of adult psychotherapy studies, raising serious doubts about whether therapy was effective. A few years later, Levitt (1957, 1963) reviewed treatment outcome research that included young people and concluded that rates of improvement in the youth samples were about the same with or without treatment. The studies available for those landmark reviews were irregular in quality. Treatment outcome research has grown more rigorous since those early days, treatments have evolved, and the number of youth outcome studies has increased dramatically, particularly in recent decades (see Silverman & Hinshaw, 2008; Weisz & Kazdin, 2010). The focus of youth treatment research has also sharpened over time, with a shift from studies of unspecified “treatment” for often vaguely specified youth problems to tests of specific, well-documented therapies for specific problems and disorders.

The benefit derived from youth treatment is often assessed in randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and these RCTs are often pooled and synthesized in meta-analyses (see later). Multiple baseline designs, ABAB (sometimes called reversal) designs, and other single-subject approaches are useful, as well. These approaches (well described in Barlow, Nock, & Hersen, 2009; Kazdin, 2011) have been used in a variety of youth treatment situations—such as programs for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; see, e.g., Pelham et al., 2010), studies where an entire classroom needs to receive an intervention (see, e.g., Wurtele & Drabman, 1984), and cases (sometimes involving rare conditions) where only one or two youngsters will be treated (e.g., McGrath, Dorsett, Calhoun, & Drabman, 1987; Tarnowski, Rosen, McGrath, & Drabman, 1987). These alternative outcome assessment designs have generated a rich body of outcome data and some useful meta-analyses, for example on treatment approaches for disruptive behavior (Chen & Ma, 2007), autism spectrum disorders (Campbell, 2003), and social skill deficits (Mathur, Kavale, Quinn, Forness, & Rutherford, 1998). However, meta-analyses in the field have most often focused on RCTs.

Meta-Analytic Findings

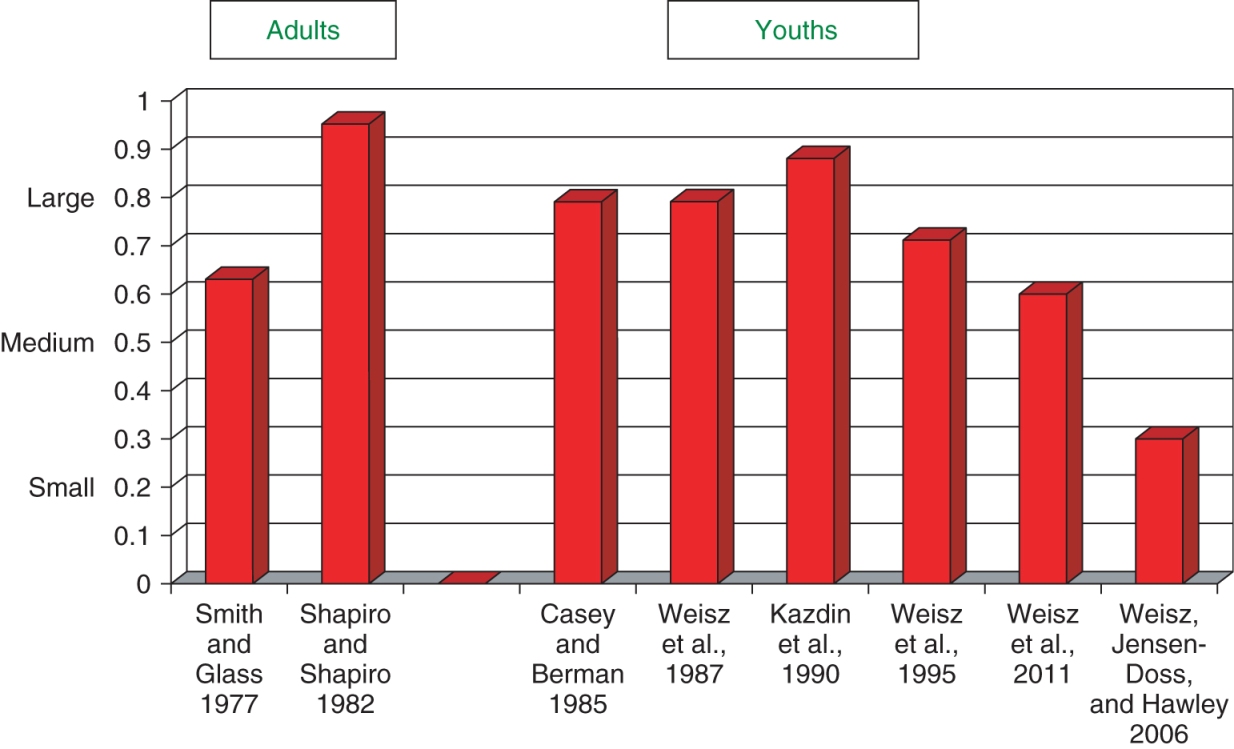

Among meta-analyses of the RCTs, a few have synthesized findings from particularly broad arrays of youth treatments and forms of dysfunction. In four particularly broad-based meta-analyses, encompassing more than 350 outcome studies, the meta-analysts imposed few limits on the types of treated problems or types of intervention that would be included. In the earliest of the four, Casey and Berman (1985) focused on studies with children age 12 and younger. Weisz, Weiss, Alicke, and Klotz (1987) included studies with 4- to 18-year-olds. Kazdin, Bass, Ayers, and Rodgers (1990) synthesized findings of studies with 4- to 18-year-olds. And Weisz, Weiss, Han, Granger, and Morton (1995) included studies spanning ages 2 to 18. Mean effect sizes found in these four meta-analyses are shown in Figure 14.1, with a comparison to two widely cited meta-analyses of predominantly adult psychotherapy (Shapiro & Shapiro, 1982; Smith & Glass, 1977). As the figure shows, the youth treatment effect sizes in Casey and Berman (1985), Weisz et al. (1987), Kazdin et al. (1990), and Weisz et al. (1995) fall roughly within the range of what has been found for adult therapy, and on average within the range of what Cohen (1988) suggests as benchmarks for medium (i.e., .5) to large (.8) effects. The last bar on the right in Figure 14.1 is discussed later in this chapter.

In addition to overall mean effects, two other youth meta-analytic findings sharpen the picture. First, findings (in Weisz et al., 1987; Weisz et al., 1995) indicate that effects measured immediately after treatment are quite similar to effects measured at follow-up assessments, averaging 5 to 6 months after treatment termination. This suggests that youth treatment benefit may have reasonable holding power. Second, findings on treatment specificity have shown that effects are larger for the specific problems targeted in treatment than for related problems that were not specifically addressed (Weisz et al., 1995, p. 460). This suggests that the tested therapies are not merely producing global “feeling better all over” effects, but instead are rather precise in impacting the forms of dysfunction they are designed to treat.

Although these findings suggest certain strengths of youth psychotherapies, meta-analysis can also be used to highlight challenges and critical questions for the field—for example, identifying problems and disorders for which youth treatment effects are modest, suggesting a need to strengthen interventions. Psychotherapies for youth depression, for example, appear to show more modest effects, on average, than treatments for a number of other youth problems and disorders (see Weisz, McCarty, & Valeri, 2006). Meta-analysis has also been used to evaluate the benefits of “evidence-based” psychotherapies, to which we now turn.

Identifying “Evidence-Based Psychotherapies”

As evidence accumulated over time showing beneficial effects of well-documented (typically manual-guided) psychotherapies for youths, adults, couples, and families, efforts were launched to identify the specific therapies sufficiently well-supported to be considered “empirically validated” or “evidence-based.” Various task forces and review teams were formed—notably the APA Division 12 Task Force on Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures, led by Dianne Chambless (see e.g., Chambless et al., 1998)—to distill the evidence from outcome studies and identify therapies that reached threshold for different levels of empirical support. Building on this work, experts in youth psychotherapy have conducted systematic literature reviews, in some cases including meta-analytic findings, to compile reports on evidence-based psychotherapies (EBPs) for young people (see Lonigan, Elbert, & Johnson, 1998; Silverman & Hinshaw, 2008). In the most recent report, edited by Silverman and Hinshaw (2008), reviewers identified psychotherapies that met criteria for status as well-established (e.g., two good group-design experiments by different research teams in two different settings, showing the treatment to be “superior to pill, psychological placebo, or another treatment”), probably efficacious (e.g., “at least two good experiments showing the treatment is superior…to a wait-list control group”), possibly efficacious (e.g., “At least one ‘good’ study showing the treatment to be efficacious in the absence of conflicting evidence”), or experimental (“not yet tested in trials meeting task force criteria”).

The reviewers in this 2008 report identified dozens of youth psychotherapies as either well-established or probably efficacious, spanning problem areas including early autism, anorexia nervosa, depression, anxiety disorders, ADHD, disruptive behavior problems and disorders, and substance abuse. Taken together, the reviews report a bumper crop of tested treatments, with more abundant lists in some treatment domains (e.g., conduct problems and anxiety) and more limited options in others (e.g., autism and eating disorders). Table 14.1 shows the treatments identified by the reviewers in the Silverman–Hinshaw (2008) special issue at the two highest levels of empirical support for various youth mental health problems and disorders.

Table 14.1 Youth Psychotherapies Identified as “Well-Established” or “Probably Efficacious”1,2. Tables can be downloaded in PDF formats at http://higheredbcs.wiley.com/legacy/college/lambert/1118038207/pdf/c14_t01.pdf.

|

| Table Layout Image |

Early autism

(Rogers & Vismara, 2008) |

Eating disorders in adolescence

(Keel & Haedt, 2008) |

Depression

(David-Ferdon & Kaslow, 2008) |

Phobic and anxiety disorders

(Silverman, Pina, & Viswesvaran, 2008) |

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

(Barrett, Farrell, Pina, Peris, & Piacentini, 2008) |

Youths exposed to traumatic events

(Silverman, Ortiz, et al., 2008) |

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

(Pelham & Fabiano, 2008) |

Disruptive behavior

(Eyberg, Nelson, & Boggs, 2008) |

Adolescent substance abuse

(Waldron & Turner, 2008) |

Specific Evidence-Based Treatments Identified as “Well-Established” and “Probably Efficacious”

As Table 14.1 shows, interventions for several forms of youth dysfunction were been rated probably efficacious or well-established by the reviewers. For purposes of this chapter, we refer to these interventions in Table 14.1 as evidence-based psychotherapies (EBPs) for youth.

Autism

The only autism treatment rated as a well-established EBP in the review by Rogers and Vismara (2008) was Ivar Lovaas's model of early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI; Lovaas, 1987; Smith, 2010), which involves individual discreet trials training (30 hours/week or more) to build, then scaffold, an array of specific core skills in such domains as language, self-help, and social interaction. Therapists provide treatment and train parents to conduct the intervention at home. Pivotal Response Training (PRT; Koegel, Koegel, Vernon, & Brookman-Frazee, 2010), rated probably efficacious, uses core skills of the Lovaas model but with an expanded emphasis on intervention in the child's natural environment and finding ways to boost motivation for learning (e.g., by using activities the youngster chooses and by identifying natural reinforcers). The treatment focuses on teaching communication, self-help, and academic, recreational, and social skills; parent training is a key component in reaching these goals.

Eating Disorders

Only one treatment for eating disorders was identified as an EBP by Keel and Haedt (2008). This was family therapy for anorexia nervosa, in particular the Maudsley model (Lock, Le Grange, Agras, & Dare, 2001). This model focuses on (a) “refeeding the client,” a process in which family members work to return the young client to more normal eating behavior; (b) negotiating improved relationships in areas that impact eating behavior [e.g., if the family uses deceit to avoid conflict and the youth hides bingeing through deceit, then therapy focuses on alternatives to deceit]; and (c) termination, which includes ways of sustaining healthy intrafamily relationships, appropriate boundaries, and increased youth autonomy. Keel and Haedt (2008) found no EBPs for bulimia nervosa in adolescents, but they noted that CBT (e.g., addressing distorted cognitions about body shape and size, using behavioral procedures to structure healthy eating habits, and using behavioral exposure to build resistance to triggers that spark cycles of bingeing and overcompensation) is a well-established treatment for bulimia in samples of young adults and older adolescents. A challenge in the eating domain is the array of different forms that eating disorders can take. Symptomatic of the problem is the fact that the most prevalent of all the eating disorder categories is “not otherwise specified.” Thus, even with effective treatments established for anorexia and bulimia, significant work will remain to encompass the full spectrum of dysfunctional eating behavior.

Depression

David-Ferdon and Kaslow (2008) placed two broad approaches to depression treatment—that is, Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Adolescents (IPT-A; Mufson, Weissman, Moreau, & Garfinkel, 1999) and CBT—within the upper two categories of empirical support. IPT-A focuses therapeutic attention on interpersonal issues that are common among adolescents, such as changes in the parent–teen relationship as roles shift; the intervention is designed to help adolescents deal with their difficulties in relation to role transitions and disputes, grief, and interpersonal deficits; an important goal is to help the adolescents develop effective strategies for addressing the difficulties. Although CBT has varied in specific contents across various treatment trials, it typically includes such core components as identifying and scheduling mood-elevating activities, identifying and modifying inappropriately negative cognitions, relaxation training, and learning and practicing problem-solving skills. An approach deemed “behavior therapy” was included among the probably efficacious EBPs for youths (e.g., Kahn, Kehle, Jenson, & Clark, 1990); the contents resembled CBT in most respects.

Anxiety Disorders

For phobic and anxiety disorders in youth (reviewed by Silverman, Pina, & Viswesvaran, 2008), the most extensively tested psychotherapies are the CBTs, which blend graduated exposure to feared stimuli with identification and modification of distorted cognitions that can stimulate and sustain unreasonable fears. Several forms of CBT were rated as EBPs. These included individual youth CBT, group CBT, and group CBT with parents. Silverman, Pina, et al. (2008) also classified Social Effectiveness Therapy for Children (Beidel, Turner, & Morris, 2000) as an EBP. This treatment, designed for social phobia, includes group sessions for the youngsters in treatment, in vivo exposure sessions (including practice interacting with nonanxious peers), and work with parents to help them reward their children's progress toward less anxious behavior in social situations.

In a complementary review, focused only on obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), Barrett, Farrell, Pina, Peris, and Piacentini (2008) identified a single EBP: individual exposure-based CBT. The core component is exposure and response prevention (ERP): Youths are repeatedly exposed to stimuli that trigger obsessive fears with the mandate not to engage in the compulsive behavior typically prompted by those fears. Over time, across repeated exposures, obsession-prompted anxiety is thought to dissipate via autonomic habituation. Cognition is considered central, as well, as the youths learn that feared consequences of refraining from the compulsive rituals do not actually materialize.

Finally, focusing on treatment of youths exposed to traumatic events, Silverman, Ortiz, et al. (2008) identified trauma-focused CBT (TF-CBT; Cohen, Mannarino, & Deblinger, 2010) as an EBP. This treatment, designed for youngsters who have experienced sexual abuse and other forms of maltreatment, uses core components of CBT for anxiety, but with important additions tailored to fit the situations in which youngsters have experienced trauma. These include safety planning (to reduce future environmental risk) and the use of a “trauma narrative,” in which young people describe, in writing, their traumatic experiences. The narrative is first created in draft form, then read repeatedly in the presence of the therapist, as a form of exposure therapy. Distorted cognitions are addressed by modifying parts of the narrative—for example, by altering inappropriate self-blaming statements. Caregivers participate in the process, including by joining therapist and youth at later readings of the narrative and offering support for the youth's courage in sharing the story. Silverman, Ortiz, et al. (2008) also identified school-based group CBT (Kataoka et al., 2003; Stein et al., 2003) as an EBP. This treatment, designed for youths who have experienced trauma via exposure to community violence, includes psychoeducation, cognitive and coping skills training, social skills training, and graduated exposures in the form of writing and/or drawing activities.

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Pelham and Fabiano (2008) identified three treatments for ADHD as well-established. One was behavioral parent training, in which parents are taught a set of techniques (e.g., clear instructions, differential attention for desired versus undesired behavior, use of praise and reward, time-out) for effective behavior management. A second was behavioral contingency management in classrooms. The third was intensive peer-focused behavioral interventions in recreational settings (e.g., summer day camps). The model program of this type is Pelham's Summer Treatment Program (Pelham et al., 2010), in which youngsters are immersed in sports, academic, and social skill-building activities, all within the context of carefully-structured behavioral contingencies, and complemented by behavioral training and consultation with caregivers. Significantly, Pelham and Fabiano (2008) did not find empirical support for cognitive-behavioral or nonbehavioral treatments for ADHD youths.

Conduct-Related Problems and Disorders (Disruptive Behaviors)

In their review focused on disruptive behavior, Eyberg, Nelson, and Boggs (2008) identified a remarkable 16 EBPs. These included behavioral parent-training programs, some emphasizing parent management training (Forgatch & Patterson, 2010; Kazdin, 2010), some emphasizing real-time coaching during parent–child interaction sessions (e.g., McMahon & Forehand, 2003; Zisser & Eyberg, 2010), and one involving parent training at different levels of intensity delivered within a public health dissemination framework (Sanders & Murphy-Brennan, 2010). A video-guided approach developed by Webster-Stratton and colleagues (e.g., Webster-Stratton & Reid, 2010) includes programs for behavioral training with parents in groups and problem-solving and social skills training with children (ages 3 to 8) in groups; in these programs, shown to be beneficial independently and in combination, participants view and discuss video clips illustrating effective and ineffective strategies and apply what they learn to their own behavior. Other EBPs for conduct problems include cognitive and behavioral training programs to enhance anger management (Lochman, Boxmeyer, Powell, Barry, & Pardini, 2010), problem-solving skill (Kazdin, 2010), and appropriately assertive social behavior (Huey & Rank, 1984), as well as a school-based program, based on rational-emotive theory, designed to reduce disruptive and disobedient behavior by helping youths learn to make accurate cognitive appraisals of self and social situations (Block, 1978).

Finally, two EBPs blend behavioral training for caregivers with methods for engaging others in the youth's social system. These include the extensively studied Multisystemic Therapy (MST; Henggeler & Schaeffer, 2010), developed originally for delinquent youths but extended to treatment of other forms of youth dysfunction (e.g., sexual offending, suicidal behavior), and Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care (MTFC; Smith & Chamberlain, 2010), designed to provide effective foster care for disruptive youths in the child welfare system. Both MST and MTFC are discussed in greater detail later in this chapter.

Adolescent Substance Abuse

EBPs for adolescent substance abuse have focused most heavily on alcohol and marijuana use. For these and other substances, Waldron and Turner (2008) identified three EBPs that use a blend of behavioral methods, family systems perspectives, and outreach to systems outside the family. One of these, functional family therapy (FFT; Alexander & Parsons, 1982; Sexton, 2010), combines reliance on core behavioral techniques and a family systems orientation in an effort to establish new patterns of family interaction, and therapists work with external systems such as schools and probation departments to maximize generalization in the community. In addition, both individual and group CBT approaches (see Waldron & Kaminer, 2004) were identified as EBPs. In general, these combine an emphasis on identifying and modifying distorted cognitions with an emphasis on behavioral coping skills needed to avoid substance use (e.g., coping with cravings, refusal in the face of social pressure, avoiding situations where substance use might be likely).

Understanding How, With Whom, and Under What Conditions Treatments Work

Identifying youth EBPs can be useful in a number of ways. The process can prompt detailed reviews of the evidence base, nudging experts in the field into periodic self-study and encouraging a kind of “taking stock” of what has been learned about how to help youths and families deal with dysfunction in various forms. Identifying efficacious treatments can also serve as a springboard, encouraging an understanding of the treatments that goes deeper than just finding out that they “work.” Logical next questions can include, for example, how (i.e., through what processes) the treatments work, with whom they work, and under what conditions they work—questions to which we turn next (see also Chapter 2, this volume, for an overview of mediators and moderators).

Mediators and Mechanisms of Change

Ultimately, understanding how a treatment works requires identifying mechanisms of change (also known as mechanisms of action), the specific processes through which the treatment produces outcomes. A sound understanding of these mechanisms could help treatment developers strengthen the active ingredients of psychotherapy and reduce or eliminate inactive components, thereby increasing efficacy, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness of the therapy (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002). A useful first step in identifying change mechanisms is testing whether a particular variable is a mediator of treatment outcome in a RCT, that is, an intermediate variable evident during treatment that statistically accounts for the treatment-outcome relationship (Kazdin, 2007; Kraemer et al., 2002; Weersing & Weisz, 2002b).

Moderators of Treatment Outcome

In addition, researchers try to understand with whom treatments work and under what conditions they work, by studying moderators of treatment outcome. In the context of an RCT, a moderator is a variable present prior to randomization that interacts with treatment condition; that is, the effects of that treatment on outcome depend on the level of the moderator (Kraemer et al., 2002). Identifying treatment moderators can inform efforts to establish the boundaries of treatment benefit. For example, identifying client characteristics that moderate treatment effects can help investigators learn which groups benefit most, and least, from various treatments (Kraemer et al., 2002), and this information can be used to guide decisions about which treatments to employ with which groups, so as to optimize the effects of psychotherapy.

Mediators and Moderators Identified in Studies of Evidence-Based Psychotherapies

In the following sections, we review examples of findings on mediators and moderators of youth EBPs derived from treatment outcome studies. We focused only on those treatments identified as well-established and probably efficacious psychotherapies, as discussed in the previous section and shown in Table 14.1, and on treatment rather than prevention studies (i.e., the sample has to have elevated symptoms of a disorder to be recruited into the treatment study). Because a larger number of moderators have been identified in individual trials of youth therapies, we focused on the most robust ones, and where possible those that reach significance in meta-analyses. We limited our review of moderators to meta-analyses of randomized trials when available; otherwise, we extended our review of moderators to meta-analyses that include both randomized and nonrandomized trials and to individual RCTs. In the meta-analyses reviewed, we focused on moderators of between-group (treatment versus control) effect sizes rather than moderators of pre- to posttreatment effect sizes because the former type of moderator is conceptually similar to moderators in an individual RCT, whereas the latter type of moderator is more similar to predictors in an individual RCT.

Mediators and Moderators of EBPs for Autism

We did not find any research examining mediation of the effects of EIBI or PRT. The absence of studies examining mediation of EBPs for autism may be due in part to the small number of RCTs in this area and to the fact that the low prevalence rate of the condition makes it difficult to obtain the large study samples needed for properly-powered mediation testing. Two promising candidates—social initiations (i.e., behaviors aimed at seeking help, attention, or social interaction) and peer social avoidance—were identified by Rogers and Vismara (2008) as targets for future research on mediation in autism treatment.

Several moderators of EIBI or similar early behavioral treatments have been identified. Consistent with expectations, several characteristics of the treatment including higher treatment intensity, longer treatment duration, and the presence of a parent training component were associated with significantly larger between-group effect sizes in a meta-analysis that included randomized and nonrandomized trials (Makrygianni & Reed, 2010). Only one characteristic of the sample emerged as a significant moderator in the same meta-analysis; higher baseline adaptive functioning was associated with larger between-group effect sizes. Interestingly, higher baseline intellectual and language abilities did not moderate treatment effects (Makrygianni & Reed, 2010). The association between younger age and larger treatment effects approached significance (Makrygianni & Reed, 2010); the failure to reach significance may have been due to a ceiling effect because a mean sample age of 54 months or younger at baseline was an inclusion criterion in this meta-analysis. Makrygianni and Reed (2010) observed that studies with mean child age of 35 months or younger and treatment intensity of more than 25 weeks seemed to have larger pre-post effect sizes, but they did not subject this observation to a statistical test. We did not find any studies examining moderators of PRT, but research (Sherer & Schreibman, 2005) on behavioral profiles of responders and nonresponders to PRT may point to promising candidate moderators for future study. Clinical practice implications are limited thus far, given the small number of significant findings, but EIBI moderator evidence does suggest that better treatment outcomes for early intervention are associated with higher treatment intensity and longer duration, plus inclusion of parent training.

Mediators and Moderators of EBPs for Eating Disorders

A recent study (Le Grange et al., 2012) tested six candidate mediators of the effects of family therapy, compared to adolescent-focused therapy, on rates of remission among adolescents with anorexia nervosa. None of the candidates—changes in weight, restraint in eating, depressive symptoms, self-esteem, self-efficacy, and parent self-efficacy after 4 weeks of treatment—were significant treatment mediators. The mediators were tested separately in two subgroups based on a median split of the adolescents' baseline severity of eating-related obsessions and compulsions (because this was a significant moderator), which may have limited the power to detect significant mediation, according to Le Grange and colleagues (2012).

We found a few moderators of family therapy effects for adolescent anorexia in individual RCTs, but not in meta-analyses. Eating- and weight-related obsessions and compulsions were significant moderators of treatment outcome in two RCTs. Adolescents with more severe obsessions and compulsions benefited more from a year-long course of family therapy compared to adolescent-focused therapy of the same duration (Le Grange et al., 2012), and compared to a shorter 6-month course of family therapy (Lock, Agras, Bryson, & Kraemer, 2005), even though the treatments worked equally well for the whole sample. Adolescents with more severe eating disorder symptoms also benefited more from year-long family therapy than adolescent-focused therapy (Le Grange et al., 2012). Interestingly, other measures of baseline psychopathology (e.g., body mass index, comorbidity, internalizing symptoms) did not moderate treatment effects (Le Grange et al., 2012; Lock et al., 2005). These findings imply that adolescents with more severe psychopathology specific to eating disorders would respond best to a year-long course of family therapy, but that those with milder eating disorder psychopathology may respond well to family therapy (year-long or 6-month) or adolescent-focused therapy.

There are mixed findings on whether intact family status and parental Expressed Emotion (EE; Hooley & Parker, 2006)—critical, hostile, and emotionally overinvolved attitudes toward the patient by close family members—moderate family therapy outcomes for adolescent anorexia nervosa. Adolescents from nonintact families benefited more from the year-long course than the 6-month course of family therapy in one study (Lock et al., 2005), but benefited equally from family therapy and adolescent-focused therapy when both treatments lasted a year. This suggests that adolescents from nonintact families may simply need longer treatment, regardless of whether the treatment was focused on the family or on the adolescent. In addition, adolescents whose mothers displayed higher levels of critical EE (i.e., made three or more criticisms in a structured interview) responded significantly better to separated family therapy (i.e., adolescent and parents seen separately) than to conjoint family therapy (i.e., adolescent and parents seen together), whereas adolescents whose mothers displayed lower levels of critical EE (i.e., fewer than three criticisms) responded equally well to both kinds of family therapy at posttreatment and at 5-year follow-up (Eisler et al., 2000; Eisler, Simic, Russell, & Dare, 2007). The authors suggested that maternal criticism during treatment sessions may trigger feelings of guilt and blame, thereby attenuating treatment effects. However, EE did not significantly moderate outcome when family therapy was compared to adolescent-focused therapy in another RCT, possibly because separated family therapy targets the reduction of parental criticism whereas adolescent-focused therapy targets increases in the adolescent's autonomy (Le Grange et al., 2012). Implications for clinical practice with high EE families are to conduct separate therapy sessions for adolescents and parents and to make reduction of parental criticism a focus of treatment.

Mediators and Moderators of EBPs for Depression

Several RCTs have found cognitive variables to be significant mediators of CBT for youth depression. Explanatory style mediated outcomes for youths with elevated depressive symptoms, whereby shifts to less pessimistic (Jaycox, Reivich, Gilham, & Seligman, 1994) or more optimistic (Yu & Seligman, 2002) attributional patterns were associated with reduced depressive symptoms. In addition, reductions in negative cognitions mediated reductions in depressive symptoms among depressed adolescents (Ackerson, Scogin, McKendree-Smith, & Lyman, 1998; Kaufman, Rohde, Seeley, Clarke, & Stice, 2005; Stice, Rohde, Seeley, & Gau, 2010). However, findings are not consistent between and even within studies. Ackerson et al. (1998) found that reductions in negative cognitions as assessed by the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS; Weissman, 1979) but not by the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ; Hollon & Kendall, 1980) mediated outcome. Conversely, Kaufman et al. (2005) showed the opposite pattern of results—the ATQ but not the DAS mediated outcome. To explain their findings, Kaufman et al. (2005) suggested that their version of CBT may have been able to change cognitions only at the level of negative automatic thoughts as measured by the ATQ, and that more intensive CBT may be required to change more entrenched core beliefs as measured by the DAS. However, Ackerson et al.'s (1998) version of CBT, cognitive bibliotherapy, was unlikely to be more intensive than Kaufman et al.'s (2005) in-person group CBT. Evidently, more research is needed to clarify these mixed findings.

Several other variables have been tested as potential mediators in the context of CBT for adolescent depression. Increased frequency of engaging in pleasant activities was a significant mediator in one RCT (Stice et al., 2010) of group CBT for adolescents recruited for treatment from high schools due to their elevated depressive symptoms, but not in another RCT (Kaufman et al., 2005) of group CBT for adolescents with diagnoses of major depression and comorbid conduct disorder referred for treatment by the juvenile justice system. These findings provide preliminary evidence that mediators may differ according to severity and comorbidity of the sample, as well as referral source, but of course any two studies will differ along so many dimensions that ferreting out the cause of different findings is essentially educated speculation. Other candidate mediators—frequency of engaging in relaxation, social problem solving, and youth–therapist alliance—were also not found to mediate treatment outcome in the sample with major depression and comorbid conduct disorder (Kaufman et al., 2005). Finally, readiness to change mediated treatment outcome in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (Lewis et al., 2009), with adolescents receiving CBT or combination treatment of CBT and fluoxetine displaying the greatest increase in readiness to change.

To summarize, there is some evidence that shifts in explanatory style may mediate CBT effects for child depression, mixed evidence that change in negative cognitions and engagement in pleasant activities are mediators of CBT effects for adolescent depression, and limited evidence that readiness to change is a mediator of CBT effects for adolescent depression. Future research will be needed to determine which of these findings can be replicated, to clarify inconsistencies, and also to demonstrate temporal precedence of the mediators relative to change in depression levels. In the only study that documented the temporal relations of the mediators and outcome (Stice et al., 2010), fewer than 10% of youths showed a meaningful change (defined as 0.33 SD) in each of the two mediators (ATQ and engagement in pleasant activities) before a meaningful reduction in depressive symptoms. This raises a question as to whether change in cognitions and engagement in pleasant activities operate as true mechanisms of change in depression treatment, a question that warrants attention in future research (see our discussion of future research on mechanisms of change, below; see also discussion of mediation in Chapter 9, this volume). Future research will also be needed to help identify mediators of change in the context of IPT-A for adolescents and of behavior therapy for children; we have not identified any mediation research with these EBPs.

Moderators identified from meta-analyses of RCTs of psychotherapy for youth depression that included EBPs as well as non-EBPs include informant (i.e., who reports on the depression; Weisz, McCarty, et al., 2006) and depression severity at baseline (Watanabe, Hunot, Omori, Churchill, & Furukawa, 2007). Larger treatment effects were associated with youth-report than parent-report measures (see our later section on informant effects), and with higher baseline severity compared to lower baseline severity, possibly because youths with more severe psychopathology have more room for improvement. Youth age was a significant moderator in one of the meta-analyses (Watanabe et al., 2007), with larger effects obtained for adolescents than for children, but not in the other (Weisz, McCarty, et al., 2006). The positive finding, though not evident in both meta-analyses, is consistent with the idea that adolescents' more advanced cognitive level makes them better able than children to grasp concepts discussed in therapy.

Mediators and Moderators of EBPs for Phobic and Anxiety Disorders

Reductions in youths' anxious self-statements and improvements in the ratio of positive self-statements to the sum of positive and anxious self-statements (their “states of mind ratio”) mediated youth-reported symptom reduction in two RCTs (Kendall & Treadwell, 2007; Treadwell & Kendall, 1996) of individual CBT for youth anxiety. Positive self-statements and depressive self-statements, by contrast, were not found to mediate treatment outcome (Kendall & Treadwell, 2007; Treadwell & Kendall, 1996). Another research team (Lau, Chan, Li, & Au, 2010) has replicated the mediating effects of anxious self-statements on outcome in group CBT for youth anxiety; this team also demonstrated that improvement in the youths' ability to cope with fear-inducing situations, as perceived by youths and by parents, mediated treatment-induced symptom reduction.

As with CBT for youth depression, future research will need to demonstrate temporal precedence for the above mediators of individual CBT and group CBT, relative to changes in youth anxiety symptoms, to be considered true mechanisms of change. Future research will also be needed to identify mediators associated with other EBPs for phobic and anxiety disorders (i.e., group CBT for social phobia, group CBT with parents, and social effectiveness training for social phobia).

Studies conducted in North America had larger effects than studies conducted elsewhere, but there appeared to be no other moderators of treatment outcome according to a meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized trials of psychosocial treatments for youth anxiety (Silverman, Pina, et al., 2008). Another meta-analysis (James, Soler, & Weatherall, 2005) that included only RCTs of CBT compared to a wait-list or attention control detected no heterogeneity among the 13 studies, suggesting that there were no robust moderators of CBT for youth anxiety. These findings suggest that more work needs to be done on adapting CBT for youth anxiety to cultures and treatment contexts outside North America, but otherwise, research has not yet found marked differences in anxiety treatment response between different groups of youths.

Mediators and Moderators of EBPs for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

As best we can determine, no mediators or moderators have been identified for individual exposure-based CBT to date. This gap in the evidence-base has been attributed to small sample sizes and the low power of treatment outcome studies of psychotherapy in this area (Barrett et al., 2008). Comorbid tic disorder was found to be a moderator of the effects of sertraline treatment, but not of CBT. Because youths with comorbid tic disorder did not respond well to medication alone in the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS), CBT alone or combined with medication has been recommended as a first-line treatment for these youths (March et al., 2007).

Mediators and Moderators of EBPs for Youths Exposed to Traumatic Events

We have not found good evidence for any mediators of TF-CBT or of school-based group CBT. A review by Cohen et al. (2010), creators of TF-CBT, suggests that potential candidates for a mediation role in TF-CBT might include parent emotional distress, parent support, and abuse-related attributions and perceptions of the youth (e.g., youths believing they are responsible for the abuse, perceiving that others do not believe their accounts of abuse, or feeling different from their peers; see Cohen & Mannarino, 2000).

We did not find any meta-analyses of CBT for youths exposed to traumatic events, and RCTs did not report significant moderators. One meta-analysis (Silverman, Ortiz, et al., 2008) that included both EBPs and non-EBPs for youths exposed to trauma suggested that treatment orientation, type of trauma, and parent involvement were moderators of treatments; differences between effect sizes at each level of the moderators were compared but not subjected to significance testing. As expected, CBT interventions performed better than non-CBT interventions, but surprisingly, youth-only interventions performed better than those with parent involvement (Silverman, Ortiz, et al., 2008). In addition, interventions for sexual abuse had relatively large effects on posttraumatic and depression symptom outcomes and relatively small effects on externalizing symptoms, compared to interventions for other types of trauma (Silverman, Ortiz, et al., 2008). The authors speculated that internalizing symptoms may be more severe in sexually abused youths, leading to a treatment focus on reducing internalizing symptoms among these youths, whereas the treatment focus may be on reducing externalizing symptoms among youths with other kinds of trauma such as physical abuse. Future research should confirm if the above findings are statistically significant (i.e., not merely due to chance), and if so, probe the underlying processes that explain these moderation effects.

Mediators and Moderators of EBPs for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

The Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD (MTA; MTA Cooperative Group, 1999a), the largest RCT of ADHD treatments to date, compared behavioral treatment (i.e., behavioral parent training, summer treatment program, and teacher consultation emphasizing behavioral classroom management), medication management (methylphenidate, Ritalin), a combination of behavioral treatment plus medication, and regular community care. Youths receiving combination treatment or medication only did better than those receiving behavioral treatment only or community care. The superior effects of the combination treatment on youth social skills relative to community care were mediated by reductions in negative/ineffective discipline by parents (Hinshaw et al., 2000). Although both combination and behavioral treatments improved discipline, improved discipline was associated with improved youth social skills for the combination treatment only. It is possible that reduced behavior problems due to stimulant medication caused parents to use less harsh discipline, resulting in improved self-regulation by their children. It is also possible that improved social skills, driven by medication, caused parents to use less harsh discipline because temporal relationships between mediator and outcome could not be distinguished. Furthermore, a third variable could have driven improvements in both discipline and social skills (Hinshaw et al., 2000). It is noteworthy that other parent variables (i.e., attendance at behavioral treatment sessions, positive involvement, deficient monitoring) were not mediators of behavioral or combination treatment effects (Hinshaw et al., 2000; MTA Cooperative Group, 1999b).

Publication year was a moderator of outcome in a meta-analysis (Fabiano et al., 2009) of behavioral treatments for ADHD, with more recent publications associated with smaller effects, but various participant and family characteristics were not. The publication year finding is puzzling, in that treatments might be expected to become more effective with improved understanding of ADHD and intervention effects over the years. In another meta-analysis (Corcoran & Dattalo, 2006) of behavioral and cognitive-behavioral interventions for ADHD with parent involvement, two-parent households and older youths were associated with larger treatment effects. Finally, the MTA study identified a moderator that has noteworthy implications—youngsters with comorbid anxiety disorder benefited more from behavioral treatment than did those with no anxiety disorder. The anxious youths showed outcomes comparable to those of the medication management group and superior to those of the community care group (MTA Cooperative Group, 1999b). Thus, Hinshaw (2007) has suggested that behavior therapy alone may potentially be a suitable first-line treatment for the subgroup of youths with ADHD who have comorbid anxiety.

Mediators and Moderators of EBPs for Disruptive Behavior Problems

Research on mediators of EBPs for disruptive behavior problems is especially rich compared to other problem areas. This reflects, in part, the fact that treatment in this area has been such a priority for the field, generating so much treatment development and intervention testing.

Most mediators identified across the various EBPs for disruptive behavior are some aspect of parent/caregiver practices and skills. This is consistent with expectations given that the parent or caregiver is seen as the principal change agent in most EBPs for disruptive behavior and is taught parenting skills in a number of domains, such as close monitoring of the youth, and preventing the youth from associating with deviant peers. For example, in MST, improved family and peer functioning were found to mediate reductions in delinquent behavior (Huey, Henggeler, Brondino, & Pickrel, 2000). In addition, caregivers' improved ability to follow through with disciplinary action and decreased concern about youths' negative peer relationships partially accounted for the superiority of MST over usual care in the treatment of juvenile sex offenders (Henggeler et al., 2009). Similarly, in MTFC, improvement in caregivers' family management skills (e.g., adult–youth relationship, supervision, discipline) and reduction in youths' relationships with deviant peers mediated treatment effects on the subsequent antisocial behavior of adolescent boys who were severe offenders (Eddy & Chamberlain, 2000). In addition, decreases in harsh, critical, and ineffective parenting practices accounted for reductions in youth externalizing symptoms in a study (Beauchaine, Webster-Stratton, & Reid, 2005) that pooled data from six RCTs of the Incredible Years (IY) treatment program in which participants received various combinations of child, parent, and/or teacher training. Interestingly, other aspects of parenting and peer relationships (i.e., caregiver monitoring, parent–youth communication, and peer delinquent behaviors and conventional activities) were not mediators in the Henggeler et al. (2009) study of sex offender treatment, suggesting that just which aspects of parenting need to be altered to generate youth behavior change may depend on the specific EBP or the condition being treated.

Youth-focused variables have also been shown to mediate outcomes of EBPs for disruptive behavior problems, but these mediators seem to be specific to the particular EBP or sample. Homework completion—a measure of engagement in school—mediated the effects of MTFC on the number of days offending girls spent in locked settings (Leve & Chamberlain, 2007). In addition, changes in boys' hostile attributions, reduced expectations that aggression would result in favorable outcomes, and increased internal locus of control, among other changes, accounted for improvements in school behavior, delinquency, and substance use among youths receiving anger control training (Lochman & Wells, 2002). This is not surprising given the emphasis in this treatment program on individual changes in the youths themselves.

It is encouraging that multiple studies by different research teams have converged on the conclusion that parenting practices and relationships with deviant peers mediate the effects of EBPs on disruptive behavior among youths. Indeed, this may be the most robust finding on any mediator of any EBP for youths. Evidence on youth-focused mediators are more limited and more in need of replication. As with EBPs for depression and anxiety, RCTs of EBPs for disruptive behavior will need to include multiple assessments of both mediators and outcomes during and after therapy to establish identified mediators as true mechanisms of change (see our later section on this topic).

Several moderators of behavioral parent training were identified in a meta-analysis (Lundahl, Risser, & Lovejoy, 2006) that included randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials. Youths from nonintact and economically disadvantaged families made smaller treatment gains than those not in these subgroups. It is probable that single and economically disadvantaged parents have less time and energy to attend all therapy sessions, to practice the parenting skills learned during therapy at home, and to monitor and regulate their children's peer associations. Lundahl et al. (2006) examined moderators of outcome within the group of studies with economically disadvantaged samples and found that individual parent training was more helpful than group parent training, suggesting that close individual attention may be especially helpful with economically disadvantaged families. Interestingly, treatments that involved only parents were associated with better outcomes in parent behavior and perceptions than were treatments that involved both parents and their children. An explanation proposed by Lundahl et al. (2006) is that parents may be more likely to see themselves as the primary agents of change and take more responsibility for effecting change when they are the sole recipients of treatment. In addition, studies with samples including clinically significant disruptive behavior problems showed larger treatment effects, possibly because there was more room for improvement in those samples.

Mediators and Moderators of EBPs for Adolescent Substance Abuse

Mirroring the mediation research on EBPs for ADHD and disruptive behavior problems, a change in parenting practices was a significant mediator of an EBP for adolescent substance abuse. MDFT improved parental monitoring of adolescents' daily activities and peers relative to peer group intervention, thereby increasing abstinence from substance use during a 12-month period following baseline assessment (Henderson, Rowe, Dakof, Hawes, & Liddle, 2009). Interestingly, improved parental monitoring mediated treatment effects only when the outcome was proportion of youths who were abstinent and not frequency of substance use, leading Henderson and colleagues (2009) to suggest that parental monitoring may prevent substance use, but not reduce substance use among adolescents who continue using substances after treatment. Improved parent-adolescent relationship quality, although associated with greater abstinence, was observed in both MDFT and peer group intervention conditions and thus was not a treatment mediator (Henderson et al., 2009). We do not know of any published mediation studies for other EBPs of adolescent substance abuse, but Waldron and Turner (2008) have suggested several candidates to examine, including family variables in FFT and MST, coping skills in individual and group CBT, and therapeutic alliance for all treatment approaches.

We found several individual RCTs, but no meta-analyses, that identified moderators of EBPs for adolescent substance abuse. MDFT outperformed two alternative treatments (individual CBT and enhanced treatment as usual) for adolescents with more severe baseline substance use and comorbidity, but performed similarly to the alternative treatments for adolescents who had less severe baseline substance use and comorbidity (Henderson, Dakof, Greenbaum, & Liddle, 2010). The authors suggested that common factors of good psychotherapy (e.g., strategies to engage adolescents, sufficient duration and intensity) may be adequately therapeutic for adolescents with less psychopathology, whereas MDFT's specific focus on changing a greater number of documented risk factors, particularly family interactions, may be especially beneficial to adolescents with more psychopathology. Gender appears to moderate the effects of CBT on substance use, but findings are mixed on the direction of moderation, with one RCT favoring boys (Kaminer, Burleson, & Goldberger, 2002) and another favoring girls (Kaminer, Burleson, & Burke, 2008). The first RCT tested group CBT against a group psychoeducation control whereas the second RCT tested an aftercare intervention that included CBT and motivational enhancement therapy delivered either in-person or through the phone against a no aftercare control group after all participants completed group CBT. The discrepancy on the direction of moderation could reflect different processes involved in the initiation versus maintenance of behavior change (Kaminer et al., 2008), the use of different intervention approaches, or the presence of motivational enhancement therapy in the one instance. In other findings, several personality and temperament variables have been shown to moderate the effects of group CBT, including sensation seeking, anxiety sensitivity, hopelessness (Conrod, Stewart, Comeau, & Maclean, 2006) and rhythmicity (Burleson & Kaminer, 2008). These are early days for research on moderation in substance abuse treatment, but as future studies document which of these specific findings can be replicated, treatment may be optimized for substance-using adolescents by first screening them for personality/temperament variables and then matching them to treatments that have been documented to be more beneficial for individuals with their particular personality/temperament type.

Therapeutic Alliance and Other Relationship Variables

Notably absent from our review of mediators of youth EBPs are therapeutic alliance and other therapeutic relationship variables, which have been hypothesized to be key mechanisms of change in youth psychotherapy (Karver, Handelsman, Fields, & Bickman, 2005, 2006; Shirk & Karver, 2003). Unfortunately, we have only identified one youth RCT that has tested alliance as a mediator, and it found therapeutic alliance not to be a significant mediator (Kaufman et al., 2005; see our section on mediators and moderators of EBPs for depression). This dearth of research on alliance as a mediator is disappointing given the substantial number of studies that have examined the association between alliance and outcome in youths, as well as the intuitive belief by many that youngsters who see their therapist as understanding them and collaborating with them will have better outcomes. Evidence for this belief, via appropriate mediation testing, is absent thus far.

A meta-analysis (Karver et al., 2006) documented significant associations between a number of different therapeutic relationship variables (e.g., counselor interpersonal skills, therapist direct influence skills, youth affect toward therapist) and outcome. More recently, another meta-analysis (McLeod, 2011) with an exclusive focus on therapeutic alliance (rather than the broader construct of therapeutic relationship) and outcome in youth psychotherapies found a small but significant association (r = 0.14), with roughly equal associations for the alliance between youth and therapist (youth–therapist alliance) and the alliance between parent and therapist (parent–therapist alliance). This alliance–outcome association from 38 youth psychotherapy studies is half of that found in a meta-analysis of 190 adult psychotherapy studies (r = 0.275, Horvath, Del Re, Flückiger, & Symonds, 2011). Why is the alliance–outcome association so much weaker in youth psychotherapies than in adult psychotherapies? McLeod (2011) suggested that the moderators identified in his meta-analysis may provide clues to explain the smaller association in youth psychotherapies. Two of these moderators—therapeutic orientation and informant—may be especially pertinent to this question. Smaller alliance–outcome associations emerged for family-based or systemic therapies compared to individual-based youth or parent therapies and for youth- or observer-report compared to parent-report measures of alliance. Because family-based and systemic therapies are more common among youth than adult clients, the smaller alliance–outcome association of these therapies may have brought down the mean association across youth psychotherapies. It is also intriguing that the alliance–outcome association differed by informant but not by the specific client–therapist alliance (youth–therapist versus parent–therapist alliance) assessed. McLeod (2011) argued that the parent's perception of therapeutic alliance may be especially important for youth psychotherapy outcome because parents are the ones who seek treatment, consent to treatment, and physically bring the youth to treatment; moreover, youths may not be able to rate alliance as accurately as can adults due to their lower level of cognitive development (see our later section on this topic).

Even though the alliance-outcome association is small in youth psychotherapies, it is nevertheless reliably larger than zero. One potentially useful next step will be to test therapeutic alliance and other therapeutic relationship variables as mediators of treatment outcome in future youth psychotherapy studies.

Summary of Research on Mediators and Moderators of Evidence-Based Psychotherapies

To summarize the mediation evidence presented in the previous sections, mediators of EBPs for youths with depression, anxiety and phobic disorders, disruptive behavior problems, or substance abuse have been identified; a mediator of a medication-EBP combination treatment for ADHD has been identified; and no mediators of EBPs for youths with autism, eating disorders, OCD, or trauma have been identified, to our knowledge. Therapeutic alliance and relationship variables are promising candidates for future testing. Among the identified mediators, empirical support appears to be strongest for parenting skills and practices in the context of EBPs for disruptive behavior problems; evidence is also substantial for cognitive variables in the context of CBT for youth depression. More research will be needed to establish these mediators as true mechanisms of change (see our later section on this topic).

The evidence base on moderators of EBPs for youths is larger than that on mediators. Moderators were identified in relation to EBPs for every youth disorder except OCD (confirming significance tests are also needed for EBPs for trauma). A number of parent and family variables, including parent involvement in youth-focused treatments, youth involvement in parent-focused treatments, maternal EE, single- versus two-parent households, and parent versus youth as informant, emerged as moderators across several different disorders and treatment orientations.

Not surprisingly, a number of the findings on mediation and moderation concern family factors, a topic that warrants detailed attention in its own right. So, we focus now on the role of family factors in youth psychotherapy.

Family Factors in Youth Psychotherapy

As noted earlier, youth psychotherapy typically involves caregivers, and often other family members as well, and in a variety of roles—for example, referring the youth for treatment; identifying reasons for referral; providing information on the youth's current functioning and response to treatment; participating in the therapy; and collaborating in decisions about treatment content, structure, and termination. In some psychotherapy programs—such as Barkley's (1997) Defiant Children and Kazdin's (2010) Parent Management Training for disruptive, disobedient, and aggressive youngsters—caregivers are the primary participants in sessions with the therapist, learning skills to use with their children at home. In the context of such treatment programs, it is no surprise to find that parent–therapist alliance, like youth–therapist alliance, predicts treatment outcomes for young people (e.g., Kazdin, Whitley, & Marciano, 2006), and that youth outcomes are also predicted by the extent to which caregivers learn and use the new parenting skills therapy is designed to convey (Zisser & Eyberg, 2010). The full range of family factors relevant to youth psychotherapy is extensive and beyond the scope of this chapter (but see Chapter 15 in this volume for further elaboration). However, we offer here two examples of family factors that may warrant increased attention in future research.

Expressed Emotion

The home environment is a source of important protections from psychological distress and potential risk factors for poor psychological functioning. Of these risk factors, EE may be particularly relevant to the understanding of how psychological disorders develop and are maintained among both youths and adults. EE has been found to predict treatment outcome and relapse for a broad range of disorders (Hooley, 2007). Earlier in this chapter we noted the role of EE as a moderator of anorexia nervosa treatment effects (Eisler et al., 2000; Eisler et al., 2007). In addition, Asarnow, Goldstein, Tompson, and Guthrie (1993) found that youths with mood disorders were significantly more likely to maintain symptom reductions one year after inpatient treatment when returning home to live with a low rather than high EE mother. A correlation has been shown between critical EE and externalizing problems for children in first grade, and the critical EE of mothers of preschool children has been shown to longitudinally predict ADHD at grade three, even when accounting for both preschool behavior problems and maternal stress (Peris & Baker, 2000).

Although such findings are intriguing, further research is needed to clarify the association between EE and treatment process and outcome for children and adolescents. There has been considerable research on EE in children and adolescents, but questions remain regarding how the construct—originally developed for research on adult psychopathology—should be operationalized for youths. For example, McCarty and Weisz (2002) found that when using the Five Minute Speech Sample (FMSS; Magana et al., 1986) to assess EE, the emotional overinvolvement (EOI) facet has little connection to youth psychopathology, and positive comments made by the parent, which partially comprise EOI, have negative associations with youth psychopathology. These findings stand in direct conflict with predictions based on traditional conceptualization of EE, suggesting a need for a developmentally sensitive conceptualization of, and research on, EE. Consistent with traditional conceptualizations, however, McCarty and Weisz (2002) did find that critical EE was positively associated with symptoms of youth psychopathology.

Given that critical EE may well be the most important facet of EE for youth, based on research to date, it makes sense for future research to examine the role of perceived criticism (PC) in youth psychotherapy outcome and relapse. The study of EE within the adult literature naturally gave rise to the study of PC. Although critical expressed emotion is a measure of how much criticism is expressed by a relevant family member (e.g., a parent or a spouse) toward a specific patient or individual, it does not necessarily measure how much criticism “gets through” to the patient. Perceived criticism may be a better indicator of how much criticism gets through to a patient, and even of how much criticism is perceived regardless of the actual content or the intent of the speaker. Hooley and Teasdale (1989) found that perceived criticism, which is much easier to assess than EE, is a powerful predictor of treatment relapse in its own right, has strong test–retest reliability, and yields ratings independent of illness severity. As further research is done on these constructs, it will be useful to investigate the impact of criticism and perceived criticism in their own right, controlling for the patient behavior that may, in some cases, prompt the criticism (i.e., higher levels of criticism might, in some cases, reflect higher levels of youth psychopathology, which are linked to more of the behavior that parents and others find objectionable, and thus criticize). Level of parental criticism could in principle be studied as a possible moderator of treatment outcome and as a candidate mediator (i.e., improved youth functioning might be mediated in part by reductions in parental criticism). Despite evidence that EE is important for predicting outcome and relapse in both youths and adults and that PC is a powerful predictor of adult outcome, we know of no research examining PC in the context of youth psychotherapy.

The Challenge of Different Perspectives

Going beyond the attitudes and behavior of caregivers, we focus next on the fact that different family members differ from one another in their perception of events and behavior, and how these differences impact youth psychotherapy processes and outcomes. Informant discrepancies in the reports of various family members on youth behavior, functioning, and psychopathology have been among the most consistent findings in youth clinical research (Achenbach et al., 1987; De Los Reyes, Goodman, et al., 2010; De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005; Richters, 1992; Weisz & Weiss, 1991). As suggested by Weisz et al. (1997), the study of youth psychopathology “is inevitably the study of two phenomena: the behavior of the child, and the lens through which adults view child behavior” (p. 569). Different adults inevitably view the young person's behavior through different lenses, and these differ from the lenses used by the youth.

The complications associated with informant discrepancies are apparent in a variety of studies using community samples. For example, in a study of female caregiver–youth dyads, discrepant reports of parental monitoring predicted increased levels of youth-reported delinquent behaviors after a period of 2 years (De Los Reyes, Goodman, et al., 2010). In other community samples, disagreement between adolescents and parents has been shown to predict a variety of undesirable future outcomes, including drug abuse, police and judicial contact, expulsion from school, job loss, deliberate self-harm, and suicidal ideation/attempts (Ferdinand, van der Ende, & Verhulst, 2004, 2006).

Although some of these findings are open to multiple interpretations (e.g., youth–caregiver discrepancy might reflect youth–caregiver discord, parental inattention, or even success by the youth in concealing behavior), the associations with adverse outcomes do raise the question of whether caregiver–youth discrepancy has consequences for the process or outcome of psychotherapy. Clinicians who work with young people routinely face the challenge of determining the appropriate problems to address in therapy when youth and caregiver perspectives disagree. Prior studies have illustrated how challenging the task can be. In a sample of clinic-referred youths and their parents, Yeh and Weisz (2001) obtained information separately from the youths and their parents regarding what problems needed to be targeted in treatment. Some 63% of the youth-parent pairs failed to agree on a single specific target problem, and 36% failed to agree on even a single broad category (e.g., aggressive behavior, anxiety/depression). Extending these findings to include the perspectives of therapists, Hawley and Weisz (2003) found that 76% of parent-youth-therapist triads failed to agree on a single target problem and 44% failed to reach consensus on even one general problem category.

One common explanation for a lack of agreement between youths and parents in the treatment context is that discrepancies result in part from differing perspectives (Achenbach et al., 1987; Forehand, Frame, Wierson, Armistead, & Kempton, 1991). According to this view, externalizing problems are readily observable by parents whereas internalizing problems (e.g., worry or sad feelings) are less outwardly observable and thus more likely to be detected by the youth, who experiences the internalizing distress, than the parent. Consistent with this view, Weisz and Weiss (1991) provided evidence that externalizing problems were more commonly the basis of youth clinic referrals by parents than internalizing problems were. But as these authors noted, there are additional reasons why externalizing problems might be referred more often than internalizing problems (e.g., externalizing behavior is more disruptive at home and school and more likely to be distressing to others in the youth's world). An additional factor may be relevant: language fluency.

Disagreement as to what problems a youth has, or which problems warrant treatment, could affect treatment process and outcome. In a study of youth outpatient clinic treatment, Brookman-Frazee, Haine, Gabayan, and Garland (2008) found a positive association between caregiver–youth agreement on treatment goals, on the one hand, and number of sessions attended, on the other. In another study of outpatient treatment, level of caregiver–youth agreement in reports of youth psychopathology and interpersonal problems was positively associated with level of caregiver involvement in the treatment process (Israel, Thomsen, Langeveld, & Stormark, 2007). It will be useful, in future research, to explore the extent to which caregiver–youth agreement/disagreement is a predictor of treatment outcome, and also important to explore methods of reducing discrepancies before dropout occurs.

De Los Reyes, Alfano, and Beidel (2010a) have stressed the potential information value of informant discrepancies in psychotherapy. In a study investigating discordant reports among parent–youth dyads on measures of youth social phobia symptoms, parent-youth discrepancies at pretreatment significantly predicted discrepancies at posttreatment. This relation was found to be moderated by treatment responder status in that significant relations were found only for treatment non-responders. De Los Reyes, Alfano, et al. (2010) argued that this stability in measures of informant discrepancies across time suggests that discordant reports may serve as tools for evaluating youths' response to treatment. Repeated measures of caregiver-youth agreement during the course of therapy, these authors' believe, may shed light on how well youths are responding to treatment. Thus, informant discrepancies, rather than being “measurement error,” may provide information that can enrich our understanding of youth psychotherapy process and outcome (De Los Reyes, 2011; De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005).

Testing the Reach of Psychotherapies Across Population Groups

One way to test the strength and “reach” of youth EBPs is to examine the breadth of their impact across a range of population groups and risk conditions. We turn now to research addressing that agenda, with four groups of special interest.

Ethnic Minority Populations

The percentage of youths in the United States who are ethnic minorities was 43% in 2008, and this percentage continues to grow (Pollard & Mather, 2009). The prevalence of psychological disorders among ethnic minority groups in the United States is about the same as that of the general population (21%; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001), and the most recent statistics available suggest that about 13% of ethnic minority youths receive mental health services each year (Stagman & Cooper, 2010, estimate that 31% of European-American youths receive services). Although a large percentage of youths receiving mental health services belong to ethnic minority groups, some of the reports on treatment process and outcome for these youths have not been encouraging. For example, a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services document (DHHS, 2001) reported that only a small number of ethnic minorities had participated in psychotherapy RCTs, and that none of the studies had assessed the efficacy of the treatment by ethnicity or race. Chambless and colleagues (1996), in their review of treatments meeting EBP criteria, stated “We know of no psychotherapy treatment research that meets basic criteria important for demonstrating treatment efficacy for ethnic minority populations…” (Chambless et al., 1996). Additionally, some research had found ethnic minority youths more likely than European-Americans to drop out of treatment (Kazdin & Whitley, 2003) and significantly less likely to show clinical improvement when treated for depression (Weersing & Weisz, 2002a).