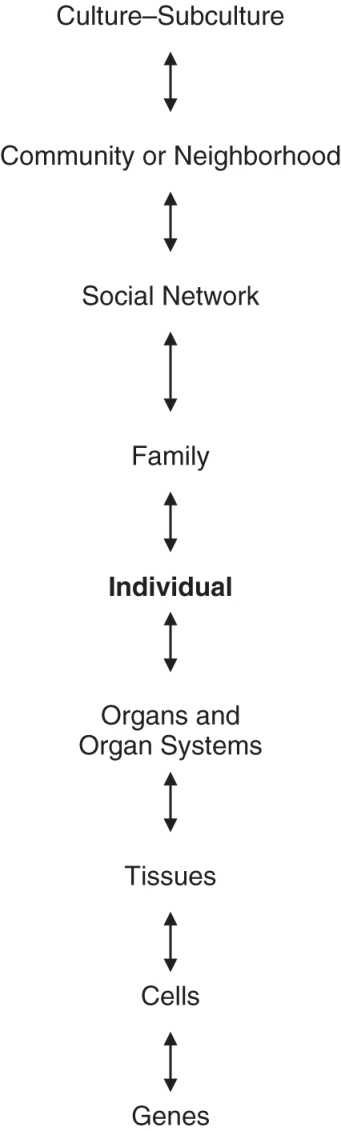

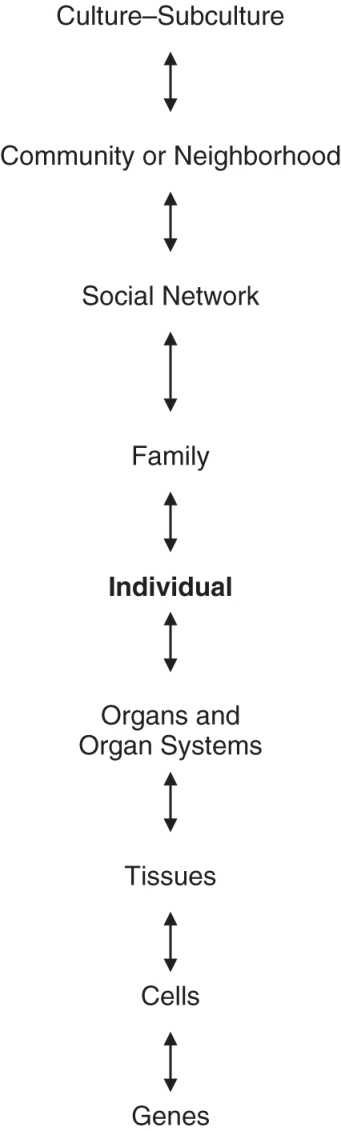

Figure 17.1 Systems hierarchy in the biopsychosocial model (based on Engel, 1977).

Since their formal beginnings in the 1970s, the related fields of behavioral medicine and health psychology have grown substantially and evolved. In many ways, their emergence was a necessary response to changing patterns of health. By the latter half of the 20th century, advances in public health and medicine (e.g., improved sanitation, hygiene, and nutrition; development of vaccines and antibiotics) had produced a dramatic reduction in morbidity and mortality from infectious disease in the United States and other industrialized nations, where previously they had been the leading causes of death. In these nations, infectious diseases were replaced by cardiovascular disease (e.g., coronary heart disease, stroke), cancer, chronic pulmonary disease, and diabetes as leading causes of death in adulthood.

These noncommunicable, chronic diseases differ from the previously predominant infectious diseases in several ways that involve major roles for behavioral science in biomedical research and health care (Fisher et al., 2011). Specific modifiable behaviors (e.g., smoking, high dietary intake of calories and fat, physical inactivity) strongly increase the risk for the initial development of these chronic conditions and influence their course, making behavioral processes key targets in prevention and treatment. Hence, the development of a scientific understanding of the determinants and modification of these behavioral risk factors has become a pressing priority. Also, these chronic diseases can have a profound impact on psychological and behavioral functioning or quality of life, broadly defined (e.g., emotional adjustment, social and vocational functioning, disability). As a result, management of these health outcomes and related effects of chronic disease (e.g., physical symptoms and distress) is an important component of efforts to reduce the burden of these conditions. Management of these consequences of chronic disease goes beyond biomedical treatments of the underlying physical condition, to include psychosocial approaches specifically targeting these emotional and behavioral outcomes, as adjuncts to traditional medical care. Finally, for several of these conditions, physiological effects of stress, negative emotion, and other psychosocial factors seem to play a direct role—independent of health behavior risk factors—in their development and course, creating a potential role for related psychological interventions in treatment of the underlying disease process.

The rapid expansion and evolution of health psychology and behavioral medicine is evident in the chapters on the topic appearing in prior versions of this handbook, and in the somewhat distinct focus of this, the fourth such chapter. Pomerleau and Rodin (1986) provided an overview of these still-emerging fields, focusing on areas of basic research (e.g., psychobiology of stress and disease) and applied research (e.g., adherence with medical regimens, coping with stressful medical procedures) that became important elements of the foundation of these fields. They also reviewed a smaller number of topics in emerging research on interventions (e.g., smoking cessation). Blanchard (1994) focused more specifically on intervention research, in which mostly individual and small group behavioral and cognitive-behavioral approaches targeted specific conditions (e.g., hypertension, chronic pain, insomnia) or risk factors for important diseases (e.g., obesity, smoking). This review provided clear evidence—from a rapidly growing number of increasingly methodologically rigorous intervention studies—that such treatments could produce clinically meaningful changes in risk factors, reduce the severity of several chronic medical conditions, and lessen their impact on functioning, making them useful additions to traditional approaches to medical care and prevention in many instances.

Creer, Holroyd, Glasgow, and Smith (2004) provided an updated review of many of these same intervention topics that included much additional evidence of clinically meaningful effects, but noted that the field had expanded so rapidly that a comprehensive review was no longer feasible. They also broadened their focus beyond the chronic diseases and conditions in industrialized nations to include more global or world health issues, such as the burden of infectious diseases (i.e., HIV, tuberculosis) in less developed nations. This global focus made clear that much of the potential impact of behavioral medicine and health psychology lies in their role in public health, policy, and various population-level interventions, as well as the more traditional individual and small group-level approaches.

In this chapter, after a brief overview of the conceptual foundations of these closely related fields we, too, provide a necessarily condensed and selective update of the empirical status of intervention research and applications in behavioral medicine and health psychology, focusing almost exclusively on adults. As a guide to a more thorough coverage of the field for interested readers, we cite qualitative and quantitative reviews of many specific topics. Consistent with the overall focus of the handbook, we primarily review intervention issues, covering other topics to the extent that they are needed to appreciate the current state and future directions of these fields. Although we heartily endorse the view of Creer and colleagues (2004) that health psychology and behavioral medicine have much to offer efforts to address the burdens of infectious illness in developing and less industrialized nations of the world, we focus primarily on intervention issues in the United States and other industrialized countries. However, it is important to note that 60% of deaths worldwide are due to noncommunicable chronic diseases, and 80% of those deaths occur in the developing world (Alwan et al., 2010). Hence, the issues we address are highly relevant in both industrialized and developing nations. Further, as we discuss in closing, in the coming years the health agendas in industrialized and developing nations are expected to converge further, and we discuss the implications of these trends for health psychology and behavioral medicine.

Given the primary focus of this handbook on services delivered to individuals and small groups, we emphasize similar approaches to the modification of health relevant behavior and the treatment or management of chronic disease, as opposed to more broadly focused large-group, population-level, policy, or public health intervention approaches. Hence, in a departure from prior editions of the handbook, our chapter title specifically refers to behavioral medicine and clinical health psychology, to designate our greater focus on the delivery of psychological services in medical settings and psychological consultation or collaboration with traditional health care providers. The rapidly evolving nature of medical care in the United States and other industrialized nations poses both major opportunities and daunting challenges for these central aspects of behavioral medicine and clinical health psychology.

However, just as the psychotherapy and behavior change research community has increasingly recognized the need to expand the portfolio of mental health services beyond traditional interventions for emotional distress and disorders delivered to individuals and small groups to include more population-based, preventive, and public health strategies (Kazdin & Blase, 2011), we also discuss the larger-group and population-based approaches that are a central focus in more broadly defined behavioral medicine and health psychology. These aspects of behavioral medicine and health psychology face an equally far-reaching set of opportunities and challenges. Indeed, these two trends in the field—refinement of individual and small group approaches and their integration into evolving models of medical care, and the development and dissemination of more large-group and population-focused strategies primarily addressing health behavior change—represent an evolving distinction within these fields. These two segments of behavioral medicine and health psychology involve different training requirements (e.g., traditional psychological approaches, transposed to health care settings and medical populations versus organizational, community, policy, and public health approaches to behavior change) and sets of likely collaborators (e.g., primary medical care providers and medical specialists versus health educators, practitioners in community and public health, policy makers).

The terms health psychology and behavioral medicine are sometimes distinguished quite carefully (Pomerleau & Rodin, 1986), and at other times are used interchangeably (Creer et al., 2004). Initially, the two fields were distinguished in part by a more explicit inclusion of biomedical science and clinical medicine within the description of behavioral medicine. Also, early in its emergence, behavioral medicine was more closely based in operant and classical learning theory approaches to psychological aspects of the development and management of disease (Pomerleau & Brady, 1979; Surwit, Williams, & Shapiro, 1982). That is, behavioral medicine was explicitly associated with behaviorism in early definitions, in part to distinguish it from the psychoanalytic perspective that had previously characterized one of its main historical predecessors—psychosomatic medicine. In contrast, health psychology reflected a broader array of conceptual perspectives on psychological processes, based in social, clinical, developmental, experimental, physiological, and personality psychology (Stone, Cohen, & Adler, 1979). Soon, behavioral medicine also came to include a greater variety of conceptual approaches and traditions regarding the behavioral, psychological, and social-environmental aspects of disease (Gentry, 1984), as did psychosomatic medicine (cf. Novak et al., 2007).

Currently, both behavioral medicine and health psychology involve the development and integration of behavioral, psychosocial, and biomedical research in an effort to understand health and illness, and the application of the resulting knowledge in efforts to prevent and treat physical illness. The distinction between health psychology and behavioral medicine now lies mostly in matters of professional identify and training, rather than their overall mission or conceptual orientation. Health psychology is conducted largely—but not exclusively—by psychologists, whereas behavioral medicine involves a greater variety of professionals, including psychologists, physicians, epidemiologists, sociologists, nurses, and others. In this way, behavioral medicine is the broader, more inclusive field, of which health psychology is a subfield. Clinical health psychology, in turn, is the subfield within health psychology that involves research and applied services regarding the prevention, management, and treatment of physical illness. Whereas health psychology broadly defined includes large-group and population-based approaches to prevention and health behavior change, clinical health psychology focuses more specifically on applications with individuals and small groups, often for those with well-established unhealthy behavior or existing physical illness or other medical conditions.

Both health psychology and behavioral medicine comprise three general, interrelated topics. Stress and disease—or psychosomatics—is perhaps the oldest, and concerns the direct psychobiological effects of stress, negative emotion, and related processes on the pathophysiology of disease. Within this topic, researchers examine the associations of psychosocial risk factors (e.g., social isolation, job stress, chronic anger, depression) with the development and course of disease (Everson-Rose & Clark, 2010). Other studies examine the physiological mechanisms (e.g., alterations in neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, or immune system responses) that link psychosocial inputs and disease outcomes (Lovallo, 2010). Animal studies of this topic manipulate levels of environmental stress in ways that are not possible with human participants to examine effects on disease processes and underlying physiological mechanisms (Nation, Schneiderman, & McCabe, 2010). Results of such efforts guide the development and evaluation of interventions that target stress, negative emotion, and related factors in order to alter the development and course of disease (Schneiderman, Antoni, Penedo, & Ironson, 2010).

The second major topic—health behavior and prevention—examines the association of daily habits (e.g., smoking, diet, physical activity) with the development and course of disease (Kaplan, 2010), as well as the determinants of these behaviors (Schwarzer, 2011). This information then guides the development, evaluation, and implementation of interventions intended to promote healthier lifestyles. The third topic—psychosocial aspects of medical illness and medical care—examines the impact of physical illness and related medical care on a variety of aspects of functioning, including emotional adjustment, physical distress, social and vocational roles, and general levels of functional activity versus disability (Stanton, Revenson, & Tennen, 2007). This general topic also includes behavioral aspects of medical treatment (e.g., adherence with medical regimens), and the process of health care utilization (e.g., patient-provider communication, seeking health services; Baldwin, Kellerman, & Christensen, 2010). Research in this third area guides the development, evaluation, and implementation of adjunctive psychological and behavioral treatments for medical conditions (Schneiderman et al., 2010).

These topics are clearly overlapping. For example, exercise may be prescribed for recovering heart patients not only because of its direct physiological effects in reducing the risk of recurrent coronary events, but also because exercise is sometimes useful both in managing the depressive symptoms that often accompany coronary disease and in helping the patients to return to work and prior levels of functional activity (Stein, 2012). Across all three topics, treatment research of various types tests the efficacy and effectiveness of the resulting interventions as potential additions to standard medical and surgical approaches to prevention and disease management (Oldenburg, Absetz, & Chan, 2010).

Since their inception, health psychology and behavioral medicine have been strongly tied to the biopsychosocial model (Suls, Luger, & Martin, 2010). Traditional medicine is based on the biomedical model of disease, in which biological processes are seen as providing a sufficient basis for understanding, treating, and preventing disease. The success of this model is readily apparent in dramatic improvements in health and advances in medical treatment over the last century. Yet, many authors over many decades have deemed the biomedical approach to be incomplete, given its neglect of the role of psychological, social, and cultural factors in disease etiology and medical treatment (Suls et al., 2010). As a response to these perceived limitations, Engel (1977) proposed the biopsychosocial model (see Figure 17.1). Rather than reducing disease to basic biological causes and focusing only on biologically based treatments, the biopsychosocial model describes health and illness as the result of reciprocal influences among hierarchically arranged levels of analysis (von Bertalanffy, 1968). These levels range from the lower or more basic levels of the traditional biomedical model (i.e., biochemical processes, genes, cells, tissues, and organ systems) to the level of the behaving individual and on to higher levels of interpersonal, social, and broader environmental and cultural levels. In traditional scientific approaches, each level of analysis is understood through its own models and methods. However, in the biopsychosocial framework, each system or level influences and is influenced by the adjacent levels. In this view, any specific disease process (e.g., atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries) cannot be fully understood through a given level of analysis (e.g., molecular biology of inflammation; tissue pathology). It also must be considered at the multiple levels above and below in the hierarchy.

Figure 17.1 Systems hierarchy in the biopsychosocial model (based on Engel, 1977).

The implications for research, medical care, and the prevention of disease are clear. To understand the contributing factors for any given disease or medical condition, multilevel, integrative research is needed. Similarly, for an optimal approach to prevention, treatment, and management, opportunities at multiple levels must be explored. In discussing the applied implications of his model for clinical care, Engel (1980) suggested that “while the bench scientist can with relative impunity single out and isolate for sequential study components of an organized whole, the physician does so at the risk of neglect of, if not injury to, the object of study” (p. 536). Hence, the biopsychosocial model directs health care providers toward a multilevel, integrative approach to the evaluation and treatment of individual patients.

This framework also clearly suggests that regardless of whether they are biological or behavioral in focus, individual-based approaches to a given medical problem are incomplete; they should be augmented by broader social, organizational, community, and cultural level strategies for prevention and management. Leading causes of death (e.g., cardiovascular disease, cancer) will be best understood, prevented, and managed if each of these levels of analysis are considered and addressed. Although it is typically not feasible to address all levels of analysis in providing care to individual patients, a comprehensive medical, public health, and policy approach to the challenges posed by any given disease must consider the full range of levels of analysis. Consideration of these multiple levels also makes clear that a comprehensive, biopsychosocial model includes not only treatment of existing disease, but the prevention and reduction of disease risk well before its clinical onset.

As described previously, the behavioral perspective was the main psychological conceptual view during the formative years of behavioral medicine (Pomerleau & Brady, 1979; Surwit et al., 1982), and remains an important, but less dominant perspective today. Many interventions currently in use in the field are based on operant and classical learning models, both in prevention efforts and in the management of chronic illness and other medical problems. Paralleling trends in clinical psychology, behavioral medicine soon incorporated the cognitive-behavioral perspective (Wilson, 1980), most notably social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) and related perspectives emerging in the 1970s (Beck, 1976; Mahoney, 1977; Meichenbaum, 1977).

A major influence in all areas of health psychology and behavioral medicine has been the stress and coping model developed by Lazarus and his colleagues (Cohen & Lazarus, 1979; Lazarus, 1966; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Articulation of the role in stress of primary appraisal (i.e., judgments about potential for threat, harm, or loss) and secondary appraisal (i.e., judgments about opportunities for preventing or moderating the potential negative outcome) and emotion-focused coping (i.e., efforts to reduce the negative affect in response to stress) and problem-focused coping (i.e., efforts to reduce the demands of the stressor) produced a clear set of testable hypotheses and potential targets for interventions for stress-related problems. Given that stress plays a central role in all three of the major issues or topics in behavioral medicine and health psychology described previously (i.e., health behavior and prevention, stress and disease, psychosocial aspects of medical illness and medical care), this general perspective is a cornerstone in the foundation of these fields. The cognitive-behavioral perspective provided an important extension of the stress and coping paradigm, in describing an array of interventions easily adapted to focus on modification of the key concepts of appraisal and coping.

Personality characteristics are increasingly recognized as important influences on stress and disease, health behavior, and the impact of medical illness and aspects of medical care on emotional adjustment and functional activity (Smith, 2006a). For example, personality characteristics influence exposure to various sources of stress (e.g., interpersonal conflict), the magnitude of emotional and physiological stress responses, emotional and physiological recovery after stress exposure, and stress-related restorative processes (e.g., sleep quality; Williams, Smith, Gunn, & Uchino, 2011). Current theory and research in behavioral medicine and health psychology utilizes traditional trait approaches to personality, as well as social-cognitive and interpersonal perspectives to address these issues. Social psychological perspectives on individual behavior are also prominent, especially those perspectives that emphasize individuals' attitudes and beliefs about health relevant behavior (Kiviniemi & Rothman, 2010) and internal representations or “cognitive models” of the nature of specific medical conditions and related treatments (Leventhal, Breland, Mora, & Leventhal, 2010).

In each of the three main research topics in behavioral medicine and health psychology, social relationships are a central consideration. The availability and quality of personal relationships (i.e., social support and integration versus isolation) is an important predictor of the development and course of serious disease (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010; Lett et al., 2005), and a variety of psychobiological mechanisms have been identified as potentially underlying such associations (Uchino, 2006). The quality of marriage and similar close relationships is a similarly important influence on the development and course of disease (e.g., De Vogli, Chandola, & Marmot, 2007; Rohrbaugh, Shoham, & Coyne, 2006; Smith, Uchino, Berg, & Florsheim, 2012), and on adaptation to chronic medical conditions (Hagedoorn, Sanderman, Bolks, Tuinstra, & Coyne, 2008; Leonard, Cano, & Johansen, 2006). Couple-based interventions have been found to be useful in addressing a variety of behavioral risk reduction efforts and the management of several chronic diseases (Martire, Schulz, Helgeson, Small, & Saghafi, 2010; Shields, Finley, Chawla, & Meadows, 2012).

Broader features or levels of social context are an important component of the biopsychosocial model. For example, effective health behavior change programs have been developed for delivery in schools (Katz, 2009), worksites (Goetzel & Ozminkowski, 2008), and churches (Campbell et al., 2007). Characteristics of neighborhoods and the built environment (e.g., socioeconomic level, cohesion, safety, “walk-ability” and conduciveness to physical activity) have robust influences on health (Diez-Roux & Mair, 2010). Socioeconomic status (SES) has a strong, inverse relationship with the development and course of virtually all major causes of morbidity and mortality (Matthews & Gallo, 2010). Low SES is also associated with smaller declines in major causes of morbidity and mortality in recent years, due primarily to slower decreases in behavioral risks, less access to effective procedures for early detection, and less access to improved treatments (Byers, 2010). Public policy and environmental-level interventions (e.g., prohibition on smoking in public places) can clearly have effects on health behavior and the development and course of chronic disease (Brownson, Haire-Joshu, & Luke, 2006; Fisher et al., 2010). Hence, multiple levels of social—environmental context are the focus of current research and interventions in behavioral medicine and health psychology.

In recent years, behavioral medicine and health psychology have responded to the growing influence of the evidence based medicine movement (Spring et al., 2005), which calls for the development and use of a sound research base as a guide to medical care (Sackett, Rosenberg, Gray, Haynes, & Richardson, 1996). In this perspective, a hierarchy of evidence informs clinical practice, with randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews of multiple RCTs as the top two tiers of evidence. This has involved adopting accepted, rigorous standards for conducting and reporting both RCTs (Altman et al., 2001) and systematic reviews of literatures where multiple trials have been conducted (Higgins & Green, 2011). Many previous RCTs in behavioral medicine and health psychology had been designed, analyzed, and/or reported in ways that fell short of these commendable, more recent standards (Davidson et al., 2003; Davidson, Trudeau, Ockene, Orleans, & Kalpan, 2004; Spring, Pagato, Knatterud, Kozak, & Hedeker, 2007), as had many systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Coyne, Thombs, & Hagendoorn, 2010). As a result, the impact of much of the prior intervention research in the field has been reduced somewhat by this recent history of new and rising methodological standards. At the same time, issues surrounding appropriate endpoints or health outcomes for intervention research have been also been evolving in important ways.

In some cases, behavioral endpoints (e.g., smoking cessation, physical activity levels) have always been straightforward in intervention research, as have some intermediate biologic endpoints (e.g., weight loss, blood pressure reductions), although the methods used to measure the endpoints and draw conclusions about the clinical implications of observed treatment effects have been a matter of considerable discussion (Smith, 2011). However, because traditional medical research typically emphasizes objective indicators of disease-specific morbidity and mortality (i.e., evidence of myocardial infarction in ECG changes and cardiac enzyme elevations; survivorship in advanced cancer) in evaluating medical and surgical interventions, demonstrations of effects of behavioral interventions on these “hard” medical outcomes has been an important source of evidence in the field. Indeed, the field as a whole has periodically been criticized by traditional medical researchers for the lack of consistent effects of psychological intervention on these endpoints (Relman & Angell, 2002).

Although objectively assessed morbidity and mortality continue to be outcomes of paramount importance in intervention research, medical research and policy as a whole has expanded to emphasize a broader view of health outcomes. Specifically, emerging definitions of health include behavioral and subjective endpoints. Levels of functional activity versus disability, physical symptoms (e.g., pain, fatigue), emotional adjustment, and social functioning in personal relationships and vocational or academic roles have long been important outcomes in behavioral medicine and health psychology intervention research. But interest in these behavioral outcomes and subjective reports has been increasing in recent years in the biomedical and health care research community.

For example, in 2004 the National Institutes of Health established the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS; www.nihpromis.org), and expanded the program in 2010. The goal of this initiative is the development and dissemination of patient-reported measures of physical, mental, and social well-being. Traditional measurement issues (i.e., reliability, validity) are a major focus of current and planned PROMIS research, but the mission is broader. One goal is to develop measures that provide standardized, comparable information across a variety of domains and medical conditions. Flexibility in measurement use and applicability to a wide range of demographic groups is also a major focus. In this way the impact of a variety of medical conditions can be compared, as can variations in their impact across segments of the population. Importantly, standardized and broadly applicable measures will facilitate more precise, integrated, and comparative evaluations of a wide variety of interventions.

The increased emphasis on patient reported outcomes is also evident in the recently established Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (P-CORI: www.pcori.org). This independent, nonprofit institute was established by the United States Congress in 2010, through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Its mission is to develop and disseminate information to inform health care decisions, specifically information based on empirical evidence about the effectiveness, benefits, and harms of treatment options patients and providers are considering, and the ways in which those outcomes differ for specific types of patients. In addition to information about survival or longevity and other objective biomedical outcomes for morbidity in various conditions (e.g., blood pressure, plasma lipid levels, blood glucose levels), the P-CORI mission specifically includes patient functioning (i.e., activity versus disability), symptoms, and health-related quality of life (H-QOL). Hence, classes of outcomes that have historically been seen as “soft” and providing weak evidence regarding the effects of interventions in behavioral medicine and health psychology are increasingly seen as important—for evaluations of clinical efficacy and effectiveness, for patients and providers choosing among treatment options, and as a guide to policy decisions regarding health care spending.

Outcomes that capture morbidity, mortality, and H-QOL have an important role not only in evaluating the effects of specific interventions, but also in comparing the relative benefits of various interventions. An increasingly common outcome index is the quality adjusted life year (QALY), which essentially weights each year of life by the H-QOL during that year (Kaplan & Groessl, 2002). QALYs can be used to compare not only a variety of intervention outcomes, but also can evaluate their cost-effectiveness by quantifying the cost associated with each QALY produced by that intervention (Kaplan & Groessl, 2002). It is possible that this growing emphasis on broader assessments of health outcomes will make the value of interventions in behavioral medicine and health psychology more apparent. They have the potential to influence not only mortality, but also directly improve components of H-QOL and do so at relatively low cost.

In addition to efforts to implement new standards for design, analysis, and reporting of RCTs, the choice of appropriate comparison or control conditions has received increased attention in behavioral medicine and clinical health psychology intervention research (Freedland, Mohr, Davidson, & Schwartz, 2011). The magnitude and meaning of the observed intervention effect depend, in large part, on the nature of the comparison or control conditions, and different comparison conditions are appropriate for specific questions. For example, comparisons to usual medical or surgical care are often used in initial evaluations of the efficacy of an adjunctive behavioral or psychological intervention, but can be faulted for failure to control for expectancies and other nonspecific factors. Variations in comparison conditions across multiple RCTs evaluating a given intervention can complicate systematic reviews and meta-analyses, the highest form of evidence in the EBM perspective.

Relative to prior reviews of the efficacy of interventions in behavioral medicine and health psychology (e.g., Blanchard, 1994), it is clear that methodological standards for the RCTs have been raised. However, facilitating an expansion of the research base demonstrating efficacy is not the only challenge for current intervention research. Enhancing the external validity of intervention trials and producing stronger evidence of effectiveness of interventions in representative health care settings is an increasingly important concern (Glasgow, 2008; Glasgow & Emmons, 2007).

In terms of impact on population health, intervention efficacy and effectiveness are critical concerns, but so is the number of individuals reached by a given intervention (Abrams et al., 1996). Even a highly efficacious intervention will have limited impact on population health if high costs or restricted access means it reaches a limited number of people who might otherwise benefit. Conversely, an intervention with relatively modest efficacy (i.e., a small treatment effect size) can have a substantial impact on population health if it reaches a very large portion of that population. This concept has been expanded in the RE-AIM (Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) framework of Glasgow and colleagues, which has been applied to both prevention-oriented health behavior change interventions (Glasgow, Vogt, & Boles, 1999) and chronic illness management (Glasgow, McKay, Piette, & Reynolds, 2001). In this expanded perspective (see Table 17.1), the health impact of a given intervention is the product of its reach and efficacy (i.e., Impact = Reach × Efficacy), but other critical determinants of health impact are the extent to which the intervention is adopted in health services, the consistency and fidelity with which it is implemented in those settings, and the maintenance of that implementation. The RE-AIM model defines the important issue of intervention effectiveness as Efficacy × Implementation.

Table 17.1 The RE-AIM Framework (Glasgow, Vogt, & Boles, 1999). Tables can be downloaded in PDF formats at http://higheredbcs.wiley.com/legacy/college/lambert/1118038207/pdf/c17_t01.pdf.

| Reach | Proportion of the target population participating in the intervention |

| Efficacy | Success rate if intervention is implemented as intended in guidelines |

| Adoption | Proportion of settings, practices, and health care plans adopting the intervention |

| Implementation | Extent to which intervention is implemented as intended in real-world settings |

| Maintenance | Extent to which intervention program is sustained over time |

From this perspective, some issues in maximizing the potential health impact of behavioral medicine and health psychology interventions are largely new topics for research. Specifically the process of dissemination of research findings from RCTs of intervention efficacy, effectiveness studies, and systematic reviews, and the processes of intervention adoption and implementation are increasingly the focus of research in their own right (Kerner, Rimer, & Emmons, 2005; McHugh & Barlow, 2011). This emerging focus on translational science in the field recognizes that, “the behaviors in need of change are not just those of our patients, but also those of our main professional partners” including health care providers and policy makers (Spring, 2011, p. 1).

Smoking, levels of physical activity and fitness, dietary intake of calories and fat, and related levels of adiposity (i.e., overweight) are strongly related—individually and in combination—to cardiovascular disease (CVD) morbidity and mortality, cancer morbidity and mortality, diabetes, and all-cause mortality (Lee, Sui, Artero, et al., 2011; Lee, Sui, & Blair, 2009; Lee, Sui, Hooker, Herbert, & Blair, 2011). A substantial proportion of the decreases in morbidity and mortality associated with CVD and cancer in recent decades are attributable to population decreases in unhealthy behaviors (Byers, 2010; Ford & Capewell, 2011). Despite this progress, some estimates suggest that approximately 80% of CVD and diabetes, and 40% of cancers are still due to poor diet, physical inactivity, and tobacco use (Fisher et al., 2011; Spring, 2011). Further, has been suggested that type 2 diabetes could be largely eliminated through population-based changes in excess adiposity, moderate diet, and physical activity (Schulz & Hu, 2005). Yet in the United States spending on related prevention efforts is 5% or less of total health care expenditures (McGinnis, Williams-Russo, & Knickman, 2002; Satcher, 2006). Relative to the costs of treating these chronic health conditions, efforts to prevent them through the modification of related behaviors are highly cost-effective (Gordon, Graves, Hawkes, & Eaken, 2007).

Prominent models conceptualize health behavior change as a multiphase process, in which different points in the change process pose distinct challenges and require distinct intervention elements. This view is most formally represented in the Stages of Change Model, also known as the Trans-Theoretical Model (SOC/TTM; J. O. Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992). In this view, individuals pass sequentially through precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance stages, perhaps multiple times in the event of relapse and renewed change attempts. In theory, different types of interventions are effective at different stages, creating a stage-by-intervention-type matching prediction regarding optimal change; interventions tailored or matched to the individual's specific location along the multistage process will be more effective than unmatched interventions. This tailoring or matching prediction has been supported in some research (Johnson et al., 2008; Krebs, Prochaska, & Rossi, 2010), as have other elements of the model (Hall & Rossi, 2008). However, the stages are often difficult to distinguish empirically (Herzog, 2008; Weinstein, Rothman, & Sutton, 1998), and matched or tailored interventions are often no more effective—or only slightly more effective—than nonmatched interventions (Armitage, 2009; Noar, Benac, & Harris, 2007).

The earliest point in the process of health behavior change is the primary focus of another influential model and related technique—motivational interviewing (Miller & Rose, 2009). This approach to patient interviews regarding potential health behavior change involves empathy, acceptance, and collaboration rather than the directive and problem-focused style that characterizes most medical encounters. The motivational interviewing (MI) approach also attempts to evoke and reinforce the patient's spontaneous and self-initiated “change talk.” Motivational interviewing is often implemented in brief contacts with patients in primary medical care, and has been found to have positive effects on efforts to modify smoking, diet, exercise, and the control of chronic disease (e.g., diabetes) (Lundahl & Burke, 2009; Martin & McNeil, 2009). However, RCTs on motivational interviewing have been criticized as methodologically limited, and producing small effect sizes (Knight, McGowan, Dickens, & Bundy, 2006). Many health behavior change attempts result in initial success but subsequent failure (Brandon, Vidrine, & Litvin, 2007), leading to the common practice of incorporating relapse prevention training as a component of interventions (Hendershot, Witkiewitz, George, & Marlatt, 2011). The approach is understandably widely used, but it has been difficult to demonstrate its independent efficacy (Agboola, McNeill, Coleman, & Bee, 2010).

Finally, in an effort to maximize health impact while minimizing costs, stepped care approaches have been developed in which low cost, largely self-guided health behavior change interventions are attempted initially, reserving professionally—delivered small group and individual treatments for cases where the less involved and costly “steps” fail to produce desired results (Abrams et al., 1996). The initial, low intensity and low cost steps have greater reach (Glasgow et al., 1999), and therefore have the potential to have important population impact. The higher efficacy but more intensive and costly approaches can be reserved for individuals who experience difficulty achieving or maintaining desired changes. Large group, organizational, and public policy interventions have the greatest potential reach. Given the remarkable prevalence of nearly all of the major behavioral risk factors, these approaches are a major focus of more broadly defined behavioral medicine and health psychology.

After decades of steady reductions in the prevalence of smoking in the United States and some other industrialized nations, this progress has slowed in recent years. Currently, approximately 20% of adults in the United States smoke, and this behavior remains the leading cause of preventable death. The most common reason for attempting to quit smoking is a concern about health (McCaul et al., 2006), and for smokers there is no other behavior change that will provide as great a potential health benefit. Yet, most cessation attempts result in failure. Hence, smoking cessation is a major challenge in current behavioral medicine and clinical health psychology.

For individual and small-group based approaches to smoking cessation, the major treatments currently in use are multicomponent interventions, often combining pharmacologic and behavioral interventions. Major meta-analyses indicate that CBT for smoking cessation (e.g., problem solving, skills training, stress management) is modestly effective, producing a 40% to 60% increase in the odds of maintained cessation (Fiore et al., 2008; Lancaster & Stead, 2005). However, it is important to note that given that as many as 90% or more of unaided quit attempts result in failure within 6 to 12 months, even in the most successful interventions the majority of smokers relapse within the typical follow-up periods. Given the design of the individual trials, it is difficult to identify the most effective elements of CBT. In most of the individual RCTs the experimental control of nonspecific factors is minimal. To address these limitations, RCTs are needed to test specific components and packages, while controlling nonspecific factors and evaluating hypotheses regarding the mechanisms contributing to change (Bricker, 2010).

Meta-analytic reviews and major RCTs have demonstrated the efficacy of nicotine replacement therapy in both longer-acting (e.g., nicotine patches) and shorter-acting (e.g., nicotine gum) forms, and the efficacy of buproprion (i.e., Zyban, Wellbutron) and varenicline (i.e., Chantix) (Baker et al., 2011; Fiore et al., 2008; Fiore & Baker, 2011; Stead, Perera, Bullen, Mant, & Lancaster, 2008). These pharmacological treatments provide improved outcomes over CBT alone, and hence the combination of CBT or similar counseling approaches with pharmacological treatment is currently considered the standard of care (Fiore et al., 2008), although even the strongest effects of medication demonstrated in these reviews indicate that most treated smokers do not maintain cessation. It is possible that pharmacologic treatment may be even more effective if initiated well before the smoker's “quit date” (Baker et al., 2011).

Many smokers have considered smoking cessation but have not made a serious attempt to quit, or have failed in previous attempts. As a result, at any given time a large number of smokers are characterized by a low level of motivation for cessation. Motivational interviewing would seem to be a useful approach in this scenario, but to date there is little evidence that it produces a significant, independent effect on cessation (Bricker, 2010; Hettema, Steele, & Miller, 2005). Given that many smokers relapse after an initially successful quit attempt, relapse prevention is a common element of CBT approaches to smoking cessation. However, the evidence from RCTs specifically evaluating the effects of relapse prevention training indicates that it has little or no additional benefit (Lancaster, Hajek, Stead, West, & Jarvis, 2006). Research on the SOC/TTM approach in which specific interventions are matched to the smoker's stage along the continuum of change described previously has produced evidence of small improvements in cessation and abstinence (Noar et al., 2007), but some RCTs based on the model have not found evidence of the predicted benefits of matching (e.g., Aveyard, Massey, Parsons, Manasecki, & Griffin, 2009). This pattern of findings has led to the conclusion that the model is largely unsupported in this important health behavior domain (e.g., Bricker, 2010; West, 2005).

Despite the limited evidence in support of the SOC/TTM predictions regarding the effects of matching specific interventions to phases of the change process on smoking cessation and abstinence, it is clear that different sets of multifaceted challenges are prominent at different points in the smoking cessation process—motivating smokers to seriously consider quitting, preparing for cessation, the actual process of cessation, and maintaining abstinence and managing brief lapses and more prolonged relapses. Further, it is apparent that within each of these phases, the multiple challenges likely require multiple intervention approaches (Baker et al., 2011). Thus, process approaches warrant additional research, though perhaps should be expanded beyond the traditional stages of change framework. However, even in the absence of clear and specific evidence from RCTs, the current status of the evidence on the psychobiology of nicotine dependence and addiction and related behavioral research on addictive behavior suggests that it is appropriate to select and combine approaches to address these specific sets of challenges (Baker et al., 2011). Hence, this emerging expansion of the standard of care recognizes the value of combined pharmacologic and CBT treatments that should also reflect the differing challenges at various points in the process of smoking cessation.

Several environmental and policy-level approaches to smoking have been found effective in reducing smoking and lowering related health care costs, including raising taxes on tobacco, reducing smoke exposure (i.e., “secondhand” smoke) by prohibiting smoking in public places, bans on tobacco advertising and sponsorships, regulation of packaging and warning labels, promoting public awareness, increasing access to smoking cessation through expanded insurance coverage and public funding, and decreasing tobacco sales to minors through increased penalties for illegal sales (Cummings, Fong, & Borland, 2009). Policy-based changes in health care systems have also been found to be effective, including improved tracking of smoking status in health records, and increasing health care professionals' frequency and consistency of asking about smoking status and providing encouragement to quit (Curry, Keller, Orleans, & Fiore, 2008). Specific guidelines have been developed for health care providers for addressing smoking among their patients (Fiore & Baker, 2011). These guidelines involve regular inquires about the patient's smoking status and readiness to pursue smoking cessation, motivational interventions for those low in readiness, and specific pharmacological and behavioral interventions for those smoking patients who are ready to proceed.

Obesity defined as a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30 kg/m2 has been associated with a host of negative health outcomes including coronary heart disease (Bogers et al., 2007), type 2 diabetes (Guh et al., 2009), some forms of cancer (Renehan, Tyson, Egger, Heller, & Zwahlen, 2008), and mortality related to these and other conditions (Whitlock et al., 2009). Importantly, recent prevalence estimates indicate that more than 30% of adults are obese (Flegal, Carroll, Ogden, & Curtin, 2010). Prevalence rates have more than doubled since the late 1970s, and even though this dramatic increase has slowed in recent years for children, adolescents, and adults (Flegal, Carroll, Kit, & Ogden, 2012; Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2012), medical experts now consider obesity to be “epidemic” (Stein & Colditz, 2004). Not surprisingly then, behavioral approaches to weight loss continue to be a major focus of clinical health psychology and behavioral medicine.

A recent review of behavioral treatments for obesity concluded that, on average, intervention studies report a 10% decrease in body weight—enough for improvements in health—but that maintaining weight loss continues to be challenging (Butryn, Webb, & Wadden, 2011). Using in-person, Internet, or telephone contact between patients and providers to prolong engagement in interventions, encouraging high amounts of physical activity, or combining lifestyle behavior change with pharmacotherapy have shown promise in preventing weight regain (Butryn et al., 2011). For example, a recent randomized controlled trial demonstrated the efficacy of combined naltrexone/bupropion therapy as an adjunct to intensive behavior modification for obesity, with the drug intervention producing a 9% reduction in body weight compared to 5% among controls (Wadden et al., 2011). In another recent RCT, two behavioral interventions, one delivered with in-person support and the other delivered remotely, without face-to-face contact between participants and weight-loss coaches, resulted in clinically significant weight loss averaging more than 10 pounds over a period of 24 months, compared to only approximately 2 pounds in a comparison group (Appel et al., 2011). Other RCTs of web-based intervention have found that greater weight loss is observed among those with higher levels of website utilization (Bennett et al., 2010). Another recent RCT examined the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a cognitive-behavioral weight management program in the form of written materials and basic web access, complemented by an interactive website and brief telephone/email coaching. Participants (1,755 overweight) were randomized to one of three conditions with increasing intervention intensity. Participants experienced significant weight loss, increased physical activity, and decreased blood pressure across conditions. Cost-effectiveness ratios were $900 to $1,100/quality-adjusted life year for the two lower intensity interventions and $1,900/quality-adjusted life year for the higher intensity intervention (web intervention plus coaching). The cost recovery analyses indicated that the costs of treatment were matched by savings in health care expenditures after 3 years for the two lower intensity interventions and after 6 years for the other intervention (Hersey et al., 2012). A recent meta-analysis indicated that the addition of motivational interviewing to weight loss intervention resulted in a small (3 pounds) additional weight loss in obese and overweight individuals (Armstrong et al., 2011). Collectively, these studies highlight the importance of adequate and continued support, which can be in varying modalities and that this increased support is cost-effective in the long run.

Promoting increases in physical activity is central to prevention of obesity, weight loss among obese individuals, and in maintenance of weight loss. In a recent review, Goldberg and King (2007) report that to prevent age-related weight gain generally, levels of vigorous physical activity above the usually recommended 30 minutes daily (e.g., to 45 to 60 minutes daily) may be necessary. For weight loss, physical activity interventions alone usually produce only modest results (e.g., 3 to 6 pounds), suggesting that for obese individuals significant weight loss also requires dietary change. Goldberg and King (2007) also note that current research suggests that high levels of physical activity (e.g., 40 to 90 minutes daily) may be necessary for weight loss maintenance.

Meta-analysis of psychobehavioral interventions in preventing weight gains or reducing weight among U.S. multiethnic and minority adults has indicated that multicomponent (versus single component) lifestyle interventions were efficacious and suggested that incorporation of individual sessions, family involvement, and problem-solving strategies are useful (Seo & Sa, 2008). Beyond traditional individually delivered weight loss intervention, recent research has also focused on environmental approaches to healthy eating (Story, Kapingst, Robinson-O'Brien, & Glanz, 2008) and worksite weight-loss intervention (Anderson et al., 2009). Given the dramatic recent increases in childhood obesity and the robust association of childhood and adolescent obesity with obesity in adulthood, it is clear that intervention efforts targeting weight loss in children are essential. Approaches with at least preliminary evidence of success in producing meaningful and sustained weight loss include school-based interventions (Katz, 2009), family-based approaches (Epstein, Paluch, Roemmich, & Beecher, 2007), and environmental and policy approaches (Brennan, Castro, Brownson, Claus, & Orleans, 2011).

Physical activity level and sedentary behavior are risk factors for the development of many chronic illnesses and negative health conditions including obesity, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and coronary heart disease. Interestingly, recent research suggests that sedentary behavior may be a distinct risk factor, independent of commonly used measures of physical activity, for a variety of adverse health outcomes in adults (Thorpe, Owen, Neuhaus, & Dunstan, 2011). The “dose” of physical activity that is needed continues to be debated; however, recent research has emphasized that even light activity improves health in sedentary individuals and that recommending small, gradual increases in activity helps to mitigate the incidence of adverse events and improve adherence to physical activity regimens (Powell, Paluch, & Blair, 2011). Given the role of physical activity and sedentary behavior in development of chronic illness, interventions focused on increasing activity levels and exercise behavior continue to be central to clinical health psychology and behavioral medicine. For example, current evidence supports the effectiveness of increasing physical activity in the prevention and treatment of obesity (Goldberg & King, 2007) and in the management of type 2 diabetes (Umpierre et al., 2011). Exercise has sustained beneficial effects on depression (Conn, 2010; Hoffman et al., 2011), and a recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials concluded that exercise is effective in reducing depressive symptoms in individuals with chronic illness, particularly those with mild-to-moderate depression (Herring, Puetz, O'Connor, & Dishman, 2012). Exercise has also been found to improve various aspects of cognitive functioning, including attention, processing speed, executive functioning, and memory (Smith, Blumenthal et al., 2010).

Given the evidence that declining physical activity and increases in sedentary behavior in the population over recent decades derive largely from environmental factors (Brownson, Boehmer, & Luke, 2005) interventions have increasingly moved beyond individually delivered approaches. Examples include worksite interventions (Abraham & Graham-Rower, 2009) and ecological approaches (e.g., increasing the “walk-ability” of communities and access to recreation sites) to increase physical activity (Sallis et al., 2006). Further, given the dramatic increase in childhood obesity and the success of adult-focused diabetes prevention efforts focused on increasing physical activity (Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group, 2002), school-based exercise programs have been the focus of recent RCTs demonstrating improvement in body composition, fitness, and insulin sensitivity in children (Carrel et al., 2005). However, maintenance of such benefits over prolonged school vacations can be problematic (Carrel et al., 2007).

HIV continues to be a major public health burden, with incidence rates in the United States ranging from 47,800 to 56,000 over the years 2006 to 2009 (Prejean et al., 2011), making preventive intervention a continued focus of clinical health psychology and behavioral medicine. HIV prevention efforts have involved a combination of behavioral (e.g., condom use, reduction in presex alcohol and drug use, reduction in needle-sharing among drug users), biomedical (e.g., antiretroviral medications to reduce transmission), and structural (i.e., social, economic, political) intervention strategies; many of these interventions have been found effective in reducing HIV risk behaviors by 25% to 50% (see Rotheram-Borus, Swendeman, & Chovnick, 2009). Although a variety of interventions have proven useful and cost-effective, inadequate funding, imperfect targeting strategies, and a problematic policy environment have been barriers to the widespread implementation of these life-saving interventions (Holtgrave & Curran, 2006).

Given these issues, HIV prevention efforts have increasingly focused on targeted interventions for high-risk groups. Groups at particular risk include young men who have sex with men, the only group that continues to show an increase in HIV infection, and African American men and women who have an estimated HIV incidence rate 7 times that of whites (Prejean et al., 2011). In a recent review of prevention efforts in young men who have sex with men, Mustanski, Newcomb, Du Bois, Garcia, and Grov (2011) suggest that Internet-based interventions, integration of biomedical and behavioral approaches, and interventions that take advantage of community and network factors are particularly promising. African American women also represent a high-risk target group. A recent meta-analysis indicated that interventions that used gender- or culture-specific materials, used female deliverers, addressed empowerment issues, provided skills training in condom use and negotiation of safer sex, and used role-playing to teach negotiation skills were particularly efficacious in HIV prevention in this risk group (Crepaz et al., 2009). Individuals who already have a sexually transmitted disease are at higher risk for additional STDs as well as HIV infection; a recent meta-analysis confirmed that targeting prevention efforts toward patients at STD clinics is effective and should be a high public health priority (Scott-Sheldon, Fielder, & Carey, 2010).

Many individuals are characterized by more than one unhealthy behavior; smokers often are relatively sedentary, as are many individuals who consume a diet too high in calories, refined sugars, and saturated fat. The scope of this problem is even greater, if emotional difficulties such as depression are included in the definition of multiple risks. This creates the need for effective approaches to multiple risk behavior change interventions (J. J. Prochaska, Nigg, Spring, Velicer, & Prochaska, 2010; J. J. Prochaska & Prochaska, 2009). As seen in the preceding discussion of interventions for obesity and weight loss, the targeting of multiple behaviors (e.g., diet and exercise) is standard in many instances. Yet, RCTs of multiple health behavior change approaches are a relatively new development in the field. In many cases, the issue poses minimal difficulties. For example, treatment of other behavioral risks (e.g., diet, sun exposure) does not appear to interfere with the effectiveness of smoking cessation (J. J. Prochaska, Velicer, Prochaska, Delucchi, & Hall, 2006). Other combinations of risks poses more complicated challenges. For example, many smokers express the concern that smoking cessation will lead to weight gain, and weight gain can lead to failure to achieve and maintain abstinence. Combined treatments for smoking cessation and weight management can increase abstinence and reduce weight gain initially, but these benefits are often not maintained (Spring et al., 2009), indicating the need for additional treatment methods.

In weight loss efforts, comorbid depression is a common concern (Fabricatore & Wadden, 2006). Obesity and depression have a robust concurrent association, perhaps reflecting a bidirectional pattern of influence over time (Atlantis & Baker, 2008; Markowitz, Friedman, & Arent, 2008). The prospective association in which depression predicts weight gain over time is somewhat stronger than the role of initial adiposity in later depression (Atlantis & Baker, 2008; Gariepy, Wang, Lesage, & Schmitz, 2010; Patten, Williams, Lavorato, Khaled, & Bulloch, 2011). Attrition from clinical weight loss trials has been found to be related to depression at baseline and poor early weight loss (Fabricatore et al., 2009). In an RCT aimed at addressing co-occurring depression, women with comorbid obesity and depression were randomized to behavioral weight loss or behavioral weight loss combined with cognitive-behavioral depression management. Women in both groups demonstrated significant weight loss and reduction in levels of depression (Linde et al., 2011). The failure to find added benefit of specific depression treatment may reflect common elements across these two interventions. Both included behavioral activation, problem-solving training, social support, and cognitive restructuring. Hence, the weight loss only condition may have included useful treatment elements for addressing depression. High levels of stress have a modest but significant prospective association with increasing adiposity (Wardle, Chida, Gibson, Whitaker, & Steptoe, 2011). Hence, the effects of stress reduction as an adjunctive treatment in weight loss programs among patients experiencing high levels of stress or related emotion regulation difficulties is a potentially important topic for future intervention research. Given the prevalence of both depression and obesity in the general population, the efficacy and effectiveness of approaches to weight loss among depressed persons is an important topic for further research.

The co-occurrence of smoking and depression is also common and poses similar challenges (Aubin, Rollema, Svensson, & Winterer, 2012; Hall & Prochaska, 2009). Traditional cessation programs can be successfully adapted for use with depressed smokers (Hall et al., 2006), and smoking cessation does not appear to increase depression or other emotional symptoms (Bolan, West, & Gunnell, 2011), even among initially depressed smokers (J. J. Prochaska, Hall, Tsoh, et al., 2008). However, rates of successful cessation and maintained abstinence are often lower in depressed smokers (Hall & Prochaska, 2009). Preliminary evidence suggests that the addition of CBT for depression may be a useful addition to cessation treatments for individuals prone to depression (Kapson & Haaga, 2010). Further, physical activity may facilitate abstinence after smoking cessation (J. J. Prochaska, Hall, Humfleet, et al., 2008), especially in light of the fact that exercise can have beneficial effects on depression (Blumenthal, 2011).

Chronic medical illness poses a multifaceted adaptive challenge for patients and their families. The physical symptoms and distress (i.e., pain) stemming from these illnesses can be burdensome, and they often are the cause of serious reductions in functional activity across a variety of roles and domains (Stanton, Revenson, & Tennen, 2007). Depression and other emotional difficulties are much more common among persons with chronic medical illness, given these stressors (Smith, 2010a). Patients must also adhere to often complex medical regimens, and the extent to which they do so has important effects on health outcomes (Cramer, Benedict, Muszbek, Keskinaslan, & Khan, 2008; Gehi, Ali, Na, & Whooley, 2007). Yet, even in conditions like cardiovascular disease where the value of medications is quite substantial, as little as 50% of prescribed medications are taken (Baroletti & Dell'Orfano, 2010). In the same health care settings in which psychologists provide services to individuals with chronic medical illness, they are increasingly called to manage other presenting complaints and problems where traditional medical approaches are not optimal (e.g., sleep disturbance, somatoform disorders). In what follows here, we review intervention research findings on both the most common medical illnesses, and complaints that often are presented in medical settings.

Approaches to adjunctive psychosocial care vary somewhat across specific illness and presenting problems, but several are broadly applicable. Cognitive-behavioral interventions for stress, pain, sleep, somatic complaints, and emotional adjustment are widely used, as are supportive-expressive therapies. Rehabilitation often includes operant and exposure-based treatments for progressively increasing functional activities and reducing avoidance of feared activities. Couple and family approaches are less commonly used, but have considerable potential given that the patient's degree of adaption to chronic illness affects and is affected by family members. Exercise interventions have broad applicability. They can improve functional activity, but in some conditions are useful in treating the underlying disease and in improving emotional adjustment (Herring et al., 2012).

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the United States, as it is in many industrialized nations. One of these conditions, essential hypertension is a contributing cause of the other two primary cardiovascular diseases—coronary heart disease and stroke—but also increases risk of other serious illness (e.g., renal disease).

Behavior changes involving diet, exercise, and weight loss are standard aspects of the medical management of essential hypertension, both as an initial intervention for mild levels and as an adjunct to pharmacologic treatment. This is particularly true in the case of overweight individuals, as adiposity is a common contributing factor in essential hypertension. Clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy and effectiveness of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) and DASH-low sodium diets in preventing and treating hypertension (Appel et al., 2006). Compared to a typical U.S. diet, the DASH diet is low in saturated fat, red meat, and refined sugars, and high in intake of fruits, vegetables, and low fat dairy products, with a substantial portion of the diet including whole grain, fish, poultry, and nuts. Adherence to DASH diet has been found to reduce blood pressure by a clinically meaningful 5 to 10 mmHg among high-risk individuals, and risk of CHD and stroke by as much as 20% (Fung et al., 2008).

These important reductions in blood pressure can be augmented when the DASH diet is accompanied by exercise and weight loss interventions. For example, combining the DASH diet with an exercise program and a reduction in caloric intake intended to produce weight loss improves both standard clinic-based measurements of blood pressure and levels of the more prognostic indicator of ambulatory blood pressure for overweight hypertensives (Blumenthal, Babyak, Hinderliter, et al., 2010). This combined intervention was also more effective in altering other markers of vascular, cardiac, and metabolic risk including pulse wave velocity (i.e., arterial stiffness), left ventricular mass, insulin insensitivity or glucose regulation, and plasma cholesterol and triglycerides (Blumenthal, Babyak, Sherwood, et al., 2010; Blumenthal, Babyak, Hinderliter, et al., 2010). Hence, the combined dietary, exercise, and weight loss intervention has broad health benefits, especially among overweight persons. The exercise and weight loss also reduce depressive symptoms among hypertensives, especially among those with higher initial levels of depression (Smith, Blumenthal, Babyak, et al., 2007). Attenuated nocturnal decreases (i.e., “dipping”) in blood pressure are an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, more common among African Americans than whites. In this regard, it is important to note preliminary evidence that the DASH diet can improve nocturnal blood pressure dipping among African Americans (Prather, Blumenthal, Hinderliter, & Sherwood, 2011).

Chronic stress is associated with increased risk of high blood pressure and the development of diagnosed hypertension (Sparrenberger et al., 2009), providing the rationale for various stress management and relaxation therapies as adjuncts to traditional approaches to the management of hypertension. A meta-analysis of 25 trials including a total of more than 1,000 patients found small but significant reductions (SBP −5.5 mmHg; DBP −3.5 mmHg) in blood pressure (Dickinson et al., 2008). Although even small blood pressure reductions can be clinically meaningful, methodological weaknesses of some the individual trials (e.g., small sample sizes, failure to control nonspecific factors) raise concerns about the reproducibility of this result. As a result, exercise, dietary, and weight loss interventions have stronger support as treatments for hypertension, compared to stress management.

The standard medical management of coronary heart disease (CHD) has included behavioral interventions for many years. Adherence to diet, exercise, and smoking cessation recommendations for CHD patients is associated with a 40% to 50% reduction in recurrent cardiac events (e.g., additional myocardial infarction, death) within the first 6 months after hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome (Chow et al., 2010). Among smokers who develop acute coronary disease, between 30% and 50% quit without formal smoking cessation intervention. However, interventions for smoking cessation produce added benefits among these patients, increasing the chances of successful cessation by 60% (Barth, Critchley, & Bengel, 2008) with associated reductions in risk of future cardiac events following successful cessation. However, quit rates are far from satisfactory, suggesting the need for more effective interventions and more consistent implementation of effective approaches. Meta-analyses have consistently demonstrated that exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation reduces recurrent cardiac events and all-cause mortality by approximately 20% (Taylor et al., 2004), although improvements in access, implementation, and adherence are needed.

The effects of psychological stress and negative emotion on the development and course of coronary heart disease (CHD) are well-established, with extensive evidence accumulating from animal models, human epidemiological research, and clinical studies of CHD patient populations (Williams, 2008). Specific forms of stress linked to CHD include work stress (Eller et al., 2009) and stress in personal close relationships (De Vogli et al., 2007; Matthews & Gump, 2002; Orth-Gomer et al., 2000; Rohrbaugh et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2012). Further, psychological stress and negative emotion are associated with increased CHD risk across the full time course of the disease, from the development and progression of asymptomatic atherosclerosis, to the emergence of cardiac events, and the course of established CHD (Bhattacharyya & Steptoe, 2007; Williams, 2008). Given the important historical role played by the Type A behavior pattern in this research area, a major aspect of this evidence concerns the association of anger and hostility—key unhealthy elements of the broader Type A pattern—with the development and course of CHD (Chida & Steptoe, 2009). However, in recent years extensive evidence has accumulated indicating that depression and anxiety are also risk factors for the development of CHD among initially healthy persons, and for increased risk among patients with disease (Nicholson, Kuper, & Hemingway, 2006; Rutledge, Reiss, Linke, Greenberg, & Mills, 2006; Smith, 2010a; Suls & Bunde, 2005). These associations with CHD provide the foundation for a variety of studies of the effectiveness of stress management and interventions for negative affective symptoms and conditions.

The potential value of such approaches was initially demonstrated in the Recurrent Coronary Prevention Project (RCPP), in which group therapy intended to reduce Type A behavior among CHD patients not only successfully modified this behavioral endpoint, but also resulted in a significant and nearly 50% reduction in subsequent coronary events (15% in comparison condition versus 8% in treatment condition; Friedman et al., 1986). A recent meta-analysis of RCTs of stress management and similar psychosocial interventions for patients with CHD found evidence of a significant reduction of more than 40% in recurrent coronary events for 2 years after treatment and a 27% reduction in all-cause mortality over the same follow-up period (Linden, Phillips, & Leclerc, 2007). These benefits were limited to men, however, with no effect on prognosis among women. Further, interventions were significantly more effective when initiated 2 months or more after the initial coronary event rather than closer in time to hospitalization, and the interventions were significantly more effective if they also reduced indications of emotional distress (Linden et al., 2007).

Subsequent studies have confirmed the general effectiveness of these interventions. In a randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral stress management in a sample of more than 350 CHD patients, the intervention produced a significant reduction in risk of recurrent cardiovascular events. Specifically, 47% of patients receiving usual care experienced a recurrent cardiovascular event over an average of 8 years of follow-up, compared to 36% of the patients receiving CBT (Gulliksson et al., 2011). Importantly, a recent RCT of cognitive-behavioral stress management for women with CHD (Orth-Gomer et al., 2009) found that over a 7-year follow-up women in the treatment group had a 3-times smaller risk of death than those in the control (i.e., 7% mortality versus 20%). Thus, the CBT approach was successfully adapted for women with CHD in this case. Given the considerable attention to the study of anger and CHD (Chida & Steptoe, 2009) and the availability of empirically supported anger treatments (Smith & Traupman, 2012), it is surprising that few studies have directly examined the benefits of such interventions among CHD patients. One small RCT did find that CBT for anger and hostility produced a significant reduction in recurrent coronary events and a related savings in health care costs (Davidson, Gidron, Mostofsky, & Trudeau, 2007). Stress management interventions have also been found to alter biomarkers of CHD severity (e.g., reductions in stress-induced cardiac ischemia, increases in flow-mediated arterial dilation), illustrating plausible mechanisms underlying the effect of psychosocial interventions on coronary outcomes (Blumenthal, Sherwood et al., 2005). However, it is important to note that other systematic reviews of the topic (Whalley et al., 2011) have not reached the same positive conclusions as those of Linden et al. (2007).

In another historically important behavioral approach to the treatment of coronary disease, Ornish and colleagues (1990, 1998) have examined the effects among CHD patients of a comprehensive lifestyle change program involving a low-fat, whole foods diet (i.e., whole grains, fruits, vegetables), moderate exercise, stress management, and attendance at regular support group meetings. Early RCTs of the program demonstrated significant effects on the coronary risk factors, extent of coronary artery disease, other indicators of underlying disease severity, and coronary events (e.g., Gould et al., 1995; Ornish et al., 1990, 1998). Subsequent research has demonstrated additional beneficial effects on coronary outcomes, various aspects of quality of life, and related health care costs (for reviews, see Vizza, 2012; Weidner & Kendel, 2010).

The extensive evidence of an association between depression and the course of CHD has prompted efforts to examine the benefits of related treatments. The most notable effort was the multicenter Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) (Berkman et al., 2003). ENRICHD enrolled more than 2,000 CHD patients selected primarily for elevated levels of depression, but also for social isolation, a related and significant psychosocial risk for poor cardiac outcomes. In comparison to the control condition, the CBT-based intervention produced small but significant improvements in depression and social isolation, but no effects on the primary combined outcomes of death and recurrent coronary events (Berkman et al., 2003). Secondary subgroup analyses indicated that there were beneficial effects on the primary outcome for white men (Schneiderman et al., 2004) and those patients who had received at least some of the CBT intervention in group as opposed to only individual sessions (Saab et al., 2009).

CBT for depression has been found to be effective for CHD patients experiencing depression following coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) (Freedland et al., 2009). Also among depressed post-CABG patients, telephone-based collaborative care that includes psychoeducation and supportive counseling for depression was found to be effective in reducing negative mood symptoms, improving HQOL, and levels of physical functioning (Rollman et al., 2009). Davidson et al. (2010) randomized depressed acute coronary syndrome patients to usual care or an enhanced depression care condition in which patients self-selected into either pharmacotherapy or problem-solving therapy, followed by stepped care for continuing depression. The treatment group showed significantly better depression outcomes and a significant reduction in adverse cardiac events, although the latter outcome should be considered preliminary given the small number of events. To date, studies evaluating the effects of pharmacotherapy for depression in CHD patients have found mixed evidence of effects on depression, and no evidence of improved cardiac outcomes (for a review, see Kop & Plumoff, 2012).

As noted above, exercise is effective for CHD improving prognosis for patients, and it has also been found to improve depression. Hence, exercise seems promising as a potential treatment for depressed CHD patients (Blumenthal, 2011; Smith 2006b). However, it is important to note that the supporting evidence is indirect and preliminary, and such exercise interventions for depression in CHD patients would need to address the fact that depression predicts failure to complete exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (Casey, Hughes, Waechter, Josephson, & Rosneck, 2008).

Given the high prevalence of depression in various CHD patient groups and its association with adverse events and mortality in this population, the American Heart Association has endorsed screening and increased availability of depression management for CHD patients (Lichtman et al., 2008). However, to date there are no empirical demonstrations that such procedures result in improved care or cardiac outcomes (Thombs et al., 2008). Nonetheless, depression is a direct contributor to poor HQOL, and can interfere with other behavioral interventions with well-established benefits for CHD patients, such as exercise (Casey et al., 2008) and smoking cessation (Thorndike et al., 2008). Hence, depression treatment should be a regular focus in the clinical management of CHD, but one whose effect is not as strong as would be hoped.