Chapter 4

Practice-Oriented Research

Approaches and Applications

Louis Castonguay, Michael Barkham, Wolfgang Lutz, and Andrew McAleavey

The authors are most grateful for the tremendous help provided by Soo Jeong Youn in preparing this chapter.

There are many controversies in the field of psychotherapy. Numerous debates remain ongoing, for example, about what treatments are (or are not) effective for certain disorders and what variables are responsible for change. Although these debates are of great conceptual and clinical significance, they fade in comparison to the gravity of the schism that is at the core of clinical and counseling psychology. While these disciplines, as well as many training programs in other mental health professions, are based on the scientist-practitioner model, it is well documented that psychotherapists are not frequently and substantially influenced by empirical findings when they conduct their case formulations, treatment plan, and implementations (e.g., Cohen, Sargent, & Sechrest, 1986; Morrow-Bradley & Elliott, 1986).

There are a number of ways to explain the apparent indifference of clinicians toward psychotherapy research. To begin with, many scientific investigations are perceived as being limited in terms of their clinical relevance. The emphasis on internal validity, especially in traditional randomized controlled trials (RCTs), has sometimes come at a cost in terms of external validity. For instance, the focus on setting, a priori, the number of sessions and inclusion/exclusion criteria, among other constraints required for controlled research, may well reduce error variance. However, the generalization of the findings to everyday practice is not always clear-cut (for further elaboration see Chapters 1, 3, and 14, this volume). It has also been argued that researchers pay limited attention to the concerns that therapists have when working with their clients (Beutler, Williams, Wakefield, & Entwistle, 1995). As described elsewhere (Castonguay, Boswell, et al., 2010), this could be viewed as a consequence or a reflection of “empirical imperialism” that has prevailed in many programs of research in which individuals who see very few clients per week decide what should be studied and how it should be investigated, to understand and facilitate the process of change.

The argument has also been made that clinicians would pay more attention to research findings if they were involved in research (e.g., Elliott & Morrow-Bradley, 1994). However, a number of obstacles can interfere with such involvement. Many therapists conducted research projects during graduate training that were unrelated to their clinical work. Similarly, not every clinician had the opportunity to work with an advisor who was conducting research while also treating psychotherapy clients of their own. Consequently, many clinicians lacked an early-career model based on conducting scientifically rigorous and clinically relevant studies that would then help them identify questions that could make a difference in their clinical work, or to help identify the most appropriate methods to investigate these questions. Full-time clinicians, even those who were mentored by ideal scholars, are also confronted with pragmatic obstacles that can seriously interfere with an involvement in research, such as limited time, lack of resources, and difficulties in keeping up-to-date with methodological and statistical advances.

Needless to say, many have lamented over the gap between science and practice, and, over the six decades since the inception of the scientific-practitioner model (Raimy, 1950), several efforts have been made to foster and/or repair this concept (e.g., Soldz & McCullogh, 2000; Talley, Strupp, & Butler, 1994). The various avenues that are currently being promoted (and debated) to define evidence-based practice reflect a resurgence of the need to build stronger links between research and practice (e.g., Goodheart, Kazdin, & Sternberg, 2006; Norcross, Beutler, & Levant, 2006). Interestingly, it could also be argued that the current attention given to evidence-based practice has been triggered by the delineation and advocacy of empirically supported treatments (ESTs; Chambless & Ollendick, 2001). Although several scholars have warned that the promulgation of ESTs could deepen the schism between research and clinicians (e.g., Elliott, 1998), there seems to be no doubt that the EST movement has galvanized diverse efforts to foster the use of empirical information in the conduct of clinical tasks.

Directly related to the EST movement are the empirical investigations that have been conducted to test whether treatments shown to be effective under the stringent criteria of controlled trials also work when delivered in naturalistic settings. These effectiveness, as opposed to efficacy, studies are guided by the rationale that scientific advances will improve mental health care if it can be demonstrated that effective treatments (i.e., yielding large effect sizes) for specific and debilitating problems can be implemented and adopted in routine clinical care (Tai et al., 2010). A related effort has been the publication of important books and articles aimed at disseminating the research findings on ESTs, with the goal of offering a list of “treatments that work” (e.g., Nathan & Gorman, 2002). Complementing such publications are a large number of books describing how clinicians can apply specific ESTs. In fact, a number of these well known books are published versions of treatment manuals that have been used in clinical trials (e.g., Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979; Klerman, Weissman, Rounsaville, & Chevron, 1984). As argued elsewhere (Castonguay, Schut, Constantino, & Halperin, 1999), such treatment manuals provide specific guidelines for interventions that can be extremely helpful to clinicians, as long as they are not imposed as the only form of therapy to be reimbursed. Nor that they are prescribed or used rigidly without being individualized to the needs of particular clients, and without consideration of other empirical data that can help foster process and outcome.

In response to the effort to bring science into practice via the validation and dissemination of specific treatments for particular disorders, came other initiatives emphasizing different variables and methodologies. These included the task forces on empirically supported therapeutic relationships (Norcross, 2011) and empirically based principles of change (Castonguay & Beutler, 2005a). The books that emerged from these task forces not only review the literature about variables related to the client and relationship, but also offer clinical guidelines derived from the empirical literature. In addition, noteworthy contributions (e.g., texts by Cooper [2008] and Lebow [2006]), have successfully taken on the challenge of presenting, without jargon, how research findings can be used in clinical practice.

Even though the efforts reported above focus on different variables and rely on different avenues of dissemination, they all share a top-down approach: that is, science is transmitted, and potentially adopted, via researchers informing therapists about the issues that have been studied and the lessons that can be derived from the findings. For example, in the United Kingdom some of these findings, derived from traditional RCTs and related meta-analytic studies, largely determine the national treatment guidelines to which practitioners and services are required to adhere. In this chapter, we refer to these efforts as manifestations of the paradigm of evidence-based practice. Although such efforts have and will continue to provide useful information to therapists, they nevertheless all reflect a more or less benign form of empirical imperialism.

One possible way to avoid or reduce empirical imperialism is for clinicians to be actively engaged in the design and/or implementation of research protocols. Such practice-orientated research, conducted not only for but also, at least in some way, by clinicians, reflects a bottom-up approach to building and using scientific knowledge. This approach is likely to create new pathways of connections between science and practice, both in terms of process and outcome. By fostering a sense of shared ownership and mutual collaboration between researchers and clinicians (e.g., in deciding what data to collect and/or how to collect it), this actionable approach can build on complementary expertise, compensate for limitations of knowledge and experience, and thus foster new ways of conducting and investigating psychotherapy. By emerging directly from the context in which therapists are working, practice-oriented research is likely to be intrinsically relevant to their concerns and can optimally “confound” research and practice: that is, when the design of studies leads clinicians to perform activities that are simultaneously and intrinsically serving both clinical and scientific purposes.

The primary goal of this chapter is to describe three main approaches within the overarching paradigm of practice-oriented research: patient-focused research, practice-based evidence, and practice research networks. All three approaches share commonalities, the most notable being the collection of data within naturalistic settings. However, they also represent, in the order that they are presented in this chapter, a gradual variation on two crucial dimensions: first, in terms of the focus of research knowledge (from very specific to very broad), and second, in terms of active involvement of practitioners in the design, implementation, and dissemination of research. Although this chapter does not stand as a comprehensive review, it provides examples of psychotherapy studies that have been conducted within each of the three approaches highlighted and their application to practice. The chapter also briefly addresses some additional lines of inquiry that are aimed at fostering the link between research and practice.

We hasten to say that we do not view the strategies of accumulation and dissemination of empirical knowledge described in this chapter (i.e., practice-oriented research) as being superior to those typically associated with the evidence-based practice movement. Rather, we would argue for adopting a position of equipoise between these two complementary paradigms. Although traditional RCTs are often viewed as the gold standard within a hierarchy of evidence, this position has been challenged: “The notion that evidence can be reliably placed in hierarchies is illusory. Hierarchies place RCTs on an undeserved pedestal, for…although the technique has advantages it also has significant disadvantages” (Rawlins, 2008).1 And in relation to the potential of practice-based evidence, Kazdin (2008) has written that “[W]e are letting the knowledge from practice drip through the holes of a colander.” The colander effect is a salutary reminder of the richness of data that is potentially collectable but invariably lost every day from routine practice. A position of equipoise would advocate that neither paradigm alone—evidence-based practice or practice-oriented research—is able to yield a robust knowledge base for the psychological therapies. Furthermore, it is important to recognize that the methods typically associated with these approaches are not mutually exclusive. As we describe later, for example, RCTs have been designed and implemented within the context of practice research networks. Hence, rather than viewing these two approaches as dichotomous, a robust knowledge-base needs to be considered as a chiasmus that delivers evidence-based practice and practice-oriented evidence (Barkham & Margison, 2007).

Patient-Focused Research

This section on patient-focused research has the goal of presenting one way of thinking about the scientist-practitioner gap from a scientist's as well as a practitioner's perspective. The main tool to achieve this goal is the careful study of patterns of patient change as well as tracking individual patients' progress over the course of treatment and feeding back the actual treatment progress into clinical practice. Patient-focused research provides tools in order to support, but not replace, clinical decision-making with actual ongoing research data and specially developed decision support tools. The goal is, for example, to identify negative and positive developments early on in treatment and then to feed these back to therapists so they can combine science and practice immediately during the ongoing treatment. This is akin to physicians using lab test data and vital sign measures to manage physical ailments such as diabetes (see Lambert, 2010).

Importantly, the models discussed in this section are based on a generic approach to psychotherapy. Psychotherapies are viewed as a class of treatments defined by overlapping techniques, mechanisms, and proposed outcomes. Outcomes are measured by summing items related to many disorders. Instead of identifying particular treatments for particular diagnoses as is the case in clinical trials, patient-focused research focuses more on the (real time) improvement of the actual treatment as implemented and the development of tools in order to achieve that task (Lutz, 2002). Overall, it supports a research perspective more focused on outcomes and the improvement of actual clinical practice based on empirical knowledge and less based on a debate about therapeutic schools (e.g., Goldfried, 1984; Grawe, 1997). Accordingly, the core of this approach requires research to be conducted on the course of patient change for individual clients/patients to learn about differences in patient change as well as subgroups of patients with specific patterns of change.

To date, the field of psychotherapy research has studied different types of psychopathology and accumulated a large amount of knowledge in terms of specific treatments for particular diagnostic subgroups (e.g., Barlow, 2007; Nathan & Gorman, 2002; Schulte, 1998). However, considerably less is known about different types of patient change. This situation is puzzling given that research has provided support for patient variability as a substantial source in explaining outcome variance, which Norcross and Lambert (2012) have estimated to be in the region of 30%. In contrast, treatment techniques have been reported as explaining only a small portion of the outcome variance (e.g., Lambert & Ogles, 2004; Wampold, 2001). Accordingly, careful examinations of how and when patients progress during treatment, or fail to do so, may both increase our understanding of psychotherapy and provide us with tools that could improve its effectiveness.

The following section is organized in three parts. First, a short introduction sets out the history of patient-focused research (dosage and phase models of therapeutic progress). Second, the main focus and themes of patient-focused research are described and discussed (rationally and empirically derived methods, nearest neighbors techniques, and new ways of detecting patterns of patient change and variability). And finally, the evidence-base for applying these methods to yield feedback to therapists is considered.

Dosage and Phase Models of Therapeutic Progress

The theoretical origins of patient-focused psychotherapy research, often described in the literature as the “expected treatment response model,” are the dosage and phase models of psychotherapy. The dosage model of psychotherapeutic effectiveness established a positive, but negatively accelerating, relationship between the number of sessions (dose) and the probability of patient improvement (effect) such that increased number of sessions is associated with diminishing returns (Howard, Kopta, Krause, & Orlinsky, 1986). In subsequent work, Howard, Lueger, Maling, and Martinovich (1993) as well as Kadera, Lambert, and Andrews (1996) interpreted findings as representing rapid improvement early in treatment while in later phases increasing numbers of sessions were needed to reach a higher percentage of changed patients (see also Chapter 6, this volume). For instance, Howard et al. (1986), analyzing data on 2,431 patients from 15 studies, found that after 2 sessions 30% of patients had shown positive results. The percentages increased to 41% after 4 sessions, 53% after 8 sessions, and 75% after 26 sessions. In an extended analysis, Lambert, Hansen, and Finch (2001), using survival statistics and a more refined clinically significant change criteria, showed that these rates of improvement were overestimates of the speed of improvement and were dependent on patients' pretreatment functioning. Their results showed that 50% of the patients who were in the dysfunctional range before treatment needed 21 sessions of treatment to reach the criteria for clinically significant change. However, for 70% of patients in the dysfunctional range to reach clinically significant change, more than 35 sessions were necessary. Further research has shown differential patient change rates by diagnosis and symptoms (Barkham et al., 1996; Kopta, Howard, Lowry, & Beutler, 1994; Maling, Gurtman, & Howard, 1995). In addition, Hansen, Lambert, and Forman (2002) reported that in clinical practice success rates are lower when treatment plans do not allow for enough sessions. Hence, a variety of factors will impact on the rate of change for each individual patient. An extension of this line of research can be seen in the good-enough level of change concept (e.g., Barkham et al., 2006; Stiles, Barkham, Connell, & Mellor-Clark, 2008; see later in this chapter).

The phase model further amplifies the dose-effect model by focusing on which specific dimensions of outcome are changing and in what temporal sequence (Howard et al., 1993). It proposes three sequential and progressive phases of the therapeutic recovery process and assumes sequential improvement in the following areas of patient change: (1) remoralization, the enhancement of well-being; (2) remediation, the achievement of symptomatic relief; and (3) rehabilitation, the reduction of maladaptive behaviors, cognitions, and interpersonal problems that interfere with current life functioning (e.g., self-management, work, family, and partner relationships). In applying the dose-effect and phase models to therapeutic change, the decelerating curve of improvement can be related to the increasing difficulty of achieving treatment goals over the course of psychotherapy. Moreover, a causal relationship between changes in these dimensions was proposed with the phase model. That is, improvement in well-being is assumed to be necessary, but not sufficient, for a reduction of symptoms, which is assumed to be necessary for the subsequent enhancement in life functioning (cf. Stulz & Lutz, 2007).

In a replication study, Stulz and Lutz (2007) identified three patient subgroups on the basis of their development over the course of treatment in the dimensions of the phase model. In all of these subgroups, well-being increased most rapidly, followed by symptom reduction, while improvement in life-functioning was slowest. This finding supports the notion of differential change sensitivity for the three dimensions. Further, approximately two thirds of cases were consistent with the predicted temporal sequencing of phases (i.e., well-being to symptoms to functioning). However, a smaller but significant proportion of patients, approximately 30%, violated at least one of the two predicted sequences (e.g., moving directly from well-being to functioning). In addition, results suggested that the phase model seemed to be less powerful in describing treatment progress among more severely disturbed patients. A similar finding was also reported by Joyce, Ogrodniczuk, Piper, and McCallum (2002). In light of the earlier findings, further refinement focusing on differential change sequences between individuals is important.

Patient-Focused Research and Expected Treatment Response

The dosage and phase models define the process of recovery in psychotherapy for an average patient. However, patterns of improvement for individuals can vary significantly from the general trend (Krause, Howard, & Lutz, 1998). Thus, to accommodate this individuality, a model could be helpful that estimates an expected course of recovery for individual patients based on their progress-relevant pretreatment characteristics. Indeed, this was the starting point for patient-focused psychotherapy research (Howard, Moras, Brill, Martinovich, & Lutz, 1996). Patient-focused research is concerned with the monitoring, prediction, and evaluation of individual treatment progress during the course of therapy by means of the repeated assessment of outcome variables, the evaluation of these outcome variables through decision rules, and the feedback of this information to therapists and patients (e.g., Lambert, Hansen, et al., 2001; Lutz, 2002). Such quality management efforts have been recognized not only as a promising method but as evidence-based practice that identifies patients at risk for treatment failure, supports adaptive treatment planning during the course of treatment, and, as a result, enhances the likelihood of positive treatment outcomes (Lambert, 2010; Shimokawa, Lambert, & Smart, 2010).

Patient-focused research asks how well a particular treatment works for the actual treated patient (i.e., whether the patient's condition is responding to the treatment he or she is currently engaged in). The evaluation of progress depends on the idiosyncratic presentation of the patient with respect to his or her expected treatment response. For example, minimal progress by Session 8 might be insufficient for many patients to consider their treatment as a success. However, for a highly symptomatic patient with comorbid levels of impairment (e.g., multiple symptoms as well as interpersonal problems) such moderate progress might be considered a success (Lutz, Stulz, & Köck, 2009). As a result, feedback systems to support clinical decision making in psychotherapy should include decision rules that are able to evaluate treatment progress based on the individual patient's status (Barkham, Hardy, & Mellor-Clark, 2010; Lambert, 2010; Lutz, 2002; see also Chapter 6, this volume).

Two distinct approaches to decision rules have been used to determine expected progress and to provide feedback (cf. Lambert, Whipple, et al., 2002; Lutz, Lambert, et al., 2006). One approach comprises rationally derived methods that are based on predefined judgments about progress using clinicians' ratings based on changes in mental health functioning over sessions of psychotherapy. The other approach comprises empirically derived methods that, in contrast, are based on statistically derived expected treatment response (ETR) curves based on large available data sets that are respecified for each individual client.

Rationally Derived Methods

Rationally derived methods of patient-focused research use psychometric information based on standardized measures (e.g., the Brief Symptom Inventory [BSI]; Derogatis, 1993) to make an a priori definition about a patient's status and change. This then serves as a benchmark for his or her expected change and the evaluation of progress. A classic example of the rationally derived method can be seen in the concept of reliable and clinically significant change (Jacobson & Truax, 1991). The first component in this concept focuses on the actual amount of change achieved by the patient, which has to be greater than expected by measurement error of the instrument alone. The measurement error of an instrument depends on its reliability, hence the term reliable change (which comprises both reliable improvement and reliable deterioration). The second component, clinically significant change (or, more precisely, clinically significant improvement), occurs if a client who before treatment was more likely to belong to a patient sample is, at the final assessment, more likely to belong to a nonpatient sample (e.g., a community sample). Consequently, a patient has achieved reliable and clinically significant improvement if his or her score on the primary outcome measure meets both these criteria, indicating that the extent of improvement exceeds measurement error and the endpoint score is more likely to be drawn from a nonclinical population.

The following example of a rationally derived method used within a large feedback study is somewhat more complex. In a large-scale study funded by a German health insurance company comprising 1,708 patients within three regions of Germany, a rationally derived decision rule based on an extension of clinically significant change criteria was used (e.g., Lutz, Böhnke, & Köck, 2011). Feedback to the therapists was based on a patient's presentation at intake and on his or her amount of change by a certain session. This information was implemented into a graphical report, which was then fed back to clinicians who had the option to discuss these results via progress charts with patients.

To give feedback on initial patient status and patient progress to therapists at every assessment, all patients completed three instruments: the BSI, the Inventory for Interpersonal Problems (IIP; Horowitz, Rosenberg, Baer, Ureño, & Villaseñor, 1988), and a disorder-specific instrument (e.g., a patient diagnosed with a depressive disorder would complete the Beck Depression Inventory; Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961). Patients were first classified into three categories by each instrument according to their initial impairment. For example, patients were categorized as initially “highly impaired” if their pretreatment score on that specific instrument was above the mean of an outpatient sample. Initially “moderately impaired” patients scored below the mean of that reference sample, but above the cutoff score of a nonpatient population for that instrument (e.g., Jacobson & Truax, 1991). Patients who scored below that cutoff score were categorized as “minimally impaired.”

The feedback and evaluation of progress were based on the following decision rules. For the “minimally impaired” patients, each positive change resulted in a positive evaluation. For “moderately impaired” patients, change was considered positive only if improvement reached at least the predefined amount of the reliable change index (RCI) for that instrument. Finally, treatment change of “highly impaired” patients was viewed as positive only if patients fulfilled the criteria of reliable and clinically significant change. A negative reliable change was rated as deterioration independent of initial scores. The ratings for each of the three instruments were then integrated into a global score by summing them. Furthermore, the therapist could also be informed of the stability of treatment progress by reporting on progress over several administrations of the measures (for further details, see Lutz, Böhnke, & Köck, 2011; Lutz, Stulz, et al., 2009). The outcome findings of this study are briefly summarized in the subsequent section on feedback.

Empirically Derived Methods

Empirically derived methods define the expected treatment course based on previously treated patients with similar intake characteristics. These patient-specific databases are then used to determine the expected change for future patients. Furthermore, confidence or prediction intervals can be assigned around the predicted courses of improvement. Hence it is possible to provide an estimate of how much a patient's actual progress diverges from the expected course of change together with the probabilities of a successful outcome.

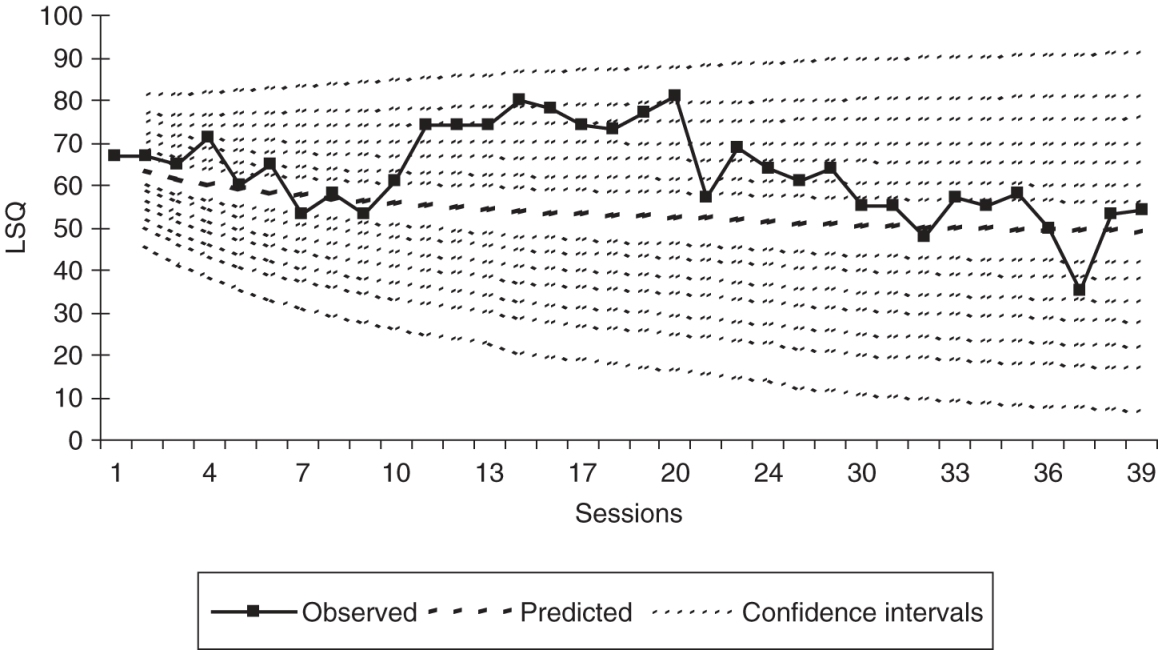

In an application of empirically derived ETRs, Lutz, Martinovich, and Howard (1999) analyzed data from 890 psychotherapy outpatients and identified a set of seven intake variables that allowed prediction of individual change (e.g., initial impairment, chronicity, previous treatment, patient's expectation of improvement). Figure 4.1 shows the ETR profile (predicted change based on intake variables) and the actual treatment progress of one selected patient with the Outcome Questionnaire-30 (OQ-30) as a dependent variable from an extended study with 4,365 patients (Lutz, Lambert, et al., 2006). To further explore the empirical decision system, different prediction intervals from 67% to 99.5% were considered around the predicted course of each patient. Using this schema, it was shown that the greater the number of actual scores a patient receives outside a confidence interval and the higher the interval, then the higher is the predictive validity of the actual score for the end of treatment.

In this way, actual treatment progress can be compared to the expected course of treatment and warning signals can be developed if a patient's progress falls below a predefined failure boundary. As the number of observed values falling below this failure boundary increases, for example between Sessions 2 and 8, then the probability of treatment failure increases. Also vice versa, as the number of observed values occurring above this failure boundary increases, then the probability of treatment success increases. Thus, the more and the further any extreme positive deviations are detected, then the higher is the probability for treatment success. Similarly, the more and the further any extreme negative deviations occur (e.g., early in treatment), then the higher the probability is for treatment failure (Lutz, Lambert, et al., 2006). These resulting percentages over the course of treatment can be employed as supporting tools by practitioners to adapt and potentially reevaluate their treatment strategy to enhance the patient's actual outcome. For example, a deviation from the ETR profile in a specific session might result in a “warning” feedback signal to the therapists and supervisors or other clinicians involved in the case (e.g., Finch, Lambert, & Schaalje, 2001; Lambert, Whipple, et al., 2002; Lueger et al., 2001; Lutz, 2002). Different approaches to ETR models have been developed that provide information to understand individual patient progress and to assist in improving treatment strategies. For example, the application of ETR models has been extended to different diagnostic groups or symptom patterns as well as being applied to the study of therapist effects. The models have also been improved by adding patient change information during the early course of treatment as predictors in order to have an adapted ETR model that is better able to predict patient change later in treatment (e.g., Lutz, Martinovich, Howard, & Leon, 2002; Lutz, Stulz, Smart, & Lambert, 2007). Two further extensions are presented here: One concerns how to identify subgroups of patients for developing ETRs, and the second concerns adjusting ETRs to different shapes or patterns of patient change.

Nearest Neighbors Techniques to Generate ETR Curves

To refine the prediction of ETR curves, Lutz et al. (2005) introduced an extended growth curve methodology that employs nearest neighbors (NN) techniques. This approach is based on research in areas other than psychotherapy in which large databases with many kinds of potentially relevant parameters (e.g., temperature and barometric pressure) recorded on a daily basis are used to make predictions of alpine avalanches (e.g., Brabec & Meister, 2001). This methodology was adapted by Lutz et al. (2005) in a sample of 203 psychotherapy outpatients seen in the United Kingdom to predict the individual course of psychotherapy based on the most similar previously treated patients (nearest neighbors). Similarity among patients was defined in terms of Euclidean distances between these variables. In a subsequent study, Lutz, Saunders, et al. (2006) tested the predictive validity and clinical utility of the approach in generating predictions for different treatment protocols (cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT] versus an integrative CBT and interpersonal treatment [IPT] protocol). The NN method created clinically meaningful patient-specific predictions between the treatment protocols for 27% of the patients, even though no average significant difference between the two protocols was found. Using a sample of 4,365 outpatients in the United States, Lutz, Lambert, et al. (2006) further demonstrated the NN technique to be superior to a rationally derived decision rule with respect to the prediction of the probability of treatment success, failure, and treatment duration using the Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45; e.g., Lambert, 2007).

In summary, these findings suggest that models of identifying similar patients could be an alternative approach to predicting individual treatment progress and to identifying patients at risk for treatment failure. It might be used in clinical settings either to evaluate the progress of an individual patient in a given treatment protocol, or to determine what treatment protocol (e.g., CBT or IPT) or treatment setting (e.g., individual, family, or group) is most likely to result in a positive outcome based on similar already treated patients. Furthermore, if used in the context of a clinical team, the model could be used to identify therapists who are most effective in working with a particular group of already treated patients (nearest neighbors) who could then provide consultation on treatment plans or supervision for a trainee or novice therapist working with the new case.

New Ways of Detecting Patterns of Patient Change and Variability

The models discussed previously take into account differences in patient change but they are built on the assumption that there is one specific shape of change (e.g., log-linear) for all patients in the data set. Although this assumption makes sense in order to estimate a general trend over time, actual patient change may follow highly variable temporal courses and this variation might not just be due to measurement error, but rather be clinically meaningful (e.g., Barkham et al., 2006; Barkham, Stiles, & Shapiro, 1993; Krause et al., 1998). Growth mixture models (GMM) relax this single population assumption and allow for parameter differences across unobserved subgroups by implementing a categorical latent variable into a latent growth-modeling framework (e.g., Muthén, 2001, 2004). This technique assumes that individuals tend to cluster into distinct subgroups or patterns of patient change over time and allows the estimation of different growth curves for a set of subgroups. Such GMMs have been used to analyze psychotherapy data in naturalistic settings (Lutz et al., 2007; Stulz & Lutz, 2007; Stulz, Lutz, Leach, Lucock, & Barkham, 2007) and from randomized controlled trials (Lutz, Stulz, & Köck, 2009).

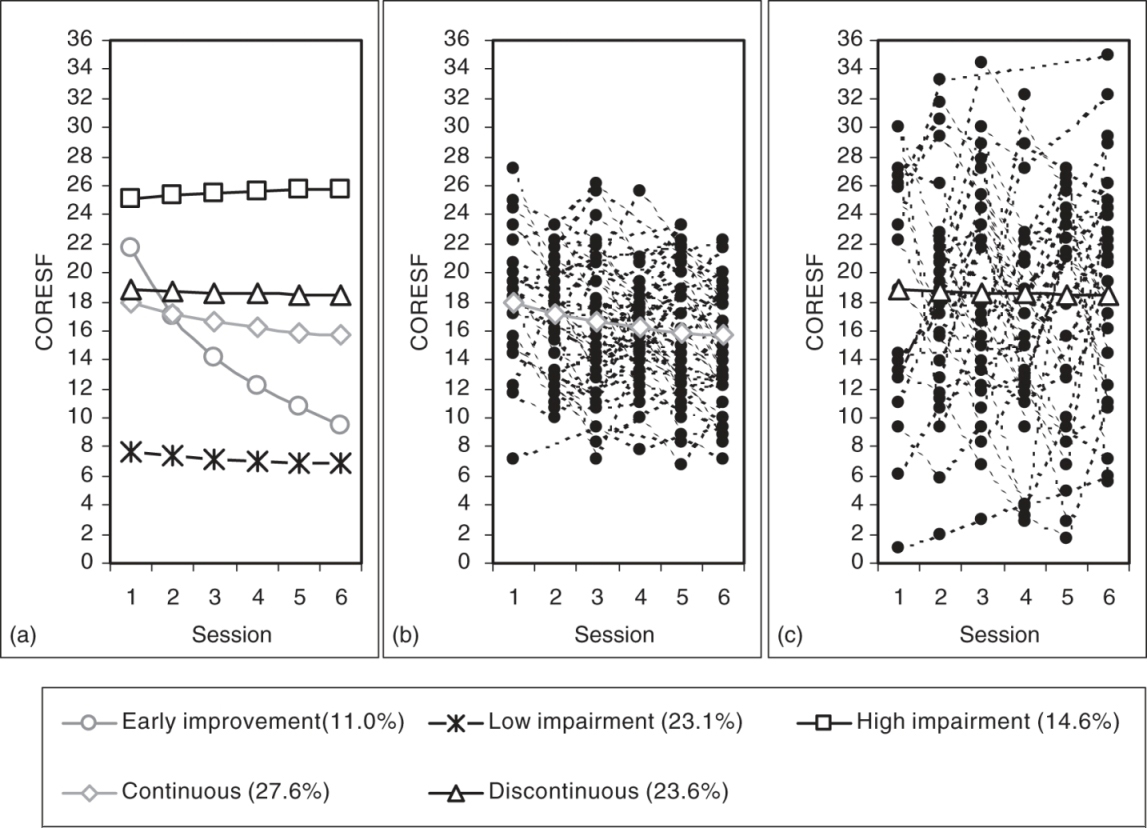

Figure 4.2 shows an application of a GMM in a sample of 192 patients drawn from the U.K. database mentioned earlier (Stulz et al., 2007). These patients completed the short-form versions of the Clinical Outcome in Routine Evaluation-Outcome Measure (CORE-SF; Cahill et al., 2006). In this example, shapes or patient clusters of early change (up to Session 6) have been identified to predict later outcome and treatment duration. Figure 4.2a displays the five different shapes of early change identified with the GMM. As can be seen, one cluster can be characterized by “early improvement” (11%). Patients in this cluster start with high scores on the CORE-SF but improve rapidly and substantially—more than 90% of those patients still show a substantial improvement at the end of treatment. A second cluster can be characterized by “high impairment” (23.1%) with little or no early patient change. The third cluster includes patients with “low impairment” (14.6%) who seem to have little or no early change until Session 6. The two remaining clusters in Figure 4.2a show two moderately impaired groups with similar average growth curves but, interestingly, very different individual treatment courses. Figures 4.2b and 4.2c display the plots of the actual individual treatment courses around the average growth curves in these two groups. Figure 4.2b presents the growth curves of the 27.6% of patients categorized into the “continuous” group who showed modest session-to-session variation in the early phase of treatment. These can be contrasted to the individual growth curves displayed in Figure 4.2c. These patients (23.6%) were categorized into the “discontinuous” group as they demonstrated fairly substantial session-to-session variation. When using the reliable change criterion (Jacobson & Truax, 1991) to evaluate pretreatment to posttreatment change in these two groups, results revealed a higher rate of reliably improved patients in the “discontinuous” group than in the “continuous” group (44% versus 19%). Importantly, however, treatment duration was not different between the two groups (M = 24.63 versus M = 25.55 sessions, n.s.). Conversely, the rate of reliably deteriorated patients was also higher in the “discontinuous” patient group relative to the “continuous” group (13% versus 0%). The results from this study suggest that instability during early treatment phases seems to result in higher chances for positive treatment outcomes but also higher risk for negative treatment outcomes.

To date, research on the advantages and disadvantages of rationally derived and empirical approaches has yielded mixed results. For example, Lambert, Whipple, et al. (2002) compared a rationally derived method to predict patient treatment failure with a statistical growth curve technique. The results showed broad equivalence between both methods but the empirical approach was somewhat more accurate. Other research also indicates that the empirically derived methods might be slightly superior (e.g., Lutz, Lambert, et al., 2006; Lutz, Saunders, et al., 2006). Irrespective of the selected approach (rationally derived or empirical), further research on differential patterns of change is necessary to clarify typical patterns for subgroups of patients as well as relating these empirical findings to clinical theories. Clinical theories that have a simple concept of treatment progress (i.e., a patient has a problem, a treatment approach is applied, the patient becomes healthy) appear oversimplistic and need to be adapted to take into account empirically defined change patterns. They could be further enhanced by considering related mediators and moderators causing different patterns of change that can then be used to guide or support clinical decisions (Kazdin, 2009).

Research on patterns of change is still in a preliminary phase. More studies are needed to further validate and replicate the findings obtained so far, and consideration needs to be given to the development of simpler methods. However, this research has the potential to provide therapists with decision guidelines that are individualized to each of their patients, especially early in treatment, as well as to identify and better understand the meaning of discontinuous treatment courses.

Provision of Feedback to Therapists and Patients

The above methods provide actuarial and predictive information on the course of treatment that has the potential to be used to enhance patient outcomes. At the practice level, the most apparent self-corrective function of routinely collected data derived from measurement systems is when it is used in the form of feedback to the practitioner, an area of research that has been espoused by the APA Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice (2006). Indeed, despite the small differences in predictive accuracy, research on feedback appears to be a powerful tool for enhancing outcomes, especially for patients who are at risk of treatment failure (e.g., Carlier et al., 2012; Lambert, 2010; Lutz, Böhnke, & Köck, 2011; Newnham & Page, 2010; Shimokawa et al., 2010). In this subsection, we consider the evidence base for using feedback routinely in clinical practice.

Recognizing Failing Patient Outcomes

The need for corrective feedback has been shown in comparisons between practitioners' and actuarial predictions of patient deterioration. Hannan et al. (2005) reported data from 48 therapists (26 trainees, 22 licensed) who were informed that the average rate of deterioration, defined as reliable deterioration on the OQ-45, was likely to be in the region of 8%. Given this base rate, the therapists were tasked with identifying, from a data set of 550 patients, how many would deteriorate by the end of treatment. Actual outcome data indicated that 40 clients (7.3%)—very close to the base rate—deteriorated by the end of therapy. Use of the actuarial predictive methods led to the identification of 36 of these 40 deteriorated cases. By contrast, the therapists predicted that a total of only 3 of the 550 clients would deteriorate, and only 1 of these had, in actuality, deteriorated at the end of therapy. Such data provides a powerful argument for investing in methods and procedures that enhance practitioners' treatment responses and planning in relation to patients who may be on course to fail in therapy.

Meta-Analyses and Reviews of Feedback

Carlier et al. (2012) carried out a review of 52 trials of feedback, 45 of which were based in mental health settings. The two largest subgroups of studies comprised those using global outcome measures (N = 24), of which 13 studies supported feedback, and depression measures (N = 11), of which 7 studies supported feedback. Overall, 29 of the 45 studies supported the superiority of providing feedback. Although providing a broad evidence base for feedback, this review lacked the precision afforded by a meta-analytic approach. A number of meta-analyses of outcomes feedback studies have been carried out (e.g., Knaup, Koesters, Schoefer, Becker, & Puschner, 2009; Lambert et al., 2003; Shimokawa et al., 2010). Lambert et al. (2003) completed a meta-analytic review of three large-scale studies2 in which the findings suggested that formally monitoring patient progress has a significant impact on clients who show a poor initial response to treatment. Implementation of a feedback system reduced client deterioration by between 4% and 8% and increased positive outcomes. Knaup et al. (2009) reviewed 12 studies3 and reported a small but significant positive short-term effect (d = .10; 95% CI .01 to .19). However, health gains were not sustained.

Lambert and Shimokawa (2011) carried out a meta-analysis of patient feedback systems relating to the Partners for Change Outcome Management System (PCOMS) and the OQ System. Three studies covering the PCOMS, drawn from two published reports (Anker, Duncan, & Sparks, 2009; Reese, Norsworthy, & Rowlands, 2009), indicated that the average client in the feedback group was better off than 68% of those in the treatment-as-usual group. Results indicated that patients in the feedback group had 3.5 times higher odds of experiencing reliable improvement while having half the odds of experiencing reliable deterioration. In terms of the OQ system, Lambert and Shimokawa (2011; see also Shimokawa et al., 2010) reanalyzed the combined data set (N = 6,151) from all six OQ feedback studies published to date.4 The three main comparisons were: no feedback, OQ-45 feedback, and OQ-45 plus clinical support tools (CST). Based on intent-to-treat analyses, the combined effects, using Hedges's g, of mean posttreatment OQ-45 scores for feedback only, patient/therapist feedback, and CST feedback were −0.28, –0.36, and −0.44 respectively. Shimokawa et al. (2010) concluded that all forms of feedback were effective in improving outcomes while reducing treatment failures (i.e., deterioration), with the exception of patient/therapist feedback for reducing treatment failures.

Even though this area of research is still relatively recent, research on feedback in clinical practice is already an internationally studied area of investigation. A program of research in Australia on feedback, subsequent to the above review and meta-analyses, has considered the impact of providing feedback given at a specific time-point during the course of treatment and at follow-up (Byrne, Hooke, Newnham, & Page, 2012; Newnham, Hooke, & Page, 2010). Newnham et al. (2010) employed a historical cohort design to evaluate feedback for a total of 1,308 consecutive psychiatric and inpatients completing a 10-day CBT group. All patients (inpatients and day patients), whose diagnoses were primarily depressive and anxiety disorders, completed the World Health Organization's Wellbeing Index (WHO-5; Bech, Gudex, & Johansen, 1996) routinely during a 10-day cognitive-behavioral therapy group. The first cohort (n = 461) received treatment-as-usual. The second cohort (n = 439) completed monitoring measures without feedback, and for patients in the third cohort (n = 408), feedback on progress was provided to clinicians and patients midway through the treatment period. Feedback was effective in reducing depressive symptoms in patients at risk of poor outcome. In a 6-month follow-up study, Byrne et al. (2012) compared the no-feedback cohort with the feedback cohort. Feedback was associated with fewer readmissions over the 6-month period following completion of the therapy program for patients who, at the point of feedback, were on track to make clinically meaningful improvement by treatment termination. Importantly, the authors argued that the findings suggested feedback could result in cost saving in addition to being associated with improved outcomes following treatment completion for patients deemed on track during therapy.

Besides recently published meta-analyses or reviews (e.g., Carlier et al., 2012; Shimokawa et al., 2010), several advances have also been made to adapt feedback systems to different patient populations and settings. For example, Reese, Toland, Slone, and Norsworthy (2010) carried out a randomized trial comparing feedback with treatment-as-usual for couple psychotherapy (N = 46 couples) within a routine service setting. The setting was a training clinic and the therapists were practicum trainees. At the level of the individual client, rates of clinically significant change for the feedback versus nonfeedback groups were 48.1% and 26.3% respectively while for reliable change the rates were 16.7% and 5.3% respectively. This advantage to the feedback condition also held when the couple was used as the unit of analysis, with 29.6% of couples in the feedback condition meeting clinically significant change versus 10.5% (no feedback). Respective rates for reliable change only were 14.8% versus 5.3%.

Bickman, Kelley, Breda, de Andrade, and Riemer (2011) carried out a randomized trial of feedback for youths within naturalistic settings comprising 28 services across 10 states.5 Services were randomly assigned to a control condition comprising access to feedback every 90 days, or an experimental condition comprising weekly access to feedback. Because many of the youths in the 90-day condition ended treatment prior to their practitioners accessing the feedback, the authors considered this condition as a no-feedback control. Effect size (Cohen's d) advantages to the feedback condition held regardless of the source of the outcome: .18 (youths), .24 (clinicians), and .27 (caregivers). The authors argued that although the effect sizes were small, they showed how outcomes could be improved without invoking new evidence-based treatment models. Feedback has also been evaluated in a nonrandomized study for substance-abuse patients (Crits-Cristoph et al., 2012). The design employed a two-phase implementation (Phase 1, weekly outcomes; Phase 2, feedback) with results showing advantages to the feedback phase. Crucially, however, these methods cannot be the sole basis for making clinical decisions—it can only be a support tool in aid of making clinical decisions, which always stays in the hands of the clinician.

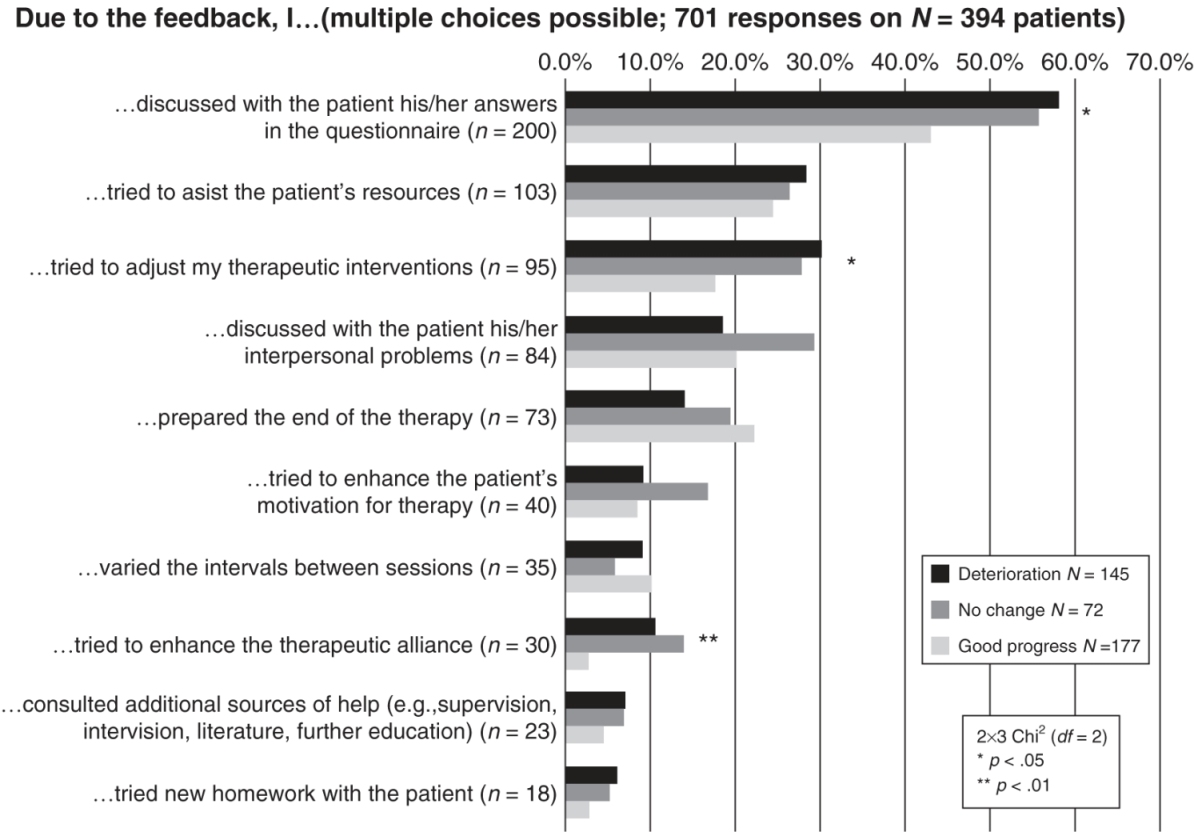

In the feedback study carried out in Germany that was reported earlier, therapists received feedback for their patients several times during the course of treatment. Table 4.1 and Figure 4.3 show how they responded to the feedback provided. On approximately 70% of occasions, therapists made some use of the feedback either by taking some action or by drawing some consequence concerning their treatment formulation. This is a high rate of action by therapists in response to the feedback information, especially given that most of the feedback was indeed positive feedback about the progress of patients. As can be seen in Figure 4.3, however, if patients showed negative progress early in treatment, then therapists, after receiving feedback, responded with a significant increase in the frequency of discussing the results with patients, adapting their treatment strategy, or trying to improve the therapeutic alliance (Lutz, Böhnke, Köck, & Bittermann, 2011). The positive evaluation from the patients participating in this study was also high, even when taking into account that not all of the patients responded. On almost all questions (see Table 4.1), the positive response rate exceeded 80%.

Table 4.1 Patients' Evaluations of the Quality Monitoring Project: Absolute Number and Percentage of Patients in the Respective Response Categories. Tables can be downloaded in PDF formats at http://higheredbcs.wiley.com/legacy/college/lambert/1118038207/pdf/c04_t01.pdf.

The above reviews, meta-analyses, and empirical reports provide an evidence-base that feedback to practitioners on patients shown not to be on-track enhances their outcomes across an increasing diversity of therapeutic modalities and patient populations. An early focus on university settings has broadened into wider samples of patient presentations. Research and development foci have moved to considering the most effective clinical support tools to aid the practitioner's decision making in how best to respond to a patient who is not on track.

In addition, there have been calls for the development of a theory for feedback (see Bickman et al., 2011; Carlier et al., 2012), a call similar to those seeking a theoretical model for the impact of routine outcome measurement (see Greenhalgh, Long, & Flynn, 2005). From a viewpoint of differing paradigms, this area of work shows how both practice-oriented research and trials methodology can yield a robust evidence base for one area of clinical activity. Moreover, it shows how the former can provide a platform for more intensive trial work that might enable a more fine-grained investigation into the mechanisms and theory-building of how feedback achieves better patient outcomes for those patients deemed not to be on-track.

Summary

Patient-focused research has provided the field with new insights about how patients change, with regard to the relationship between the amount of treatment received and outcome, as well as with respect to various patterns of progress, or lack thereof, experienced by different groups of clients. In addition, feedback on outcome progress has been found to be an effective tool to support treatment, especially for patients at risk of treatment failure (e.g., Carlier et al., 2012; Lambert, 2010; Lutz, Böhnke, & Köck, 2011; Newnham & Page, 2010; Shimokawa, et al., 2010). Furthermore, combining clinical support tools with such feedback has enhanced its effect (cf. Shimokawa et al., 2010). In this way research on outcomes feedback has two clinical implications: First, it allows therapists to track clinical progress on an individual level in order to determine, as early as possible, if a patient is moving in the right direction; and second, it has led to the delineation of decision support tools based on the variability and patterns in patient change. However it is important to emphasize, that clinically, outcome feedback can only serve as information to guide or support the decision-making process; the actual decisions of what goals or tasks to pursue, as well as when to continue, intensify, or terminate treatment remain to be made by the clinician and the patient.

Practice-Based Evidence

This section focuses on a further form of practice oriented research, namely practice-based evidence, which is a reversal of the term evidence-based practice. Together, these two terms generate a chiasmus6—evidence-based practice and practice-based evidence—that has the potential for yielding a rigorous and robust knowledge base for the psychological therapies (Barkham & Margison, 2007). As the term suggests, practice-based evidence is rooted in routine practice and aims to reprivilege the role of the practitioner as a central focus and participant in research activity (for a detailed description, see Barkham, Stiles, Lambert, & Mellor-Clark, 2010). Although the approach shares much in common with patient-focused research, the hallmarks of repeated measurement and a primary focus on patients that underpin patient-focused research are not sine qua non for practice-based evidence. Accordingly, practice-based evidence encompasses a broader, looser—less focused—collection of activities but takes its starting point as what practitioners do in everyday routine practice. At its heart, practice-based evidence is premised on the adoption and ownership of a bona fide measurement system and its implementation as standard procedure within routine practice. Implementation may be in the form of a pre- and posttherapy administration, repeated measurement intervals, or on a session-by-session basis. In terms of the yield of practice-based evidence, results can be considered at two broad levels: first, at the level of the individual practitioner whether working alone in private practice or within a community of practitioners in which the aim is to use data to improve their practice, and second, at a collective level in which the aim is to pool data such that it can contribute to and enhance the evidence base for the psychological therapies. With these two central aims, practice-based evidence delivers anew to the scientist-practitioner agenda.

This section provides illustrative examples of the yield of practice-based research by summarizing four key areas. First, a brief summary is provided of the development of selected measurement and monitoring systems, as representative of the field. Then illustrative findings are reported focusing on three successive levels of routine practice: the level of practitioners, then at the level of single services or providers, and finally, multiple services.

Measurement and Monitoring Systems

Although there are numerous features of practice-based evidence, the central component is the adoption and implementation of a measurement and monitoring system as part of routine practice. In contrast to stand-alone outcome measures, measurement and monitoring systems collect information on context and outcomes that are then used to improve practice and enhance the evidence base of the psychological therapies. The drive toward the adoption of measurement systems grew out of a developing trend for health insurance companies to seek evidence of outcomes and also from a growing frustration with the fragmented state regarding outcome measurement generally. The latter was illustrated in a review of 334 outcome studies from 21 major journals over a 5-year period (January 1983 to October 1988) that showed 1,430 outcome measures were cited, of which 851 were used only once (Froyd, Lambert, & Froyd, 1996). In routine practice, decisions on the selection of outcome measures were determined by factors such as those used in trials, which were invariably proprietary measures carrying a financial cost, or determined by idiosyncratic, historical, or local influences.7 These factors combined to militate against building a cumulative body of evidence derived from routine practice settings that could complement the evidence derived from trials methodology.

Measurement Systems

Measurement systems began to be developed in the 1990s with the first outcomes management system being named COMPASS (Howard et al., 1996; Sperry, Brill, Howard, & Grissom, 1996). The COMPASS system—comprising evaluations of current state of well-being, symptoms, and life functioning—together with subsequent research reported by Lueger et al. (2001) provided the basis for other outcomes management systems that drew upon the phase model as a conceptual foundation. These included the Treatment Evaluation and Management (TEaM) instrument (Grissom, Lyons, & Lutz, 2002) and the Behavioral Health Questionnaire (Kopta & Lowry, 2002).

Subsequently other measurement systems have been developed. Examples of systems developed include:

- The Outcome Questionnaire-45 and associated measures (OQ-45; Lambert, Hansen, & Harmon, 2010; Lambert, Lunnen, Umphress, Hansen, & Burlingame, 1994): The OQ Psychotherapy Quality Management System has, at its heart, the OQ-45, which assesses three main components: symptoms, especially depression and anxiety; interpersonal problems; and social role functioning. For more information, see Lambert, Hansen, and Harmon (2010); also www.oqmeasures.com

- The Treatment Outcome Package (TOP; Kraus & Castonguay, 2010; Kraus, Seligman, & Jordan, 2005; Youn, Kraus, & Castonguay, 2012): The TOP comprises 58 items that assess 12 symptom and functioning domains: work functioning, sexual functioning, social conflict, depression, panic, psychosis, suicidal ideation, violence, mania, sleep, substance abuse, and quality of life. In addition, the TOP measures demographics, health, stressful life events, treatment goals, and satisfaction with treatment. For further information, see www.OutcomeReferrals.com

- CelestHealth System for Mental Health and College Counseling Settings (CHS-MH; Kopta & Lowry, 2002): The Behavioral Health Measure (BHM) comprises four instruments that (a) assess complete behavioral health, (b) alert at the first session whether the client is at risk to do poorly in psychotherapy, and (c) evaluate the relationship between the therapist and the client. For more information, see www.celesthealth.com

- Partners for Change Outcome Management System (PCOMS; Miller, Duncan, Brown, Sparks, & Claud, 2003; Miller, Duncan, Sorrell, & Brown, 2005): The PCOMS comprises two 4-item scales: the Outcome Rating Scale (ORS; Miller et al., 2003) and the Session Rating Scale (SRS; Duncan & Miller, 2008). The ORS targets key components of mental health functioning while the SRS focuses on aspects of the therapeutic alliance. For more information, see www.heartandsoulofchange.com

- The Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation system (CORE; Barkham, Mellor-Clark, et al., 2010; Mellor-Clark & Barkham, 2006; Evans et al., 2002): The CORE-OM (Barkham et al., 2001; Evans et al., 2002) is a pan-theoretical outcome measure comprising 34 items tapping the domains of subjective well-being, problems, functioning, and risk. It lies at the heart of the broader CORE System, which provides contextual information on the provision of the service received by the patient (Mellor-Clark & Barkham, 2006). A family of measures is available for differing uses and for specific populations and translations are available in 20 languages. For more information, see www.coreims.co.uk

Outcomes systems have also been developed for specific populations and treatment modalities. For example, the Contextualized Feedback Intervention Training (CFIT) has been developed for youths (Bickman, Riemer, Breda, & Kelley, 2006) and the Integrative Problem Centered Metaframeworks for family therapy (IPCM; Pinsoff, Breunlin, Russell, & Lebow, 2011).

Although each outcome system differs on any number of particular features, they reflect a common aim, namely to measure and monitor patient outcomes routinely from which data is then used—fed back—to improve service delivery and patient outcomes. A resulting feature of practice-based evidence is, therefore, its ability to provide self-correcting information or evidence at the levels of practice and science within a short time frame. The following three subsections provide illustrative examples of the research yield at the levels listed earlier: practitioners, single services, and multiple services.

Practitioner Level: Effective Therapists and Therapist Effects

Reprivileging the therapist as a central focus of practice-based research redresses the balance in which the focus on treatments has long been dominant. Given that practitioners are the greatest resource—and cost—of any psychological delivery service, an equal investment in and prioritizing of practitioners is required to that already committed to the development and implementation of evidence-based treatments. The development of models of treatment based on the identification and observation of the practices of practitioners in the community who empirically obtain the most positive outcomes was a key recommendation of the APA Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice (2006). Research activity, especially trials, has predominantly used the patient rather than the practitioner as the primary unit upon which design features and analyses have been powered and premised. However, patients allocated to conditions within trials and observational studies are nested within therapists. This means that the outcomes of patients for any given therapist will be related to each other and likely different from those for patients seen by another (or other) therapist(s). Where a hierarchical structure is present but ignored in the analyses, assumptions about the independence of patient outcomes are violated, standard errors are inflated, p-values exaggerated, and the power of the trial reduced (e.g., Walwyn & Roberts, 2010).

A focus on what has come to be termed therapist effects developed following an article by Martindale (1978) and a subsequent meta-analysis in this area by Crits-Cristoph et al. (1991) as well as a critique of design issues (Crits-Christoph & Mintz, 1991). Wampold's (2001) text The Great Psychotherapy Debate followed, in which he concluded the impact of therapist effects as being in the region of 8%. Subsequent reanalyses of therapist effects in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program (TDCRP; Elkin et al., 1989) by Elkin, Falconner, Martinovitch, and Mahoney (2006), and Kim, Wampold, and Bolt (2006) highlighted the problems of low power and of attempting to determine therapist effects from trials that were originally designed to assess treatment effects. Elkin et al.'s (2006) advice was clear, namely that therapist effects would be best investigated using (very) large samples drawn from managed care or practice networks—that is, routine settings. Subsequent reports on therapist effects and effective practitioners have been consistent with this advice (e.g., Brown, Lambert, Jones, & Minami, 2005; Kraus, Castonguay, Boswell, Nordberg, & Hayes, 2011; Lutz, Leon, Martinovich, Lyons, & Stiles, 2007; Okiishi, Lambert, Nielsen, & Ogles, 2003; Okiishi et al., 2006; Saxon & Barkham, 2012; Wampold & Brown, 2005).

A series of studies utilizing data from PacifiCare Behavioral Health, a managed behavioral health care organization, focused on various aspects of therapist effects and effectiveness (Brown & Jones, 2005; Brown et al., 2005; Wampold & Brown, 2005). Brown et al. (2005) evaluated the outcomes of 10,812 patients treated by 281 therapists between January 1999 and June 2004. Mean residual change scores, obtained by multiple regression, were used to adjust for differences in case mix among therapists. Raw change scores as well as mean residualized change scores were compared between the 71 psychotherapists (25%) identified as highly effective and the remaining 75% of the sample. During a cross-validation period—used as a more conservative estimate accounting for regression to the mean—the highly effective therapists achieved an average of 53.3% more change in raw change scores than the other therapists. Results could not be explained by case mix differences in diagnosis, age, sex, intake scores, prior outpatient treatment history, length of treatment, or therapist training/experience.

Wampold and Brown (2005) analyzed data comprising a sample of 581 therapists and 6,146 patients, the latter completing a 30-item version of the OQ-45. Multilevel modeling yielded a therapist effect of 5%, somewhat lower than the 8% the authors reported as an estimate from clinical trials. To explain this counterintuitive finding, they reasoned that the restricted severity range employed in trials, thereby leading to a more homogeneous sample, yielded a smaller denominator when calculating the therapist effect.

The above studies focused on overall therapist effects. However, it might be that therapists are differentially effective depending on the specific focus of the clinical presentation. This question was addressed in an archive data set comprising services contracted with Behavioral Health Laboratories (BHL). Kraus et al. (2011) analyzed the outcomes of 6,960 patients seen by 696 therapists (i.e., 10 clients per therapist) in the context of naturalistic treatment in which the TOP was used. The specific aim was to investigate the effectiveness across the 12 domains in the TOP. With the exception of Mania, which had a low base rate, the reliability of the remaining 11 domains ranged from .87 to .94. Therapists were defined as effective, harmful, or neither based on categories of change using the criterion of the reliable change index (RCI) as follows: effective therapist if their average client reliably improved, harmful if their average client reliably deteriorated, and ineffective/unclassifiable if their average client neither improved nor worsened. Hence therapists were deemed effective or otherwise according to average change scores on each domain of the TOP, where a specific therapist could be classified as effective in treating depression (for example) and ineffective or harmful in treating substance abuse. In all, 96% of therapists were classified as effective in treating at least one TOP domain while classifications varied widely across 11 of the 12 domains (Mania was excluded due to low base rate.) Effective therapists displayed large positive treatment effects across domains (Cohen's d = 1.00 to 1.52). For example, in the domain of depression 67% of therapists were rated as effective (i.e., their average patient achieved reliable change in the domain of depression) with an average treatment effect size of 1.41. Harmful therapists demonstrated large, negative treatment effect sizes (d = −0.91 to −1.49). An important finding was that therapist domain-specific effectiveness correlated poorly across domains, suggesting that therapist competencies may be specific to domains or disorders rather than reflecting a core attribute or underlying therapeutic skill construct. This study highlights the distinction between seeking and analyzing competencies in specific domains of patient experience versus averaging the therapist effects by analyzing total scores across their patients. For a discussion of the advantages and limitations of these two approaches in outcome monitoring, see McAleavey, Nordberg, Kraus, and Castonguay (2012).

The notion that some therapists are more effective than others caught attention with the use of the term supershrink (Ricks, 1974) in relation to a report on a very effective practitioner, with Bergin and Suinn (1975) labeling its opposite as pseudoshrink. Okiishi and colleagues addressed the concept of the exceptional therapist in consecutive studies (Okiishi et al., 2003, 2006). They utilized data from a large data pool in a university counseling center in which clients completed the OQ-45 on a regular basis. Both studies selected cases in which there were at least 3 data points. In addition, the initial study sampled practitioners who had seen a minimum of 15 clients each yielding a target sample of 56 therapists and 1,779 clients. This sample was extended in the second study and the criterion for the number of clients seen per therapist was increased to 30, yielding a target sample of 71 therapists and 6,499 clients (Okiishi et al., 2006). In this latter study, analyses focused on the average ranking of these 71 therapists based on their combined rankings according to their effectiveness (i.e., patient outcomes) and efficiency (i.e., number of sessions delivered). The authors examined and contrasted the top and bottom 10% of therapists (i.e., the ends of the distribution). The seven most effective therapists saw their clients for an average of 7.91 sessions, with clients making gains of 1.59 OQ points per session and resulting in a pre-posttherapy average change score on the OQ-45 of 13.46 (SD = .76). By contrast, the seven least effective therapists saw their clients for an average of 10.59 sessions, making gains of .48 OQ points per session and a pre-postaverage OQ-45 change score of 5.33 (SD = 1.66). Hence, these analyses suggested the most effective therapists achieved threefold gains for their patients compared with the least effective. Classifying clients seen by these most- and least-effective therapists according to the clinical significance of their change on pre-posttherapy scores (Jacobson & Truax, 1991; recovered, improved, no change, or deteriorated) showed therapists at the top end of the distribution had an average recovery rate of 22.4% with a further 21.5% improved while therapists at the bottom end of the distribution had a recovery rate of 10.61% with a further 17.37% improved. In addition, bottom-ranked therapists had a 10.56% deterioration rate while the equivalent percentage was 5.20% for top-ranked therapists.

The finding that some therapists achieve appreciably better outcomes than average highlights the naturally occurring variability in outcomes for therapists. For example, Saxon and Barkham (2012) investigated this phenomenon using a large U.K. data set in which clients completed the CORE-OM. Like Okiishi et al. (2006), the authors employed the recommendation of Soldz (2006) with each practitioner seeing a minimum of 30 patients. They investigated the size of therapist effects and considered how this therapist variability interacted with key case-mix variables, in particular, patient severity and risk. The study sample comprised 119 therapists and 10,786 patients. Multilevel modeling, including Markov chain Monte Carlo procedures, was used to derive estimates of therapist effects and to analyze therapist variability.

The model yielded a therapist effect of 7.8% that reduced to 6.6% by the inclusion of therapist caseload variables. Effects for the latter rate varied between 1% and 10% as patients' scores reflecting their levels of subjective well-being, symptoms, and overall functioning became more severe. The authors concluded that a significant therapist effect existed, even when controlling for case mix, and that the effect increased as patient severity increased. Patient recovery rates, using Jacobson's criteria for reliable and clinically significant improvement, for individual therapists ranged from 23.5% to 95.6%. Overall, two-thirds of therapists (n = 79, 66.4%) could be termed as average in that the 95% confidence intervals surrounding their residual score crossed zero and could not, therefore, be considered different from the average therapist. The mean patient recovery rate for this group of therapists was 58.0%. For 21 (17.7%) therapists their outcomes were better than average with a mean patient recovery rate of 75.6%, while for 19 (16.0%) therapists their outcomes for patients were poorer than average with a mean recovery rate of 43.3%.

The studies by Okiishi et al. (2003, 2006) as well as by Saxon and Barkham (2012) highlight the considerable differences that exist in therapist effectiveness when comparing the two ends of the distribution of therapists. Although the majority of therapists cannot be differentiated from each other (i.e., are not significantly different from the average), differences between the extremes are real and meaningful for patients and, when considered in relation to the population of therapists as a whole, have significant implications for professional policy and practice. Variability is a phenomenon that is inherent in all helping professions and it would seem important to understand the extent of this phenomenon in routine practice. Developing supportive ways of providing feedback at both the individual therapist and organizational level is an area that needs attention.

Single Service Level and Benchmarking in Routine Settings

A service or professional center providing psychological therapy will have, as a priority, a focus on its effectiveness, efficiency, quality, and cost, while patients, as consumers, will increasingly want to be assured they are seeking help from a professional agency (i.e., mental health center or service) that is effective. Current work has built on ideas dating back to the seminal work of, for example, Florence Nightingale (1820–1910)—who suggested a simple 3-point health-related outcome measure for her patients of relieved, unrelieved, and dead—and Ernest Codman (1869–1940), who implemented an “end results cards” system for collating the outcomes and errors on all patients in his hospital in Boston. However, while using a measurement system provides data on the actual service, practice data requires a comparator or standard against which to locate its own outcomes or other data. This requirement has led to the practice of benchmarking service data (for a summary, see Lueger & Barkham, 2010). Benchmarking can either involve comparisons with similar types of service (i.e., outcomes of other practice-based studies) or against the results of trials (i.e., assumed to be the gold standard). Persons, Burns, and Perloff (1988) provided an early example in which they compared cognitive therapy as delivered in a private practice setting with outcomes from two trials (Murphy, Simons, Wetzel, & Lustman, 1984; Rush, Beck, Kovacs, & Hollon, 1977). The authors concluded that their results were broadly consistent with those from the trials. Subsequently, although better described as effectiveness studies rather than practice-based, Wade, Treat, and Stuart (1998) as well as Merrill, Tolbert, and Wade (2003) provided examples of research that transported treatments into more routine settings and evaluated them using a benchmarking approach. Subsequent methods for determining benchmarks have been devised that enable comparisons with trials (see Minami, Serlin, Wampold, Kircher, & Brown, 2006; Minami, Wampold, Serlin, Kircher, & Brown, 2007).

Benchmarking as an approach has burgeoned across a range of service settings and patient populations whereby routine services and/clinics have been able to establish their relative effectiveness. Examples include the following: service comparisons year-on-year (e.g., Barkham et al., 2001; Gibbard & Hanley, 2008) and with national referential data (Evans, Connell, Barkham, Marshall, & Mellor-Clark, 2003), OCD in childhood (Farrell, Schlup, & Boschen, 2010) and in adults (Houghton, Saxon, Bradburn, Ricketts, & Hardy, 2010), group CBT (e.g., Oei & Boschen, 2009), psychodynamic-interpersonal therapy (e.g., Paley et al., 2008), CBT with adults (e.g., Gibbons et al., 2010; Westbrook & Kirk, 2005) and with adolescents (e.g., Weersing, Iyengar, Kolko, Birmaher, & Brent, 2006). These benchmarking studies, which are only a sample, all share a common aim of providing an evidence base regarding the effectiveness of interventions as delivered in routine services. But it is also possible to see specific themes by which studies can be grouped. These include, underrepresented approaches (e.g., non-CBT interventions), new or innovative interventions, and extensions to broader populations and/or settings.

In terms of underrepresented approaches, Gibbard and Hanley (2008), for example, reported a study employing data from a single service over a 5-year period using the CORE-OM, in which counselors delivered person centered therapy (PCT). In this study, a total of 1,152 clients were accepted into therapy and the data sample comprised 697 clients who completed CORE-OM forms at both pre- and posttherapy (i.e., 63% completion rate). Rates for reliable improvement8 calculated for each year separately ranged between 63.1% (second year) and 73.5% (third year) with an overall rate for the 5-year period of 67.7%. The authors concluded that PCT was an effective intervention in primary care. Moreover, based on a smaller subset of data (n = 196), they concluded that PCT was also effective for moderate to severe problems of longer duration.

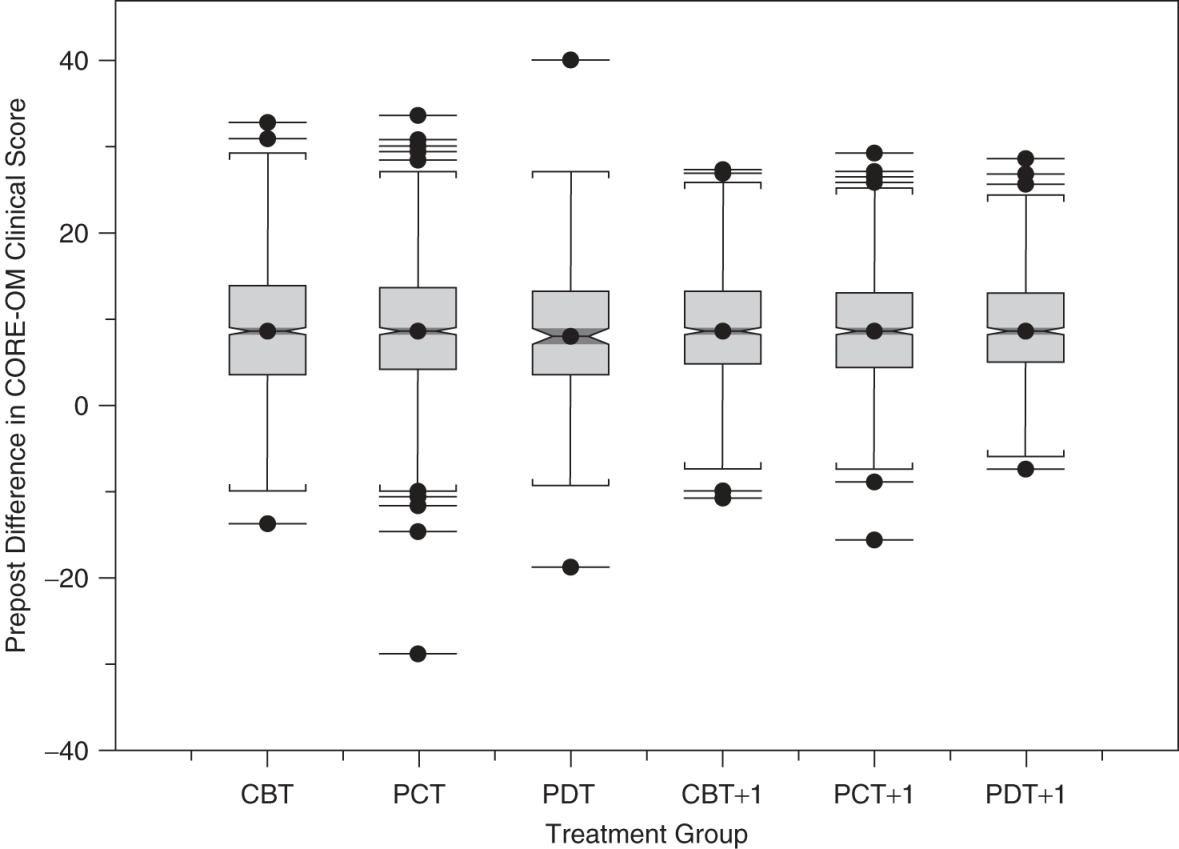

Similarly, Paley et al. (2008) reported the outcomes of a single service delivering psychodynamic-interpersonal (PI) therapy. Full data was available for 62 of the 67 patients who were referred by either their general practitioner or psychiatrist to receive psychotherapy. Outcomes were obtained for the CORE-OM and the BDI and were then benchmarked against data reported from other practice-based studies. The pre-posttherapy BDI effect size for the PI service was .76 compared with a benchmark of .73 derived from CBT delivered at the Oxford-based CBT clinic (Westbook & Kirk, 2005). When only those clients who initially scored above clinical threshold were considered, the pre-posttherapy effect size for PI therapy was .87 compared with an effect size of 1.08 for the CBT routine clinic. Rates of reliably and significant improvement (Jacobson & Truax, 1991) were identical for both services at 34%, indicating broad equivalence in outcomes of the contrasting therapeutic approaches in routine settings. Both these studies illustrate the effectiveness of interventions in routine practice settings that are underrepresented when national bodies determine treatment interventions of first choice. Addressing this issue requires either the necessary funding to secure an evidence-base sufficient to satisfy national bodies (e.g., NICE) or, more radically, a reevaluation of how we define the nature of evidence.