Chapter 21

Ten (Plus One) Popular Catholic Saints

IN THIS CHAPTER

Discovering the stories behind beloved Catholic heroes

Discovering the stories behind beloved Catholic heroes

Getting inspired by their faith

Getting inspired by their faith

Catholics do not worship saints, but the saints are near and dear to Catholic hearts. Catholics respect and honor the saints and consider them to be the heroes of the Church. The Church emphasizes that they were ordinary people from ordinary families, and they were totally human. They weren’t born with halos around their heads, and they didn’t always wear a smile, either. What separated them from those who weren’t given the title of saint was that they didn’t despair; they kept right on honing their souls for heaven come hell or high water. Get the full Catholic perspective on saints in Chapter 18.

In this chapter, we share some tidbits about the lives of 11 such ordinary people who became popular saints. We’ve listed them in chronological order.

St. Peter (died around A.D. 64)

The brother of Andrew and the son of Jona, St. Peter was originally called Simon. He was a fisherman by trade. Biblical scholars believe that Peter was married because the Gospel speaks of the cure of his mother-in-law (Matthew 8:14; Luke 4:38). But whether he was a widower at the time he met Jesus, no one knows for sure. Scholars believe it’s likely that his wife was no longer alive because after the Crucifixion, Resurrection, and Ascension of Christ, Peter became head of the Church (the first pope) and had a busy schedule and itinerary. He also never mentioned his wife in his epistle. (An epistle is a pastoral letter written by one of the apostles and found in the New Testament, immediately after the Four Gospels and the Book of Acts and just before the Apocalypse or Book of Revelation. These letters were composed to give the early Christian communities encouragement and/or instruction.)

According to the Bible, Andrew introduced Peter to Jesus and told his brother, “We have found the Messiah!” (John 1:41). When Peter hesitated to follow Jesus full time, Jesus came after him and said, “I will make you fishers of men” (Matthew 4:19).

The faithful believe that Peter’s confession of faith made him stand out in the crowd, even among the 12 apostles. Matthew 16:13–16 tells the story: Jesus posed the question, “Who do men say that the Son of man is?” The other 11 merely reiterated what they’d heard others say: “Some say John the Baptist, others say Elijah, and others say Jeremiah or one of the Prophets.” Jesus then asked directly, “But who do you say that I am?” Only Peter responded, “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.” His answer received the full approval of Jesus, which is why Peter was made the chief shepherd of the Church and head of the apostles. Matthew 16:17–19 says:

“Blessed are you, Simon Bar-Jona! For flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father who is in heaven. And I tell you, you are Peter (Petros), and on this rock (petra) I will build my church, and the powers of death shall not prevail against it. And I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatsoever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.”

The Greek language, in which the Gospel was first written, uses the word Petros as the proper first name of a man and the word petra to refer to a rock. Peter means rock, but in Greek, as in most other languages except English, nouns have gender. Petra is the word for rock, and it’s feminine, so you wouldn’t call a man petra no matter how “strong as a rock” he may be. We believe that had Jesus used petra instead of petros for Peter, the other apostles and disciples would never have let Peter live it down because using a feminine ending would have been inappropriate. (These were sailors and fishermen, after all.)

The Greek language, in which the Gospel was first written, uses the word Petros as the proper first name of a man and the word petra to refer to a rock. Peter means rock, but in Greek, as in most other languages except English, nouns have gender. Petra is the word for rock, and it’s feminine, so you wouldn’t call a man petra no matter how “strong as a rock” he may be. We believe that had Jesus used petra instead of petros for Peter, the other apostles and disciples would never have let Peter live it down because using a feminine ending would have been inappropriate. (These were sailors and fishermen, after all.)

St. Paul of Tarsus (10–67 A.D.)

Saul of Tarsus was a zealous Jew who also had Roman citizenship because of the place of his birth. A member of the Pharisees, Saul considered Christians to be an extreme danger to Judaism. He saw them as more than heretics; they were blasphemers for considering Jesus to be the Son of God.

He was commissioned by the Sanhedrin (the religious authority in Jerusalem) to hunt down, expose, and when necessary eliminate Christians to preserve the Hebrew religion. Things changed dramatically, however, and the world has never been the same since.

One day on the road to Damascus, he was thrown down to the ground, and a voice called out, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” (Acts 9:4). The voice belonged to Jesus of Nazareth, who had already died, risen, and ascended to heaven. Saul realized he had been persecuting Christ by persecuting those who believed in Christ. Opposing the followers of Jesus was in essence opposing Jesus himself.

Blinded by the event, Saul continued from Jerusalem to Damascus, but not to persecute the Christians — rather to join them. God turned an enemy into His greatest ally. He now called himself Paul and began to preach the Gospel widely in the ancient world. He made three journeys throughout Greece and Asia Minor before his final journey to Rome as a prisoner of Caesar.

Being a Roman citizen, he was exempt from death by crucifixion (unlike St. Peter, who was crucified upside-down in Rome around A.d. 64).The Emperor had him executed by the sword (beheading) around A.d. 67 Both St. Peter and St. Paul are considered co-patron saints of the city of Rome where they were both martyred.

St. Paul wrote 13 epistles of the New Testament (Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, 1 and 2 Thessalonians, 1 and 2 Timothy, Titus, and Philemon). Many believed he had also authored the letter to the Hebrews, but that is now in debate.

Known as the missionary to the Gentiles, the once fervent Jew converted to Christianity and preached to the non-Jewish peoples of the ancient world. He advocated a policy of not compelling Gentiles to embrace Judaism, especially the dietary laws and circumcision, if they wanted to go directly from paganism to Christianity.

His relics are venerated in one of the four major basilicas in Rome, St. Paul Outside the Walls.

St. Dominic de Guzman (1170–1221)

St. Dominic was a contemporary of St. Francis of Assisi, whom we discuss next. The faithful believe that when St. Dominic’s mother, Joanna of Aza (the wife of Felix de Guzman) was pregnant, she had a vision of a dog carrying a torch in his mouth, which symbolized her unborn son who would grow up to become a hound of the Lord. The name Dominic was thus given to him, because in Latin Dominicanis can be Domini + canis (dog or hound of the Lord).

Dominic lived at a time when some followers of Christ believed only in his divine nature; they denied his human nature. These believers couldn’t accept a god who would suffer and die for humankind’s sins. Their beliefs were called the Albigensian heresy. Catholics believe that Mary gave the rosary to Dominic to help him conquer Albigensianism. Dominic promoted devotion to Mary and the practice of praying the Rosary (see Chapter 16) around Western Europe.

Dominic also established the Order of Friars Preachers (shortened to Order of Preachers), called the Dominicans. Along with their brother Franciscans (whom we discuss in the next section), the Dominicans re-energized the Church in the 13th century and brought clarity of thought and substantial learning to more people than ever before. The motto of St. Dominic was veritas, which is Latin for truth.

St. Francis of Assisi (1181–1226)

The son of a wealthy cloth merchant, Pietro Bernadone, Francis was one of seven children. Today, people would say that he grew up with a silver spoon in his mouth.

Even though he was baptized Giovanni, his father later changed his name to Francesco (Italian for Francis or Frank). He was handsome, courteous, witty, strong, and intelligent, but very zealous. He liked to play hard and fight hard like most of his contemporaries. Local squabbles between towns, principalities, dukedoms, and so on were rampant in Italy in the 12th century. Francis was a playboy of sorts but wasn’t a nasty or immoral one. After spending a year in captivity with the rival Perugians, who fought their neighbors the Assisians, Francis decided to cool his jets for a while. One day, he met a poor leper on the road whose stench and ugliness repulsed him at first. Remorseful, Francis turned around, got off his horse, embraced the beggar and gave him clothes and money. The man immediately disappeared, and Francis believed it was Christ visiting him as a beggar. He then went to visit the tomb of St. Peter in Rome, where he gave all his worldly possessions — money, clothes, and belongings — to the poor and put on the rags of a poor man himself. Lady Poverty was to be his bride.

His dad wasn’t happy about the embarrassment Francis caused, so he dragged, beat, and locked up Francis in attempts to make him come to his senses. His mother helped Francis escape to a bishop friend of his, but his father soon found him. Because he was on church property, however, Signor Bernadone couldn’t violate the sanctuary and force his son home. Francis took what little clothing he had from home still on his person and threw it at his father and said: “Hitherto I have called you my father on earth; henceforth I desire to say only ‘Our Father who art in Heaven.’”

Sometime around 1210 he started his own religious community called the Order of Friars Minor (OFM), which today is known as the Franciscans. They took vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, but unlike the Augustinian and Benedictine monks who lived in monasteries outside the villages and towns, St. Francis and his friars were not monks but mendicants, which means that they begged for their food, clothes, and shelter. What they collected they shared among themselves and the poor. They worked among the poor in the urban areas.

Catholics believe that in 1224, St. Francis of Assisi was blessed with the extraordinary gift of the stigmata, the five wounds of Christ imprinted on his own body.

St. Francis of Assisi loved the poor and animals, but most of all he loved God and his Church. He wanted everyone to know and experience the deep love of Jesus that he felt in his own heart. He is credited with the creation of two Catholic devotions: the Stations of the Cross (see Chapter 16) and the Christmas crèche.

St. Anthony of Padua (1195-1231)

St. Anthony was born as Ferdinand, son of Martin Bouillon and Theresa Tavejra. At the age of 15 he joined an order of priests called the Canons Regular of St. Augustine. Later he transferred to the newly formed Order of Friars Minor (OFM), or Franciscans, where he took the religious name of Anthony.

He is famous for being an effective orator. Anthony’s sermons were so powerful that many Catholics who strayed from the faith and embraced false doctrines of other religions would repent after hearing him. This skill led to his nickname, “Hammer of Heretics.”Anthony got so disgusted one day with the locals who obstinately refused to listen to his preaching that he went to the river and started preaching to the fish. So many fish gathered at the bank that the townsfolk got the message and began to heed his instructions.

St. Anthony is invoked as the patron saint of lost items. On one occasion, a little boy appeared in the town square, apparently lost. Anthony picked him up and carried him around town looking for the boy’s family. They went to house after house, but no one claimed him. At the end of the day, Anthony approached the friary chapel. The boy said, “I live there.” Once in the oratory, the child disappeared. It was later discerned that the child was in fact Jesus. Since then, Catholics invoke St. Anthony whenever they lose something, even car keys or eyeglasses.

St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274)

The greatest intellect the Catholic Church has ever known was born of a wealthy aristocratic family, the son of Landulph, Count of Aquino, and Theodora, Countess of Teano. Thomas’s parents sent him at the age of five, which was customary, to the Benedictine Abbey of Monte Cassino. It was hoped that if he didn’t show talents suited for becoming a knight or nobleman, he could at least rise to the rank of abbot or bishop and thus add to his family’s prestige and influence.

However, ten years later, Thomas wanted to join a new mendicant order, which was similar to the Franciscans in that it didn’t go to distant monasteries but worked in urban areas instead. The new order was the Order of Preachers (O.P.), known as Dominicans.

His family had other ideas, putting him under house arrest for two years in an effort to dissuade his Dominican vocation. He didn’t budge. While captive, he read and studied assiduously and learned metaphysics, Sacred Scripture, and the Sentences of Peter Lombard. (Lombard was the premier theologian of the 12th century, and his “sentences” comprised a theology primer.) His parents finally relented, and at the age of 17 he was put under the tutelage of St. Albert the Great, the pride of the Dominican intelligentsia. Albert was the first to bridge the gap between alchemy and chemistry, from superstition to science. Thomas learned much from his academic master.

Thomas Aquinas is best known for two things:

- His monumental theological and philosophical work, the Summa Theologica, covers almost every principal doctrine and dogma of his era. What St. Augustine and St. Bonaventure were able to do with the philosophy of Plato regarding Catholic Theology, St. Thomas Aquinas was able to do with Aristotle. (Philosophy has been called the handmaiden of theology because you need a solid philosophical foundation in order to understand the theological teachings connected to it.) The Catechism of the Catholic Church has numerous references to the Summa some 800 years later.

- He composed hymns and prayers for Corpus Christi at the request of the pope, and he wrote Pange Lingua, Adoro te Devote, O Salutaris Hostia, and Tantum Ergo, which is often sung at Benediction. (See Chapter 19 for more on Benediction.)

He died while on the way to the Second Council of Lyons, where he was to appear as a peritus (expert). For more on St. Thomas Aquinas, see Chapters 3, 8, 9, 14, and Appendix A.

St. Patrick of Ireland (387–481)

There are many stories surrounding the origin of St. Patrick. The most credible says that he was born in Britain during Roman occupation and was a Roman citizen. His father was a deacon, and his grandfather was a priest in the Catholic Church. Much of what we know about Patrick we get from his autobiography, The Confessions. At 16 years of age, he was abducted by pirates and taken to Ireland as a slave. The Celtic pagan tribes who lived in Ireland were Druids. After several years he escaped and returned to Britain, but with a love for the people of Ireland.

Patrick did not follow in his dad’s footsteps and become a Roman soldier. He felt called to serve the Lord and His Church by being ordained a priest. He went back to Ireland to convert the people who had originally kidnapped him. While there, he became a bishop and was very successful in replacing paganism with Christianity.

Legend has it that he explained the mystery of the Holy Trinity (Three Persons in One God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit) to the Irish king by using a shamrock. Folklore also has him driving out all the snakes from Ireland.

St. Thérèse of Lisieux (1873–1897)

Francoise-Marie Thérèse, the youngest of five daughters, was born on January 2, 1873. When she was four, her mother died and left her father with five girls to raise on his own. Two of her older sisters joined the Carmelite order of nuns, and Thérèse wanted to join them when she was just 14 years old. The order normally made girls wait until they were 16 before entering the convent or monastery, but Thérèse was adamant. She accompanied her father to a general papal audience of His Holiness Pope Leo XIII and surprised everyone by throwing herself before the pontiff, begging to become a Carmelite. The wise pope replied, “If the good God wills, you will enter.” When she returned home, the local bishop allowed her to enter early. On April 9, 1888, at the age of 15, Thérèse entered the Carmelite monastery of Lisieux and joined her two sisters. On September 8, 1890, she took her final vows. She showed remarkable spiritual insights for someone so young, but it was due to her childlike (not childish) relationship with Jesus. Her superiors asked her to keep memoirs of her thoughts and experiences.

At the age of 23, she coughed up blood and was diagnosed with tuberculosis. She lived only one more year, and it was filled with intense physical suffering. Yet it’s said that she did so lovingly, to join Jesus Christ on the cross. She offered up her pain and suffering for souls that might be lost, so they could come back to God. Her little way consisted of, in her own words, “doing little things often, doing them well, and doing them with love.” She died on September 30, 1897.

Despite the fact that she lived such a short and cloistered life, having never left her monastery after she took her vows, she was later named Patroness of the Foreign Missions. The reason was that during World War I, many soldiers who were wounded in battle and recuperating in hospitals — as well as those who were in the trenches awaiting their possible death — read her autobiography, and it changed their hearts. Many who had grown cold or lukewarm in their Catholic faith wanted to imitate St. Thérèse of Lisieux, who was also known as the Little Flower, and become a little child of God.

St. Pio of Pietrelcina (1887–1968)

Padre Pio was born on May 25, 1887, in Pietrelcina, Italy. Because he showed evidence of having a priestly vocation early in his youth, his father went to the United States to make enough money so Francesco (his baptismal name) could attend school and seminary. At the age of 15, he took the vows and habit of the Friars Minor Capuchin and assumed the name of Pio in honor of Pope St. Pius V, patron of his hometown. On August 10, 1910, he was ordained a priest. Catholics believe that less than a month later, on September 7, he received the stigmata, just like St. Francis of Assisi.

During World War I, he served as a chaplain in the Italian Medical Corps. After the war, news spread about his stigmata, which stirred up some jealous enemies. Because of false accusations that were sent to Rome, he was suspended in 1931 from saying public Mass or from hearing confessions. Two years later, Pope Pius XI reversed the suspension and said, “I have not been badly disposed toward Padre Pio, but I have been badly informed.”

In 1940, he convinced three physicians to come to San Giovanni Rotundo to help him erect a hospital, Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza (House for the Relief of Suffering). It took until 1956 to finally build the hospital due to World War II and slow donations, but it eventually came to pass.

Catholics believe that he was able to read souls, meaning that when people came to him for confession, he could immediately tell if they were lying, holding back sins, or truly repentant. One man reportedly came in and confessed only that he was unkind from time to time, and Padre Pio interjected, “Don’t forget when you were unkind to Jesus by missing Mass three times this month, either.”

He became so well loved all over the region and indeed all over the world that three days after his death on September 23, 1968, more than 100,000 people gathered at San Giovanni Rotundo to pray for his departed soul.

Pope St. John XXIII (1881–1963)

Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli was the third of 13 children and grew up in the North of Italy near Bergamo. His family was poor but devout. He was ordained a priest in 1904. Angelo was an army chaplain in World War I, secretary to his diocesan bishop, and spiritual director at the local seminary.

He became a bishop in 1925 and served as an apostolic delegate to Turkey and Greece, and eventually Papal Nuncio (Ambassador) to Paris. In 1953 he was made the Cardinal Archbishop of Venice.

When Pope Pius XII died in 1958, Roncalli was elected his successor after 11 ballots on October 28, 1958, at age 76. He took the name John XXIII. Many cardinals thought he would be a “caretaker pope” after the 19-year reign of Pius. John XXIII surprised everyone by convening an Ecumenical Council (Vatican II) from 1962–1965. It was the first council since the First Vatican Council ended in 1870.

Pope St. John XXIII was a very popular pope even though he did not live long, dying during the sessions of Vatican II from stomach cancer. Pope St. John Paul II beatified him in 2000, and Pope Francis canonized him in 2014.

Pope St. John Paul II, the Great (1920–2005)

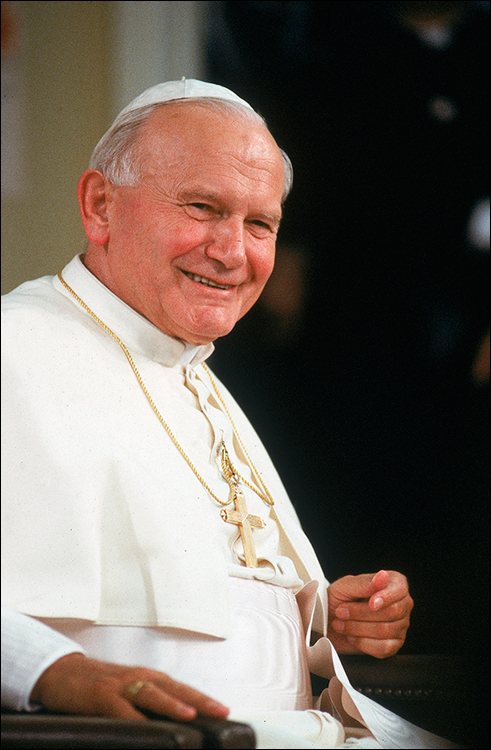

Pope John Paul II, a highly visible Catholic of the modern era, was the 264th pope and the first non-Italian pope in more than 450 years (see Figure 21-1).

He was born Karol Józef Wojtyla on May 18, 1920, in Wadowice, Poland, the son of Karol Wojtyla and Emilia Kaczorowska. His mother died nine years after his birth, followed by his brother, Edmund Wojtyla, a doctor, in 1932, and then his father, a noncommissioned army officer, in 1941.

The Nazi invasion and occupation of Poland in 1939 forced Karol to work in a stone quarry from 1940 to 1944 and then in a chemical factory to prevent his deportation to Germany. In 1942, he felt called to the priesthood and joined the clandestine underground seminary of Adam Stefan Cardinal Sapieha, Archbishop of Kraków. He was ordained a priest on November 1, 1946. He was sent to Rome, and he earned a doctorate in theology from the Dominican seminary of the Angelicum in 1948.

For the next ten years, Karol taught as a professor of theology at Catholic colleges and universities in Poland. On July 4, 1958, Pope Pius XII appointed him an Auxiliary Bishop of Kraków. In 1964, Pope Paul VI promoted him to Archbishop of Kraków and then made him a cardinal three years later. He was present at Rome for the Second Vatican Council, which met from 1962 to 1965.

Pope Paul VI died in August 1978. Albino Cardinal Luciani was elected his successor and took the name John Paul to honor Paul VI and John XXIII, the two popes of Vatican II. But John Paul I lived only a month. So on October 16, 1978, Karol Cardinal Wojtyla was elected bishop of Rome and took the name John Paul II.

Pope St. John Paul II wrote 84 combined encyclicals, exhortations, letters, and instructions to the Catholic world, beatified 1,338 people, canonized 482 saints, and created 232 cardinals.

He traveled 721,052 miles (1,243,757 kilometers), the equivalent of 31 trips around the globe. During these journeys, he visited 129 countries and 876 cities. While home in Rome, he spoke to more than 17.6 million people at weekly Wednesday audiences.

At 5:19 p.m. on May 13, 1981, a would-be assassin, Mehmet Ali Agca, shot Pope John Paul II and nearly killed him. A five-hour operation and 77 days in the hospital saved his life, and the pope returned to his full duties a year later.

Fluent in several languages, Pope John Paul II took seriously the desires of the Second Vatican Council to revise the Code of Canon Law, which hadn’t been done since 1917, and to revise the Universal Catechism, which hadn’t been done since the Council of Trent in the 16th century. The 1983 Code of Canon Law and the 1992 Catechism of the Catholic Church stand along with his encyclicals as a lasting monument to his commitment to truth and justice.

A pope with a strong understanding of young people, Pope John Paul II held international World Youth Days. Despite his age and health, crowds of nearly 3 million attended the event in Rome in 2000, and 800,000 from 173 countries gathered in Toronto two years later.

When he died on April 2, 2005, Pope John Paul II had the third-longest reign as pope (26 years, 5 months, 17 days), behind only Pius IX (31 years) and Saint Peter himself (34+ years). John Paul II’s funeral was attended by 4 kings, 5 queens, 70 presidents and prime ministers, 14 leaders of other religions, 157 cardinals, 700 bishops, 3,000 priests, and 3 million deacons, religious sisters and brothers, and laity.

His successor, Pope Benedict XVI, beatified Pope St. John Paul II on May 1, 2011, the Feast of Divine Mercy Sunday. Pope Francis canonized him on April 27, 2014.

Discovering the stories behind beloved Catholic heroes

Discovering the stories behind beloved Catholic heroes Getting inspired by their faith

Getting inspired by their faith The Greek language, in which the Gospel was first written, uses the word Petros as the proper first name of a man and the word petra to refer to a rock. Peter means rock, but in Greek, as in most other languages except English, nouns have gender. Petra is the word for rock, and it’s feminine, so you wouldn’t call a man petra no matter how “strong as a rock” he may be. We believe that had Jesus used petra instead of petros for Peter, the other apostles and disciples would never have let Peter live it down because using a feminine ending would have been inappropriate. (These were sailors and fishermen, after all.)

The Greek language, in which the Gospel was first written, uses the word Petros as the proper first name of a man and the word petra to refer to a rock. Peter means rock, but in Greek, as in most other languages except English, nouns have gender. Petra is the word for rock, and it’s feminine, so you wouldn’t call a man petra no matter how “strong as a rock” he may be. We believe that had Jesus used petra instead of petros for Peter, the other apostles and disciples would never have let Peter live it down because using a feminine ending would have been inappropriate. (These were sailors and fishermen, after all.)