APPENDIX C

Accounting for Corporate Charges in Detail

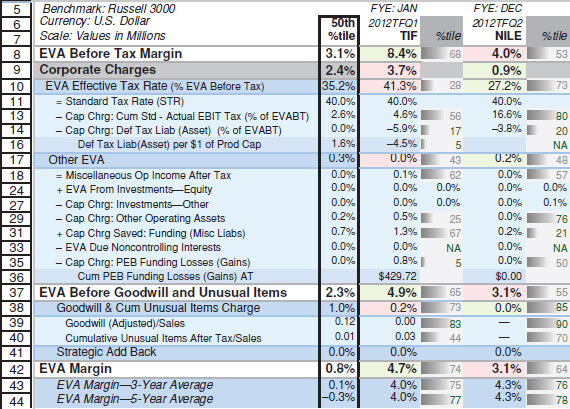

The report in Exhibit C.1 breaks out the detailed line items behind the corporate charges for Tiffany (TIF) and Blue Nile (NILE). It is not exhaustive of the items in this section, but it is usefully illustrative. Let’s walk through the corporate charges line by line.

Exhibit C.1 Tiffany’s and Blue Nile’s Corporate Charges in Detail

The biggest difference in the corporate charges between TIF and NILE is taxes, but it is not as straightforward as it appears. Not only does TIF have a higher tax rate, but the rate applies to a larger pretax EVA Margin. TIF’s 41.3 percent tax rate on its 8.4 percent pretax EVA Margin is equivalent to a charge of 3.5 percent of sales, whereas NILE’s 27.2 percent tax rate on its 4.0 percent pretax EVA Margin is a charge of just 1.1 percent of its sales. As this illustrates, companies cannot really be judged according to the size of their corporate charges because the charges might be bigger only because the pretax EVA profit margin is bigger. It’s the tax rate that reveals if the tax strategy has added value.

Why is TIF’s effective tax rate above the assumed standard tax rate of 40 percent? After all, TIF’s tax provision over the years has been consistently less than the assumed 40 percent rate, principally because of foreign source income. Remarkably, the normally hyperconservative accounting community is quite liberal in permitting companies to just ignore the extra U.S. tax that would be owed on repatriation of foreign income if management claims that the earnings will be permanently reinvested overseas. Under EVA, by contrast, the tax provision is computed as if all operating income, including foreign source income, was taxed at a standard U.S. tax rate of 40 percent, but since that tax was not actually paid, the accumulated deferred portion is credited with the cost of capital and applied as a reduction in the effective EVA tax rate. For Tiffany, the time value of postponing tax on foreign source income was 4.9 percent of pretax EVA in that year, as is reported on line 54.

More than offsetting that benefit, however, TIF carried a sizable deferred tax asset on its balance sheet. As is typical, payroll and other compensation have been accrued as an expense for book purposes but have not yet been paid or deducted on the tax books. A more significant reason is that TIF realized a $120 million gain on an asset sale/leaseback transaction. The gain was taxed up front but is being deferred for financial reporting. On net, TIF has already paid several hundred million dollars more in tax than its tax provisions have shown, and the cost of capital to finance that increased the company’s effective rate by 5.9 percent (line 55), bringing the overall effective tax rate to over 40 percent.

The second category, labeled “Other EVA,” is not a corporate charge but an offset to it. It is a net add-back to EVA coming from a sundry pool of items. The income and expense items are reported after tax. Moreover, if the items stem from capital charges or credits, they are computed using an after-tax cost of capital because at this stage the EVA elements are being measured after tax.

For Tiffany, the Other EVA grab bag is almost exactly zero, but only because of a coincidental confluence of debits and credits. It consists of the following:

Think this last one through. As noted, Tiffany has previously undertaken a sizable sale and leaseback transaction. Under EVA, the leased-back assets are treated as if they were owned and put back on the balance sheet. The estimated present value of the lease payments has been added to capital and included in PP&E in an amount that would presumably closely approximate the value of the asset at the time of the sale. Ironically, this means that the capital charge credit for the deferred gain coming through on the Other EVA line above is simply offsetting the added capital charge from including the stepped-up leased asset in PP&E capital. To a first approximation, the two cancel, and there is no net effect to EVA from swapping an owned asset into a leased asset. In reasonably efficient and competitive markets, owning and leasing are financing substitutes, except for taxes. And in this case, because the gain on the sale was taxed up front, the net effect of the transaction was to prepay taxes that would otherwise have been paid over the life of the asset. Bottom line: the cost of capital charge on the advanced tax payment makes Tiffany’s EVA lower than it otherwise would be as a result of the transaction. Ah, a thing of beauty—that EVA should penetrate the fiction and reveal the reality of even so gossamer a thread as that.

EVA BEFORE GOODWILL AND UNUSUAL ITEMS

A third corporate charge is still to come, but at this point we draw a line and record another intermediate EVA Margin. It is called EVA Before Goodwill and Unusual Items (line 78). It is what EVA would be if all acquisitions had been consummated without paying goodwill premiums and if there had been no one-time restructuring costs. It is a measure of what the go-forward EVA Margin might be on incremental business assuming those sunk costs are truly irrelevant and unlikely to recur. That is one possibility. You can be the judge. But the EVA Margin schedule says to have it both ways. Measure EVA both before and after the most abstract forms of capital, and derive whatever meaning you attach to each.

GOODWILL AND UNUSUAL ITEMS CHARGES

EVA is measured after all capital costs, including the after-tax capital charge on unimpaired goodwill and on the cumulative nonrecurring losses and charges, net of gains and credits, after tax. Those two charges come to naught for Blue Nile, and are 0.2 percent of sales for Tiffany,1 which is minuscule for a large company. Visa, BlackRock, Boston Scientific, Time Warner, and Symantec are among the firms that have accumulated so much goodwill and in some cases one-time restructuring investments that the charges in this category alone are over 10 percent of sales. Some of those firms have been very successful despite having such a large charge. BlackRock, for instance, has been able to successfully integrate and enhance the money management firms it has acquired where virtually all the purchase prices have been recorded as goodwill. Others, like Time Warner, were not so lucky. The merger with AOL turned out to be ill-timed, extremely pricey, and ill-conceived. The CEOs responsible did not last long.

The last line on the schedule prior to the EVA Margin is the so-called strategic investment add-back (line 82). That is where the cost of capital saved by holding out a portion of acquisition premiums or investment ramp-ups would appear. It is not automatically populated for public company data because we have not yet figured a sensible way to estimate it. But our individual clients use this account to accommodate major investments with delayed returns (as was described in Chapter 3, Accounting for Value).

1 Tiffany actually reports about $14 million of goodwill in its annual balance sheet, but the amount is so immaterial it is not broken out on the quarterly filings we are using; the goodwill is therefore included in the capital charge for other assets included in Other EVA.