CHAPTER 4

What’s Wrong with RONA?

RONA, ROI, ROE, IRR—take your pick.1 Each is a way to measure the productivity of capital, to relate profit to invested capital, or cash flow to spending, and to quantify the rate of return earned after getting the investors’ money back. Returns matter. Earning a return over the cost of capital is a prerequisite for earning EVA and adding value and enriching the owners. A CFO may also logically assume that a business line earning a higher return may be a better candidate than another for further investment and growth—assuming past results can be replicated. A higher projected return also provides assurance that a decision or plan is more secure, that a greater cushion exists to soften the blow should key assumptions prove untenable. And as an analytical tool, RONA can be traced to operating margins and asset turns in accord with the classic DuPont formula. It can be used to give line teams a rounded view of operating performance and balance-sheet asset management. For many reasons, return-type measures have earned a prominent role in financial management over the years, and are still very popular with CFOs the world over. But I come not to praise RONA. I come to bury it.

RONA and the other conventional return metrics are highly misleading and incomplete performance indicators, for reasons I will explain. And the deficiencies are far from academic. As you will see, companies that have aimed to increase RONA or maintain a high RONA have committed major blunders in strategy and resource allocation. And when RONA is judged from the bird’s-eye view of how well it performs as an element in a firm’s overall management system, it fails, or at least it is far inferior to EVA, as I have been saying and will continue to elaborate.

RONA fundamentally fails because it is inconsistent with what is—or should be—the main mission of every firm, which is to maximize the wealth of its owners. It is to maximize the difference between the capital that investors have put or left in the business and the present value of the cash flow that can be taken out of it. In short, the goal is to maximize MVA by maximizing the stream of EVA, as I have said.

Here’s the problem in a nutshell. RONA tells us about the ratio of market value to invested capital, but that is not the same thing as maximizing the spread between market value and invested capital, which is the true goal. A company that aims to maximize RONA will always tend to hold back and underinvest, underinnovate, underscale, and undergrow. It will leave value and growth on the table, and become vulnerable to a hostile takeover or a toppling by upstart rivals.

The glaring deficiency of RONA first became apparent to me in the early 1980s, when I had the privilege of advising the Coca-Cola Company. The beverage company at the time was fabulously profitable, earning nearly a 25 percent return on its capital, but also was a victim of its own success. Management was reluctant to put the Coke name on growth products like Cherry Coke, Diet Coke, and Caffeine-Free Coke because those products were reckoned to earn only a 20 percent return and would dilute the 25 percent return on the Coke brand. To complicate matters, the company needed to reverse a longstanding commitment. Coke’s founders had granted perpetual franchise licenses to promote growth of the bottling and distribution network, but by 1980 the independent bottling franchisees were parsed into economically undersized territories, in many cases run by lackadaisical third-generation owners. Coke needed to buy them up, consolidate contiguous regions, install hungry operators, and revise its pricing formula. But again, the capital to be invested in that strategy could not approach the phenomenal return from one of the world’s most valuable brands. So Coke was stuck because management was stuck on maintaining its high RONA.

The solution for Coke, as it is for every company, was to define success as growth in economic profit or EVA—even when that comes at the expense of RONA. RONA and EVA are cousins, not identical twins. RONA is the percentage ratio of operating profit to capital. It measures the productivity of capital. EVA is the dollar spread of operating profit net of the cost of capital. It is the total amount of value added over the cost of all resources. The distinction may appear subtle and effete. After all, EVA uses the same data as RONA—EVA measures profit less the cost of capital instead of profit divided by the capital. I’ve even had CFOs tell me they are using EVA when they are actually using RONA or return on capital. But in fact, the two are not the same at all. The differences are quite profound and incredibly far-reaching.

Let’s go back to the Coke conundrum. Coke’s weighted average cost of capital was about 10 percent at that time, and its RONA was running about 25 percent as I said, or 15 percent above the hurdle rate. Coke was thus earning an EVA profit of $150 for every $1,000 of invested capital. Suppose that to roll out the new products and acquire bottlers, Coke would double its invested capital while earning only a 20 percent return on the new money put into the business. Then its RONA would sink halfway between the two, from 25 percent to 22.5 percent, and its RONA spread over the cost of capital would narrow from 15 percent to 12.5 percent. But the percentage spread would be multiplied by twice the amount of capital, by $2,000. The EVA dollar spread would widen to $250, an increase of $100, and that is what counts. This is a classic example of where a decision sends RONA down while EVA and share price would go up.

By shifting to EVA and abandoning RONA, Coke decided in the early 1980s to expand its product portfolio and acquire its bottlers—which it might not have done had RONA remained the measure that mattered. The decision led the company to such a phenomenal improvement in its EVA profit that by 1994 Coke was producing the most MVA wealth of any American firm, as Fortune chronicled in a story titled “America’s Best and Worst Wealth Creators” featuring Coke CEO Roberto Goizueta on its cover as one of the best.

Other companies were not so lucky, Anheuser-Busch among them. For years the beer behemoth had opportunities to invest, acquire, and grow globally, but turned down all of them, leaving the firm ring-fenced and vulnerable to a hostile takeover. On November 18, 2008, the company reluctantly succumbed to the Brazilian-Belgian brewing company InBev. Anheuser-Busch became a target because its CEO, August Busch III, refused to dilute the RONA the firm was garnering in its U.S. beer business by entering more competitive overseas markets. As one adviser close to the company explained it:

When you have a business that was as profitable as his [August Busch III, CEO] was, where the returns were as strong as his were, I’m not sure anyone would be so smart to say, ‘We’ve got to take over the world,’” said one A-B adviser. “We understand now why he should have, but it would have diluted his margins and his returns.

—Dethroning the King, by Julie MacIntosh (John Wiley & Sons, 2010)

As an aside, InBev, the buyer, grew out of Brahma Beer, the first Brazilian company to adopt EVA. I helped Brahma to adopt EVA in 1996 after I got a call from the CEO, Marcel Telles, who became intrigued by it after Credit Suisse First Boston (CSFB) used EVA in an analyst report on Brahma. Telles was so curious he asked the CSFB analyst, “Where can I learn more about EVA?” which led to me. We spent about six months developing a program to measure EVA throughout the company, and it became a key asset and capability of the firm that helped it to successfully gobble up many other brewers and eventually become the world’s largest and most successful brewing company.

Coke and Anheuser-Busch are not isolated examples. You may know that the favorite business book of Apple’s Steve Jobs and Intel’s Andrew Grove is The Innovator’s Dilemma by Harvard professor Clayton Christensen. The book chronicles how established industry leaders almost always cede their top spots to upstarts that start small, in the low-margin end of the business, and then over time take over the whole thing. It persuaded Andrew Grove to coin the expression “Only the paranoid survive,” which is perhaps one solution. But Christensen thought a more fundamental reason better explained why top dogs are systematically reduced to also-rans and would lead him to prescribe a remedy other than paranoia to cure the Innovator’s Dilemma. His solution: managers must stop worshipping at the RONA church:

After puzzling over this mystery for a long time, he finally came up with the answer: it was owing to the way the managers had learned to measure success. Success was not measured in numbers of dollars but in ratios. Whether it was return on net assets, or gross margin percentage, or internal rate of return, all these measures had, in the past forty years, been enshrined in a near-religion (he liked to call it the Church of New Finance), by partners in hedge funds and venture-capital firms and finance professionals in business schools. People had come to think that the most important thing was not how much profit you made in absolute terms but what percentage profit you made on each dollar you put in. And that belief drove managers to shed high-volume but low-margin products from their balance sheets … this is why he called it a church—it was an encompassing orthodoxy that made it impossible for believers to see that it might be wrong.

“When Giants Fail—What Business Has Learned from Clayton Christensen,” by Larissa MacFarquhar, New Yorker, May 14, 2012

My favorite example of the Innovator’s Dilemma is IBM in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It’s still relevant because of the magnitude of the dilemma and for what the company’s CFO at the time said. Recall that IBM pioneered a major breakthrough with large mainframe computers in the 1960s after taking a big risk to develop the legendary IBM 360. An elite sales and marketing organization grew up to sell and service large corporate purchasers of the big boxes. When Apple and other West Coast upstarts first came out with diminutive desktop-sized computers in the mid-1970s, IBM dismissed them as mere toys, appealing to hobbyists, but certainly with no future as serious business machines. By the late 1970s, as the affordable personal computers were beginning to make serious inroads everywhere, the argument shifted. IBM’s CFO at the time, Dean Pfeifer, was quoted in BusinessWeek magazine as saying, “For us to invest in personal computers and dilute the 25 percent return we are now earning in the mainframe business would undermine the quality of our earnings, and we would not be acting in the best interests of our shareholders.”

What a gaffe. EVA says that as long as you have a better way to invest money than the market does, do it, and don’t worry about the impact on your company’s rate of return, or any other measure for that matter. But unlike Coke, IBM stuck to its ROI guns and delayed making an effort to enter the low end of the computer business until it was too late. Desperate to catch up, IBM belatedly formed a PC unit in 1980, relegated the team to offices in Florida, far from the corporate campus in Armonk, New York, and told them to develop a personal computer as fast as possible. And in their haste, they outsourced the software operating system to a tiny start-up called Microsoft. Holy mackerel. IBM gave away Microsoft. It is not an exaggeration to say that one of biggest mistakes in business history was due to a fixation on ROI.

I call this the Jose Reyes syndrome. Reyes was the New York Mets shortstop who won the National League batting title in 2011. And to ensure he did, in the last game of the season, he produced a drag bunt single, for him almost a sure thing, and then he just took himself out of the game to keep his average up. The best batter in baseball withdrew from the game to maintain a ratio? Hard to fathom, but that is essentially what IBM did, too.

A desire to drive returns can also lead to capital misallocations across internal lines of business. I discovered that when I met with Fred Butler, CEO of the Manitowoc Company, of Manitowoc, Wisconsin, in 1992. Fred had invited me to visit because the fund manager and occasional activist investor Mario Gabelli had taken a stake in the firm and was lobbying to break it up. The company consisted of three business lines—a Great Lakes ship repair business that was in the dumps, a crane manufacturing business that was also not doing well, and a crown jewel, the Manitowoc ice machine business, which held a large share of its market for hospitality ice machines and was earning about a 30 percent return on capital.

“How do you set goals, measure performance, pay bonuses?” I asked Fred. He replied, “It was previously based on growth in sales and earnings. But our managers spent capital so wantonly, we said we need to bring capital stewardship into the picture, and we switched to return on capital as our goal and compensation metric. But that has not worked, either.”

Fred continued, “The poor performers keep asking us for more capital to spend their way out of their hole and raise their returns, even with projects that are well under our overall cost of capital. And our best business, the ice machine business, is just treading water and is milking its return and forgoing growth. We are literally starving our stars and feeding our dogs. I did not think that was how it was supposed to work.” But that is how it works when RONA rules the roost.

I said, perhaps flippantly, “Well, then, it seems Gabelli has a good point about breaking up the firm.” Fred admitted, “Yes, he does, but I was hoping you had a better answer than just splitting up. How do we beat him and make him go away?” The answer, as you can guess, was EVA. The new success measure was to increase EVA. It saved the company. Faced with a charge for capital, the ship repair business was improved and sold, and the crane businesses shaped up and grew into a global powerhouse. Given the opportunity to win with any investment over the cost of capital, the ice machine business accelerated its growth and became the foundation for adding a whole range of food service products, including Garland and Frymaster, for example. The company’s stock soared along with its EVA, and Gabelli happily went away with a nice return. Nowadays, under the capable leadership of CEO Glen Tellock and CFO Carl Laurino, Manitowoc is in its 16th year of financial stewardship under the EVA banner. Manitowoc’s EVA is currently depressed, given the firm’s exposure to the construction cycles, but the company saw a turnaround coming a year ago, as the excerpt of its 2011 annual report shows (see Exhibit 4.1). I would bet on Manitowoc cooking up a terrific resurgence in EVA in coming years.

Exhibit 4.1 Manitowoc’s 2011 Annual Report Excerpt

The bottom line is this: EVA is additive, but RONA is not. Add something good to something great and EVA is greater still. Add a low-margin business to a strong one, and EVA increases so long as the cost of capital is covered. It’s value-additive. It is a measure to maximize, because more EVA is more net present value (NPV) and more owner wealth. But that’s just not true of RONA. There is literally no way to tell whether a company or division is better off reporting a higher or lower RONA, taken by itself. You can always try to jerry-rig RONA by combining it with other factors like growth, but all you are really doing is re-creating EVA by imperfect proxy. Why not make it simpler and more accurate and more effective, and just go for the real thing? Why not focus on a single measure that accurately scores the actual total value added by a business, by a plan, or by a decision—which is exactly what EVA does?

RONA is not only a misleading and incomplete measure at the corporate or line-of-business level, as I have discussed so far. It also fails to provide the correct answers concerning the configuration of individual investment projects or strategic choices, particularly when questions of how big, how fast, how many, and how much come into play. The reason is that the payoffs from investments and strategies typically increase and then decrease with scale. Rates of return initially grow larger and larger as more money is invested and unavoidable fixed costs are covered and market traction is gained. But at some point diseconomies set in. Costs inflate, distances widen, markets saturate, and the return begins to tail off as investment spending continues to ramp up. As a result, companies that focus on RONA will always tend to underscale their investments compared to what is optimal and leave profitable growth and added value on the table.

Consider the decision of how high to build a building as an example. Suppose a financial projection shows that a 10-story building won’t even cover the 10 percent cost of capital. The building is so small that the rental income cannot even cover the full fixed cost of the land. It’s a negative NPV project, and not worth considering except as a stepping-stone.

On the next step up the ladder, a 20-story building costs $20 million, let’s say, and it generates an 18 percent RONA and an NPV of $16 million. The return climbs because the additional rental income for the higher floors is gravy to cover the fixed costs. This is an example of increasing returns to scale.

But now it gets complicated. A 30-story building costs $40 million, or twice as much to construct. It’s more expensive per floor, and generates a RONA of only 15 percent. Extra elevator banks must be added, which cut into rentable space on all floors. The building requires sturdier reinforcement and takes significantly longer to construct, which delays the start of revenues. All these elements conspire to reduce the overall RONA of the proposed 30-story building to less than the rate of return projected on the 20-story building. This is an example of diseconomies of scale creeping in. Nevertheless, the 30-story building does show a higher NPV. Its NPV is estimated to be $20 million, or $4 million more than for the 20-story building.

The final candidate is a gleaming 40-story tower, costing a whopping $70 million to construct and generating a RONA just matching the 10 percent cost of capital, for an NPV of $0, as even more diseconomies of scale set in. It is, however, a magnificent structure and it will generate gushers of cash flow and EBITDA after the investment is made.

So what’s the correct decision—the 20-story edifice that maximizes RONA, the 30-story one that maximizes NPV, or the 40-story tower that maximizes revenue, profit, and EBITDA? If you cannot even agree on the correct objective, how can you ever make the right decisions as a management team? Is RONA, NPV, or EBITDA the real goal, since you cannot have them all?

True, the 20- and 30-story projects are both acceptable, being that both of them earn returns more than the cost of capital and generate positive NPVs. But the 30-story project is the best project, because it’s the one that maximizes NPV. It maximizes the spread between capital put in and the value gotten out. It maximizes corporate MVA, owner wealth, franchise value, and societal well-being by using scarce resources up to the point where incremental value added just exceeds the incremental resource cost.

There are two ways to see this. Compared to the 20-story project, the 30-story project costs another $20 million in investment, but generates an extra $4 million in net present value on top of that. The incremental project to build from 20 to 30 stories is attractive in its own right. Why reject that opportunity to add value just to maximize RONA? And the same reasoning applies to why management should not build a 40-story tower, for that is the same as taking on the 30-story building, a positive NPV endeavor, and then adding another project to build up to the 40th floor, which is incrementally a negative NPV proposition that should be rejected.

The 30-story project is also distinguished by its larger EVA. EVA can be measured by taking the percentage spread between RONA and the cost of capital, and multiplying it times the capital that is earning the spread. For instance, the annual EVA profit of the 20-story building is its 18 percent RONA, less the 10 percent cost of capital, times the $20 million investment. Its EVA is $1.6 million per year (and the present value of the EVA, at 10 percent, is $16 million, the project’s NPV, so it all checks out).

The EVA of the 30-story building is considerably higher, actually 25 percent higher. EVA is (15% − 10%) × $40 million, or $2 million. Capitalize the EVA at 10 percent, and you have the $20 million NPV, as stated. This is better. More NPV is better than less. True, the project will generate a lower overall rate of return, but the return is earned on more capital. Size matters, too. The right answer is always to choose more EVA, since that always translates into more NPV, which is why it is so important to use EVA not just to judge the performance of whole lines of business but also to use it for judging—and actually helping to improve—the value of individual projects.

But do not just take my word for it. The pitfalls of IRR and by extension RONA are well recognized in the finance literature. Scholars with no axes to grind join me in recommending that corporate managers stop using IRR and RONA. Consider this excerpt from world’s best-selling corporate finance textbook, Principles of Corporate Finance, by Stewart C. Myers (MIT Sloan), Richard A. Brealey (London Business School), and Franklin Allen (Wharton):

Many firms use internal rate of return (IRR) in preference to net present value. We think that is a pity. … Financial managers never see all the possible projects. Most projects are proposed by operating managers. A company that instructs nonfinancial managers to look first at project IRRs prompts a search for those projects with the highest IRRs rather than the highest NPVs. It also encourages managers to modify projects so their IRRs are higher. Where do you typically find the highest IRRs? In short lived projects requiring little up-front investment. Such projects may not add much value to the firm.

The bottom line is this: For decisions about how many SKUs to carry; how much advertising to do or research to perform; how big to build a warehouse, plant, or building; how many stores to open; and how much working capital to stock—in other words, whenever the dimensions of scale and growth must be weighed against margins and returns, or even a decision about how a product should be configured and priced or a production function fulfilled—then RONA- and IRR-minded managers are always apt to underscale, underinvest, and underinnovate compared to managers who are aiming to maximize EVA and NPV.

I was going over all this with Mike Archbold in the late spring of 2012. At the time he was serving as president and chief operating officer of Vitamin Shoppe, where he was instrumental in establishing a financial focus on EVA (Mike left in the summer of 2012 to become CEO of Talbots, and he was previously the CFO of AutoZone). “Bennett,” Mike said, “your building example resonates with me, but we call it the ‘S’ curve. We see it all the time: declining returns, followed by ramping returns, followed by cresting returns. When I was CFO at AutoZone, we got EVA so embedded as a financial discipline that even the marketing department got quite sophisticated at projecting the ‘S’ curve on marketing campaigns and we’d always look for the point to maximize the EVA profit.

“And here at Vitamin Shoppe, we’ve used an outside vendor to help us with automatic inventory restocking, which is actually a complicated problem, or at least we think so, because we look for the solution that maximizes our EVA, taking account of all the trade-offs. You’ve got to balance lead times, order size, inventory investment, warehouse and shipping costs, and the risk you are stocked-out and lose a sale and disappoint a customer, which means that cost is more than just the lost sales, but a bad customer experience. But we told our vendors, we want to put a price on everything and solve the program to maximize the expected net EVA profit, and it worked fabulously for us.

“The vendors, though, were quite surprised by our request, because their clients always ask them to figure out how to maximize the in-store stocking rate, to make sure they have the product on the shelves to never miss a sale. But that unidimensional focus is just as wrong as focusing on the return on capital or RONA. I mean, if RONA was the answer, it would really discourage us from ever making labor-saving capital investments. Why invest capital, even if it’s cheaper than the labor it replaces, when the capital goes into the denominator of the RONA computation and labor doesn’t? That’s nuts. And that’s how I can tell if a business operator is really business savvy. If they get EVA, they get value, and I can trust them to get the right decisions done. And if they don’t get EVA, what does that say?”

RONA can also be severely criticized for a number of mundane but very practical deficiencies. For example, RONA critically depends on how management decides to define the net assets in the denominator. Should excess cash or retirement assets or deferred tax accounts be included? How about off-balance-sheet leased assets? Should assets be measured net of impairment charges or at original value? Should assets be revalued or kept at historical costs? Should capital include all debt and equity or just equity? The answers to these questions can profoundly swing a RONA or ROI computation, and while EVA is not totally immune to these choices, it is far more resilient because capital is a cost, a deduction from the EVA profit, and does not enter into the denominator of a ratio. For instance, EVA is essentially the same whether leases are capitalized or expensed or whether capital is defined as debt plus equity or just equity alone. You can pay for capital either explicitly, by deducting rent expense or interest expense from the profit, or implicitly, as part of the weighted average capital charge deducted from EVA, and the resulting EVA is the same either way, whereas the RONA would be very different. And besides, the emphasis should always be on the change in EVA, and not EVA per se, which also makes the EVA goal even more immune to how the capital base is defined.

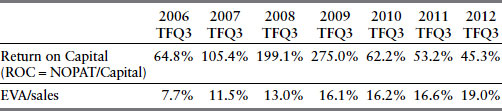

RONA is also highly distorted and essentially meaningless for new economy companies that tend to employ trivial amounts of capital. Over the past seven years, as shown in Exhibit 4.2, Apple’s return on capital, for instance, has been phenomenally high and extremely volatile, and basically useless as a performance indicator because its new economy capital base is so lean and variable. Apple’s EVA, by contrast, steadily increased from less than 8 percent of sales to 19 percent of sales as a clear indication of the increasing productivity and profitability of the firm’s business model.

Exhibit 4.2 Contrasting Apple’s Return on Capital and Its EVA/Sales Profit Margin

There are also some firms, and certainly lines of business, that operate with negative capital. Later on, we will see one—Blue Nile—a discount Internet retailer. The cash from its sales and trade funding is so prodigious it exceeds the firm’s meager investment in inventories and fixed assets. And with negative capital, its RONA is truly meaningless. Under EVA, though, negative capital simply counts as a profit rebate. EVA is credited with the value of investing the capital float at the firm’s cost of capital. As a result, Blue Nile’s EVA has been positive and generally increasing, and as a percentage of sales typically runs in the range of 3 percent to 4.5 percent, which puts Blue Nile’s business model around the 65th to 75th percentile in terms of how capable it is of driving EVA profit to the bottom line per dollar of sales. Again, this is just a foreshadowing of the EVA profit margin measure that will be introduced later on with more fanfare.

Another practical problem with RONA is that it is very tricky to apply to internal divisions that must be assigned assets. The knee-jerk reaction of line operators is to reject the allocation of assets to their business units in order to keep their RONAs up. But when the emphasis is instead placed on increasing EVA, managers shift gears and want to be assigned all the assets that they can legitimately manage. An initial assignment of assets reduces their division’s initial EVA, but that does not matter. What matters is whether they are able to better manage the assets they are assigned and improve their EVA going forward. EVA depoliticizes the management of the assets, and focuses on performance at the margin, ignoring irrelevant sunk costs. I have been in meetings where the operating teams literally changed their stripes on the spot, from vociferously rejecting the assignment of assets to their divisions to clamoring for more once they grasped the rules of the EVA game. RONA, by contrast, is inherently based on an accumulation of irrelevant sunk costs, and it encourages endless and fruitless arguing over the internal allocation of assets.

I must toss one last grenade in the RONA direction (I did come to bury it, after all). RONA is so inherently biased against integration and generally so in favor of outsourcing that it pushes activities outside the firm that should stay in.

To see how, let’s return to our simple sample company for another telling example. Recall that the company has $1,000 in capital and is earning $150 in NOPAT for a 15 percent return on capital, and with a 10 percent cost of capital, its EVA is running at $50. Suppose management considers moving $200 in computer assets from in-house management to the cloud for the exact same total of operating and capital costs, and without recording any gain or loss, so that the firm’s EVA remains the same, by definition. In the real world, outsourcing might pay or might not. The point of this exercise is simply to show that even if the decision to outsource is truly EVA and value neutral, RONA just won’t see it that way. It is an inherently biased measure that is unprepared for a world of business model diversity and complex choices. In this case RONA is going to go up because the firm has hived off a commodity investment that earns less than the corporate average return. Let’s work the numbers.

With the transfer of $200 in assets to the cloud, the company’s capital costs drop by $20 (by the 10 percent cost of capital), but since the transaction is a wash for EVA, by assumption, the incoming charges from the cloud vendor are going to raise the firm’s operating costs and reduce its NOPAT by $20. It’s a pure break-even exchange. There is no compelling reason to keep the computer systems or get rid of them by outsourcing. The outside cost and the inside cost, including the cost of capital, are identical.

Even so, the firm’s RONA increases from 15 percent to 16.25 percent. Although NOPAT falls from $150 to $130, the return is now calculated as a percentage of only $800 in capital. The outsourcing maneuver leads to a higher reported return on capital. That does not matter, though, because the higher return is earned on less capital. From a purely financial point of view, it must be value neutral— there’s no greater NPV, MVA, or stock price, since there is no more EVA. RONA was tricked into paying the decision a compliment it did not deserve.

It’s a contrived example, sure, but the insight is real. RONA is so biased in favor of outsourcing that it motivates firms to go bulimic, to become so lean and hollowed out that they eventually cut beyond the fat and into muscle, giving up essential long-run sources of competitive advantage, and really paying more for services they could perform more cheaply in-house, all costs included. EVA, by contrast, favors outsourcing only where a third-party partner has clear advantages that enable it to perform a function at a sufficiently lower total cost that it overcomes the disadvantages of having to contract and deal with an outside vendor.

I’ll give you an example of where EVA correctly motivated an outsourcing move. As I mentioned before, one of my EVA clients in the early 1990s was Equifax, the credit reporting bureau. It was then run by Jack Rogers, a former IBM senior officer. He was intimately familiar with IBM’s computer capabilities and thought that outsourcing Equifax’s extensive computer operations to IBM could make sense, if properly structured, even though the move would be quite countercultural. But to his credit, rather than mandating the decision or asking his team to simply trust his business judgment, which was, by the way, considerable, he said, “We have to run the EVA on it—it could be good, it could be bad, it’s EVA that will tell us.” As it happened, the facts and figures clearly showed an EVA advantage to turning over the company’s computers and operations to IBM, while Equifax retained its real franchise value in its hold on personal credit statistics and market presence. That was the very first large outsourcing transaction of its kind (which is why IBM for years used Equifax’s decision to showcase the merits of its outsourcing solution, based on the EVA analysis). As Equifax demonstrates, moving assets into the cloud or offshore for that matter can make sense—if it generates more EVA, but never because it increases RONA. An improved RONA is at best a by-product of making the right NPV/EVA decision, but should never be the prime motivator.

To say it one last time, only EVA always gives the right answer, to sourcing decisions or any other, because it’s the only measure that literally discounts to the net present value of discounted cash flow. There is no a priori reason to expect that RONA should give the right answer, and it frequently doesn’t; and there is every reason to think EVA will give the right, value-maximizing answer, and in my experience, it does, and it does so with more clarity, simplicity, and accountability than any other approach.

Why do so many CFOs persist in using rate-of-return metrics when they are so malevolent? I think there are two reasons. First, they’re ratios. They permit performance comparisons and investment rankings regardless of size. Their very defect is an advantage in giving CFOs a way to rate performance across divisions that differ in scale and to compare projects that vary in investment commitment. Ratio returns common-size the comparisons. Another reason is that a ratio replacement has not existed. For all its shortcomings, RONA or ROI was the best ratio kid on the block for ranking performance and investments. What was better?

Until recently, nothing. But now, a set of new ratio metrics developed by EVA Dimensions offers CFOs all the advantages of size-adjusted performance indicators without sacrificing the critical link to maximizing the money value of NPV, owner wealth, and overall corporate profit performance. The new ratios are, unsurprisingly, all based on EVA. The very good news is that the new EVA ratios can completely replace RONA and IRR and even operating margins and growth rates with a management framework that is fundamentally more accurate, simpler to use and understand, more informative, and considerably more effective as a practical framework for value-based corporate planning and decision making. Accept my premise, and there is no longer a reason to look at RONA, or ROI, ROE, or IRR, ever again.

1 RONA stands for return on net assets. In effect, it is the same thing as return on capital (ROC). Both are computed as net operating profit after tax (NOPAT) divided by net assets or net capital, which are equivalent. ROI is return on investment, and is just a generic term for RONA or ROC. ROE is return on equity. IRR is internal rate of return, and is based on determining the rate that will discount all cash flows to zero net present value (NPV). All the measures are in the same school of measuring the productivity of capital as a yield that can be compared against the cost of capital.