CHAPTER 5

The New EVA Ratio Metrics

Let’s face it. Ratios rule the business world. Managers, directors, and CFOs all need financial ratios to set goals and meter bonus pay; to measure, benchmark, and diagnose performance; to rate, probe, and improve business plans; and to judge risk, compare valuations, spot best practices, and isolate key trends, among other things. Most companies just use a jumble of standard, textbook financial ratios—growth rates, margins, returns, turnover rates, and so forth. I think we can do better—a lot better.

I think that finance ratios need to work in two directions. I describe the directions as E Pluribus Unum and E Unum Pluribus, from the many to the one, and from the one to the many. The solution I suggest is symbolically depicted in the American dollar bill. Apparently even the Founding Fathers were EVA advocates. It’s pictured as shown in Exhibit 5.1.

Exhibit 5.1 E Pluribus Unum and E Unum Pluribus

On the left hand, we need a measure of all measures, a summit score that correctly consolidates all the pluses and minuses of corporate performance into a single overarching financial indicator. That’s E Pluribus Unum, and it is writ in capitals across the banner above the eagle’s head. It stands for from the many to the one. From many peoples, from the many states, comes one nation. And in this case, we are looking to go from the many performance measures to the one score that really counts.

But as the pyramid on the dollar bill suggests, we also need to go the other way, from the one to the many, from Unum to Pluribus. We require an elegant means to deconstruct the all-seeing pinnacle score that stands at the apex and trace it step by step to foundational measures without ever losing sight of the big picture and while putting the individual measures in the context of all others. We don’t want to suboptimize; we want to maximize the whole. We need not just a score, but a management tool, an analytical framework, a way to dissect performance and help managers to discover ways to improve it.

We need the game score and we need the game statistics.

And this is where I confess that EVA totally failed in the past. EVA was traditionally just a money measure of economic profit, and managers were asked to increase it. The message was correct as far as it went, and a great help to many firms. But the method was incomplete. EVA needed a companion set of ratio statistics that fulfilled the many-to-one and one-to-many requirement, but it did not exist. If EVA was winning hearts and minds, and it was, it was winning with one hand tied behind its back.

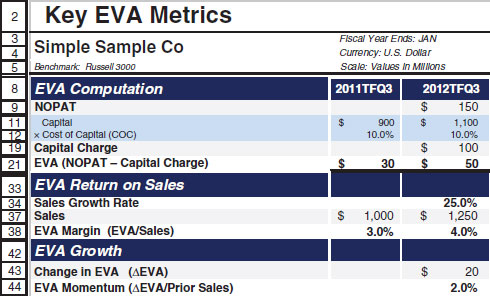

No longer. By adding a set of three interrelated ratio metrics to EVA, I believe we have reached the culmination of corporate value-based management. Together, the three key EVA metrics replace and subsume traditional ratio metrics with a superior and simpler framework. The table in Exhibit 5.2 highlights the three ratios I propose and the traditional metrics they displace.

Exhibit 5.2 The EVA Ratio Metrics Summary Table

Though they are billed as innovations, the new ratios are valuable not in making EVA more sophisticated and erudite or academically appealing. Their value is in making EVA fundamentally easier to understand and more effective as a decision support tool. It’s the Apple iPad version of EVA. The ratios are not the last steps you should get to in adopting EVA after you’ve done the EVA basics. The ratios should be part and parcel of how you roll out and use EVA from the get-go. You should use them, for example, in the early stages to introduce EVA to your management team and directors and showcase its applications and benefits.

When I recently reviewed the new EVA ratio framework with the former CFO of a major retail company, he said, “I always liked EVA but thought it was too hard to use and for our people to relate to their decisions. I didn’t think our operators would really get it, so I never brought it in. But the new EVA ratio program you’ve shown me really brings it to life. You’ve opened the curtain; you’ve really cracked the code.” Let’s see if you think he is right.

EVA MOMENTUM

The first new ratio, EVA Momentum, is the most important of them all. It is the change in EVA divided by prior-period sales. It is a way to measure the growth rate in EVA and make that into a ratable summary statistic. For example, say that a company had sales of $1,000 in 2010, and that its EVA increased from $30 to $50 from 2010 to 2011 (or from –$50 to –$30—it wouldn’t matter because only the change counts). Then its EVA Momentum for the 2011 year would be 2 percent. That’s the $20 increase in EVA over the $1,000 in prior-period sales. As I said, it measures the growth rate in EVA, scaled to sales. It can be measured quarter to quarter, year over year, over the past three to five years as a trend, and, even better, over the forecast life of a business plan. However measured, it is a simply magical metric in many ways.

First of all, and this is a real big deal, it is the only corporate ratio indicator where bigger is always better, because it gets bigger when EVA gets bigger, which means that a firm’s NPV and MVA and shareholder return are getting bigger, too. It is the one ratio measure that completely and correctly summarizes the total performance of a business in all ways that it can add value or subtract from it. Managers can legitimately aim to maximize EVA Momentum without fear of being misled into making dumb decisions. It can serve as every company’s most important financial goal and the overarching measure that matters. It is the Unum, the One. It’s the pinnacle score on the pyramid of measures.

To be specific, it can and it should be used instead of RONA, operating margin or sales, or EPS growth as the measure of performance and the arbiter of the quality and value of business plans. Put simply, a business plan is better and more valuable if it can credibly generate a greater EVA Momentum growth rate over the three- to five-year plan horizon. The greater the planned EVA Momentum, the greater is the projected growth in EVA, and the greater is the NPV of the plan and contribution it will make to the firm’s share price. CFOs are now using EVA Momentum to rank and grade the quality and value of their business plans and as a means to stimulate their line teams to plan for and deliver more EVA-capable and valuable business plans during the planning process. An entire chapter will be devoted to explaining just this aspect of EVA Momentum.

A second key attribute is that EVA Momentum focuses on change, on improvement, on turning points, on the news in the data, on performance at the margin. It is completely independent of inherited assets or legacy liabilities, and as such it is a more apt indicator of whether a business unit is a candidate for growth or contraction than RONA, because RONA incorporates the returns from all projects still on the books, no matter how distant, including by now highly irrelevant and outdated sunk costs.

By highlighting change, EVA Momentum also helps management to zero in on and magnify worrisome trends and to be more alert to emerging risks. Sales, net income, EPS, and certainly EBITDA can all continue to expand long after a business has really started to lose its economic vitality, but EVA Momentum turns down or at least slows down at the earliest stages of when a business is maturing or facing competitive pressures, or when its managers are overinvesting in incrementally undesirable growth opportunities. EVA Momentum brings all the pressure points into one score. It is like the proverbial canary in the coal mine, sniffing out trouble and raising a red flag before other measures get in the game, which gives management and directors more lead time to respond.

EVA Momentum also credits turnaround business divisions with adding value when they are able to make a negative EVA less negative. It gives managers overseeing troubled units the means to express the value they expect they can create by successfully reengineering their business model. It improves their ability to legitimately compete for funding on a par with other better-endowed divisions.

And on the other side of the track, EVA Momentum puts a Bunsen burner under the behinds of division managers in the most profitable business lines to keep innovating, investing, growing, and scaling to continue to increase their EVA rather than just coasting and milking the high returns and margins they already have. In short, EVA Momentum is the financial cure for the Innovator’s Dilemma. It most certainly supersedes RONA in correctly combining profitability and profitable growth at the margin into one overall score.

Bottom line: EVA Momentum is the ideal spanning measure, the one and only metric that CFOs can apply to diverse business units to fairly grade their performances and appropriately challenge them, regardless of the capital intensity of the business models or the current state of their profitability. Larger, multidivisional companies, populated with distinct lines of business and a spectrum of business models, will certainly benefit the most from having one EVA Momentum ratio metric to legitimately sit at the very top of all their performance scorecards and positioned as the key metric that matters.

Like all ratios, EVA Momentum is a statistic, but this one has real meaning. Any positive EVA Momentum is good, because that means EVA has increased; any negative EVA Momentum is bad, for then EVA has decreased, and zero EVA Momentum is a true breakeven. It is preservation of EVA without any expansion of it. It is zero EVA growth at the margin. And that, as it so happens, is pretty close to what the median firm in the market actually accomplishes.

Our analysis reveals that the long-run average EVA Momentum for the median Russell 3000 firm—the company swimming in the middle of the EVA performance pack—has been just 0.2 percent per year over the past 20 years. That’s all—just two-tenths of 1 percent. The typical firm just ekes out a slight rise in its EVA profit over time, once the full cost of capital is considered and accounting distortions are eradicated. In a world teeming with choices, change, and risk, it is apparently not easy to sustain gains in economic profit year after year. As economic theory predicts, the corrosive forces of competition, saturation, substitution, fading fads, bureaucratic creep, overpriced acquisitions, and management blunders tend to force returns back to the cost of capital over time and at the margin. This finding also legitimizes the default assumption used in EVA valuations: namely, that at some point almost all firms will find their EVA growth potential snuffed out and exhausted at the margin.

Not all firms are just treading EVA water, of course. Over almost any five-year interval about 40 percent of all firms increase EVA at a meaningful pace, and the better-managed or more fortunate firms increase it by quite a lot. Our research shows that the 75th percentile performer tends to run with an EVA Momentum growth pace between 1 percent and 1.5 percent per annum on average. That would be equivalent to generating cumulative EVA Momentum of 5 percent to 7.5 percent over a five-year stretch, meaning that a 75th percentile quality forward plan would have to produce a $50 million to $75 million increase in EVA for every $1 billion in sales. (One attraction of EVA Momentum statistics is that they can always be converted to a money target or benchmark for any one company or business division.) The 90th percentile EVA Momentum performance has been quite impressive, running at a 3 percent to 3.5 percent per year average rate over the course of rolling five-year spans. Then there are the truly rare and exceptional firms where EVA Momentum is inflating like an early stage of the universe. Just think Apple. Its EVA Momentum has been simply off the charts, averaging 22.8 percent per year over the past five years. It is a 19 sigma event, like having the four best men’s tennis players of all time playing at the same time. Enjoy it while it lasts.

Besides those general reference points, EVA Dimensions maintains a full range of EVA and EVA Momentum statistics for 9,000 global firms that breaks out into benchmarks by industry group, by company size, and by stage of the business cycle. Directors and managers now have the ability to quantitatively rank actual performance results and statistically grade the quality of plans through an EVA lens.1 We examine the statistics in depth in Chapter 7, Setting EVA Targets.

MARKET-IMPLIED EVA MOMENTUM

Stock prices can be reverse engineered to estimate the EVA growth rates that investors are implicitly projecting. It is a mathematical exercise to solve for the EVA stair-step increase that will discount back to the prevailing share price (technically, to FVA or future value added, the market-derived value of EVA growth), and then to divide that projected, expected EVA increment by the prevailing sales to compute a statistic called Market-Implied Momentum (MIM).2

For example, suppose the math shows that EVA must increase $10 million a year over 10 years, and then hold steady, to discount back to the current share price. If the firm’s sales are currently running at $1 billion, then its MIM rate is 1 percent. That’s the EVA Momentum growth forecast that is implicitly embedded in its stock price.

MIM turns out to be a far more reliable and useful statistic to quantify investor expectations than so-called consensus EPS, which (let’s face it) is not really a consensus, but an opinion survey of sell-side analysts that ignores buy-side investors who actually buy and sell stocks and set the prices, and as a flawed measure of short-term earnings, EPS hardly tells the whole value story. MIM, by contrast, literally discounts to the consensus stock price, and it gives a direct read for the expected growth in the firm’s EVA profit that is useful in three ways.

First, the higher MIM is, the more confidence investors are registering in the quality and value of management’s forward plan. CFOs and board members should monitor MIM over time to understand how well the company’s forward plan value and investor communications are being received in the market, and to be alert to any negative trends in investor expectations.

Second, MIM also provides a concrete bogey against which a firm’s actual EVA Momentum performance can be judged. A firm that is persistently underperforming the market’s expected EVA growth rate is asking for trouble. Tectonic pressure is building that will eventually convince investors to mark down the company’s stock price to reflect a more realistic expectation in line with the firm’s actual performance capabilities.

Third, CFOs can use MIM readings for their company and for publicly traded competitors to establish a minimum performance goal for their consolidated forward plan, a topic covered at length in Chapter 7 on setting targets.

EVA MARGIN

The third EVA ratio is a headline financial statistic in its own right, but it is also a cog in the EVA Momentum wheel. It can also fully replace the DuPont ROI formula with an analysis framework that is simpler to understand, more informative, and more inherently value-based.

It is called EVA Margin. It is the ratio of EVA to sales. It is the percentage of sales that falls to the EVA bottom line after deducting all operating and capital costs. Put simply, it is a firm’s true economic profit margin. It is a key summary measure of profitability and productivity, consolidating operating efficiency and asset management into a reliable and comparable net margin score. EVA Margin quite simply takes the mission of maximizing value and turns it into a sales-based, margin-based framework.

An alternative would be to divide EVA by capital, and develop a return on capital times capital-type analysis system. Although some might prefer it, I argue against it. I have already pointed out the many pitfalls of return on capital as a governing measure, and all those arguments speak against expressing EVA as a return on capital, too. But there are three more reasons why I believe a sales denominator is highly preferable to a capital denominator.

First, line managers don’t tend to think in terms of allocating capital and earning returns on it. To their way of thinking, those are the results of their plans and decisions rather than how they frame their decisions. Line teams tend to think much more naturally in terms of driving sales and improving the margin they earn on the sales. So my first objection is: let’s stop imposing a financial model of management on operating people.

A second reason to go with the sales and margin approach is that, with EVA, capital has already been accounted for as a cost, as a deduction from the EVA profit, so there is no need to divide EVA by capital. That would be redundant. What EVA says is: consider capital to be a cost, a charge to profit like any other, not a divisor. Make managers manage capital as a cost of doing business, as a deduction from their EVA and their EVA profit margin, rather than obscurely sticking it in the numerator of a ratio. Divide EVA by whatever factor is most appealing as a driver of EVA. My contention is that in most cases that would be sales (though of course other divisors may better suit, depending on the business model).

The third reason, and this is really the clincher, is that the EVA/sales ratio is a more reliable, transparent, and usable measure of business productivity than return on capital (or operating margin, for that matter). It is more neutral in more dimensions. It does not favor one type of business or business mix over another. It is less susceptible to accounting chicanery and distortions. It unfolds to reveal all of the business drivers more elegantly and recognizably. It is the door that leads from the Unum to the Pluribus. It is the pathway to walk the steps from the summit to the foundation of the EVA Momentum Pyramid. This will take some discussion and illustration to prove out. I will say a few words here, but the entire next chapter is devoted to singing the praises of EVA Margin, too.

I already discussed how RONA misleadingly increases whenever a firm outsources an activity that earns a return lower than the firm’s average return. Ironically, outsourcing also tends to misleadingly decrease operating margins. Move computers to the cloud, for example, and what was a balance sheet charge is now paid through cost of goods sold and selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expense. Traditional margin measures almost always take it on the chin when assets are outsourced, even when outsourcing makes sense. EVA Margin, though, gets this right because it folds the income and balance sheet effects into one score. It is fundamentally a better measure for determining how to draw the boundaries separating the corporation from its suppliers.

In a similar vein, EVA Margin neutralizes the capital difference among business models or between product lines and lets real performance productivity differences shine through. The capital charge is the great equalizer in this. Compare Intel and Wal-Mart, the one incredibly capital intensive with risky fabrication plants, the other incredibly lean with a rapid-turn, low-markup business model. The two cannot by any means be compared on any of their operating margins. But they can be compared on their EVA Margins, because, again, the capital charge is the great neutralizer. The key is that, in the end, and no matter what the business, all companies are really competing for EVA, so EVA Margin is the margin that matters.

Another thing that makes EVA Margin a better performance indicator is that it incorporates all the corrective accounting adjustments that make EVA a better measure of profit. We’ve covered these, so I will not enumerate them one by one. But consider just the fact that R&D and advertising spending are amortized over time with interest as a charge to the EVA Margin rather than being expensed. Tangible and intangible assets are put on the same footing in the EVA Margin model, as they should be. EVA Margins can thus be meaningfully compared between specialty chemical and commodity chemical companies, for instance. The specialty firms invest in R&D to generate higher gross margins, whereas the commodity-oriented firms invest heavily in efficient large-scale plant assets to drive their value added. It makes no difference to the EVA Margin. It treats the two the same and puts their different business models on a common performance rating scale.

Business models do not have to be as far apart as that to benefit from the consistency that EVA imparts. Try comparing Coke and Pepsi. You’d think a comparison of close peers wouldn’t find much difference. But in fact, Coke reports that a materially higher percentage of its sales is spent on advertising and promotion than Pepsi. In exchange, Coke reports a far higher gross margin. EVA Margin correctly levels the comparison. Or consider that close rivals Google and Apple differ in key ways that would trip up the conventional measures. Google is not only far more fixed-asset intense, with tons more money tied up in servers and systems than Apple has. Google also spends oodles more than Apple on R&D and on advertising and promotion—erroneously expensed with conventional operating margins and RONA, but correctly amortized with interest with EVA. A board member or business manager who consults the traditional financial ratios to compare the firms could easily be misled, but not so with the EVA Margin. The bottom line is this: A comparison even of close cousins is more incisive and reliable when the EVA accounting treatments substitute for conventional accounting rules.

I often meet CFOs who lament that they have no close public peers against which they can benchmark their firm. If they are thinking about benchmarking with conventional metrics, I agree with them. A better answer, though, is that they can always benchmark by comparing their firm’s overall EVA Margin performance (and EVA Momentum performance) against the statistics for the whole market. The whole market is relevant (and rough sector peers even more so) because, again, all companies are really in the same business of competing for EVA, and EVA Margin neutralizes differences in the business models, sourcing strategies, and accounting conventions, and provides a universally applicable scale to weigh performance.

Let me again cite the statistics for the Russell 3000 universe to give you a feel for the mile markers. Before I do, though, ask yourself this question: What do you think the typical running average EVA/sales margin ratio would be or should be for the median firm among the Russell 3000 companies? I usually get answers of 3 percent to 10 percent in my management presentations, but what do you think?

The average EVA Margin for the median Russell 3000 public company over the past 20 years has been—dramatic pause—just 0.4 percent! This is the major leagues, so producing a winning percentage over just break-even baseball is actually not bad. Product markets are quite competitive at the margin, way more than most managers appreciate. Most managers are accustomed to thinking in terms of EBIT or EBITDA margins, which give them a highly inflated impression of corporate profitability and how well they are doing. Those measures are unburdened by the cost of capital, uncharged for tax, and unsaddled with restructuring costs that EVA carries forward and considers to be part of capital. When the full economic costs of doing business are considered, the EVA Margins that surface are right on the razor’s edge and quite close to par, as again an economist would expect to be the case. But the implications are unsettling.

If EVA Margin is zero or close to it, as is true of the median firm, all the sales growth and book profit expansion in the world do no good for growing EVA. There is no Momentum without a Margin. By focusing attention on the EVA Margin, top management is better able to direct growth resources to where they truly can add value and not just spin wheels. Management is better able to impress line teams with how close the game score really is in most cases, and galvanize the teams to stretch for every advantage across the full income statement and balance sheet. Operating margins and EBITDA are corpulent and induce complacency where EVA Margins are lean and spark urgency.

As with EVA Momentum, the evidence shows the best firms are clearly able to run ahead of the pack. It is a right-tailed distribution. The 75th percentile firm has tended to earn an impressive EVA Margin of between 4 percent and 4.5 percent. Companies that are operating right at that upper quartile break point as of mid-2012 include firms as wide-ranging as Dell, Parker-Hannifin, Crocs, J.B. Hunt, Kellogg, Dollar Tree, and Starwood, to name a few. The 90th percentile performers operate at another great leap ahead, typically racking up EVA Margins of 9 percent to 10 percent. They include firms like Hershey, Becton Dickenson, Domino’s Pizza, Boston Beer, Nordson Corporation, AutoZone, and Idexx Labs. They again hail from all over the map. There are EVA winners and losers in almost every industry. Management and strategy and innovation and operational excellence and hustle can make a big difference. Industry is not destiny.

EVA Margins over 10 percent are rare and noteworthy, and that is where you will find Coca-Cola, Apple, Google, Coach, Visa, T. Rowe Price, Paychex, Microsoft, Dolby Labs, FactSet, and about 300 other true standouts among the Russell 3000 companies. Stepping down from those commanding heights, let me offer you the judgment that maintaining a bottom-line EVA Margin over 4 percent is darn good. In fact, I would venture to say that any company that sustains an EVA Margin that averages over 2 percent over a cycle is really not bad, not bad at all.3

Ask yourself these questions: How do the EVA Margins of your lines of business stack up against the broad market standards? Moreover, how do they stack up against your more relevant business peers? As important, what are the underlying drivers that account for the differences, and what priority should be attached to improving each? Later on, you will see how to take the EVA Margin engine apart and examine the moving parts that advance or retard the EVA needle. For now, though, let’s consider a simple example to get a feel for the full array of EVA ratio metrics I’ve introduced thus far.

A FIRST LOOK AT EVA MOMENTUM

We’ll do that by looking at the simple sample company once again, as is shown in the table in Exhibit 5.3.

Exhibit 5.3 Summary EVA Metrics for the Sample Company

Let’s start with the money measures, and then build into the new ratio metrics. Recall that SSCo generated an EVA of $50 in its most recent four-quarter year, the result of NOPAT of $150 and a 10 percent cost of capital applied to capital of $1,000—technically, that is the average capital outstanding over the year. As is shown on line 11, the opening capital balance was $900 and ending balance was $1,100 for an average of $1,000.4 Without showing the details, let’s assume SSCo’s EVA was $30 in the prior year, as shown on line 21.

These basic facts tell us two important things about the company right off the bat: it is profitable and it improved, as EVA increased from $30 to $50. But how significant a performance is that? Let’s size-adjust the money measures to find out.

Start with the EVA Margin. I have assumed that the company’s sales were $1,000 in the first year and $1,250 the next (line 37). Do the math. The EVA/sales profit margin was $30/$1,000 or 3 percent the first year and $50/$1,250 or 4 percent the next year (line 38). That’s an increase from about a 65th percentile EVA Margin to 75th based on typical Russell 3000 statistics. It is an impressive improvement in performance productivity, to be sure—and we’ll see where it comes from later—but that statistic understates the true extent of the firm’s overall performance in the year.

Total performance progress is measured by EVA Momentum, which is the $20 increase in EVA divided by the $1,000 sale base in the prior year. The firm’s EVA Momentum was 2 percent in the most recent year, as shown on line 44. That is comfortably above the 1 percent to 1.5 percent pace that typically marks the 75th percentile break point, but not up to the 3 percent to 3.5 percent demarcation line for the 90th percentile. It was quantitatively a very solid if not outstanding performance. The next question is: how did that happen? What performance factors were responsible? Eventually we will want to see them all. But let’s take this a step at a time.

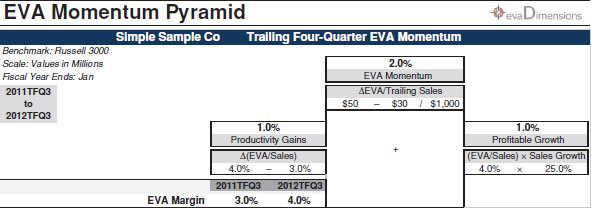

Inching down from the top of the Momentum Pyramid in Exhibit 5.4, the first step is to divide EVA Momentum into two main components, from which all other performance factors can be derived. The first is about running smarter, and the second is about running faster. The first one is called “Productivity Gains,” and it comes from generating an increase in the EVA Margin, and the second is called “Profitable Growth,” a multiplicative factor that comes from delivering positive sales growth at a positive EVA Margin (or from cutting back on sales that carry a negative EVA Margin). The EVA Pyramid chart lays out the two elements. It is the first step in going from Unum to Pluribus, from the one score to the many measures, with more details to follow. It shows that 1 percent of SSCo’s EVA Momentum came from getting better and the other 1 percent came from getting bigger. There was, coincidentally, an even split between the two. It was not only an impressive overall performance, but also a balanced performance. The car ran faster and it entered and won more races.

Exhibit 5.4 The EVA Momentum Pyramid

Let’s take a closer look at the productivity gains strut on the lower left side of the chart. It is the value added from increasing the EVA-to-sales ratio and from driving more EVA to the bottom line out of top-line sales. It is the value added from tuning up the business engine, expanding the EVA Margin, and enhancing the business model productivity through some combination of what I like to call the “3-P’s”—standing for price, product, and process. That says that EVA Margin expansion can come from earning and exerting price power, such as through leveraging brand, innovation, or service, or just getting prices right, or it can come from improving the product mix by putting an outstanding, all-star EVA-positive product lineup on the field (and benching products, and features, and customers that aren’t EVA positive), or it can come from process excellence, from running a tight, lean, efficient ship from top to bottom, through operations excellence and asset management, and even covering taxes, restructuring investments, acquisition pricing discipline, and integration success as key processes to manage.

Note, though, it does take an improvement in the EVA Margin to propel EVA Momentum. Just sustaining excellent processes or holding on to a wide gross margin would only maintain the current Margin and would not add Momentum, at least not in this category. It takes real productivity progress to increase EVA and to drive EVA Momentum, because EVA Momentum measures performance at the margin and is the news in the data.

The other main EVA Momentum category measures the value added from profitable sales growth. As for the sample company, it added 25 percent to its sales and earned a 4 percent EVA Margin, a combination that contributed the missing 1 percent to its EVA Momentum. That precisely quantifies how much value was added from delivering quality growth, and conveniently expresses it on the exact same scale as productivity gains so that visualizing the trade-offs is a lot easier.

In sum, the windswept and austere summit of the EVA Momentum Pyramid that we’ve just surveyed reveals just how well a company is performing and begins to unravel the performance story. As for SSCo, we can see at a glance that the firm generated a significant increase in its economic profit, and that half of the added value came from making the business engine run better, with more torque and spark, and the other half from making it run faster, a one-two punch that generated significantly more EVA heft, EVA growth, and EVA Momentum at the margin. You would be hard-pressed to reach those conclusions so quickly and reliably using other measures. Clearly, an advantage of this format is that it enables a manager or analyst to accurately summarize the value added and dependably rank the performance progress of what may be very different businesses or business plans. For example, it puts the value added from an improving turnaround story on precisely the same analysis footing as would apply to a growth star. It is an analysis method suitable for all business missions.

The Pyramid summit also naturally draws attention to the bird’s-eye conclusions as the first order of business and discourages managers from getting bogged down in the details before they can put them in perspective. It is always tempting to jump right into the weeds when reviewing performance, but the managers who do that not only are unable to see the forest, they can’t even see the trees. They literally get lost in the weeds. The approach I advocate is: Let’s take it a step at a time. Let’s first grasp the big-picture essence of how successful the business was in driving economic profit growth and then fill in the why and how pixels second. Let’s peel the onion in stages, but let’s start off knowing we are holding an onion and not a tomato.

Let’s consider a few alternative scenarios and see how easy it is to simulate EVA Momentum and how to drive it. Suppose that the sample firm’s EVA Margin had remained stuck at 3 percent. How much would pulling the carpet out from under EVA Margin expansion have hurt its EVA Momentum? Quite a bit. EVA Momentum would have been only 0.75 percent instead of 2 percent. In the absence of the productivity gains, EVA Momentum would come only from the sales growth, but now at only the 3 percent EVA Margin rate. This illustrates how really important EVA Margin is to EVA Momentum. Increasing the EVA Margin not only directly increases the EVA derived from existing sales; it also makes sales growth all the more profitable. It pays a double dividend, or its absence exacts a double penalty. Profitability trumps growth to a large degree in the EVA Momentum math.

Another insight is that all sales growth is not created equal. If a firm’s EVA Margin is zero or close to it, which is true of nearly half of all firms on the market, all the growth in the world adds nothing to EVA. Growth will propel sales, EBIT, EBITDA, and EPS, but will produce no EVA Momentum and therefore no added shareholder return at all (the shareholders will of course still earn the expected cost of capital return, but no more). Growth without a positive EVA Margin is the epitome of spinning wheels. Managers who start to see a low EVA Momentum score on their tally sheets will soon get the message—we’ve got to take better shots before we take more shots.

On the other side, even modest sales growth at a sizable EVA Margin can do more good than lots more growth at a lower EVA Margin. Consider Coca-Cola, a firm that is currently earning almost a 13 percent EVA Margin. Suppose its sales grow at a 7 percent a year clip (i.e., doubling in about 10 years, consistent with management’s espoused strategic goals). Without any change in its EVA Margin, Coke’s EVA Momentum would be 0.9 percent, close to the 75th percentile break point, and quite impressive for a firm that has been in business for over 100 years. Coke may not be a growth company judged by sales or EPS growth, but it is most definitely a growth stock judged by EVA Momentum.

What about a business with a far more modest but still quite respectable 2 percent EVA Margin that is delivering 30 percent sales growth? Its EVA Momentum rate is 0.6 percent. It is only two-thirds of the 0.9 percent Momentum pace that Coca-Cola generates with only 7 percent sales growth. This company’s sales and its EPS are expanding over four times faster than Coke’s. But growth in sales and EPS does not matter. Growth in EVA does, and on that score, Coke wins by a landslide. EVA Momentum trumps EPS momentum every time.

This illustrates how hard it is to correctly judge how various business units are really performing with conventional performance metrics. I could give you all of the data on metrics like operating margins, RONA, sales and profit growth rates, and such, and you’d be scratching your head for quite a while to figure out, if you could see the right answer at all, what you’d be able to see very quickly and far more accurately on the EVA Momentum scorecard.

What about a firm that is operating with a negative EVA Margin? Bear in mind that the firm could show positive net income and EPS along with EPS growth as long as it is covering the after-tax cost of the money it borrows. But if it is failing to cover the overall cost of capital and its EVA Margin is in the red, then the growth in all the other measures is only detracting from its EVA and subtracting from its value. The EVA Margin message to the managers is to wake up and stop throwing more good money after bad. Sales growth at a negative EVA Margin will only dig a deeper hole. The first commandment must be to improve the EVA Margin. Go on a diet before you enter the race. Get better before you get bigger. Repair the business model, restructure, and streamline; do what it takes to move to an incrementally positive EVA Margin business model.

Most CFOs would like to convey messages like these to their line teams, but the guidance is hard to explain with conventional measures. Combining EVA as a money measure with EVA Margin and EVA Momentum as ratio indicators is a much easier and more effective way to get everyone to see the light.

MARKET METRICS

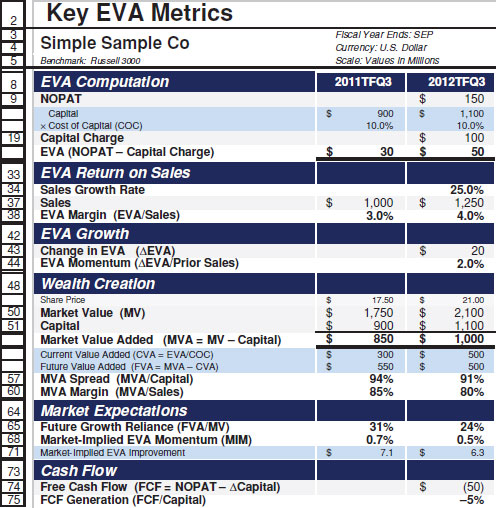

I beg your continued indulgence—we will very soon go into more depth on EVA Momentum drivers and apply them to Amazon. For now, though, I need to take you on a short detour to review the valuation metrics for our sample company and how they tie to EVA. After all, we do need to see how EVA ties to creating wealth.

Start with MVA. It’s the spread between the market’s valuation of the business, given its share price, and the capital invested in it (these appear on lines 50 and 51, respectively, in Exhibit 5.5). In Chapter 2 we valued the sample company under various scenarios for projecting and discounting its EVA. Now we are taking the opposite tack. We will use valuation statistics derived from hypothetical but realistic share prices to reach inferences about how investors perceive the sample company and view its prospects.

Exhibit 5.5 The Key EVA Metrics for the Sample Company

Two key findings are conveyed by the table in Exhibit 5.5. The sample firm’s MVA is positive and it increased over the year, from $850 to $1,000. The company has transformed valuable inputs into more valuable outputs, and it has enriched its owners. But more than that, the MVA expansion indicates that the firm is now adding even more value, is creating even more wealth, has enlarged its franchise value, and has beefed up the corporate NPV larder, compared to the prior year. To repeat, MVA, and the change in MVA, should be on the scorecard of every public company director. They are very telling measures.

Now let’s bring EVA and MVA together. As I’ve said, at any point in time, MVA should equal the present value of the EVA profit that a firm can be expected to earn in the future, which means that over time, changes in MVA should be best explained by changes in EVA. It’s no surprise, then, that the sample firm’s MVA was positive and increased when its EVA was positive and increased. Again, it is a made-up example, but the two are joined in principle and in practice.

Recall that MVA can be divided into two components—CVA and FVA. CVA, for current value added, comes from assuming that the firm’s EVA remains constant forever. In Chapter 2 we established that SSCo’s CVA is $500 (as shown on line 55). It is the $50 in EVA profit recorded in the most recent year divided by the 10 percent cost of capital. FVA, or future value added, is the portion of MVA attributable to the expected growth in EVA. Here it is determined by simple subtraction, as MVA minus CVA, to see what the market thinks it is. In this case it is $1,000 – $500, or $500, too, by sheer coincidence. It is shown on line 56. FVA is the prepayment the market is making in anticipation of strategic growth in EVA that hasn’t happened yet. It can be turned into two companion ratio statistics that quite usefully quantify investor expectations.

The first of those, as I discussed earlier, is Future Growth Reliance (FGR), or the ratio of FVA to market value. It is the proportion of the firm’s market value that depends on continued EVA Momentum. For the sample company, as shown on line 65, the reliance ratio ended the year at 24 percent. That says the firm’s market value would tumble 24 percent if investors became convinced that it would never be able to increase EVA above its current $50 level.

Reliance is a double-edged sword. On the one side, the higher the reliance percentage, the more confidence investors are registering in management’s ability to grow EVA. It’s the best defense against takeover and the most enticing invitation to raise capital for growth. An increase in reliance is also a key to increasing MVA and driving shareholder returns. The troubling bit is that when reliance is high, management actually needs to deliver significant EVA growth just to stay on target with investor expectations, and a slip, even a minor one, can precipitate a dramatic downturn in the firm’s valuation and owner wealth. It is obviously a very telling statistic that any CFO or board member should want to monitor and benchmark against other like companies and the market.

The second ratio that can be derived from FVA is even more important. It is the performance expectations ratio I introduced earlier in this chapter. It is Market-Implied Momentum (MIM). It is the average annual EVA Momentum growth rate that is implicitly baked into the stock price. Trust me on the math. The MIM rate impounded into the sample company’s latest market value is 0.5 percent, which is equivalent to an expected annual increase in EVA over 10 years of $6.25 (0.5% × $1,250 in sales in the last period), as are shown on lines 68 and 71 in the table. Put another way, the MIM rate projects that EVA will progress from $50 to $56.25, $62.50, to $68.75, and so on, going up $6.25 a year, for 10 years, and then it is assumed to go flat. The firm’s 0.5 percent MIM rate is above the 0.2 percent long-run average EVA Momentum delivered by the median firm in the Russell 3000 universe over the past 20 years. The market is apparently still expecting great things going forward for some time.

Future Growth Reliance and Market-Implied Momentum shrank over the most recent year. The reliance ratio ended up at 24 percent versus 31 percent the year before, and MIM dropped to 0.5 percent from 0.7 percent. Do those signal the market was losing confidence in SSCo’s future growth potential? Strictly speaking, yes, but that is chiefly because so much of the EVA growth that was expected as of the end of the prior year was actually achieved in the recent year, which left relatively less growth on the come.

MIM was 0.71 percent at the end of the prior year (shown on line 68), which translated into an expected annual EVA increase of $7.1 million (line 71) on the $1,000 sales base. The sample company ended up producing a lot more than that. Its EVA increased $20 million and EVA Momentum hit 2 percent. With almost three years’ worth of expected EVA growth coming in the one year, the EVA growth expected to come on top of that diminished somewhat, but still remained quite strong. Net net, what the company lost in expectations it more than made up with its actual performance. Put another way, the firm’s EVA increased 66 percent in the period (from $30 to $50) and its MIM decreased 30 percent (from 0.71 percent to 0.50 percent), but the combination still left shareholders with a much higher share price and far larger MVA in its wake.

Incidentally, the sample company is not at all unusual in this regard. It is common to see a bout of EVA Margin expansion and EVA Momentum growth countered by a cooling in MIM expectations. Investors generally expect competition and maturation to pull high EVA Margins and abnormally high growth rates back toward the universal market norm (and vice versa). We will investigate this phenomenon in greater detail in Chapter 7 on target setting.

There are two other valuation ratios I’d like to cover before moving on. These quantify the relative size of the firm’s MVA. The first one, shown on line 57 and labeled MVA Spread, is the ratio of MVA to capital. It is a wealth creation efficiency ratio. It is an improved version of the price-to-book ratio that avoids accounting distortions and leverage vagaries. In the most recent period it was 91 percent for SSCo, indicating every invested dollar had been transformed into 91 cents of added wealth, which is not bad by current standards. As of midsummer 2012, the MVA-to-capital ratio was 33 percent for the median Russell 3000 firm.

The second MVA indicator is MVA Margin, which (you guessed it) is the ratio of MVA to sales. It is the ratio of franchise value per dollar of revenue. It measures the efficiency with which the company is translating customer satisfaction into owner wealth. MVA Margin is 80 percent for the sample company in the latest period, also not bad; the mid-2012 market median ratio was half that, at 41 percent.

Although these are interesting statistics to quantify and benchmark wealth creation efficiency, be aware of their limitations. The table shows that the wealth indexes for the sample company decreased, but MVA increased and that is what really matters. As I have shown, it is the change in MVA that actually drives shareholder returns, and not changes in MVA ratios.

To complete the review, take a glance at the bottom section on the summary schedule. It shows a calculation of the company’s free cash flow (FCF) on line 74. The company earned $150 in NOPAT but invested $200 in capital as capital increased from $900 to $1,100 over the year, leaving free cash flow at minus $50. Divide that by the $1,000 in average capital, and the firm’s free cash flow generation rate, or net cash flow yield, shown on line 75, was –5 percent.

However expressed, the company invested beyond its internal cash sources, and was forced to tap external financing to fund growth. The cash flow indicators are bleeding red, and no doubt it was a hectic year for the firm’s treasurer. Yet it was truly a terrific year for the operating team and for the owners. EVA increased, EVA Margin increased, and EVA Momentum was upper quartile and way above prior expectations. MVA and owner wealth increased handsomely, too. The sample company joins Amazon as another classic example of why free cash flow after investment spending is such a poor and actually irrelevant measure of corporate performance.

Free cash flow can, though, be used in the formula to measure the total investor return (TIR), although again in a way I think is misleading. Recall that TIR can be computed as (FCF + ΔV)/V0. Plug in for SSCo:

It was a great year in terms of total investor return—over 17 percent. But the negative sign on FCF does not begin to explain why that is so. And now from the more helpful EVA point of view:

TIR = (Capital charge + EVA + ΔMVA)/V0

Plug in:

TIR = [$100 + $50 + ($1,000 – $850)]/$1,750 = 17.1%

The return is the same computed both ways, of course, but to reiterate the insight, cash flow and the cash-equivalent value change are merely the agents that transmit returns to investors. They are just the market’s messenger boys. Reversing the capital charge, earning EVA, and driving MVA and EVA expectations higher—all positive in this case—are the real backroom bosses driving and determining the returns that are parceled out to investors. Cash flow does not matter. Earning and increasing EVA does. EVA Margin and EVA Momentum tell us how well a business is doing in those return-driving departments.5

LET’S GET REAL—A FIRST LOOK AT AMAZON

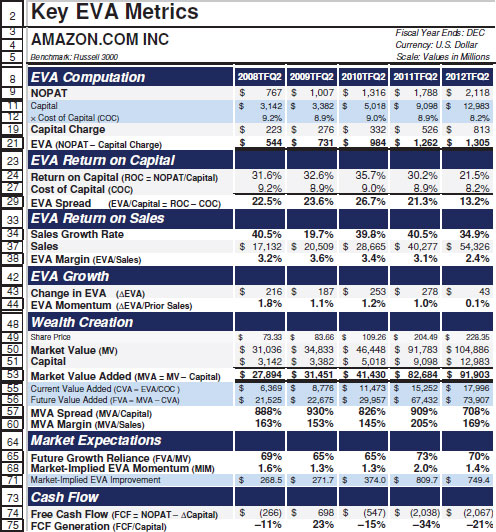

The table in Exhibit 5.6 presents the same key metrics table, but now for Amazon (AMZN), with one addition. There is now a section—starting on line 24—that reports the firm’s return on capital. It is the ratio of NOPAT to average capital, or the return on capital (ROC), which is my preferred version of RONA (not that I prefer RONA at all). It’s shown here to sound the drum I’ve already beaten, which is that RONA, ROI, or ROC (pick your poison) are lousy measures and you should stop using them. I’ll get to that.

Exhibit 5.6 EVA Metrics for Amazon

The table shows a five-year record, for years constructed from rolling four-quarter periods that conclude at the midpoint of 2012. The latest period shown, for example, is a composite of the last two quarters of 2011 plus the first two quarters of 2012, based on an analysis of 10-Q filings. Did I prepare this by hand? Heck no. I pushed a button and, presto, it appeared in a preconfigured Excel spreadsheet we call EVA Express. My team and I spent six years developing software that ingests reported financial data for 9,000 global public companies every night into a battery of servers, where a set of algorithms crunch the numbers according to our standard formulas for measuring the sacred EVA ratios. The next morning, while sipping my first cup of java, I can call up virtually any public company from all over the globe and see how it is faring on the EVA/MVA scorecard. The EVA data file also feeds a league-leading stock rating and ranking model we’ve developed, but more on that later.

Now, I’d like to ask a favor. It is your turn. Take a look at the vital statistics for AMZN. What do you observe, now that you’ve been schooled in the EVA ratio metric set? This is your big chance.

Okay, I never did my homework either, so here goes. AMZN has been amazing, in a nutshell. EVA is running at last polling at $1.3 billion, up from only $0.5 billion four years before, and it increased every year. EVA Momentum (line 44) has been strictly positive, a statistical rarity. Granted, the EVA Momentum pace has been slowing in recent years, and lately slipped well under the 1.4 percent or so MIM rate investors have baked into the firm’s share price (line 68). If you want to get concerned, Amazon is running a performance deficit. It is banking promises to step up the pace of its EVA Momentum and make its investments pay off in future years.

But that is looking ahead. As for the actuals, not surprisingly, MVA has been consistently positive and more than tripled over the four-year interval, from just under $30 billion at the start to over $90 billion at the end. That is more than $60 billion in added owner wealth, thank you. And, as expected, MVA has risen pretty much hand in hand with the EVA. To sum it up, AMZN looks remarkably like the simple sample company. Its performance has been truly impressive in all the ways that count, and at the same time, and like the hypothetical firm, there are contrary and misleading indicators to consider and discard.

As has already been noted, and as is shown in the table, Amazon’s FCF was negative—very negative in fact—and not just in the past two years. It was negative in four out of the five years, and cumulatively way negative. Investors have shoveled boatloads more cash into the firm than it has ever paid out. But none of that matters. Only growth in EVA and MVA matters.

But that is not all. After rising in the first two periods, AMZN’s return on capital (line 24) has melted down in the past two years. The most recent ROC is a good 10 percentage points lower than it tended to be over the prior four years. It is running at only about 20 percent instead of over 30 percent. And yet, although ROC is now at a low point, Amazon’s EVA, MVA, and share price are now at high points. Again, when ROC goes down and EVA goes up, it is EVA that wins the argument.

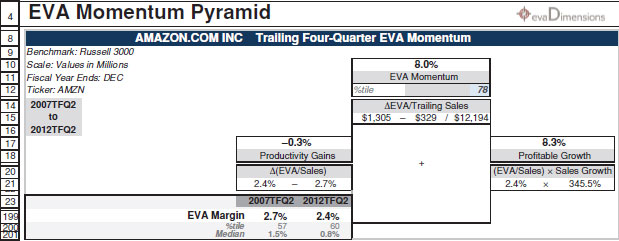

And what a case EVA makes. Amazon’s cumulative EVA Momentum over the past five years—computed from the cumulative change in EVA divided by sales five years back—was an even 8 percent, or a 1.6 percent per year average, as is shown on the Momentum Pyramid in Exhibit 5.7. How good was that? It’s 78th percentile versus the EVA Momentum accomplishments of all other Russell 3000 firms over that five-year span. The pace of EVA growth was really quite good, and yet productivity gains were a no-show in the performance, actually a slight hindrance, as EVA margin deteriorated by 30 basis points. The entire EVA Momentum—and more—was due to hyper sales growth—a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 34.7 percent and cumulative growth of 345 percent—at a slight but meaningfully positive EVA Margin.

Exhibit 5.7 The EVA Momentum Pyramid for Amazon

The most significant aspect of Amazon’s performance, which is the profitable growth element behind the $90 billion in wealth creation Amazon achieved, was totally off the RONA radar screen. And frankly, even the erosion in the EVA Margin, lamentable though it is, does not alter the basic conclusion, which is that AMZN produced a simply stunning performance and added value over the past five years. To put it in a tongue twister you can remember, the quantity of quality earnings matters more than the quality of the earnings. EVA Margin, too, is ultimately just a cog in the EVA Momentum wheel.

But what a cog it is. In the next chapter, I put EVA Margin under the microscope and show how it unfolds to reveal all the drivers of business model productivity in a step-by-step framework that is simple, informative, and practical as a management tool. It does the job so well it is my candidate to relieve from duty RONA and the DuPont ROI model.

1. Another interesting observation in the EVA Momentum data is convergence—a group of companies that earn upper-quartile EVA Momentum over a five-year interval are as a group likely to slow down and generate an EVA Momentum pace closer to the median over the next five years, which is why the market as a rule never assumes that a growth company will trade for the same multiple of earnings in five years that it does today, even though investment bankers’ acquisition pricing models almost always assume they will. The point is that it is even easier and more accurate to think of the terminal value in a discounted valuation in terms of how much EVA Momentum is likely to persist after the formal forecast period is concluded.

2. To be technical and to standardize the statistic, we solve for the annual increase in EVA that needs to prevail over a 10-year growth horizon in order to discount back to FVA—to the portion of MVA that is specifically due to the expected growth in EVA.

3. A more sophisticated approach would be to measure the average EVA Margin net of the standard deviation in the margin—what you might call the risk-adjusted EVA Margin—and look for that to be positive to know that the business was on the bright side of EVA.

4. In our software, average capital is measured even more precisely as the average of the average capital outstanding at the beginning and end of reporting quarters.

5. In fact, it is possible to explain TIR as a function of the EVA Margin, the EVA Momentum, the MIM rate and change in the MIM rate, and the sales growth rate. Again, it all comes down to the key EVA ratio statistics.