CHAPTER 9

Dividing Multiples into Good and Bad

It is one thing to develop a plan and forecast a value. It is another to ascertain how reasonable it is, and how it fits into the valuations of other companies on the market. When we developed the plans for Tiffany, we examined their reasonableness in light of the EVA performance metrics and the underlying drivers and assumptions, and the impact on the discounted valuation, which was all well and good. In fact, I think it is essential. But valuation multiples, properly understood, can also be used as reality checks on the reasonableness of corporate plans and forecasts. Valuation multiples also are a key element in the EVA stock-rating model covered in the upcoming chapter on EVA and the buy side. If nothing else, management should be prepared to respond to its board or to investors when asked to account for the firm’s valuation multiples compared to those of peers.

The most popular of the valuation ratios is, of course, the price-to-earnings (P/E) multiple. It also is the worst. P/E has a long legacy, back to a predigital age when computations of any kind were so hard to perform that simple metrics were preferred. That is not an excuse to keep using it now. I have already explained a number of times and in a number of ways that P/E multiples are horribly flawed and should be ignored. You will see further evidence of this in the next chapter when we look at acquisition valuations. I never look at P/E, and don’t see why you should. Let’s move on. There are better alternatives.

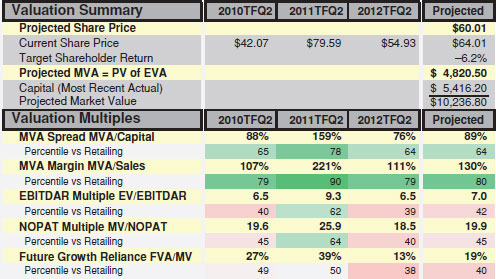

The sensible EVA-based valuation multiples are illustrated for Tiffany in Exhibit 9.1. The right-hand “Projected” column displays the multiples associated with the consensus forecast which, recall, discounted to a $60.01 share price, or just 4.5 percent off the actual price on the valuation date.

Exhibit 9.1 Tiffany’s EVA-Based Valuation Multiples

The first of these is MVA Spread, the ratio of MVA to capital. We’ve seen this before, but now let’s consider it more fully. It can be computed using the firm’s actual MVA, given its share price, and that is shown in the table for Tiffany as of midyear for each of the past three years. It can also be computed using the predicted MVA derived from discounting the forward-plan EVA as a way to judge the reasonableness of the plan. Tiffany’s predicted MVA under the consensus forecast was $4.82 billion, and its last reported capital was $5.42 billion. The MVA/capital ratio comes to 89 percent. This means that every $1 in capital in the business would translate into 89 cents of added owner wealth, according to the forecast. How high is that? It is hard to judge as an isolated statistic, but it is at the 64th percentile among the retailing crowd, as reported in the table. On that score, the multiple is on the high side, but not egregiously high. It is what would be expected for a company of Tiffany’s quality, and it is also in line with the percentile rank for the multiple in prior years.

A sister ratio—the MVA Margin, or the ratio of MVA to sales—is 130 percent under the consensus plan. Each $1 of current sales translates into $1.30 in franchise value. Tiffany’s MVA Margin ratio is pegged at the 80th percentile among retailing peers compared to the 64th percentile for the MVA Spread. Why the difference?

Tiffany, as we have seen, operates a business model that is far more capital intense than most retailers, which deflates the ratio of wealth creation per dollar of invested capital. Remember, though, that in the EVA model, capital is a cost, not a divisor. That’s why we tend to deemphasize the MVA/capital ratio in favor the MVA/sales ratio as a valuation metric, for that is the valuation multiple that ties directly to the sales-based EVA performance ratios. Without going into the gory details, a company’s MVA/sales ratio is always equal to its current EVA Margin and the present value of its projected EVA Momentum, divided by the cost of capital. It is the capitalized value of profitability and profitable growth. In this case, TIF’s 80th percentile MVA Margin ratio quite understandably corresponds with its 80th percentile EVA Margin and the 72nd percentile EVA Momentum projected in the consensus plan. If the EVA Margin and Momentum metrics are sensible and achievable, then the MVA Margin, and actually all other valuation multiples, must be as well. I will have more to say on this theme.

Another valuation ratio of note is an adjusted (read improved) enterprise valuation multiple. Traditional enterprise multiples are computed as enterprise value divided by EBITDA. This one is computed as the firm’s enterprise value, including the present value of rented assets, divided by the EBITDAR metric, which is measured prerent expense, as opposed to the conventional EBITDA figure, which is measured postrent expense. This is an even more totally unlevered valuation multiple than the EBITDA version. The classic enterprise multiple is distorted when the mix of leasing and owning assets varies, but this one sees through it (and thus it is the one used in the EVA stock-rating model, as will be discussed). TIF’s valuation according to the consensus plan is 7.0× trailing-four-quarter EBITDAR, which places this multiple at the 42nd percentile among the retail crowd. That’s a far lower rating than the MVA multiples, which clocked in at the 64nd to 80th percentiles. Why the discrepancy?

Here’s the answer. TIF’s EBITDAR is inflated—relative to those of other retailers—because TIF has relatively more of the expenses that are not deducted from EBITDAR but that the market truly considers to be important. Hence, its multiple of EBITDAR is lower. Like EBITDA, EBITDAR is measured before deducting depreciation, and TIF has gobs of depreciation of its asset base as compared to other retailers. EBITDAR is also before amortization of intangibles, and TIF has substantial amortization of advertising spending. Most significant, EBITDAR is before interest, including especially the full cost of capital charge that EVA takes into account and that applies to its considerable base of owned and rented assets and also to its immense investment in working capital and in brand equity. And TIF has a particularly high EVA tax rate from its hefty deferred tax asset account. In all those ways, EBITDAR substantially overstates the EVA profit the market is really valuing to a more extreme extent than it does for other retailers, so that the valuation multiple of EBITDAR is understandably lower than its MVA ratios relative to its peers. EBITDAR or its bastard cousin EBITDA are both truly earnings before many things that count, and that the market obviously factors into valuations. Again, if, the EVA performance metrics are reasonable, then the valuation is reasonable. Do not start to doubt the valuation because the multiple seems out of line. Figure it out. There is almost always a sensible way to explain why the multiple diverges.

The next multiple down the list is a step in the right direction. It is the ratio of market value to net operating profit after taxes (NOPAT). It is 19.9× for TIF’s consensus plan, or 45th percentile. Besides cleaning up sundry accounting distortions, NOPAT differs from EBITDAR in that it is measured after taxes (at the smoothed tax rate and considering the benefit of deferring tax payments), and it is measured after setting aside the depreciation and amortization of wasting assets that must be replenished or replaced to keep the profits flowing.

As a result, NOPAT comes a lot closer to the distributable cash flow that the market really values. This is because NOPAT measures the net cash flow the firm generates after setting aside a necessary allowance to recover and maintain the capital, as opposed to EBITDA or EBITDAR, which are gross cash flows, and thus inherently unsustainable. Granted, the reported depreciation and amortization costs are not perfect measures of the true replenishment costs. But the reported charges are almost always a more accurate indication of the real cost than to assume the charges are null, which is what EBITDA and EBITDAR do. Our research shows conclusively that NOPAT multiples better explain and predict stock prices than the cash flow multiples do.

To be specific, recall that NOPAT is in principle the free cash flow that would be available as an annual liquidating distribution assuming there is only investment to maintain the status quo and no investment for growth. Under those assumptions, a firm’s intrinsic market value would be just its normalized NOPAT profit divided by the cost of capital. It is its NOPAT capitalized as a level perpetuity. For Tiffany, given its 6.3 percent cost of capital, the basic NOPAT enterprise multiple should thus be 15.9× (1/6.3 percent), just the inversion of the cost of capital.

Tiffany’s actual NOPAT multiple is 19.6×, or 4× NOPAT higher, because the firm’s market value goes further than just capitalizing NOPAT and also includes the present value of the forecasted growth in EVA. Put another way, 4× of the 19.6× multiple, or about 20 percent of it, is implicitly due to the value of the projected growth in EVA. All this helps us to understand the NOPAT multiple better, and why it is better than any of the cash flow multiples. And yet, for all that, the NOPAT multiple is not an especially efficient way to home in on the key valuation question, which is: how much of the company’s market value depends on, and is at the risk of, EVA growth? Granted, the answer to the question is contained in the NOPAT multiple, but it is hard to isolate it, which brings us to the next and final multiple of interest.

The culminating EVA ratio shown in Exhibit 9.1 is Future Growth Reliance (FGR)—the percentage of the market value attributable to the growth in EVA, and a sister to the Market-Implied Momentum statistic. In this case, it is the percentage of the forecast market value that is attributable to the consensus forecast for growth in EVA. Tiffany’s projected EVA growth reliance is 19 percent, which is only the 40th percentile among peers. It is another indication that the plan is not exceptionally aggressive, at least as far as the proportion of the value that is contained in the projected EVA Momentum. That’s nice to know, but then, how does that conclusion square against the much higher MVA multiples we’ve seen? And how does it square against the 0.9 percent EVA Momentum that was forecast in the consensus plan, which was rated at the 72nd percentile compared to the Momentum accomplishments of its peer group? It seems too low, perhaps?

It is not. Remember, the value used to compute all the multiples is the same—it is derived from discounting the consensus EVA plan. So if any one multiple appears out of line, then you just need to figure the reason for the discrepancy rather than questioning the valuation.

Here’s the explanation. Recall that MVA comes from the present value of current EVA plus the present value of projected growth in EVA. The preponderance of Tiffany’s MVA is in the first bucket. It is so profitable right out of the starting gate, with an 80th percentile EVA Margin, that the lion’s share of its MVA is derived from its embedded EVA and not as much, relatively speaking, comes from the EVA growth component. TIF illustrates the rule that where MVA is high and FGR is relatively low, you have a company that is already quite profitable and whose projected EVA growth is simply less important by comparison, no matter how good it may be on its own terms. It is the perfect portrait of an established aristocrat—an apt description of Tiffany, eh?

This illustrates an important rule. You can read the MVA/sales and FGR ratios in tandem to get a full stereoscopic view of a company’s valuation, and dispense with all the others. Suppose you performed a valuation of a forward plan and found it translated into a relatively low MVA/sales ratio but a relatively high FGR ratio. What would that indicate? That the company’s EVA is currently underwater; it is expected to improve significantly, but will nevertheless stop short of ever reaching high ground. It is a firm deep in the valley that is expected to climb to a base station and no higher.

What if both ratios are high? That’s really terrific. The valuation multiples are telling us the company is currently an EVA Margin star and is a prospective big-time EVA Momentum winner. It is a great company that is forecast to become greater still. It’s like a phenomenally talented midcareer athlete with years of outstanding performances still to come. It’s Roger Federer after winning the 2006 U.S Open, his ninth of 17 slams, and counting. Again, the two ratios taken together give you an efficient and reliable way to understand and benchmark the valuation story. There really is no need for P/E or an enterprise multiple in any form. They are at best redundant, and almost always inferior.

So concludes our short detour into the world of valuation multiples. A personal goal for this conversation was to demonstrate just how slippery and opaque multiples can be. There’s a lot going on inside the ratios, and if you look closely at the conventional ones, they are so flawed that it is really hard to gain any reliable insights from them. I fear that CFOs and CEOs and investor relations (IR) directors spend a lot of time going in circles on those, and it is largely fruitless. If you are to look at any, I urge you to consult the EVA valuation multiples I have explained. They are more efficient, and they are more dependable.

I will go further, though. I am suggesting that less reliance be placed on valuation multiples in general. Up to now, valuation multiples have been the best available means to judge the overall quality of a plan or the degree of stretch in it. But now it is possible to judge the forecasts directly. The projected EVA Momentum and EVA Margin statistics that characterize the plans can be benchmarked against the profiles of actual corporate accomplishments, against market-implied rates, and in the context of the EVA Momentum math. Do not abandon multiples. MVA/sales and FGR have a role to play. But you are now able to shift the emphasis toward a quantification of the EVA performance metrics that so succinctly, completely, and accurately characterize the financial and valuation essence of the plans.