Even while British forces had been bottled up at Boston, key figures had been considering New York as a more suitable starting point for an offensive campaign in 1776. The position of the colony, dividing New England from the south, made it strategically important. New England was seen as the driving force behind the revolution, while the southern states provided the supplies needed to maintain resistance against the British. This no doubt oversimplified matters, but the convenient location of the Hudson River, neatly dividing the colonies in two, made it seem possible to cut off the militant New Englanders from their supply base.

In fact, so seductive was this strategy that no other appears to have been seriously proposed, save for that of the Secretary at War, Viscount Barrington, who favored a naval blockade and only limited land-based operations. The Hudson strategy also had the benefit of allowing Britain to concentrate on one area with the hope of attaining complete success. Anyone with a grasp of military reality would know that actually conquering all 13 colonies was an impossibility with the limited resources at hand. The apparent possibility of forcing the colonists to give up their struggle by such a simple method as controlling a river must have been irresistible.

New York had originally been New Amsterdam. A British army under the Duke of York, younger brother of Charles II, had taken it in a bloodless campaign that in many ways was startlingly similar to that of 1776—a landing at Gravesend Bay took place on August 26, 1664, while British troops occupied what was now “New York” on September 8. (LOC, LC-USZ62-46068)

Howe’s army would be the main force in the strategy. Having established a base at New York he would move up the Hudson to link up with a smaller army under Carleton moving down it. Having secured the length of the Hudson the British could then launch expeditions against New England. The only major obstacle, it appeared, was Washington’s Main Army. With a large enemy army in the field the British would never be able to maintain control of the Hudson—isolated garrisons would be easily overwhelmed by a sizable force and the aim of cutting off New England from the other colonies would be unattainable. For the strategy to succeed, the Main Army needed to be crippled or, better yet, destroyed entirely.

Previously known as Lord George Sackville, Germain had been court-martialed for his slowness to respond to an order at the battle of Minden and had been declared “unfit to serve his majesty in any military capacity whatever.” (LOC, LC-USZ62-45273)

The replacement of Dartmouth with Germain as Colonial Secretary was a factor in the decision to wage an aggressive campaign against the Americans. Germain shared the opinion of many that “one decisive blow on land is absolutely necessary.” He also believed it might be all that was necessary, a comforting notion considering his doubts about the possibility of actually conquering the entire country. “As there is not common sense in protracting a war of this sort,” he commented, “I should be for exerting the utmost force of this kingdom to finish the rebellion in one campaign.”

“Yankee Doodle 1776”—an effective depiction by Archibald M. Willard of the often disheveled but stubborn men of all ages who fought in the war for independence. (LOC, LC-USZC4-694)

The king had no control over the finer details of military operations in America, but he was hawkish in the extreme and felt the colonists needed to be taught a sharp lesson by Howe’s army. (LOC, LC-USZ62-7819)

This view of New York, emphasizing as it does the waterways enveloping the city, is a good indication of why the British felt it would make a fine starting point to restoring order in the colonies. (LOC, LC-USZ62-46050)

Perversely, the difficulties with which Howe had extricated his army from Boston now worked in his favor. Unable to move directly to New York because of the disorganization of his evacuation of Boston, the loss of supplies and the limited number of transports, he had been forced to go to Halifax, giving Washington the chance to make perhaps his most serious mistake of the war—the decision to defend New York.

British military preparations were given an added twist by the fact that the Howe brothers were also authorized to act as peace commissioners. This would put them in the awkward position of attacking rebel forces in the field at the same time as attempting reconciliation and the duties would probably have been better undertaken by separate parties. The affection the Howes both felt for the colonists is also an important factor to consider. Would William Howe be willing to destroy Washington’s army if he got the chance? His performance around New York would make that a very interesting question indeed.

Washington’s army, as it stood in 1776, was not capable of defending New York, but there was immense political pressure not simply to give the city up. Certainly the uncontested loss of a major city would have been a severe blow to the morale of the soldiers under Washington. Conceding the inability to oppose the British military juggernaut was not the way to start a campaign.

Washington decided to stand, therefore, and was immediately faced with the near impossibility of the situation. British naval supremacy meant that a good deal of the defensive effort had to be expended on limiting the range of the Royal Navy’s warships. Situated on the tip of Manhattan (or York) Island, the city could be bypassed by ships on both the North (Hudson) and East rivers. To cut off the Hudson, Fort Washington was constructed midway along Manhattan on the commanding heights of Mount Washington and further batteries were placed on Paulus Hook in New Jersey.

Emplacements in New York City itself protected the East River, but these themselves were vulnerable to any guns placed on the Brooklyn Heights on Long Island. Washington was forced to build fortifications there as well to prevent the British from simply occupying the high ground and compelling the evacuation of New York. The Main Army, with no naval support, would therefore be split over two islands in the face of a major maritime power and a superior army.

Work at Brooklyn commenced in February 1776, under plans drawn up by Charles Lee, but Lee himself had ventured the opinion that New York could not be held. He hoped merely to turn it into “an advantageous field of battle.” When Lee was sent south to Charleston Brigadier-General William Alexander, who claimed the title of Lord Stirling, took up the work. Lee’s plans for three redoubts and entrenchments to protect the Brooklyn Heights from attack from the East River were changed and a single fort was constructed instead, Fort Stirling. Interestingly, no efforts had yet been made to protect these works from an attack from the interior of Long Island. It was not until July that Colonel Rufus Putnam initiated works to remedy this situation. A string of forts and redoubts was stretched across the Brooklyn Peninsula, anchored at both sides by marshland and inviting a costly frontal assault. Two more forts (Defiance and Cobble Hill) completed the rebel defenses at Brooklyn.

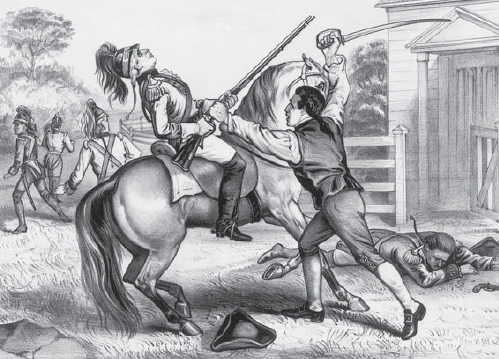

A rather fanciful depiction of a “Patriot of 1776 defending his homestead.” The patriot in question has laid one dragoon low and is setting about another. (LOC, LC-USZ62-20453)

Washington based his strategy on the hope that the British would be unimaginative in their assault. He had constructed defensive works at Brooklyn and throughout Manhattan, hoping to exact heavy losses at each point. A ridge of high ground running across Long Island, the Gowanus Heights, was later adopted as a forward defensive line. Initially only an extra zone of resistance, Washington came to view this as the best chance of stopping the British. The slope was gentle on the defending side, steep and heavily wooded on the other, and it was easily passable only at a small number of places. Troops were placed at each pass behind felled trees and it was hoped that the British would get no farther.

Under the direction of Israel Putnam the Americans also seized and fortified Governors Island and hulks were sunk between it and the battery at the tip of Manhattan to further impede British shipping. It is impossible not to wonder why further defensive works were not constructed to guard the narrow stretch of water between Staten Island and Long Island, but the fact is that the Americans had limited resources and manpower. They had done what they could but Washington, quite rightly, had a sense of foreboding. “We expect a very bloody summer …” he wrote his brother on May 31, “and I am sorry to say that we are not, either in men or arms, prepared for it.”