1939-1942

Richard Feynman received his undergraduate degree from MIT in June of 1939. He then went on to Princeton University for his graduate studies (when he expressed interest in staying at MIT, Professor Slater advised him not to: “You should find out how the rest of the world is”). In these early letters, he wrote to his parents in Far Rockaway, Queens, of his first forays into teaching and the vagaries of student life: canned food, lack of funds, and irregular hours.

In addition to his devotion to physics and, later, the war effort, a young woman by the name of Arline Greenbaum was another major involvement during this time. Arline and Richard married on June 29, 1942, just two weeks after he had received his Ph.D.

Aside from the youthful voice reverberating in these early letters, several of them display themes that would echo throughout Feynman’s life.They reveal a great eye for the telling detail, confidence in his decisions, and a curious ambivalence toward time. Although he was careful to note the time of his writing or the time he went to bed the night before, for example, he often noted the date as “I don’t know what” or simply omitted it altogether.

Feynman was just starting his professional climb, and his letters from this period are infused with energy and enthusiasm. His first published paper dates back to this time, and incidentally, it came in the form of a letter to the Physical Review. Co-written with MIT Professor Manuel S. Vallarta, the paper explored stars’ interference in the scattering of cosmic rays. Although it was not itself groundbreaking, it contained the thought processes that would come to characterize his work and foreshadowed his great papers of the late 1940s.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO LUCILLE FEYNMAN, OCTOBER 11, 1939

Richard was twenty-one years old and had just begun his studies at Princeton in New Jersey, seventy miles from his family in New York.

Tues. Oct—1939

Dear Mom,

I like your idea about coming to visit me alone some time very much. Why don’t you just jump on a train some Sunday morning and I’ll meet you at the station.You don’t need Pop—you’ll only have to worry about whether he can get anything to eat in the restaurant, etc. Not that I don’t want to see Pop—but he’ll drop by alone lots on business trips—so you make a little inexpensive outing just for yourself—any Sunday you say, provided I know which one so I can meet you. In fact, if you are worried about the expense let me treat you. It will be fun.

The raincoat came O.K. It is very nice. I think they make raincoats very stupidly these days—the bottoms of your pants get all wet. Now that I have the raincoat it is hot as hell (excuse the language but hell is damn hot, so is “it” and the sun is shining brightly).

Prof. Wheeler was called away suddenly last night so I took over his course in mechanics for the day. I spent all last night preparing. It went very nicely and smoothly. It was a good experience—I guess someday I’ll do a lot of that.

Things are rather uneventful. I didn’t fall in the water while sculling these last two times, so maybe I won’t fall in anymore—so saying he fell in.

I’ll tell you all about things when I get home.

Love,

RP Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO LUCILLE FEYNMAN, NOVEMBER 1939

Monday Nov. I don’t know what

Dear Mom,

The best news to really write home about is, unfortunately, already known to you. Arline came to visit me.We had lousy weather but a good time.

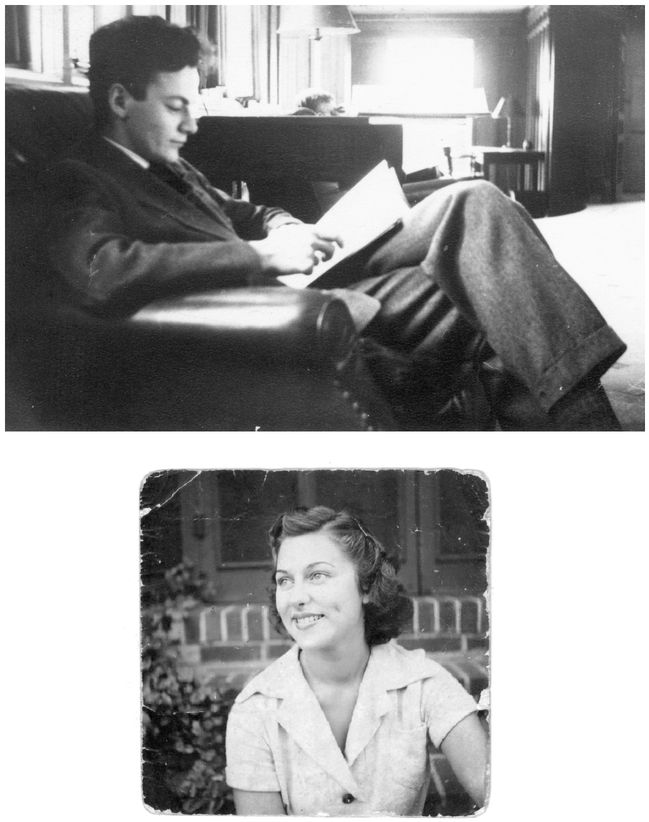

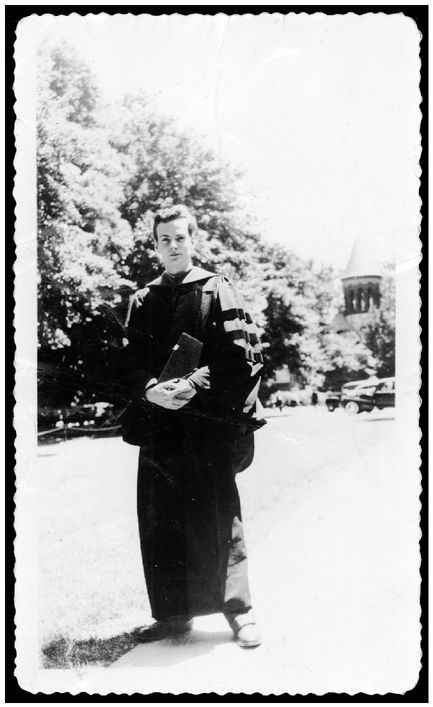

TOP At the Princeton Library, 1939.

BOTTOM Arline Greenbaum, c. 1939.

You must come visit me, Mom, some time.You wrote me saying you wanted to, and if I know you, and I think I do, a little, you’ll never quite get around to coming up—unless I keep pushing you. How about a date? Write in your next letter which week-end you’re coming up definitely.

My academic life has its usual characteristic of being “not write home-able.”

However, last week things were going fast and neat as all heck, but now I’m hitting some mathematical difficulties which I will either surmount, walk around, or go a different way—all of which consumes all my time—but I like to do very much and am very happy indeed. I have never thought so much so steadily about one problem—so if I get nowhere I really will be very disturbed—However, I have already gotten somewhere, quite far—and to Prof. Wheeler’s satisfaction. However, the problem is not at completion although I’m just beginning to see how far it is to the end and how we might get there (although aforementioned mathematical difficulties loom ahead)—SOME FUN!

Even if your door is closed and locked now I’m still serious when I say it’s fun.

Tell Pop I have made out a time schedule so as to efficiently distribute my time and will follow it quite closely. There are many hours when I haven’t marked down just what to do but I do what I feel is most necessary then—or what I am most interested in—whether it be W.’s problem or reading Kinetic Theory of Gases, etc.

And while you’re telling Pop, give him this problem in LONG DIVISION. EACH OF THE DOTS REPRESENTS SOME DIGIT (ANY DIGIT). EACH OF THE A’S REPRESENT THE SAME DIGIT (for example, a 3) NONE OF THE DOTS ARE THE SAME AS THE A (i.e., no dot can be a 3 if A is 3).

Love,

R.P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO LUCILLE FEYNMAN, OCTOBER 1940

Oct. ? 1940

Dear Mom,

I never didn’t write a letter in such a long time before. I don’t know why—but I never got around to it.

Thanks very much for answering my telegram. I will register on Tuesday for voting (Wed. for draft).

Putzie is coming up to visit me tomorrow.

1I am listening in to a course in physiology (study of life processes) in the biology department. It’s a graduate course—I didn’t realize how much I really picked up reading all about those things on my vacations. I don’t know at all as much as the 3 other fellows in the course but I can understand and follow everything easily.

The night you left I had a fellow visit me and we finished the rice pudding and most of the grapes. I finished the grapes the next day.

A few nights later two mathematicians came to visit. We had crackers and peanut butter and jelly and pineapple juice. I had a lot of trouble opening the can because I didn’t have a good can opener.

The next day I received a present of a dandy can opener from the mathematicians. A practical gift—I suppose.

Night before last a fellow came in and we had tea and crackers. I can boil water pretty well now because I bought a pot cover.

It’s a lot of fun.

Well, I’d better get to work.

Love,

R.P.F.

ARLINE GREENBAUM TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, JUNE 3, 1941

Richard sweetheart I love you—maybe more than I can ever tell you—and perhaps we can find a still happier plan of living—besides my happiness we must consider yours—we still have a little more to learn in this game of life and chess—and I don’t want to have you sacrifice anything for me—tomorrow Dr.Treves is going to see me and tell me, according to “Woody” (Dr.Woodwood) some news—I wonder if he’s going to give me that story about “glandular fever” that you said “Woody” had planned to tell me—I’ll swallow it but Nan wrote and said I had the right to call in another doctor to check the diagnosis and have him look at the slides from the biopsy—she recommended a man too—I’ll look into it before you come home this weekend and we could see him together—I know you must be working very hard trying to get your paper out—and do other problems on the side—I’m awfully happy tho’ that you’re going to publish something—it gives me a very special thrill when your work is acknowledged for its value—I want you to continue and really give the world and science all you can—if I were an artist I’d give all I could to art—but all I can do is draw a little—darling I love you—and if you receive criticisms—remember everyone loves differently—but I’ll always do my best for you—your happiness is as important to me as mine is to you—the problem we’re faced with confused even Aristotle. “What is the chief ‘good’ of man”—Darling I’ll always belong to you—and always love you—no matter where or when—

I’m your

Putzie

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO LUCILLE FEYNMAN, MARCH 3, 1942

There is a scrap of paper from his mother’s letter taped to the first page of his response. It reads:

You wrote: I get $60

pay laundry $18 + 2

Memberships $13 + 3

Mother $10

Remainder $19

Oh! Richard! How fallen art thou!!

I make it $14

Woe is me! Who will

Balance my checkbook?

Dear Mom,

I will balance your check book.

If you will look more carefully at my last letter you might find something such as “I get $60 I pay 1. Laundry $18 and 2 membership $13 and 3 Mother $10.” The 2 and 3 are numbers which are used to number the items, and I didn’t mean them to be added in.

My bill for $265 came (or did I tell you). I spent 20 minutes figuring out which of my certificates at the Postal Savings I should cash in in order to get the maximum interest. I can get a maximum of 53¢. This was interesting until I discovered that if I did it the worse way, and got the least interest possible it would be 45¢. I think 20 minutes of my time ought to be worth more than 4¢. (In order to dispel more slurs on my calculating ability might I say that the 4¢ is right. If I didn’t figure it out at all and did it at random on the average I might expect to come out with about 1/2 way between the most possible (53¢) and the least (45¢) or I should expect if I didn’t figure I would get about 49¢. Since I get 53¢ by figuring I save 4¢ on the average by figuring for 20 min. It’s all in the laws of chance that the 8¢ becomes 4¢).

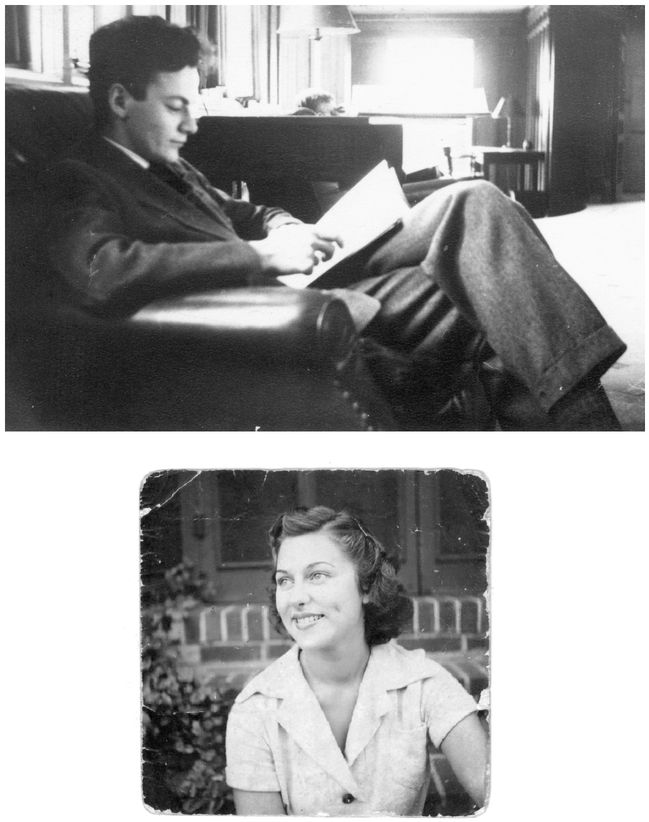

Feynman, 1942.

Princeton pays me 10¢ for 20 minutes figuring on a 48 hr week. (OK, 10 5/12¢, or make it 10¢ figuring on a 50 hr week).

Now I hope your little door is slammed shut.

There isn’t much else to tell about, except the letter from Pop which you know all about and which I answered today.

Love Richard

P.S. Wishing you a happy anniversary and Joan a happy birthday—in case I forget later.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO MELVILLE FEYNMAN, JUNE 5, 1942

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN

PRINCETON GRADUATE COLLEGE

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY

Dear Pop,

As you suggested, I asked Prof. Smyth about how he thought my marriage might affect my career. He said the only thing he could think of is that possibly some might not hire me because they figured I carried too much of a burden. He said, however, that he tries as much as possible to keep out of people’s private affairs and that it didn’t make any difference to him at all, and he supposed it probably wouldn’t make much difference to others.

I then pointed out that I would be in contact with an active case of T.B. and so he might not think it a good idea for me to teach, because it might affect the students. He said he had not thought of that at all, but, since he didn’t know too much about T.B., he would call the University Doctor—Doctor York.

He told me later that he called Dr.York, and that Dr.York said that as long as the girl was in a sanatorium there was no danger to my students and myself. He said Dr.York would like to speak to me. I went over to talk to him today.

The doctor said he heard I had a little problem, and that he’d like to know if I knew a few things. First he told me that one of the most important things for a T.B. patient was freedom from worry, etc.—what he called emotional security. I told him I realized this and that it was one of the important reasons for my getting married—because she would worry far less if she were married, than the way things are now.

Then he asked if I knew that it would be very bad for an active case of T.B. to become pregnant. I said yes, again—and told him there would be no chance of it.

He said these were the main things he wanted to say and he wanted to find out if I had thought about them—and also the fact that T.B. is not always curable. He said he wanted to find out if I was responsible and I had thought about these things.

Then we discussed all kinds of things—how Arline was getting along—how long she would have it—etc.We spoke about where to put her and he warned against private places (except for a few like Saranac—which is too expensive). He asked me what the parents thought and I told him her parents saw no objection, but that mine were worried about my getting infected and indirectly carrying the germ around and infecting others—and for this and many other reasons they didn’t like the idea.

He said I should understand T.B. is an infectious disease but not a contagious one (I asked him what he meant by that—the idea is the germs don’t float all around in the air and you don’t get it just on contact—etc. I didn’t understand the difference very well—apparently it’s one of degree). He said that I had less chance of getting sick in the sanatorium visiting her than when I was out in the street—because in the sanatorium they take precautions to burn the sputum, but careless people in the street just spit all around. I think he was exaggerating, but I still think you shouldn’t worry that by marrying I lay myself and my friends open to a great danger.

Love from

R.P.F.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO LUCILLE FEYNMAN, DATE UNKNOWN, JUNE 1942

The following letter is in response to one from Lucille, Richard’s mother, in which she lovingly but forcefully outlined her concerns about Richard’s intent to marry Arline. Arline’s illness, she feared, would compromise not only his own health but his career. She was also concerned about the high cost of treatment (for oxygen, specialists, hospitalization, and so on).

Lucille suggested that his desire to marry stemmed from his desire to please someone he loved (“just as you used to occasionally eat spinach to please me”) and recommended that they stay “engaged.”

Richard’s response came on the same embossed stationary as his previous letters, with “Ph.D.” added in ink following his name.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, Ph.D.

PRINCETON GRADUATE COLLEGE

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY

Graduation from Princeton, June 16, 1942.

Dear Mom,

I really should have answered you sooner, but I have been spending the last few nights working on physics problems—and now that I’m stuck for a while I’ll take time out to write to you.

I enclose your letter so you will remember which point is which that I refer to.

With regard to (1) and (2) I went to see Prof. Smyth at Pop’s suggestion and the doctor here at the university.The doctor said I have less chance of getting T.B. in the sanatorium when visiting her than when I am walking around in the street. I think he was exaggerating (all this is in detail in a letter to Pop, so I won’t repeat it all here). He said T.B. is infectious but not contagious—I didn’t understand the distinction he made, however. Ask Dr. Sarrow. He said in sanatoriums the patients take care of their sputum by cups or Kleenex for the purpose, but on the streets people are careless and just spit all around and when it dries the germs float into the air. He said the germs are not floating around in the air in a sanatorium. He said a lot has been found out about this in the last 25, and in particular the last 10, years. I would be no danger to my students. Prof. Smyth didn’t see any objection from his point of view to hiring me if my wife is sick.

(3) If no one can make a budget for illness, how can I ever make enough to pay for it? How much is enough? Some guesses must be made and I guess I have enough. How much would you guess would be necessary?

(4) I wouldn’t be satisfied being engaged any longer. I want the burden and responsibility of being married.

(5) It really wasn’t hard at all.While I was out to lunch while waiting for somebody to come back to the courthouse in Trenton, I found myself singing—and I realized then that I really was very happy arranging things. It was, I suppose, the pleasure of arranging things for our life together—before she was sick we used to talk of the fun it would be going around ringing doorbells looking for a place to live—I guess it was similar to that idea.

I am not afraid of her parents—and if they don’t trust me with their daughter let them say so now. If they get sore at my mistakes later, it’s too late and it won’t bother me.You are right about my lack (4) of experience—I have no answer to that.

(6) The cost here again is a guess. I want to take the chance, however, that it will be sufficient. If it isn’t I’ll be in difficulty as you suggest.

(7) I’ve already been employed at Princeton for the next year. If I must go elsewhere, I’ll go where I’m needed most.

(8) I do want to get married. I also want to give someone I love what she wants—especially because at the same time I will be doing something I want. It is not at all like eating spinach—(also you misunderstood my motives as a small boy—I didn’t want you angry at me)—I didn’t like spinach.

(9) This is the problem we are discussing—I mean whether marriage is worse than engagement.

(10) I’m honestly sorry it makes you feel so bad. I bet it won’t be too heavy.

Why I want go get married;

It is not that I want to be noble. It is not that I think it’s the only right, honest and decent thing to do, under the circumstances. It is not that I made a promise five years ago—(under entirely different circumstances)—and that I don’t want to “back out” of the promise. That stuff is baloney. If anytime during the five years I thought I’d rather not go thru with it—promise or no promise I’d “back out” so fast it would make your head spin. I’m not dopey enough to tie up my whole life in the future because of some promise I made in the past—under different circumstances.

This decision to marry is a decision now and not one made five years ago.

I want to marry Arline because I love her—which means I want to take care of her.That is all there is to it. I want to take care of her.

I am anxious for the responsibilities and uncertainties of taking care of the girl I love.

I have, however, other desires and aims in the world. One of them is to contribute as much as to physics as I can.This is, in my mind, of even more importance than my love for Arline.

It is therefore especially fortunate that, as I can see (guess) my getting married will interfere very slightly, if at all with my main job in life. I am quite sure I can do both at once. (There is even the possibility that the consequent happiness of being married—and the constant encouragement and sympathy of my wife will aid in my endeavor—but actually in the past my love hasn’t affected my physics much, and I don’t really suppose it will be too great an assistance in the future.

Since I feel I can carry on my main job, and still enjoy the luxury of taking care of someone I love—I intend to be married shortly.

Does that explain anything?

Your Son.

R.P.F. PH.D.

P.S. I should have pointed out that I know I am taking chances getting married and may get into all kinds of pickles. I think the chances of major disasters are sufficiently small, and the gain to me and Putzie great enough, that the risk is well worth taking. Of course, this is just the point we are discussing—the magnitude of the risk—so I am saying nothing but simply asserting I think it is small.You think it is large, and therefore I was particularly anxious to have you tell me where you thought the pitfalls were—and you have pointed out a few new ones to me. I still feel the risk is worth taking—and the fact that we differ is due to our difference in background, experience and viewpoint. Please don’t worry that, by explaining your viewpoint, you have in any way pushed us further apart—you haven’t. I only hope that my marrying directly in the face of your disapproval and your better judgment won’t alienate you from me—because honestly, our judgments differ and I think you’re wrong. I honestly believe we (Putzie and I) will be better off married and nobody will be hurt by it.

RPF

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO DAN ROBBINS, JUNE 24, 1942

Mr. Robbins was a fraternity brother of Feynman’s. The project in question in this letter was the early phase of the race to build the atomic bomb. Feynman had received a letter a few days earlier from researchers at the University of Chicago asking whether he was interested in working on what they could only describe as “research and development work on new methods of military offense and defense.”They promised that this work would be a vital factor in the successful conclusion of World War II. Feynman later recalled how Professor Robert Wilson came to his office at Princeton to encourage him to enlist in the project. He signed on shortly thereafter.

Dear Danny,

I wrote a letter to the fraternity recently—and I tried to call you up at your home. I spoke to your mom. She tells me you are already working on a defense project at M.I.T.

I wanted to write to you especially to reitterate (how do you spell it?) to you personally the offer of a job with our group at Princeton.

The darn trouble is I can’t go into any detail about what the work concerns and what we need you for. It makes it hard for me to explain or make the opportunity seem good—except in general,—and therefore (for me at least) weak, terms.

(Up to this point I’ve just copied stuff from another letter I just wrote to you but won’t send because I told you so much about the job—indirectly that I think one could have guessed pretty closely what it was—I hope I avoid writing again and make no more mistakes).

I can only say I find the job very exciting, because the results are of such enormous consequence.You really feel you are fighting right alongside the army and you hope you can get it done in time—in time means before the other side works it out.

I’m doing most of the theoretical figuring. I try to figure out what should happen for various conditions and what the best way to build this part or the other is. I don’t know if you were most interested in theoretical or experimental work or both—but we can use you and we will listen to all your ideas—(because we need more ideas) in any capacity. I urge you to come.

In making a decision, however, I can see you have a considerable problem because you are already working on a defense project. I would say the important thing is to do that work that you think will contribute the most to the war effort.Your mother said you seemed tired of the environment up there at M.I.T. and might like it out here much better. I’d like to see you and work with you too—but I don’t think such personal matters carry any weight.The real thing is your usefulness. Make that as great as possible.Your problem is hard because I can’t tell you what kind of work there is here and you can’t tell where you’ll be the most useful—here or there. If you are interested and think you might advantageously make the change but are not sure we may be able to get the opinion of someone who knows about both jobs—the one you’re on and this one.

How is your personal life?

I am getting married in a few days to Arline Greenbaum (also known as Putzie). I just got my Doctor’s degree. I also just got a job as a visiting associate professor at the Univ. of Wisconsin for one year—on leave without pay to do war work (it sounds silly but the idea is I’ve got the job if the war work stops).

Can I hear from you soon?

Brother R.P. Feynman

Mr. Robbins was not able to accept this job offer, as he had already accepted a commission in the U.S. Navy.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO LUCILLE FEYNMAN, DATE UNKNOWN, 1942

DR. RICHARD P. FEYNMAN

PALMER PHYSICAL LABORATORIES

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY

Dear Mom,

I won’t write you a long letter for I haven’t time. Putzie wanted me to write to you and her mom to tell you to excuse her for her not writing this week as she feels sick.Would you call up her mom and tell her?

Mr. and Mrs. Feynman, June 29, 1942.

You ask for a letter about myself and what I’m doing. All the letters so far were on just that subject—at least what plays I saw, etc. Other times life is very simple.

This week has been unusual.There is an especially important problem to be worked out on the project, and it’s a lot of fun so I am working quite hard on it. I get up at about 10:30 AM after a good night’s rest and go to work until about 12:30 or 1 AM the next morning when I go back to bed. Naturally I take off about 2 hrs for my two meals. I don’t eat any breakfast, but I eat a midnight snack before I go to bed. It’s been that way for 4 or 5 days. Usually I don’t work nearly as hard—more like 7 1/2 or 8 hours a day.

The only difference from one day to the next is that some days when I go to lunch I take my laundry out and some days when I come from lunch I bring my laundry back.

Hey, what’s this about Frances and 4 AM?

2 When I’d stay out that late you (or at least Pop—I never could remember which of you bawled me out for which offense) used to say you don’t see how Arline’s parents permit her to stay out so late, etc., etc. . . Isn’t Frances partly in your charge when she visits from N.Y.? Perhaps I shouldn’t remind you or Frances will get angry.

Mooseface is next, and I expect her to come in at dawn every day.

3 You can’t call her down, however—you can ascribe it all to her interest in astronomy. She had better get used to staying up during the night because there are few stars visible in the daytime. Heck, wait until you become a Red Cross Night Nurse or Night Staff Assistant or what have you, then the only one who will see the green of the trees, etc. in the daytime will be Pop when he comes home from a Saturday day of rest. He’ll probably go to sleep on the beach anyway.

I’d better shut up, it is 1:45 AM now.

Love to Everyone