1946-1959

After the war, Feynman decided not to take the position that the University of Wisconsin had been holding for him and instead opted for a post at Cornell. His father died in October 1946, little more than a year after Arline’s death. It was a bleak time in Richard’s life, and this is reflected in the relatively listless tone of many of the letters written during this period. As he later described his state of mind at the time:

I had a very strong reaction after the war of a peculiar nature. It may be from the bomb itself, and it may be for some other psychological reason. . . .Already it appeared to me, very early, earlier than to others who were more optimistic, that international relations and the way people were behaving was no different than it had ever been before, and it was just going to turn out the same way as any other thing, and I was sure that it was going therefore to be used very soon. . . .This was before we knew that the Russians were quickly developing one, but there was no doubt in my mind that they could develop one. What one fool can do, another can.

9

Professionally, however, he was coming into his own. His attendance of the Shelter Island conference in 1947—Edward Teller, Hans Bethe, Abraham Pais, Isidor Rabi, John von Neumann, John Wheeler, Julian Schwinger, Linus Pauling, Willis Lamb, and Robert Oppenheimer were among the twenty-four attendees—helped solidify his position among the leaders in his field. Feynman’s papers on quantum electrodynamics, the work that eventually won him the Nobel Prize, also date back to this period.

In 1950 he accepted a position at Caltech—spending his first year on sabbatical in Brazil. Much of the correspondence from the following years revolves around purely professional concerns: asking for help in finding errors in an academic paper and sending his regrets when asked to return to Los Alamos. His efforts and achievements were recognized with the Albert Einstein Award in 1954. The arrival of Murray Gell-Mann at Caltech soon thereafter subsequently generated a fruitful—and now legendary—collaboration and rivalry.

In 1958, my mother, Gweneth Howarth, came to America at my father’s urging. Unfortunately, little of the correspondence between them has survived, though it is clear from his letter of May 29 of that year that Gweneth was an adventurous woman—daring enough to move across the Atlantic to be his housekeeper after the briefest of relationships.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO R. C. GIBBS, OCTOBER 24, 1945

Prof. R. C. Gibbs

Department of Physics

Cornell University

Ithaca, New York

Dear Professor Gibbs:

When I heard, a few weeks ago, that Mr. Bethe had nearly decided to go to Columbia, I was very disturbed and did my best to try to get him to stay at Cornell. The reason I chose to go to Cornell a year ago was that I wanted to go to a school where there was an active experimental group doing research in nuclear physics. Only in this way could I keep abreast of progress by means of the theoretical problems and questions which could arise in connection with the experimental works. At that time, I was looking forward to working with Dr. Bethe and having an experimental group of such men as Bacher, Rossi, Parratt, Greisen and we were thinking of McDaniel and Baker also. If, however, Dr. Bethe did not go to Cornell then Bacher and Greisen would not go (Rossi had already decided not to return) and I didn’t see how we could attract other young men with so little to offer. I decided to come on November first as planned anyhow because the date was so late and you had been counting on it. But I did intend to tell you that I wanted to stay as short a time as possible.

I know many young men here whom we should want at Cornell and have spoken to them about the situation. I have had very little success when it was assigned that neither Dr. Bethe, Bacher nor Greisen would be there. On the other hand, if we assumed that these men would be there and described the program we had in mind, they were very interested. Unfortunately, they also have other offers and are being pressed so that they are impatient with the uncertainty at Cornell. We have already lost one very good electronics man in this way.

So it seems to me there are just two possibilities. Either Dr. Bethe (and therefore, Bacher, Greisen and other young men) go to Cornell, and the department is one of the best in the country, or else the Physics Department will find itself in such a poor state as to be unable to attract the abler of the young physicists who are now being released from war work.

I am, therefore, in favor of anything which will result in the first alternative. This means, I believe, that Professor Bethe would be chairman of the department after your retirement. From the point of view of administration of the department and the control of policy, I think this would be a very good thing. Dr. Bethe has done a wonderful job as leader of the Theoretical Division here. He managed this with remarkable facility. Everyone felt free to work on whatever he wished, yet all the work was coordinated and the job was done. And you can understand that the policy of the entire project very often depended on Theoretical conclusions. There should be absolutely no doubt as to his abilities as an administrator.

On the other hand, it would be unfortunate for physics, indeed, if he were to spend a very large fraction of his time away from research. Therefore, I think he should have a vice-chairman who could take up as much as possible of the purely administrative duties.

I do hope that you can find some such arrangement which is satisfactory to all. It is important that this be done as quickly as possible. I am looking forward to becoming an active member of an active Physics Department.

Sincerely,

R. P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO ROBERT OPPENHEIMER, NOVEMBER 5, 1946

Professor J. R. Oppenheimer

Department of Physics

University of California

Berkeley, California

Dear Oppy:

It looks black for my proposed visit to California.

Cornell is all loaded up with graduate students.There are many more than ever before, and we have all we can do to handle them. The department was, therefore, very reluctant to let me go for the spring semester, as I was needed to help handle the load.

There is another personal reason. My father has died and I do not want to go too far away from my mother in New York, at least for a while.

I was looking forward very much to my visiting you at Berkeley, as you know. I am sorry to have to disappoint both myself and you. I had been hoping to see many friends again, but that is the way things go.

Sincerely,

R. P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO R. D. RICHTMEYER, APRIL 15, 1947

After receiving an inquiry as to whether he would be interested in returning to Los Alamos as a consultant for ten weeks during the summer and whether he was interested in attending a nuclear physics conference still in the planning stage, Feynman wrote the following response.

Mr. R. D. Richtmeyer

Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory

P.O. Box 1663

Santa Fe, New Mexico

Dear Bob:

My plans for the summer are not very definite. I expect to loaf around a great deal and I do not know whether I will be through New Mexico.

However, I do not think that I will have time to do any work at Los Alamos in the near future so I would just as soon not bother about filling out all the blanks for the contract until there is some definite reason for it.

Sincerely yours,

R. P. Feynman

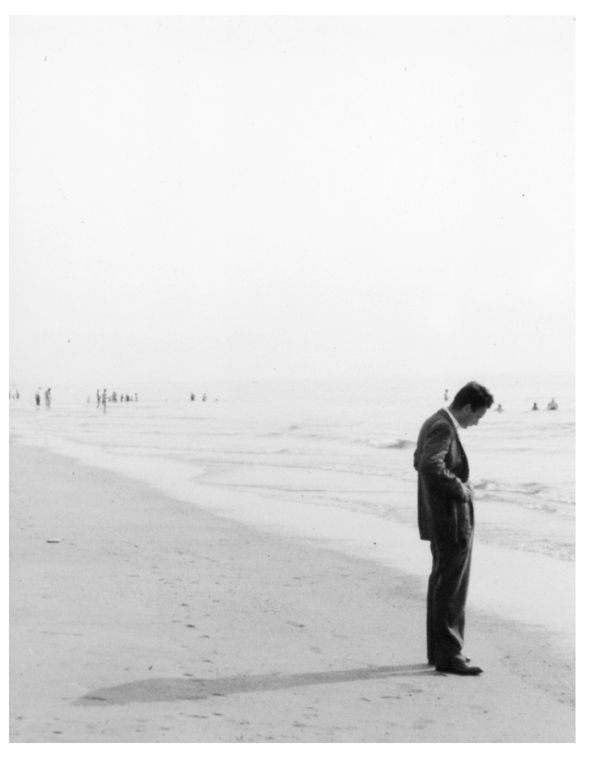

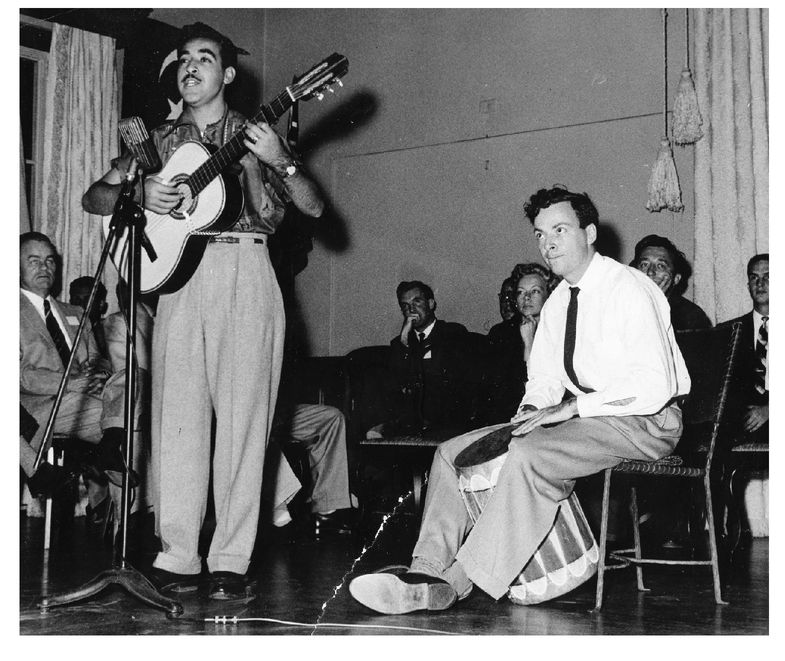

Teaching at Cornell, 1948.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO E. O. LAWRENCE, JULY 15, 1947

Professor E. O. Lawrence

Radiation Laboratory

University of California

Berkeley, California

Dear Professor Lawrence:

I have just written to Professor Birge to tell him that I will not be in California next year.

It was really an awfully difficult decision to make but everything seemed to balance out except the weather and the fact that I was already settled at Cornell. Neither of these seemed like a very important consideration so I have had a lot of trouble in finally making up my mind.When I heard that Weisskopf was not going to be at Berkeley, I finally decided that I would stay at Cornell next year.

I don’t know how to thank you for the really glorious time I had in California. Probably, it was just the kind of time everyone always has in California but it seemed to me to be especially good. Please wish my best to Serbeis and MacMillans as well as to your wife and kids and thank them very much for making my stay there so enjoyable. No doubt somehow, we will all see each other again.

Sincerely yours,

R. P. Feynman

JACK WILLIAMSON TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, MARCH 25, 1949

Jack Williamson, who published his first story in 1928, was in the early stages of a long and illustrious career in science fiction.

Dear Professor Feynman:

This is to ask your opinion of a notion about the nuclear binding forces—that they may not be actual forces, but instead a consequence of the nature of space-time.

If space-time is an effect of the mass it contains, might it not be composed of ultimate units somehow reflecting the quantum nature of individual particles? And might those minimum units or packets of space-time be of such a nature that the disruptive force of electrostatic repulsion cannot act inside any packet, but only between different packets?

And might the atomic nucleus then be composed of one such unit of space, shaped by the particles it contains?

It would follow that energy is required for the formation of these units of space—a different amount of energy for each number and arrangement of contained particles, the mechanism being such as to account for the packing fraction curve and all the complicated phenomena of nuclear masses and energies.

One helium nucleus, for the simplest example, requires only one unit of space-time in which to exist, so that the formation of a helium nucleus from four hydrogen nuclei liberates the energy of the three surplus packets. (Neglecting the amount of energy involved in altering that one packet to hold four particles instead of one.)

The stability of such a nucleus would not be due, then, to any actual force binding the parts of it together, but instead to the two conditions that, first, the repulsive force cannot act inside the unit of space-time containing it, and, second, the parts cannot separate without acquiring energy to form additional units of space-time to contain the fragments.

The instability, on the other hand, of such massive nuclei as those of radium and uranium would be due to the circumstance that the packets of space-time containing them have become overfilled, to the extent that energy is available, from that spent in enlarging them, to form separate packets for an alpha particle or the fragments of fission.

If really successful, this idea of course ought to account for such other entities as electrons and mesons.An electron might be an empty or substantially empty packet, therefore representing much less mass and energy—it might be the actual quantum of space-time. I don’t, however, see any simple answer to the problem of the meson.

The mathematical relationship of such units of space-time to their sum or effect in the more familiar space-time of the macrocosmic universe—that relationship, it seems possible to me, might help to bridge the gap which now exists between quantum mechanics and the relativistic physics of the macrocosmos.

However, I am not a mathematician—which of course means that I am unable to develop this idea or to assay its value, if any. I am not even sufficiently familiar with the technical literature to be sure that it is new. It does seem to me to have a certain plausibility, as well as the logical advantage of avoiding the need of any separate kind of force to contain nuclear energy.

I should be very grateful for any comment which you might have the time and inclination to make on this suggestion.A stamped envelope is enclosed.

Yours sincerely,

Jack Williamson

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO JACK WILLIAMSON, MAY 30, 1949

Mr. Jack Williamson

Portales, New Mexico

Dear Mr.Williamson:

I was interested in your idea concerning the binding of nuclear particles but I did not find it stated precisely enough to be able to understand it. What I mean is that I do not see how one would explain the mathematical relations of the units of space-time, etc.

As you know, a theory in physics is not useful unless it is able to predict underlined effects which we would not otherwise expect. I do not think that your idea is sufficiently developed to enable that to be possible.

As an example you may explain the instability of massive nuclei as those of radium and uranium due to circumstance “that the packets of space-time containing them have become overfilled.”The question is would you have expected that they become overfilled when we get to nuclei as massive as radium and uranium? Why are they not overfilled for atoms of copper or iron? The question is a quantitative one in order to determine exactly which atoms are massive enough to be unstable.

I hope I do not discourage you too much in thinking about these things but I would suggest that you try to make the ideas as definite and precise as possible.

Sincerely yours,

R. P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO T. A. WELTON, NOVEMBER 16, 1949

Professor T.A. Welton

Department of Physics

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Dear Ted:

Right now I don’t feel much like giving a colloquium at all. I am trying to write up some more of my stuff and I would like to have time just to stay in one place and work. On the other hand I would like to see you again some time so I don’t know what to say.Why don’t you try me again sometime next semester when I am sick and tired of working?

I am enclosing reprints of my papers. I gather from your letter that you did not try to read then because if you had I assure you would find them very simple, at least if you don’t try to prove that all the things I say are correct. You know how I work so most of it is just a good guess. All the mathematical proofs were later discoveries that I don’t thoroughly understand but the physical ideas I think are very simple. Start with the one about positrons. I wish you luck.

Sincerely yours,

R. P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO JULIUS ASHKIN, JUNE 5, 1950

Professor Julius Ashkin

Department of Physics

University of Rochester

Rochester, New York

Dear Ash:

I am sending you a manuscript of my next paper. I was just hoping that you would have time to read it and to discover all the errors as you were so kind to do on the other two papers that I wrote. I and the printer have the only other two copies so it is a very valuable thing. However, if you do not want to study it so carefully you may still have it as a prize for being so good to me last time.

On the other hand, if you have no time to read it at all and are not interested, would you please send it back because Professor Bethe wants a copy for a course he is going to teach this summer and all I can give him is the typist’s manuscript.

I would appreciate any comments you have to make on it. I will send you a copy of my next paper from California.

On cleaning my desk I discovered a little note telling me to send a bill for my expenses to the seminar at Rochester. I don’t have the courage to send the bill so late so I am sending it to you with a mild hope that I can get $22.00. If, however, it is too late and causes a lot of confusion, please do not worry about it because I am well paid in California. Thanks very much.

Sincerely,

R. P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO M. L. OLIPHANT, DECEMBER 12, 1950

Prof. M. L. Oliphant

Australian National University

Canberra, Australia

Dear Professor Oliphant:

I have received your kind letter and that of Ernest Titterton telling me of the fine opportunity in Australia. I have thought it over and decided not to accept.

I am very interested in attempts to begin research in other parts of the world. I want to wish you great success. I am spending next year in Brazil in connection with an analogous development.The present concentration of research facilities and scientific universities has obvious dangers.

Sincerely,

R. P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO JERROLD R. ZACHARIAS, JANUARY 18, 1951

Dr. Jerrold R. Zacharias, Director

Laboratory for Nuclear Science and Engineering

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Dear Zach:

I am writing this letter to save you a telephone call in answer to your proposition to use my nasty mind with Intelligence.

I have decided against doing this.The reason is I do not believe that my talent is sufficiently unique in this direction. I think my abilities and training as a physicist probably has a more direct use in some other (but as yet unknown) way. I suspect that there are plenty of ingenious people able to deal, as well as I, with the problems that you mention, who are at present employed as anything from sales-manager to criminal.

Thank you for considering me for the job, however. Frankly my position would be stronger if I saw something I could actually do directly with physics. Maybe physics in its own right has some value since the national emergency is not yet complete war.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

JOHN WHEELER TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, MARCH 29, 1951

Professor Richard Feynman

Norman Bridge Laboratory

Calif. Institute of Tech.

Pasadena, California

Dear Dick:

I know you plan to spend next year in Brazil. I hope world conditions will permit. They may not. My personal rough guess is at least 40 percent chance of war by September, and you undoubtedly have your own probability estimate.You may be doing some thinking about what you will do if the emergency becomes acute.Will you consider the possibility of getting in behind a full scale program of thermonuclear work at Princeton through at least to September 1952?

Los Alamos has asked Princeton to pitch in on this business. I am returning there full time the end of May to push it. Spitzer, Schwartzschild, Ford and Toll are going to give half to full time. Others are going to give part time. Spitzer, Hamilton and I are engaged in active recruiting. The university has made available a large separate building. Los Alamos has prepared a draft contract. John von Neumann, Goldstein, and Richtmeyer will be actively concerned with the work, especially as involves the Princeton MANIAC. The Princeton development far from representing a downgrading of the Los Alamos effort has been requested to help Los Alamos get even more done. I can’t discuss feasibility in this letter, nor a number of exciting new ideas which have been churning about here the last weeks. They are along a line rather different from that which Bob Christy plans to follow. Both Edward Teller and I would like to describe them to you in person to see if you don’t think it is urgent for the defense of this country that most promising of these schemes be developed as soon as possible.

The following reasons make me think you might wish to give serious consideration to this request for your help:

1. Already without the benefit of thermonuclear oomph, atomic bombs form a major part of this country’s war potential. At peak production during War II we turned out about 4 kilotons a day in conventional high explosives. In the crude and highly arbitrary measure of total energy release this output means one fifth conventional atomic bomb per day, or in 700 days, 140 old fashioned atomic bombs. For comparison take any newspaper guess as to atomic bomb output.Then ask if there is any justification for the hair-shirt philosophy of many nuclear physicists—“Nuclear physics is interesting; therefore we mustn’t work on it in case of war; it’s better to forget physics and tell the admirals and generals how to do tactical and strategic this-and-that.” Clearly there’s a lot to be done in such directions. One may even achieve a factor of two gain. But what business has the country’s best physicists fooling around with a factor two when factors of five and twenty are at stake? If they do, the country may feel in return it ought to give atomic weapon development to the generals!

2. Princeton’s job is to be idea factory and do primordial design, Los Alamos to work in these fields, too, but also to carry things through all the practical stages right to the end.The shortage of people on the idea assessment and primordial design end is to me terrifying.You would make percentage-wise more difference there than anywhere else in the national picture.

3. We intend to get together at Princeton, a group of supercritical size that will really get somewhere.

4. I’m planning to work full time and I would hope you might consider that, too, owing to the urgency of the international situation. However, there would be an alternative opportunity for as large a fraction of pure academic connection as you might feel appropriate if you don’t think the emergency has got to the full time stage yet.

Summarizing—

1. It would be enormously helpful if you could come now, either to Los Alamos or to Princeton.

2. If you feel the emergency isn’t yet at that stage, but may possibly soon get there, it would be very encouraging to us all if you would say that you will consider seriously pushing the thermonuclear business.

3. If your answer on (2) is affirmative, would you be willing to fill out the enclosed clearance forms to keep open the degrees of freedom for early participation?

4. And would you care to ring me collect at Los Alamos 2-2776, or write me, to let me know what your feeling is?

Best wishes,

John Wheeler

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO JOHN WHEELER, APRIL 5, 1951

Professor John Wheeler

P.O. Box 1663

Los Alamos, New Mexico

Dear John:

As you know, I was planning to spend my sabbatical leave in Brazil. I am uncomfortably aware of the very large chance that I will be unable to go. Until that situation becomes definite, however, I do not wish to make any commitment for work next year.

Best wishes,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO LUCILLE FEYNMAN, AUGUST 30, 1954

August 30, 1954

My Dear Mom;

You have nothing. A small room in a hotel. Stuffy and no home with friends and family in it.A job that gives no enlightenment or has no further aim than to be done each day, building nothing for yourself. No easy transportation but to be jostled by the crowds. Nor fancy meals, nor luxurious trips, nor fame nor wealth. Children who rarely write.You have nothing.

So say your friends, but they are wrong. Wealth is not happiness nor is swimming pools and villas. Nor is great work alone reward, or fame. Foreign places visited themselves give nothing. It is only you who bring to the places your heart, or in your great work feeling, or in your large house place. If you do this there is happiness. But your heart can be as easily brought to Samarkand as to the Hudson river. Peace is as difficult to achieve in a large house as in a small one. Feeling can be brought to any work.Your friends of wealth have nothing because of it that they would lose, if with more modest means.

In the sea of material desire that is our country you have found an inlet and a harbor.You are far from perfectly happy, but are as contentful as you can be, with your make-up in the world that is.That is a great achievement, or a great woman.

Why do I write this? Because you have told me these things many times, and I have nodded, vaguely understanding. But you mention them again and again, so perhaps you think I do not understand. For so few understand, each friend questions you, each relative hounds you with the query, how can you live in such a tiny place, how can you work in that unbearable shop with those horrible sales girls?You know how.They could never do it, nor can they live as contentedly in any other way, for they do not possess your inner strength and greatness. A greatness which has come to realize itself thru the knowledge that, beyond poverty, beyond the point that the material needs are reasonably satisfied, only from within is peace.

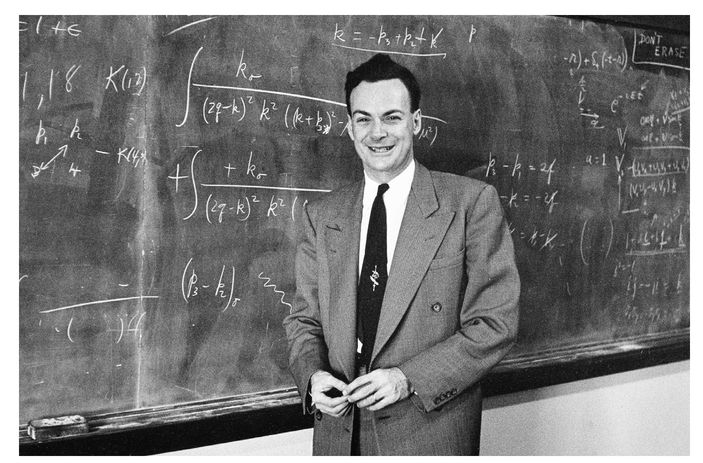

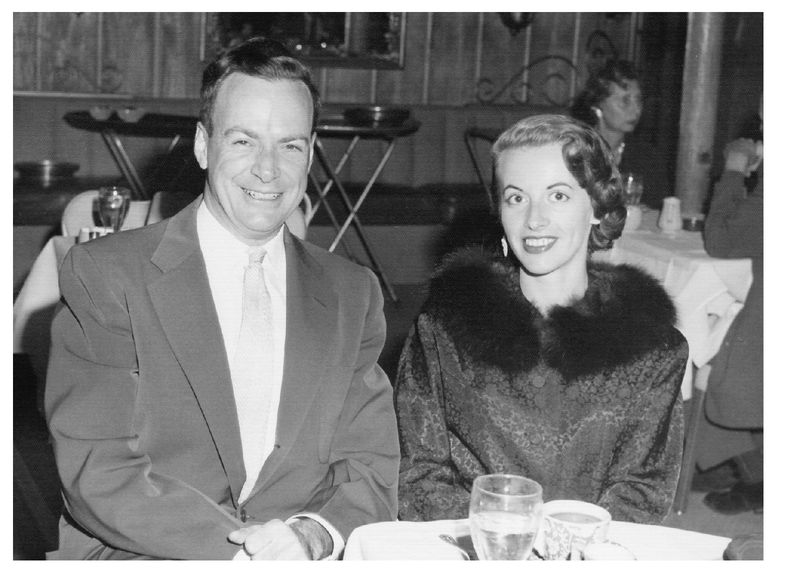

Richard and Lucille, mid 1950s.

I offer you all my resources of wealth.What do you want, what will you take? You can have anything $10,000 could bring you. I have offered many times. Not $10 worth can you think you need that you will let me give you. I bother you no more. I will never say it again, but you must always know that I will give you any material thing of wealth you could desire. Now or in my ability in the future.You have no insecurity. And tho you wrack your brains to think of something—not the smallest item suggests itself to you. No man is rich who is unsatisfied, but who wants nothing possess his heart’s desire. No need to concern yourself with friends’ attempts to help.You are not forced to live as you do.Your son’s offer proves that. It is your choice, your life, your simplicity, your peace and your contentment. It needs no further justification.

And I can offer all I own, even if I were selfishly doing so, for I know you want none of it.

When I offer it, what do you ask? You ask that I write to you.What can I give more easily, and am yet more stingy about? Tho I know your strength now requires nothing for its self-confidence,—tho I know you could live without my writing by accepting such a fact and living with it,—I do not desire to test your strength or to make your burden more heavy.What son has a mother who in such circumstances asks less of him!

My duty is clear, right action obvious. May I have the strength of resolve that this be the beginning of a more regular correspondence. I hope that the lesson of your strength in life will inspire me more often to try to add a bit you really want. I offer no more fans. If you want them ask. I hope I can write more often to a most deserving and inspiring woman. I love you.

Your Son.

The lack of correspondence from her son would eventually cease to be an issue. Lucille Feynman moved from New York to Pasadena, California, in 1959 to be closer to Richard.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO THE DEPARTMENT OF STATE, JANUARY 14, 1955

Department of State

Washington, D.C.

Gentlemen:

Yesterday I received a letter from Mr. Zaroubin, the Soviet Ambassador, inviting me to take part in a scientific conference in Moscow! A copy of the letter is enclosed.

This comes to me as a great surprise and I do not know what to do. Although the letter indicates that the conference is purely scientific, in the present relations of our country to Russia, such a visit by me obviously could have considerable non-scientific repercussions and be of interest to the Department of State. I would be very grateful to you if you could give me any advice. I should like to cooperate with your desires in this matter.

Does the Soviet invitation of foreign scientists represent a partial change of the iron curtain policy? Can we hope that this is a step back to more normal scientific relations with that country? Should we take advantage of such a change to find out what the scientists are thinking about and how healthy the scientific community is in Russia? Is there danger that I would be kept there and not permitted to return? I worked on atomic energy during the war, but not afterward. I am an expert on quantum electrodynamics and the theory of elementary particles, scientific fields which have no apparent military application at present, so it is not unreasonable that they would invite me if the invitation is above board.A further possibility is that it is partly as a consequence of a letter I wrote to the scientist Landau, commenting on some reprints he sent me. I enclose a copy of that.There was no answer. Are you aware of any other scientists being invited to this meeting?

I am willing to proceed in any way that seems to you to be in the best interests of the country, even if it should mean some personal danger.

Sincerely,

R. P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO THE ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION, JANUARY 14, 1955

Atomic Energy Commission

Washington, D.C.

Gentlemen:

Yesterday I received a letter from the Soviet ambassador inviting me to a scientific conference in Moscow! A copy of his letter is enclosed. I don’t know what to do about it, and have written to the State Department for advice.

I thought you would be interested because I was connected to the Los Alamos project during the war, so the danger that I might not be able to return, or the attitude of public opinion must be considered. Any suggestions you could make would be appreciated.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

TELEGRAM RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO THE DEPARTMENT OF STATE, FEBRUARY 17, 1955

Department of State

Washington, D.C.

Refer to my letter of January 14 asking your advice about invitation I received from Soviet Academy Sciences to visit Moscow for scientific conference. Zaroubin today says Soviet Academy will also pay travel expenses from USA to Moscow and back. I should like to answer as soon as possible to leave time for various arrangements. Could you please tell me your sentiments in this matter.

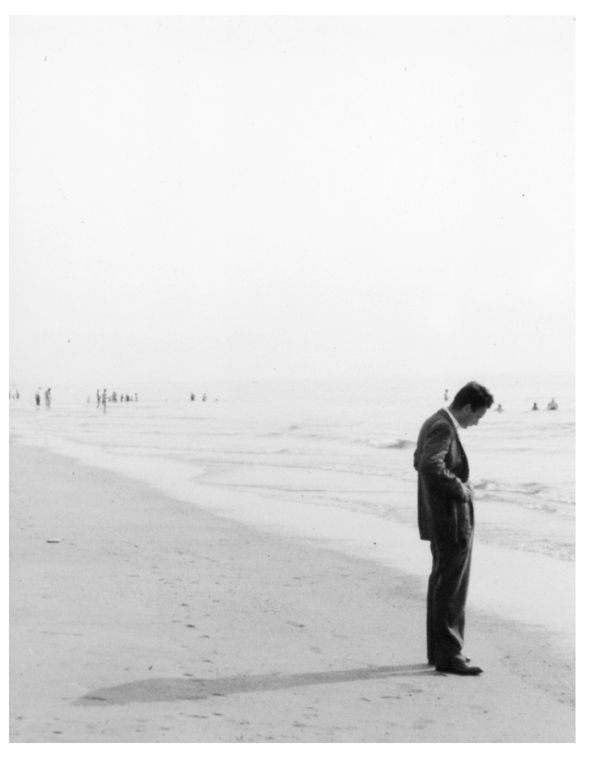

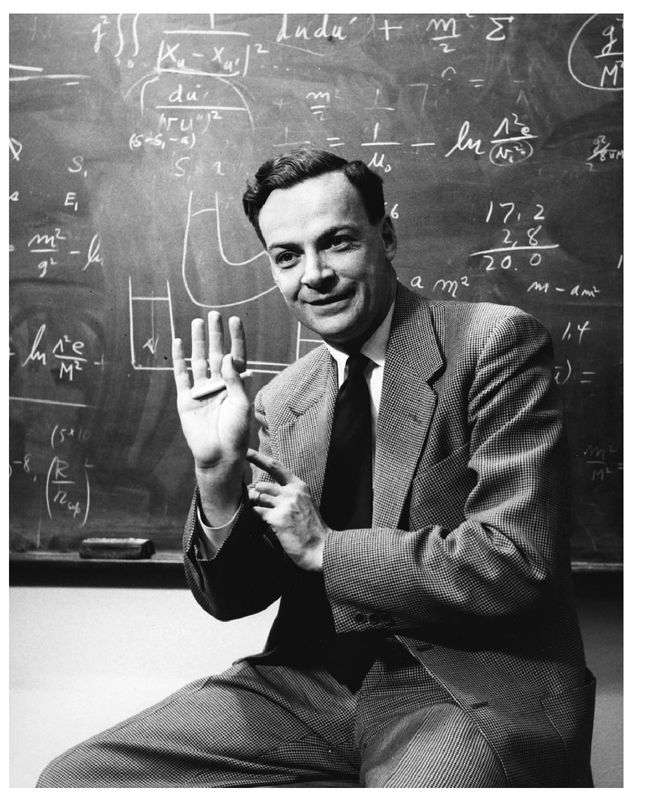

Classroom at Caltech, 1955.

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO WALTER RUDOLPH, FEBRUARY 24, 1955

Mr.Walter Rudolph

Department of State

Washington, D.C.

Dear Sir:

Over a month ago I wrote a letter to the Department (but not directly to your office) informing them that I was invited to a conference in Moscow on Quantum Electrodynamics and Elementary Particles.The invitation came through the Soviet Ambassador from the Soviet Academy of Science. It seemed to me that it may be of interest to the country and to science to encourage such exchanges and conferences. On the other hand, there might be good reasons, involving the relation of our country to Russia, why this may be a bad idea. I asked the Department for their view. I received no answer. Likewise a night letter sent last week went unanswered.

It is possible that these letters went astray, or were delayed because they were addressed to no one in particular, but to the Department in general. Dr. Koepfli, here, suggested that it would be much better if I wrote directly to you.

There is very little time left until the meeting.The meeting is March 31, and abstracts of papers to be presented should go in on March 1st. Furthermore, I would have to arrange air transportation and my passport and visa. Since I received no answer and some decision had to be made, I decided to accept the invitation. If there are any objections I hope you could register them immediately.

The passport I have is not valid for travel in Russia. Mr.Wallace Atwood, of the National Academy of Sciences, will soon bring it to the Department to get permission for such travel. I hope it doesn’t take too long.

I should like to emphasize again that I would like to cooperate fully with the Department. I would be perfectly satisfied with a refusal of permission to go, without feeling that any rights were violated. The situation between the countries is delicate and I am sure that you are far better at judging the repercussions of such a move than am I. On the other hand, if there are no objections I would like to go to the conference.

Could you please acknowledge this letter, even if no decision has yet been made, so I know at least whether this and the others have been received.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO WALLACE W. ATWOOD, JR., FEBRUARY 24, 1955

Mr.Wallace W. Atwood, Jr.

National Academy of Sciences

Washington, D.C.

Dear Mr. Atwood:

Thank you very much for the interest you have shown in my problem of getting to the conference in Moscow. I am especially grateful for your telephone conversation. I still haven’t heard from the State Department, however.

You were very kind to offer to see about my passport. I wish there were some other way to do it so that I wouldn’t bother you with it, but I am afraid to take the risk of getting it tied up. I called the passport division here in Los Angeles. They just laughed and said, “You can’t get a passport to go to Russia.”When I insisted they said to write to the Department of State directly.

So, I hope you don’t mind that I am asking a favor of you. My passport is enclosed. Could you take it to the Department of State and ask them to O.K. for a trip to Moscow to attend the conference there. I will also write a letter today to them and tell them that, since they have given me no other advice, I am applying to have my passport O.K’d for travel in Russia, and that you will bring it over. I am also writing the Soviet Ambassador, telling him I would like to go to the meeting, but that my passport has not yet been O.K’d for travel in Russia.

If the passport is O.K’d, could you get the visa from the Soviet Embassy and send it back to me.

I feel embarrassed in having to ask these favors of you, when I do not even know you personally. I am grateful to you for your help.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO A. N. NESMEYANOV, FEBRUARY 25, 1955

A February 16 letter from the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union informed Feynman that his expenses to and from Moscow would be paid.

Mr. A. N. Nesmeyanov

President

Academy of Sciences of U.S.S.R.

Moscow, Russia

Dear Mr. Nesmeyanov:

I should like to thank the Academy of Sciences for their kind invitation to attend the conference on Quantum Electrodynamics and Elementary Particles to be held March 31 to April 6. Their generosity in paying for all my traveling expenses makes it financially possible for me to come.

I shall accept the invitation, but there remains one uncertainty. My passport at present is not valid for travel in the USSR and I have applied to the U.S. Department of State for the necessary extension. If it is granted I shall surely come. I am embarrassed to have still to give you such an indefinite reply even after the long delay which I have made in replying to you. I thank you for your patience in this matter.

The invitation asked that I send you, at this time, the thesis of whatever communication I may wish to present. I assume that means a summary, rather than the complete paper. Unfortunately, I have not done much successful original work in the field which is not already published. I enclose a summary of work in a closely related problem. Perhaps you will decide that this is not suitable for the conference because the subject is somewhat afield. Please do not hesitate to tell me if this is the case. I am also preparing two other papers, assuming that one or the other will be of interest. One is on the present situation with regard to the accuracy of the comparison of quantum electrodynamics to experiments, and a discussion of the theoretical problems remaining to be solved to make this comparison more complete. Another is this:There was recently a conference at Rochester, N.Y. on high energy physics. I could give a summary of this conference, particularly the latest experiments of interest with mesons which have not yet been published.These things are not original work of course, and perhaps others intend to report on them. If there is any desire for it I could give a more general introductory survey talk on the present situation in theoretical physics of elementary particles. Or I could be more specific and describe some incomplete original work on the effects of closed loop diagrams in the pseudoscalar meson theory.

I would appreciate it if you could tell me which of these subjects would fit best into the plan of the conference so that I could concentrate my attention on preparing them.

I have done some work on the theory of liquid helium which may be of interest particularly to Professor Landau who has done so much work on this problem. I am looking forward to discussing it informally with Professor Landau. But if there is any opportunity, outside the conference, at which he would like me to give a more formal talk on this subject, I shall be glad to.

Thank you again for the kindness and generosity of your invitation. I hope I can come, but in any event, I am sure it will be a very successful conference.

Sincerely,

R. P. Feynman

K. D. NICHOLS TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, FEBRUARY 28, 1955

Dear Professor Feynman:

This is in reply to your letter dated January 14, 1955, which requested advice concerning the invitation received by you from the Russian Embassy to take part in the Conference which will be held by the Academy of Sciences in Moscow from March 31 to April 6, 1955.

In our review of foreign travel on the part of employees or former employees of the United States atomic energy program, it is our policy not to interfere with such travel, unless it is of such nature as to indicate an undue risk to security or involve the personal safety of the traveler.

Because of the highly classified information to which you have had access during your association with the atomic energy program, it is our view that your attendance at this Conference would constitute an unwarranted risk and it is strongly recommended that you decline the invitation.

Your interest in notifying the AEC of this matter is appreciated.

Sincerely yours,

K. D. Nichols

General Manager

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO A. N. NESMEYANOV, MARCH 14, 1955

Mr. A. N. Nesmeyanov

President,

Academy of Sciences of U.S.S.R.

Moscow, Russia

Dear Mr. Nesmeyanov:

In my last letter I accepted the invitation to the conference on Quantum Electrodynamics provided a passport would be granted by the State Department.This matter is still pending but in the meantime circumstances have arisen which make it impossible for me to attend. I hope that my vacillations have not caused you too great inconvenience.

I should again like to thank the Soviet Academy for their kindness and generosity in inviting me. I am sure that it will be a very successful conference, and wish you the best of luck with it.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO WALTER M. RUDOLPH, MARCH 14, 1955

Mr.Walter M. Rudolph

Assistant to the Science Adviser

Department of State

Washington, D.C.

Dear Sir:

Thank you for your letter of March 3, acknowledging mine of February 24.

Since I wrote you, K. D. Nichols, of the Atomic Energy Commission, has written to me recommending that I do not go, as such a trip would constitute an unwarranted risk in view of the fact that I had access to highly classified stuff during the war.

I have decided to take his advice.Therefore I withdraw my request that my passport be OK’d for travel in Russia. Mr. Wallace Atwood will pick it up.

As you know, I had already accepted the invitation pending the OK of the passport. I have now written to the Soviet Ambassador that the passport matter is still pending, but that circumstances have arisen which make it impossible for me to attend.This letter and others involved are enclosed.

Does it strike you that prompt replies to requests for their State Department’s views might make it easier for citizens to act in such a way as to protect the department from unnecessary embarrassment?

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

WALTER J. STOESSEL, JR., TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, MARCH 15, 1955

Dear Dr. Feynman:

I refer to the letter which you addressed to the Department on January 14, 1955 and to subsequent communications with the Science Advisor’s Office and the National Academy of Sciences concerning the invitation which you received to take part in the All-Union Conference on the Quantum Theory of Electrodynamics and the Theory of Elementary Particles to be held in Moscow, U.S.S.R., March 31 to April 6, 1955 under the sponsorship of the Academy of Sciences of the U.S.S.R. The long delay in reaching a Department position concerning your response to this invitation has been occasioned by the necessity of consulting with a number of interested offices and agencies including those which are aware of considerations stemming from your war-time experience in the field of atomic energy. It now appears that these considerations make it highly undesirable for you to visit the Soviet Union and, consequently, we urge that you decline the invitation.

It is too early to say whether a tendency on the part of the Soviet Government to encourage somewhat larger numbers of Western scientists to visit the Soviet Union and, conversely, to send a few more Soviet scientists abroad represents any basic change in the Soviet attitude toward the international exchange of scientific information. However, there are strong indications that the Soviet Government in so doing is primarily motivated by the prospect of propaganda gains in the international political field and has little intention of establishing more normal scientific relations which would involve greater exchange of mutually beneficial scientific information. In this connection, it might be noted that the presence of Western scientists at purely internal Soviet conferences and meetings is more susceptible to effective Soviet propaganda exploitation than contacts between Soviet and Western scientists at meetings or conferences of recognized international organizations or groups.

Sincerely yours,

Walter J. Stoessel, Jr.

Officer in Charge

USSR Affairs

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO MR. WALTER J. STOESSEL, JR., APRIL 4, 1955

Mr.Walter J. Stoessel, Jr.

Department of State

Washington, D.C.

Dear Mr. Stoessel:

Thank you for your letter of March 15. In view of a letter from K. D. Nichols, of the Atomic Energy Commission, voicing similar views to those in your letter, I have declined the invitation to attend the Soviet Conference of Quantum Electrodynamics.

Sincerely yours,

R. P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO RALPH BOWN, MARCH 7, 1958

A member of the “Advisory Board in Connection with Programs on Science” wrote Feynman to discuss the formalities of a pending working relationship. Feynman had agreed to be an advisor for a television program that Warner Brothers was producing for the Bell System Series. Among other formal legal stipulations, the letter stated that “it is provided that for each program an individual be named ‘the designee’ from whom Warner may accept authoritative comment, advice and recommendations in the name of the Scientific Advisory Board.”

Mr. Ralph Bown

Advisory Board in Connection with Programs on Science

New York, New York

Dear Mr. Bown:

Thank you for your formidable letter describing the legal interrelations. Who is the “designee”? Is that me or am I an advisor, or what the hell? Put it in plain clear one-syllable words, please.

Anyway the Warner guys have an author named Marcus. He has come to my office on two occasions each for about half a day (so you owe me one day’s pay more).The purpose was to get more complete detailed explanation of some of the scientific matters in the report I wrote (like simultaneity in relativity, how short times are measured, etc., etc.). He is very intelligent and I was successful in explaining a great deal to him.

Although the gimmicks, etc. were not on the agenda, he told me about them, and left a document describing his plans. I made no comment on these ideas, telling him they are not my business.

(On the other hand, my hair stood on end as I read the “ideas” for presenting the material. But I kept my hat on and it wasn’t noticed. It will relieve me a little if I can say a word to somebody so I can let out steam. So please don’t consider the following as a valid or official opinion. It is just me letting off unofficial views and is to be kept safely within these parentheses).

(The idea that the movie people know how to present this stuff, because they are entertainment-wise and the scientists aren’t is wrong.They have no experience in explaining ideas, witness all movies, and I do. I am a successful lecturer in physics for popular audiences. The real entertainment gimmick is the excitement, drama and mystery of the subject matter. People love to learn something, they are “entertained” enormously by being allowed to understand a little bit of something they never understood before. One must have faith in the subject and in people’s interest in it. Otherwise just use a Western to sell telephones! The faith in the value of the subject matter must be sincere and show through clearly. All gimmicks, etc. should be subservient to this. They should help in explaining and describing the subject, and not in entertaining. Entertainment will be an automatic byproduct.)

Don’t worry, I’m keeping my hat on and will limit myself to scientific advice only.

Sincerely,

R. P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO MIMI PHILLIPS, JUNE 1958

Feynman’s influential work on liquid helium started in 1953, and it continued to occupy him (and his collaborator Mike Cohen) over the next five years. This letter was written to the young daughter of his cousin in June 1958 while on the way to the Conference on Low Temperature Physics, in Leiden, the Netherlands. It was later published in the Phillips’s local newspaper.

Flying Over England

Dear Mimi:

Am I not terrible—not answering your two letters and cards! You write very good letters—and you are right that I should answer them and write to my Mom—after I finish this one I will write to Mom.

I am on my way to Europe and am flying over England. I am going to land in Holland, in Amsterdam. I have to give a talk at a conference. It is about how liquefied helium behaves.

It is a very strange liquid indeed—it can flow coasting through even the finest cracks without you having to push it.You know how water will very slowly seep through a piece of cloth, or dirt, say? Well, liquid helium flows right through very easily.

It has other crazy properties and physicists have been trying a long time to understand all about it, by doing lots of experiments and lots of thinking. The biggest thinking step forward was by a man named Landau in Russia in 1941 (and the second big thinking step was by me, and now we understand it pretty well). So he was to be honored by giving the first big lecture at this conference (which is about all kinds of strange things that happen at very low temperatures).

But he can’t come (we all suspect it is because the Russians won’t trust him to leave the country, maybe he would run away). So I have to do it. It is day after tomorrow and I haven’t figured out what to say yet! They just told me I would have to do it.

After that I go to another conference in Geneva, Switzerland. This is about all the strange new particles we get when we hit two atoms together very, very hard (it is called a conference on high energy physics).

Atoms are complicated, maybe like watches are—but they are so small, that all we can do is smash them together and see all the funny pieces (gears, wheels and springs) which fly out. Then we have to guess how the watch is put together. In the last few years we’ve been having enough trouble trying to distinguish one gear wheel from another and to count them. Now it looks like we know most of the parts that go in—but nobody knows how they fit together.

How long will it take for us to figure that out? Five years, ten years? Will I be able to help?—I’ll try. I’ll have to think very hard and imagine all kinds of possibilities. Why do you think we want to bother to figure out what atoms are made of and how they are put together?

When I come back I am not going out West right away, but I’ll stay in Ithaca, N.Y., at Cornell University until Christmas. Maybe I’ll see you then. Thank you very much for writing.Why didn’t I answer sooner? Because I am bad, bad. Most people are bad, you know, in one way or another—but they are not always bad, and they have other good points to compensate. So if you think I’m bad for not writing—see, I’m not always bad—today I’m good—and I have some compensations because I remember we had a very, very good time together in Connecticut.

Best of luck and regards to your Mom and Pop.

Dick Feynman

P.S. How goes the piano lessons?

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO BILL WHITLEY, MAY 14, 1959

Mr. Bill Whitley

Public Affairs KNXT

Hollywood, California

Dear Mr.Whitley:

On May first you recorded an interview of me by Bill Stout for expected use on your program, “Viewpoint,” for May 10.

10 The tape was not used, and you have asked me to record another interview. No very clear reason was given for this request. It was said at one time that my views might antagonize people, at another time that the fault was entirely with Mr. Stout (that by his questions he intimated too strongly that he agreed with me).

Yesterday I heard an audio tape recording of the interview. I found that I had ample opportunity to express my views, that these views were expressed honestly and sincerely and in a calm logical and undogmatic manner. I cannot conceive that antagonism could result from the way I expressed myself, but only perhaps from the fact that I did express myself. It is clearly stated that my views are my own personal opinion, and that not all scientists agree.The viewpoints expressed, or others very close to them, are held by a very large number, albeit perhaps a minority, of very intelligent people in this country.There is no reason why they should not find some expression on our public communication channels such as television.

Mr. Stout conducted the interview with very considerable skill. The questions were clear and unambiguous and so designed to permit me to develop and express my ideas in the clearest way possible. His remarks were solely in the form of questions; neutral questions which in no way implied agreement or disagreement with the ideas I was developing.

The television industry can be proud to be part of the tradition of freedom of expression of this country. And the program bearing the proud name “Viewpoint” makes an important contribution in discussing the controversial issues of our time. Nevertheless, I consider your refusal to utilize the program recorded with me as a direct censorship of the expression of my views.

I see no reason to make a new recording. I will not change my views, and I would not want to change my manner of expressing them.

If you are still concerned about the position of Mr. Stout, please feel free to make, or have him make, an announcement to the effect that the station, or he, does not agree with my views.

In view of these considerations, could I ask you to please reconsider your decision?

Awaiting an early reply, I am

Yours sincerely,

R. P. Feynman

Feynman did not give another interview, and the station ran the program. However, the program was shown earlier in the day than its advertised time, thus guaranteeing a much smaller audience.

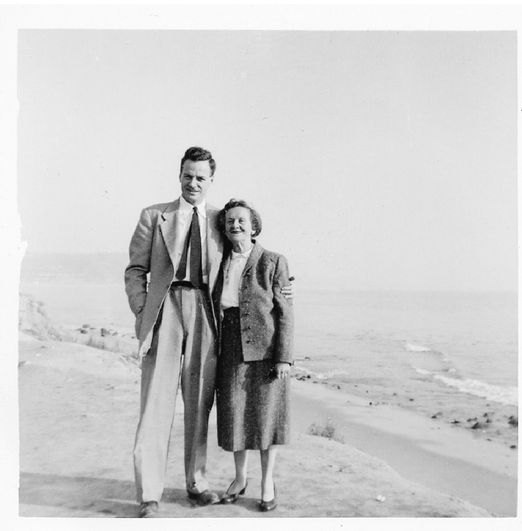

Richard and Gweneth, 1959.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO GWENETH HOWARTH, MAY 29, 1959

Dear Gweneth,

Well, at last!

I was overjoyed to hear that you are coming at last.We’ve been waiting so long! What did you finally do to the embassy to wake them up? I need you more than ever—I’m getting sick of my own meals—all I can cook is steak, lamb chops, and pork chops with peas, corn or lima beans and there is not much variety in that. I’m looking forward to being much happier—and now in 3 weeks I’ll be calling for you at the airport!

But please write right away anything you know about the flight, like TWA flight number, or exact time of arrival in Los Angeles—or exact time it leaves N.Y. (you said arrives at Los Angeles at 11 AM—but TWA says they have none that do—only flight 5 leaving N.Y. at 9:30 AM, arriving Los Angeles 11:35 AM. Is that the one?) The more details I have the better I can check upon things if something seems to be mixed up. Also give me the time of arrival of the Stadenhaus and whether and where you stay over night in N.Y. or what. I have to take care of you too, you know. As soon as you arrive here you are a responsibility of mine to see you are happy and not scared—so I’d like to know where you are supposed to be to call you to see if everything is all right. In case of any trouble at all please call me—put in 10¢ and tell the operator you want to make a collect call station to station to Los Angeles, SYCAMORE 7-XXXX. If I don’t answer try the school where I work—this time tell the operator you want to make a collect call person-to-person to Richard Feynman, telephone number SYCAMORE 5-XXXX. If you can’t get me and are positively desperate, try calling collect to Matthew Sands—person-to-person—same number SY-5-XXXX. I’ll tell him you may call, and you can tell him your troubles and he will straighten it all out. By the way, he is glad to hear you are coming at last, because I promised he and his wife they would be the first dinner guest after you come. He says he wants pheasant! What should we give him?

Anyway, don’t be too scared—America is a good place and the people all speak English—after a fashion—so just ask what you want to know.

If you came 2 weeks earlier I’d sure have a lot for you to do—I’m going to be on television, in an interview with a news commentator on June 7th and there may be a lot of letters to answer.

Leave your ski things there.We do have skiing here in the mountains 60 min. away, but I have never skied—so save the weight. We may go once or twice if you want to try to teach me how—but we can borrow (or rent) things from friends for the few times, if ever, we go. They are too heavy to bring along just for that.

The weather is hot in summer—warm in winter—I have never seen it freeze. Usually 60°-65° or so. Cold nights. A heavy coat is not necessary. I never wear a coat at all except on coldish rainy days (very few) when I wear a rain-coat. But a light coat will come in very handy.

I went to buy tires for your car—but they are very expensive and I’ll have to shop around—so I decided to wait and let you do the shopping around until you find a reasonable price—there is no sense in putting fancy expensive tires on an old car. Don’t worry about the driver’s license—we can get that here. Anyway you’ll need a lesson or two on the right side to get familiar with our streets and the car.

It is the season for the beach here too—but I haven’t gone yet. Last week I went on a camping trip with friends into the desert for 2 nights. It’s fun.

O.K. I’m managing poorly without you. Come quick.

Yours,

Richard