1960-1965

After flirting with the idea for a long time, Feynman spent a summer, and then a sabbatical year, doing research in the area of molecular biology at Caltech. While working with Bob Edgar and others on viruses that attacked bacteria, he discovered several cases of “back mutations” that occurred close together—perhaps giving a clue to the sequence of DNA. Edgar urged him to publish his findings, and at the invitation of James Watson, Feynman later gave a talk on the subject to the biology department of Harvard University. He then returned to his first love, physics.

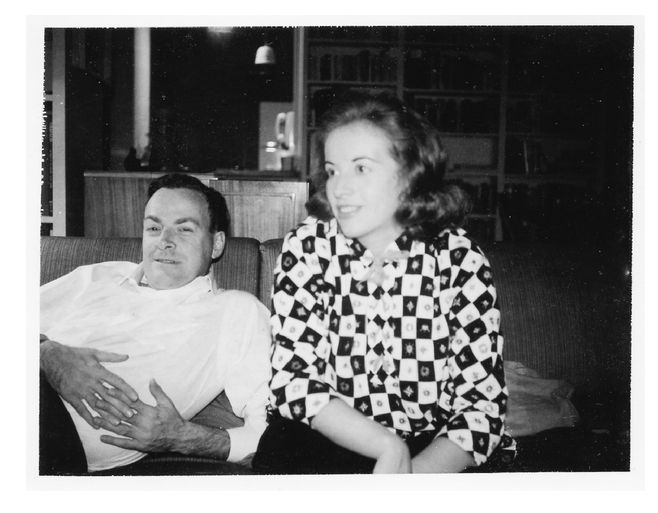

Gweneth became his wife on September 24, 1960. He soon began to boast of his newfound domesticity, and perhaps it provided a buffer from the demands of his growing renown.

He was increasingly turning his attention to popularizing physics, and in 1961 he worked as the scientific advisor for the film “About Time,” which NBC aired on prime-time television. Part of the Bell System Science Series, the hour-long program brought Feynman’s name and personality to an audience far beyond his colleagues and fellow scientists.The letters from perfect strangers—students, laymen, and the occasional fan—soon followed.

My brother, Carl, was born in 1962, the day before the presentation to Feynman of the E. O. Lawrence Award, a prize given by the Department of Energy for contributions in the field of atomic energy.The local newspaper ran a picture of Richard and Gweneth at the hospital, he holding his medal and she holding infant Carl.

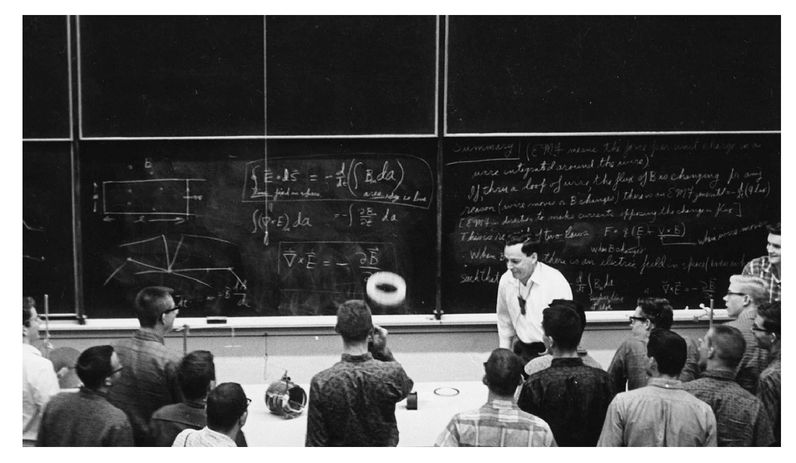

More significantly for his reputation as a teacher, this same period saw the birth of The Feynman Lectures on Physics. Based upon a series of freshman and sophomore lectures given at Caltech, and edited by Robert B. Leighton and Matthew Sands, the books have become a unique and timeless portrait of physics—a work of art, in the eyes of many. During the 1962-1963 academic year, Feynman also gave his now-legendary Lectures on Gravitation. Soon thereafter Feynman’s lectures on more advanced topics were also published. A 1963 letter to a colleague at Cornell discusses another burgeoning enterprise: Feynman lectures on film.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO WILLIAM H. MCLELLAN, NOVEMBER 15, 1960

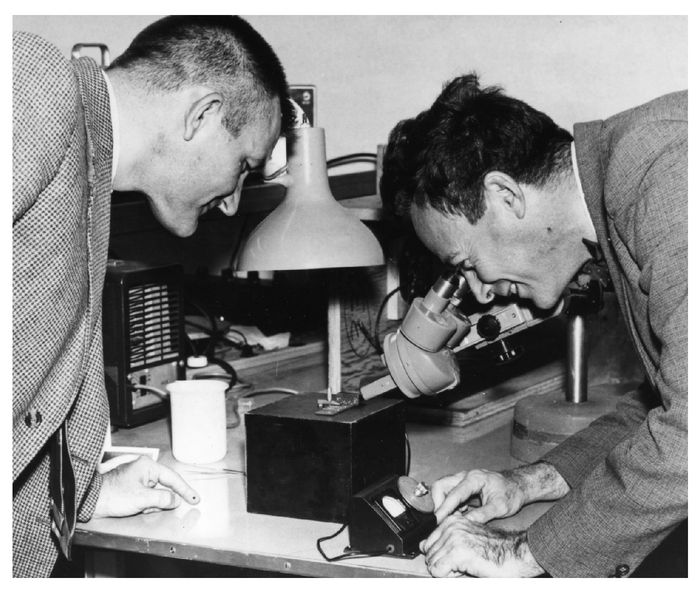

In 1959 Feynman realized that it should be possible to reduce the physical size of stored words, even machines, to a scale of a few tens or hundreds of atoms in each dimension—that is, he envisioned a new field of science now called nanotechnology

. In a famous lecture titled, “There Is Plenty of Room at the Bottom,”11 he expounded this view and promoted it among scientists and engineers by offering prizes of $1,000 each for two challenges: (1) to “take the information on the page of a book and put it on an area 1/25,000 smaller in linear scale in such a manner that it can be read by an electron microscope”; and (2) to build “a rotating electric motor which can be controlled from the outside and, not counting the lead-in wires, is only 1/64 inch cube.” The motor challenge was met almost immediately, but it was achieved with craftsmanship only—no new technology was needed, which is what he had hoped to encourage.

Mr.William H. McLellan

Electro-Optical Systems, Inc.

Pasadena, California

Dear Mr. McLellan:

I can’t get my mind off the fascinating motor you showed me Saturday. How could it be made so small?

Before you showed it to me I told you I hadn’t formally set up that prize I mentioned in my Engineering and Science article.The reason I delayed was to try to formulate it to avoid legal arguments (such as showing a pulsing mercury drop controlled by magnetic fields outside and calling it a motor), to try to find some organization that would act as judges for me, to straighten out any tax questions, etc. But I kept putting it off and never did get around to it.

Feynman and William McLellan with micromotor, 1960.

But what you showed me was exactly what I had had in mind when I wrote the article, and you are the first to show me anything like it. So, I would like to give you the enclosed prize.You certainly deserve it.

I am only slightly disappointed that no major new technique needed to be developed to make the motor. I was sure I had it small enough that you couldn’t do it directly, but you did. Congratulations!

Now don’t start writing small.

I don’t intend to make good on the other one. Since writing the article I’ve gotten married and bought a house!

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO RONNIE KERNAGHAN, FEBRUARY 20, 1961

An eighth-grader writing a job survey needed some information about the life of a theoretical physicist—the courses needed to become one, as well as the potential job opportunities, working conditions, and pay rates.

Mr. Ronnie Kernaghan

Paso Robles, California

Dear Mr. Kernaghan:

I am sorry but I have no information on any of the questions you asked me.

If you asked me is it an adventuresome and exciting life trying to find out about how nature works, I could answer that. It is, and it is a lot of fun. But make sure you have talent for it.

Sincerely,

R. P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO EARL UBELL, FEBRUARY 21, 1961

Mr. Earl Ubell

New York Herald Tribune

New York, New York

Dear Earl:

A Miss Draper from your paper kindly sent me a copy of your article “Gravity, the Disrespectful.”

12 Very good, I thought, as I read it. Usually science reporting is no damn good at all. But the last line—ah, there is a man that understands, and says it better than I can!

I have a vague recollection of being short or impatient with you somewhere in the past. At least that is how I have become toward the newspaper science press generally. I apologize; to you, but not to the others.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO FLOYD GOLD, APRIL 5, 1961

A letter from an old friend, Floyd Gold, dated March 25, 1961, expressed concern about his son’s future education. “He is fifteen years of age. . . and is at present constructing a digital computer as his entry in the Westinghouse Science Talent competition.” Gold went on to say that his son was completely self-taught except for a seven-week course in the field of computer logics. The assistant principal of Far Rockaway High School (Feynman’s alma mater) suggested that Gold write Feynman and ask for a list of courses and schools to which his son might aspire. Mr. Gold was also curious about Feynman’s feelings on engineering versus a pure science approach to his son’s education.

Mr. Floyd O. Gold

Far Rockaway, New York

Dear Floyd:

It is very exciting to hear from someone from the old days whose name I remember. I married Arline Greenbaum from Cedarhurst. She died in 1946 and I am now beginning my third marriage, to an English girl. No kids yet, but I hope to soon.

My advice to your son is this. It is very lucky he is interested in something and gets delight out of doing something. He should be encouraged to do exactly as he wants—I don’t mean in the future—I mean day to day, without some grand plan. At his stage, engineering and physics education is nearly the same, and will be for several years. Many is the man who has changed from one to the other even after graduating from college (but not as late as after graduate college) without any great difficulty.

So let him play with computers and ideas as hard as he can. His math background will develop as he needs it to understand his circuits, etc. He must have freedom to pursue his delight now, and when he becomes a great expert in something, he will find it easy to pick up other related subjects.

If, on the other hand (contrary to what your letter implies), he is average at everything and gets no “charge” out of doing anything in particular (or gets plenty of “charge” out of everything, but goes from one thing to another) then I don’t know what to advise.

Sincerely,

R. P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO FREDERICH HIPP, APRIL 5, 1961

Frederich Hipp, a high school student, was fascinated by physics (“atomic theory and quantum mechanics in particular”) and had built a cloud chamber for his science project. He was concerned, however, that he had little aptitude for math. His question to Feynman: “Can a person of normal mathematical ability master enough math to do work on some professional level in this field?”

Mr. Frederich Hipp

New Milford, Connecticut

Dear Sir:

To do any important work in physics a very good mathematical ability and aptitude are required. Some work in applications can be done without this, but it will not be very inspired.

If you must satisfy your “personal curiosity concerning the mysteries of nature” what will happen if these mysteries turn out to be laws expressed in mathematical terms (as they do turn out to be)?You cannot understand the physical world in any deep or satisfying way without using mathematical reasoning with facility.

How do you know you don’t have an aptitude for math? Perhaps you disliked your teacher, or it was presented wrong for your type of mind.

What do I advise? Forget it all. Don’t be afraid. Do what you get the greatest pleasure from. Is it to build a cloud chamber? Then go on doing things like that. Develop your talents wherever they may lead. Damn the torpedoes—full speed ahead!

What about the math? Maybe (1) you might find it interesting later when you need it to design a new apparatus, or (2) you may not go on with your present ambition to understand everything, but instead find yourself a leader in some other direction, such as building the most ingenious rocket-ship control devices, or (3) biological problems may ultimately absorb all your interest and talent for doing experiments and learning about nature, etc.

If you have any talent, or any occupation that delights you, do it, and do it to the hilt. Don’t ask why, or what difficulties you may get into.

If you are an average student in everything and no intellectual pursuit gives you real delight, then I don’t know how to advise you.You will have to discuss it with someone else. It is a problem that I have not thought about very hard.

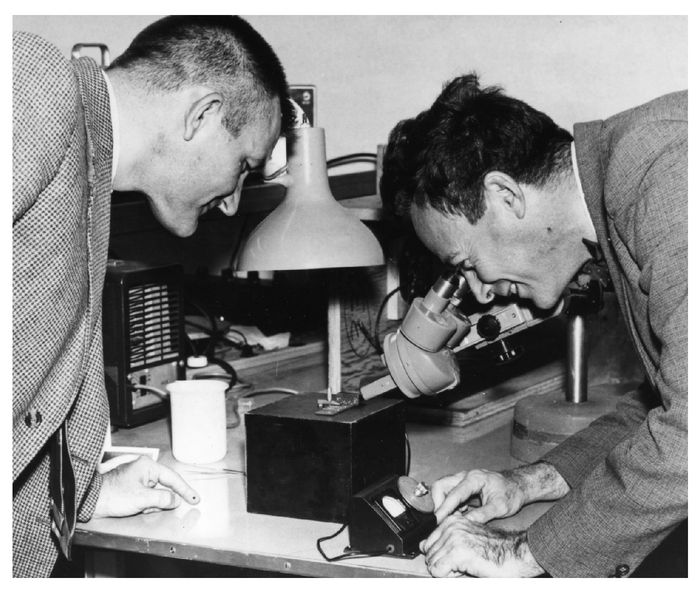

The Feynman Lectures on Physics, 1962.

Sincerely,

R. P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO HELEN CHOAT, JULY 26, 1961

The “About Time” film was by this time over two years in the making.Warner Brothers produced the footage, and N. W. Ayer and Son was chosen to publish the accompanying materials and workbooks.

Miss Helen Choat

N.W. Ayer and Son

Rockefeller Center

New York, New York

Dear Miss Choat:

You asked me to review the “Biographical Material” about me.The second sentence of the first paragraph is wrong. It should read something like “He started work in connection with the atomic bomb at Princeton in 1941 and continued with the project until its successful conclusion at Los Alamos in 1945.” I didn’t work with Einstein, Einstein didn’t work on the atomic bomb, and Einstein is not the father of the atomic bomb.

Finally, please omit the reference to the National Academy of Sciences. Also I am not sure if I am a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science—I don’t remember.

You also wanted in a few lines how I became attracted to science: “My father, a business man, had a great interest in science. He told me fascinating things about the stars, numbers, electricity, etc. Wherever we went there were always new wonders to hear about; the mountains, the forests, the sea. Before I could talk he was already interesting me in mathematical designs made with blocks. So I have always been a scientist. I have always enjoyed it, and thank him for this great gift to me.”

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO GWENETH FEYNMAN, OCTOBER 11, 1961

The following letter was written from the Solvay Conference in Brussels. Gweneth was pregnant with Carl at the time.

October 11, 1961

Hotel Amigo, Brussels

Hello, my sweetheart,

Murray and I kept each other awake arguing until we could stand it no longer.We woke up over Greenland which was even better than last time because we went right over part of it. In London we met other physicists and came to Brussels together. One of them was worried—in his guidebook the Hotel Amigo was not even mentioned. Another had a newer guide—five stars! and rumored to be the best hotel in Europe!

It is very nice indeed.All the furniture is dark red polished wood, in perfect condition; the bathroom is grand, etc. It is really too bad you didn’t come to this conference instead of the other one.

At the meeting next day things started slowly. I was to talk in the afternoon. That is what I did, but I didn’t really have enough time for we had to stop at 4 pm because of a reception scheduled for that night. I think my talk was OK tho—what I left out was in the written version anyway.

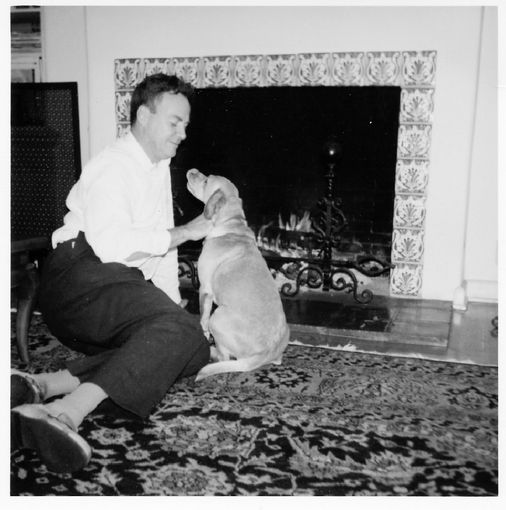

Richard and Gweneth, 1961.

So that evening we went to the palace to meet the king and queen.Taxis waited for us at the hotel—long black ones—and off we went at 5 pm, arriving through the palace gates with a guard on each side, and driving under an arch where men in red coats and white stockings with a black band and gold tassel under each knee opened the doors. More guards at the entrance, in the hallway, along the stairs, and up into a ballroom, sort of. These guards stand very straight, dark grey Russian-type hats with a chin strap, dark coats, white pants, and shiny black leather boots, each holding a sword straight up.

In the “ballroom” we had to wait perhaps 20 minutes. It has inlaid parquet floors, and L in each square (Leopold—the present king’s name is Baudoin, or something).The gilded walls are 18th century and on the ceiling are pictures of naked women riding chariots among the clouds or something. Lots of mirrors and gilded chairs with red cushions around the outside edge of the room—just like so many of the palaces we have seen, but this time it was alive, no museum, everything clean and shining and in perfect condition. Several palace officials were milling around among us. One had a list and told me where to stand but I didn’t do it right and was out of place later.

The doors at the end of the hall open—guards are there, and the king and queen so we all enter slowly and are introduced one by one to the king and queen.The king has a young semi-dopey face and a strong handshake, the queen is very pretty. (I think her name is Fabriola—a Spanish countess she was.) We exit into another room on the left where there are lots of chairs arranged like in a theatre, with two in front, also facing forward, for K & Q later, and a table at the front with six seats is for illustrious scientists (Niels Bohr, J. Perrin (a Frenchman), J. R. Oppenheimer etc.).

It turns out the king wants to know what we are doing, so the old boys give a set of six dull lectures—all very solemn—no jokes. I had great difficulty sitting in my seat because I had a very stiff and uncomfortable back from sleeping on the plane.

That done, the K & Q pass thru the room where we met them and into a room on right (marked R). All these rooms are very big, gilded,Victorian, fancy, etc. In R are many kinds of uniforms, guards at door, red coats, white coat sort of waiters to serve drinks and hors d’oeuvres, military khaki and medals, black coat—undertaker’s type (palace officials).

On the way out of L into R, I am last because I walk slowly from stiff back and find myself talking to a palace official—nice man—teaches math part time at Louvain University, but his main job is secretary to the queen. He had also tutored K when K was young and has been in palace work 23 years.At least I have somebody to talk to, some others are talking to K or to Q; everybody standing up. After a while the professor who is head of conference (Prof. Bragg) grabs me and says K wants to talk to me. I pull boner #1 by wanting to shake hands again when Bragg says, “K, this is Feynman”; apparently wrong—no hand reaches up, but after an embarrassed pause K saves day by shaking my hand. K makes polite remarks on how smart we all must be and how hard it must be to think. I answer, making jokes (having been instructed to do so by Bragg, but what does he know?)—apparently error #2. Anyway, strain is relieved when Bragg brings over some other professor—Heisenberg, I think. K forgets F and F slinks off to resume conversation with Sec’y of Q.

After considerable time—several orange juices and many very very good hors d’oeuvres later—a military uniform with medals comes over to me and says, “Talk to the queen!” Nothing I should like to do better (pretty girl, but don’t worry, she’s married). F arrives at scene: Q is sitting at table surrounded by three other occupied chairs—no room for F.There are several low coughs, slight confusion, etc. and lo! one of the chairs has been reluctantly vacated. Other two chairs contain one lady and one Priest in Full Regalia (who is also a physicist) named LeMaître.

We have quite a conversation (I listen, but hear no low coughs, and am not evacuated from seat) for perhaps 15 minutes. Sample:

Q:“It must be very hard work thinking about those difficult problems.”

F: “No, we all do it for the fun of it.”

Q: “It must be hard to learn to change all your ideas” (a thing she got from the six lectures).

F: “No, all those guys who gave you those lectures are old fogeys—all that stuff was in 1926, when I was only eight, so when I learned physics I only had to learn the new ideas. Big problem now is, will we have to change them again?”

Q:“You must feel good, working for peace like that.”

F: “No, never enters my head, whether it is for peace or otherwise we don’t know.”

Q: “Things certainly change fast—many things have changed in the last hundred years.”

F: “

” (I thought it, but controlled myself.)

F: “Yes,” and then launched into lecture on what was known in 1861 and what we found out since—adding at end, laughingly, “Can’t help giving a lecture, I guess—I’m a professor, you see. Ha, ha.”

Q in desperation, turns to lady on her other side and begins pleasant conversation with same.

After a few moments K comes over, whispers something to Q who stands up and they quietly go out. F returns to Sec’y of Q who personally escorts him out of palace past guards, etc.

I’m so terribly sorry you missed it. I don’t know when we’ll find another king for you to meet.

I was paged in the hotel this morning just before leaving with the others.

Phone call—I returned to the others and announced, “Gentlemen, that call was from the queen’s secretary.” All are awestruck, for it did not go unnoticed that F talked longer and harder to Q than seemed proper. I did-n’t tell them, however, that it was about a meeting we arranged—he was inviting me to his home to meet his wife and two (of four) of his daughters, and see his house. I had invited him to visit us in Pasadena when he came to America and this was his response.

His wife and daughters are very nice and his house was positively beautiful. You would have enjoyed that even more than visiting the palace. He planned and built his house in a Belgian style, somewhat after an old farm-house style, but done just right. He has many old cabinets and tables inside, right beside newer stuff, very well combined. It is much easier for them to find antiques in Belgium than for you in Los Angeles as there are so many old farms, etc. He has large grounds and a vegetable garden—and a dog—from Washington—somebody gave the king and the K gave to him. The dog has a personality somewhat like Kiwi because I think he is equally loved.

13 He even has a bench in his garden hidden under trees that he made for himself to go and sit on and look at the surrounding countryside.The house is slightly bigger than ours and the grounds are much bigger but not yet landscaped.

Richard and Kiwi, or “Snork,” 1961.

I told him I had a queen in a little castle in Pasadena I would like him to see—and he said he hoped he would be able to come to America and see us. He would come if the Q ever visits America again.

I am enclosing a picture of his house, and his card so I don’t lose it.

I know you must feel terrible being left out this time—but I’ll make it up someday somehow. Don’t forget I love you very much and am proud of my family that is and my family that is to be. The secretary and his wife send their best wishes to you and our future.

I wish you were here, or next best thing, that I were there. Kiss SNORK and tell Mom all my adventures and I will be home sooner than you think.

Your husband loves you.

Your husband.

Gweneth herself would plan a number of adventures over the years. Trips to areas as remote as the tribal lands of the Tarahumara Indians in Mexico, and many camping trips to the middle of nowhere, were the family norm.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO VOLTA TORREY, NOVEMBER 15, 1961

Feynman gave a talk titled “The Future of Physics” at the MIT Centennial Convocation in April 1961. The centennial authorities considered publishing a book of the speeches made that day, but the project was eventually dropped. The Technology Review had a high opinion of Feynman’s talk and wanted to publish it. Mr. Torrey wrote Feynman to obtain permission and enclosed the proposed manuscript.

Mr.Volta Torrey, Editor

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Dear Editor Torrey:

There is some confusion about the manuscript of my talk at the MIT Centennial. First I gave the talk and a tape recording was made (call it Version A). Then somebody related to the Centennial book sent me a highly edited and rewritten version (call it Version B) which is similar to your story and is the manuscript they gave you which you sent me. But I didn’t like version B and sent back asking for the original tape, (Version A), which I corrected and returned as Version C.

14Try to get Version C from the book boys. I like it much better than version B which you want to print. Wouldn’t you rather print version C? I have no copy of C or I wouldn’t give you the run-around.

Thanks for your patience.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO ALLADI RAMAKRISHNAN, JANUARY 30, 1962

The following letter is in response to a request to publish some unpublished work on a model of strong interactions. Mr. Ramakrishnan had already received permission to include some of Feynman’s notes on electrodynamics in a book, and he hoped to include the unpublished work as well. He wrote, “If you do not mind its inclusion, I will send it on to the press; otherwise I have to delete it and this may cause considerable confusion at this stage for the printers.” Mr. Ramakrishnan also offered to include any comments as a footnote.

Mr. Alladi Ramakrishnan, Director

The Institute of Mathematical Sciences

Madras, India

Dear Mr. Ramakrishnan:

I was sorry to see that you wanted to publish the model of strong interactions I once wrote about.The cover page of this work was marked “Publication of this work is not planned at present.” I didn’t publish it for a reason. I wasn’t sure that it was right (I mean, that Nature was really being described correctly). Now I am even less sure. Almost certainly it is wrong.

It is my policy to try to keep up the standard of my own published work—at least so that each article should have some relevance to Nature and her laws. Speculations about how it might come out are not satisfactory unless I feel that with high probability the speculation is in fact correct (unless I am writing a review article on present-day speculations, etc.).

So you embarrass me by taking seriously something that I think is not true. I would prefer that you leave it out.

However, since this might cause considerable confusion for the printers, as a second choice add to what you have, the following footnote:

“Professor Feynman feels that the physicists’ problem is not just to make speculative models, but to really find out what is going on in nature. Since, in his opinion, this model is a speculation and almost certainly does not describe the observed reality, he does not think it of sufficient value to warrant publication.”

Then you can, if you wish, go on to say something like “Nevertheless, the author thought that this model would be of sufficient interest to his readers as an example of the kind of thing being tried that he has included it here” or some such thing. Whatever you want. But if you do publish it, please add at least the paragraph preceding this one.

Sincerely,

R. P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO MR. Y, FEBRUARY 8, 1962

The television program “About Time” finally aired on the NBC network on February 5, 1962. A viewer whom I shall call Mr.Y, and who had complained previously to KRCA in Los Angeles about its presentation of the “orthodox” viewpoint on relativity, wrote the station to complain once again.15 He copied his letter to Feynman and four other scientists plus three organizations. In the letter, Mr.Y attacked the film’s presentation of the twin paradox

, charging that it was “propaganda” aimed at propagating incorrect orthodoxy, and asserted that his own correct viewpoint was being suppressed.

Dear Mr. Y:

You sent me a copy of a letter to KRCA about the program “Time.” I was scientific adviser to that program and am responsible for the inclusion of the traveling twin story. I included it because I believe it is correct. Please be assured that I am not interested in propaganda or persuading people.We agree that we should be interested only in what is right in science.

But if we are interested only in what is right, must we not conclude that the phenomenon suggested by the traveling twin is right? I honestly thought so, and I believed that the observed long lifetime of moving mu mesons confirmed it.You seem to think otherwise. I should be glad to learn of my error, if, indeed, it is an error. I have used these ideas in an essential way in my work in physics for many years and know of no direct violation of them—in fact, they seem to be very successful in predicting new phenomena. I would be surprised, but very pleased, to learn that there is another point of view which successfully does two things:

(1) Predicts correctly all those effects which have been carefully observed experimentally so far;

(2) Predicts a different result for the traveling twin.

Sincerely yours,

R. P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO MR. Y, MARCH 14, 1962

Mr. Y replied with several successive, emotional letters that attacked Feynman for joining with the science establishment in suppressing Mr. Y’s views but never explained clearly what those views were.

Dear Mr. Y:

I have received a number of letters from you which I do not understand. As you say, the question is not so much a matter of philosophy but of what phenomena occur. In order therefore to see if we really disagree on the phenomena associated with the clock paradox, I should like to ask what, in your opinion, would be the result of the following experiment:

A weak beam of negative µ-mesons of velocity v coming from a source pass through a thin counter B so the time of arrival of each can be noted. Half of them impinge on a piece of matter, A, thick enough to stop them, and in such circumstances that their subsequent decay can be detected.The mean time between entrance at B and decay in A (minus the small bit of time estimated to get from B to A, which can be made very small indeed) is measured. Let us call this τo (as you know, it comes out to be 2.2 x 10-6 seconds). In particular the probability/sec. of a meson in A to decay at time t is

In addition, those that miss A go around in a magnetic field through an angle close to 360° to a counter C. (Since C cannot be put exactly at 360° imagine a small correction is made to the data for the small time needed to go from C to the true 360° point.) How many counts do you expect will arrive at C? Supposing that the radius of the orbit is R, so the time to go around the circle is T = 2πR/v.

I presume your answer is one of two. Either (a) the lifetime to decay does not depend on the speed so the number in C is the same as in A after the same delay, namely

Or (b) the lifetime of a moving meson appears longer in the sense that the number arriving at C is

where τ is not τ0, the value of rest, but rather

where v is the velocity of the mesons going around the circle, and C is the speed of light. Or perhaps you expect a result different than either (a) or (b).

I was not able to tell by your letters what you would expect under these circumstances. Could you let me know, so we can discuss the matter further.

Will you accept my apologies for not answering your letters sooner. I am busy with several matters and do not take care of all my letters right away.

Sincerely,

R. P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO MR. Y, APRIL 3, 1962

Mr. Y, obviously pleased by Feynman having responded a second time and in such detail, sent a polite response that did not address the issue Feynman had raised. Feynman wrote back.

Dear Mr. Y:

My letter of March 14 was only to see whether we agree or disagree on what we would expect to happen in a given experimental situation. Of course, v is less than c and need not approach c. (For example, v might be ⅘) c).What would you expect to happen?

If I don’t know what your opinion is in this matter I don’t see much use to our writing letters back and forth because I don’t know whether my views disagree with yours or not.You speak of our “opposite viewpoints” and “my arguments” but I still don’t know whether we have opposite viewpoints or any argument on the results of this experiment. In short, I don’t know what your viewpoint is.

Therefore I hope to hear your opinion clearly and simply stated in your next letter. If you have any questions about the conditions of the experiment I shall be glad to explain them more fully.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO MR. Y, APRIL 10, 1962

Mr. Y responded by questioning the premises of Feynman’s thought experiment when the meson speed gets extremely close to the speed of light, and he raised a number of other qualitative objections to the theory of relativity. Feynman tried once more.

Dear Mr. Y:

Thank you for your letter of April 7. After reading it I still don’t know what you would expect to happen in the experiment in question.The purpose of scientific thought is to predict what will happen in given experimental circumstances. All the philosophical discussion is an evasion of the point. The mesons do not go at the speed of light. To be specific, take the case of mesons of such momentum that the radius of curvature in a field of 10,000 gauss is 44 cm. (corresponding, in the usual method of calculation, to velocity equal to 0.8 of the velocity of light). Suppose the counter C is placed 10 cm. in front of the 360° point—there is surely plenty of room for that. My question is now specific:“The field is 10,000 gauss, the mesons are selected (by a previous magnet and slits) to have a radius of curvature of 44 cm. The counter C is 10 cm. in front of the 360° point. What will be the relation of the number of counts in A and in C?”

This is not an artificial and arbitrary question meant to trap you. It is designed to see if we differ in our predictive understanding of Nature.We obviously differ in our way of analyzing and thinking, but the real question is whether we differ in our expectations of what will happen in given circumstances. If we do not, then there is no scientific question involved, it is only a matter of philosophic argument, and I would not be able to make a choice of who is right. If we do differ in our expectation then it is very easy to decide who is right.We do the experiment and see.

Please, [Mr.Y.], answer the question. Don’t go on telling me I ignore relativity in “my thesis,” or speaking of “my philosophy” or that I ignore the fact that a meson is a particle, etc., etc.All that may or may not be true.Are you trying to tell me I can’t set up the counters in the arrangement indicated or that a magnetic field of approximately 10,000 gauss cannot be made, or that there are no mu mesons? If not, and you agree I can set up the apparatus in question—then tell me what you expect the counting rate in the counters will be.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

Feynman’s archived papers do not contain any further response from Mr. Y.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO DOUGLAS M. FOWLE, SEPTEMBER 4, 1962

A magazine article on Feynman and Caltech caught Mr. Fowle’s eye, and he wrote to discuss Caltech’s startling attrition rate of 35 percent. Mr. Fowle pointed out that Caltech accepted only 180 students out of 1,500 of the best and brightest applicants. He went on to say, “the force-out of so much as 35% entails a misdirection of faculty teaching time and talent as well as shameless cruelty to scores of fine young men.”

Mr. Douglas M. Fowle

Milwaukee,Wisconsin

Dear Sir:

I do not think that the methods of selection of freshmen at Cal Tech are good. I have never paid a great deal of attention to it, being “busy” with other things. This is not an excuse but an admission of irresponsibility. Thank you for your letter; perhaps it will help prod me into paying more attention to the problem.

There is today, in my opinion, no science capable of adequately selecting or judging people. So I doubt that any intelligent method is known.

I am not sure, but it is even possible that a large drop-out rate is not a result of selection but of what happens to the poor guys when they get here. For example, a student that has been at the very top of his class for all his previous schooling, finding himself below average at Cal Tech may have a 2:1 chance to get discouraged and drop out, for psychological reasons. No matter how we select them, half the students are below average when they get here.

These human problems are very difficult, and I don’t know much about them—but I believe nobody really knows very much about them either.

Thank you for your letter—I surely will be more attentive when such matters are discussed in the future.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO GWENETH FEYNMAN, 1962

Grand Hotel

Warsaw

Dearest Gweneth,

To begin with, I love you.

Also I miss you and the baby and Kiwi, and really wish I were home.

I am now in the restaurant of the Grand Hotel. I was warned by friends that the service is slow, so I went back for pens and paper to work on my talk for tomorrow—but what could be better than to write to my darling instead?

What is Poland like? My strongest impression—and the one which gives me such a surprise—is that it is almost exactly as I pictured it (except for one detail)—not only in how it looks, but also in the people, how they feel, what they say and think about the government, etc. Apparently we are well informed in the U.S. and the magazines such as Time and Atlas are not so bad. The detail is that I had forgotten how completely destroyed Warsaw was during the war and therefore that with few exceptions (which are easily identified by the bullet holes all over them), all the buildings are built since the war. In fact it is a rather considerable accomplishment—there are very many new buildings—it is a big city, all rebuilt (from 7/8 destruction). Of course, as you know the genius of builders here is to be able to build old buildings. And so it is—there are buildings with facings falling off—walls covered with concrete with patches of worn brick showing thru—rusted window bars with streaks of rust running down the building, etc. Further, the architecture is old—decorations sort of 1927 but heavier—nothing interesting to look at (except one building).

The hotel room is very small, with cheap furniture, very high ceiling (15 feet), old water spots on the walls, plaster showing through where bed rubs wall, etc. It reminds me of an old “Grand Hotel” in New York—their faded cotton bedspread covering bumpy bed, etc. But the bathroom fixtures (faucets etc.) are bright and shiny—which confused me—for they seemed relatively new in this old hotel. I finally found out—the hotel is only three years old—I had forgotten about their ability to build old things. (No attention at all yet from waiter—so I broke down and asked one who was passing for service—a confused look—he called another over—Net result: I am told there is no service at that table and am asked to move to another. I make angry noises—action?—I am put at another table (given a menu and 15 seconds to make up my mind) and order SZNYCEL PO WIEDI-ENSKU (Wiener Schnitzel).

On the question of whether the room is bugged. I look for covers of old sockets (like the one in the ceiling of our shower).There are five of them, all near the ceiling—15 ft—I need a ladder and decide not to investigate them—but there is one similar large square plate in lower corner of room near the telephone—I pull it back a little (one screw was loose). I have rarely seen so many wires—like the back of a radio—what is it—who knows—I didn’t see any microphones—the ends of the wires were taped (like connections or outlets no longer in use). Maybe in the tape is the microphone—well I haven’t a screwdriver and don’t take the plate off to investigate further. In short—if it isn’t bugged they are wasting an awful lot of wires.

The Polish people are nice, poor, at least have medium style in (soup arrives!) clothes, etc., so there are nice places to dance to bands, etc. so it is not very heavy and dull—as one hears Moscow is. On the other hand you meet at every turn with that kind of dull stupid backwardness characteristic of government—you know like the fact that change of $20 is not available when you want to get your card renewed at the American Immigration Office downtown. Example, I lost my pencil and wanted to buy a new one at the “Kiosk” here. Pen is $1.10—No, I want a pencil—wooden with graphite. No, only $1.10 pens. O.K. how many Zlotys is that?You can’t buy it in Zlotys only for $1.10. Why—who knows. So I have to go upstairs for American money. Give $1.25—No, cannot give change—must go to the cashier of the hotel—the bill being written in quadruplicate of which the clerk keeps one, the cashier one, and I get two copies.What shall I do with them? On the back it says I should keep it to avoid paying customs duties. It is a Paper-mate made in the USA (the soup dish is removed).

The real question of government versus private enterprise is argued on too philosophical and abstract a basis.Theoretically planning may be good etc—but nobody has ever figured out the cause of government stupidity—and until they do and find the cure all ideal plans will fall into quicksand.

I didn’t guess the palace in which the meetings are held right. I imagined an old forbidding large room—from 16th century or so. I forgot that Poland has been so thoroughly destroyed.The palace was brand new—we are in a round room with white walls with gilt decorations—and a balcony and ceiling painted with a blue sky and clouds—(The main course comes—I eat it—it is very good—I order dessert (pastries with pineapple 125 g)—incidentally the menu is very precise—the 125 g is the weight—125 grams! Things like “filet of herring 144g” etc. I haven’t seen anybody checking with a scale that they are not cheated—I didn’t check if the Schnitzel was the claimed 100 grams). I am not getting anything out of the meeting—I am learning nothing.This field (because there are no experiments) is not an active one, so few of the best men are doing work in it. The result is that there are hosts (126) of dopes here—and it is not good for my blood pressure—such inane things are said and seriously discussed—and I get into arguments outside the formal sessions—say at lunch—whenever anyone asks me a question or starts to tell me about his “work.” It is always either—(1) completely un-understandable, or (2) vague and indefinite, or (3) something correct that is obvious and self-evident worked out by a long and difficult analysis and presented as an important discovery, or (4) a claim, based on the stupidity of the author that some obvious and correct thing accepted and checked for years is, in fact, false (these are the worst—no argument will convince the idiot), (5) an attempt to do something probably impossible, but certainly of no utility, which, it is finally revealed, at the end, fails (dessert arrives—is eaten), or (6) just plain wrong. There is a great deal of “activity in the field” these days—but this “activity” is mainly in showing that the previous “activity” of somebody else resulted in an error or in nothing useful or in something promising, etc.—like a lot of worms trying to get out of a bottle by crawling all over each other. It is not that the subject is hard—it is just that the good men are occupied elsewhere. Remind me not to come to anymore gravity conferences.

I went one evening to the home of one of the Polish professors (young—with a young wife). People are allowed seven square yards per person in apartments—he is lucky and has 21 for he and his wife—living room, kitchen, bathroom. He was a little nervous with his guests—(myself, Professor and Mrs.Wheeler and another) and seemed apologetic that his house was so small (I ask for the check—all this time the waiter has between two and three active tables including mine), but his wife was very relaxed and kissed her Siamese cat “Boobosh” just like you do with Kiwi. She did a wonderful job—the table for eating had to be taken from the kitchen—a trick requiring the bathroom door to be first removed from its hinges. (There are only four active tables in the whole restaurant now—four waiters).The food was very good and we all enjoyed it.

Oh, I mentioned that one building in Warsaw is interesting to look at—it is the largest building in Poland—the “Palace of Culture and Science” given as a gift by the Soviet Union—designed by Soviet architects, etc. Darling, it is unbelievable! I cannot describe it—it is the craziest monstrosity on land! (The check comes—brought by a different waiter—I await the change).

This must be the end, I hope I don’t wait too long for the change. I skipped coffee because I thought it would take too long. Even so, see what a long letter I can write while eating Sunday dinner at the Grand Hotel.

I say again—I love you, and wish you were here—or better I were there. Home is good. (The change has come. It is slightly wrong (by 0.55 zloty = 15¢) but I let it go.)

Good bye for now.

Richard.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO THOMAS K. MOYLAN, MARCH 25, 1963

Feynman was appointed to the California Curriculum Commission on March 14, 1963, and soon began the long process of evaluating textbooks used in the state’s public schools.

Mr.Thomas K. Moylan

Manager, Pacific Division

Silver Burdett Company

San Francisco, California

Dear Mr. Moylan:

Thank you for your letter of congratulations. In it you submitted some literature on your books and suggested that we meet. I have not read your material. I would feel uncomfortable to discuss the textbooks with any one publisher without doing the same for all. But to do the latter would take more time than I have available.

I expect to spend most of what time I have in going carefully over each of the textbooks submitted. I hope you do not feel I am being unfair to you. I am sure your books will speak for themselves.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

There were similar responses to other publishers, including Scott, Foresman and Company, and Laidlaw Brothers.

ERNEST D. RIGGSBY TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, APRIL 17, 1963

Dear Dr. Feynman:

I am presently engaged in a doctoral research project concerning the nature of scientific methods as interpreted by active research scientists and philosophers of science. Realizing that the bibliographic resources often do not contain critical listings, I am forced to ask for certain assistance directly from certain scientists. If you could give some assistance to this effort, it would be greatly appreciated.

If you are willing, please briefly comment on your interpretation of the scientific method or scientific methods.

We have searched the standard bibliographic sources for statements by eminent scientists, such as yourself, on this topic. It is believed however, that some up-to-date statements directly from these scientists would greatly facilitate our program.

This request for assistance is not meant to infringe on the valuable time of anyone. If you find it inconvenient or undesirable to assist this effort, we shall, of course, understand.

We note that a sizable number of our science textbooks at all grade levels present the scientific method as more rigid than many practicing scientists consider it to be.We further trust that this letter of inquiry will help us to find certain more realistic description of this topic.

If you do not have time or do not wish to make a written response to this request, perhaps it will be possible for you to direct us to sources in which you have already made statements concerning the scientific methods—often such statements are included in articles which would not be indexed under the heading: scientific method.

Permission to quote you is respectfully requested.

Very truly yours,

Ernest D. Riggsby

Associate Professor

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO ERNEST D. RIGGSBY, APRIL 30, 1963

Professor Ernest D. Riggsby

Troy State College

Troy, Alabama

Dear Professor Riggsby:

I am sorry that I have no published statements on the “scientific method.” I have just given three lectures (called John Danz Lectures) at the University of Washington, the first and third of which contain remarks on the subject. How soon they will be published (from recorded tapes), I do not know.

Briefly, however, the only principle is that experiment and observation is the sole and ultimate judge of the truth of an idea. All other so-called principles of the scientific method are by-products of the above which depend on the nature of the material and what is found out. There are, furthermore, a number of tricks (like reasoning from analogy, or choosing the “apparently simplest” explanation) which have been found to increase the ease with which we cook up new ideas to subject to the test of experience.

Sincerely,

R. P. Feynman

L. G. PARRATT TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, AUGUST 30, 1963

Dear Dick:

Did you ever write that letter to me so that I may transmit it to the Messenger Lectures Committee so that they can ask our President (of Cornell, that is) to extend to you the official, formal invitation?

Incidentally, a recent letter from the Commission on College Physics asks if they could put your Messenger Lectures here on video tape for a larger audience. I don’t know what the Messenger Lectures Committee might say about this, but, first, what do you think?

Coffee hour at Caltech, June 1964.

Sincerely yours,

L. G. Parratt

Chairman

The Messenger Lectures have taken place annually since 1924, when Cornell grad and professor Hiram Messenger established a fund “to provide a course of lectures on the evolution of civilization for the special purpose of raising the moral standard of our political, business, and social life.”

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO DR. L. G. PARRATT, SEPTEMBER 6, 1963

Dr. L. G. Parratt

Chairman, Department of Physics

Cornell University

Ithaca, New York

Dear Lyman:

I don’t know what you want in your letter of August 30. If I am invited to give the Messenger Lectures I will be happy to accept. My subject would be “The Character of Physical Law”—the title of each individual lecture (how many are there—six?) will be hard to decide until the last minute (unless you insist strongly enough).

With regard to the video tape, I don’t know what it is like to do that. All I care about is that it should not be distracting in any way. No strong special lights—no nearby camera in the front of the audience—no mess of cables all over the floor, etc. A simple camera in the projection booth or in the back is O.K. If it can be done so it is not obvious that is being done, so the audience is not disturbed by technicians jumping around and moving lights or cameras around, I see no objection, unless the committee feels it isn’t a good idea.

I hope this letter is what you asked for.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

Feynman gave a series of seven Messenger Lectures in November 1964.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO D. BLOKHINTSEV, JUNE 25, 1964

D. Blokhintsev, Chairman

Organizing Committee

Joint Institute for Nuclear Research

Moscow, U.S.S.R.

Dear Sir:

Thank you very much for your invitation to the Dubna Conference. I have thought a good deal about the matter and would have liked to go. However, I believe I would feel uncomfortable at a scientific conference in a country whose government respects neither freedom of opinion of science, nor the value of objectivity, nor the desire of many of its scientist citizens to visit scientists in other countries.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

D. S. SAXON TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, OCTOBER 15, 1964

Dear Professor Feynman,

Dr. Marvin Chester is presently under consideration for promotion to the Associate Professorship in our department. I would be very grateful for a letter from you evaluating his research contributions and his stature as a physicist.

May I thank you in advance for your cooperation in this matter.

Sincerely,

D. S. Saxon

Chairman

Dick:

Sorry to bother you but, unfortunately, we really need this sort of thing.

David S.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO D. S. SAXON, OCTOBER 20, 1964

Dr. D. S. Saxon, Chairman

Department of Physics

University of California, Los Angeles

Los Angeles, California

Dear David:

This is in answer to your request for a letter evaluating Dr. Marvin Chester’s research contributions and his stature as a physicist.

What’s the matter with you fellows, he has been right there the past few years—can’t you “evaluate” him best yourself? I can’t do much better than the first time you asked me, a few years ago when he was working here, because I haven’t followed his research in detail. At that time, I was very much impressed with his originality, his ability to carry a theoretical argument to its practical, experimental conclusions, and to design and perform the key experiments. Rarely have I met that combination in such good balance in a student.Was I wrong? How has he been making out?

Sincerely yours,

R. P. Feynman

The above letter stands out in the files of recommendations. After this time, any request for a recommendation by the facility where the scientist was working was refused.

R. C. FOX TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, OCTOBER 26, 1964

Dear Prof. Feynman,

I can’t tell you how much I enjoyed reading and studying Vol. I of your “Lectures in Physics.”There is so much one can say about that book and really so little time to say it. So many books I have hammered and tonged at only to finally get lost before I reached the goal besides being so dry and dusty between cases. True, the rewards gained were worth the effort but so difficult are the ways. So many “obvious” steps are left out, nothing left but the bones, desiccated and almost uninteresting.

Why is it so many lousy books are written, lousy for me anyway and why does a gem like yours come by so rarely?

Surely your conversational like style adds so much. It reminds me of the dialogues of Galileo which started the whole thing. I know that the tendency toward brevity is appreciated by some but not by me.

And the way you handle the interesting little sidelights which I and others have certainly wondered about, but have been afraid of raising the stupid question so necessary to get the answer that you have given us.

Talk about wine; man that book of yours is really intoxicating. I can hardly wait for Vol. II. I’m sure I’m expecting too much but I sure wish there were going to be a Vol. III, IV, V, etc. all built on one another. If you need any encouragement I surely would like to furnish some. Boy would I like to get the lowdown on such things as Tensors, Group Theory, Quantum Mechanics etc. on the same basis as Vol. I. But again that’s hoping too much, but I never give up hoping I guess.

Thanks again for that very enjoyable Vol. I. I have a feeling it may revolutionize Freshman Physics. It oughta. It beats Sears so hollow I hope we never have to mess much with that again.

Sorry if I sound off the deep end, but I am. Don’t let those stuffed shirts discourage you; you’ve done a wonderful job. Don’t stop now if at all possible.

Respectfully,

R. C. Fox

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO R. C. FOX, JANUARY 4, 1965

Mr. R. C. Fox

San Rafael, California

Dear Mr. Fox:

Thank you for your “fan” letter. I did have some trouble with “Editors.” Volume I was edited by Leighton and he did a great job, leaving in all the little tidbits and sidelights.Volume II is out now. It was edited by an elaborate organization and I was embarrassed to have to say “put that back in” so often—who am I who thinks every word he utters is so wonderful? Also, the original lectures for Volume II weren’t as good as for Volume I anyway. Have patience—Volume III is coming out in a few months—I hope. (Tensors are in Volume II, Quantum Mechanics in Volume III—sorry, no group theory—and no Volume IV,V, etc. I am done, for a while at least.)

Thanks again for the encouragement.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

BETSY HOLLAND GEHMAN TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, DECEMBER 1, 1964

Dear Dick:

Many, many years ago, you were at Brookhaven and I was in a ridiculous show at the John Drew Theatre in Easthampton. If that doesn’t jog your memory, let’s try this: I’m a friend of your cousin Peggy Phillip’s.

But, of course you remember.

Let’s assume all the usual amenities have been exchanged, and I’ll get down to business.

Your name has appeared in a number of places in recent years, with enough information to make your work sound interesting and important (which it always was, heaven knows). Has anyone done a long profile of you for a national magazine? If not, I would like to. It does not need to include anything about work you are doing which may be classified, but I do think a simple, clear, understandable explanation of just what you mysterious scientists are like would help to break down that barrier C. P. Snow is always ranting about. As I remember you, your language and imagery were fun, as well as instructive, and you were, if you’ll pardon the expression, offbeat.

In recent years I have been working as a writer and editor for magazines, and have a book on twins and twinning about to be published by Lippincott (I have twins of my own). I have had some correspondence on multiple births with your confrere, Albert Tyler.

If I have your permission, I would like to submit you as a subject to either the Saturday Evening Post or Fortune Magazine. Please let me know if you are agreeable.

I heard from Peggy that you are happily married, and a father. I’m happy for you on both counts.

I look forward to hearing from you at your earliest convenience, as they say in business-like letters.

Best regards,

Betsy Holland Gehman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO BETSY HOLLAND GEHMAN, JANUARY 4, 1964

Mrs. Betsy Holland Gehman

Carmel, New York

Dear Betsy,

Of course, I remember you very well.

You certainly flatter me by wanting to do a profile for a great big national magazine. I was tempted, but I think I had better crawl deeper into my ivory tower and let C. P. Snow go on ranting. Perhaps for scientists, as for women, our charm is in our mystery. Presumptuous, no—surely women have charm, but scientists?

Anyway, thanks for thinking of me in such a flattering way.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

LAWRENCE CRANBERG TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, JANUARY 6, 1965

Dear Professor Feynman:

I have just come across your article “The Relation of Science and Religion.”This is a topic some of whose aspects we might try to include in a course presently being organized on science for undergraduates. I would welcome an exchange of views with you on this challenging subject. At the moment let me take issue with you on your statement that “moral questions are outside of the scientific realm.”

It was pointed out by Darwin (Descent of Man, Chap. IV) that ethical codes are not unique to homo sapiens, and represent a form of social adaptation favorable to survival. As such are they not properly subject to scientific study and improvement?

The distinction between “will” and “should” propositions may be more one of emphasis than of kind. I suggest that moral exhortation is an abbreviated form of conditional prediction, where the condition is often omitted because it is essentially the sine qua non of society: survival. What is the logical difference between statements such as: “if a particle goes from A to B in the minimum time it will follow a parabola”, and the statement “if X is to survive he should learn to live with his neighbors”? Considering the very idealized circumstances under which the first is true, and the role of the uncertainty principle, the “will” is an overstatement about any physical system, and the two statements are logically identical. May not the golden rule be a sort of Fermat principle applied to society?

To insist that ethics and science are separate may confuse and weaken both. If Darwin is right, ethics require constant change to adapt to the changing requirements of survival.To exclude science—the quest of reason—from this process of adaptation seems to exclude it from its primary role.The effective functioning of science itself depends vitally on adherence to canons of conduct which are clearly “ethical”—a fact conspicuously clear in our times when we see those canons suffering significant erosion (while the leadership of science stands by).

Sincerely yours,

Lawrence Cranberg

Professor of Physics

LAWRENCE CRANBERG TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, JANUARY 6, 1965

Dear Prof. Feynman,

Rereading my too hastily dispatched letter of this morning I wish I had omitted the phrase “in the minimum time” in the midst of the third paragraph, and the query at the end of that paragraph.

On the golden rule, let me refer instead to the final page of the chapter of Darwin, cited in my original letter.

The term “leadership” in the last paragraph is to be interpreted as referring to the leadership of several important organizations of scientists.

Sincerely yours,

Lawrence Cranberg

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO LAWRENCE CRANBERG, MARCH 3, 1965

Professor Lawrence Cranberg

Department of Physics

University of Virginia

Charlottesville,Virginia

Dear Professor Cranberg:

Thank you for your letter discussing “The Relation of Science and Religion.” I didn’t really intend to insist that ethics and science are separate, but rather that the fundamental basis of ethics must be chosen in some non-scientific way. Then, when this is chosen, of course, science can help to decide whether we should or should not do certain things. Science can help us see what might happen if we do them, but the question as to whether we want something to happen depends on a choice of the ultimate ethical good. As you mentioned, such a choice then does not say there’s a separation of the fields, and we cannot argue about the choice for the ultimate good of each.You have chosen survival as an ultimate value, then there is no longer any non-science ethic that serves the ultimate value. If we have two alternate ways in which we might survive, one in which the survivor is secure, but miserable, and the other that we are equally secure in the survival, but not happy in the living or our willingness to choose between them, from survival of what is the right race of individuals—how to balance the two—could the survival of the German Reich justify the actions of the tyrant and a religious martyr’s values because they put individual survival below some greater good?

All I am trying to do is cast some doubt or confusion into the principle that survival permits ethics without question and that all people will agree that survival is the real determinate of good. If you can see that there may be some doubt about that, who would resolve the doubt for science?

So, there is no logical difference between the statements “if a particle goes from A to B in the minimum time, it will follow a parabola,” and “if x is to survive, he should learn to live with his neighbor.”

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO ALAN SLEATH, APRIL 7, 1965

The following letter refers to a transcript of Feynman’s Messenger Lectures,

later published in book form as The Character of Physical Law.

Mr. Alan Sleath

The British Broadcasting Corp.

London, England

Dear Alan and/or Fiona:

I am returning Lectures 4 thru 7 to you. I think they are rather poor in their present forms as the English is horrible—the sentence structure atrocious! (I appreciate that these atrocities are of my own doing.) I do not have the time to edit these lectures into reasonably-readable English. I have made some minor corrections to make the physics clearer, but I do not have time to do more than this.

I understand that your intention is to publish these so that you have something to give to the people to refer to. I am willing to go along with that even if you publish it in its present form; however, to protect my reputation in this regard, could some statement be made or explanation given. Possibly in the preface you could say that these lectures were not given from a prepared manuscript—that this is a verbatim, direct report, presented before a live audience who could see me waving my arms, etc.

You may wish to decide after reading the results of these lectures in printed form that you don’t want to publish them at all. If this is the case it will be perfectly satisfactory to me.

Kindest personal regards and many thanks.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO R. E. MARSHAK, MAY 18, 1965

Mr. R. E. Marshak

Department of Physics and Astronomy

The University of Rochester

Rochester, New York

Dear Marshak:

I am sorry, but I shall not have time to write the article you want for the Bethe volume.You make me feel uncomfortable—I like Hans so very much that I feel I “ought” to do what you want—but who invented this infernal idea of writing an article for a guy when he gets to be 60? Isn’t there an easier way to show friendship and regard? I feel like I feel on “Mother’s Day.”

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

BARBARA KYLE TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, AUGUST 13, 1965

To Richard Feynman from an ignorant layman on first hearing (but not yet having read—it’s on order) the Messenger Lectures.

What do I understand? That when you go to count which particles through which holes have made their way, the light you shine to let you see, changes the situation and makes them—as who would not—disappear.

I understand that when you want to see how fast they go or exactly what they look like, you alter their speed and change their character.

So we, under new carbon street lights, turn green and turn away, both from the ugly glare and your too curious inspection; and having escaped detection—reappear.

At a deeper level I can understand that you feel the need to question your assumptions—data—what you take for granted.

If you’ve invented them to play out roles in your equations, perhaps there are more of them than you’ve allowed for, and these slip past unrecognized, uncounted through the holes.

I can understand that you want all your not-yet-proved-wrong hypotheses to be together reconcilable, and that just now this is not so.

The maths give you, you say, infinity when you’d expected (what was it? I didn’t catch it) was it zero? Or another number preconceived? If zero—is that so different from infinity? Both of them circles?

I know, I know, to ask this question, or any others I am likely to thinking, is to offer a six-figure combination for a known five-figure lock and I apologize for this futility.

Then as a layman what from your lectures do I learn? What Message gets across to my rapt ignorance? I only know the Lecturer has an honest face.

All that I understand of what he says makes sense. All that I fail to understand feels like it’s sense. I understand that as the explanations click into place the whole is beautiful, and then the tourists come and leave their litter.

But then you’ll move on to biology, and I wish I might be there to see it.

Barbara Kyle

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO BARBARA KYLE, OCTOBER 20, 1965

Miss Barbara Kyle

Dorking, Surrey

England

Dear Ms. Kyle,

May I thank you for your letter.

From the list of “What do I Understand” I am very happy to see so much really understood.You get a high grade from the professor—perhaps 90%. Not 100% because you didn’t understand why getting infinity from a calculation is so annoying.

Thinking I understand geometry and wanting to cut a piece of wood to fit the diagonal of a five foot square, I try to figure out how long it must be. Not being very expert, I get infinity—useless—nor does it help to say it may be zero because they are both circles. It is not philosophy we are after, but the behavior of real things. So in despair, I measure it directly—lo, it is near to seven feet—neither infinity nor zero. So, we have measured these things for which our theory gives such absurd answers. We seek a better theory or understanding that will give us numbers close to what we measure. We are seeking the formula that gives the square root of fifty.

Will you think it is only politeness if I say sincerely, I rarely find from laymen such real understanding as I find in your letter?

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

” (I thought it, but controlled myself.)

” (I thought it, but controlled myself.)