1966-1969

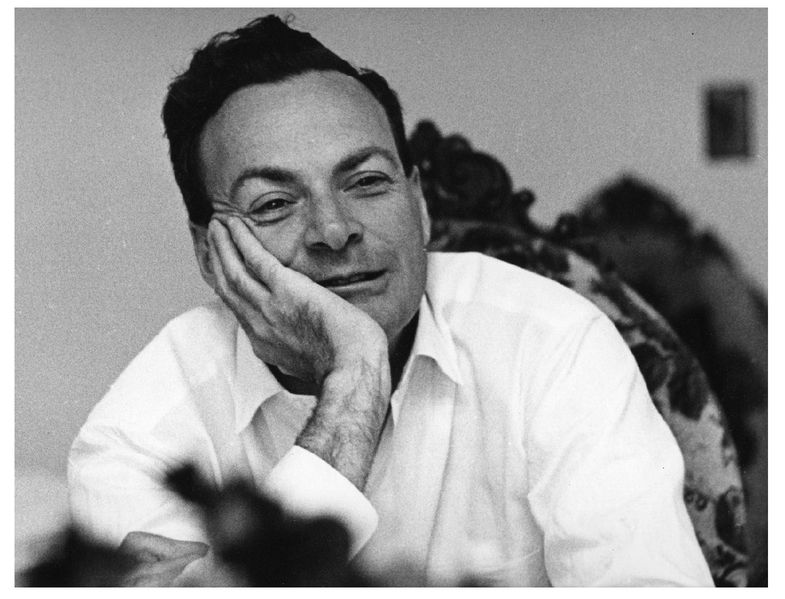

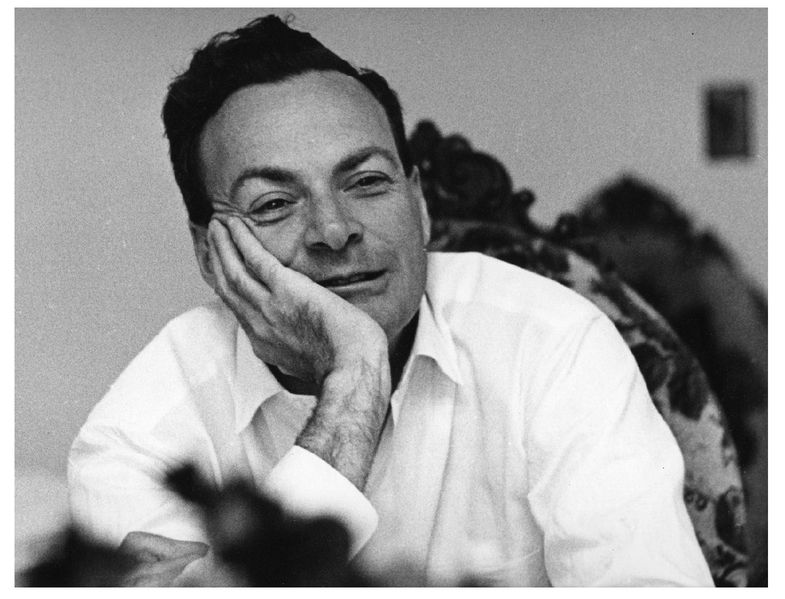

Although the Nobel Prize brought Feynman greater international recognition, as evidenced by the letters that follow, such acclaim was not without its pitfalls. As people wrote in from Switzerland to Australia, India to Hungary, he began saying “no” more often to the many requests for his time and expertise.

A notable exception was made, however, for continuing work on the California State Curriculum Committee, though he had officially resigned in 1964. In a lengthy memo sent in April 1966 to a Mrs. Whitehouse, a member of the Curriculum Committee, he commented on the relative merits of science textbooks written for elementary school students. Among his remarks was a theme that he revisited many times throughout his career:

One gets the impression then that science is to be a set of pat formulas to standard questions. “What makes it move,” quickly all hands are eagerly raised, the lesson is learned, they are to say “Energy makes it move,” “Gravity makes it fall,” “The soles of our shoes wear out because of friction.” Just words, nothing is explained. It is like just saying “Because of God’s will” and having nothing left to look into.

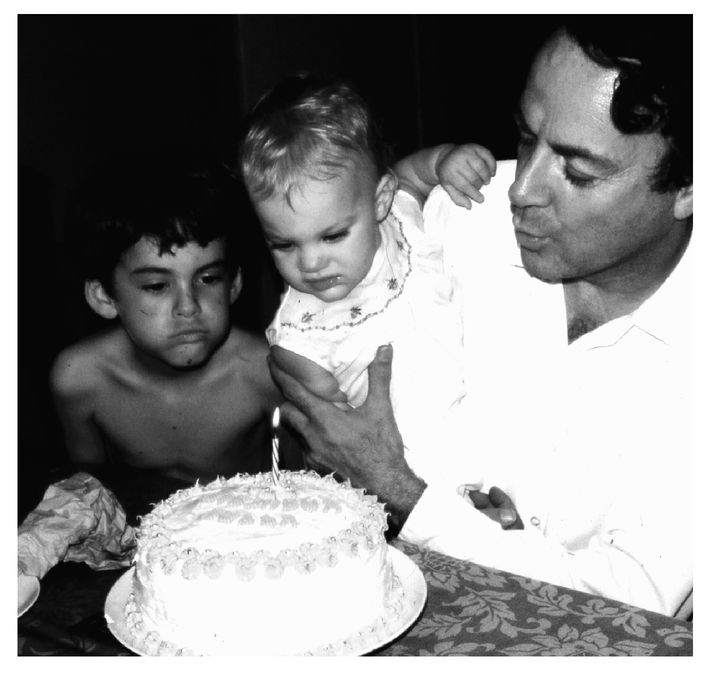

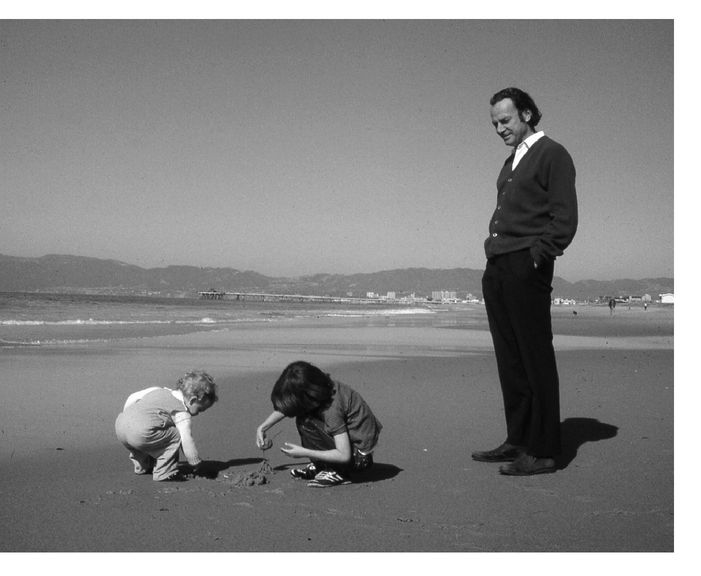

Judging from this memo and other letters he chose to answer, the teaching of physics, and science in general, was now his central concern. I particularly enjoyed reading that he and my brother, Carl (then 3 1/2), did some of the experiments in one of the books under review. It was a harbinger of the strong relationship and intellectual partnership that would develop between them.

In 1967, Feynman was offered his first honorary degree—from the University of Chicago. He declined to accept it, as he would every other such offer.

In 1968, I was adopted.

VIRENDRA K. SINGH TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, OCTOBER 17, 1965

Dear Mr. Feynman—

Long ago I started studying your books which I have finished: My heartiest congratulations for your achievement, as the books are a landmark. I just do not find words how to appreciate them.To put a most difficult theory in a most easy way is a big game and not everybody can do it. I have recommended these books to the head of department and emphasized that every student must have these copies:They are to be read very thoroughly like Ramayana of Hindus.

I have been tremendously influenced by your work and please let me know your academic achievements. As a matter of fact I consider you to be “My Ideal Lecturer” and request you for a full size photograph with your signatures: I would like to have it in my University Dept.

I hope you shall write back. Please do send photograph.

Thanks:

V. K. Singh

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO VIRENDRA K. SINGH, NOVEMBER 23, 1965

Dr.Virendra K. Singh

Rajasthan University

Jaipur, India

Dear Dr. Singh:

Thank you very much for your kind and flattering note of congratulations. I am enclosing a photograph for you.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

VIRENDRA K. SINGH TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, FEBRUARY 7, 1966

Respected Dr. Feynman,

It really hurts me that you have misinterpreted my deep sense of regards and intrinsic faith to you.You have perhaps misfitted the word “flattering.” It was partly due to me as I knowingly did not write you I am a physics previous student here. I was afraid you wouldn’t send me the photograph. Look! Unpremeditated stream of thoughts for one’s praise (which one richly deserves) is NOT flattery. People have different techniques of putting things, mine was simple and straight forward.

I understand one cannot expect such letter (No.1) from a Professor, and it was natural on your part to understand it the other way round.

Believe it, I have just installed your photograph right on my working table.

Thanks: V.K. Singh

Physics

PS You need not reply, because busy people like you cannot spare much.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO VIRENDRA K. SINGH, FEBRUARY 14, 1966

Dear Dr. Singh:

I am so sorry to have hurt you by my careless misuse of language. I did not mean to imply that your letter was insincere in any way.The word “flattering” was wrongly used, as I have just looked it up in the dictionary and found it has negative connotations, which I certainly did not mean. I should have used some word like “complimentary” instead.

If you knew me well, you would know that I am immodest enough to take all compliments at their face value and not to think that they might be idle flattering. I just didn’t know what the word really implied.

I was sincerely pleased, even nearly overwhelmed by your comparison of my lecture notes with the Ramayana.

I hope I have made no further errors in this letter, and that you no longer feel hurt or uncomfortable in any way as a result of our correspondence.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO J. M. SZABADOS, NOVEMBER 30, 1965

J. M. Szabados

Victoria, Australia

Dear Miss Szabados:

Thank you very much for your kind note about my lectures. I am glad you like them, and glad you took the time to write to me and tell me. It seems to me that there is some chance that you may be successful since you say you have not studied physics in a disciplined fashion. So much the better, but study hard what interests you the most in the most undisciplined, irreverent and original manner possible.

Best of luck in your endeavor.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO E. U. CONDON, DECEMBER 6, 1965

Dr. E. U. Condon

Joint Institute for Laboratory Astrophysics

University of Colorado

Boulder, Colorado

Dear Ed:

I had trouble writing the citation for Abram Bader, because I am personally involved, it is almost like trying to write my own. The best I could do follows:

“Mr. Bader is cited for his superb teaching of an exceptional student. Usually the truly outstanding student is left to go his own way. But when Abram Bader found Richard Feynman (who this year shared the Nobel Prize in physics) in his class he gave the boy great challenges, good advice and fascinating new information about physics. He excused him from paying attention in class but challenged him to use the time to learn advanced calculus from a book from his personal library. He fascinated him by explaining to him the principle of least action, a central point of almost all of Feynman’s work. Finally the student’s love and admiration for his teacher resulted in the boy’s wanting to become a teacher and scientist. Bader gave good counsel.”

The remark at the end is supposed to be subtle humor. He persuaded me, with considerable effort, to become a scientist of course.You may prefer to make it clearer, or avoid the “humor” as it may bother many of the teachers. I trust your judgment. Change the whole thing in any way you wish.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

RAYMOND R. ROGERS TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, DECEMBER 17, 1965

Dear Sir:

I watched and listened to your discussion with members of K.N.X.T.’s news commentators tonight and was amazed at the colossal ignorance and smugness of your learning and achievements.Your use of the term “you guys” in your talk was sickning.

Your comments on smog was of a man intirely ignorant of the problem. You say there are many other problems more important than smog.With a civilization slowly dying in their own filth, what may these problems be? It will be solved just as soon as the financial hurt to the manufucturers and oil companys will be overcome.

I have never progressed beyond high school. My ambition was to attend Throop College which is now Cal Tech. My I.Q. was too low to get in. I served my apprenticeship as a machinist starting at ten cents an hour. My whole life has been to be the best machinist there was.

When I was retired from Technical Labortories (now T.R.W. Systems) on account of age I had worked up as far as I could go without a degree. Your smart young men from Cal. Tech. came over to tell me how things should be done. It sounded like the prattle of small children.

One part of the O.G.O. satalite was so poorly designed I told them so, and I could design one that would really work.They laughed at me, (a poor slob without an education).Two years later when O.G.O was was put into orbit that part was on O.G.O. exactly as I designed it.

Your discussion on atomic Energy was hardly of a man of letters.Your technical gobbledegook did not impress me one bit. Some times I think education is a handicap.

How did you get the Nobel Prize?

Yours Truly,

Raymond R. Rogers

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO RAYMOND R. ROGERS, JANUARY 20, 1966

Mr. Raymond R. Rogers

Gardena, California

Dear Mr. Rogers:

Thank you for your letter about my KNXT interview.You are quite right that I am very ignorant about smog and many other things, including the use of the finest English.

I won the Nobel Prize for work I did in physics trying to uncover the laws of nature. The only thing I really know very much about are these laws. I was asked by the TV station to appear on their news interview program, but what happened was that they asked me all kinds of questions about which I didn’t know anything. I had to answer them somehow or other, and I did my best, which you say is none too good.

But, we are both in the same boat, because although you have become a very good machinist and I a good scientist, neither of us really know about the smog problem. Just as my comments on it seem ignorant to you, so your comments on it in your letter do not seem so wise to me.

How would you like to receive a prize for being a great machinist, and then get on the TV to be interviewed by a group of men who don’t care a bit about machining and its problems, but instead ask questions about smog? The thing that hurts is that they don’t ask you about things that you love and have devoted your life to and received the prize for.

So, please excuse the fact that I wasn’t happy and polite during my interview, and had to answer questions about which I had no particular special knowledge.

By the way, one of my ambitions had been to be at least good in the machine shop, but everything I made fit poorly, my bearings wobbled, etc. Good machining is essential to building good apparatus for the precise and careful measurements required in physics to discover Nature’s laws. So, we physicists have always worked close to and depended on men like you and some of us (like Rowland, who made the first very precise ruling engines to make diffraction gratings) have been great machinists.

About using the words “you guys”—I am sorry it offended you, but it is because I never believed that people who used big words and very fancy speech were especially smart or good. I think it is important only to express clearly what you want to say. I admit though, that “you guys” doesn’t sound polite, so I guess that wasn’t so good.

Yours sincerely,

R. P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO GILBERTO BERNARDINI AND LUIGI A. RADICATI, FEBRUARY 9, 1966

Professors Gilberto Bernardini

Luigi A. Radicati

Scuola Normale Superiore

Pisa, Italy

Dear Colleagues:

Very many thanks for your invitation. I liked Pisa and Tuscany and would surely enjoy being with you. My real trouble is that I like it here too.

I have a nice cozy house with a good family in it, and I do not like to move everything temporarily to Italy for such a long period. I am a stick-in-the-pleasant-mud type of guy.

Thank you again, anyway. Someday shorter periods might be a possibility but a year is too much.

Yours sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

J. W. BUCHTA TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, FEBRUARY 18, 1966

Dear Professor Feynman:

The following “problem” has been given to us as the topic for a note in The Physics Teacher. A lawn sprinkler of the type sketched here rotates clockwise when water is ejected from the nozzles. It also rotates clockwise when placed underwater. How would it behave when placed underwater but the direction of flow reversed, that is water enters the nozzles and flows into the connected hose? The problem was labeled Feynman’s problem, I assume because you may have proposed it.Would you be willing to contribute a note on it for publication in The Physics Teacher?

The question appears to afford an opportunity to discuss symmetry, reversibility as well as fluid mechanics. I am sure our readers would appreciate a note from you regarding this problem. I hope I may have a favorable reply from you.

Sincerely,

J.W. Buchta

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO J. W. BUCHTA, MARCH 3, 1966

Mr. J.W. Buchta

Editor

The Physics Teacher

Washington, D.C.

Dear Mr. Buchta:

The lawn sprinkler problem should not, please, be labeled “Feynman’s problem.” I first heard of it from somebody at Princeton when I was a graduate student.We had several discussions, and I did an experiment verifying expectations (which ended in a minor catastrophic explosion).The problem appears in E. Mach’s “Science of Mechanics” published in 1883 (translated 1893 by McCormack, published by Open Court Publishing Co., see page 299, in connection with Figure 153a).

I have no other comments to make for the Physics Teacher.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

The lawn sprinkler problem also makes an appearance in Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! : “The answer is perfectly clear at first sight. The trouble was, some guy would think it was perfectly clear one way, and another guy would think it was perfectly clear the other way.”

THOMAS J. RITZINGER TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, MARCH 2, 1966

Dear Dr. Feynman:

I am a physics teacher in Northwestern Wisconsin, teaching five classes of PSSC Physics per day. Because of our geographical location, it is extremely difficult for my students to be able to talk to or visit with scientists and research people very easily.

I thought that, with your cooperation, it might be possible to give them an experience which, I am sure, they will remember for a long time to come. I was wondering if you would consider sometime in the future talking to my students by a long distance telephone connection by way of an appointment call. I would be very happy to fit such a call into your schedule and would be able to have all my students gather into our auditorium so that they might listen to you and possibly ask a few questions of you. I would be able to make all the arrangements through our local telephone company. I felt that, if you will, you could talk to the students for 20 or 25 minutes and then give them an opportunity to ask you some questions.The total time involved would be 35 to 40 minutes.

This is purely experimental on our part, but I think that it would be thoroughly inspirational to my 130 physics students, who represent one half of our junior class.

If you feel that you could take time out of your busy schedule for such an experiment as this, I would be most happy to communicate with you in more detail at your earliest convenience.Thanking you for your kind consideration, I remain

Sincerely yours,

Thomas J. Ritzinger

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO THOMAS J. RITZINGER, MARCH 15, 1966

Mr.Thomas J. Ritzinger

Rice Lake High School

Rice Lake,Wisconsin

Dear Mr. Ritzinger:

What a wonderful idea! It sounds terribly expensive, but if you say so, it is OK with me.

Anyway, let’s try this grand telephone call. I think it will work best if I do nothing but answer questions for the whole thirty-five to forty minutes. I’ll probably go crazy trying to explain things without a blackboard. But it sounds like fun and I would like to try.

Wednesday and Thursday afternoons and Tuesday mornings are bad for me. Other times are OK except April 2 and April 22-27, when I am going to New York.

A great and original idea that I have never heard of before! (How expensive is it?)

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

On April 25, 1966, Tom Ritzinger wrote to thank Feynman. He said the youngsters “were most excited, and their remarks since our conversation would indicate to me that they gained much from your answers and remarks.”

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO MARY E. HAWKINS, MARCH 21, 1966

National Science Teachers Assoc.

Washington, D.C.

Dear Mrs. Hawkins:

Please do not set up any News Conference for me (as suggested by M. Ruth Broom in her letter of March 7). My only aim is to talk, as requested on “What is Science” on Saturday, April 2, 1966 at your conference. The purpose of the talk is just to discuss the meaning of science with the people attending the conference. I will have nothing of really great value or importance say, as far as I know, and I surely have nothing of interest for the general public. I do not expect any “coverage” of my talk outside of the audience who comes to listen to me.

Since it is an education conference reporters will want to know about educational matters. I know practically nothing about such things, and therefore, do not think it is worthwhile for me to have any news conference. There will be no news.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO MRS. WHITEHOUSE, APRIL 13, 1966

Feynman was no longer officially on the California State Curriculum Commission, but he nonetheless reviewed science textbooks for the commission in 1966.

Mrs.Whitehouse—Here are some notes on Grades 1 & 5 of six series on science.

Scott Foresman—Fair. A spotty mixture of good and poor.

In 1st grade, simple clear experiments on condensation, etc., but most of the stuff on animals is how they differ in superficial ways (nothing on how they grow, eggs, babies, etc.)

In 5th grade, chemistry and sound is good and clear, but material on weather and electricity are not very good. In particular, in both these parts (weather and electricity) the teacher’s manual doesn’t realize the possibilities of correct answers different from the expected ones and the teacher instruction is not enough to enable her to deal with perfectly reasonable deviations from the beaten track. Also, in these sections, difficult experiments are suggested which may not work out easily as expected, but the teacher is not given clues that this might happen or what to do about it.

MacMillan—Good.

First grade is readable and directly understandable. Nice experiments, and a reasonable amount of content. The fifth grade is good science and very real, including many real pictures (not artists’ conceptions) but in my opinion, there is very much too much material.

Laidlaw—Poor, in both grades.

In first grade, much ado about classifying animals by an unsound classification scheme (by fur, wings, hard covers, scales). In teacher’s manual, many confusing or unclear statements. Many questions but no direction or motivation (like why classify the animal). Idea is to get them to say some preconceived thing about living things.

Very many of the “guiding the discovery” questions have answers in the teaching manual that will require a great deal of interpreting and rewording before they can be understood by children. Not enough for the less scientifically trained teacher to go on in the manual to be able to do it herself.

In fifth grade again there is a lack in teacher’s manual. I can rarely read more than one paragraph in the student text without finding something a little mixed up or imprecise (where to say it precisely and correctly is no harder). It appears as though made by a confused mind rather than a clear thinking one. There is not enough in the teacher’s edition to enable the teacher to remedy this lack. Even in the teacher’s edition, a very large part is a little bit wrong.

Heath—Good.

In first grade, simple, correct and good. Not a great deal of stuff. Dealt with straight-forwardly.The teacher’s edition is a good clear science lesson for teachers, putting them much in advance of pupils.

In fifth grade, there is a healthy emphasis on making and calibrating good instruments and doing significant experiments.There is a good, practical viewpoint. But there are so many experiments, so many devices to make, etc. Is it not too much?

Harcourt, Brace & World—Fair.

In first grade an otherwise good text has a very serious weakness that a scientifically minded teacher could remedy, but that a poor teacher would develop happily. In fact, it is the very first lesson which is the most dangerous in this way and everyone can easily start off on the wrong track. I use this first lesson as an example to show what I am worrying about. It begins with a question, “Why does the toy dog move when it is wound up?” A good beginning if we were then to take it apart, see the gear and levers driven by the taunt spring, and see in detail how the thing goes. But the direct question has an obscure and meaningless (to children, and nearly meaningless to me) answer,“Energy makes it move.”This same answer is to be given to the same question about real dogs, motorbikes, etc.

One gets the impression then that science is to be a set of pat formulas to standard questions. “What makes it move,” quickly all hands are eagerly raised, the lesson is learned, they are to say “Energy makes it move,” “Gravity makes it fall,” “The soles of our shoes wear out because of friction.” Just words, nothing is explained. It is like just saying “Because of God’s will” and having nothing left to look into.

Energy in particular, is a very subtle concept, very difficult for first grade to understand (but easy, of course, to learn in a formal, parrot way without understanding). Force is much easier. It is unfortunate that this series starts so poorly.This tendency to try to elicit answers for a certain form from the students occurs in the other parts of the first grade book.

Another, less important weakness, I think, is to use artists’ imaginary pictures as “evidence” of what happened. (For example, on page 34, the teacher’s edition says, “Let them verify their predictions by looking at the fourth picture” etc.). Again, there are no real pictures, for example, of a fossil, and no suggestion is made that a real fossil be brought in.

The fifth grade is good science, rather detailed without many experiments. It seems fine to me if it is not too much.

Harper & Row—Good.

In first grade, seems very good and goes far. The fifth grade is also very good, in particular processes, as well as facts, are dealt with well, and the discussions of how we learn things is good. Possibly too much (see, for example, vocabulary p. 180).

I have noticed quite a few rather serious errors or misleading statements in both grades—but they are isolated, and can be remedied.

(I cannot help adding, unscientifically that my 3 1/2 year old boy has gotten his hands on this set which the company sent me when I was on the Commission. He often asks me to read to him from them. We have done some of the experiments. I considered them very poor books, and felt silly reading some of the things in them. In comparison to other books, and on looking at the teacher’s edition, I realize now Grade 1 and Grade 5 are rather good.

I still feel other grades may have too much of this “we observe, for no good reason.” But I cannot include this as I haven’t seen the other grades for the other sets.

At any rate, be warned that reading only Grade 1 and Grade 5 may not suffice to judge a set of books from 1 to 6.)

Conclusion

There are many good sets. But can I express an unscientific opinion? I believe that some of the best are trying to teach too much science.There are many things in many subjects for children to learn, and the detailed names of the parts of a nerve cell, etc., is really unnecessary in the 5th grade. Science should not overwhelm the other subjects. Too much of a good thing will give everyone indigestion. Also, are we already in danger of a general crisis and collapse from teacher overload?

You ask if I would advise co-basal adoption. If that means a school can select one set or another set, perhaps ok. But I do not think that two sets are necessary in the same class, (except possibly for one copy in a library as reference). My cursory examination did not show serious weaknesses in any of the sets marked “Good” that needs to be supplemented by another point of view of another text. There is a tendency for too much science already; we need no more, except for references. (I assume you don’t get tempted to adopt Laidlaw because of its apparent simplicity and low coverage.) The coverage level is fine, but the material is not covered clearly. Your teachers may think they like it because it is less to teach and seems simple enough, but rote learning from a teacher following that teaching edition is not a useful training in clear thinking, one of the purposes of teaching science.

Is there any way you can recommend not teaching all the stuff in some of those good 5th grade books?

Finally, all the texts assume the existence of a great deal of equipment from snakes, to chicken eggs, to bell wire. How are you going to supply it? I think it is a responsibility for anyone recommending these books to recommend a practical way to help in the supply of adequate experimental materials to go with them.

Wish I can point out detailed errors I happened to notice in the various books.

I am sorry to have not had time to look at Merrill’s “Principles of Science.”

Regards to all my old friends.

Dick Feynman (signed)

Wed. Morning 3:30 A.M.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO RICHARD GODSHALL, MARCH 2, 1966

In a letter of February 19, 1966, Mr. Godshall thanked Feynman for sending his article on “Textbooks for the New Math.” 17Mr. Godshall asked for Feynman’s opinion of SRA’s Greater Cleveland Math Program and said he wanted to buy ten copies of Feynman’s article to present to the principal and others at a school meeting. He also wrote at some length on his concerns about “new math.” One of the examples Mr. Godshall cited was that after three months of SRA and “many days on properties, I asked a top student to tell me about what she was doing. We were on the distributive property of multiplication over addition.

Her comment still rings in my ear, ‘I know what 2 x 2 is but I don’t get all this jazz.’Yes, and how many other students are asking, ‘Why all this jazz?’”

Mr. Richard Godshall

San Jose Christian School

San Jose, California

Dear Mr. Godshall:

I should like to comment on your remarks on the SRA program.They point up the greatest and most serious criticism of much of the “new math” program. It affects teachers’ and parents’ confidence. Students have a resilience and a skill at recognizing “all that jazz” as just “jazz.” It was a child who understood the emperor’s clothes!

I believe that a book should be only an assistance to a good teacher, and not a dictator. Please have confidence in your common sense and protect the children from being intimidated by the unnecessary abstractions and pseudosophistications of the school books. Stay human, and on your pupil’s side.

If you need a trick way to remember the symbols for “greater” or “less than,” just note the symbol > has a wide side (here, on the left where the two lines diverge) and a narrow side (the point).The number on the wide side is bigger than that on the narrow side (9 > 5 and 5 < 9).

I did have a hand in selecting the books and reluctantly settled on SRA despite many faults (the worst of which is the lack of word problems).We had to select something from what was offered and all the others were even worse (hard though that may be to believe!).We recommended some supplementary books to go with SRA to help offset its formal austerity, lack of word problems, etc. to help make a balanced program. At the last minute the state senate decided to save a little money and cut out all supplementary books.

Enclosed are the ten copies you requested.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

DRAFT OF LETTER WRITTEN BY FEYNMAN

It is not known to whom it was written, the date it was written, or whether it was ever sent.

Dear Sir,

Thank you for your criticism of my article on the new textbooks for the elementary grade mathematics.

You are right that I am not an expert on the matters in my essay. I have not tried to write a unit in any subject for these grades, nor do I have a firm grasp of the state of the students’ experiences or the ability of the teachers, etc., etc. The only experimental material I had was the textbooks themselves—all of which I read carefully.

You are quite right when you say that it is impossible to make a critique of a popular article, for such an article is filled with examples which are easily misunderstood.Your letter proves your point; it criticizes one misunderstood point after another. I am not responsible for your misunderstandings —many seem to come from careless reading.

First you deny that mathematics which is used in engineering and science is largely developed before 1920 by giving examples all from before 1920. Next you read “a good deal of the mathematics which is used in physics was not developed by mathematicians alone, but to a large extent by theoretical physicists themselves,” as saying “most applicable mathematics has been invented by non-mathematicians.”“A great deal” is not “most” and certainly not “all.” Your examples only show that not all applicable mathematics was invented by non-mathematicians.

I deny your assertion that I imply that mathematicians are at fault for not concerning themselves with applications. I merely said that pure mathematicians do not concern themselves with applications, and that users of mathematics must pay more attention to the connection between mathematics and the things to which it applies than pure mathematicians are likely to do. Is that not so?

I am not against the abstraction of mathematics—that is what makes it useful. Please read my article again. I do know from very much experience (for example with many mathematically trained writers of articles on quantum mechanics) that abstraction alone is not enough for many practical purposes. It is also (read “also,” not “only”) important to understand the connection of the symbols to what they are applied if mathematics is to be truly useful. I have all these textbooks before me. It is easy to see that 17 amperes and 15 volts will be added together rarely if ever. But what do we do with a textbook which (unlike most of the others) says mathematics is useful in the sciences and then gives the example: “Red stars have a temperature of 8000 degrees, Blue stars, 12000 degrees. John sees three blue stars and one red star.What is the total temperature of the stars John sees? I was so pleased to find a text which tried to give any scientific example of the use of mathematics and so shocked at the example (not just one—all the examples in the section were adding or subtracting temperatures of various colored stars) that you must not blame me for thinking something is wrong with the textbooks offered for adoption of the State of California. Did you read some of these textbooks?

I do not condemn technical words—I object to learning only the words and nothing to say with the words. About “words” and “facts,” I do not object to “words” in my article, only to “words” and no “facts.” Do you not think some facts should come with the words so something about the mathematicians’ words is learned other than only the words the mathematicians use?You may think I exaggerate—but read some of the books—for example on geometry I found hundreds of definitions with only two facts (the facts were a closed figure divides a plane into two regions, and the diagonals of a rectangle are equal). I just think that more semi-intuitive knowledge of geometry might be developed in the considerable time the students were studying it than that. If not, then save the time for another subject in mathematics.

You said,“You denounce the use of any base but 10.”

Freshman—Oh excuse me, I didn’t know you were reading.

Professor—I wasn’t.

Sincerely Yours,

[unsigned]

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO EDWIN H. LAND, MAY 19, 1966

Mr. Edwin H. Land

Polaroid Corporation

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Dear Mr. Land:

I had a great time visiting you and your colleagues (whose names I unfortunately do not remember). The experiments provoked many thoughts, and I’m still thinking. It is too bad I am not at M.I.T., so I could come over and bother you more, for there are several effects which I would like to see again in more detail.There were so many new things that I did not realize until later the relative importance of some of them. I shall write you some of my ruminations, not that you have not already thought of them, and that I am telling you anything new, but rather as a continuing informal conversation to see how well I am learning my lessons.

On the plane I started to think of why the “positive in red, negative in white” gives no color, and I immediately realized there was something else far more fundamental that I did not understand (and this may just be a special case of it). The puzzle is, why, when the regular red and white pictures (giving good color sensation) are slightly offset the color disappears completely over the entire picture. In short, I think I understand (via the retinex view) how to determine the color to be seen, if you see it. But what principle determines the condition under which you do not see it, and why?

The right answer must be determined by experiment and pure speculation has no place—but not being able to experiment I could not keep my mind from wandering on the plane. So I should like to report on my pure speculations just for fun, not in the sense that I think these things are necessarily so, but only for the fun of thinking how exciting it might be.

Our first principle is that the thing is made to live. An animal must recognize a bug as the same bug no matter at what distance, what angle, what illumination, etc. and this is of first importance for the simplest seeing animal. It must sort the clues and interpret them. I mean by “interpret” that it must discover (in some way) some “object concept” which will explain what it sees. If you see (in the primary sense of light on the retina) an ellipse, you must perceive it as a circle inclined in space (if that is what it is) immediately and directly.The “circle inclined in space” or the “bug” etc. are what I mean by “object concepts.” They are really like theories to explain what you are seeing (in the light-on-retina sense). So size constancy shape constancy (e.g., trapezoids or parallelograms seen are perceived as a rectangle in various positions), lightness constancy, color constancy, etc. are all examples of the action of the “interpretation” step in vision.What is illumination gradient, and what is color variation of an object is sorted by this “interpretation”, etc.

I shall call it an “interpreter” although I have no idea of how it works. Our man-made machines are simple, but cannot do this very well.We tend to think that the first stages of vision must be simple and mechanical in this way too. For example, we suppose gadget A measures the mean illumination, controls level of sensitivity of gadget B, which measures intensity at a point, etc., etc., to explain lightness constancy, and an entirely new mechanism to convert binocular discrepancy to distance, and still another to how we determine that a row of dots form a straight line, and another complex imaginary machine for recognizing ellipses as circles, etc., etc. I do not know how any one of them really works. But it is evident that the net result and function of all are qualitatively very similar—so for the time being, perhaps it is very wise just to recognize (1) that it is done, (2) that it is vital to survival of the simplest sensing animal—so it can use its senses to distinguish food from pebbles, (3) there must be many characteristics of this process that are common from one case to another. Therefore, let us study “interpretation” and its characteristics for itself—leaving detailed mechanisms for future study. (I guess what I call “interpretation” must be what psychologists call “forming the gestalt.”)

Therefore your experiments on color vision are of vital psychological importance because they can study this “interpretation” process in an example which is easy to control experimentally and is as little as possible under the influence of conscious effort.

Let us suppose the “method of interpretation” is to supply a theory (or object concept) to explain the clues seen and, if the theory fits all clues, perceives the “vision” as the object, and sends his opinion to the next mental layer above it for a further level of interpretation. I imagine the hierarchy: interesting spots of light; straight lines; rectangles in space; a box lying on the table; Jack’s coffin; tragedy and sadness as some kind of series of “interpretations” on one level after another working up through the levels of the brain.We are studying just one interpreter, that of “colored objects.”

Thus the lights from the Mondrian are perceived as colored objects, for the theory fits perfectly. And if the illumination changes the theory of “colored objects in unusual illumination” still works perfectly and the colors don’t change. Likewise, the red and white superposed pictures produce retinexes for which “colored objects in some illumination” is an adequate theory fitting nearly all the facts (binocular clues, other information changes theory) so one is really aware that there are no objects, and it is only a picture on a screen but they cannot countermand the color interpreter for that is at a lower level, out of voluntary control). But if the pictures are slightly offset, the theory does not work, the “objects” are too complicated, and there are regularities in the double image not explained by it.We no longer see “colored objects.”

Is it unbelievable that a part of the brain can make one do much “thinking”, and interpreting and we would be unaware of it and not be able to control it? Maybe. But maybe not. The simplest animal must be able to think at this kind of level if he sees at all. Is it not conceivable that this marvelous “process of interpretation” once invented by evolution is used over and over again in one layer on top of another as the complexity of the brain evolves? That higher “thinking” is much like lower thinking? That is, that the lower interpreting appears too much like thinking to us.Would it not be advisable to let the lower thinking processes in vision go on automatically out of conscious control for efficiency reasons? It is built in and unlearned in man, just as the whole behavior is built in and little learned by insects and other simple animals.

Physicists looking at psychology, through force of habit, try to suggest some simple element be found to study, rather than the whole human brain at once. Often they have suggested using simple animals but the difficulty is our brain is not hooked to them and we have experimental difficulties in determining “how the world looks to a caterpillar.” But it is possible we have “simple animals” right in our own brain, left relatively intact in evolution, which our higher centers are hooked to, but which are not under easy voluntary control of these higher centers. One of these “simple animals” may well be the “color interpreter.”

Thus I would like to know all you can tell me about when we do and when we do not see the colors. My first guess about interpreters would be two laws: (1) If an “object concept” explains all clues adequately, the scene is interpreted as that “object.” (2) If other strong regularities appear which are not explained by that “object concept,” the interpretation will either not be made, or it will be made from time to time with other interpretations tried from time to time. If an interpretation is not made, the uninterpreted picture is sent up to higher centers (maybe—whatever that means).

I thought of a few other things, less important. First, what physically comes from the screen from each point of one of your red and white projections is various kinds of “pink light” (where by “pink light” I mean light which is the sum of some amount of the white projectors light plus some amount of the red filtered projectors light. “Pink light” can appear green or brown, etc.). Hence a single slide in one projector containing certain red dyes plus gray absorption could imitate it exactly and it would in principle be able to send to all your friends’ quickie demonstrators: one slide that viewed outside the projector by looking through it appears only gray and red, etc. will produce a “full” color projection. (“Full” means as full as your red and white projections appear to be—greens, oranges, brown, reds, etc.)

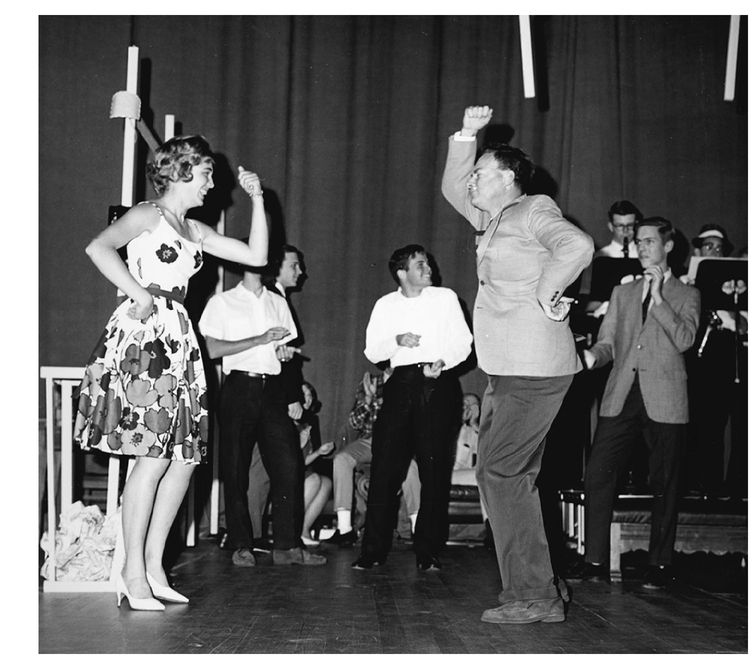

Caltech talent show, 1966.

Second, and this is harder, it should be possible to produce an object, a kind of painting in red and gray, which when placed against a dark velvet background and illuminated by a spot of light (which lights it only, and the rest of the room only indirectly) looks to be in “full” color.

I had other thoughts, but this letter, which I started as soon as I got back, has, through many interruptions, taken me two weeks to write.

The threat still holds, if you do not come here and give talks on your experiments, I shall give them.

Yours Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

TOMAS E. FIRLE TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, AUGUST 7, 1966

Dear Dr. Feynman:

I need to thank you! In an essay a while ago you expressed your thoughts in some paragraphs starting “. . . I stand at the seashore...”

When I first heard these expressions I had an immediate deep response of a good feeling, faith, of beauty. I took the liberty to graphically rearrange your words to make them more expressive to me. Incidentally there are other interesting permutations possible.

On receiving news of my father’s death in Germany last July 4, I wanted to share some feelings of words of creation and life with my stepmother and I found myself attempting a “translation” of your thoughts into German. Since it has been a long time since I left Germany my “translation” is undoubtedly poor, but it conveyed something of my thinking and feelings, as expressed by you, to my stepmother.

Why do I write you this letter? Partly to extend my thanks to you, to tell you that with these, to you maybe unimportant lines, you have filled another human being’s need. Also, frankly, I enjoy the sensitivity of your “thoughts” especially since to me they indicate the closeness of artistic creation with scientific greatness.

Yours truly,

July 7, 1966

I stand at the seashore,

alone, and start to think...

There are the rushing waves...

Mountains... of molecules,

each stupidly minding its own business...

trillions apart....

yet forming white surf in unison.

Ages on ages...

before any eyes could see...

year after year thunderously pounding the shore as now.

For whom, for what?...

on a dead planet,

with no life to entertain.

Never at rest...

tortured by energy

wasted prodigiously by the sun...

poured into space.

A mite makes the sea roar.

Deep in the sea, all molecules

repeat the patterns of one another

till complex new ones are formed.

They make others like themselves...

And a new dance starts.

Growing in size and complexity...

living things,

masses of atoms, DNA, protein...

Dancing a pattern ever more intricate.

Out of the cradle onto the dry land...

Here it is standing...

atoms with consciousness...

matter with curiosity.

Stands at the sea...

wonders at wondering

I. . .

a universe of atoms

an atom in the universe.

Richard P. Feynman, Science and Ideas, edited by A. B. Arons (Prentice-Hall, 1964), p. 5.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO THOMAS E. FIRLE, OCTOBER 4, 1966

Mr.Thomas E. Firle

Del Mar, California

Dear Mr. Firle:

I need to thank you.Thank you for noticing and enjoying what I tried to “hide” in my lecture. Really, I thought of it poetically also, but was afraid of ridicule if I tried to write a poem in a lecture. The rearrangement is almost exactly the way I would have done it. In fact, you should see my hand written lecture notes that I made to guide me as I gave the lecture for the first time—they are written out in lines just as you “deciphered.” Naturally, I am very pleased and flattered that you thought them worth translating to German. But, it means even more to me that you found the thought of some relevance to you in the face of your father’s death.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO R. HOBART ELLIS, JR., OCTOBER 3, 1966

As a reply to a questionnaire from Physics Today, Feynman wrote, “I never read your magazine. I don’t know why it is published, please take me off your mailing list. I don’t want it.” On August 25, 1966, the editor wrote to say that Feynman’s reaction “poses some interesting questions for us.” His main concern was where the magazine had failed. “Is it in the nature of the purpose or in the way we are serving it? . . . If Physics Today is not the magazine physicists want and need, we would like to supply what they do want and need” Here is Feynman’s response.

Mr. R. Hobart Ellis, Jr.

Physics Today

New York, New York

Dear Sir:

I’m not “physicists,” I’m just me. I don’t read your magazine so I don’t know what’s in it. Maybe it’s good, I don’t know. Just don’t send it to me. Please remove my name from the mailing list as requested. What other physicists need or don’t need, want or don’t want has nothing to do with it.

Thank you for spending all the time to write such a long letter to me. It was not my intention to shake your confidence in your magazine—nor to suggest that you stop publication—only that you stop sending one copy here. Can you do that, please?

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

IRWIN L. SHAPIRO TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, OCTOBER 21, 1966

Dear Professor Feynman:

I thought you might be amused to know that after a film of your superb lecture on the “Great Conservation Principles” was shown here last week several in the audience were overheard proposing that you run for governor. It was not clear, however, whether the intention was for you to be a candidate in California or here in Massachusetts.

Sincerely yours,

Irwin L. Shapiro

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO IRWIN L. SHAPIRO, DECEMBER 6, 1966

Professor I. L. Shapiro

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Lincoln Laboratory

Lexington, Massachusetts

Dear Professor Shapiro:

They were, of course, speaking of California. At this time I feel it is better to issue releases denying an interest but not completely dashing the hopes of those working at the grass roots. At the appropriate time, I shall announce my reluctance but pleasure in accepting the responsibilities urged upon me by my constituents. Until then, please make no public statement, although privately you may feel free to give a word of encouragement and hope to those who are working hardest on my behalf.

Thank you for your report on conditions in Massachusetts. Please be assured that I shall not forget my good friend, Irwin Shapiro, when I am in a position to help you more directly.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO MIKE FLASAR, NOVEMBER 9, 1966

Mr. Mike Flasar

Boston, Massachusetts

Dear Sir:

The information you have about the number and need for theoretical and experimental physicists is quite correct.The B in mathematics is of no consequence, as that kind of mathematics, although popular, is not really necessary in physics, theoretical or experimental.

Work hard to find something that fascinates you.When you find it you will know your lifework.A man may be digging a ditch for someone else, or because he is forced to, or is stupid—such a man is “toolish”—but another working even harder may not be recognized as different by the bystanders—but he may be digging for treasure. So dig for treasure and when you find it you will know what to do. In the meantime, you don’t need to make the decision—steer your practical affairs so the alternatives remain open to you.

In any of the graduate schools you mentioned there is always the opportunity to change from theory to experimental or vice versa at any time.

While looking for what fascinates you, don’t entirely neglect the possibility that it may be found outside of physics.The man happy in his work is not the narrow specialist, nor the well-rounded man, but the man who is doing what he loves to do.You must fall in love with some activity.

Yours sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO JEHIEL S. DAVIS, DECEMBER 6, 1966

Mr. Jehiel S. Davis

Van Nuys, California

Dear Sir:

I am sorry, but I have no information regarding the color television used at the Chicago Worlds Fair in 1922 nor do I know who to refer you to for this information.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO ASHOK ARORA, JANUARY 4, 1967

Master Ashok Arora

Debra Dun (U.P.) India

Dear Master Arora:

Your discussion of atomic forces shows that you have read entirely too much beyond your understanding.What we are talking about is real and at hand: Nature. Learn by trying to understand simple things in terms of other ideas—always honestly and directly. What keeps the clouds up, why can’t I see stars in the daytime, why do colors appear on oily water, what makes the lines on the surface of water being poured from a pitcher, why does a hanging lamp swing back and forth—and all the innumerable little things you see all around you. Then when you have learned to explain simpler things, so you have learned what an explanation really is, you can then go on to more subtle questions.

Do not read so much, look about you and think of what you see there. I have requested the proper office to send you information about Caltech and the availability of scholarships.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO TORD PRAMBERG, JANUARY 4, 1967

Mr.Tord Pramberg

Stockholm, Sweden

Dear Sir:

The fact that I beat a drum has nothing to do with the fact that I do theoretical physics. Theoretical physics is a human endeavor, one of the higher developments of human beings—and this perpetual desire to prove that people who do it are human by showing that they do other things that a few other humans do (like playing bongo drums) is insulting to me.

I am human enough to tell you to go to hell.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

A. R. HIBBS TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, JANUARY 10, 1967

Dr. Albert Hibbs was a graduate student of Feynman’s, a co-author (of Quantum Mechanics and Path Integrals), and a very close friend. He held many positions at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory over the years, but he was best known as the “voice of JPL,” for his work as a broadcast spokesman for many of its planetary missions. (Incidentally, my husband and I were married at his home; Dr. Hibbs performed the ceremony, as he was an ordained minister—by mail—of the Church of the Mother Earth.)

Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Interoffice Memo

Subject: Application for Astronaut

Here is the reference form which I have spoken to you about. My application as an astronaut is made with considerable optimism. I am both over-age and over-height. Nevertheless, I am counting on the phrase which the National Academy has used in describing these limitations: “Exceptions to these requirements will be allowed in outstanding cases.” Obviously, I have to represent myself as outstanding in some particular area. I have a good background in both space science and particularly in space instrument systems.The broadness of this background may be unique, but this may not be too important for the Apollo Project. Nevertheless, I am counting on the desire on the part of the Academy and NASA to find what they term,“astute and imaginative observers,” and I hope that my background qualifies me in this area.

But I think the one field where I might be called exceptional is my experience in communicating scientific results to others. So it is as a combined observer and communicator that I hope to present myself as an exceptional case.

Thank you in advance for your help.

—Al

BETTE BRENT TO THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, JANUARY 25, 1967

Scientist as Astronaut

National Academy of Sciences

National Research Council

Washington, D.C.

Dear Sir:

I am attaching a Confidential Reference Report for Albert Roach Hibbs as completed by Professor Richard P. Feynman of Caltech.

I have taken the liberty of typing Professor Feynman’s comments for easier reading for S-1, D-8, D-9 and D-10.

Sincerely yours,

(Miss) Bette Brent

Secretary to Richard P. Feynman

Comments and Summary

Applicant: HIBBS, Albert Roach

S-1

Hibbs’ only weakness is that he is not a very highly-trained specialist in some particular scientific corner. For your needs this should prove an advantage—for his scientific understanding and spirit is ideal—just what is needed to study unexpected phenomena. Too much training, say in geology, could lead to expecting features on the moon like those on the earth—whereas a more open but extremely careful and observant mind (as Hibbs has) would see more clearly what is really there. His general calmness, yet deep and wide scientific attitude and interest make him an ideal observer. Finally, do not forget the wide experience in explaining science on TV and radio—how well he will be able to tell the world what he has seen, what it means and what the entire lunar program means.

Personal Characteristics

D-8

No opportunity to observe. Knowing the man I would guess that he would remain unusually clear and observant—he always is—he takes his scientific spirit of observation into all his experiences and he seeks out unusual experiences.

D-9

He has done a great deal of exposition both very technical (we wrote a book together) and to non-technical audiences on TV and radio and is very good at it—always maintains his good sense and wisdom about what is important.

D-10

He has had many positions of responsibility and leadership and I have not heard of any “personality difficulties” in the jobs he has had—although I do not have first-hand information from his colleagues and workers below him in more than two or three cases. I have worked with him intimately without anything but pleasure.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO GEORGE W. BEADLE, JANUARY 16, 1967

Dr. George W. Beadle

The University of Chicago

Office of the President

Chicago, Illinois

Dear George,

Yours is the first honorary degree that I have been offered, and I thank you for considering me for such an honor.

However, I remember the work I did to get a real degree at Princeton and the guys on the same platform receiving honorary degrees without work—and felt an “honorary degree” was a debasement of the idea of a “degree which confirms certain work has been accomplished.” It is like giving an “honorary electricians license.” I swore then that if by chance I was ever offered one I would not accept it.

Now at last (twenty-five years later) you have given me a chance to carry out my vow.

So thank you, but I do not wish to accept the honorary degree you offered. Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO TINA LEVITAN, JANUARY 18, 1967

Tina Levitan wrote to Feynman requesting a biographical sketch and a black and white photograph for inclusion in her book-in-progress, The Laureates: Jewish Winners of the Nobel Prize.

Miss Tina Levitan

New York, New York

Dear Miss Levitan:

It would not be appropriate to include me in “Jewish Winners of the Nobel Prize” for several reasons, one of which is that at the age of thirteen I was converted to non-Jewish religious views.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

TINA LEVITAN TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, JANUARY 30, 1967

Dear Dr. Feynman,

Your letter of January 18, in which you state that it would not be appropriate for me to include you in my book of Jewish Winners of the Nobel Prize, has been received.

My listing of Jewish Nobel Prize winners includes not only professing Jews and those partly of Jewish ancestry but also those of Jewish origins for the simple reason that they usually have inherited their valuable heredity elements and talents from their people.

Under these circumstances may I include you? I will not represent the fact that at the age of thirteen you were converted to non-Jewish religious views.

If there is another reason why you do not wish to be included, please let me know.

Sincerely yours,

Tina Levitan

(Miss) Tina Levitan

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO TINA LEVITAN, FEBRUARY 7, 1967

Dear Miss Levitan:

In your letter you express the theory that people of Jewish origin have inherited their valuable hereditary elements from their people. It is quite certain that many things are inherited but it is evil and dangerous to maintain, in these days of little knowledge of these matters, that there is a true Jewish race or specific Jewish hereditary character. Many races as well as cultural influences of men of all kinds have mixed into any man. To select, for approbation the peculiar elements that come from some supposedly Jewish heredity is to open the door to all kinds of nonsense on racial theory.

Such theoretical views were used by Hitler. Surely you cannot maintain on the one hand that certain valuable elements can be inherited from the “Jewish people,” and deny that other elements which other people may find annoying or worse are not inherited by these same “people.” Nor could you then deny that elements that others would consider valuable could be the main virtue of an “Aryan” inheritance.

It is the lesson of the last war not to think of people as having special inherited attributes simply because they are born from particular parents, but to try to teach these “valuable” elements to all men because all men can learn, no matter what their race.

It is the combination of characteristics of the culture of any father and his father plus the learning and ideas and influences of people of all races and backgrounds which make me what I am, good or bad. I appreciate the valuable (and the negative) elements of my background but I feel it to be bad taste and an insult to other peoples to call attention in any direct way to that one element in my composition.

At almost thirteen I dropped out of Sunday school just before confirmation because of differences in religious views but mainly because I suddenly saw that the picture of Jewish history that we were learning, of a marvelous and talented people surrounded by dull and evil strangers was far from the truth.The error of anti-Semitism is not that the Jews are not really bad after all, but that evil, stupidity and grossness is not a monopoly of the Jewish people but a universal characteristic of mankind in general. Most non-Jewish people in America today have understood that. The error of pro-Semitism is not that the Jewish people or Jewish heritage is not really good, but rather the error is that intelligence, good will, and kindness is not, thank God, a monopoly of the Jewish people but a universal characteristic of mankind in general.

Therefore you see at thirteen I was not only converted to other religious views but I also stopped believing that the Jewish people are in any way “the chosen people.” This is my other reason for requesting not to be included in your work.

I am expecting that you will respect my wishes.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO TINA LEVITAN, FEBRUARY 16, 1968

Miss Levitan wrote on February 16, 1967, agreeing to respect his wishes and not include him in her book. One year later she informed Feynman he was again under consideration, this time for an article on “The Scientist and Religion”—“a portrait gallery of Jewish scientists of great intelligence and creative accomplishment.” She enclosed a questionnaire and asked for a photograph.

Dear Miss Levitan:

I have your form letter and questionnaire of February 14. Please see my previous correspondence, in particular, my letter of February 7, 1967, to understand why I do not wish to cooperate with you, in your new adventure in prejudice.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO JAMES D. WATSON, FEBRUARY 10, 1967

Early in 1967, while both visiting the University of Chicago, James Watson gave Feynman a copy of the manuscript for the book that would later be published as The Double Helix. They had met when Watson visited Caltech to give lectures on the coding systems of DNA. The following letter was Feynman’s reaction.

Don’t let anybody criticize that book who hasn’t read it thru to the end. Its apparent minor faults and petty gossipy incidents fall into place as deeply meaningful and vitally necessary to your work (the book—the literary work I mean) as one comes to the end. From the irregular trivia of ordinary life mixed with a bit of scientific doodling and failure, to the intense dramatic concentration as one closes in on the truth and the final elation (plus with gradually decreasing frequency, the sudden sharp pangs of doubt)—that is how science is done. I recognize my own experiences with discovery beautifully (and perhaps for the first time!) described as the book nears its close.There it is utterly accurate.

And the entire ‘novel’ has a master plot and a deep unanswered human question at the end: Is the sudden transformation of all the relevant scientific characters from petty people to great and selfless men because they see together a beautiful corner of nature unveiled and forget themselves in the presence of the wonder? Or is it because our writer suddenly sees all his characters in a new and generous light because he has achieved success and confidence in his work, and himself?

Don’t try to resolve it. Leave it that way. Publish with as little change as possible. The people who say “that is not how science is done” are wrong. In the early parts you describe the impression by one nervous young man imputing motives (possibly entirely erroneous) on how the science is done by the men around him. (I myself have not had the kind of experiences with my colleagues to lead me to think their motives were often like those you describe—I think you may be wrong—but I don’t know the individuals you knew—but no matter, you describe your impressions as a young man.) But when you describe what went on in your head as the truth haltingly staggers upon you and passes on, finally fully recognized, you are describing how science is done. I know, for I have had the same beautiful and frightening experience.

If you were really serious about wanting something on the flyleaf, tell me and we can work something out.

The hard cover edition of Watson’s book does indeed have a quote from Feynman on the dust jacket: “He has described admirably how it feels to have that frightening and beautiful experience of making a great scientific discovery.”

DANNY ROBINSON TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, FEBRUARY 13, 1967

Dear Sir,

I am in the sixth grade and my name is Danny Robinson. In class my teacher was reading to us about microminiaturization. The book was from Life and it was called The Scientist. In the book it said that you offered $1,000 of your own money to anyone who could build you an electronic motor that is no more than a quarter millionth of a cubic inch in volume. In the book it said a man made one. Is it true? If it is true could you tell us what kind of tools the man used? What is the purpose for it? How did it work out? How long did it take him to build it? Where do you keep it?

I thank you very much for reading my letter and will you please write back to—.

Thank you,

Danny Robinson

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO DANNY ROBINSON, FEBRUARY 24, 1967

Mr. Danny Robinson

Petaluma, California

Dear Mr. Robinson:

You are right—there is such a motor as you described. It was made by a Mr. McLellan in response to a challenge I made in a lecture. I am enclosing a copy of my original lecture, and a description and photographs of the motor and its parts made by Mr. McLellan.

Several motors were made—I have one, there is one in an exhibit case here at Caltech and Mr. McLellan has several.They all still work very well.

There is no use to it—it was all done just for fun. And if you read the lecture carefully you will see that there is another prize offered for small writing, which has not yet been won.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO ARON M. MATHIEU, FEBRUARY 17, 1967

Mr. Aron M. Mathieu, Publisher

Research and Development

Cincinnati, Ohio

Dear Sir:

My doctor forbids me to serve as a consulting editor because it is bad for my blood pressure. I end up wanting to write the book and am frustrated by the actual author.

Enclosed find $25.00 draft sent to me by some nut wanting to throw money away. Buy your wife some flowers with it.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

P.S. The outline you sent me shows no imagination, it is hard to believe that anything very good can come from it.

P.P.S. I am returning the two chapters which you sent in subsequent letters. I have had no opportunity to look at them.

R.B.S. MANIAN TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, MARCH 6, 1967

To,

Dr. Feynman,

Blazer of new trails,

Sir,

It would seem to you most inappropriate and ludicrous to receive a missive (or a missile!) from a nobody like me. I am post-graduate student in physics and came across your “Lectures in Physics” series. When I went through the forward I was staggered. Physics is an elixir no doubt but to ram it in one measure down the throat is entirely another thing. All these diverse facets translate past (as the armoury does on Red Square) your brain swiftly. After the vistas melt it is only a daze felt in a maze.You don’t quite get what I am up to in one stroke: It is too much for the freshman or the sophomore. A great hullabaloo and tom tomming by Physics Revision Committee has not made things all right. I hear that most of the students take it on the lam after some months of turmoil. If things go on like this Caltech cannot produce scholars. One cannot or should not bite more than he can chew. Physics should be stagger-tuned, i.e. given in successive slabs so that student can lap it up steadily. Even if a dog drinks water in a river, it can force it in minute quantities.Your vol. II, III, IV we do in our post graduate curriculum.

Even electro dynamic books by such well-known persons like “Reitz and Milford” and Tralli men are for graduate course as mentioned in their forward. Matrix formulations, tensions, group theory, operational calculus are not for sophomores.You may now well be in the process of retrospection and a sentiment of guilt would have been left after thoughts evaporate. Not even a beaver like you should be eager to introduce reforms that are short-sighted.Your books are no doubt superb but it is a square block in a round hole. Really, inclined planes may be obsolete but they are stepping stones to more refined topics. A climb to the rotunda needs stairs or a lift: one cannot be at the top of Empire State Building pronto. How did you become like this. Not by high-faluting modern way of teaching physics.You did your climb in orderly way. If my views are myopic or I am derived from Conservative forces, please enlighten me.Take me also in the bandwagon and let me get inured to the kaleidoscope of ever changing patterns.

Please Reply.

I believe in your rectitude and bonhomie.

Yours Sincerely,

R.B.S. Manian

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO R.B.S. MANIAN, MARCH 14, 1967

R.B.S. Manian

Bombay, India

Dear Sir:

I think you may be quite right in your criticism. On the other hand, it is equally wrong to insist that all students go up by slow and easy steps along the same route. All students are different, to some one way applies, to others, another. If you do not like my book because it is too advanced for one reason or another, there are many more elementary books than mine. Possibly in your case there is one much more useful to you.

If the school at which you are learning has chosen my book for the Freshman and Sophomore courses, criticize them, not me. The thing I was trying to do when we started these lectures was to teach the students that I had when I gave the lectures.The decision to edit and publish these lectures and to use them in the ensuing years was not made by me. I am proud of these books as Physics books, but on the problem of when to use them, by whom, and where, I have no opinion.

Thank you very much for your remarks. If you need this letter to help you influence the school not to use the books by the elementary students, please do so. Good luck in your venture.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO BERYL S. COCHRAN, APRIL 27, 1967

Mrs. Beryl S. Cochran

Madison Project

Weston, Connecticut

Dear Mrs. Cochran:

As I get more experience I realize that I know nothing whatsoever as to how to teach children arithmetic. I did write some things before I reached my present state of wisdom. Perhaps the references you heard came from the article which I enclose.

At present, however, I do not know whether I agree with my past self or not.

Wishy-washy.

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO HUGH DEGARIS, APRIL 27, 1967

Mr. DeGaris, a second-year physics, math, and philosophy student, said he would like to take over Feynman’s work when Feynman was “too old.” Mr. DeGaris was concerned about losing half his productive years to learning instead of creation and thought perhaps Caltech would be a more conducive atmosphere than the one he was in. He agreed with Murray Gell-Mann’s position on unified field theory—“the greatest adventure of our time”—and said he would like to be “in it” as well.

Mr. Hugh DeGaris

c/o Queens College

Victoria, Australia

Dear Mr. DeGaris:

If you want to be “in it” it doesn’t make any difference where you are. You must learn to develop and evaluate your own ideas. To start with, why not choose your ideas of fractional dimensions, as a purely mathematical idea, and develop it.You are bound to learn something. If it is no good or gets wound up in uninteresting things (which is nearly impossible) you must find another of your own ideas and work that out.

At the same time study physics in the conventional way in schools or through books or encyclopedias.That may give you other ideas—but you need to know something about the problems in physics you are trying to solve (so that you can judge how likely it is that “perhaps he ties up with this idea somehow” etc.).

There is no quick shortcut that I know.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

MARGARET GARDINER TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, MAY 6, 1967

Dear Professor Feynman,

I very much hope that you will agree to sign the enclosed statement which it is proposed to publish as an advertisement in the (London) Times, and if funds reach that far, in one of the more popular, high-circulation papers as well. I am looking for the signatures of a smallish number—around 50—of eminent Americans whose names are also well known in this country (not always overlapping categories). Among those who have already signed are Naum Gabo, Joseph Heller, Professor Stuart Hughs, Thomas Merton, Professor Anatol Rapoport, Professor Meyer Schapiro, William Schirer and Professor Victor Weisskopf. I am hoping to get a number of signatures of those whose names are not yet publicly linked with this protest—or at least, not in this country.

We believe that this advertisement could have a significant effect on public opinion here, where protests about our Government’s support of the war are constantly met with taunts—both official and unofficial—of anti-Americanism and ‘it’s all Hanoi’s Fault’. We also believe that since Britain is the only major power that explicitly supports the war, even a partial disassociation on the part of our Government might be of importance.

I propose to publish the advertisement on June 1st or 2nd, when Parliament is sitting again and while Mr. Wilson is visiting Mr. Johnson. So if you agree to sign, as I hope you will, I’d be grateful for an early reply.

Yours Sincerely,

Margaret Gardiner

London, England

Should you wish to contribute towards the cost of this advertisement please will you make your cheque out to “Gardiner and Kustow—Vietnam Account.”

STATEMENT TO BE PUBLISHED AS AN ADVERTISEMENT IN THE (LONDON) TIMES and to be signed by eminent Americans who are also well known in Great Britain.

We, citizens of the United States, who are deeply concerned over the war in Vietnam, wish to put it on record that we do not subscribe to the official view of our country and of yours, that Hanoi alone blocks the path to negotiations. On the contrary, there is considerable evidence which has been presented to our Government but which has never been answered by them, to show that escalation of the war by the United States has repeatedly destroyed the possibilities for negotiations.

We assure you that any expression of your horror of this shameful war—a war which is destroying those very values it claims to uphold—ought not to be regarded as anti-American but, rather, as support for that American which we love and of which we are proud.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO MARGARET GARDINER, MAY 15, 1967

Miss Margaret Gardiner

London, England

Dear Miss Gardiner:

I would like to sign your letter for I am completely in sympathy with its spirit and its last paragraph. However, I am, unfortunately not familiar with the evidence that escalation has destroyed the possibilities for negotiation. Certainly escalation has failed in its attempt to “force” Hanoi to negotiate—but I have not been following things closely enough to know that there would have been any real possibility of negotiation without escalation. It has seemed to me that Hanoi’s policy has never included such an alternative—but that that is no justification for our being there and destroying what we claim to wish to save.

I feel unhappy that I am not sure enough of my position to be able to sign your letter. As next best alternative I am enclosing a small check to help to make sure your advertisement is published.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO DONALD H. DENECK, JUNE 27, 1967

Whether in response to a letter or phone call is unclear, but on June 13, 1967, a physics editor at a New York publisher wrote Feynman to apologize for any misunderstanding concerning a promotional letter sent his way. “Although the letter may have looked unique, it is just another example of the advanced state of a part of the graphics industry. Briefly, the letter was a precise duplicate of other letters in a mass mailing to something over 3,000 physics professors in the country.” He hoped it had not caused Feynman any embarrassment or offense.

Donald H. Deneck

John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

New York, New York

Dear Sir,

You have me all wrong—I am just trying to cut down on the amount of mail I get. It has nothing to do with being an author, or being embarrassed. I am trying to get off mailing lists.Won’t you please take my name out of your mailing lists? I ask this of all publishers, including Addison-Wesley. Thank you. No offense meant.

Yours sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO MARK KAC, OCTOBER 3, 1967

Professor Mark Kac

The Rockefeller University

New York, New York

Dear Kac,

I’m sorry, but I don’t want to go anywhere to give lectures. I like it here and I want to work in peace and quiet—preparing, going, lecturing, and returning is too much of a disturbance to my tranquil life.

Thanks for the invitation, though.

Yours,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO THE NEW YORK TIMES MAGAZINE, OCTOBER 1967

To the Editor:

It was fun to see my name and my dog’s picture in

The New York Times Magazine (“Two Men in Search of the Quark,” Oct. 8).

18 Although I did do many of the things described in your article, I am really not one of the men responsible for starting scientists thinking about quarks. It was the result of one of the great ideas that Gell-Mann gets when he is working separately.

Richard P. Feynman

California Institute of Technology

Pasadena, Calif.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO MRS. ROBERT WEINER, OCTOBER 24, 1967

As a response to some remarks he made in the Los Angeles Times

on the subject of modern poetry, Mrs. Robert Weiner wrote to Feynman. She felt that Feynman’s remarks “added up to a complaint that modern poets show no interest in modern physics. . .The truth of the matter is that modern poets write about practically everything, including interstellar spaces, the red shift, and quasars.” Concluding that Feynman had a reputation “for liking forbidding difficult stuff,” she enclosed a copy of W. H. Auden’s “After Reading a Child’s Guide to Modern Physics”:

If all a top physicist knows

About the Truth be true,

Then, for all the so-and-so’s,

Futility and grime,

Our common world contains,

We have a better time

Than the Greater Nebulae do,

Or the atoms in our brains.

Marriage is rarely bliss

But, surely it would be worse

As particles to pelt

At thousands of miles per sec

About a universe

In which a lover’s kiss

Would either not be felt

Or break the loved one’s neck.

Though the face at which I stare

While shaving it be cruel

For, year after year, it repels

An aging suitor, it has,

Thank God, sufficient mass

To be altogether there,

Not an indeterminate gruel

Which is partly somewhere else.

Our eyes prefer the suppose

That a habitable place

Has a geocentric view,

That architects enclose

A quiet Euclidean space:

Exploded myths—but who