1970-1975

Feynman’s ongoing emphasis on education brought him the American Association of Physics Teachers Oersted Medal in 1972. It was a distinction that he shared with many of his correspondents over the years: Hans Bethe, J. W. Buchta, Freeman Dyson, David L. Goodstein, Philip Morrison, Frank Oppenheimer, Isidor Rabi,Victor Weisskopf, John Wheeler, and Jerrold R. Zacharias. The following year he received the Niels Bohr International Gold Medal as well.

His physics work at this time consisted of the development of an important concept of partons (that is, asymptotically free quarks), which is still used today. More lectures were turned into highly specialized textbooks (Statistical Mechanics: A Set of Lectures and Photon Hadron Interactions), and Feynman continued work with relativistic quarks. He became increasingly intrigued by computers, and in 1973, he began discussions with Edward Fredkin at MIT about the possibilities of “artificial intelligence.”

Interestingly, and perhaps not surprising given the tumultuous times, many of the people who wrote to him during this period wanted to engage him in political issues. Among the defenses of his decision to work on the atomic bomb and his comments about women’s capacity for science are a number of profoundly affectionate and candid letters.

MEMO TO DELEGATES, MAY 1, 1970

| TO: | Delegates to the XVth International Conference on High Energy Physics |

| FROM: | Henry Abarbanel, Princeton University |

| SUBJECT: | Political Exclusion of Delegates from International Conferences in the Soviet Union |

As many of you are aware, since June, 1967 the Soviet Union has made it a practice to exclude from International Conferences held within its borders delegates from Israel.The method of exclusion has been to invite the delegates then to refuse to grant them visas. Since the exclusion of any group from a scholarly conference for clearly political reasons is intolerable, I propose we act in the following manner in an attempt to avoid such an occurrence at our meeting.

Send a petition (see below) to the Soviet scientists organizing the conference, to the Soviet Academy of Sciences and to the Soviet Foreign Ministry saying, in essence, that the undersigned will refuse to attend the Kiev meeting if any group is excluded for political reasons. Since the Israeli delegation has requested that the visas be delivered by 1 June 1970, the petition will be sent to the Soviets after that date, if it is necessary. If you agree with the basic idea, then please return the signed copy of the petition attached, along with an address where I can contact you during the month of August, 1970, especially during the week before the conference. I will see to it that those interested receive, at least 72 hours before the start of the meeting, notification at the given address whether or not the Israelis or any other group have been refused visas. At that point any action you take with that knowledge is up to you.Timing is an important problem since it usually takes some time for anyone to receive a visa from the Soviets, and it may arrive only weeks or days before departure even when they want you.

Let me say that I would be pleased to accept suggestions on the implementation of this idea and sincerely hope nothing like this will need to be done. It is clearly better to be prepared, however, thus I write you this note.

A copy of this petition along with the names of all delegates to the Kiev Conference who signed it will be forwarded to the Organizing Committee, the Soviet Academy of Sciences, and the Soviet Foreign Ministry. Please return this by May 25, 1970. If you have passed your invitation on to another physicist, could you please pass this note along too. Thank you.

The undersigned invited delegate to the XVth International Conference of High Energy Physics support the idea of a meeting open to all physicists. We will refuse to attend this Conference if it becomes known that any group has been selectively excluded from attendance for clearly political reasons.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO HENRY ABARBANEL, MAY 14, 1970

Dr. Henry Abarbanel

Physics Department

Princeton University

Princeton, New Jersey

Dear Dr. Abarbanel:

I already refused to go to many conferences in Russia, including the Kiev conference. I do not visit Russia for scientific purposes because of its government’s policies maintaining the right to control which of its own scientists go where and do what, scientifically. I agree with your petition but cannot sign it implying I would go if this Israeli thing is fixed up, for I won’t go, feeling the disease is worse than this one symptom.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO K. A. CARDY, AUGUST 27, 1970

A member of the Royal Society UNESCO (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization) Committee proposed to nominate Feynman for the Kalinga Prize for the Popularization of Science.

Mr. K. A. Cardy

National Commission for the United Kingdom

London, England

Dear Sir:

I was honored to hear that you would consider me for nomination for this year’s Kalinga Prize for the popularization of science. I am sorry that I don’t consider myself fit for the Prize. Much as I might be tempted by the proffered trip to India, I don’t feel I could discharge the responsibility to interpret Indian science upon my return.

I am sorry to be so late in answering you, but I was on vacation when your letter arrived and have only just become aware of it.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

JOHN SIMON GUGGENHEIM MEMORIAL FOUNDATION CONFIDENTIAL REPORT ON CANDIDATE FOR FELLOWSHIP, MURRAY GELL-MANN, DECEMBER 9, 1970

Requested of:

Mr. Richard P. Feynman

Report:

There is almost no theoretical discovery in the field of high energy physics that does not carry Gell-Mann’s name.Virtually all that we know of the symmetry of these particles is a direct result of his work.You could not contribute to the development of physics in a more important and more certainly fruitful way than to help this candidate to do whatever he needs to do. It would be a credit to your foundation to accept his request.

Signed Richard Feynman

Whether Feynman’s letter had anything to do with it or not, Dr. Gell-Mann received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1971.

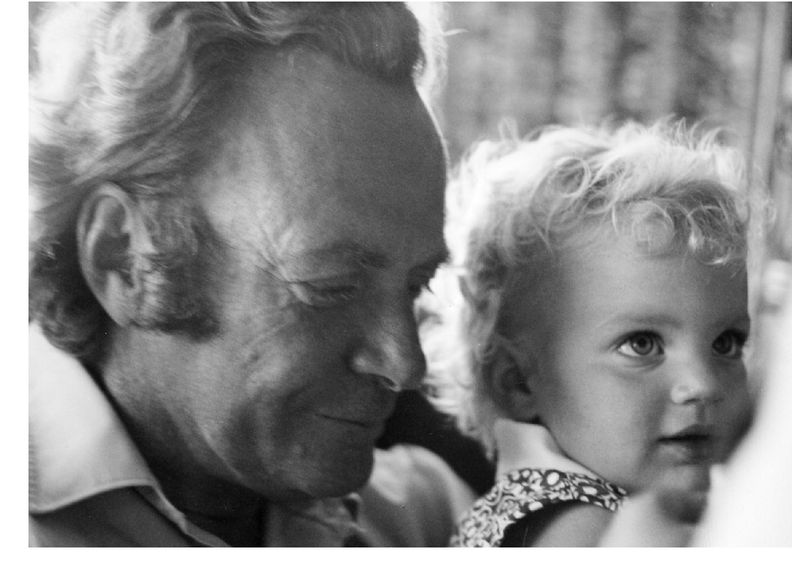

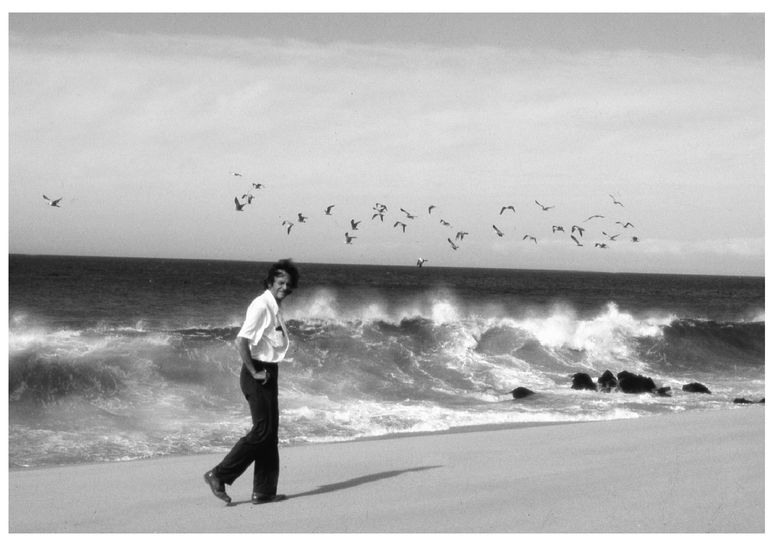

Richard and Michelle, 1970.

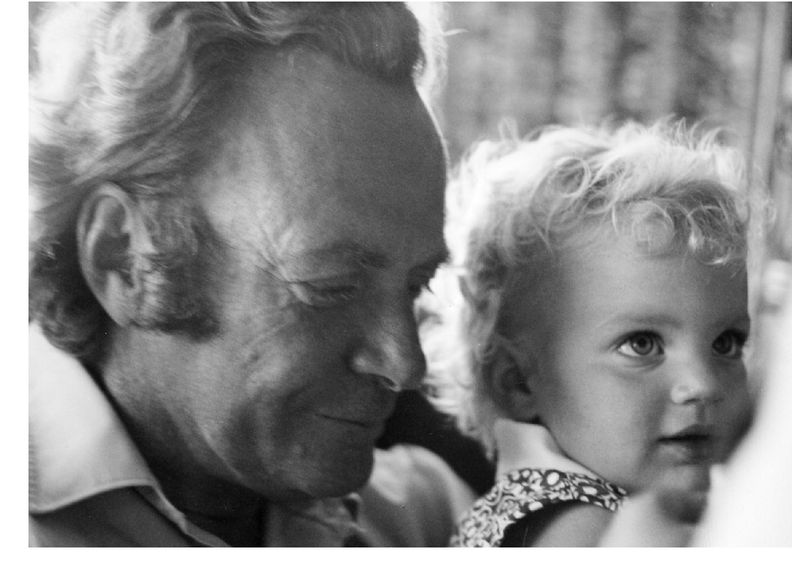

Feynman giving a talk at Argonne National Laboratory, 1970.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO STANISTOW KRUK, JANUARY 18, 1972

Mr. Stanistow Kruk, an eighteen-year-old from Poland, wrote to Feynman, asking, “What is your attitude with respect to the world of science? How did you make your great scientific career? What are your ideas on the still unknown laws of physics? . . .When you were 18 as I am now, did you know what a great future you had before you?”

Mr. Stanistow Kruk

Kielce, Poland

Dear Mr. Kruk:

I am sorry but your questions are too big to be given brief answers. I can only refer you to my lectures published in English called The Character of Physical Law. Lectures more detailed in physics published in Polish are “Wyklady Feynmana Z Fizyki, Warszawa 1970, Panstwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe,” but these you may have already seen.

When I was 18 I did not know what the future might bring, but I did know that I must be a scientist, that it was exciting, interesting and important.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

DR. VERA KISTIAKOWSKY TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, FEBRUARY 11, 1972

Dear Professor Feynman:

I would like to comment briefly on the remarks concerning women that you made at the recent A.P.S. meeting and the criticism of the anecdotes in your book. I have just finished writing a report as chairwoman of the A.P.S. Committee on Women in Physics and, therefore, these are very live issues for me.

Your statement to the effect that women have been discriminated against and that this is ridiculous, was enormously helpful, especially since it was made to an audience containing so many physics teachers. It was also unusual. Although most physicists pay lip service to equal treatment for equal ability and performance, they dismiss existing inequalities as the results of the problems of matrimony and motherhood. Even statistics showing that married women are somewhat more successful than single women are dismissed, because “there are so many factors involved.” Therefore, if your prestige gains acceptance for your statement, you definitely are in line for the Elizabeth Cady Stanton medal.

20However, I must disagree that concern about the anecdotes in your book is energy wasted over trifles. I say this although I have used the book as a text with real pleasure and no twitch of the feminist subconscious. This was several years ago before I started reading and thinking in any coherent way about women’s problems. Since then, my observations of my own reactions and those of my daughter support the results appearing in many psychological and sociological studies—that all the media and most socialization push the female toward a lowered opinion of her capabilities and toward a very ambivalent feeling concerning success.Very briefly, then, let me suggest what might be the subconscious effects of anecdotes such as yours: Feynman (the great physicist) portrays women as less intelligent and not as members of the set containing physicists; I am a girl; maybe I really am excluded from being a physicist. This is possibly an over-simplification, but I think it has a lot of truth in it. Try replacing “woman” by “negro” in those anecdotes to get the flavor.The fact that you are famous greatly heightens the effect. Therefore, I don’t think this is trivial, it is more at the heart of the problem than equal treatment for Ph. D. women physicists.

Very sincerely yours,

Vera Kistiakowsky

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Cambridge, Massachusetts

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO VERA KISTIAKOWSKY, FEBRUARY 14, 1972

Dear Dr. Kistiakowsky:

Thank you very much for your letter. It is true that the quotations in my book are unfortunate and with the increasing sensitivities of today, I probably would have been more careful and not made them. Actually, however, I agree with my sister that in a way they are trivial unless they are missed. “Feynman portrays women as less intelligent and not as members of the set containing physicists” may be a subconscious conclusion but not a fair one (in particular the latter half). Although there was a lady driver and “the changing of a woman’s mind” as two phrases in the vast book there is also “a very ingenious mother” and the “experiments of Miss Wu of Columbia” to offset the impressions (the true tale about the girl friend of the nuclear physicist is about one particular individual, not about women in general).

My sister’s point is that physics is a difficult subject requiring objective thinking and staying on the subject without distraction by minor subsidiary things. She thinks that someone who is so easily put off when considering the subtleties of definition of velocity, or of universality of ability to measure, as to be seriously concerned with the illustrations incidentally used will have a hard time with physics anyway.

She may be wrong. But I am inclined to agree that we should all try to be more rational and attempt to see what is really there and control our subconscious if it is drawing exaggerated conclusions. There is enough problem in what is real.

As you say, you, yourself, felt no subconscious twitch. That is better evidence than your theory of what the effect might conceivably be on somebody else.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO A. V. SESHAGIRI, OCTOBER 4, 1972

Nineteen-year-old A. V. Seshagiri wrote an eight-page letter from India. He had a severe stuttering problem. He said he was being tortured and tormented as a result of his speech impediment, and he also had problems with teachers. Mr. Seshagiri felt that they “discourage the students. They kill the enthusiasm of the students. . . .They do not want to give away their knowledge to the students.” He thought Caltech might instead be a place where he could study “calmly and peacefully without any anxiety.”

Mr. A.V. Seshagiri

Bombay, India

Dear Mr. Seshagiri:

Thank you for your letter.

It is fortunate that you are interested in physics because such a study is not seriously impeded by a speech difficulty. In fact physics must be studied alone—you must teach yourself. Do not worry so much about your instructors.There are very many books of varying degrees of difficulty and written in many styles, and on different aspects of physics.You must find the ones which suit you—which you enjoy reading and from which you can learn most rapidly and easily. In case you find my book interesting—although at present it might be too difficult for you—I’m sending a little book of problems to go with it. Do not be alarmed if you cannot do any of them now, take it easy, reading things you honestly understand first and your knowledge will grow.

Please be assured that the difficulties you are now having with your teachers is not an inevitable thing in India. I have spoken about what you wrote to a colleague of mine who lived in India several years and knows something of the situation. As you proceed to more advanced work you will encounter, ever more frequently, professors who are kindly and understanding of your problem.

It is extremely difficult to get into Caltech, as an undergraduate, from far away—but it is much easier as a graduate student (working for a Ph. D). In fact this year of the twenty new physics students, two are from India. I would suggest that you continue your studies there, in India, until you acquire a B. Sc. and also an M. Sc. Degree and then you can apply to graduate schools in the United States if you still wish to.

In the meantime, study calmly and quietly those things which interest you most and which you honestly can understand. I will not recommend any special books because it depends on your interest and level, you must find them yourself in the libraries of Bombay.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO BART HIBBS, OCTOBER 13, 1972

Bart Hibbs is the son of Dr. Albert Hibbs.

Bart Hibbs

Pasadena, California

Dear Bart:

You asked me to write you why I thought the sun looks red at sunset. Air molecules scatter blue light more than red.The color of the sky (in directions away from the sun) ordinarily is light scattered by the air and we all know the sky is blue.The light that is not scattered—that passes from the sun to the eye directly—has less blue in it—and even less blue the more air it goes through. Thus as it sets, and we look at it through a very long column of air it looks very red indeed.

The colors of clouds and sky at sunset are very beautiful but equally complicated—some are clouds directly illuminated by a setting sun—others are partly illuminated by light scattered a few times high in the sky, etc.

I hope that answers your question. If it only makes you think of more questions write me and I’ll try to answer those too.

Yours,

Dick Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO K. CHAND, M.D., NOVEMBER 6, 1972

Feynman was on his way to the Conference on High-Energy Physics in Chicago when he tripped on a sidewalk partially concealed by long grass and broke his knee cap.

Dr. K. Chand, M.D.

Chicago, Illinois

Dear Dr. Chand:

I am one of your patients who had a knee cap removed September 7. You asked me to write about my progress a month or two after I left the hospital. All is well and progressing exactly as you predicted—I can bend it 90 degrees today (that’s why I remembered to write) and it has been increasing at about 1 degree per day.Thank you and Dr. Kuhlkani for doing such a good job. Please send my special greetings to Dr. Kuhlkani.

The trip in the airplane was very easy.They had wheel chairs ready at departure and arrival. They put me in a special seat near the entrance so there was leg room, but—better than that—since the plane was not full they arranged for the seat on each side of me to be unoccupied—so I had three seats together and rode the whole way with my leg comfortably on pillows up on the three seats (American Airlines).

I rather enjoyed my stay in the hospital and remember with pleasure many good people—even besides the doctors!—for example Henry Pinicke the nurse, Miss Chan, the diet girl, Mr. Blas and Joyce in the physical therapy department, etc. (except I was astounded at how much the insurance company had to pay for each day I stayed there!)

When I break my other knee cap I hope it will be in Chicago so I can see you all again. I am making a trip there (to the National Accelerator Laboratory) in early December and if experience is any teacher I will break it there, so be prepared.

Yours sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO MALCOLM GIBSON, DECEMBER 29, 1972

Mr. Malcolm Gibson, age fifteen, wrote from England to ask what Feynman’s personal reasons were for working on the bomb, “knowing the consequences of your work.” He could appreciate that Feynman’s time was valuable, and “above all you must feel that you do not have to justify your actions to me.” He ended by saying he was not sure whether Feynman had worked on the atomic bomb project and apologized for disturbing him if that was not the case.

Malcolm Gibson

Yorkshire, England

Dear Malcolm:

I did work on the atomic bomb. My major reason was concern that the Nazi’s would make it first and conquer the world.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO NIELS FOSDAL, MAY 9, 1973

Mr. Niels Fosdal

Copenhagen, Denmark

Dear Mr. Fosdal:

I, of course, accept the great honor of your offer of the Niels Bohr International Gold Medal, what a pleasant surprise! My wife and I will be delighted to be in Copenhagen from Sept. 30 to Oct 7 as you suggest. (We are contemplating bringing our 11-year-old son.) I will be glad to give a lecture, but I have still to decide on what subject.

Thank you for considering me worthy of the medal.We shall take full advantage of the chance you give us to visit Copenhagen. I know how wonderful it is, having already visited a few times, but my wife never has, and I shall be pleased to show it to her.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO BEN HASTY, JUNE 1, 1973

“Happy Birthday Richard Feynman! From a grateful General Physics class, which used your lecture book. Thank you?” The hand lettering on the accompanying card is decorated with mathematical symbols (arrows, symbol for sum, increment signs, infinity signs, carats, exclamations, dot product signs, integral sign for the “F” in his last name, etc.) and has sixteen signatures.

Ben Hasty

Springfield, Missouri

Dear Ben:

I wouldn’t believe it if I didn’t see it myself. A grateful physics class that sends a birthday greeting to the author of their textbook! In my time it was conventional to hate the author of the textbook which brought such pain upon us all. Maybe times have changed—but I see you haven’t fallen absolutely, there was, at least, a question mark after “thank you.”

It was very nice of all of you and a very great surprise. One more unbelievable story to tell my grandchildren.

Thank you very much, and good luck.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO AAGE BOHR, SEPTEMBER 6, 1973

Professor Aage Bohr

Copenhagen

Dear Aage:

I should be glad to talk to physicists or physics students at any time—but prefer not to give a formal talk—could we just try getting together and discussing things through questions and answers? If you don’t think that is a very good idea let me know and I’ll try to think of some prepared subject—but I hope I do not have to.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO H. B. HINGERT, SEPTEMBER 12, 1973

Professor Hingert wondered if he had misunderstood that Feynman had learned Spanish before lecturing in Brazil, and thought he must have learned Portuguese instead.

Professor H. B. Hingert

Milan, Italy

Dear Professor Hingert:

Thank you for your note. The Feynman Lectures are published by Addison Wesley and are, I believe, available in English book stores.

I did learn Spanish before I went to South America. I had expected to travel somewhere in South American but I hadn’t decided where and was learning Spanish in preparation. But then I received an invitation to visit Brazil to do research there for three months.The invitation came six weeks before I was to go and I spent the six weeks “converting” my newly learned Spanish to Portuguese. People like to make up stories about how I have been foolish on occasion. So I let this story stand, as if I didn’t know they speak Portuguese in Brazil. I hope they will be satisfied with that story and not probe deeper to find out how much more of a fool I have been on other occasions and start stories about those.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

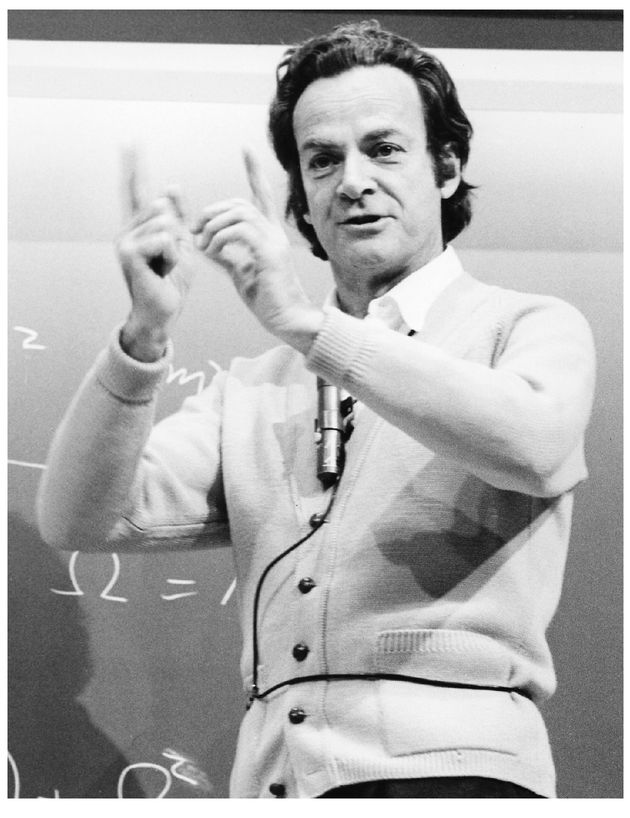

Receiving Niels Bohr Medal in October 1973 from Queen of Denmark, Margrethe II.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO HUBERT SPETH, OCTOBER 10, 1973

Hubert Speth

San Gabriel, California

Dear Mr. Speth:

Thank you for the kind note of good wishes.We went to Copenhagen and have just come back. Carl was with us, and you were right, he was beaming with pride to see his daddy get a medal from the queen.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO EDWARD FREDKIN, OCTOBER 18, 1973

Professor E. Fredkin

MIT

Dear Fredkin:

I have to thank you for a number of things.

There is a fellow here at Caltech, M. Weinstein, who is interested in “artificial intelligence,” whatever that is. He suggested to me that I come to work regularly on a computer terminal that connects to all the advanced systems in the county, so we could see what happens. I guess I am to get familiar with present computer abilities and think about what we need next, etc., or something. I will get a lot of fun out of doing that. He said you suggested he try me, so I thank you.

Maybe, if you would like to, you can give me advice on what you would like to see me doing, or thinking about. I haven’t yet made head or tail of what we are doing. I am starting out with MACSYMA. A man named Don Brabstone is teaching me. Do you have suggestions as to directions of thought? My very first impression is that MACSYMA is not smart enough to be very helpful in the little algebraic manipulations I need to do in my work from time-to-time, but I don’t know if that is a relevant observation (if, indeed, it ultimately turns out to be true).

On another subject:You once gave Caltech money for me to use as I liked. I never could figure out a good use. But last year a good research man (has Ph. D.), named Finn Ravndal, felt he had to go back to Norway (his home) to get a job. I had worked closely with him and we had written a paper together, and I was rather unhappy about (a) that we had to separate and (b) he would get stuck in Norway in a job much below his talents and interest. Suddenly I remembered your gift—proposed a year appointment for him here using it—and saved the day. Our field (high energy physics) has suddenly become pregnant with ideas and excitement and our working together this year will be great.

And, in the meantime, he has been offered a job for next year at the Bohr Institute at Copenhagen, which is a very respectable and excellent place. So we saved a good man.Thank you.

I donated your Muse to the boys in one of the rooming houses after thoroughly enjoying it myself.

What new things are you up to these days?

Sincerely,

Dick Feynman

The “Muse” Feynman spoke of was a digital music box of sorts. To Professor Fredkin’s knowledge, this box was the first device made for ordinary people with digital circuitry in it.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO R. B. LEIGHTON, APRIL 18, 1974

Subject: Memo re: Professor E. Fredkin

Prof. E. Fredkin, present director of project MAC, the computer science laboratory at MIT, has shown an interest in visiting Caltech for a year, next year.There are many branches of computer science and the interests of our people here in that field are varied, so that although the kind of work Fredkin does is of direct interest to some, that is not true of everyone in that division. Therefore, it would help if others would also support a recommendation that he come as a Fairchild fellow.

There is one direction of computer science that has particular personal appeal to me. (It is called by the unfortunate name of “artificial intelligence,” unfortunate because in the past several obviously naïve ideas went under that name.) Virtually all computer programs today simply follow step by step instructions—they do exactly what you tell them.They can make no use of some sort of explanation of what you are about or what you want done, and figure out how to do it themselves. As an example there is a big industry of programming. Given a problem, such as to make a computerized inventory system for a business, one must hand the problem over, with explanations of what you want, to a programmer. The programmer does a great deal of work to write a program of instructions for a computer to do what you wish.To what degree can we use machines to help in this programmers work—ultimately to make machines which program themselves with little more information than we now give the programmer who at present makes the program?

In psychology there is a profound question of what type of facility is it that permits a child to learn a language from simply hearing it spoken and seeing it used.We are far from knowing how it is done. It is even very hard to see how it can be done. But it is done by every child.We cannot expect to solve such problems by studying machines. Nevertheless, it is an intriguing academic investigation to see, at least in principle, some way that it might be done by a machine. In that manner we could at least start to guess at what kind of facilities the brain might have that enables it to learn language. In addition, if such a machine (or one with less but analogous abilities) could actually be designed or implemented by software on present machines, it would be of just the kind capable of automatic programming.

It is understood at MIT that such problems are exceedingly interesting. They are doing very promising work on them. I intend to spend some part of my time next year to thinking about these thoughts. Discussions with Fredkin would be very valuable.That is why I personally would like to support this recommendation.

But Prof. Fredkin’s visit would have much wider interest than just this. Prof. Fredkin has had experience in the practical and business sides of computers as well as having visions of how the science and the industry should develop. For example, he was one of the early investigators of the development of on-line and time-sharing computer terminals done largely at MIT. He is well-known for his invention and development of special software and also hardware for image-processing. He also was a prime mover in the interesting development of computer software to handle symbols, algebra, equations and calculus. (The system developed at MIT is called Macsyma.)

Having Prof. Fredkin here could help us still further broaden our range of computer interests.We could widen the opportunities of an ever greater number of our students interested in computers.

I think that this visit would be a good opportunity for Caltech, and I should like to add my name to those of the computer science department which have recommended him. I hope others of the physics department would agree, so that we can show a sufficiently campus-wide interest in his visit to be able to get him here.

Professor Feynman

c.c. Prof. F. H. Clauser

Prof. M.Weinstein

Professor Fredkin came for the year, and incidentally, so did Stephen Hawking, another Fairchild Fellow.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO PAUL OLUM, OCTOBER 31, 1974

Paul Olum, a colleague and friend of Feynman’s since the days of their graduate studies at Princeton University together, wrote to ask Feynman to speak at the University of Texas. Dr. Olum had become the Dean of the College of Natural Sciences there, after a brief stint in administration at Cornell University. Dr. Olum remarked that his decision to leave Cornell University for the University of Texas had a lot to do with the fact that he felt it was“a lot more exciting and creative to be part of building something than to try just to keep the quality that is already there which would have been the case largely at Cornell.” The letter ended with Dr. Olum uncertain if he would stay at the University of Texas, as the President had recently been fired.

Professor Paul Olum

College of Natural Sciences

The University of Texas

Austin,Texas

Dear Paul:

Great to hear from you. I am sorry to hear that you have been unable to resist getting a case of our occupational disease. Fortunately I myself have not succumbed and am still doing physics with as much pleasure, although not as cleverly, as ever.

I am happily married to an English wife and have two kids (boy 12, girl 6) all of whom are a delight and make me very content. I feel like at last all of life’s problems are solved!

But being so content at home and at work here makes me very reluctant to go anywhere else, even for two weeks. So although sorry not to see you again, I shall decline your invitation to visit Austin.

Best regards,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO DAVID PATERSON, NOVEMBER 19, 1974

Mr. David Paterson

BBC TV

London, England

Dear David:

I saw your quark-hunting program the other night and want to congratulate you on a first-rate job. I know how difficult the subject must have been for you, as an outsider, but you must have conquered it completely to be able to put all those pieces of interviews and apparatus together into such a coherent entirety. It told the story of what we physicists like to think of as an abstruse subject in a very clear and simple way. I was surprised it could be done, but you proved it to me.

I also must admit being a bit proud of my colleagues when I saw how well they explained themselves. Physicists didn’t seem to be such a bad lot, after all.

The importance of such communication goes, of course, without saying; we both understand that.

So thank you.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO ROBERTA BERRY, DECEMBER 18, 1974

Mrs. Berry wrote to obtain permission to reprint “What is Science?” for a college course called “The Citizen and Science.”

Mrs. Roberta Berry

Editorial Assistant

Indiana University

Bloomington, Indiana

Dear Mrs. Berry:

OK Mrs. Berry—but times have changed since I gave that speech in 1966. So some of the remarks about the female mind might not be taken in the light spirit they were meant. Perhaps there is nothing we can do after all these years—but if after you read those remarks you still want to print it as is, it is OK by me.

Sincerely yours,

R. P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO B. E. BUSHMAN, JANUARY 7, 1975

B. E. Bushman wrote, wanting a reference for the idea of “partons.”

B. E. Bushman

Laguna Beach, CA

Dear Mr. Bushman:

I can’t suggest a simple reference.The idea is discussed at length but very technically in my book “Photon Hadron Interactions” published by W. A. Benjamin.

However, the word means something simple—if we can suppose that protons, neutrons, pions etc., are not “elementary” but themselves made up of more fundamental parts, that is they are made of simpler particles (just like atoms are made of other particles, electrons and nuclei—or electrons, protons and neutrons) we needed a name for these unknown particles—that name is “partons.” The next question is “what are the partons like?” that is, what charges do they carry, etc. (if they exist).

At present it does look like this idea is good and most of the partons are quarks (but there may be other uncharged kinds too.)

Sincerely,

R. P. Feynman

DAVID A. MARCUS TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, JANUARY 13, 1975

Dear Mr. Feynman,

At the stage of atomic research and control would you consider nuclear energy the curse of humanity or the potential salvation of mankind?

As one who contributed so significantly to the means of man’s utilization of this awesome force, what are your thoughts as you look back at this scientific development?

Do you look to the future with fear or with hope?

I am an amateur historian and sociologist and I would be most grateful for your comment.

Respectfully,

David Marcus, D.D.S.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO DAVID MARCUS, FEBRUARY 18, 1975

Dr. David Marcus

Palm Springs, California

Dear Dr. Marcus:

I am sorry to have to answer your question (as to whether I consider nuclear energy a curse or a salvation of mankind) that I really don’t know. I look to the future neither with hope nor fear but with uncertainty as to what will be.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO DAVID HAMILTON, MARCH 26, 1975

On February 22, 1975, a retailer of office equipment wrote to Feynman seeking comment on an idea that he had conceived. Mr. Hamilton began by noting that he had already written to Feynman’s colleague Murray Gell-Mann but as yet had received no reply. He hoped Feynman would respond, since he had so enjoyed Feynman’s appearances on public television.

Mr. Hamilton’s idea was to construct an accelerator for fundamental particles in the shape of a figure 8. Such a shape would have the advantage, he said, that the particles could collide with each other as they raced in opposite directions through the crossing point of their 8-shaped path. He asked whether new particles produced in such a collision might move faster than light, since the relative speed of the colliding particles would be almost twice that of light, and he suggested using a variant of a particle detector called a spark chamber to study the particles.

Mr. David Hamilton

Venice, Florida

Dear Mr. Hamilton:

Your idea is a very good one. So good that it is in full use now, in a machine we call a colliding beam machine at the European Organization for Nuclear Research which is in Geneva, Switzerland. They use protons whose energy is so high their mass is thirty times enhanced (by relativity effects).Their velocity is less than the speed of light by only one part in two thousand.They go around in two rings that intersect at one place where experiments are done to see what happens.The protons from an accelerator are “stored” in the rings where they go around and around, colliding from time to time in the intersection at A. To get the same kind of collision in the conventional way (by hitting one fast proton against another at rest in the laboratory), one would need an energy sixty times higher than one has in these rings (that is protons whose mass is enhanced 1800 times).

Although in the usual way of figuring, since each proton is going nearly at the speed of light, it seems their relative velocity is nearly twice the speed of light. But Einstein showed the regular way of thinking is wrong and relativity effects make the apparent relative speed of one as seen by the other less than the speed of light (by only one part in 7,000,000 in this case!).

Spark chambers (and other devices) are indeed used to study the particles produced in the collisions.Very interesting results are obtained which we are all puzzling over, trying to fully understand.

There is a similar colliding beam device at Stanford University (SLAC), but here there is only one ring with electrons going around one way, and positrons the other way. A few months ago an entirely unexpected new particle (called a ø, about three times as heavy as a proton) was found. It is destined to change, drastically, our ideas about what matter is made of.

So your idea is at the experimental forefront of high energy physics today. I hope you are not too disappointed that it had already been thought of.

Yours sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

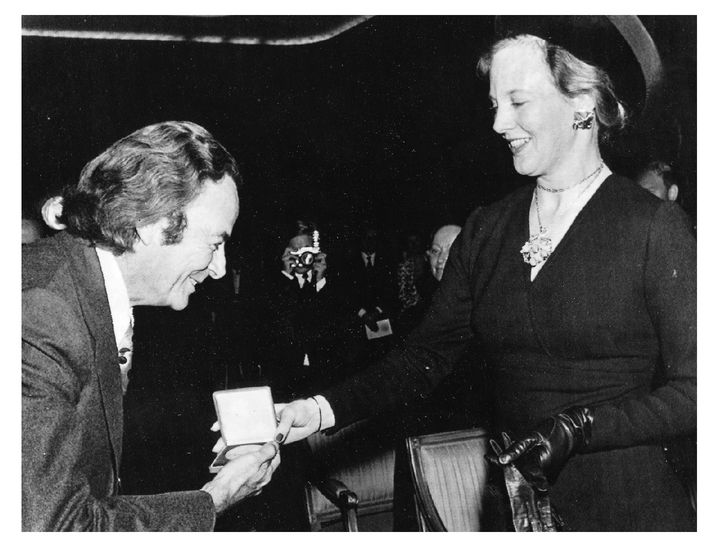

One of “Ofey’s” sketches.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO WILLIAM L. MCCONNELL, MARCH 5, 1975

William L. McConnell, who had been working pairing talented high school students with researchers in the St. Louis area, was intrigued by the notion that those with higher levels of intelligence could work in more disciplines than most people. He had learned that Feynman had taken up drawing and wanted a sketch for his office wall.

Dr.William McConnell

Director, Science MAT

St Louis, Missouri

Dear Dr. McConnell:

I don’t know much about the “general theory of intelligence,” but I do remember when I was young I was very one-sided. It was science and math and no humanities. (Except for falling in love with a wonderful intelligent lover of piano, poetry writing, etc.) It is only as I became older that I tried drawing (starting 1964). Bongo playing has never been “music” to me—I don’t read notes or know anything about conventional music—it has just been fun making noise to rhythm—not much “intelligence” in the intellectual sense is involved.

I am sorry not to want to send you a drawing, because it has been my policy not to sell them to people who want them because it is a physicist who made them.

Sincerely yours,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO KENNETH R. WARNER, JR., APRIL 1, 1975

On March 6, 1975, a man who had seen Feynman on a PBS Nova program and struggled to understand The Feynman Lectures on Physics wrote to him seeking help. Mr. Warner prefaced his question by expressing dismay at Feynman’s apparent dismissal of dilettantes in the Nova program, since Mr. Warner’s own life circumstances forced him to be a dilettante. He then described the great pleasure he got in figuring things out, such as why, as described in Feynman’s book, a particle, bouncing off a wall, transfers a momentum 2mv to the wall (where m is its mass and v its speed). The factor 2 results from the particle first having to stop its motion and then start it again.

Mr. Warner then posed his question: In Chapter 15 of the Lectures, Feynman had postulated that it is impossible to determine the absolute speed of a moving ship by means of experiments performed inside it (for example, experiments that compare the ticking rates of two different kinds of clocks). Feynman then used this postulate to deduce behaviors of some laws of physics, such as the increase of a body’s mass as it moves with higher and higher speed. Mr. Warner was puzzled about Feynman’s premise that it is impossible to determine absolute speed. How could that premise be justified? “I fail to see it and even that failure to see fascinates me.”

Feynman responded as follows.

Mr. Kenneth R. Warner, Jr.

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Dear Mr.Warner:

You certainly seem to understand much more than many dilettantes I have known. Anyone who stops to make sure of the 2 in ∆ p = 2mv is either not a true dilettante, or one in grave danger of becoming not one.

Your vision of hints of a reductio ad absurdum with the clocks is because you didn’t appreciate the source of something we put in. We have assumed it to be impossible to determine the absolute speed of our moving ship, not for any logical or necessary reason, but for the sake of argument, as a possible principle of nature.This principle was suggested by many experiments (e.g., one by Michelson and Morley) designed to measure the absolute velocity of the earth. They all failed, until it dawned on our dull human minds (in fact only on a few, like Poincaré’s or Einstein’s) that maybe it was impossible—and they set up to see what the consequences would be if we assumed this as a matter of principle. In the book I was following their type of argument. It was successful, the necessary consequential phenomena (like mass changing with velocity) were ultimately observed experimentally.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO MICHAEL STANLEY, MARCH 31, 1975

Mr. Stanley was a graduate student in pharmacology seeking advice on remaining fresh in methods of reasoning. “How is it possible to reach that high level of preparedness without stifling the creative process that permits the examination of problems in novel ways?”

Michael Stanley

Department of Pharmacology

Mount Sinai School of Medicine

New York, New York

Dear Mr. Stanley,

I don’t know how to answer your question—I see no contradiction. All you have to do is, from time to time—in spite of everything, just try to examine a problem in a novel way.You won’t “stifle the creative process” if you remember to think from time to time. Don’t you have time to think?

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

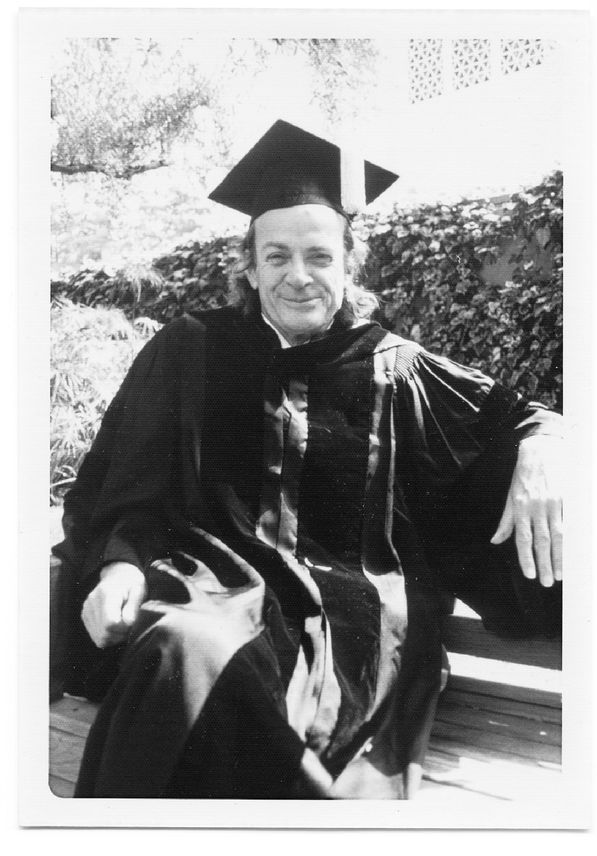

Caltech Commencement, 1975.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO EDMUND G. BROWN, JR., JUNE 23, 1975

The Honorable Edmund G. Brown, Jr.

Governor of the State of California

The State Capitol

Sacramento, California

Dear Sir:

I should like to urge you to support the school programs for the mentally gifted by signing Senate Bill 480.

I am a theoretical physicist (Nobel Prize 1965) whose son (13) and daughter (7) are very intelligent and intellectually active. I am often asked where I send them to school so that they can best develop their active minds. I am proud to answer,“the public schools of the State of California.” For in the regular public school they have both been happy students, where I would have expected the tedium and boredom I experienced in my day (in New York public schools). But schools have come a long way in improving the curriculum, and especially in recognizing the problem of providing materials in a variety to try to meet the variety in children’s minds. The biggest contributor to, in particular, my son’s happiness and development has been the special classes designed for his special type of variation—the programs for the mentally gifted minors.To an extent it is an oasis in a desert for both of them.

Keeping the better students intellectually alive and active is obviously useful to them, and to society, for their special talents are developed instead of being “turned off” by “education.” In addition, the competition from private schools is such that it would be a shame if parents of clever kids thought that to get them the “best” education they should take them out of the public schools (when on the contrary, the public schools are better!). For that would leave our schools relatively dull places, with fewer bright flashes from students to light up a teacher’s day and to suggest ideas to other students. Ideas suggested by fellow students shows the others what can be done and keeps standards and performances high.

My interest in state education is not just that for my own children, but as a teacher (of university physics) I have a general interest. I served on the State Curriculum Committee choosing textbooks for two years, 1964-65. So I urge you to continue the program to make our schools interesting to our best students.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

Richard Chase Tolman Professor of Physics

ILENE UNGERLEIDER TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, DATE UNKNOWN

Dear Richard

I’ve fallen in love with you

From seeing you on “Nova”

I’m so glad you’re alive

I appreciate your: wit

wisdom

brilliance

looks

You are a feyn-man

Are there lots of physicists with fans?

You have one!

Ilene Ungerleider

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO ILENE UNGERLEIDER, AUGUST 11, 1975

Ms. Ilene Ungerleider

Seattle,Washington

Dear Ilene:

I am now unique—a physicist with a fan who has fallen in love with him from seeing him on TV.

Thank you, oh fan! Now I have everything anyone could desire. I need no longer be jealous of movie stars.

Your fan-nee, (or whatever you call it—the whole business is new to me).

Richard P. Feynman

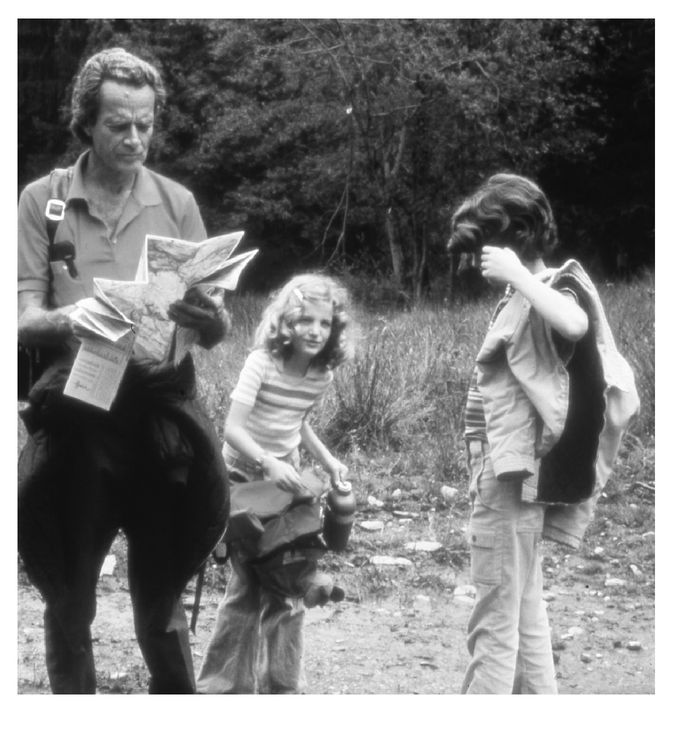

On a camping t rip, c. 1975.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO WILLIAM NEVA, AUGUST 14, 1975

“Being a layman, curious about creation and all its after effects, one question plagues me (as I’m sure it has you and thousands of others) and that is—CAN INVISIBILITY BE INDUCED, CREATED so as to render an object unseen by the human optical setup?”

—Mr. William Neva, in a letter to Richard P. Feynman, July 23, 1975

Mr.William Neva

Henrietta, New York

Dear Mr. Neva:

Thank you for your letter and for your question about invisibility. I would suggest that the best way to get a good answer to your question is to ask a first-rate professional magician. I do not mean this answer to be facetious or humorous, I am serious.What a magician is very good at is making things appear in an unusual way without violating any physical laws, but by arranging matter in a suitable way. I know of no physical phenomenon such as X-rays, etc., which will create invisibility as you want.Therefore if it is possible at all it will be in accordance with familiar physical phenomenon. That is what a first-rate magician is good for, to create apparently impossible effects from “ordinary” causes.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO DAVID RUTHERFORD, AUGUST 14, 1975

David Rutherford wondered if it would be possible to record dreams on tape, much like television shows are recorded.

Mr. David Rutherford

Davis, CA

Dear Mr. Rutherford:

The difficulty in seeing what goes on in the brain by just measuring brain waves is that the impulses are not truly transferable into video pictures that are being seen in the brain. If they were transferable it would have to be via some sort of code but we do not know what code. However, I am certain that the amount of information or detail that is in a dream image is enormously greater than that which is carried into the gross variations measured in the EEG. It is like trying to describe or “see” what a painting looks like just from some overall facts like the weight of the painting, or the amount of paint of each color used, etc. More detail, like where the paint is located, is needed. I am sure it is impossible to try to decipher the details of the impulses in the millions (?) of nerve fibers that constitute a dream image by just looking at the EEG effect.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

BEULAH ELIZABETH COX TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, AUGUST 22, 1975

Physicists think of electrical forces as produced by electric field lines that stick out of any electrical charge. Gauss’s Law states that the total number of electric field lines that cross through any closed surface (such as a sphere or a cube) is proportional to the total electrical charge contained inside that surface.The following exchange concerns Gauss’s Law.

Dear Dr. Feynman:

I recently took a course in Elementary Physics at the College of William and Mary in Virginia. An exam question concerned Gauss’s Law and conductors, namely, does a hollow conductor shield the region outside the conductor from the effects of a charge placed within the hollow but not touching it?

I read Chapter 5, Volume II of The Feynman Lectures on Physics, and understood all except the next to last paragraph, in which you say “. . . no static distribution of charges inside a closed conductor can produce any fields outside.” This was confusing, as it seemed to contradict all your previous statements. My instructor showed me how a simple application of Gauss’s Law, with the surface of integration enclosing the entire conductor, shows that the E vector outside the conductor is not zero.

Could you perhaps explain what the paragraph in question means? I would greatly appreciate a reply as I am now very confused. My address is above.

Sincerely,

Miss Beulah Elizabeth Cox

P.S. I must admit I have a devious motive in writing to you because on the exam I answered with the explanation that your book gave. However, my instructor did not give me any points, even after I found your book to validate my answer. If you could clarify this question for me, I would be very appreciative.Thanking you in advance.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO BEULAH E. COX, SEPTEMBER 12, 1975

Miss Beulah E. Cox

Williamsburg,Virginia

Dear Miss Cox:

Your instructor was right not to give you any points for your answer was wrong, as he demonstrated using Gauss’ law.You should, in science, believe logic and arguments, carefully drawn, and not authorities.

You also read the book correctly and understood it. I made a mistake, so the book is wrong. I probably was thinking of a grounded conducting sphere, or else of the fact that moving the charges around in different places inside does not affect things outside. I am not sure how I did it, but I goofed. And you goofed too, for believing me.

We both had bad luck.

For the future I wish you good luck in your physics studies.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO ALEXANDER GEORGE, SEPTEMBER 26, 1975

The question of whether “an independent breakthrough” was still possible in the present scientific world was one that Mr. Alexander George posed on September 20, 1975.At the time Mr. George was doing independent research and had been repeatedly told that research teams were needed for discoveries.

Mr. Alexander George

New York, New York

Dear Mr. George:

To answer your question, it depends on what branch of physics you are working on. In high energy physics the experiments are so complicated and elaborate and require such expensive machines that almost all experiments are done by large teams. But when it comes to a realization of what an experiment might mean, or to inventing and producing a new clever way of doing something—that might be done by one fellow independently. Finally, good theoretical work seems to me to be much as it always has been—good ideas appear in individual brains, not in committee meetings. Of course, as always, reading others’ work or conversations and discussions with colleagues helps a lot in preliminary stages of thinking.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO R. H. HILDEBRAND, OCTOBER 28, 1975

Professor R. H. Hildebrand

Chairman, Appointments Committee, EFI

The University of Chicago

Chicago, Illinois

Dear Professor Hildebrand:

This is in response to your letter of October 1. I am sorry, but I have a general policy never to write evaluations of people for institutions where that person has recently spent time, or is still located. My reason is that the people at the institution have had ample opportunity to observe him themselves (more recently, and more closely, than I) and should be capable of making their own evaluation.

This is a general rule I follow and has, of course, nothing to do with the particular individual about which you asked me.

Also for that reason, I can make no exceptions, for otherwise others to whom I have applied my rule will misinterpret my refusal to write, if they were to find out that I sometimes do write such evaluations.

I am sorry, therefore, to have to refuse your request.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

After the letter to D. S. Saxon on October 20, 1964, Feynman wrote this type of letter whenever he was pressed by an institution for an evaluation of someone who was still at that institution.

STATEMENT BY MAX DELBRÜCK AT THE PRESS CONFERENCE ON BEHALF OF ACADEMICIAN ANDREI SAKHAROV, ORGANIZED BY THE CALIFORNIA COMMITTEE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS, DECEMBER 9, 1975

In 1968, decorated Soviet physicist Andrei Sakharov wrote an article that was smuggled out of the Soviet Union and published in The New York Times. Titled “Reflections on Progress, Peaceful Coexistence, and Intellectual Freedom,” it was highly critical of the Soviet political system and highlighted the risks of radioactive fallout from nuclear tests to hundreds of thousands of innocent people. Sakharov’s efforts to ban nuclear testing, as well as foster democracy, won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975. The Soviet government refused to let him attend the ceremonies.

The following statement was drawn up by Max Delbrück, winner of the 1969 Nobel Prize in Medicine and a friend of our family (we went on many camping trips with the Delbrücks). Feynman associated himself with the statement, as did fellow Laureates Harold Urey, Carl Anderson, and Julian Schwinger.

Sakharov’s plans for greater openness became widely known in the West in 1968 through his magnificent 10,000 word essay, “Progress, Coexistence and Intellectual Freedom,” which was reprinted at the time in the N.Y.Times.

He argued that the capitalist and the socialist systems have great merits and demerits. There should be a freer flow of information, of visits, and of open critical discussion, to accelerate the natural process of convergence between the two systems, and thus lead to a more humane way of life for all of us, including the Third World.

The Nobel Committee of the Norwegian Parliament in Oslo wished to applaud Sakharov’s ideas and to give them wide public attention.They also wished to give recognition to his unremitting efforts in organizing campaigns for human rights, especially the right to public dissent, and to his forceful and courageous stand in many individual cases of human rights.

The authorities of the USSR have, perhaps unwittingly, supported the Nobel Committee’s intentions: by denying Sakharov permission to travel to Oslo they have enormously increased the world-wide attention given to his ideas. Thus they may not have done him a favor, personally, because he would have probably enjoyed the trip. But they have done his cause a favor, by enhancing public attention to it. Surely we would not be here today if Sakharov’s presence in Oslo tomorrow were not very much in doubt.

Sakharov is a scientist of the highest caliber, and a great citizen of the world. He is, perhaps most of all, a great Russian patriot, belonging to what we would call his government’s loyal opposition, a concept unfortunately not entirely accepted in the USSR.

We wish to join his many friends in the USSR and abroad in saluting him on the day of the award to him of the Nobel Prize for Peace.