1985-1987

In January of 1985, a collection of Feynman stories appeared under the title Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!: Adventures of a Curious Character (triple entendre intended). Far exceeding both my father’s own expectations and that of his publisher, it went on to spend fourteen weeks on the New York Times best-seller list.That same year also saw the publication of QED:The Strange Theory of Light and Matter, Feynman’s painstakingly accurate and detailed explanation, using very little math, of quantum theory for a lay audience (if you want to understand what he got his Nobel Prize for, this book is for you).

In 1986, at the invitation of former Physics X student Bill Graham (then acting administrator of NASA), Feynman reluctantly agreed to serve on the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident, an experience he recounted in depth in What Do You Care What Other People Think? At a critical moment in the hearings, Feynman dipped O-ring material from a rocket booster into a glass of ice water, dramatically demonstrating the technical cause of the accident.

Richard Feynman died less than two years later, on February 15, 1988. When he briefly emerged from a coma induced by kidney failure, his last words, spoken to the three women by his side (wife Gweneth, sister Joan, and cousin Frances), were: “I’d hate to die twice. It’s so boring.”

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO SILVAN SCHWEBER, JANUARY 28, 1985

Dr. Schweber sent a draft of his chapter, “Feynman and the Visualization of Space-Time Processes,” which he had written as part of his book Quantum Field Theory, 1938-1950. Dr. Schweber assumed that Feynman would find the chapter boring, but he hoped there were things that would be new to him. Dr. Schweber was striving for an accurate account and welcomed any comments or criticisms from Feynman.

Dr. S. Schweber

The Martin Fisher School of Physics

Brandeis University

Dear Schweber:

Well, I am sorry for the delay.We had a calamity here and lost everything pertaining to you—your manuscript and my notes on it to you. So I’ll try again.

First, I didn’t find it boring but very exciting and surprising to find things I thought gone forever, like the page of typing on complex numbers that I remember seeing before me in my almost toy typewriter—but I didn’t think still existed! Also I didn’t know I wrote so many letters so it was fun to see what I was thinking.You historians have a way of recreating the past until it appears almost real.

Here are some comments on possible corrections but I know it is only my memory against ‘facts.’There were several typos but I didn’t bother with those.

p. 4 last para. I think I entered MIT in Math (course XVIII). After a bit I went to Franklin (then head of Math Department) to ask “what is the use of higher mathematics beside teaching more higher mathematics.” He answered, “if you have to ask that then you don’t belong in mathematics.” So I changed to practical, Electrical Engineering (course VI), but soon oscillated part way back to Physics (course VIII) and stayed there.

p. 9 central para. (Comment) I didn’t know that they thought of three years instead of four. How fortunate that they didn’t do it!

p. 9 top para. The scholarship to Harvard was the prize for winning a country-wide math contest (Putnam?). The math department asked me even though I was in physics, to enter because they didn’t have the four men needed to enter a team—but looking at records had found I had been in math. I was unsure, but they gave me old exams to practice on.

p. 14 2nd para. Among the “others” was John von Neumann.

p. 17 3rd para. Should read “In this newer version, they gave...”

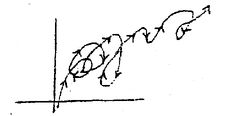

p. 24 last para. (Comment) My interest in this came from this: In high school I had a very able friend Herbert Harris who, when we graduated, went to Rensselaer Polytechnic to become an electrical engineer, while I went to MIT. One summer (end of freshman year?) he returned to Far Rockaway, we friends took a walk, and he told me about the then new feedback amplifiers. He tried to design them in different ways avoiding oscillation and said he was very convinced that there was some law of nature that made it impossible to make the impedance fall off too fast without inducing a large phase shift. I proposed it might be a reflection in the frequency response domain of the fact that signals cannot come out before they come in, but neither of us was, apparently, sophisticated enough to work this out mathematically—but you see why four years later I would find Bode’s paper so interesting. p. 23. I find no reference to fig 1 in the text.The figure (if I guess what it refers to) should be more like

or other more complex knot.

p. 25 line 12 (also p. 36 top). I joined Wilson’s group for war work before I finished my thesis—and stopped working on it. After a time I did ask for some weeks off to write my ideas on it myself so I wouldn’t forget them. But while doing that I saw (probably erroneously) a way to solve a problem that was holding me up, and Wheeler suggested I quickly write it all up and finish getting my degree.

Comment. Generally, I am not bothering to check all the equations, etc., on these pages.

p. 32 top line 6. I didn’t know how to calculate a self-energy in the conventional way with the Dirac theory and holes because I had never studied it carefully, and my path integrals hadn’t been clearly developed for the Dirac electron going backward in time yet. But I did know how, in an obvious way, to reinstate the terms representing electrons interacting with themselves. I tried to translate the modification I was proposing into a rule (the scheme of F60, p. 65) for integrating over frequencies or photons of various masses and returned next day to ask Bethe to try it on the conventional calculation that he, but not I, knew exactly how to do.

p. 40 top. It would be nice to get Aage Bohr’s recollection of all this, for I only saw it from one side and may have been partly guessing what went on between his father and him.

p. 66 top para. No, it was other people I was referring to who had to keep transverse and longitudinal terms separately—I had known since the time of my thesis, 1942, that they went easily together. In the quote what I meant was “. . . had been worked out so patiently (by everybody else) by separating. . .”

p. 66 line 16. Possibly error for “(except for some nice simplification ways)”. Next line, possibly “somewhat less sharp.”

p. 70 top para. The story of this mistake is interesting. As near as I can remember it, I first got a relativistic result (we were only working to order v2/c2). A student found an error in an early line and concluded it would not be invariant—when I wrote the first letter p. 66*. But later on several pages later he found another error where I canceled two equal complicated terms that I should have added. The original answer I had gotten was right—it was relativistic.This miracle of two canceling errors was probably the result of a mixture of having a strong feeling for what the answer must be and algebraic carelessness.

p. 71 2nd para. It is possible I remember things the way I would like but I suspect this Eyges story never happened. Could you get Bethe to confirm it? Schwinger and I compared notes and results and we were good friends. We discussed matters at Pocono and later also over the telephone and compared results. (We did not understand each other’s methods but trusted each other to be making sense—even when others still didn’t trust us.We could compare final quantities and vaguely see in our own way where the other fellow’s terms or errors came from.We helped each other in several ways.+) Many people joked that we were competitors—but I don’t remember feeling much that way. And in my letter, p. 70, one reads my thoughts (in the last para.) that I am excited because an old problem may have been solved either by me or Schwinger. Doesn’t sound too competitive.

+ For example, he showed me a trick for integrals that led to my parameter trick, and I suggested to him that only one complex parameter function ever affected rather than his two separate real functional (i.e.: they would always end up in the combination D1 + iO2 in the final answer).

p. 76 line 14.The “bombardier metaphor” was suggested to me by some student at Cornell (who had actually been a bombardier during the war) when I was writing up my paper and was asking for opinions of how to explain it and only had poor and awkward metaphors.

p. 76. Why is “phantezising” spelled wrong? Can we trust the typist recording the taped oral interview to know how badly I spell?

p. 87 Actually I also had the impression that Aage expressed, that Schwinger had more complete results because he had a charge renormalization whereas I hadn’t yet done vacuum polarization satisfactorily. As you know there are four diagrams.

We (Schwinger and I) later found that I had I + II + III (no charge renormalization) and he had I, without II, III and so with a charge renormalization that I (confusedly) thought was due to the vacuum polarization IV. I didn’t have IV at the Pocono, and I thought he did. (I do not now know whether at Pocono he really did have IV satisfactory or not.)

p. 100 4th para. From end. I think I expressed myself badly in “that was the moment I got my Nobel prize.” I didn’t mean that was when I knew I would win the Nobel prize—which never entered my head.What I meant was that was the moment I got a “prize” of thrill and delight in discovering I had something wonderful and useful.

p. 106 Is it necessary to include these religious views? People are often sensitive about such things and they are best presented in a quiet gentle way as I tried to do in my full talk.The short quotations may be more shocking (Oh well, not, I guess, to your readers!)

p. 107 Professor Morgan Ward pointed out to me that the same argument would show that an equation like x7 + y13 = z11 (powers prime to each other) would be unlikely to have integer solutions—but that they do, an infinite number of them!

p. 111 1st para.There is no reference for footnote 196.

p. 111 last para. It is not proper for an historian who is writing for posterity to tell us what posterity will think. He should be content to present the evidence to permit “posterity” to come to an opinion, but not to formulate that opinion for it. In all other remarks you give full references in footnotes.Where is your reference for this paragraph?

Almost my entire knowledge of Quantum electrodynamics came from a simple paper by Fermi in the Reviews of Modern Physics (1932).

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO BERNARD HANFT, FEBRUARY 4, 1985

Mr. Bernard Hanft sent a washer with thread attached to demonstrate what he called a new physical force, “The Hanft Force.” The Hanft Force operates as follows, he wrote: “It will cause a suitably suspended object, of any substance, and of any configuration, to spin, on its axis.” Mr. Hanft felt that since there was no energy used, the Hanft Force could be developed into a source of unlimited free power.

Mr. Bernard Hanft

Rego Park, New York

Dear Mr. Hanft:

Thank you for sending me your note about the spinning force and the perimeter force, as well as the washer and thread with which to demonstrate it.

The spinning force is a delightful phenomenon and appears quite puzzling at first. However, I have done some experiments and believe I know how it works in spite of the apparent violation of the laws of energy conservation. I shall suppose that the fibres of the thread have a natural tendency to be twisted in the state of lowest energy (presumably because of twists put in manufacture). More simply, I mean when there is no pull along the thread, the thread is twisted.Then when you pull it—for example by the weight of the washer—it tends to untwist at least partially—for it can become longer—giving in to the force by untwisting.

So, when you hang the washer on the thread, the thread untwists rotating the washer.The energy comes from the fact that the thread becomes longer as it untwists—and lowering a weight (of the washer, in this case) can supply the energy of rotation.

To verify my prediction, that the string lengthened, I hung the washer on the thread from a fixed point and carefully marked the position of the top of the washer.When it was in full spin it was indeed lower but by only a little over 2 millimeters! At first I was surprised because I didn’t think the energy released in such a short distance could account for such a vigorous spinning, as the washer acquires. But a short calculation showed that my intuition was wrong.The energy released in falling two millimeters is about the same as the kinetic energy of a disc spinning at a rate of three full rotations per second. (I judge the disc spin to be not quite as fast as that—but we lose energy in friction in the thread and in air resistance.)

When the thread is released, the tension of the weight is taken off, and the thread is free to spring back to its original more twisted and shorter configuration.Thus the experiment can be repeated again and again.

The perimeter force effect is less interesting because it is more well known.There used to be a parlor trick using a girl’s ring on a thread held by the girl to answer questions yes or no depending on whether the ring goes in a clockwise or counterclockwise ellipse.The motion is caused by inadvertent and unconscious slight motions of the hand.That is why, as you report, it works only if the thread is held in your hand. Try holding it in your hand, but a hand which cannot move because it is held up against a shelf or other rigid object (be careful your fingers don’t move also).

Thank you again for calling my attention to these entertaining phenomena.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

ROBERT F. COUTTS TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, APRIL 1985

Dr. Feynman,

I have been nominated for the Presidential Award for Excellence in Science and Mathematics Teaching. Reception of this award unfortunately requires various recommendations and I decided quite presumptuously to request that you write one for me. I would very much appreciate a brief note, perhaps mentioning the many years that you have been coming to Van Nuys High and the joy we share in a good Physics lesson. I know that writing recommendations is a pain in the neck and I shouldn’t ask, but I decided to let the prospects of fame and glory cloud my reason.Thanks for your consideration.

A note to your trusty secretary, the Presidential Award program says I must have it all post marked by April 19th.

My students and I look forward to your visit on the 24th.

Gratefully,

Bob Coutts

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO MELINDA JAN, APRIL 16, 1985

Ms. Melinda Jan, Science Chairperson

Presidential Awards Program

California State Department of Education

Sacramento, California

Dear Ms. Jan:

I was pleased to hear that Robert Coutts has been nominated for the Presidential Award. One of my little pleasures in life is to go to the Van Nuys High School once or twice a year to answer questions for the science students of Mr. Coutts’ classes.This activity was initiated many years ago by Mr. Coutts and I look forward to doing it every year.The questions are on anything, relativity, black holes, clouds, spinning tops, magnetic force, you name it.The class is alive and very interested and seems to enjoy it as much as I. That they are so alive and ask so many questions, is, I have always supposed, a result of Mr. Coutts’ love for science and education (for he never fails to want to show me some new experiment, device or original way of explaining something in the few minutes before the class begins).

If you select him you can be proud of your selection.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

Richard Chace Tolman Professor of Theoretical Physics

DEBBIE FEYNMAN TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, JANUARY 20, 1985

Dear Dr. Feynman,

I am prompted to write to you at this time for various reasons you will understand as this letter continues.

First, let me explain our relationship. My father is Bert Feynman, son of Frank Feynman, who passed away in 1966. My grandfather, Frank Feynman, is the son of Harry and Sarah Feynman. I believe, correct me if I am wrong, you are the son of my great grandfather’s brother.That makes me removed about four times, and my father, Bert, about three times as cousins.

My name is Debbie. I am going to be 17 years old in this April. I go to Forest Hills High School, half way through eleventh grade. My curriculum at school is called the Math-Science Honors Program. My science teachers in the past have asked me if I was related to you. Of course, my answer is yes, as you are a cousin to my father. I felt very proud of this, as you are held in high esteem as a scientist and as a person amongst the scientific world. I have seen you on T.V. on our channel 13 early last year, when you made an hour long interview program.

This summer my mother, whose name is Audrey, and my father are sending me on a teen tour, which will include going to California. How close I will be to where you are I can’t determine yet, but it would be a great treat to meet you if possible. It certainly would make my father proud, also.

Since this is our first correspondence, it is a little difficult to be definite, not knowing about your immediate family and etc.

You should know that my father and mother have great interest in my writing you as I have.You should feel free to write or question anything you might have in mind at the time.

I will be anxiously waiting for your reply, and send my very best to your family.

Sincerely yours,

Debbie Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO DEBBIE FEYNMAN, MAY 7, 1985

Ms. Debbie Feynman

Forest Hills, New York

Hi Debbie:

It is fun to find someone signing letters with my name, that isn’t my wife, child, or sister. Of course, it is because it is your name too. It is such a crazy name that we must be long-lost relatives—nobody could have invented it twice.

But how are we related? It will require more detective work. All I know is that my father Melville, had a brother, Arthur, who died without children, and two sisters who changed their name upon marriage. My grand-mother’s name was Anna. She lived in Brooklyn. Her husband’s name was Jacob Feynman.They had trouble and he ran off to California and remarried (some “Feynmans” exist in California in Long Beach).

The story, as far as I or my sister knows, was that Jacob’s name was Pollock but, when they immigrated here, he took the name of his wife (or an approximation of it, maybe it was Feynamonavitchinsky or something). They came from Minsk.

And, my sister tells me, he later brought over two brothers, who on their arrival took the same new name, Feynman! That is all we know—we don’t know the first name of Jacob’s brothers or brother. Could it be Harry? If so, I am the grandson of your great grandfather’s brother. My daughter, Michelle, is 16.That would mean that you and she have the same great great great grandfather.

Anyway, we must be related somehow—and if we can’t prove it, let’s assume it—it is more fun that way.

So we are all waiting to see you when you get out here on your teen tour. Please call us when you know when you are coming, our number is [withheld].

Your relative (probably),

Richard P. Feynman

P.S. By the way, our name is all over the place on a new book, Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman, published by Norton.

Unfortunately, we were out of town when Debbie Feynman came to California and were unable to meet her.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO ROBERT L. KAMM, JULY 19, 1985

Robert L. Kamm arrived at Princeton the same day Feynman had, and he had also worked with him at Los Alamos during the war. “I ate with you at Princeton Graduate College,” he recalled. “I was at Mrs. Eisenhart’s party when she offered you cream and lemon for your tea.” With these and other memories prompted by Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman, Kamm wrote of his wife, Jane, being badly reprimanded by the chiefs at Los Alamos for leaving her door and safe open. He believed Feynman might owe her an apology.

Dr. Robert L. Kamm

Birmingham Psychiatric & Medical Associates

Southfield, Michigan

Dear Bob:

Thanks for your letter—it was good to hear from you and I enjoyed your reminiscences. But I’m afraid your mystery is still not solved, because I would never have left a safe open, or a door. I would open the safe, put a note in, but always close it up again. I had great respect for all the material and would never have done anything that would leave it available for theft. My pranks were meant to point out the need for greater security.

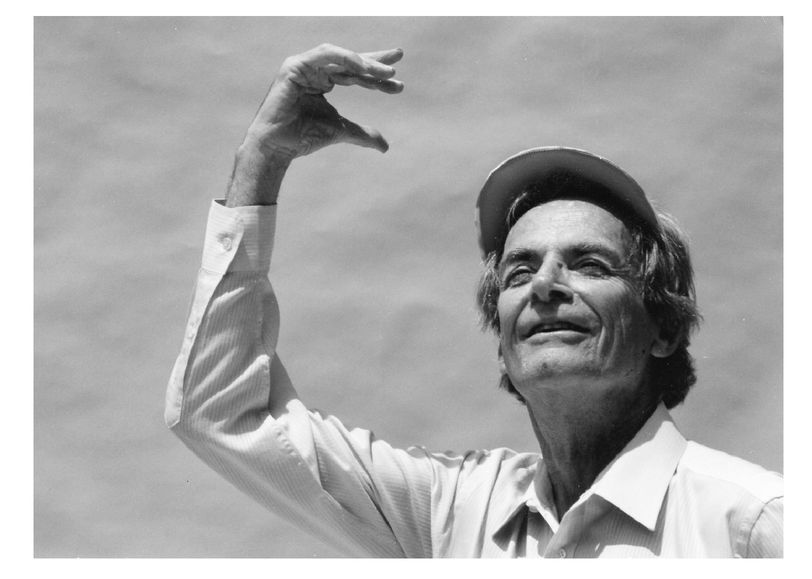

With Carl on the beach, 1985.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO DANIEL E. KOSHLAND, JR., SEPTEMBER 3, 1985

Feynman was asked by Dr. Koshland of Science magazine to give his perspective on the new theories on “strings.”

Dr. Daniel E. Koshland, Jr.

Science

Washington, D.C.

Dear Dr. Koshland:

Please accept my apology for the delay in replying to your letter of June 17; I have been out of the office since the 1st of June. However, my response to your request for an article on “strings” is that I don’t believe in them, but then I haven’t studied them well enough to know why I don’t believe in them. Such prejudice would not make an appropriate article.

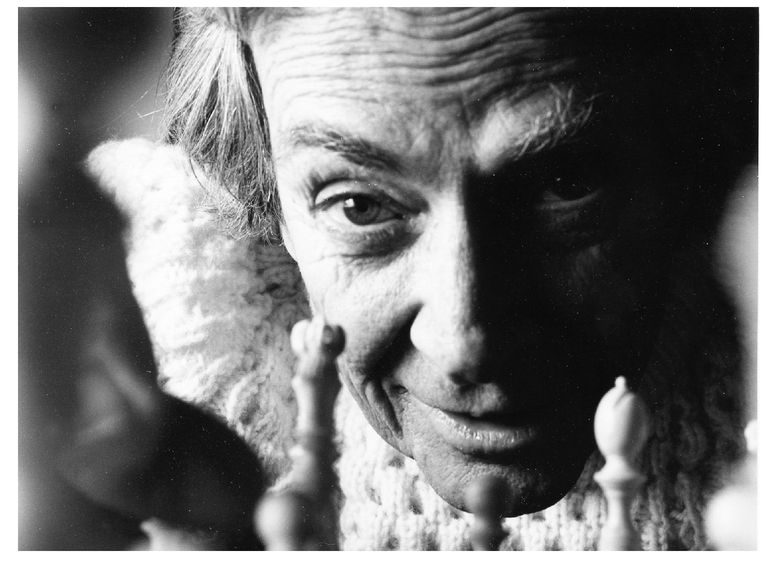

Richard and Gweneth’s Silver Wedding Anniversary, September 1985.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO MRS. HARRY GARVER, SEPTEMBER 3, 1985

Mrs. Harry Garver was another of Feynman’s longtime secretaries. I was in high school—eleventh grade—at the time of my father’s response to her letter.

Mrs. Harry Garver

Oroville, California

Dear Bette:

Thank you for writing—it was nice to hear from you. I’m gray-haired but not a grandfather—my kids are slow.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO BERNICE SCHORNSTEIN, SEPTEMBER 5, 1985

“In any case, there was a party, you and she and Florence walked home arm in arm down the middle of the street, singing at the top of your lungs. My mother thinks you ‘probably wouldn’t’ remember her, tho from photographs of that era I don’t see how anyone could forget her.” Mrs. Pauli Carnes, daughter of Bernice Schornstein (née Lesser), wrote to remind Feynman of this friend from long ago.

Mrs. Schornstein also wrote, asking for an autograph for her cousin’s son.

Mrs. Bernice Schornstein

Scottsdale, Arizona

Dear Bernice:

Of course I didn’t remember you very well from the few clues left in your letter—but your daughter supplied a few others and now I remember two beautiful teasers, each successively going upstairs to “get into something more comfortable” while I was held down by the other.We certainly had a great time, me, you and your cousin Florence.

It seems that the spirit of fun and good humor I admired that day has reappeared in your daughter—who was careful to assure me that I need not be alarmed by receiving a letter from her, as she greatly resembled another man she knew as “daddy.” Apparently she is left with the impression that we went much further than we did—times have changed, we should have been born later.

Sure, I’ll be glad to sign the book for your cousin’s son. What a nice memory to be reminded of!

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

DR. KLAUS STADLER TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, OCTOBER 4, 1985

Dear Professor Feynman,

Today I would like to introduce myself as the editor responsible for the German edition of your book “Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman.” The Piper Verlag is very glad to have got the German rights of your book.Your colleague in Munich, Professor Harald Fritzsch, was very much involved in the discussion about the book. If you have no objections I will ask Harald Fritzsch to write a preface for the German edition.

Professor Fritzsch also advised us to abridge the book a little bit. He thinks that some parts are not so important for the German reader. In the next days I hope to get a list from him with suggestions for several cuttings. Today I want to ask you to give us permission for minor cuttings. Of course I will send you the list with Professor Fritzsch’s suggestions as soon as possible.

Recently we got the information about your new book, Q.E.D., which will be published by Princeton University Press. During my stay at the Frankfurt Book Fair I am going to contact Princeton University Press. I hope to get an option for the German rights.

Do you have any other plans for publications, which would fit into our list of science books? I would be very glad to hear about your plans.

A last question for today: Is there a chance of your coming to Germany, when the German version of Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman will be published? Couldn’t that be combined with a lecture at one of the universities or Max-Planck-Institutes?—We intend to publish the book in fall ’86.

I look forward to hearing from you.

With kindest regard,

Sincerely yours,

Klaus Stadler

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO KLAUS STADLER, OCTOBER 15, 1985

Dr. Klaus Stadler

Wissenschaftliches Lektorat

R. Piper Verlag

Munich,West Germany

Dear Dr. Stadler:

Your letter about my book SurelyYou’re Joking. . . suggests that some parts might be cut out as not being so important to a German reader.

This shows a complete misunderstanding of the nature of my book.There is nothing at all in it that would be “important” to a German reader, or to any other reader for that matter. It is not in any way a scientific book, nor a serious one. It is not even an autobiography. It is only a series of short disconnected anecdotes, meant for the general reader which, we hope, the reader will find amusing. There should be no pretense of importance. Please.Your advertising should make this clear—otherwise there will be bad reviews by readers who have been disappointed. (Many reviews here have been very good—nearly all the bad ones were by people who expected more and were disappointed.)

I should have been much happier if you gave the book to a department dealing with more general books rather than “Wissenschaftliches Lektorat,” and to a translator known for his sense of humor and a healthy disrespect for pompousness and “importance” so that he would be more attuned to the character of the book. Science it is not! Naturally, the book might be improved if some parts were cut out, but for some reason other than they lack importance. Otherwise everything should be cut out.

The new book you mention, QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter, is an entirely different matter. It is a serious scientific book intended for the (very) intelligent layman or the young person interested in finding out what advanced physics is like. I am very happy to hear you are interested in it.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO EDWARD TENNER, NOVEMBER 14, 1985

In a March 21, 1985, letter regarding the promotional copy for QED, Princeton University Press assured Helen Tuck, Feynman’s secretary, that no reference would be made to Feynman’s status as Nobel Laureate. “Additionally, we have removed the reference to his ‘legendary humor.’” There remained other kinks to be worked out before publication, however.

Mr. Edward Tenner

Princeton University Press

Princeton, New Jersey

Dear Mr.Tenner:

Dr. Mautner showed me the cover for my new book “QED.”

It is truly beautiful and dignified. I am very pleased, as is everyone I show it to. It has class, they say. (To be frank I must add that when they find an advertisement for another book on the inside flyleaf, they are surprised and think that is a bit low class. I don’t know, for I don’t know what is customary, and I know and like Rudy Peierls. But I hope you don’t describe my book on anybody else’s cover!)

I am glad to see it coming out now. I am very curious as to what the reception will be. How understandable it is, really. It is hard for me to tell.

Thank you.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

Mr. Tenner wrote back to give credit to Mark Argetsinger, the book’s designer. He also assured Feynman that the notice of Peierls’s Bird of Passage would be removed from future printings, and he would let the production department know that Feynman did not want his own book imposing on the flap copy of others.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO JAMES T. CUSHING, OCTOBER 21, 1985

Professor Cushing sent Feynman a preliminary draft of a paper on Heisenberg’s S-Matrix program.

Professor James T. Cushing

Department of Physics

University of Notre Dame

Dear Professor Cushing:

I read your interesting historical paper on the S-Matrix, but I have nothing to add or comment. I had always thought that the S-Matrix program of Heisenberg’s was of relevance for the subsequent work.

By the way, I always find questions like that in your last sentence odd. It seems to me that the answer is: if Heisenberg had not done it, someone else soon would have, as it became useful or necessary. We are not that much smarter than each other. (Except perhaps Einstein’s general theory—or was Hilbert already hot on the trail, independently? I don’t know history too well. When do you think it might have been invented if there were no Einstein?)

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

STEPHEN WOLFRAM TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, SEPTEMBER 26, 1985

In the early 1980s, Stephen Wolfram turned his energies from traditional areas of fundamental physics to creating the new field of complexity research. Some physicists and science administrators were skeptical about this new direction.

Dear Feynman,

First, thanks very much for your letter on the cryptosystem. I managed to break my addiction to studying the thing for a while, but am now getting back to it. I would like to try and understand systematically how far one can get with the kind of approach you were using: in particular, whether it allows the seed to be found in polynomial time. But I must say I am still reasonably confident that the system is at least hard to break. I have a new idea for showing that breaking it would be equivalent to solving an NP-complete problem; I’ll let you know if this works out.

I thought I would send the enclosed stuff that I have just written. It is not about science (which is what I would prefer to write about), but rather about the organization of science. I am being treated increasingly badly at IAS, and really have to move. I can’t see anywhere that would really be nice to go to, and would support the kinds of things I am now interested in. So

I am thinking of trying to create my own environment, by starting some kind of institute. It would be so much nicer if such a thing already existed, but it doesn’t.There are a few plans afoot to create things perhaps like this, but I think they are rather misguided.You probably think that doing something administrative like this is an awful waste of time, and I am not sure that I can disagree, but I feel that I have little choice, and given that I am going to do it, I would like to do it as well as possible. Any comments, suggestions, etc., that you might have I would very greatly appreciate.

Best wishes,

Stephen Wolfram

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO STEPHEN WOLFRAM, OCTOBER 14, 1985

Dear Wolfram:

1. It is not my opinion that the present organizational structure of science inhibits “complexity research”—I do not believe such an institution is necessary.

2. You say you want to create your own environment—but you will not be doing that: you will create (perhaps!) an environment that you might like to work in—but you will not be working in this environment—you will be administering it—and the administration environment is not what you seek—is it? You won’t enjoy administrating people because you won’t succeed in it.

You don’t understand “ordinary people.” To you they are “stupid fools”—so you will not tolerate them or treat their foibles with tolerance or patience—but will drive yourself wild (or they will drive you wild) trying to deal with them in an effective way.

Find a way to do your research with as little contact with non-technical people as possible, with one exception, fall madly in love! That is my advice, my friend.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

Wolfram did not follow Feynman’s advice. Not only did he establish an institute but he also founded the company Wolfram Research, makers of the widely used Mathematica software system. Contrary to Feynman’s expectations, Wolfram has been a successful CEO for many years. Within this environment he has managed to pursue ambitious directions in basic science, particularly through his 2002 book A New Kind of Science. He has also been happily married since the early 1990s.

THOMAS H. NEWMAN TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, NOVEMBER 11, 1985

In autumn 1985, electrical engineering professor R. Fabian Pease at Stanford University and his graduate student Thomas H. Newman informed Feynman that they were ready to claim the first prize offered in his 1959 “There is Plenty of Room at the Bottom” challenge. In the following letter and documents, they provided information about their achievement.

Professor Feynman,

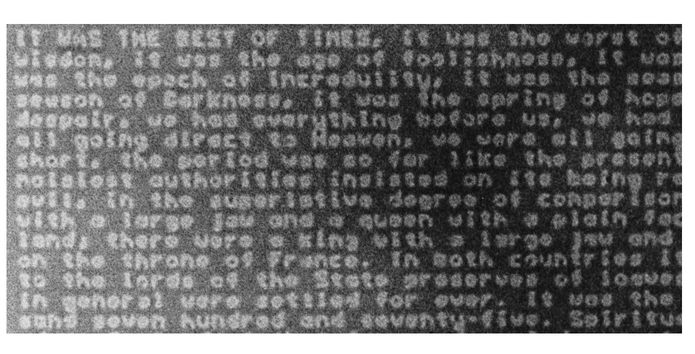

The photos enclosed are additional TEM pictures of the page of text we reduced 25,000 times in linear scale. By now you probably have reviewed the original pictures.We can supply verification of the scale on the contact prints if you want this. The TEM magnification is calibrated to within 10 percent; this accuracy could be improved by taking a picture of a TEM calibration standard at an identical magnification and then comparing the negatives side by side.

Attached is a description of the procedures we used for sample preparation, exposure and development, and inspection. Please let us know if you would like any additional supporting documentation.

Thomas H. Newman

R. Fabian Pease

Stanford University

Stanford, California

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO THOMAS H. NEWMAN, NOVEMBER 19, 1985

Dr.Thomas H. Newman

Stanford University

Stanford, California

Dear Dr. Newman:

Congratulations to you and your colleagues.You have certainly satisfied my idea of what I wanted to give a prize for. Others have apparently made as small or smaller marks, but no one tried to print an entire page. And on a 512 x 512 dot printer! Each dot is only about 60 atoms on a side. I can’t quite manage to imagine the square 1/160 mm on a side onto which all that is printed. It would be 20 times too small on a side to see with the naked eye. Only ten wave lengths of light. The entire Encyclopaedia Britannica, perhaps 50,000 to 100,000 pages of your size would be on less than 2 mm on a side—the head of a small plain pin.

Your description of the square silicon nitride windows was a bit incomplete. How big are the windows? Is each window a page, or (less probably?) a letter? Can application to computers be far behind?

As promised long ago, I am enclosing a check for $1,000 for your accomplishment.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

So concluded an important chapter in the early history of nanotechnology.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO MICHAEL ISAACSON, DECEMBER 20, 1985

Dr. Michael Isaacson

Physics Department

Cornell University

Ithaca, New York

Dear Dr. Isaacson:

It seems I let you down. I told you there was no more prize.

I knew of your work, of course, and it always interested me. Tom Van Sant is my personal friend and he told me of what you did for him. I have often talked on small things and exhibited a slide of that wonderful eye of yours as the smallest artist’s drawing ever made.

When I received an entire page from Stanford I was so delighted I sent them the prize even though I knew people had made things smaller. I forgot that I had explicitly told you there was no prize.

That is a hell of a way to run a railroad! I guess I am not a railroad man.

The first time I was interviewed, after Stanford announced it, I told them others had made things still smaller, mentioned that you and Van Sant made an eye together, but that this was the first full page of text I had seen. They didn’t print the complete interview.

Well, Merry Xmas. I am enclosing a Christmas present for you. To encourage you to continue your good work.

Your friend.

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO JOAN T. NEWMAN, NOVEMBER 10, 1986

Joan Thomas Newman, the mother of the Thomas Newman who won the tiny writing prize, wrote Feynman to express her appreciation and gratitude: “Thank you for encouraging creativity in your own mind and in the minds of your students and readers.” Although she herself had never delved into the domain of physics, she was immensely proud of her son and his accomplishments (“winning your award could not have happened to a better person”).

Dear Mrs. Newman:

Well, what a pleasant surprise to get a letter of appreciation from the parents of a scientist. I am glad to hear of how it looks from the point of view of his proud mother, who really doesn’t understand what he is doing. I know. I had a wonderful proud mother who never understood what I was doing either. How could “breaking my head” be fun? And how can Tom, working so hard in the laboratory, be having fun? But her support made my accomplishments possible—and I am sure it is the same in your family.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO ARMANDO GARCIA J., DECEMBER 11, 1985

On September 18, 1985, Mr. Amando Garcia J., a teacher in a high school in La Victoria, Venezuela, sent Feynman a five-page, single-spaced, typewritten letter, seeking help in answering an objection to the law of energy conservation, posed by twins who had been in a class he taught. Mr. Garcia had been revered by the students in his school before he failed to give a satisfactory answer to the twins’ objection. “The issue became a debate in class for weeks,” Mr. Garcia wrote, “taking us nowhere; my class lost its traditional prestige. . . . Some of my ex-students still drop by once in a while and ask me with irony: ‘have you solved the twins’ objection yet?’”

The twins’ objection had to do with a man who lowers a weight (for example, a heavy barbell) from overhead to the ground. The law of conservation says that the weight’s large potential energy must be converted into some form of energy inside the man—that is, the weight must do work on the man’s muscles as he lowers it. However, everyday experience says this cannot be so. We know from experience that the man’s muscles actually have to do work on the weight in lowering it rather than vice versa, so energy cannot be conserved. Mr. Garcia cited another example: we know from experience that when a man climbs up stairs and then descends, his muscles must do work in both the up trip and the down, but energy conservation says they should do work only going up, not going down.

Mr. Garcia pleaded with Feynman to explain how to reconcile these everyday experiences with the law of energy conservation.

Mr. Armando Garcia J.

Aragua,Venezuela

Dear Mr. Garcia:

Thanks for your letter and its questions about energy.

Your trouble comes from dealing with an open system like a man who is sweating, breathing in and out (heating air and changing some O2 for CO2) digesting food, etc., and moving about doing (or having done on him) mechanical work.To find the total energy change after some operation we would have to measure all kinds of things to access the net energy change.We must include the heat to the air, the chemical energy change in the changed air gasses, the change in the amount or form of the partly digested food, the energy difference of the form of the water sweated (from liquid to vapor), the change in energy from the shift in position of weights moved, etc. This last, the mechanical part is numerically a very small amount compared to the other changes.

So nobody can, without careful check and measurement, demonstrate that the total energy of the system has changed (or changed by amounts not accounted for by flow of energy as heat or chemicals in or out). Attention to just the tiny mechanical contributions plus or minus for a man working is completely insufficient. Observations that it seems to be a similar effort to lower or to raise a weight are insufficiently accurate—they both are efforts with large energy expenditures (to heat, change in body chemistry, etc. etc.) only differing slightly by the small mechanical differences—too slightly to be noticeable.

(For some numbers, we are expending [to keep warm and move about] about 100 watts from our food combining with oxygen.) You can check this because in one day that is 100 x 86400 sec ˜107 joules ~ = 2300 kilo calories = 2300 food “calories” because one food calorie is 1000 physics calories, and people consume around two thousand food calories a day. Now suppose a man lifts 10 kilograms up one meter. He has done 10 x 1 x 9.8 = 100 joules of work. But this amounts to the average energy to stay alive (100 watts) for only one second.

That is why we do not so directly feel the difference of going up and down stairs (but we all do, do we not, admit that it would be easier to go down many stairs than up).

To get accurate we must measure all the energy in and out over a long enough period, say one full day, breakfast to breakfast, so we can assume the animal is in about the same condition internally before and after.We can do that with animals, like rats, by monitoring all their gasses in and out and food intake.When this is done it is found to check out.

In fact it was by such experiments on animals that the law of conservation was discovered in the first place. It was done by a Doctor Mayer. Much more accurate measurements on simpler physical and chemical systems have continued to confirm it. Today we can see it work for individual atomic collisions, and since more complex systems are the results of hosts of such collisions, it ought to work there too.

Your twins may claim it is wrong by qualitative arguments about how things seem to feel. But if they test their claim with measurements made carefully enough to check for inadvertent outputs or inputs or permanent changes in the objects inside, they will find, I think, what Dr. Mayer first found, and what others have since found, that energy is indeed conserved. The consumption of O2 is higher when lifting than when releasing weights.

Your examples of times when the law was doubted (such as by Rohr) are good. There is no harm in doubt and skepticism, for it is through these that new discoveries are made. The doubts can, and therefore must, be tested and resolved by experiment. It is true that energy is a scalar quantity, like temperature, that has no direction. But measured from some arbitrary level it can be either plus or minus—surely the changes have a sign. In lifting a weight the weight’s energy is increased (and the rest of the world’s decreased) and in lowering it the signs are reversed.

I judge from your letter that in Venezuela you are teased badly if you are a professor and say you don’t know or are not sure. I am glad that I am not so teased because I am sure of nothing, and find myself having to say “I don’t know” very often. After all, I was born not knowing and have only had a little time to change that here and there. It is fun to find things you thought you knew, and then to discover you didn’t really understand it after all. My students often help me do that (for example, by bringing up apparent difficulties like your twins did). And then they have to help me finally understand it better.

Anyway, I hope this helps some. Good luck to you and your students, teaching each other.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO L. DEMBART, JANUARY 15, 1986

Mr. L. Dembart

Science Writer

Los Angeles Times

Los Angeles, California

Dear Mr. Dembart:

Thank you for mentioning my name in your editorial. If you have no intention of writing a longer article, would you please consider the following letter for the “Letters to the Editor” page?

“You reported in an editorial ‘The Wonder of It All’ about a proposal to explain some small irregularities in an old (1909) experiment (by Eötvös) as being due to a new “fifth force.”You correctly said I didn’t believe it—but brevity didn’t give you a chance to tell why. Lest your readers get to think that science is decided simply by opinion of authorities, let me expand here.

If the effects seen in the old Eötvös experiment were due to the “fifth force” proposed by Prof. Fischbach and his colleagues, with a range of 600 feet it would have to be so strong that it would have had effects in other experiments already done. For example, measurements of gravity force in deep mines agree with expectations to about 1% (whether this remaining deviation indicates a need for a modification of Newton’s Law of gravitation is a tantalizing question). But the “fifth force” proposed in the new paper would mean we should have found a deviation of at least 15%.This calculation is made in their paper by the authors themselves (a more careful analysis gives 30%). Although the authors are aware of this (as confirmed by a telephone conversation) they call this “surprisingly good agreement,” while it, in fact, shows they cannot be right.

Such new ideas are always fascinating, because physicists wish to find out how Nature works. Any experiment which deviates from expectations according to known laws commands immediate attention because we may find something new.

But it is unfortunate that a paper containing within itself its own disproof should have gotten so much publicity. Probably it is a result of the authors’ “over-enthusiasm.”

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

This letter was subsequently published in the Los Angeles Times.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO GWENETH AND MICHELLE FEYNMAN, FEBRUARY 12, 1986

The following letter was written during Feynman’s stint on the presidential commission investigating the Challenger Space Shuttle accident.

Wash.Wed. Feb

2 P.M.

Excuse the paper, I can’t find hotel stationary.

Dearest Gweneth and Michelle,

This is the first time I have time to write to you. I miss you, and may figure out later how I can get a day off and visit (when a very boring meeting is scheduled?). This is an adventure as good as any of the others in my book.You, Gweneth, were quite right—I have a unique qualification—I am completely free, and I there are no levers that can be used to influence me—and I am reasonably straight-forward and honest.There are exceedingly powerful political forces and consequences involved here, but altho people have explained them to me from different points of view, I disregard them all and proceed with apparent naïve and single-minded purpose to one end, first why, physically the shuttle failed, leaving to later the question of why humans made apparently bad decisions when they did.

As you know, Monday at home at 4 P.M. they told me I was on the committee and I should fly in (Tuesday night) for a Wednesday meeting. All day Tuesday I educated myself with the help of Al Hibbs and technical guys he brought around to help me (I knew nothing about the shuttle considering, before, that it was some sort of boondoggle). I was preparing myself technically for the job, and the preparation was excellent—I learned fast.

We had an “informal get together” on Wed. when we were advised by the Chairman on how important press relations were, and how delicate.We had a public meeting Thurs February 5th which used up the whole day, the entire committee being briefed on facts about the Challenger and its flight. I spent the night making a plan of how I—and we should proceed—facts to get—a long list of possible causes—make some calculations of loads and so on and so on, ready to roll.

Fri February 6th, a General Kutyna on the commission tells us how such accident investigations have been made in the past—using a Titan failure for an example.Very good. I was pleased to see that much of my plans of February 5th are very similar, but not as methodical and as complete. I would be happy to work with him, and a few others want to do that too—others suggest they could make better contributions by looking into management questions, or by keeping records and writing the report, and so on. It looks good. Here we go.

But the Chairman (Rogers, not a technical man) says that the General’s report cannot serve for us because he had so much more detailed data than we will have (quite patently false—because of human safety questions very much more was monitored on our flight!) Further it is very likely that we will be able to figure out just what happened (!?), and the co-chairman says the commission can’t really be expected to do any detailed work like that—we shall have to get our technical advice from mutter mutter. I am trying to get a word in edgewise to object and disagree but am always interrupted by a number of accidents, someone just comes in to be introduced around, the chairman returns to a new direction, etc. What is decided is that we, as an entire committee will go down next Thursday to Kennedy to be briefed by people there on Thurs, Fri. During the discussion earlier there are various pious remarks about how we as individuals or better small groups (called subcommittees) can go anywhere we want to get info. I try to propose I do that (and several physicists tell me they would like to go with me) and I have set my affairs so I can work intensively full time for a while. I can’t seem to get an assignment, and the meeting breaks up practically while I am talking—with the Vice Chairman’s (Armstrong) remark about our own not doing detailed work. So on leaving I say to the chairman, “then I should go to Boston for a consulting job there for the next five days (Sat, Sun, Mon, Tues, Wed)?” “Yes, go ahead.” I DON’T HAVE TO EXPLAIN TO YOU WHY THAT DRIVES ME UP THE WALL!

I leave, very dejected. I then get the idea to call Dr. Graham head of NASA who had been my student and who had asked me to serve. He is horrified, makes a few calls and suggests possible trips to Houston (Johnson Airforce Base where the telemeter data comes in) or Huntsville Alabama (where they make the engines). (I turn down Kennedy because we shall go there later and it is too direct a rebellion from the chairman.) To get the chairman to OK this he calls commissioner (a lawyer, son of Dean Acheson, a good friend of Chairman Rogers). Acheson says he will try, as he thinks it is a good idea. Calls back surprised he can’t get OK—chairman doesn’t’ want me to go,“We want to do things in an orderly manner.”

Graham suggests compromise. I will stay in Washington, and even tho it is Saturday he will get his men (high level heads of propulsion, engines, orbiter etc.) to talk to me. That seems to be OK altho I get a call from Rogers trying to bring me to heel—explaining how hard his job is organizing this—how it must be done in an orderly manner etc.—do I really want to go to NASA (“Yes”). I point out so far two meetings and still no talk on how we should proceed, who can best do what etc. (Most of the talk at the meeting was by Rogers, on how he knows Washington, that there are serious questions of orderly press relations—tell any reporter he should go to him, Rogers, for answers etc.). He asks me if he should bother all the commissioners and ask them to come to a meeting Monday which he will convene. “Yes,” I say. He drops that subject—OK’s that I stay in Washington and suggests, “I hear that you are unhappy with your hotel—let me put you into a good hotel.” I don’t’ want any favors, tell him no everything is OK, that my personal comfort is less important to me than action, etc. He tries again, I refuse again (Reminded of “Serve him tea” at London airport).

Giving testimony for the Presidential Commission for the Challenger Space Shuttle Accident, 1986.

So Saturday I got briefed at NASA. In the afternoon we talk in fine detail about joints and O-rings, which are critical, have failed partially before and may be the cause of the Challenger failure. Sunday I go with Graham and his family to see the air and space museum which Carl liked so much—we are in an hour before the official opening and there are no crowds—influence; after all, the acting head of NASA.

All this time evenings I eat with or go over to the house of Frances and Chuck. It is a very welcome unwinding, but I don’t tell stories because they are with the press and I don’t want to spread or be suspected of spreading leaks. I report to Rogers that I have these close relations with press connections and is it OK to visit with them? He is very nice and says,“Of course.” He himself had some AP connections, he remembers Frances, etc. I was pleased by his reaction but now as I write this I have second thoughts. It was too easy—after he explicitly talked about the importance of no leaks etc. at earlier meetings. Am I being set up? (SEE DARLING, WASHINGTON PARANOIA IS SETTING IN). If, when he wants to stop or discredit me, he could charge me with leaking something important. I think it is possible that there are things in this that somebody might be trying to keep me from finding out and might try to discredit me if I get too close. I thought I was invulnerable. Others like Kutyna, Ride, etc. have some apparent weakness and perhaps may not say what they wish. Kutyna has Air Force interests to worry about. Ride, her job at Johnson Air Force Center, etc., etc. But, as I learned, I must keep watching in all directions—nobody is invulnerable—they will sneak up behind you. So, reluctantly, I shall not visit Frances and Chuck anymore.Well, I’ll ask Fran first if that is too paranoid. Rogers seemed so agreeable and reassuring. It was so easy, yet I am probably a thorn in his side.

Anyway, Monday and Tuesday we have a special closed and open meeting respectively because some internal reports saying the joint seals are or might be dangerous appear in the NY Times. Big deal. I knew all the facts in question—I got them at JPL before I started.Very important emergency concerning press relations! At this rate we will never get down close enough to business to find out what happened. Not really—for now tomorrow at 6:15 we go by special airplane (two planes) to Kennedy Space Center to be “briefed.” No doubt we shall wander about being shown everything—gee whiz—but no time to get into technical detail with anybody. Well it won’t work. If I am not satisfied by Friday I will stay over Sat and Sun, or if they don’t work then Monday and Tuesday. I am determined to do the job of finding out what happened—let the chips fall!

I feel like a bull in a china shop.The best thing is to put the bull out to work the plow. A better metaphor will be an OX in a china shop because the china is the bull, of course.

My guess is that I will be allowed to do this overwhelmed with data and details, with the hope that so buried with all attention on technical details I can be occupied, so they have time to soften up dangerous witnesses etc. But it won’t work because (1) I do technical information exchange and understanding much faster than they imagine, and (2) I already smell certain rats that I will not forget because I just love the smell of rats for it is the spoor of exciting adventure.

So much as I would rather be home and doing something else, I am having a wonderful time.

Ralph

24 called me this morning from Sweden to report amazing progress. Christopher Sykes is involved. He comes back next Wednesday and will tell you all about it.TUVA OR BUST!

Love,

Richard

P.P.S. Save the newspapers. I was at the Pentagon this morning—and they sent you clippings of the NY Times.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO WILLIAM P. ROGERS, SATURDAY, MAY 24, 1986

Dear Mr. Rogers,

I am very sorry I had to leave at noon Saturday, before we had time to discuss fully the problem that our report might seem overly critical of the NASA shuttle program. I would like to explain my views in more detail.

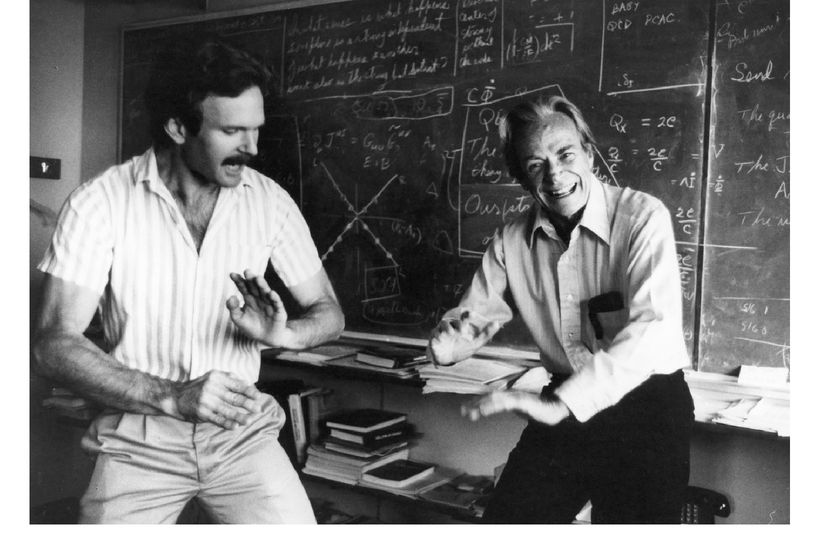

Feynman and good friend Ralph Leighton, 1987.

It is our responsibility to find the direct and proximate causes of the accident, and to make recommendations on how to avoid such accidents in the future.

Unfortunately we have found, as the proximate cause, very serious and extensive “flaws” in management. Not just a crack but a general disintegration. Our report lists them with our evidence for our view.

This raises serious problems for our nation as to how to continue on with the space program. There are very large questions of budget, what other projects to follow to supplement the shuttle ( i.e., Expendables?) to maintain a scientific and more importantly, military strength, commercial space applications, etc. Our entire position and program in space must be reconsidered by people, Congress and the President. We did not discuss these matters—and make recommendations in this larger theater.We were asked, as I see it, to supply information needed to make such decisions wisely.

It is our duty to supply such information as completely, accurately, and impartially as possible.We have laid out the facts and done it well.The large number of negative observations are a result of the appalling condition the NASA shuttle program has gotten into. It is unfortunate, but true, and we would do a disservice if we tried to be less than frank about it. The President needs to know if he is to make wise decisions.

If it appears we have presented it in an unbalanced way, we should give evidence on the other side. Let us include somewhere a series of specific findings that this or that is very good, or recommendations that they keep up the good work in this and that project specifically. One example is the software verification system. I think, altho I seem to be pollyanna and a little dumb—I thought (apparently incorrectly?) that NASA was very helpful and courteous in giving us all the information (and doing tests) we asked for, especially in our accident panel.

A general statement, without presenting the particular evidence in the report, that NASA is after all actually doing a wonderful job would weaken our careful report, and might even make us look foolish, if it contrasted with the mass of evidence we ourselves present in a careful documented way.

Well, I’ll be back Monday and we can discuss it with other commissioners more fully next week. Maybe they may explain to me where my point of view is off base and I will change my mind—now I doubt it of course. I feel very strongly about this now.

I am satisfied that my “Reliability” contribution need not go in the main report but will go into the appendix more or less intact rather than being lost in the archives. It is a good compromise we have come to.

See you soon,

Commissioner Feynman, Nobel Prize, Einstein Award, Oersted Medal and utter ignoramus about politics.

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO DAVID ACHESON, DECEMBER 5, 1986

Fellow commissioner David Acheson wrote a note to Feynman, sending news of other commission members. He had also heard of Feynman’s illness and sent earnest wishes for a whole and speedy recovery.

Mr. David C. Acheson

Washington DC

Dear Dave:

Thank you very much for the note with all the news.

I’m recuperating slowly at home. I also hope I see you again sometime, but nothing short of a subpoena from Congress will get me to Washington again.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO JOHN W. YOUNG, DECEMBER 8, 1986

Dr.Young wrote to express appreciation for Feynman’s part in the Challenger accident investigation. “We realize this was an extremely difficult task: technically, physically, and emotionally.Your report is thorough and insightful and will help lead NASA back to safe flight.You have done a great service for the Astronaut Office and the Nation.”

Dr. John W. Young

Chief, Astronaut Office

NASA

Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center

Houston,Texas

Dear Dr.Young:

Thank you for your compliment about my work on the Challenger investigation.

I’m sorry I didn’t get time to discuss matters with the astronauts more directly and informally and to meet you. We had a division of labor, and I depended on Dr. Sally Ride to give us your opinions, as she did.

I was particularly impressed by the careful analysis exhibition in the testimony of Mr. Hartsfield, yourself, and the other astronauts during one of our public meetings. It seemed that you were the only people thinking about the future, and the causes of things in a clear way. It soon became apparent that the testimony of higher management was a bit muddleheaded about why they weren’t told, why the system broke down, etc.They weren’t told because they didn’t want to hear any doubts or bad news.They were often involved in justifying themselves to the public and Congress—so the correct thing for lower-level bureaucrats was clear—solve it yourself, or at least don’t rock the boat. Like the Wizard of Oz, NASA had a great reputation to maintain, but when a few screens were knocked over, it was seen to be imperfect.

I hear the same thing is happening again—complex questions being hidden in innocuous little “bullets,” so even the joint-certifying committee is having trouble getting information.

Is there anything you astronauts can do to clean the Augean stable?

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO GENERAL DONALD J. KUTYNA, DECEMBER 8, 1986

The Cook report made claims that the Presidential Commission on the Challenger Space Shuttle Accident was engaged in a cover-up of the government’s involvement in launch decisions, hid many of its findings, and helped NASA personnel perjure themselves.

Major General Donald J. Kutyna

San Pedro, California

Dear Don:

Thanks for sending me the information about the “Cook report.” I suppose it is to be expected that some problem like this would come up. Of course it is true that some criticism is sensible, and there are always paranoids waiting for their chance to criticize every investigation.You are right in that we didn’t do a perfect job, but of course if the Chairman had listened to us it may have been closer to perfect. After all, it has been said that the last perfect person was crucified.

Do you believe “there is evidence that not only did NASA personnel perjure themselves before the Commission, and that in closed sessions the Commission actually advised them to do so and helped to concoct their stories,” as reported in that article?

I’m recovering pretty nicely from my surgery, and I hope we can arrange to get together soon.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

General Kutyna told me that Mr. Richard C. Cook, former NASA resource analyst and author of this report, had discovered something interesting prior to Challenger’s launch: “a NASA action to add money to the budget to fix the O-Rings.”NASA was concerned about the impact to flight safety that the O-RING anomalies might potentially pose, but were not totally open relative to these concerns. However, the General saw absolutely no instances of perjury. Mr. Cook misinterpreted NASA’s silence as a Comission cover-up, which it was not. The Comisssion found out about NASA’s omission during their investigation, and Feynman’s Appendix F of the Comission report details some of the missteps and motives within NASA.

General Kutyna emphasized that “the specific direction of the Commission was to find the technical cause of the accident, and not to go on a witch hunt to blame individuals.”

LEIGH PALMER TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, JANUARY 1, 1987

Dear Prof. Feynman,

My son, David, tells me that you are not well, and I am very sorry to hear that. I wanted to tell you about something that happened last semester for which you were principally responsible, and which illustrates a very strange (but avoidable) human failing, the effect of prejudice on learning.

For more than twenty years I have wanted to understand the Hanbury-Brown, Twiss “intensity interference” effect. During the last twenty years I had asked several of my colleagues to explain the effect to me in a way that I might assimilate it into my ill-adapted experimentalist brain. I don’t even know how many of those guys I asked actually “understood” the effect in the way I interpret that word. I know that their throwing around phrases like “Bose-Einstein condensation” did not lead me to enlightenment. During this period I had even taught junior and graduate level optics courses, and in several semesters statistical mechanics, including quantum statistics, which I think I understand. I had not been able to say the same, however, about Hanbury-Brown,Twiss.

Then my daughter brought me a copy of QED from the U. of Washington bookstore. (The book was not available here in Vancouver.) I read it with delight, but somewhat slowly, as I was teaching at the time, and I had only learned of the book through a review in Scientific American. My attitude was that of a physicist reading a very well-done popularization. I do not understand QED, however, so I hoped to gain some insight from the book as well. While I was following the very lucid development, filling in what I feel is a remarkably small number of “details,” and understanding what I was reading, I came across a footnote. It seems that Hanbury-Brown, Twiss had been explained to me entirely en passant. I suddenly had the rush of understanding, though I did go back and read it again to make sure.The most important part of this was that I discovered that this, at least, was an area in which I was not invincibly ignorant.

The lesson in this is clear.While knowledge is most readily assimilated by the prepared mind, that same mind can be quite refractory to penetration if it is “prepared” to believe that it cannot be taught. I have certainly had to overcome this attitude in my own students many times, but I had thought myself immune. It was very good to learn something from a master teacher after the age of fifty, when I had become convinced that I could not ever hope to understand it.You did it by explaining it to me without first letting on what it was you were about to explain! I will remember (and use) this trick for the rest of my life. It does not matter that you had no intention of doing this; what matters is that the technique is effective in the case of a strong prejudice against learning a particular topic.

My family and I will always remember fondly our all-too-brief interactions with you and with your family here in British Columbia.While our David has not had the chance to be in one of your classes at CalTech, he has learned much which must be attributed to your good influence, indirect though it may have been. I hope the New Year brings to you and your family as much peace and pleasure as possible under your difficult circumstances.

With sincere thanks,

Leigh Palmer

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO LEIGH PALMER, JANUARY 12, 1987

Dr. Leigh Palmer

Burnaby, British Columbia

Canada

Dear Dr. Palmer:

Among the greatest mysteries of learning, and teaching, must be this appearance of “blocks.”What causes them? How to get around them?

Perhaps good fortune removed your block for H.B. & Twiss but have we learned a trick to use? Perhaps our students will be turned off by a professor who “goes off explaining things, before he tells us what he is going to explain.” The trouble is in our ‘classes’ of several students, all different and thinking in different ways.What works on one loses the others.Ahh, but in the rare case that we are tutoring one on one (the only time I really felt I was really an effective teacher) then perhaps the trick may be useful. Thank you for pointing it out to me. I may find a chance to use it consciously.

I remember my visits to Simon Fraser and Vancouver with the greatest of pleasure.Thank you for helping to make it so.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO H.-J. JODL, APRIL 10, 1987

Professor Jodl wrote to Feynman asking to translate and reprint “What is Science?”

Professor Dr. H.-J. Jodl

Fachbereich Physik

Universität Kaiserslautern

West Germany

Dear Professor Jodl:

You have my permission to translate and publish the article in your journal. But the world has changed—and I made a remark about “a girl instructing another one how to knit argyle socks.” Could you add a footnote, by the author (me), to that paragraph: “How wonderfully the world has changed.Today conversations among women on analytic geometry are commonplace.”

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

NIGEL CALDER TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, JULY 2, 1987

Professor Richard Feynman

California Institute of Technology

Dear Dick,

It is with great sadness that I have to tell you that our dear friend and colleague Philip Daly is terminally ill with a brain tumour. He had an operation at the end of May, but it was too far gone for the surgeon to do very much about it.

Phil is now at home, compos mentis, and carrying on with some work on his current projects for BBC-TV on 20th Century Science and the History of Broadcasting. I have visited him twice, to help him with this work.

He knows what is wrong with him, but believes he has until the end of the year, and is talking about doing some filming in the USA in September. His wife Pat, privately and probably more accurately, interprets the surgeon’s comments as meaning weeks rather than months.

He would be very glad to hear from you I’m sure, if only by way of a brief note or a greetings card.Too strong an expression of sympathy tends to upset him, not just because of his real predicament but because the tumour is affecting his emotions.

I hope you are keeping well yourself, Dick. It was a pleasure and a privilege to meet you in Cambridge last year, and I greatly enjoyed our chat about QED even though my powers of persuasion were not enough!

With best wishes,

Yours sincerely,

Nigel Calder

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO PHILIP DALY, JULY 22, 1987

Mr. Philip Daly

Quarry Corner

Bath, England

Dear Philip:

I heard the surgeons have got to you too, like they got to me. Good luck in your recuperating period—mine was a little long and when I complained, the surgeon said he never had a patient yet who didn’t think he was recuperating too slowly. So have patience.

Are you coming to the U.S. soon? If you are near Los Angeles you are welcome to stay with us. Unfortunately we don’t plan to go to England this summer. Gweneth sends regards.

Sincerely,

Richard P. Feynman

VINCENT A. VAN DER HYDE TO RICHARD P. FEYNMAN, JULY 3, 1986

Dear Dr. Feynman:

OK, right from the start this might seem to be a strange letter. But once you see what I’m trying to do maybe it will not sound so strange. First off, I have this 16 year old son, step-son really, that is fairly bright. No genius you understand, but a lot smarter than I am in math and such. Like everybody else he is trying to figure out what life is all about.What he doesn’t know yet is that nobody ever figures out what life is all about, and that it doesn’t matter. What matters is getting on with living. So, here is this kid, bright, very good in math and chemistry and physics. Flying radio controlled model airplanes, and reading books about wing design that have a lot of equations in them that I sure don’t know how to solve.

But at the same time he’s trying to grow up and figure himself and his world out a little. A bit over weight, a little shy, not a whole lot of self-confidence. So he makes up for it by coming on a little strong, playing macho sometimes.Trying to figure out what kind of a man he’s going to be.Trying to work out how to handle high school. He’s going to be a junior come fall, so college is not far away. He’d love to get into some neat school, but with his grades the way they are that could be a problem.

Now, I don’t want to be a pushy parent.Whatever he wants to do is fine with me. I started out in electrical engineering in 1960 because my father wanted an engineer, and ended up in criminology. So I know what it’s like to be pushed around by a parent and have those expectations forced on you. All I want is that he do whatever it is he wants to do to the best of his ability. It’s almost a matter of honor in a way. If you can do something well, you have some sort of obligation to yourself to do it the best you can. I’m afraid that’s a concept not thought highly of in a lot of circles, now or ever, but how can an intelligent person live with themselves if they aren’t doing something they love to the best of their ability?

Anyhow, after talking to his teachers for the past two years a real pattern emerges. It seems that he picks all the science up fast, sees how you do a thing, and then he wants to go on as fast as he can on his own. Some of the teachers really encourage that, which is great. But... it turns out that everybody grades on the basis of how you score on the tests, and the tests only cover what they teach to everybody. Martin, that’s his name, sees the basic stuff as too easy for him and hence it’s beneath him to hand in the routine day to day assignments. He’d rather be doing the neat fun stuff that the rest of the class never gets to do.The trouble is that a lot of the grade comes from doing the routine stuff, not the exotic stuff, so his grades are down. That, of course, is a bummer. His teachers get after him, I harass him more than I should, and he feels bad. Bah and humbug all the way around. In the non-science courses it’s even worse, because he knows that a lot of the stuff is bull and indoctrination.You get the picture.

Well now. A few months ago I came across this book. Interesting (different) title and the guy on the cover looks like a standup comic, not a physicist. Both Martin and I read the book.VERY funny. But we notice almost every story has some point to it.This isn’t just a book of funny stories; it’s a book about how the world works! Clever.We also follow the news about the Challenger tragedy and the Rogers Commission. And here’s the same fellow as wrote the book, helping put NASA back on the track to the stars, and not mincing words in doing it. Great.

So I get to thinking. Here’s this guy. My kid has read his book, followed the news and all, and the guy is a Nobel Prize winner too. The sort of fellow that kids with a bent toward science look at and go WOW. And I have this “problem.” Now, you obviously know a lot about science, and if the book is any indication you know a lot about how people work too. And who knows what it is that would make a smart 16 year old kid stop for a minute and think about what it is that he really wants in his life (at least for awhile) and what it is going to take to get it. So.... Maybe you could write to this kid. Tell him what you think “about life”; what does it mean to “do science,” what do you have to do to train yourself to be whatever it is you want to be. I don’t know, tell him whatever you want to tell him. Just knowing that somebody “out there” understands and cares a little can make a big difference sometimes. It helps keep the wings straight and the nose up.Thanks.

Sincerely,

Vincent A.Van Der Hyde

PS It is a good book, hope you write another for the “popular press.”

RICHARD P. FEYNMAN TO VINCENT A. VAN DER HYDE, JULY 21, 1986

Mr.V. A.Van Der Hyde

Juneau, Alaska

Dear Mr.Van Der Hyde:

You ask me to write on what I think about life, etc., as if I had some wisdom. Maybe, by accident, I do—of course I don’t know—all I know is I have opinions.

As I began to read your letter I said to myself—“here is a very wise man.” Of course, it was because you expressed opinions just like my own. Such as, “what he doesn’t know yet is that nobody ever figures out what life is all about, and that it doesn’t matter.”“Whatever he wants to do is fine with me”—provided “he does it to the best of his ability.” (You go on to speak of some sort of obligation to yourself etc., but I differ a little—I think it is simply the only way to get true deep happiness—not an obligation—“to do something you love to the best of your ability.”)

Actually if you love it enough you can’t help it, if anyone will give you a little freedom. Even in my crazy book I didn’t emphasize—but it is true—that I worked as hard as I could at drawing, at deciphering Mayan, at drumming, at cracking safes, etc. The real fun of life is this perpetual testing to realize how far out you can go with any potentialities.

For some people (for me, and, I suspect, for your son) when you are young you only want to go as fast as far and as deep as you can in one subject—all the others are neglected as being relatively uninteresting. But later on when you get older you find nearly everything is really interesting if you go into it deeply enough. Because what you learned as a youth was that some one thing is ever more interesting as you go deeper. Only later do you find it true of other things—ultimately everything too. Let him go, let him get all distorted studying what interests him the most as much as he wants. True, our school system will grade him poorly—but he will make out. Far better than knowing only a little about a lot of things.

It may encourage you to know that the parents of the Nobel prize winner Don Glaser (physicist inventor of the bubble chamber) were advised, when their son was in the third grade, that he should be transferred to a school for retarded children.The parents stood firm and were vindicated in the fourth grade when their son turned out to be a whiz at long division. Don tells me he remembers he didn’t bother to answer any of the dumb obvious questions of the earlier grades—but he found long division a little harder, the answers not obvious, and the process fascinating so began to pay attention.