Chapter Ten: Sally May Really Cares, After All

There was one small detail about the location of my sickbed that hadn’t occurred to me: Sally May had put it in a spot that she could see from her kitchen window.

Do you realize what this meant? Maybe you don’t and maybe I didn’t either, but what it meant was that Sally May cared about my health, safety, and physical condition, even though she had gone to some lengths to hide her concern.

Consider the evidence in this case. She had not allowed me into the air-conditioned comfort of her house, right? And that was . . . well, I won’t say that it was cruel and unfeeling of her. Or heartless. Callous. Cold-blooded.

I’d be the last dog to say anything critical of my master’s wife. I know she had her priorities, and keeping her house neat and clean was high on her list—quite a bit higher than my personal health, safety, and well-being.

I understood that. I accepted her just as she was, and I’d be the last dog in the world to suggest that she was, well, cruel and unfeeling, heartless, callous, and cold-blooded.

No, you’d never catch me making critical remarks about the very lady my master had chosen with whom to share his life. With. With whom. But her weird sense of priorities probably struck YOU as being cruel, unfeeling, and so forth, and what YOU think is important.

Yes it is, and if YOU want to say that she had her priorities and sense of values all messed up and backward, there’s nothing I can do to stop you. It’s a free lunch.

A free ranch, I should say.

Freedom of speech is a precious right.

I’m sorry you feel that way about Sally May, but just between you and me and the gatepost, there’s probably more than a germ of truth in what you’ve pointed out. And you know where I stand on the issue of germs. I’m totally against ’em.

Germs are bad for everyone, and anything that’s bad for everyone can’t be all good.

And where were we? Sometimes I get started on a thought, usually a deep philosogical point, and I forget whether it’s raining or Tuesday. Actually, it was sunny and Monday, and I have no idea what . . . something about Sally May . . . boy, sometimes I . . .

Wait, I’ve got it. Okay. Here we go.

For a while there, it appeared to YOU, not necessarily to me, it appeared to YOU that Sally May was a cruel and so forth person because she had left the wounded and suffering Head of Ranch Security outside with the flies, buzzards, and boring morons such as Drover.

But what you forgot or never knew or didn’t notice was that she was observing me from her kitchen window, an indication that she really did care about me. And no doubt, she saw me in my state of misery—tormented by flies, roasted by the sun’s evil rays, racked or wracked by thirst, whichever way you spell it, and last but not leased, gazed upon and mocked by a pair of half-crazed graveyard buzzards.

You thought she was cruel and unfeeling? Had a heart of stone, and we’re talking about absolute granite? Well, hang on and stand by for this next piece of news.

No sooner had Doom and Gloom, the buzzards, departed the scene than Sally May came out of the house, passed through the yard gate, said something nice and kind and totally inappropriate to her stupid cat, hiked up the hill to the storage tank, and looked down at me.

And yes, I did rise to the occasion and did give her the Look of Maximum Woe and Misery. And thumped my tail many times. And summoned up the little groaning sound that I use only on very special occasions.

And by George, it worked!

“All right, Hank McNasty, I surrender. I hung tough on everything but the buzzards, and that was too much, even for me. Why, if someone from the church drove up . . .”

She placed her hands on her hips and leaned down, so that I couldn’t possibly miss the, yikes, stern lines on her face.

“If I let you in my house, will you act civilized?”

Oh yes, ma’am.

“Are you capable of being rational and sane and civilized for a few hours?”

Oh yes, ma’am, on my Solemn Cowdog Oath!

She raised a clenched fist. “And buddy, if you barf on my clean floors, if you chew on my sofa, if you wet on my carpet, YOU WILL . . .”

I held my breath, waiting for her to finish that terrible sentence. What would it be? Marched outside and shot? Torn to shreds and pieces? Fed to the crows? Barbecued slowly over mesquite coals?

“YOU WILL REGRET IT!”

Whew! That was an acceptable risk. I could go for that.

You bet, she had my Most Solemn Cowdog Oath that I would never, never do any of the so forth, never ever. But if I did, through some freakish act of nature, I would most certainly regret it.

With all my heart.

And soul.

And liver.

Forever.

But of course, the odds against such a thing ever happening were infantassible. Sally May was taking no risk whatsoever, almost no risk at all.

She dropped her cleansed fish, which I was very happy to see because, believe it or not, she had actually punched me in the nose on several occasions, with that very same . . .

Did I say “cleansed fish”? I meant clenched fish.

Cleansed fist.

Clenched fitch.

Her upraised hand contracted upon itself so as to form a deadly weapon, such as a club.

She dropped her cleansed fish and straightened up, much to my relief, and spoke to me in a kinder tone of voice.

“I shouldn’t do this. I know what will happen. You can’t be trusted. But what’s a poor woman to do? God gave me a heart and a conscience.” She lifted her eyes toward the sky. “Thank you, Lord . . . I guess.” Back to me. “Now, can you walk to the house or do I have to carry you?”

Well, I could have probably . . . that is, being carried sounded pretty good to me, and after all, I was in a weakened, swollen condition, and if it was all the same to her, well, being carried would be fine.

I gave her Very Sad Eyes and Slow Wags, as if to say, “Walking is out of the question, I hate to be such a burden, I really do, but maybe you ought to, uh, carry me, so to speak.”

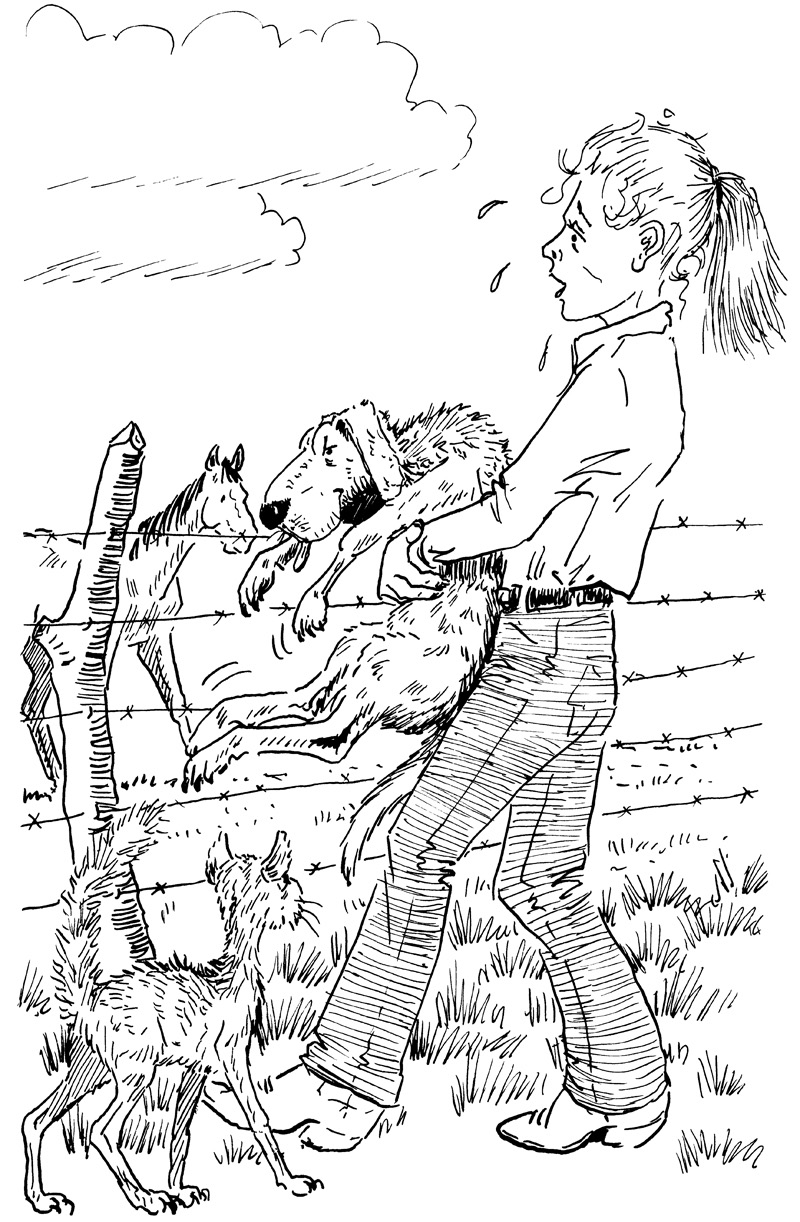

“I don’t believe I’m doing this,” she said. Then she bent over, wrapped her hands around my chest, picked me up with a loud groan, and began staggering down the hill.

I felt terrible about it.

We made it to the yard gate. There, she set me down, leaned against the gatepost, and gasped for breath.

Between gasps, she said, “How could you weigh so much?”

It was all that poison, no doubt. Rattlesnake poison is very heavy.

“Well, can you walk the rest of the way?”

I, uh, thought that one over—ran my gaze to the back door of the house and calculated the distance involved and . . . no, as much as I hated being a burden and an invalid, my old legs just couldn’t carry me that far.

Boy, I hated that.

When she’d caught her breath, she picked me up again and off we went toward the house—she staggering and grunting under her terrible burden, and I with all four legs pointed straight east.

We passed Pete the Greedy Sneaky Barncat. He watched our little procession with a look of purest envy. I gave him a little grin and said, “She loves me more than she loves you, ha ha ha.”

Oh, that killed him! Right there in the space of a few seconds, he died a thousand deaths and I lived a thousand lives, all of them happy ever after.

It was one of the greatest moments of my entire career, and the little snot deserved every bit of it for telling me lies about the rattlesnake. See, he’d been the one who had . . .

Well, I couldn’t remember every little detail of the morning’s tragedy, but I did know that it had been entirely his fault, because he had . . . something.

Yes, I feasted on his sour look, and it was as sweet as honey in the mouth of my memory.

We left Kitty-Kitty sitting in the ruins of his own shambles, and staggered down the sidewalk to the back door. There, Sally May dropped me again and more or less fainted against the side of the house, once again gasping for breath.

“I’m too old for this. I can’t nurse a dog and raise two children at the same time. Hank, I’ve carried you this far. Do you suppose you could walk the rest of the way?”

I studied on that. I would have done just about anything for Sally May, and boy, you talk about feeling guilty! But no, I sure didn’t see any way of doing that.

I mean, I was actually getting weaker by the second.

She caught her breath at last, propped the screen door open with her . . . well, with her fanny, so to speak, picked me up once again, and off we went into the utility room.

I couldn’t be blamed for the laundry basket that was parked right in the middle of our road, and no one could have been sorrier than I that she fell into it.

It was nobody’s fault, just one of those things that happen.

Little Alfred was standing in the kitchen, dripping a stolen Popsicle on the floor. He witnessed the accident and thought it was funny, the little snipe. And he started laughing.

Sally May didn’t think it was so funny. Her finger shot like an arrow toward the boy. “YOU stop dripping on my clean floor, young man, and YOU . . .” This arrow was pointed at, well, me, it seemed. “. . . can walk into the kitchen, because I’m not carrying you another step!”

Okay, okay. Fine. Sure.

I didn’t mind walking. It was the least I could do.

No big deal.

But she didn’t need to screech at me like that.

Dogs have feelings too.

Clenched fist, that’s what it was, not a cleansed fish.