CHAPTER 2

“A Gilded, but Gritty Age”

For in gay New York where the gay Bohemians dwell, there’s a Colony called the Tenderloin, though why I cannot tell. A certain man controls the place with no regard for coin—the Czar, the Czar, the Czar of the Tenderloin.

—BOB COLE AND BILLY JOHNSON, “THE CZAR OF THE TENDERLOIN, ” 1897

James Henry Williams was born on August 4, 1878, a Sunday, at 227 West Fifteenth Street. His mother Lucy gave birth in perhaps the very same bed in which she had birthed two sons before him and would birth another son and a daughter after him. It was a building filled with working poor tenants in varied occupations: waiters (his father), laundresses (his mother), carpet cleaners, a music teacher, servants, and housekeepers. The presence of a calciminer evokes a city still amply built of wood for some to whitewash for a living. About nine families lived in the building, which included a separate apartment in the rear. Although the building was black throughout, the adjacent house on the right was mixed with black and white tenants, as was its block between Seventh and Eighth avenues.1

Though the specifics of young James’s childhood are uncharted, a prominent church, a school, and various businesses nearby attest to his being born into a considerably established black community. At barely two years old, he was too young to recall a controversial incident (but surely grew up amid its retelling) that shook the antebellum Union AME Church, a block east on Fifteenth Street: one of the most sensational murder trials of the Gilded Age. The widely covered case involved a black porter, Chastine Cox, who was sentenced to hang for killing a white socialite, Jane De Forest Hull, during a burglary. “If there was ever a cold blooded murder or a man who richly deserved to be hung, Cox is that man,” Frederick Douglass, by then a U.S. marshal, said, urging that the fullest legal penalty be meted out promptly.2 But while the course of Cox’s murder trial patently engaged race and class, it also interwove fraught issues of medical jurisprudence (involving suspended animation and phrenology), cultural solidarity, and even celebrity sympathy (some called him “the handsome criminal”). Ashton’s waxworks exhibit, near City Hall, added to its life-size figures of Napoleon, Queen Victoria, Pope Pius IX, and Washington Crossing the Delaware, a figure of “Chastine Cox, murderer of Mrs. Hull.”3 On July 16, 1880, Cox was hanged in the Tombs. Until the night before, reports had held that his body would be taken to the Union AME, where the Rev. James Cook had promised Cox a church funeral. But congregants and neighbors descended on the church—perhaps little James among them, clutched in his mother’s arms—and “condemned the project in unmeasured language.”4

James, and likely his two older brothers, John and Charles, attended the venerable Grammar School no. 81, at 128 West Seventeenth Street—called until recently Colored School no. 4. The three-story brick building had numbered in a series of racially segregated schools that, despite the unkind cause of its inception, had become a source of pride for generations of black New Yorkers. The schools were begot from the first African Free School that had been established on Mulberry Street in 1787 by the New York Manumission Society (whose prominent members included Alexander Hamilton and John Jay) to educate Negro children in preparation for the abolition of racial slavery in the state—which ostensibly came about on July 4, 1827. The society’s longtime president Cadwallader D. Colden—a former abolitionist mayor of New York, though namesake to a prominent slaveholding grandfather5—founded seven African schools before he died in 1834. A number of their thousands of alumni were prominent members of young James’s community and integral to shaping his world. The iconic representation of African Free School no. 2 was a student drawing by master engraver Patrick H. Reason, whose brother Charles L. Reason was principal of Colored School no. 3, on West 41st Street—where Elizabeth Jennings (now Graham) was a longtime teacher—which became Grammar School no. 80, on West 42nd Street. The Williams’s next-door neighbor was Richard Robinson—who had succeeded William Appo, one of the country’s most renowned black musicians—music teacher for both Colored Schools no. 3 and 4 and a former pupil at the latter. In the mid-1880s, James entered a singular African-turned-Coloredturned-Grammar-School system with long, intimate connections and proprietary sentiments.

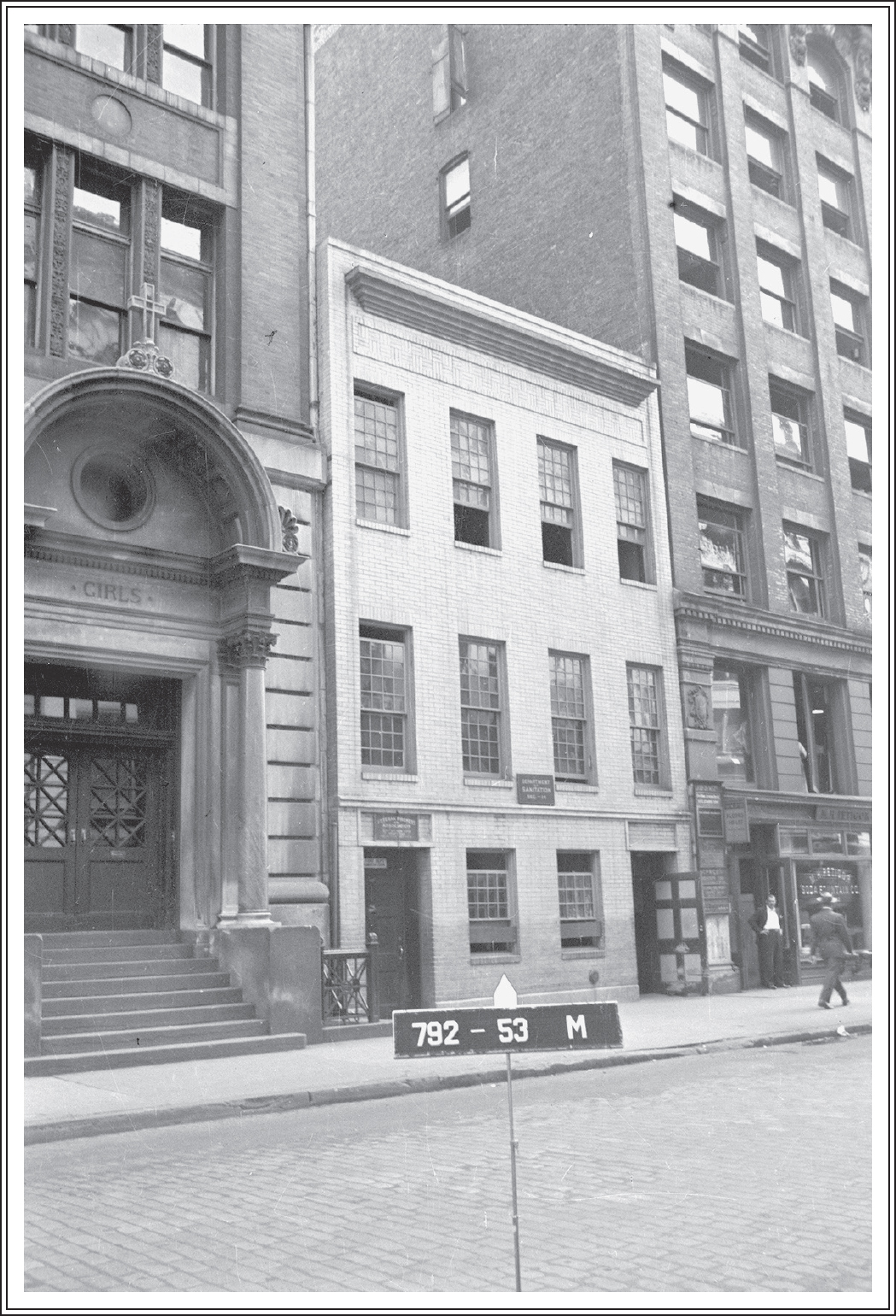

Established decades earlier in Harlem before moving around 1871 to 128 West 17th Street, Colored School no. 4 was born of the city’s late-eighteenth century African Free School movement. New York Municipal Archives.

Another esteemed teacher, Joan Imogen Howard, from Massachusetts, had also brought her considerable musical experience to New York’s Colored School no. 4. Howard had been noticed by James Monroe Trotter, the country’s first black music historian (and father of civil rights activist and newspaper founder William Monroe Trotter). “When in Boston this lady exhibited commendable zeal in the study of music, and at an early age was quite noticeable for good piano-forte performance,” the senior Trotter wrote.

Trotter also noted the unfolding career of one of Howard’s critically promising young graduates, Walter F. Craig, who “will ere long be ranked with the first violinists of the day. He has lately composed a march.”6 The debut of Craig’s march, “Rays of Hope,” coincided with Williams’s infancy. Over his career, the composer would produce such notable works as “Selika’s Galop,” which he dedicated to his onetime partner, the coloratura soprano Marie “Madame Selika” Williams—hailed as “the queen of the staccato”—who on November 18, 1878, was the first black artist to sing at the White House, at the invitation of President and Mrs. Rutherford B. Hayes. James Williams likely knew Craig his entire life, for the maestro and the Williamses’ neighbor Robinson had been classmates at the Seventeenth Street school. As James grew up, any program featuring Craig—who was said to be the first black allowed to join the all-white Musical Mutual Protective Union—signaled that entertainment’s high social magnitude,7 for black and white audiences alike. Unquestionably, “W. F. Craig’s Famous Orchestra,” as it was often billed, was a central musical backdrop to James’s boyhood. And he came of age under the same watch as the maestro’s: Sarah J. Tompkins Garnet, who was the first black principal in the city’s public school system.8

Teacher Joan Imogen Howard, of Colored School no. 4, became the only black manager at the Chicago’s World Columbian Exposition of 1893. Women of Distinction: Remarkable in Works and Invincible in Character, L.A. Scruggs. Raleigh, 1893. Internet Archive.

In 1863 noted educator and suffragist Sarah J. Tompkins Garnet, of Colored School no. 4, became the first black principal in the New York City (then just Manhattan) public school system. NYPL Digital Collections.

But the continued existence of the colored schools was in question, a consequence of the state’s 1873 civil rights bill ensuring that black children could attend any public school. Despite its century-long lineage, no. 4 had already suffered evident attrition by the year James was born, when the board of education began agitating to disestablish all the separate caste schools. During Grover Cleveland’s two years as governor of New York, 1883–85, a movement arose in the state legislature to absorb the city’s colored schools into the general ward school system. The initiative fueled concerns that the new organizational schemes would disenfranchise black teachers.

So on February 12, 1883—Lincoln’s birthday—throngs of black New Yorkers descended on Chickering Hall, at Fifth Avenue and Eighteenth Street, a popular social hall where the colored schools frequently held commencement exercises. A letter of support from Frederick Douglass galvanized an action committee (which included Peter Porter) to confront the board of education: either give black teachers parity with their white counterparts, or leave the colored schools as they were.9 Their argument proved effectual and appeared to turn the tide in their favor: the following year at Chickering Hall, about 150 boys and girls, all dressed in white, for Grammar School no. 81’s commencement ceremony, cheered as a former graduate praised the governor for refusing to close the colored schools.10 A few months earlier, Cleveland had signed a legislative bill that allowed Colored Schools no. 3 and 4 to continue independently (as Grammar Schools no. 80 and 81) of the predominantly white schools. “I know that whatever I did was in favor of maintaining separate colored schools instead of having them mixed,” Cleveland later recalled.11

Even after Cleveland’s action, the colored schools had to struggle to retain some of their racial singularity for a few more years. At Grammar School no. 81, principal Sarah J. Tompkins Garnet was the widow of the former U.S. minister to Liberia, Rev. Henry Highland Garnet, who was himself an African Free School graduate. In March 1887, Principal Garnet chaperoned a number of her pupils to a celebration of the Fifteenth Amendment at Bethel AME Church in Greenwich Village. The children, who perhaps included eight-year-old James, “illustrated the four epochs in the history of the American negro—slavery, freedom, citizenship, and suffrage.”12 But by the next year, Principal Garnet saw attendance drop as the community shifted. Black children were increasingly going to predominantly white schools, like the Williamses, who five years earlier had moved from West Fifteenth Street to West 33rd Street. “This was formerly known as an exclusively colored school and our pupils came from all parts of the city,” Garnet said, “but now they have left in order to attend schools nearer their homes.”13

More than just new school access, many pupils were also finding new job opportunities. At a time when child labor was more liberally practiced, it was conceivable that James’s schooling began to instill in him a work ethic at the threshold of adolescence. And perhaps James got a little push from his father. It’s easy to imagine John Wesley Williams dashing out of Sturtevant House in his waiter’s apron and making a beeline to the fancy flower shop at Coleman House, just across Broadway, and unrolling the newspaper for the proprietor to confirm the advertisement’s message. One can imagine him boasting that he had two good boys, three if needed: John Jr. and Charles were twelve and eleven; and James was nine. For in the hard era that they lived in, the boys had come of age to at least be trade apprentices, if not breadwinners. Thorley’s Roses would be as good a place as any to start.

On December 4, 1887, Charles Thorley, renowned as the florist of New York’s aristocracy, had advertised in the Herald for “two boys as messengers; must live with parents.”14 Whether he was looking to hire two colored boys specifically is not known—nor whether James started working for him that year—but it is known that Thorley’s shops became familiar for decades for their almost exclusively colored staff, which at some point included James as a florist messenger.

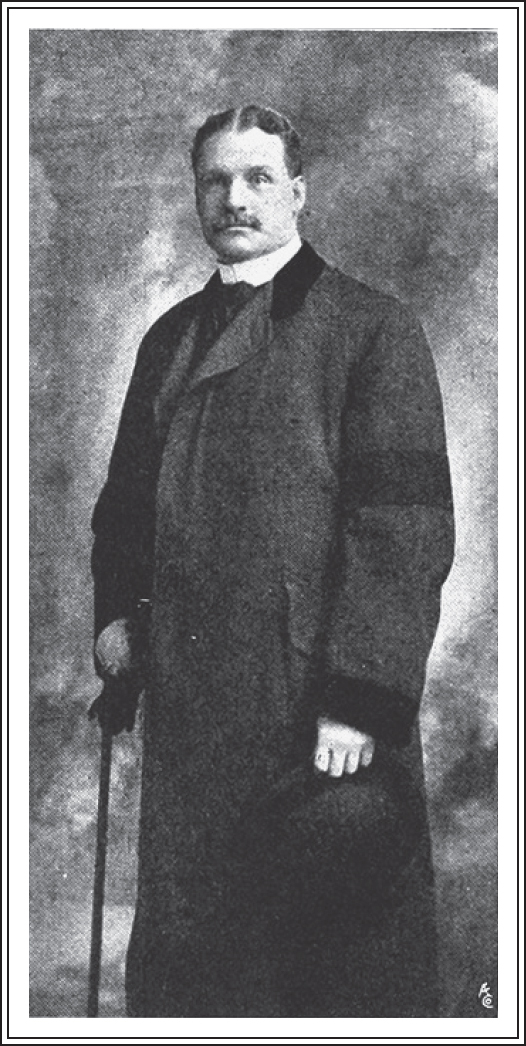

At six feet tall, Charles F. Thorley looked imposing within his element: handling delicate, vividly colored flowers. A soft helmet of auburn hair topped his round face, which balanced a faint mole on the right side of his upper lip. Born in New York City in 1858, Thorley had followed his English-born father in the flower trade, in which he proved himself a prodigy: an 1872 city directory listed the teenager as a florist on West Street. By 1883, the twenty-four-year-old had been running two successful greenhouse businesses around Fifth Avenue’s posh Ladies’ Mile shopping district, where he regularly provided free bouquets for women patrons of Tony Pastor’s (called the “Father of Vaudeville”) Fourteenth Street Theatre.15 But on February 2, ruined by a financial recession, he auctioned all his stock-in-trade of plants, wire frames, baskets, counters, piping, and the boiler to pay off creditors.16 Soon afterward, as a story had it, Thorley was walking dejectedly up Broadway until he reached Coleman House, between 27th and 28th streets: he stopped to ponder a sign advertising the little vacant storefront for rent, but not feeling even a dollar’s worth of coins in his pocket, he continued on.

However, Thorley returned the next morning. The sign in the store still directed him to inquire at the hotel a block away, the famous Gilsey House. Looming like a picturesque white château above the northeast corner of Broadway and 29th Street (across from Sturtevant House, where James’s father worked), the Gilsey’s five-story cast-iron pile was topped by an additional three-story mansard roof. The elegant hotel was the irresistible focal point of the hotel and theater district. It was where the English writer Oscar Wilde had stayed the year before, when beginning his American lecture tour at Chickering Hall.

On this day, Thorley found himself face to face with old Peter Gilsey, Jr. (whose late father had also built Coleman House), who asked for $2,500 a year, three months in advance, for the storefront’s rental. Though Thorley feigned indifference as he heard out the terms, his fingers worried a gem in his pocket, which he hastened to pawn as soon as he left. He returned and managed to talk Gilsey into accepting fifty dollars for one month’s rent. Upon his success, Thorley went back to the store and noticed a secondhand lumberyard nearby, as well as a place to buy two chairs, a counter, a mirror, and a chandelier. He repapered the walls. When the place looked once again like a shop, he stocked it with flowers. He stepped outside his new store, and spying old Gilsey approaching—no doubt to look in on his new tenant—he turned out the last few coins from his pocket and toyed with them for Gilsey’s benefit. Then he suddenly tossed them clear across the street to the roof of an old boardinghouse. “That’s the last sixty cents I have,” Thorley confessed to his baffled new landlord. “If I haven’t got more than that by to-morrow night you are going to have a bad tenant.”17

Charles F. Thorley, one of the most influential florists of Gilded Age Gotham, notably employed black staff. American Florist, Internet Archive.

By the mid-1890s, Thorley’s Broadway flower shop under Coleman House thrust young Williams at the intersection of Broadway shoppers, Tin Pan Alley music makers, and idling tourists. MCNY.

Gilsey had no reason to worry. In the early 1890s, working poor families of the Tenderloin like the Williamses saw businesses like Gilsey House and Thorley’s Roses defining the posh fringe of their district. Charles Thorley was largely credited with promoting the orchid to its viability as a market flower. The bloom usually appeared only occasionally at some opulent event, but suddenly it thrived exponentially among his fashionable clients. Due to Thorley’s penchant, “at least five hundred Orchid-flowers are sold to-day,” it was claimed, “where one was sold half a dozen years ago.”18 Gilded Age versifiers frequently dedicated couplets to his blooms or services: a “liv’ried messenger / With cocky, flippant air—gamin depraved—/ Brings Thorley’s roses at two ‘plunks’ the head.”19 But the florist’s high reputation suggests some poetic license was taken in the unflattering allusion to the delivery boy, who by this time might well have been a fourteen-year-old teenager like James Williams.

In a fictional family portrayal a century later, a Williams descendant would invoke Thorley’s flower shop as the setting of James and his sweetheart Lucy’s first meeting. The apt conjecture is not surprising. More than most retail stores, Thorley’s had the theatrical magic to stir romantic sentiments, and it was indeed the likeliest place for the youngsters to court. Even before entering, customers often paused in stupefied admiration at the florist’s delivery wagon at the curb, “resplendent in gold trimmings and uniformed driver.”

Thorley’s shop quickly became a dazzling feature among Broadway florist and dry goods merchants: the “oriental magnificence” of colorful delivery wagons belonging to various firms.20 It is easy to imagine Lucy Metrash stepping inside Thorley’s—sometime in 1895, when she was about twelve or thirteen—chaperoned by her grown-up sisters Caroline and Mamie (who were nineteen and eleven years older, respectively), and losing herself instantly in the ecstatic decor. The ceiling was barely visible, covered by a canopy of orchids and other flowers and greenery. Thorley’s undulating maidenhair ferns were “finer than all the feathers on all the fine birds unshot,” Mary Bacon Ford wrote, offering a weirdly telling allusion to the millinery fashion of the time.21 Thorley’s was the likeliest place for Jimmy and Lucy to court. Lucy would have shopped as James worked (or each at least pretended to), he asking if they (but caring only if she) had ever smelled this or that blossom, and Lucy coming up with more questions for the genial attendant.

Though Williams and Lucy’s affections were mutual and deepening, the two were hardly from the same social worlds. Racial mores and prejudices were levelers. Both of Williams’s parents were former slaves from Virginia and had to work hard—his father as a hotel waiter, his mother as a laundress—to keep the family in good financial condition.

But Lucy’s parents were northerners, descended from generations of free blacks. Though her father’s side was from Connecticut, she had old New York connections. Indeed, a traffic accident had put her grandfather’s name in the papers some fifty years before, a time when reckless coachmen were “almost universally in the habit of racing furiously through their routes.”22 It was on one of the spectacular Broadway coaches owned by Francis A. Palmer, president of Broadway Bank. In spring of 1844, Eaton, Guilbert & Company, a renowned coach manufacturer in Troy, New York, made fifteen new coaches for Palmer’s fleet of public omnibuses. One paper described the horse-drawn carriages—uniformly painted with scenic panoramas of City Hall Park and its environing mayoral manse, sparkling fountain, St. Paul’s Episcopal Chapel, and adjacent buildings—as “far more elegant than any omnibuses now running in the streets of New York.”23

But on July 3, a driver crashed one of Palmer’s new conveyances into a lamppost. The impact threw Adam Metrash, “a respectable colored man”—and the grandfather of James Williams’s budding sweetheart Lucy—from his Jim Crow seat beside the coachman. Few New Yorkers were surprised: just two months before, another of Palmer’s stages had crushed a three-year-old Irish girl.24 The constantly ignored demands to protect the public against heedless coachmen now fueled anger over the Metrash case. One outraged citizen wrote to the Commercial Advertiser of this “flagrant case of inhuman misconduct.” Not only had the crash thrown Metrash from the carriage, the driver had abandoned his injured passenger on the pavement. Metrash had to make his own way home, an arm “broken just above the wrist and one of his legs much bruised.” The irate writer insisted that a mayoral inquiry start with the omnibus owner Palmer himself.25

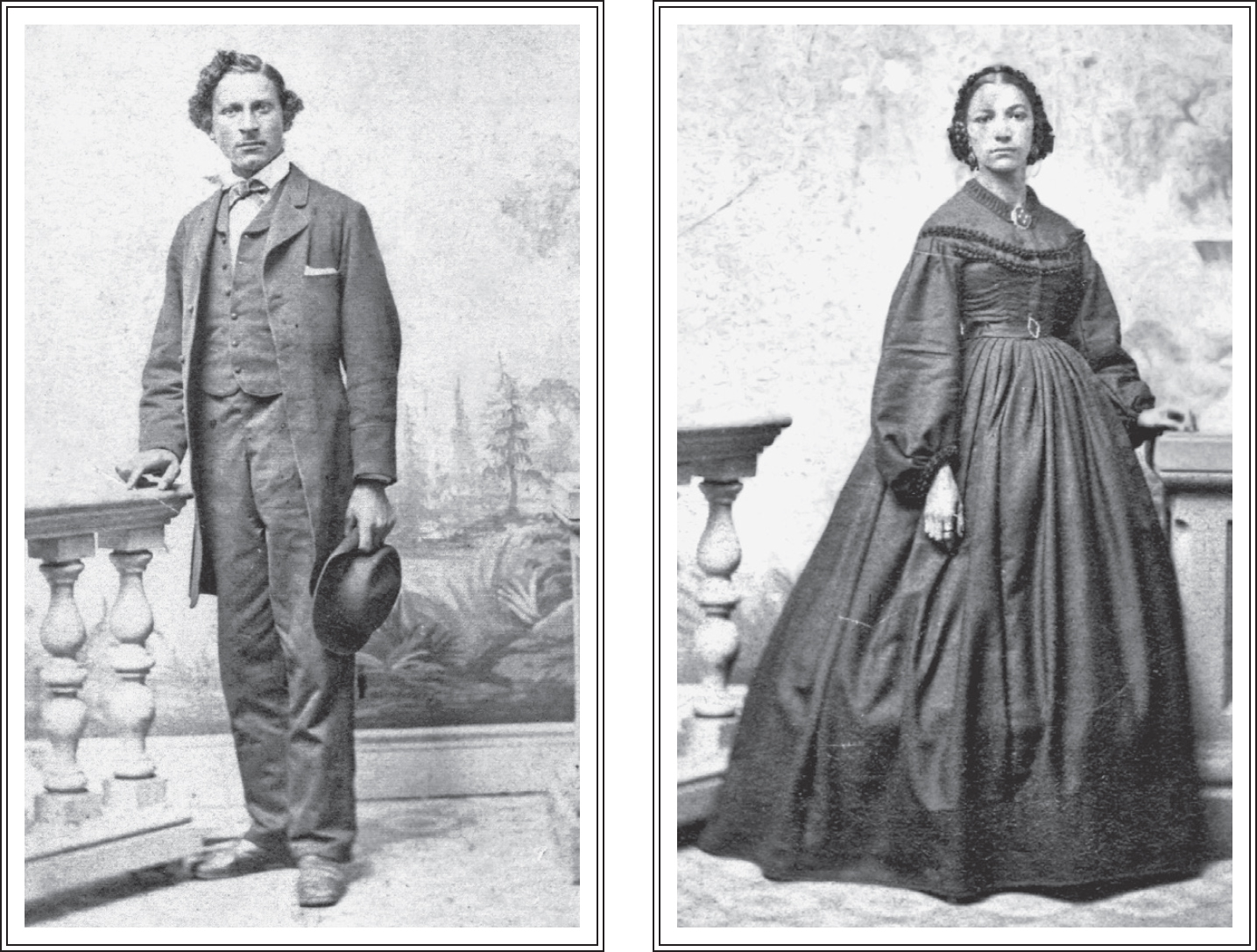

This episode happened before Williams’s time, but he was raptly interested in any utterance from this young lady, Lucy Metrash, from Connecticut. Her father, Adam Metrash, Jr., was a boatman and oysterer, whose family “had made their home in the coastal town of Norwalk since the 1790s.” Her mother was from New Jersey. Their paths had crossed by way of a singular social circle within and without the Negro community: both her parents were deaf. According to record, a cannon discharge had deafened her father Adam Jr., born in 1837, when he was only one and a half years old. Her mother, Elizabeth Pepinger, born in 1838, was four when a bout of scarlet fever left her deaf. If accident and illness had caused both of her parents’ losses of hearing, it appeared to be an ill-fated coincidence that her eldest sibling Robert was also born deaf.26 The sight of Lucy’s family signing fluently introduced a world perhaps unfamiliar to Williams.27

In 1852 fourteen-year-old Elizabeth Pepinger attended school in New York. In 1858 she was in the first graduating class at Fanwood, the New York Institution for the Deaf’s new building facility in Washington Heights. The principal awarded her a premium for her obvious artistic talent: a drawing book, two lead pencils, and a rubber eraser.28 Pupils in the deaf community—who often knew disparagement both at home and in society—had a certain advantage over hearing pupils: unlike students at the city’s segregated public schools, black and white classmates of antebellum schools for the deaf commingled in scholastic learning as well as recreational and ceremonial activities and general deaf community events. Still, some black applicants surely erred on the side of caution. Elizabeth’s inconsistent racial descriptions suggested to one historian that “she may have been passing for white at school.”29

Descended from generations of free blacks, the late parents of Williams’s wife, Adam H. Metrash and Elizabeth Pepinger (circa 1860s) of Norwalk, Connecticut, were prominent in black deaf society. Charles Ford Williams Family Collection.

Whatever the school’s progressive stance on integrating, inevitable events highlighted the prevailing prejudice. During Elizabeth’s tenure at Fanwood, twelve-year-old Charles Wia Hoffman came to the school from Cape Palmas, Liberia. Three decades earlier, in 1822, the American Colonization Society had established Liberia to “repatriate” formerly enslaved African Americans. Cape Palmas—annexed to Liberia in 1849—became a prominent outpost presided over by the Rev. C. Colden Hoffman, a New York Protestant Episcopal missionary. Charles was eventually brought to the New York Institution for the Deaf, probably by Hoffman himself. Unfortunately, in 1858, only a few months after he arrived, the boy died of tuberculosis. His body was interred a few blocks away in Trinity Church Cemetery, where Fanwood maintained the institution’s communal plot. But irrespective of the racial integration within the asylum’s walls, the cemetery’s rules sadly obliged that the boy be buried in its segregated “colored ground.”

Where and how Lucy’s father met her mother is unknown. Adam Metrash, Jr., was an 1857 graduate of the preeminent American School for the Deaf at Hartford, founded by Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet. He and Elizabeth were wed in 1861, but their marriage record did not specify a date or place. Though they belonged to St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Norwalk, whose churchyard still retains many of their family members, the couple very likely wed at St. Ann’s Episcopal Church for Deaf-Mutes in New York. Founded in 1852 by Gallaudet Jr., the church on Eighteenth Street and Fifth Avenue was the best known in the deaf community. Of Lucy’s three older siblings—Robert, born in 1864; Mary (called Mamie), born in 1869; and Caroline, born in 1872—at least two, plus their adult father, had been baptized at St. Ann’s.

The church document listed only three of the Metrash children: Robert, deaf, born in 1864; Mary, hearing, born in 1869; and Caroline, hearing, born in 1872. Lucy was born a year after the census, on October 8, 1881. Already entering middle age, their father Adam got himself baptized at St. Ann’s in 1874, and ten years later, on July 21, 1884, he died at forty-seven. In 1887 Robert married—he and his wife, Anna, had a baby girl named Grace the following year—and worked as a boot and shoe maker in Bridgeport. But in the late summer of 1893, six years after his marriage, he was reportedly living alone in Stamford when he died at twenty-nine. Just months after her brother’s death, twelve-year-old Lucy’s widowed mother Elizabeth died, too, on February 5, 1894. Probably not long afterward her big sisters Caroline and Mamie put things in order and fetched her to move down to New York City.

Mary (“Mamie”) Metrash, one of Lucy’s two older sisters, probably in the 1890s. Charles Ford Williams Family Collection.

With Connecticut behind them, the Metrash sisters had good reason to frequent Thorley’s, apart from the enchanting floral displays: his stores were conspicuously staffed by Negroes. The owner was well known among blacks as a friend. At Thorley’s Roses on Broadway and at the subsequent House of Flowers on Fifth Avenue, the florist’s able staff of liveried messengers, a chauffeur, a valet, shop clerks, and a purchasing agent were by and large race men. This fact no doubt made Thorley’s retail shops a nexus for refined colored society folk to communicate matters both urgent and trivial that contributed to racial uplift. What conversations caught fire in Thorley’s that mid-week day of February 20, 1895, when the sorrowful news spread across the nation that Frederick Douglass had died? Lucy, at thirteen, might have asked sixteen-year-old James what he thought about it. The two teenagers would have discussed family matters, like James’s newborn baby brother, Richard Alexander, as well as more political issues like the Malby Bill, yet another new civil rights law that meant they had the right to stay in the same hotels, eat in the same restaurants, and buy the same theater seats as whites.

Did Williams tell Lucy and her sisters the pie-girl story? Though the shop clerks were not invited guests, they were privy to details of a sensational party that spring that culminated in a gossamer-clad artist’s model leaping from the crust of a giant pie. About a dozen Negroes had been essential to the festive ambiance: “To insure ample entertainment, four banjo players were employed and the same number of colored jubilee singers were engaged. . . . Thorley provided the flowers.”30

It could very well have been over such news or gossip that, if her guardian sisters were not paying attention, James and Lucy first touched hands.

In 1895 railroad passengers arriving in New York learned that a new amenity awaited them at the Grand Central Depot, unlike anything they recalled in the station’s quarter-century history. By the War of 1812, the teenage Cornelius Vanderbilt had already shown enough promise in the harbor trade to be nicknamed “Commodore,” as the shipping magnate was still known during the Civil War, when he sold his last vessels to focus on railroads. He bought and consolidated several of New York’s steam locomotive lines and laid plans for a new terminal on East 42nd Street—sinking Fourth Avenue northward into the track bed that became first a tunnel, then Park Avenue. It opened in 1871 as Grand Central Depot. Later in 1898 the depot was rebuilt as Grand Central Station, and again in 1913 as Grand Central Terminal. Observers remarked that certain traveling disadvantages in the station’s earlier years had not much improved for women or strangers who arrived in New York City by train. Women risked “falling into the hands of bunco men or worse,”31 and foreigners unable to speak English were at the mercy of those who did. The situation was endemic to transit terminuses.

But on March 1, 1895, passengers arriving at Grand Central Depot on the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad found leaflets in the cars informing them that station attendants would be waiting to assist them in various ways. These new attendants would be easy to recognize by their blue uniforms trimmed with bright red, and by their red caps. Their distinctive uniforms were meant to make them unmistakable from others worn in the station or from casual street garments, and therefore easy for a passenger to recognize. “One of these men will be found at the end of every car on the arrival of all trains,”32 the railroad’s general passenger agent George H. Daniels explained. He’d hired a trial staff of twelve men, preferring men over boys to instill a greater sense of professionalism. Daniels was widely known for his constant efforts to perfect passenger comfort on the New York Central’s “Great Four-Track Line,” and it was a rare periodical that didn’t describe or advertise the railroad’s new feature of “twelve uniformed men to be known as attendants”33 put on duty at the Grand Central Station.

The new free service was a wonderfully practical idea from the point of view of the general traveler, especially those in the rear cars of long trains who had to walk some five hundred feet to the street exit. The attendants’ explicit duties were “to help women with their hand-baggage, to lead a child if necessary, or to assist a feeble person.”34 And mindful of New York’s nonnative visitors—often bewildered strangers—Daniels noted that “the foreigner will be as readily served as the American,”35 as he installed a polyglot force that included speakers of French, German, Spanish, Italian, Danish, and other languages in addition to English.

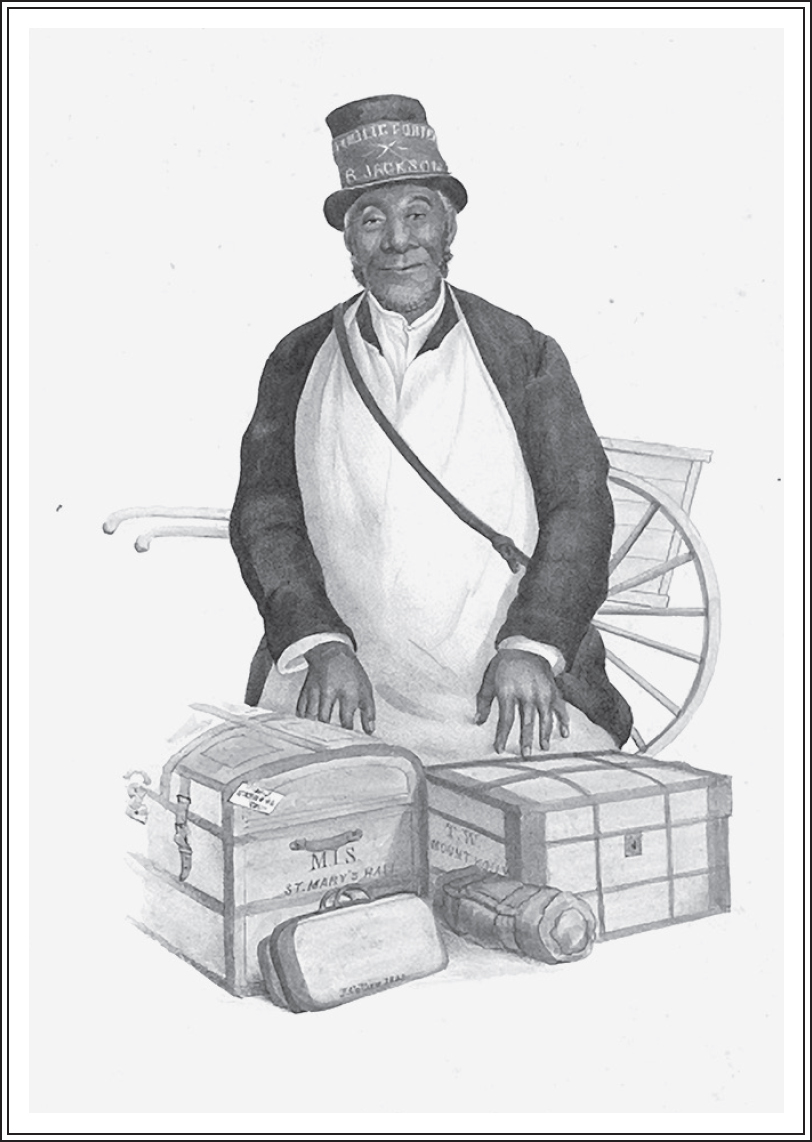

An 1883 depiction of a black public porter in a vivid red-sashed hat suggests a precursor to Daniels’s red-cap system, and to its origin with Williams. Library of Congress.

Despite general public enthusiasm, some of Daniels’s railroad industry colleagues were perplexed as to why his new uniformed attendants should be classified separately “from the ordinary porters at the station, who attend both outward and inward passengers.”36 But Daniels intended them to be out of the ordinary. More chaperones than lugs, the men would direct passengers to the right streetcars, or flag them cabs. Though they would carry hand-baggage, they would not handle heavy baggage—as Daniels emphasized, “They are not porters.”37

Daniels’s directive was probably naive. One couldn’t please everyone. A woman having “alighted from incoming trains fully six times this summer, laden with flowers, packages, valise, &c.,” was incensed that “the red headed men” at Grand Central just “stood idly by.”38 Her injured vanity aside, one might appreciate the woman’s mortification as she realized her alternatives. There were the city’s licensed “public porters,” who, black and white, were impudent and boorish. Or there were the half-dozen or so street urchins who likely clustered around her, worrying at the handles of her handbags. These “baggage smashers,” as everyone knew them, were a familiar sight at railway stations—Grand Central, the Cortland Street Station of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and the Barclay and Christopher Street stations of the Lackawanna Railroad—and at riverfront ferryboat landings.39 Such hustling opportunities were where many boys first honed their entrepreneurial skills and tested their powers of charm. They were mostly adolescent boys, around the age of Williams, who was about seventeen, though a fair number of man-sized fellows sometimes stood out as well. A stranded lady commuter could not avoid hearing their full motley chorus: “Smash your baggage, miss?” The age-old greeting was as familiar as a folk ballad.

Despite a few misfires, Daniels’s experiment proved a clear success within a year. He had simply piped the company’s standard blue garments with red trim and topped the ensemble with a red cap. By fashioning the free-attendant service as a distinct unit of the railroad’s workforce, he had also codified the ancient practice of livery—special uniforms worn by servants or officials. This dress code redefined and promoted the impression of the entire corps of uniformed help as an essential component of a great railway station. Daniels quickly built up the attendant system at Grand Central, where travelers soon encountered neat and tidy redcapped men throughout the station. Red Caps greeted them at entrances to waiting rooms, ready to assist them from carriages and escort them to trains, and they stood on all the arriving train platforms. Articles and advertisements reiterated that the service was “absolutely free,” that “no tips are necessary,” and that the attendants were “active and intelligent, polite and well posted; they speak several languages and are walking encyclopedias.”40

New York Central Railroad’s general passenger agent, George H. Daniels, generated the most company publicity, such as an 1896 ad for its new “Red Cap” service. Author’s collection.

Beyond New York City, the traveling public was soon enjoying Daniels’s “free-attendant service” at Buffalo and Albany and in other large stations of the sprawling network. The system subsequently spread even farther away, to the Northwestern Line’s Chicago station, to the Pennsylvania’s Jersey City station, and to numerous other railroad stations nationwide. Within a few years, a traveler would have been able to identify the free amenity anywhere by the presence of a red cap.

To be sure, the railroad companies’ uniformed employee system reflected an increasingly discrete, military-like regimentation of dress standards for laborers. Just two months after Daniels installed his Red Caps, the city’s street cleaning superintendent, Col. George E. Waring, inducted his iconic army of White Wings, clad in white duck-cloth uniforms and helmets. Not all workforces liked the idea; while City Hospital physicians agreed to wear white duck coats on duty, nursery maids objected to wearing “a livery” ensemble of caps and aprons. But by and large, the art of discipline appeared to induce other managers of labor to court public trust with work teams whose attire exemplified tidiness: clean clothes, polished shoes, bright buttons, and shaven faces combined to imply trustworthy authority. The trend in heightening, or tightening, dress standards was visible among doormen, hallboys, elevator operators, and messengers in first-class hotels and apartment houses.41

It was in this decade that young James Williams moved in the ranks of varied uniformed service, although he may also have picked up some plain-clothed baggage smashing on the streets for extra money. The nimble teenager’s various hats included the pillbox and elastic chin strap of a hotel bellhop, which he also wore while on duty as a florist messenger at Thorley’s.

In January 1897, two years after he met Lucy, Williams was still living with his parents at 454 Seventh Avenue, just above 34th Street, across from where Macy’s department store would eventually dominate for generations. The area was infamously known as the Tenderloin, an epically sordid entertainment and red-light district. The sector stretched amorphously up Manhattan’s West Side from about 24th Street to 62nd Street, between Fifth and Ninth avenues—including a foreboding swatch of blocks around 39th Street known as Hell’s Kitchen. The zone abounded with so-called “disorderly houses,” gambling dens, saloons, and pool halls that were the constant target of antivice crusades, police shakedowns, and exchanges of graft. Indeed, its colorful nickname was attributed to “Clubber” Williams, a fearsome police captain transferred there in 1876, who savored the prospective bribes that would advance him from his usual chuck steak to “tenderloin.”42

Yet a newspaper’s map illustrating the “proximity of evil to schools and churches” revealed pulses of respectability dispersed throughout the area as well.43 The joyful noises around the intersection where the Williamses lived—if raucous even by the Tenderloin’s peculiar standard—were often more sacred than profane: some local residents had recently complained to the board of health that “two rival negro congregations” kept them up nights, worshipping too vociferously in an avenue meeting hall.44 James and Lucy were restless for other reasons: they were about to get married.

Lucy was living about ten minutes away from James, at 321 West 41st Street, possibly with one or both of her elder sisters. On January 31 the teenagers met each other at the northwest corner of Seventh Avenue and 39th Street, the path to Hell’s Kitchen, where they entered St. Chrysostom’s Episcopal Chapel. In 1883 the church’s black members had formed the Guild of St. Cyprian (an African saint and a usual indicator of black congregants), a mutual benefit society that, like a fraternal order, collected a membership initiation and monthly dues “for colored men and women, providing for its sick, and burying its dead.”45 Yet the formality of their wedding at this particular church, to which neither belonged, had the ring of elopement to it.

Despite its sacred authority, this church had a dubious history with marriages. A few years earlier, St. Chrysostom’s Chapel was “apparently much sought after by runaway couples and others desirous of entering the matrimonial state as expeditiously as possible.”46 The church’s marriage certificate did not request birth dates, and watching the Rev. Thomas Sill fill in their answers to his questions in his own hand, James and Lucy gave only their ages. “Twenty years,” the bridegroom replied confidently. “Eighteen,” his bride diffidently murmured. The vicar recorded their ages, but truth be told, James and Lucy were eighteen and sixteen, respectively, two years younger than they claimed. No matter the age of consent, the teenagers had good reason to want to appear older on record, or at least more mature: Lucy was pregnant. Less than eight months later, James moved to Lucy’s address where, on August 26, 1897, she gave birth to their first child: Wesley Augustus Williams. The baby’s birth certificate incidentally listed James as nineteen, which he had turned earlier that month, and Lucy as seventeen, which she would become in October—making them younger than on their marriage certificate.47 Within a year, they moved directly across the street to 318 West 41st Street, where on August 22, 1898, their second child, Gertrude Elizabeth Williams, was born. Their father’s occupation as a hotel bellhop, as the birth certificates of both children indicated, attests to Williams’s vigorous work ethic if he determined to eke out a living beyond the flower shop.