CHAPTER 3

“If We Cannot Go Forward, Let Us Mark Time”

We ask for no money consideration—the rights of citizenship we value above money.

—W. H. BROOKS, 1900

By the summer of 1900, Williams had moved Lucy, Wesley, and Gertrude out of 318 West 41st Street down to 228 West 28th Street, which at the time was still considered “uptown.” The surrounding neighborhood, still part of the Tenderloin, had supplanted the old black belt around Sullivan and Thompson streets, where his father first landed from Virginia a quarter of a century earlier. Greenwich Village’s black population had now thinned out, with residents moving even well beyond the closer tenement blocks to the suburbs of Brooklyn, and to the Bronx sections of Williamsbridge and Kingsbridge. Zion AME Church was still on Bleecker Street, and the Abyssinian Baptist Church was still on Waverly Place and Grove Street, but other black churches were already dotting the map uptown from 25th Street to 163rd Street.1

Migratory and professional progress appeared to go hand in hand. Whereas for years the public had patly assumed black men, by dint of race alone, to be barbers, hostlers, coachmen, and waiters, they were now entering “many of the most respectable callings” of doctor, dentist, and entrepreneur. One white writer observed that blacks were at the helm of at least two full all-Negro theatrical companies—Williams & Walker and Cole & Johnson were leading black performance teams—but black New Yorkers knew there were others. A Negro owned a prosperous Seventh Avenue cigar store, and on Sixth Avenue a colored man was the instructor of a school of podiatry and manicure that was “attended only by white pupils.”2

Even if Williams did not own his own business, such observations no doubt fueled his enterprising nature. Though he had not yet moved his young family out of the Tenderloin, his walks to work barely three blocks east were now infinitely more convenient. That year’s census gave his occupation as a florist messenger, but his actual duties at fashionable Thorley’s Roses at 1173 Broadway belied that lackluster title. Williams’s “messenger” duties often required diplomatic finesse and intuition, sometimes even a hint of corporate sleuthing. His boss was the flower merchant of choice for the “Four Hundred” of New York’s exclusive Gilded Age society. His association with Thorley’s modish shop was auspicious inasmuch as it seasoned him, like an apprenticeship, in the art of service with discriminating taste and tact.

Charles Thorley’s creative genius stimulated the practice of giving particular cut flowers for particular occasions—roses, orchids, violets—and presenting them in ceremoniously wrapped paper and boxes. Citywide, nationwide, and even thousands of miles away in Europe, the trends of romantic aspiration, consummation, breakup, and patch-up were traceable through flower orders in Thorley’s business ledgers. His enterprise eventually became the three-story mansard-roofed House of Flowers—its exterior walls cascaded florid tendrils from every window—at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 46th Street. It was reputedly the largest cut-flower business ever built in the country. Williams likely also witnessed the event for which his boss acquired his most recent fame. Thorley owned a lot at the corner of Broadway and 42nd Street, and he now leased it for $8,000 to The New York Times, whose later skyscraper would mark that intersection—then known as Longacre Square—as Times Square, the crossroads of the world. Years later, when Thorley died, many black New Yorkers would mourn the loss of a sincere friend, whose Negro employees in executive positions “practically managed his business for a number of years.”3 His carriage driver was Henry Crum, an unassuming former South Carolinian whose brother, Dr. William D. Crum, was one of the most prominent Negroes of that state. In 1902 President Theodore Roosevelt would appoint Dr. Crum collector of the Port of Charleston. (Not incidentally, Dr. Crum’s wife Ellen was the daughter of the legendary fugitive slave couple William and Ellen Craft, who stayed a spell at Porter’s Mansion after the Civil War.)

Another place of considerable advantage to Williams was en route to and from work: Jack Nail’s, the most upright colored saloon in the Tenderloin, was at 461 Sixth Avenue, near the southwest corner of his street. Between the predominantly black staff at Thorley’s and the black clientele of Jack’s, Williams was attuned to the constant flow of news pertaining to the race, wherever the geography. That July, for instance, news of American Negroes heading to London for a Pan-African Congress—which summoned worldwide representatives from Great Britain, Africa, both Americas, and the West Indies—surely provoked countless discussions over a few rose thorns here and a few beers there, especially given the current reports of a genocidal campaign in South Africa. D. E. Tobias, an American student organizer and speaker (whom New Yorkers would know better in a few years as the “colored whirlwind”), impressed attendees as he wryly suggested that “the only solution of all the problems lay in according to black men the same justice that white men claimed for themselves.”4 In a few weeks’ time, the claim for justice was deafening in the Tenderloin, as the district became the epicenter of the West Side Riot, the city’s bloodiest campaign of wanton violence since the Civil War.

On August 12, 1900, a white man approached a young black woman standing on a corner at Eighth Avenue and West 41st Street. Robert J. Thorpe was actually a patrolman in plain clothes, and he summarily arrested the woman, May Enoch, for “soliciting.” Enoch protested that she had been waiting for her man in a nearby store, as Thorpe proceeded to usher her to the station. At that point a young black man, Arthur J. Harris, came out of the store and, seeing a white stranger manhandling his girlfriend, rushed to her rescue. In an ensuing scuffle, Thorpe pulled out a billy club to beat Harris. Harris retaliated with a penknife. Thorpe collapsed into a lifeless heap. Then Harris went on the lam.

Williams might have tried to place May Enoch’s face, for the papers said she fled home and gave her address as 241 West 41st Street, just one block east from where he and his family had last lived. In fact, a witness called to Harris’s trial—who testified he saw Harris and Thorpe “holding each other with one hand and striking at each other”5—was a man named Wesley Commodore, who lived at Williams’s old address at 318 West 41st Street.

Thorpe had been a popular officer at the Twentieth Precinct. On August 15, three days after his killing, his body was laid out at his home, where the notorious police chief William S. “Big Bill” Devery, Inspector Walter L. Thompson, and various other officials paid their respects. With Harris still at large, the collective grief devolved into a spirit of vengeance against blacks in general. That day rumors of trouble surged, enough to prompt many blacks to close shops or stay indoors. The rumors proved well founded. That night numerous white gangs known to be “hostile to Negroes and friendly with the unofficial powers that are now potent in police affairs”—that is, Tammany Hall political bosses—ran through the city streets for hours uninhibited, hunting down blacks.6

Under the pretext of restoring order, the police ordered every saloon closed from Twentieth to 42nd Street, between Sixth and Ninth avenues. “Noisy hoodlums” hurled stones at fleeing blacks and drove fists into those they could corner. Cries of “Kill the nigger” filled the night air. Aboard an Eighth Avenue streetcar near 40th Street—around the corner from where the Williamses had recently moved—police rushed to break up several white men punching a black passenger as “two women tried to stab him in the face with hatpins.”7 A mob of fifty men and boys waylaid a 34th Street streetcar and were about to lynch two black passengers from a lamppost with a clothesline when a squad of policemen thwarted them. But apart from a few noted instances of officers keeping the peace, a greater number of them, in compliance with Chief Devery’s orders, clubbed rioters freely to foment the lawlessness.

For weeks following the unrest, newspapers across the country raptly reported accounts of police colluding, by and large, with the vicious gangs. “If the accounts are true, some white men acted last night like beasts,” Magistrate Robert C. Cornell said, censuring the police in the Tenderloin whose own hatred aided and incited abuse of innocent blacks.8 An Ohio newspaper later commended the judge for stopping the police from “dragging Afro-Americans indiscriminately into this court room,” warning that they “ought to arrest more whites to do justice to the riot.”9

One of the victims was Alfred Akins, a thirty-year-old parlor car porter heading home from Grand Central Station, unaware that the white gangs were raging through town. Although a policeman rescued him from being beaten almost to death, a newspaper reported, he “barely escaped rougher treatment at the hands of the police.” The Jamaican-born Akins and fifteen other West Indians filed similar complaints with the British consulate.10 Wherever Williams was during the unrest, the enormous anxiety surely engulfed him as his family’s safety grew questionable: his wife and babies were on West 28th Street, and his parents, along with eight of his brothers and sisters, still lived at 474 Seventh Avenue near West 34th.

It’s uncertain if Williams yet knew either Bert Williams or George Walker of the comedy duo Williams & Walker personally, but news that Walker was attacked no doubt personalized the horror unfolding on the streets. Walker’s affable persona among audiences and in the theater community was already famous enough that several newspapers reported the shocking account: at about one o’clock at night, a horde of whites surrounded Walker and the comedy team’s secretary Clarence Logan on a streetcar at 33rd Street and dragged them out. Walker escaped the flail of their fists via Trainor’s Hotel, but Logan was overtaken and beaten terribly before he could escape into a drugstore, “which the proprietor locked and kept the mob out of.”11 For two days, similar attacks flashed throughout Manhattan’s West Side, from the West Twenties up to the black San Juan Hill enclave in the West Sixties. Not surprisingly, the wanton assaults prompted a rush to acquire weapons in kind: all over the Tenderloin, pawnshop clerks quickly sold out of their stocks of small arms as terrified blacks bought “everything from blackjacks to Colt’s 44s.”12

Springing into action, the Negro pastor Rev. William H. Brooks insisted that the real story of the riot was being silenced. In the following several weeks, he railed from his pulpit at the injustice being “whitewashed” by political authorities. “Colored people who break the laws must not expect sympathy from us,” Brooks told the crowd that filled St. Mark’s Methodist Episcopal Church—one of the city’s most notable black churches—but nor should they countenance lawlessness from Tammany’s police, who “are guilty of incapacity, brutality, and rascality.” He had spearheaded an initiative to collect signed affidavits attesting to police misconduct, and he readily ticked off a litany of damning charges from his list. Innocent men had been assaulted, nearly every case by officers on duty. Not a single “tough character” was among the victims, “but decent, honest, hardworking people.” Officers, instead of providing respectable helpless women their protection, had instead cursed and threatened them. Officers had kicked in the doors of upstanding colored businessmen who “were mercilessly clubbed upon their own premises.” Terrified men and women who threw themselves on the mercy of the law and sought refuge from the mobs in police stations were beaten by officers while getting out of patrol wagons. Officers recklessly shot at women and children looking on from windows. They drove men out of saloons to feed them to the mob. They shielded white offenders and abused innocent blacks. They broke into homes, rousted men and women from bed, and paraded them naked to the station. And “officers turned thieves and stole,” Reverend Brooks recounted.13

And then, when the mayhem seemed to subside, violence struck Williams and his family. On the evening of August 20, just days after the random attacks, twenty-five-year-old John W. Williams, Jr., Williams’s eldest brother, was found stabbed around the corner from their parents’ home. It was down the block from the famous Koster & Bial’s 34th Street music hall, whose management the Hashim Brothers—a noted Washington-based sibling trio of vaudeville house managers—had just taken over. The theater’s luck must have suddenly looked ominous as someone from Koster & Bial’s—maybe N. H. Hashim himself, who was in the house—put in an urgent call to Bellevue Hospital for an ambulance. A surgeon arrived to find the wounded man was already removed to a nearby doctor’s office. Struggling to stay conscious, Williams’s bloodied brother tried to explain what had happened: he’d been helping a drunken friend get home, but then the latter suddenly turned on him and stabbed him. His account satisfied the surgeon, who found a four-inch knife puncture in the young man’s abdomen; it raised eyebrows for the police, who could find no correlating cuts on his trousers or vest. But the gravity of Williams Jr.’s condition made the veracity of his story irrelevant, and the coroner was dutifully summoned to take an antemortem statement.14 As fate would have it, John W. Williams, Jr., recovered and lived eight more years, but his near-death experience was but another reason James Williams and other black residents viewed the Tenderloin with trepidation.

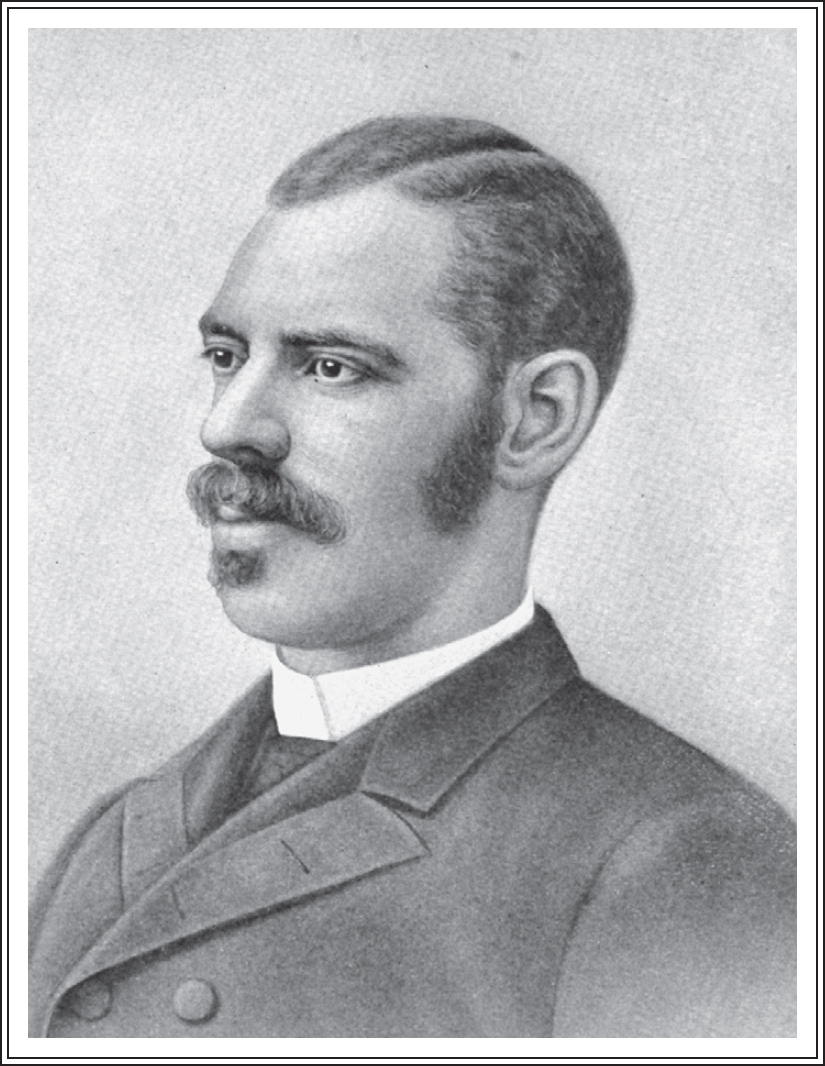

A strong influence for Williams, Rev. W. H. Brooks of St. Mark’s Methodist Episcopal Church condemned police lawlessness that fueled the West Side Riot in 1900, and conducted special sermons for Colored Elks and Red Caps. NYPL Digital Collections.

On the morning of Monday, September 3, 1900, Reverend Brooks and others organized the Citizens’ Protective League, to afford mutual protection and to prosecute the guilty in the aftermath of the West Side Riot. Its membership would reach five thousand. Brooks even found numerous allies among the white public. He challenged the police to answer the serious charges he had canvassed and conveyed. Dr. Hamilton Williams, the city coroner’s physician, publicly denounced Devery as the “procreator” of the riots “which convulsed a large quarter of our great city.”15 On the evening of September 12, the league held a public protest against the “whitewashed” inquiry into the sworn charges of police brutality, and to raise funds to prosecute the offending officers. The mass meeting was held at Carnegie Hall: the crowd filled the plush rows of orchestra seats, ascended the stairs to the tiers and boxes. The meeting opened with the singing of the national anthem and a prayer by one of the several clergymen speakers.16

On September 12, Reverend Brooks submitted an open letter on behalf of the league to Mayor Robert Van Wyck, beseeching a fair and impartial investigation. While condemning Harris’s act, and all lawlessness of the race, he was quick to add that “this crime, as black as it may be, does not justify the policemen in their savage and indiscriminate attack upon innocent and helpless people.” No monetary reparation was sought, Brooks emphasized, but rather that those officers, whom he assured the league could prove guilty, be convicted and ousted from the force. Failure to do so would otherwise encourage both the mob and the police to commit the same misdeeds, and would sow bloodshed as blacks inevitably took measures to defend themselves. The reverend deferred to the mayor’s influence to forestall all of this. “The color of a man’s skin must not be made the index of his character or ability,” W. H. Brooks wrote to Mayor Van Wyck, voicing the league’s appeal for common justice. On December 8 the inquiries concluded. The police were neither disciplined nor faulted.

Perhaps searching for some conciliation, Reverend Brooks found at least one unforeseen effect of the riots that the police and mobs never counted on: their disgraceful actions increased the demand for colored help. He told his congregation a white couple had just called on him intending to engage some colored servants. The woman said it was her first time, but that “she and some of her friends had been talking over the riots and they had concluded to give a chance to some of our people.” She knew a number of other wealthy white families now determined to do the same, from whom Reverend Brooks could relay an offer of “two good places now for two good girls.”17

Even if he hadn’t yet narrowed down his own goals, Williams was aiming, without cant or condescension, at some calling higher than domestic service. He understood that even increasing turn-of-the-century appreciation of Negro progress was predicated on an age-old assumption of service jobs as the prerogative of blacks. Despite the former prevalence of black men in such occupations during the 1870s and ’80s, their diminishing presence in hotels, restaurants, and homes by the turn of the twentieth century was obvious to some. White social reformer Mary White Ovington, who would later co-found the NAACP, recollected, “Frederick Douglass said that his color was an unfashionable one, and it is even more so now than it was in his time.”

It’s possible that Douglass’s wry sentiment, felt widely among fellow blacks, was unwittingly fostered by the man who would appoint him minister to Haiti: President Benjamin Harrison. In March 1889 the relocation of the newly inaugurated president to Washington, D.C., resulted in murmurings over his family’s imminent housekeeping arrangements: “Mrs. Harrison is replacing the servants in the White House, substituting white help for the negro servants who have had control of the domestic machinery there for many years.” Reports that the new first lady had drawn the color line at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue began to concern blacks well beyond the nation’s capital. Many blacks dependent on service occupations dreaded that, if white households north and south emulated White House etiquette, Mrs. Harrison’s example might result in loss of jobs and destitution.18

The Harrisons themselves did little to stem the rumor. Gossipy, uneven accounts cropped up in newspapers for days and weeks before other papers refuted the story. Some noted that at least three of the black domestic staff from the first family’s Indianapolis home had accompanied them to the capital. Other reports claimed the Harrisons employed more colored staff than any previous administration. The most impressive refutation came on November 28, 1890, when the Harrisons hosted a reception for a squadron of visiting Brazilian military officers at the White House. An awestruck account noted their “colored servants . . . not in livery, neither are they in the evening dress in which servants are often clothed in private residences. They stand about in plain business garments, and apparently have the success of the reception as much at heart as if they were the hosts.”19 It might hardly have mattered if rumors of the wholesale removal of “colored attachés” about the White House had been true. In the fateful interim between the first reports and recognition of their apparent baselessness, the fecund gossip had rekindled a latent prejudice that was thriving by the turn of the century.

Since 1900, Williams had seen old loyalties lose their adhesion. “Very few of the New York restaurants employ colored waiters,” a keen city observer reported, “the favorite waiters being white men.”20 Williams could attest to this through his father’s world; for quite some time, the advent of white foreign waiters from England and the Continent had edged out colored hotel waiters in first-class establishments.

In the spring of 1901, a resolution at the venerable Union League Club “to dismiss the colored help employed on the second floor and in the dining room” threw the organization into upheaval. Many saw the decision as betraying the original mission of the gentlemen’s club and its branches: the Union Leagues, or “Loyal Leagues,” had been founded during the Civil War to promote Union solidarity, the Republican Party, and the policies of President Lincoln. This New York chapter, which was especially proactive in its civic-minded missions, had initiated, organized, and outfitted the state’s first colored regiments. Nevertheless, the old racial prejudice they had shed blood to dispel still prevailed, even at the dawn of the twentieth century. Fortunately, some voting members at the Union League Club intervened and “overwhelmingly overruled” the votes previously cast to oust the black waiters—but not without stirring resentment. Outraged by the results, over a dozen governing committee members promptly resigned. Observing this controversy from the equally exclusive Lotos Club, the black waiters there penned a formal letter of thanks to the club’s manager, John S. Wise, who championed the cause of the Negro waiters in the midst of the Union League debate.21

It’s not known how long Williams’s father stayed on as a waiter at the Sturtevant House; some three decades since his first shift in 1873, the hiring prospects for the old colored waiters of his father’s generation were less promising than for at least a few young men in the flower shop nearby. In their place now, a few white girls waited tables in lunch rooms here and there, then made way, at an appointed hour, for white men to take over the dinner shift. And likewise a growing number of private homeowners were casually replacing their black American domestic servants, like a new floral centerpiece, with some white European variety.

Ironically, it was a particular European import about this time that would cast black New Yorkers of James Williams’s immediate circle in a fleeting, but glowing, light. Williams and Herbert Cummings, the chief shipping clerk at Thorley’s Roses, were but two of the numerous young colored men who staffed the chic floral operation. Williams and Cummings were of a type: both were born in Manhattan the same year and were of similar light complexion, medium height, and build—but Cummings was singled out on an eventful occasion.

On February 23, 1902, the popular Prince Henry of Prussia arrived in New York on the SS Kronprinz for a goodwill tour of several American cities and towns. Although Henry was not a ruling monarch—he was the younger brother of Kaiser Wilhelm II and the grandson of Queen Victoria of England—the prince was the first European royal to visit the United States. The occasion thrust New York into one of its most extravagant welcomes on record, most notably a gala performance in the prince’s honor at the Metropolitan Opera House—the “Yellow Brick Brewery,” as some mocked the industrial-looking pile—which was then located on Broadway and 39th Street. The prominent architect Stanford White completed a decorative overhaul of the theater’s interior, dividing the parterre with a vestibule, to reorient the royal box as the central focus. The Elblight Company installed nearly nine thousand incandescent bulbs of four candlepower (a third of them on a moveable sixty-foot-square drop curtain), an impressive feat of electrical technology for the time, achieved “without driving a single nail or screw, without breaking a single lamp or blowing a single fuse.”22

Not surprisingly, Charles Thorley was commissioned to execute the gala’s floral features, which rivaled the live entertainment on stage. The curtain rose on time at eight o’clock, and Prince Henry was expected to arrive at nine, fashionably late. The musical program unfolded under the notable batons of German-born Walter Damrosch, musical director of the New York Symphony Society; the Italian conductor Armando Seppilli; and Belgian composer Philippe Flon, who had conducted that country’s premiere of Puccini’s opera, La Bohème, two years earlier. The program comprised select acts from six operas—Lohengrin, Carmen, Aida, Tannhäuser, Le Cid, and La Traviata—for which over a dozen “luminaries of the operatic firmament” had agreed to perform.

The motley cast and crew in the wings were doubtless abuzz when word spread around 9:40 that Prince Henry’s entourage had at last arrived. Probably none of the artists were aware of the cause of the guest of honor’s distraction: he could not ignore the dazzling floral display that surrounded him. Arcing in both directions from his central seat were tier upon tier of flowers, the rows undulating over all the box and balcony fronts. Lush vines of southern smilax were “relieved with frequent bunches of azaleas and marguerites, and with stars of white lights shining through the green leaves.” Leafy streamers draped the sides of the proscenium, from the top of its opening to the boards of the stage, and were strewn throughout the great hall in festoons that gleamed with tiny white and green lights. The prince was overwhelmed. By the time La Traviata came up on the program, the act had to be omitted: the prima donna Marcella Sembrich declined to sing, having learned “the Prince had already left his box and part of the audience was following his example.”23 But Prince Henry would not quit the opera house before he knew just who was responsible for the floral decorations, which he thought were superb.

Probably James Williams was present at the opera house to help mount and break down the daunting floral installation—it must have required an army of hands—but it is not on record. Still, word that Thorley, an astute businessman, was not on the scene for his royal highness to pay a compliment was weirdly impressive. According to The World, “Mr. Thorley had left Cummings in charge,” so that was whom Prince Henry sent for. If the florist’s unceremonious absence was a show of faith in his employee’s consummate proficiency, it was aptly rewarded: Prince Henry offered the talented Cummings a position as his own florist when his tour through some of the other states brought him back to New York.

As towns across the country sprouted reception committees to welcome his royal highness, the black press noticed the conspicuous absence of black citizens. One Illinois paper asserted that committee officials “must have concluded that the ‘niggers’ must keep out of sight when Prince Henry arrives in town.”24 Another, in Kansas, urged that Prince Henry “be given a chance to see the Negro in some other capacity than a servant.”25 But it came as a surprise to blacks and whites alike to learn that Prince Henry was a bit of a Negrophile who had given some advance thought to aspects of black American life he wanted to explore. Black readers who followed the princely itinerary in the dailies would have noticed occasional ad hoc adjustments that revealed his royal highness as at least an inadvertent champion of the race.

All along the itinerary, members of local German societies quite naturally turned up for the rare opportunity to celebrate their Teutonic heritage. Indeed, when Prince Henry’s special train arrived for a fifteen-minute visit to Nashville, Tennessee, some of the seven hundred ticketed townsfolk who greeted him at the depot were all done up in their Tyrolean Sunday best. Eager to indulge any matter of royal caprice, they were no doubt surprised to learn that an explicit request had been wired: “Prince Henry will be pleased to hear Jubilee Singers during his stop at the Nashville station.”26

Back in 1871 the Fisk Jubilee Singers, of the town’s historically black Fisk University, had introduced the wider world to slavery-era “plantation songs,” which had been preserved in the American musical lexicon as Negro spirituals. Their renown as a musical group lent plausibility to the German royal’s pressing request, but few would have guessed at the prince’s more sentimental motive: when he was about fourteen, the Jubilee Singers had performed those very melodies in the theater of his family’s royal palace at Potsdam.

Though over a quarter of a century ago, he longed to hear them again. In fact, his first request upon arriving in the United States was to hear “some of the old Southern melodies, if possible, sung by the negroes.” According to Rear Adm. Robley D. Evans—the official American chaperone to his royal highness, who received him in New York—Prince Henry confided “he was passionately fond of them, and had been all his life—not the rag-time songs, but the old negro melodies.”27 The prince was once again deeply moved by some of the old spirituals, of which “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” had been given as a preference. However, the combined arrangements of Nashville’s mayor and Fisk’s president exceeded the Prince’s wish: the soprano leading the singers was Mrs. Ella Sheppard Moore, “who led them at the time the Prince heard them in Germany” and was the only member remaining from the original company at its inception in 1871. Enraptured, Prince Henry rose and grasped Mrs. Moore’s hand (said to be the only hand he shook at Nashville) as he recalled the joy the group’s visit had brought to the entire royal family at Berlin.28

Back in New York, Prince Henry made a point of attending two concerts of the visiting Hampton Singers, in a reception hall at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel and at Carnegie Hall, respectively. At the former, he turned excitedly to Admiral Evans to ask, “Isn’t that Booker T. Washington over there?” Evans, somewhat surprised, confirmed that it was indeed the famous Negro educator from Tuskegee Institute. The prince urged Evans to introduce him. “I know how some of your people feel about Washington, but I have always had great sympathy with the African race,” he said. “I want to meet the man I regard as the leader of that race.”

The two men talked for fully ten minutes. “Booker Washington’s manner was easier than that of almost any other man I saw meet the Prince in this country,” Evans recalled. Prince Henry left overjoyed by Washington’s promise to send him published copies of the old Negro songs he had cherished since his German boyhood,29 but in the meantime he happily discovered the new Negro music at a saloon on West 53rd Street. The colored musicians, singers, and dancers at the Hotel Marshall’s cabaret were blithe to share their new repertoire of vaudeville “rags” and show tunes to the attentive royal fan.30

Certain loyal followers of Prince Henry’s itinerary read the papers with personal interest. On March 11, 1902, Cummings was to accompany his highness back to Germany aboard the SS Deutschland as Thorley’s official representative. Preparing for their friend’s departure at the flower shop, Williams and his co-workers understood it was no trivial matter for their boss to give Cummings a $700 (about $19,000 today) stipend for expenses and place him in charge of an estimated $6,000 worth of flowers (about $161,000 today). Approximately fifteen thousand fresh blooms—American Beauty roses, winter roses, sprays of lilies of the valley, orchids—were painstakingly picked, swathed in moss, and laid out in the ship’s hold in iceboxes at the last moment.31

Once the Deutschland set sail, Thorley’s staff pored over the reports from Cummings, who was now essentially the personal floral steward to the Kaiser’s brother. “Every morning I supplied the Prince’s stateroom with fresh flowers and at each of the three meals the decorations of the royal table were changed,” Cummings said, adding, “The Prince talked to me a lot about the greatness of the United States.”32 Cummings’s overseas adventure was extraordinary: he returned with the prince’s gift to him of a royal letter and a $500 gold watch with diamonds encrusting its face. Thorley would eventually make him shipping clerk for his famous House of Flowers shop at Fifth Avenue and 46th Street. But even after he returned, Cummings was somewhat independent of the bustling district of the shop: he was living up at 4 West 134th Street in Harlem. For Williams, that remove may well have added to the place’s allure.

Whether Williams heard it directly or not, he seemed to take something to heart that Reverend Brooks later recommended. The pastor spoke fervently of building up the race through self-reflection, political consciousness, financial stability, and even real estate: “Buy property, and buy more property, and use your means in the ways of righteousness.”33 He railed impatiently on a later occasion against the disheartened of the race who preached expatriation: “The ship is not to be deserted because of stormy weather. If we cannot go forward, let us mark time. Here we have toiled, here our dead lie sleeping, and we have no other home. But we claim here more than food and clothing—we claim the right to be honest and industrious.”34 Perhaps Brooks or Cummings or even Thorley inspired Williams’s own diligence.

Around 1903 Williams moved his family out of the Tenderloin, and some five miles farther uptown. Though he hadn’t the means to buy property yet, he was a part of the first great wave of black renters to venture to Harlem. How Harlem’s white landlords begrudgingly came to open up their restricted properties to “respectable colored tenants” is a story of legend. The advent of the city’s first subway, in 1904, triggered an explosion of speculative development in Harlem. Block after block, a building boom of new apartment houses, anticipated an influx of white tenants. But those white tenants did not come as envisioned, so many an overzealous builder found himself in an unscripted financial dilemma. The predicament offered a decided advantage to such pioneering and savvy African-American realtors as Philip A. Payton—often extolled as “the father of Harlem”—who now persuaded crestfallen white property owners and managers to accept black tenants if they wanted to avoid financial ruin. He also swayed a number of blacks to consider investing—if not through stock purchases, then through foresight—in his newly incorporated Afro-American Realty Company:

James and Lucy Williams, circa 1903, about when they moved from the Tenderloin to Harlem, with children Gertrude, Wesley, and James Leroy (“Roy”), about a year old, on his father’s lap. Charles Ford Williams Family Collection.

Beyond a reasonable doubt, the completion of the new Pennsylvania Depot will bring about a great change in the character of the [Tenderloin] neighborhood now surrounding it. . . . This section is largely inhabited by our people. Where are they going when this and other changes take place and they are driven out?35

By 1905 James H. Williams was among those pioneering arrivals to Harlem, having moved his family to 18 West 134th Street, a five-story brownstone tenement between Fifth and Lenox avenues.36 Though it was not one of Payton’s buildings, the black property manager, Clarence Hutchinson, worked and lived in the building, which boosted the place’s sense of security and respectability. However, the neighbor who lent this new uptown address the most prestige was Jesse A. Shipp—who would be called the “Dean of Colored Showmen”—a Broadway star who’d come to live in Harlem, “the choicest location of all the big [Afro-American] actors in New York.”37 Shipp co-wrote and appeared in the recent hit In Dahomey, the first African-American musical to be performed on an indoor Broadway stage. It affiliated him with “the highest rank of actors of his race” who were then influencing American theater, including Bert Williams, George Walker, Aida Overton Walker, Will Marion Cook, and Paul Lawrence Dunbar.

Whatever their disparate vocations, Williams and his new neighbors personified essentially similar quests for self-betterment, familial security, and prosperity and, as Reverend Brooks had invoked, to “uplift the race.” Their example induced thousands of other black families to pull up stakes from Manhattan’s scattered “black belt” enclaves in Greenwich Village; in Chelsea; the vibrant West 53rd Street spine of the Tenderloin (today’s Penn Station and Hell’s Kitchen areas); and in San Juan Hill (today’s Lincoln Center area), a black neighborhood in the West Sixties, whose nickname was purportedly inspired by the “colored” 24th U.S. Infantry that distinguished itself during the Spanish-American War in 1898. The uptown relocation of Williams and other black families, in turn, encouraged the Great Migration of rural southerners to the urban centers of the North, prior to World War I. The linchpins of this extraordinary demographic shift to Harlem—a once-sleepy white suburb, suddenly revitalized as the capital of America’s “New Negro” race—were a wide array of African-American business folk, artists, entrepreneurs, and others whose professional circles now regarded Williams, in his new capacity at Grand Central Station, as a man of position.