CHAPTER 4

Fraternity and Ascendancy

Mr. Williams holds one of the most responsible positions—as little as it is known—at this great railway station, that of chief of the Red Cap attendants.

—JOHN E. ROBINSON, 1909

Even before it selected an architect or determined a design, the New York Central Company started building its new $200 million terminal complex around the old Grand Central Station. On July 18, 1903, workers broke ground on East 42nd Street and, to maintain regular service during construction, adapted the Grand Central Palace exhibition hall on East 43rd Street into a temporary terminal. For the next ten years, as crews executed their strategic demolitions and elevations, Grand Central Station carried on as the seminal railroad gateway to the metropolis.

For his part, as general passenger agent, George H. Daniels continued to welcome travelers with ever-freshened promotional enticements: “Nineteen red-cap attendants in handsome uniforms meet all incoming trains.” Numerous publications reminded travelers that these attendants were at their disposal for free, being employed by the railroad company. Without giving salary figures, the New York Central’s Four-Track News—an onboard magazine that Daniels launched two years earlier, and that would become Travel magazine—suggested that Grand Central Station’s Red Cap attendants earned twice as much as counterparts elsewhere in the company’s network, even on par with “the average railroad conductor.” Whether it was true “that passengers can here get good service without feeling obliged to tip the porter,”1 a railroad attendant might forget to reiterate it. Despite Daniels’s brochure parlance, one might wonder if a white attendant’s salary was truly lucrative enough to dull his aspirations to a higher position.

Of course, for Williams and other members of the race in general, the challenge of securing a regular salary through gainful employment was all too familiar. The sociologist Mary White Ovington (who actually knew Williams’s sister Ella through their mutual connection to the Quaker-run Colored Mission) was among numerous white “progressives” who were elucidating the troubling social conundrum to the broader public. A prolific informant on the subject of Negro family life in New York, Ovington helped further the subject’s topical interest. Numerous black civic leaders, ministers, and teachers would soon endorse her important mission to investigate employment opportunities, housing conditions, and the efficacy of relief agencies pertinent to the race.

Ovington cited countless cases of trained and qualified black women whose color alone routinely denied them access to trades above laundry work or domestic service: “They cannot be saleswomen, stenographers, telegraphers, accountants or factory workers, because in the great majority of these positions they would be obliged to work side by side with whites.” She also pointed out black professional men who were acutely aware that, whatever their status amid their own people, no credentials ensured them positions in trades obliging their constant interaction with white peers or clients. “For this reason we seldom find a colored architect or engineer or electrician,” she observed, “while there are plenty of doctors, lawyers and clergymen.” But brushing aside her own many citable caseloads, Ovington judged there were “really few people who entertain this strong race prejudice.”2 She hazarded that if employers simply refused to listen to biased complaints, racial tension would soon disappear from the workplace. Her optimism remained to be tested.

In anticipation of the new station being built, the New York Central hired a Negro to the Red Cap attendant service team. “I was the first colored man ever employed at Grand Central as a red cap,” Williams averred many years later. The all-white workforce that Daniels created eight years earlier would soon become almost all black. Williams recalled he was hired to replace a white man named Walsh, who had been promoted to a clerical position in Grand Central’s Information Services.

If in most occupations breaking the color line was inherently controversial, Williams’s hire did not noticeably touch off any polemical objections. And though white workers often adamantly refused to work alongside black ones, instances of whites and blacks working together tolerably were not unknown. Some employers sympathized with social reformers like Ovington and, defying the prejudiced indignation of their white workers, chose to “stand by their colored employees and refuse to dismiss them.”3 But the virtual absence of reports soon after he replaced Walsh suggests that Williams’s hire was but the first step of Grand Central’s orchestrated stride toward a complete racial overhaul of its Red Cap station attendants. If the white attendants made any concerted protest over a colored man’s admission to their ranks, or objected on grounds of a perceived threat to their incomes, it did not reverberate in the press. A better guess is that the ensuing rapid attrition of other white attendants was due to their rise, as with Walsh, into other, more highly regarded departments of the terminal.

Although Daniels had mustered a dozen white men into the station’s Red Cap attendant service in 1895, most educated white men shunned the job as too menial. A white attendant’s mandate to relieve encumbered ladies—and increasingly gentlemen, too—no doubt heightened his popularity with those he assisted. But every valise, hatbox, and baby thrust at him emphasized the humbleness of his position and effectively nullified Daniels’s earlier claim that “they are not porters”—a term the word attendant did not really displace. Perhaps the constant hauling of others’ property reminded him that this job was a low echelon of the railroad station’s workforce hierarchy. Yet if a white attendant was apt to bemoan self-comparisons to the colored Pullman porters on the train, or to the baggage smashers on the street, he could reasonably hope to ascend to another position, even if unschooled, simply because he was white. It was unthinkable, considering the many rigidly obeyed racial barriers, that Daniels would nonchalantly replace a white attendant with a black one. Even without knowing who vouched for Williams—though Thorley seems the most plausible candidate—Daniels would certainly not have risked the company’s censure by hiring a Negro with less than the highest recommendation.

Though Walsh’s vacancy might have given him an in, Williams understood the palpable boundaries of the terminal’s color line that debarred him from opportunities that were available to his white predecessors: as Negroes, he and others who might follow him could not count on promotions. How apt now was Reverend Brooks’s challenge of a few years before. “Work may be difficult to secure,” he’d said, “but if we cannot get what we want, let us take what we can get.”4 Williams could surely imagine it to be auspicious for the race to corner this disdained job category, as a sort of bird in the hand until something superior was in the offing. Later claims that he convinced the eminent New York Central railroad company to give Negro workers the Red Cap attendant franchise are less than persuasive. Indeed, irrespective of Williams’s sentiment, the company was hiring blacks rapidly enough to suggest that it was already contemplating a full revision of its Red Cap attendant system into one that racial caste defined as a porter system. Indeed, the byword of “porter” or “Red Cap” quickly supplanted that of “attendant,” which all but vanished.

For some thirty-five years, colored sleeping car porters had been serving Pullman cars of the New York Central and other railroad lines across the country. Negro station porters, a logical extension of Negro sleeping car porters, would have obviated company concerns about white attendants who, disgruntled by their lowly position (perhaps aggravated by being nevertheless referred to as porters), were less inclined to hustle than black attendants striving for job stability. Whether by happenstance or by design, Grand Central Terminal’s new all-black Red Cap porter system rapidly swayed a similar racial shift in railroad stations across the country. Though employing blacks may have been less altruistic than intuitive, for it assigned blacks the same genre of jobs to which they had been traditionally relegated: service.

The Grand Central Station workforce transformed precipitously. By the spring of 1904, the Red Cap staff, which Williams had integrated the previous year, was almost exclusively black. (The notable holdout was Milt Newman, apparently as novel for being Jewish as for being white, who had started in 1900 and continued into the 1940s.) Grand Central’s hierarchy was not unlike that of other U.S. railroad stations at the time. It employed multiple thousands of people. Williams and the other Red Caps were supervised by the stationmaster, who in turn fell under the jurisdiction of the terminal manager—a position that was described as a “neutral terminal official” who served the New York Central and the New Haven companies equally. Under his control were four principal departments of the station: seven stationmasters, the gatemen, the information service, and the Red Caps. By dint of their race, the last were ineligible for promotion into the other departments.

If advancements were impossible, some Red Caps discovered other ways to improve their lot at one of Grand Central’s most coveted posts: the Vanderbilt Avenue entrance, a principal point of arrival, on the west side of the station. Since the company paid them only sixteen dollars per month (less than it had paid the white porters), they soon figured out how to make up the difference—and at a profit. By turning up the charm as they hustled, they earned tips from travelers, often trebling their small salary. But upon learning they were doing so, the stationmaster docked the men from the payroll altogether and insisted—over the porters’ strongest objections—they would have to get by only on tips from now on.

In defense of his retrenchment, the stationmaster informed the men that the company considered their services to be inessential and actually “only consented to have them stay out of pure goodness of heart.” But was that true? No record places Williams at the Vanderbilt entrance, although he was the likeliest to have been if the seniority system that entitled men to that post in later years was already in effect. At any rate, Williams knew the stationmaster’s baseless barb contradicted everything he’d ever heard the company say to promote the free Red Cap attendant service, and which it would repeat for years. The comment more likely revealed a bitter recognition that white Red Caps were from a bygone era. Williams and the other Red Cap attendants could easily see through the stationmaster’s indignation. His subsequent action was too familiar to them, merely another instance of exploitative supremacy over black workers—who could not advance or transfer from redcapping like their white predecessors.

While the New York Central patently discouraged passengers from tipping, the stationmaster hadn’t pointedly objected to Red Caps taking tips per se. It rather seemed he resented these Negro porters being so successful.5 And some were astronomically successful, according to one former porter. “The salary as a Red Cap was $32.10 a month, and I was saving $300 a month,” Jesse Battle recalled of his last days as Williams’s assistant chief in 1911, before he became the first black police officer in Greater New York. “I was making three or four hundred a month as a Red Cap.”6

By 1905 Williams’s hire may have sparked predictable resentment from the stationmaster. It perhaps resonated elsewhere, too: a Brooklyn pharmacist mockingly “rigged up a little darky with a red cap and yellow coat” that summer to promote his shop.7 But it surely inspired others: William Ernest Braxton’s painting, The Red Cap, in the Brooklyn Colored YMCA’s first annual exposition of American Negro artists that fall, visually codified the Red Cap railroad porter as an iconically Negro occupation.8 And a story serial in the Ladies’ Home Journal that same year began: “When we got to the Grand Central Station to start for Newport we had a number of the delightful café-au-lait-colored porters in gray livery and red caps to help us with our bags and things getting into the train.”9 Maybe one was Williams, who toted baggage during the station’s expansion over the next few years. If chivalry was dead, as some wistfully conceded, then Jim Crow servitude would have to make do.

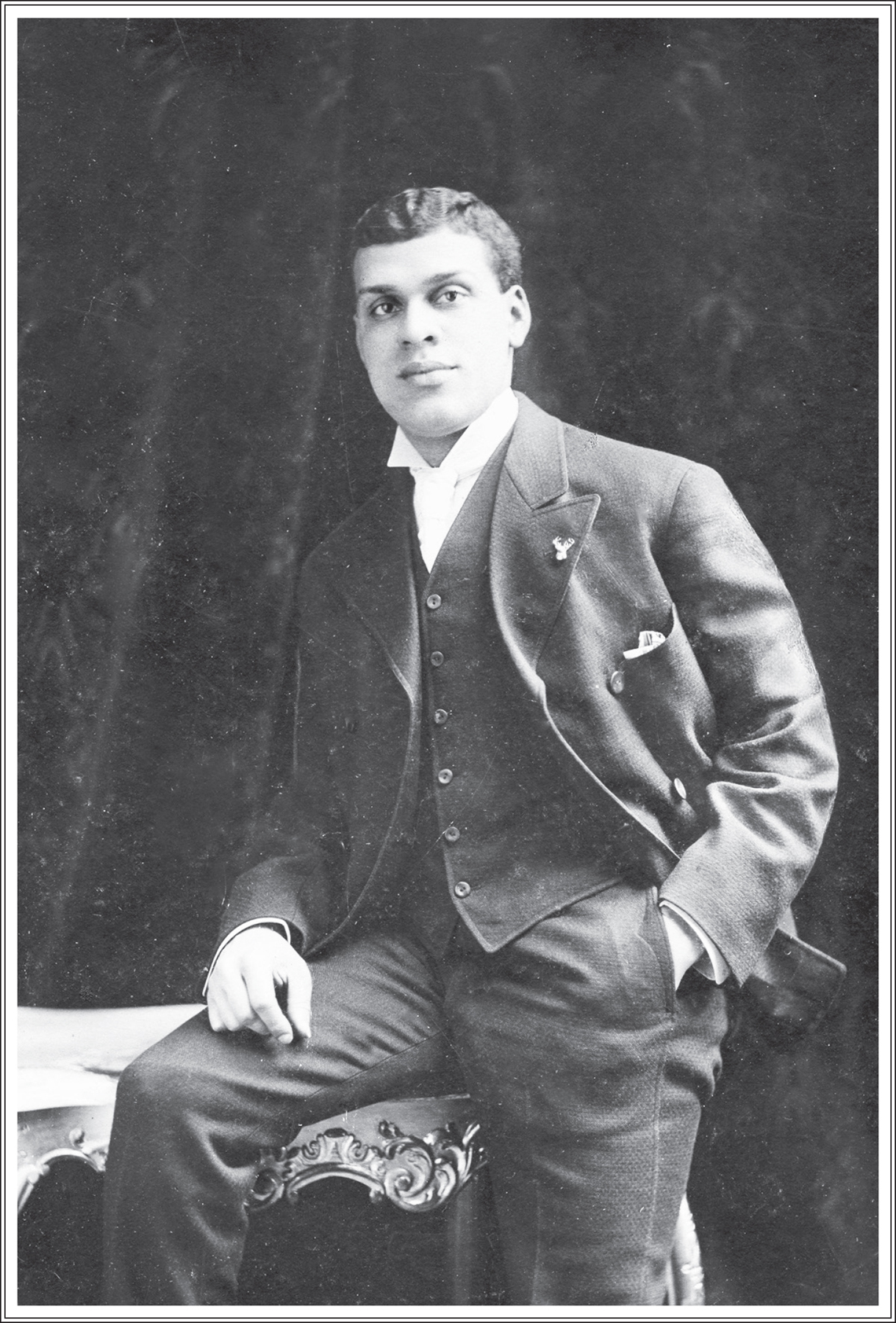

Probably sometime in 1905, Williams went to sit for his portrait at the prestigious photography studio of Otto Sarony, at 1177 Broadway near 28th Street. Sarony’s shop was directly next door to Thorley’s, and Williams had likely known him through his duties for the latter.10 What occasion prompted this sitting is not known, but the full-length portrait seems telling: smartly attired in evening wear, Williams dressed not to reflect his job as railroad attendant but more likely to convey his readiness to claim some promising prospect in the offing. Though not dressed for work per se, this broad-shouldered young man in his twenties was apparently suited for something of considerable importance, something that very likely had to do with his recent affiliation with a particular fraternal order.

For this photo, Williams had slid tight the knot of his white silk cravat to the white batwing collar that splayed beneath his fair brown throat. He fastened the six vest buttons of his well-tailored dark three-piece tweed suit, and he tucked a patterned silk pocket square into the coat’s left flank pocket. Williams could not have been unaware, as he poked a tiny brass pin into his lapel, that many took exception to the ornament. The shiny antlered head was the emblem of the Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks of the World—IBPOEW, or Colored Elks. They were part of the phalanx of black American fraternal organizations that had been forming since 1787, when Prince Hall of Massachusetts chartered, and became namesake of, the first Masonic lodge for members of African descent. As Williams was aware, bands of white Elks often set upon any unwary black man who dared to sport their beloved mascot on his own lapel—and it was a litigious offense in New York. In the photograph, the modest but potent little symbol suited Williams, both as an adornment and as a badge. A comb had marshaled the unruly curls of his raven hair. His calm, doe-eyed face already exuded the confidence and goodwill of an ambassador—a sort of minister without portfolio, gamely awaiting an assignment.

James H. Williams, in an Otto Sarony Studio photograph, circa 1905. Williams’s “antlers” lapel pin defied a law—which his lodge overturned in court—barring blacks from wearing Elks insignia. Charles Ford Williams Family Collection.

About this time, in 1905, some local acquaintances had begun raising Williams’s interest in the Elks. That year realtor Sandy P. Jones, one of Harlem’s increasingly patrician Negro colony along West 134th Street, took notice of Williams, a fairly recent person of note on the block. Jones surely knew it was Williams who broke the color line at the august Grand Central Station, and was intent upon making the fellow’s acquaintance. Jones was not just a real estate man—he was connected to black real estate royalty. He was a stockholder and member of the board of directors of the Afro-American Realty Company, the firm established by the putative “Father of Colored Harlem” Philip A. Payton, Jr. With the discerning eye of a cobbler-turned-broker, Jones now sized up his neighbor for a purpose. He happened to be the Exalted Ruler of Manhattan Lodge no. 45, a fraternal order of the IBPOEW, with a tireless mission to institute new lodges in towns throughout the Northeast. To Jones, this James H. Williams appeared a worthy race man to recruit.

Jones’s invitation was flattering and perhaps acknowledged the rarity of a colored man flourishing from Thorley’s flower shop to Vanderbilt’s railroad terminal. But Williams could not have savored that invitation without tasting its potential danger. The very existence of the Colored Elks, as the order was best known, was the bane of the older white fraternity, which was on the whole unbrotherly—indeed, it was litigious and vindictive. Yet knowing the Colored Elks sought only the best characters for membership would surely have stoked Williams’s enthusiasm about them. Williams was already known in fraternal orders. He and his father both counted among the “gentlemen of standing and integrity” of Ivanhoe Commandery no. 5, under the Knights Templar, a Freemasonry-affiliated order with a specifically Christian-based membership requirement. The Ivanhoe’s drill corps was widely praised for its demonstrations, at black social functions, of intricate and precise military maneuvers.11 James was also a member of the Manhattan Lodge of Odd Fellows, the Royal Arch and Blue House Masons, and Medina Temple, so the Manhattan Lodge of Elks was probably not a hard sell for him.12

Given Williams’s vocation, he had very likely heard Colored Elkdom’s creation story—which, coincidentally, unfolded from the railroad. One Billy King—an impresario who worked a backup job as Pullman buffet man between theatrical bookings—picked up a certain book that some white passenger had left behind on a New Orleans–to-Cincinnati train. Unimpressed, he tossed it into a linen locker. A. J. Riggs, the porter of the same Pullman car, found the book but, unlike his colleague, lost himself in page after page of its strange accounts of secret rituals. The white passenger who had so carelessly left this mysterious volume on the train turned out to be the Grand Exalted Ruler of the Elks, who soon reported his precious lost item to the Pullman Company. Upon investigation, the book was discovered, and King, who had originally found the book but failed to properly turn it in as lost, was suspended. Riggs was fired, but the book’s magic had already turned him in a fatefully creative direction. He and his friend B. T. Howard organized the country’s first chapter of Colored Elks. As a result, White Elks embarked on a campaign of costly lawsuits that endured for years.

Founded in 1898, the still nascent order of Colored Elks had fashioned itself upon the bylaws and principles of its white predecessor. As tensions mounted between the two organizations, the Colored Elks quickly pointed out that “the seven original members, who constituted the first lodge in New York City, February 16, 1868, did not have any ‘Jim Crow’ annex clause in their By-Laws and Constitution”; rather, it argued, “good Southerners” had added the clause later.13 For their part, on June 9, 1868, the jolly good Northerners organized a Minstrel Festival at New York’s Academy of Music to benefit their new Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks. Revealing their own racial prejudices, the publicity promised to feature “Ethiopic arias”—using a commonly exotic nickname for Negro—and a popular headlining act named Emerson, Allen and Manning’s Ethiopian Minstrels.14

By the early twentieth century, Colored Elkdom had grown rapidly into a powerful movement for financial and spiritual self-empowerment in black communities across the country. Manhattan Lodge no. 45, organized in the fall of 1904, was the first on the island borough.15 The lodge enlisted Williams during its distinctive emergence in the struggle for black civic equality, when the Colored Elks constituted the institutional forerunners of the modern civil rights movement. Whether purposeful or intuitive, the lodge probably valued Williams’s practical experience from working at Thorley’s and Grand Central Station: both jobs called upon his convivial forbearance under pressure from an often demanding public.

At the time, white Elks societies across the country were strong-arming black Elks, whether physically or by systematically forcing them into litigation. In New York, Assemblyman William J. Grattan, a chief ally of the white Elks, introduced legislation that made it a misdemeanor statewide to wear an order’s copyrighted emblem. Grattan feigned ignorance that black Elks existed at all, but members were certain the newly enacted law was targeted at them. On April 12, 1906, police arrested one of Williams’s Manhattan Lodge brothers, Oldridge R. Johnson, for wearing his Elk lapel pin. Johnson was arraigned for violating three counts of Section 674-A of the Penal Code, or the “Grattan bill.”

After a few adjournments, on June 19 Johnson’s case went before the court of general sessions, where about three hundred white Elks filled the chamber. Three justices examined the evidence put before them. They compared the names of the two societies—the “Benevolent Protective Order of Elks of the United States” versus the “Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks of the World.” They examined the white Elks’s copyrighted button, which bore an elk’s head with the letters BPOE above the antlers. Then they examined the colored society’s button, with its abbreviation, IBPOEW, on the same plane as the antlers. The justices conceded the similarity but nevertheless threw out the case on the grounds that the word white in the white society’s constitution was an impropriety: they held that, being black, the Negro society could not practice a deception. They also determined there to be no evidence that the colored society had willfully violated any provisions of the white Elks’ constitution or bylaws. Accordingly, they upheld the Colored Elks’ right to adopt and wear the emblem of any secret society that exluded their membership. The justices acquitted Johnson unanimously.16

By now Williams was a conspicuous member of the Manhattan Lodge of Elks, with essential organizational importance. He was elected Esteemed Leading Knight, making him second in command in the hierarchy of Manhattan Lodge officers, after Exalted Ruler Sandy Jones. He was keeping enviable company: “Mr. Sandy P. Jones, the present Exalted Ruler, is a man of good executive capacity and a skillful parliamentarian. It is mainly through his efforts and ability that the lodge holds the enviable position it does in the order of Elkdom.”17

Another officer of the tribe (as lodge members called themselves), holding the rank of Esquire, was Jesse Battle.18 Although Williams was only a few years older, he regarded his friend as something of a protégé: Jesse had followed him as a Red Cap at Grand Central in May 1905. Not only did Williams and Jesse share both employment and Elks membership, their families grew as extended relations to each other in Harlem as neighbors, mutual house guests, and even occasional traveling companions.

As fellow officers and friends in the Manhattan Lodge of Elks, Williams and Jesse helped to coordinate a pivotal event in the lodge’s maturation: On June 8, 1906, the First Annual Picnic and Summernight’s Festival took place at Sulzer’s Harlem River Park. Williams, on the event’s floor committee, mingled and made introductions among the vast, interchanging crowd as it enjoyed the music furnished by Hallie Anderson, one of the preeminent dance music leaders of the black society circuit whose full orchestras, not uncommonly at the time, were often mixed with white musicians.19 The event was a formality, albeit a judicious one: it set the stage for the Manhattan Lodge to impress and garner support from Negro Harlem society. It also gave the two-hundred-member Manhattan Lodge visibility in the eyes of the national body, Grand Lodge of the IBPOEW: it showcased the fledgling lodge as having the political gumption to host the seventh annual session of the IBPOEW Grand Lodge that would take place in Brooklyn two months later. That late-summer national conference would constitute a signal turn in the Colored Elks history.

Indeed, Williams’s lodge was facing a newly dispiriting battle against the Elks’ national leadership. “Trouble is hotly brewing in Elkdom for Grand Exalted Ruler B. T. Howard,” the New York Age wrote of the Grand Lodge’s first titular head, who, it opined, “got cold feet about meeting in Brooklyn.” Before Johnson’s trial, Howard had effectively capitulated to the threat of the Grattan bill. Citing New York’s statewide prohibition of Colored Elks wearing pins and badges, he declared it “wise and beneficial to move said Grand Lodge to the city of Columbus, Ohio.”

Howard’s overcautiousness struck many members as an impolitic show of weakness, not to mention a lack of solidarity. Many were also irate that he presumed to usurp the governing authority of the Elks body: he had not consulted any of the numerous member lodges whose votes at the Grand Lodge session in Washington the previous year had determined the location of this year’s session. The Manhattan Lodge, duly galvanized by the triumphant outcome of its costly legal defense, lost patience with the Grand Exalted Ruler’s unilateral decision. Joined by Brooklyn Lodge no. 32 (the mother lodge of the Elk order in New York State) and Jersey City’s Progressive Lodge no. 35, the three lodges together challenged Howard’s one-man rule. The Grand Exalted Ruler retaliated by suspending all three for insubordination, which prompted dozens of other lodges to defiantly close ranks against him.

On August 28, 29, and 30, 1906, the seventh annual Grand Lodge session took place in Brooklyn as planned. But the estimated “one hundred lodges, with an aggregate membership of 12,000 American citizens” at the borough’s Sumner Hall, formed the dissenting faction of a schism in Negro Elkdom: the matter of deposing the autocratic Howard topped their agenda.20 The two factions split, and Dr. W. E. Atkins was installed as Grand Exalted Ruler of the new faction.

After the session adjourned, the Manhattan Lodge to which Williams belonged gave “the delegates an opportunity of seeing Coney Island and other points of interest.” At Coney’s Luna Park, many would have been eager to see, among its myriad diversions, the artist E. J. Perry, “the negro silhouette cutter” who limned portraits on the spot with a pair of scissors in lieu of pen and ink. The Manhattan Lodge also treated conventioneers to “trolley cars and a band of music.” Even lacking a song list, the high quality of the entertainment—no doubt dance music of symphonic proportion and style—may be deduced from the names of a few of the Manhattan Lodge members in attendance. James Reese Europe was a bandleader nonpareil who a few years later would found the Clef Club Orchestra and during World War I would become lieutenant leader of the 369th U.S. Infantry “Harlem Hellfighters” Band. Arthur “Happy” Rhone was an orchestra leader who would become the principal Harlem nightclub owner in the 1920s. And both Wilkins brothers would gain renown for promoting and giving succor to black performers: Barron as a hotelier and cabaret owner of Harlem’s Exclusive (né Astoria, later named the Executive) Club, and Leroy as owner of the Cafe Leroy.21

By the fall, Williams was clearly ensconced in the inner circle of the country’s largest black fraternal lodge. On the evening of November 22, Manhattan Lodge no. 45 gave its first Grand Annual Ball and Reception, again with Hallie Anderson’s orchestra. Williams served on the arrangements committee and was able to secure the Grand Central Palace as the venue.

By January 26, 1907, Manhattan Lodge no. 45—having emerged from the split with the Grand Lodge’s Howard faction a few months before—was newly rechartered and incorporated. Among the eleven names appearing on the new charter were the indefatigable Sandy P. Jones, James H. Anderson (who would found the New York Amsterdam News two years later), and James H. Williams as trustee.22 That spring the lodge elected Williams its treasurer, and he also officiated as grand treasurer for the West Chester Lodge no. 116 in Tarrytown. “Forty good men,” the IBPOEW’s recruitment philosophy proclaimed, “are far better than a hundred bad or unreliable men.” Williams thrived in this good company.23

Late on Sunday, December 1, 1907, Williams and several dozen other finely dressed men gathered on West 53rd Street as St. Mark’s Methodist Episcopal Church let out its regular evening service. The gentlemen exchanged brief greetings with the exiting parishioners and, at the behest of Reverend Brooks, helped themselves to the just-vacated seats. These members of Manhattan Lodge no. 45 of the IBPOEW had come in force to formally issue a proclamation: by authority of the factional Grand Exalted Ruler, Dr. W. E. Atkins, the first Sunday in December of each year was designated “Elks’ memorial day,” to be commemorated thereafter “by every lodge of Elks to the memory of our departed brothers.” James H. Anderson, who replaced Sandy Jones as Manhattan Lodge’s Exalted Ruler, delivered the opening address; the Elks’ Quartette rendered “Nearer My God, to Thee”; a roll was called, revealing 187 of the full membership of 292 in attendance; and Reverend Brooks delivered his second sermon of that evening, which he closed with a benediction: “I am glad that you came here tonight. I wish you success, for I know that you have difficulties.”24

The difficulties that Reverend Brooks referred to were the battles that the Elks would persistently face on behalf of the race. From the collective fraternities of Elks, Odd Fellows, Masons, Knights, and other orders, including their women’s branches and counterparts, Williams surely drew ample experience and confidence to shape his “uplift” mission of community building at Grand Central Station. It was a mission that other family members were striving to carry out in their own way.

Around the time Williams was joining the Elks, his wife Lucy delivered their fourth child, Dorothy; while his sister Ella bore her and her husband’s first child, Lloyd Meegee Cofer III. Ella and her husband were still fairly newlywed when their boy came. On January 6, 1904, she had been twenty-two and Lloyd Cofer, Jr., nineteen when they stood before Reverend Sill at St. Chrysostom’s Chapel (where James and Lucy had wed seven years before). Despite the joy of Lloyd III’s birth the following year, the young couple’s marriage was tragically cut short a year after that by Lloyd Jr.’s death.

The passing of Williams’s brother-in-law drew an affecting response from Mary White Ovington, who was gaining wider notice as a keen social reformer. Before she would co-found the NAACP in 1909, Ovington gave deference to the deep, invaluable friendships she made among black New Yorkers—like the Williamses and Cofers—in the course of her research and prolific discourses on Negro family life in the city. That she so generously eulogized Lloyd Cofer in Colored American magazine perhaps softened Ella and her family’s personal sorrow—if that were even possible at the time—but Ovington was their good friend, who had known the two young sweethearts, and their ambitions, for years.25

Williams’s widowed sister had a life just as busy as his, albeit in religious circles. Though Ella and Lloyd Jr. were active in pious church work, they also were ardent race workers. The couple had met as teenagers at the Colored Mission on West 30th Street, a Quaker philanthropy established just after the Civil War, that was a meetinghouse, a school, and an employment center. While a fair share of associations existed for Negro men, there were too few for women, particularly the “many green southern Negroes” newly arriving on New York’s docks. The Colored Mission was known particularly for its work, in conjunction with other community-based charities, on problems unique to industrious Negro women, who, in their naïveté, were vulnerable to all manner of exploitation. The Colored Mission strove to get them proper lodgings and work.26

Lloyd Jr.’s mother was the cleaning woman at the Mission, so he had practically grown up there and became an unusually young member of its staff. Ella was one of the Mission’s social workers. She was three years Lloyd’s senior, but his gentle nature, his studiousness, and his ambition inflated him with maturity. The affable young Lloyd Jr., “whom every one was attracted to,” was bookish but athletic. He was musically gifted as well, with a beautiful voice that he likely inherited from his mother, who in earlier days had had a dalliance in the theater. His father, Lloyd Sr., was the head hall man at the Lotos Club, one of the city’s most venerable Gilded Age gentlemen’s clubs, founded in 1870, on Fifth Avenue at 21st Street; member Mark Twain had wittily dubbed it the “Ace of Clubs.”

When the Mission formed a boys’ club, Lloyd Jr. joined and was soon its director, meeting with the boys six nights a week, when he was just nineteen. “It was a great task for so young a lad,” Ovington wrote. “Some of the club members were older than he, they all knew him, and there was the danger that they might not submit to his authority as readily as to that of a stranger. But this, instead of proving a hindrance, was a help. The boys knew him, and therefore they trusted him.” In charge of thirty boys, he taught them music and organized five of them into a skillful singing quintet; he also coached them in basketball in the Mission’s yard. At seventeen, carrying over his passion for organizing from the Mission, Lloyd had joined the Bethel AME Church, where he and Ella together became diligent members of the community.

In 1905 the Cofers were living in the Tenderloin—in the household of Williams and Ella’s parents—at 117 West 30th Street. Lloyd Jr.’s ambitious labors were exacting a toll on his health that no one had begun to fathom. Employed as a stenographer for a neighborhood tobacco firm, he was reportedly “so anxious to advance himself that he overworked.” In mid-August 1906, he fell ill with typhoid. Now, stressed even more about “the little round bundle of a third Lloyd Cofer at home,” he surrendered to others’ urgings to go to Bellevue Hospital for the best care. But shortly after midnight on August 29, following a two-week bedrest, Cofer awakened in a delirium. The ward’s nurse was absent when he dove out the window to his death in the yard thirty feet below. “That such a thing should have happened in the hospital is a terrible indictment upon its management,” Ovington wrote mournfully. And perhaps upon a society where a man’s wholesome striving to excel should usher him to the breaking point.

Williams’s parents had at some point bought a family plot at the Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn, where their son-in-law appears to have been the first laid to rest. Unfortunately, another family member would be buried there less than two years later. In the spring of 1908, James’s eldest brother, John Wesley Jr., who had miraculously rebounded before a coroner’s mortal pronouncement in 1900, died at the same West 30th Street apartment, from tuberculosis.27

By the end of December 1906, James Williams and his co-workers had adjusted, along with Grand Central’s constant bustle of travelers, to the temporary terminal on Lexington Avenue. The following summer he witnessed the New York Central line switch all its trains to electric operation, then likewise the New Haven line a year later. In January 1909, as the last steam engine was removed from Grand Central, a golden (if troubled) age of America’s national rail system slowly receded like a fog.28 But nostalgia evaporated quickly for Williams in the face of new prospects. Sometime between 1908 and 1909, C. L. Bardo, superintendent of Grand Central Terminal, was mulling over the necessary interplay between train passengers and station crew. He zeroed in on the station porters, the kinetic flow of their crimson hats—bobbing, idling, gathering, dispersing, appearing, vanishing—among the constant throng of travelers in the station. Bardo determined that, as more would now need to be hired, their duties ought to be regulated and supervised.

In April or early May 1909, Superintendent Bardo promoted Williams chief attendant of the Red Caps.29 Despite the official word ATTENDANT on their uniform caps, “Red Cap” was their bonafide appellation. The term would classify their station assignments, pay, wages, locker room designations, and recognition by the traveling public.

That black New Yorkers felt a collective investment in Williams’s achievement was little surprise, for it counted as a significant stride toward racial uplift. Even John E. Robinson—an up-and-coming journalist who wrote the first full profile of Williams for the August 1909 issue of Colored American magazine—might have had some personal motive in promoting his subject: Robinson and Williams were brother officers in the Manhattan Lodge of Elks. Robinson had a faster connection still: the fledgling newsman worked under Chief Williams, his profile subject, at Grand Central Terminal. Robinson, who would soon become an editor at the New York Amsterdam News, was one of the city’s many black men who worked as Red Caps while aiming for other professions.

Inevitably, Robinson’s profile of Grand Central’s auspicious race man thrust Chief Williams into public view. The article, which featured Williams’s handsome Sarony portrait, cropped in oval cameo, surely stoked a proprietary fondness among black subscribers, and the interest of its fewer, but mindful, white readers. “Mr. Williams holds one of the most responsible positions—as little as it is known—at this great railway station, that of chief of the Red Cap attendants,” Robinson wrote. “When C. L. Bardo, superintendent of the Grand Central Terminal, promoted Mr. Williams to the position it is said the he did so largely because the young man had for seven years shown himself to be an honest, faithful and trustworthy employee, one who had the ability to succeed where rare skill, devotion and diplomacy are prime requisites.”

Having had ample occasion to hone his interpersonal and managerial skills at Thorley’s, it came as no surprise that Williams had fine-tuned the Red Caps’ working performance: “The men are considered by the traveling public to be the best attired and disciplined body of men to be found at any railway terminal.” And Red Caps demonstrated their esteem for their new boss. If Williams ever worried that any of the Red Caps might begrudge him his promotion, attendants from the night division disabused him of such concern, as they “presented him with a fine traveling bag made by one of the best manufacturers of leather goods in the city.” The day men celebrated his titled promotion likewise.30

On Saturday, August 7, 1909, brimming with his newfound celebrity, the Chief and Lucy left Grand Central with their friends Jesse and Florence Battle for Michigan. The friends then lived across from each other on West 136th Street, the Williamses at number 44, the Battles at number 27. Williams and Battle were both Manhattan Lodge delegates to the Elks’ annual Grand Lodge session taking place from August 9 to 12 in Detroit. While the trip was only about a week long, it was no doubt an anxious one for Lucy, thinking constantly about the kids at home. There were plenty of family members to supervise them, but four-year-old Dorothy, the youngest, needed the most attention. James and Lucy got back from the Detroit convention by mid-month, nevertheless their return coincided with a tragedy inside Grand Central Station.

Early on the morning of August 17, a thirty-year-old Red Cap, Louis H. Blackwell, had a fatal accident. The porter was towing a heavily stacked baggage truck along a train platform, when an incoming suburban train clipped some of the trunks. The baggage truck overturned, sending Blackwell to his death on the tracks. Reverend Brooks presided over the funeral the following Saturday at St. Mark’s Methodist Episcopal Church. Chief Williams selected the pall bearers, who included his friend Lloyd Jones and other Red Cap section officers. Although some years later, after litigation, the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad Company would pay a $500 judgment to Blackwell’s family, Williams understood how unprepared his men were for sudden misfortunes.31

That harsh lesson became even more painfully clear a month later, when personal tragedy consumed the Williams home: On September 24, James and Lucy’s four-year-old daughter Dorothy died. Sick for over a year, she had finally been confined for a couple of weeks in the Hospital for Ruptured and Crippled Children—which was next door to Grand Central Station—where she succumbed to “tuberculous meningitis and hip disease.”32 Dorothy’s funeral took place in the family’s apartment two days after she died. Her baby photo, which James and Lucy had had taken four years earlier, downtown at the Sol. Young Studio (next door to Gilsey House on 29th Street), now haunted the parlor. The intimate service was presided over by the Rev. E. G. Clifton of St. David’s Protestant Episcopal Church, where Lucy used to take little Dorothy to Sabbath School, in the Morrisania section of the Bronx. The church’s location, near the New York and Harlem Railroad lines, accounted for its congregation’s considerable number of Pullman porters and Grand Central Red Caps, who now formed the mournful gathering. Williams’s old boss Thorley likely provided many of the overflowing floral tributes that followed the little girl’s funeral cortege to the Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn.

Injury, illness, and death that found Williams both in and out of the workplace: his eldest brother’s death the previous year (John Wesley Jr. had survived being stabbed in 1900), his baby girl’s death, and his man Blackwell’s fatal tragedy in the station fueled his call to action toward improving the Red Caps’ working conditions. On the evening of September 14, a week before Dorothy died, Williams had summoned his men to the True Reformers’ Hall—another church, a block east of St. Mark’s, at 153 West 53rd Street—where the gathering organized “a beneficial and benevolent society, to be composed exclusively of Grand Central employees.”

The twofold mission of the Attendants’ Beneficial Association of Grand Central Terminal was to promote fellowship among Red Caps and to provide aid in case of sickness, injury, or death to their uninsured, and unsalaried, members who depended on tips. The men elected Williams president, and Battle (then studying for the police exam) as sergeant-at-arms. Williams no doubt modeled it after similar mutual aid, or so-called “sick societies,” that black citizens were familiar with.33 Even without the advantage of organizational records, the present writer can see its importance: fifteen years later, on November 18, 1924, the song team of Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake would dedicate a performance of Chocolate Dandies—their Broadway musical hit, which launched the comedic dancer Josephine Baker—as a benefit for the Red Caps Sick Fund of both Grand Central and Penn stations.34

The attendants’ resolved solidarity coincided with a new sense of permanence around their common workplace: the New York Central announced that its executive offices, traffic operations departments for both freight and passengers, legal and financial bureaus, “have removed to the new Grand Central Terminal,” even as construction was still under way.35 Just as Grand Central Station was setting new standards for rail travel, Williams was instilling in his Red Caps a new sense of purpose and self-confidence—not to mention an essential sense of community empowerment and self-reliance in the face of occupational disfranchisement. In addition, he was effectively shaping a Negro workforce that would become an exemplar of grassroots enterprise, lobbying, and philanthropy.