CHAPTER 5

Harlem Exodus to the Bronx and to the Sea

There has been quite an exodus from that neighborhood to the Bronx and Williamsbridge.

—NEW YORK AGE, 1908

By summer of 1910, the Williamses’ grief over little Dorothy’s death had somewhat waned with the needs of their four other children—Wesley, Gertrude, Leroy, and Pierre. Wesley, the eldest, played a particular role in lifting the household’s spirits. A few weeks shy of his thirteenth birthday, he distinguished himself on behalf of his school by bringing home “one of the medals in the Evening World athletic games.” Public School no. 89 at West 134th Street and Lenox Avenue was one of the venerable old schools from Harlem’s sleepy decades past, and Wesley’s achievement would have imbued the burgeoning black community with pride. Like any other striving community, Negro Harlem measured its prospects by the achievement and potential of its progeny. Wesley, like colored boys all across America that summer, likely imagined that prizefighter Jack Johnson’s superhuman sweat anointed his own victory as one for the Race.

During the late spring of 1910, keen anticipation over the imminent “fight of the century” had steadily swelled to a national cause célèbre. Though Johnson reigned as the World Colored Heavyweight Boxing Champion, the color line that ran through other organized sports barred him from matches sponsored by the white World Heavyweight Boxing Championship organization. As potential white opponents routinely refused the black boxer’s challenges, Johnson took a creative tack by doggedly following his worthiest white contender around the globe. On December 26, 1908, he entered a ring in Sydney, Australia, squared off against Canadian boxer Tommy Burns, and duly relieved him of the World Heavyweight Champion title. Back in the United States, Johnson’s victory over Burns unleashed the nation’s deep-seated racial tensions. Sportsmanship gave way to explicit avowals of defending white supremacy. Somewhat despairingly, white promoters coaxed a former pugilist champion out of his five-year retirement: Jim Jeffries would be America’s “great white hope” to defend the heavyweight title against the audacious black contender. Jeffries aimed to put Johnson in his place on the Fourth of July.

The historic Johnson-Jeffries fight took place in Reno, Nevada, on July 4, 1910. Obsession over its outcome was countrywide. The florist Charles Thorley—Williams’s former boss, who was also a well-known sportsman—witnessed the fight and bet $5,000 with odds on Jeffries to win. Years later the florist recalled the fight as the greatest, but most disappointing, match he ever saw. “Johnson outclassed Jeff, or rather the shadow of the once great Jeff, from the start.”1 In New York’s Times Square, a mostly white crowd of thirty thousand watched play-by-play bulletins on the Times Building as Johnson decisively won the bout. Depending on who one rooted for, the disappointment and the satisfaction were equally palpable. Up in Harlem, the Williams household was surely apprehensive of sudden mayhem—only ten years earlier whites had spontaneously attacked blacks in the city.

Johnson’s victory immediately ignited plans for feting his return to the city, and Chief Williams was thrust directly into the maelstrom of celebratory preparations. The process had been in the making since Johnson won the World Heavyweight Champion title from Burns in Sydney. Black fans in New York had been effusive in their recognition of Johnson as world boxing champion. In the spring of 1909, Colored Elks and black businessmen had offered consecutive evening events to kick off a weeklong series of receptions for the boxer. On March 30, Williams’s Manhattan Lodge had entertained Johnson at Palace Hall. Then on March 31, the reception committee chairman Barron D. Wilkins, said to be Johnson’s closest friend, spearheaded a three-dollar-per-plate dinner and reception (about $75 in 2018 currency), sponsored by many other black business leaders, at American Theater Hall. (The affair likely enabled Barron Wilkins to wire Johnson $20,000 in Reno some weeks later to bet on himself.)2 Though he held no official office, Wilkins owned Café Wilkins in the Tenderloin district, which served as Johnson’s de facto headquarters. The place’s innocuous name was perhaps a purposeful distraction from its former name, the Little Savoy, an infamous “black and tan” hotel-saloon that catered to a Tenderloin clientele of sporting men, ragtime cabaret acts, and white revelers.

Barron Wilkins and the boxer’s personal lawyer, J. Frank Wheaton, were two of the most prominent brother “antlers” in the Elks’ Manhattan Lodge. Now as Wilkins was charged with arranging the celebrations for Jack Johnson’s victorious return, his effort to engage “every sight-seeing car in the city” surely drew support from the ranks of his own lodge—support particularly from Williams, one assumes, who frequently teamed with Battle in organizing important lodge functions. Wilkins also headed up the Jack Johnson Diamond Belt Subscription Fund, a corollary committee that formed with the mission to engird the new world champion in a $25,000 gem-studded gold trophy belt. That the Chief of course knew the principals surely impressed his raptly interested son Wesley. One of them was “the colored whirlwind,” the eloquent public speaker D. E. Tobias, whose kaleidoscopic roles included publisher, economist, criminologist, psychologist, and political gadfly, who also did a fair amount of dabbling as a Tin Pan Alley music publisher (he cofounded the black-owned Gotham-Attucks Company), and theatrical press agent. Tobias also happened to live in the same building in the Tenderloin as young Wesley’s grandparents, Aunt Ella and little cousin Lloyd, and a few uncles who had yet to move up to Harlem.

The city readied itself for Jack Johnson’s arrival as the 20th Century Limited carried the champion from Chicago, like a long-burning fuse. The train was to deliver the hero to Grand Central, whose old station building had been abandoned just a few weeks before. On Monday morning, July 11, crowds descended on the station to greet Johnson’s arrival at nine-thirty. A wreck upstate of the Northern and Western Express delayed the train, but the crowd—which by most accounts numbered several thousand blacks and several hundred whites—waited resolutely for their idol with his gold-filled smile. At about a quarter past two in the afternoon, nearly five hours late, the Century finally appeared. As the train backed slowly into the station, James “Gentleman Jim” Corbett, another former heavyweight champion, “stood, grip in hand,” in the vestibule of the first car, which “slid past and nobody’s eyes followed it.” Rather, messengers from Johnson’s reception committee dashed off to alert waiting autos. The committeemen trailed a motley crowd of black and white fans as they hustled down the platform toward the train. Williams tried to bring order to the frenzied scene on the platform, where passengers stepping from the cars were at pains to get a Red Cap’s attention to take their bags—all of them bent on greeting Johnson.4

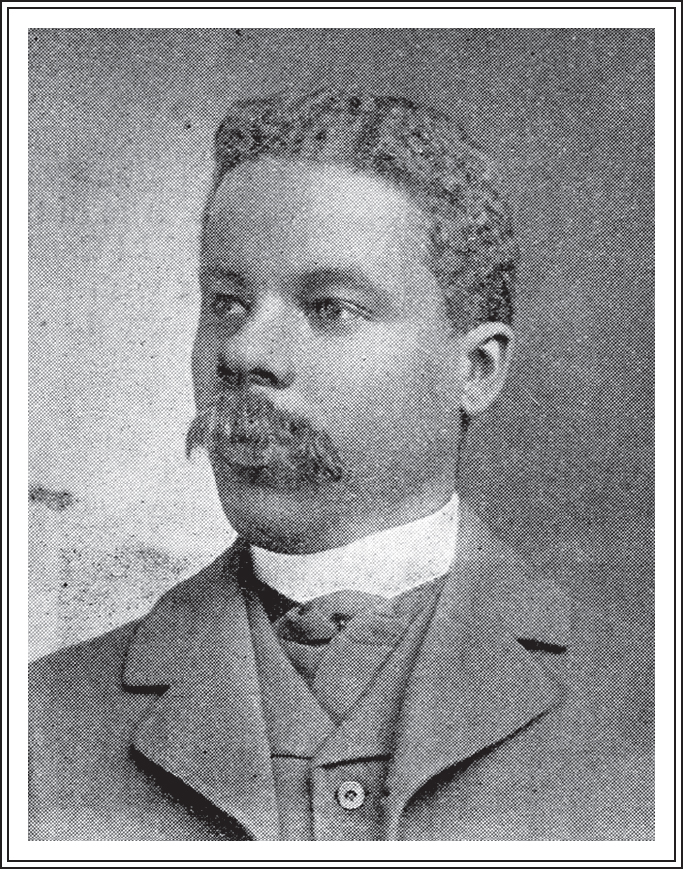

J. Frank Wheaton, formidable attorney for Manhattan Lodge no. 45 and boxer Jack Johnson, was a force behind Samuel J. Battle’s historic appointment to the New York City Police Department. Photo: Circa 1899, by Charles Alfred Zimmerman, Minnesota Historical Society.

As much of white America begrudgingly acknowledged Johnson his world title, some recalcitrant forces in white Harlem were stalwartly resistant. Only a decade into the twentieth century, the black foothold in Harlem was unambiguous, with a steady influx of black tenants, thriving new businesses, and flourishing organizations. A number of white property owners found the change irksome enough to wage a battle to determine “whether the white man will rule Harlem or the negro.”5 Yet as white property owners closed ranks, black Harlem, having a burgeoning population in its favor, stood its ground.

A pivotal voice of opposition belonged to John Goldsburgh Taylor, a sixty-two-year-old realtor who emerged as white Harlem’s self-appointed paladin. As founder and president of the Property Owners Protective Association, he raised $20,000 to bankroll the purchase of Harlem properties on the market before black buyers or agents “of ‘Little Africa,’ just east of Lenox Avenue,” might obtain them. Built for intimidation and strong-arming, the southern-born Taylor stood six feet four inches tall and weighed more than 250 pounds. His dense mustache hung from his nose like the brooms he sometimes suspended from building windows to signify his “clean sweep of negroes from the white resident districts of Harlem.” He spent the next four years confederating his like-minded white neighbors to drive back their “common enemy,” the Negro invaders who appeared poised to move westward across Lenox Avenue into West 136th Street. As Taylor stirred up fellow whites to confront their existential crisis, his campaign particularly sought to oust an explosively successful new colored saloon on the intersection’s southwest corner.6

On a Tuesday evening in November 1910, Williams’s Elk brother Leroy Wilkins had opened Café Leroy at 513 Lenox Avenue (many years later to become the site of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture). He had sold his other Harlem cabaret—the Café Astoria—to his older brother, Barron, who would give the address greater fame as the Exclusive Club. At his new place, Leroy obviously spared no expense transforming the three-story building into the city’s most modern restaurant for a colored clientele. Café Leroy was extravagant: “One of the features is the $3500 organ which can be heard throughout the building,” the Age reported, adding that in the “rathskeller”—as basement-level eating halls were still commonly called—the proprietor had installed a smaller organ.

First-night Harlem customers poured in. They pressed through the first floor to the bar, some of the men to the wine rooms. Some ascended the stairs to fill restaurant tables on the second floor; others continued yet higher to the third floor to join parties in the private dining rooms. While many exalted the swank Café Leroy as the “Colored Rector’s,” evoking one of the city’s poshest white establishments near Times Square,7 John Taylor disparaged the grand place as being frequented “exclusively by negroes or dissolute white persons.” He succeeded in convincing the court to revoke the proprietor’s saloon license, which he asserted Wilkins’s partner had forged names to obtain.8 Leroy Wilkins ultimately moved his café to Fifth Avenue and 135th Street, which was close enough to retain his devoted clientele—and also close enough to deprive Taylor of feeling comfortably smug.

Williams and other black Harlem residents might have remembered Taylor from the Tenderloin. The zealous realtor was a retired police officer, whose strapping figure was unmistakable among the rank and file of the 30th Street Station. Still burly and imposing, Taylor might have been itching to avenge Jim Jeffries’s recent loss of glory to Jack Johnson, as he now poised himself for battle. He advised white homeowners to build twenty-four-foot fences to separate their properties from those of their black neighbors. Though such outlandish industry was never realized, his organization did succeed in closing the first sale of a property “restricted against use by colored tenants for fifteen years.” The sale of the townhouse at 210 West 136th Street appeared to be the first recorded transaction on Manhattan “of property restricted against use by a particular class of tenants,” reported the Times. Insurance for the property title was contingent upon it remaining in that condition.9

Taylor’s schemes may have been more foolhardy than foolproof. One of his prolific newspaper ads boldly proclaimed, “200 WHITE FAMILIES MOVE BACK TO HARLEM,” as its cartoon of a horse-drawn moving van assured of “MORE COMING EVERY DAY.” It is true that for a time restrictive covenants effectively barred black tenants from several Harlem blocks. However, Taylor’s strategy to attract new white tenants with the promise of low rates, by special arrangement with property owners, appeared hopelessly flawed—some cosigners broke the covenants themselves. After selling her house on West 136th Street to a black buyer, one white owner reportedly declared her right to sell it “to any person she saw fit,” and dismissed the covenant as “a big joke.” Another owner, on the north side of the exclusive Astor Row block of West 130th Street, found white renters were unwilling to pay a fair rent in his brownstone, so he put out signs for “respectable negro tenants” instead. “Yes, I think I can get more from negro than from white tenants,” he said, “and I have two or three propositions under consideration.” And why would he not? An owner wanting to sell or lease property, having no white buyer at the door, was unlikely to ignore the knock of a prospective black buyer.10

By 1914 more and more white property owners had defected, and Taylor’s most recent strategy, to sue covenant breakers for damages, was made moot by his death. As Taylor lost influence in his neighborhood and his association, then lost his life, the black Harlem of Williams’s generation thrived and expanded.

Jack Johnson’s victory might have steeled the resolve of black Harlemites to resist Taylor’s relentless attempts to oust them. And their resistance may have bolstered a cultural sense of place and entrepreneurial confidence, for a considerable number of Harlem’s professional class now appeared poised to leave the neighborhood of their own volition. Without pulling up stakes entirely, a number of Williams’s friends were moving from Harlem up to the Bronx, and they encouraged him to consider doing the same.

In 1910 the Bronx neighborhood of Williamsbridge had seen the establishment of a recreational center, probably catalyzed by the commotion surrounding the Johnson-Jeffries match. The nationally segregated Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA)—whose Jim Crow “colored” branches were central to black communities around the Tenderloin and elsewhere—contributed to the growth of black Williamsbridge. In 1910 the white Williamsbridge branch of the YMCA leased out a disused building to the Williamsbridge Colored Men’s Association (WCMA), or Wicoma. The Wicoma reclaimed the castoff space at 706 East 215th Street near White Plains Avenue with gusto and carried out the similar physical, recreational and spiritual mission of the white facility. A local ladies’ auxiliary furnished the club’s well-equipped gymnasium, which opened daily at hours staggered for boys and girls. The basketball court was evidently popular, as its two basketball teams showcased promising athletes the first winter after opening.11 There were also bowling alleys, a pool table, and showers. The white Williamsbridge branch Y’s physical director and gym leader conducted classes at the Wicoma. A glee club and a debating club were organized. The black Wicoma in Williamsbridge—which operated out of the white YMCA’s old rooms until 1918—predated Harlem’s 135th Street Y by several years.12

The impressive board of managers elected to the Wicoma expressed their commitment to “uplifting the young men of the vicinity” with the new facility. Several, including Jacob Charles Canty and Sandy Jones, were noted “property owners of no small extent.” Jones now worked with Nail and Parker, Harlem’s best-known real estate firm; he had known Williams since both lived on West 134th Street, and both were fraternal officers of Manhattan Lodge no. 45, working on the arrangements committee for big Elks events. Jones, who knew James’s family, most likely encouraged the Chief to seriously think about moving to the “Bridge.”13

In March 1912, Chief Williams was already comfortably settled in Harlem. A move to Williamsbridge, about six miles north, seemed unnecessary. But some of Williams’s friends had moved there, and he knew the realtors Nail and Parker personally, so he looked over the ad that his friends put before him. The house was in the north-central section of the Bronx: “1st floor of 6 rooms and bath, steam heat. Rent $23.”14 The monthly rent was comparable to rents in Harlem.

Prominent colored folk had been venturing to Williamsbridge for more than a decade—most notably Jacob Charles Canty, a southerner who had come north for a medical degree. In 1886 the limited prospects in Negro communities induced him to give up his professional ambitions and become a railroad porter. He was assigned to the original crew of the New York Central’s Empire State Express. For forty years he rode back and forth between New York and Buffalo, totaling more than six million miles by his retirement in 1926. “Doc,” as his Pullman co-workers referred to him, had bought several pieces of Bronx property in Williamsbridge. “Even before the first influx of colored people had started toward the Harlem River from the Tenderloin district,” the Age reported, “he was advocating that section of the city to his friends as the coming residential section.”15 One Martha Jefferson, wife of a railroad porter who had run a colored lodging house on West 134th Street, was happy to quit Harlem for quiet Williamsbridge. “There has been quite an exodus from that neighborhood to the Bronx and Williamsbridge,” the paper quipped. “Upon closer acquaintance that latter place don’t seem to be as far removed from civilization as was formerly believed by some.”16

Indeed, by 1912 Williamsbridge was a buoyant community, plugged into the circuitry of black Manhattan. St. Mark’s Methodist Episcopal Church, which Williams knew from West 53rd Street, had just opened a mission church there. It was farther from Williams’s workplace, but the direct rail line between Grand Central Terminal and the Williamsbridge station along the Bronx River would make the commute faster than by subway. And annual company passes permitted workers to ride the line for free. As improving transit had induced other friends to move from Harlem’s tenements to greener suburbs, Williams soon succumbed and moved his family to 823 East 223rd Street in Williamsbridge. The Williamses were not long without their friends, as the Lloyd Joneses (no known relation to Sandy Jones), the Battles, and others joined the influx of middle-class Harlemites. Harlem’s cultural annexation of Williamsbridge as a “race” suburb was apparent by the summer of 1913, when the New York Tribune reported that “a new colored settlement has sprung up in The Bronx in the last six months,” with a population of five thousand.17

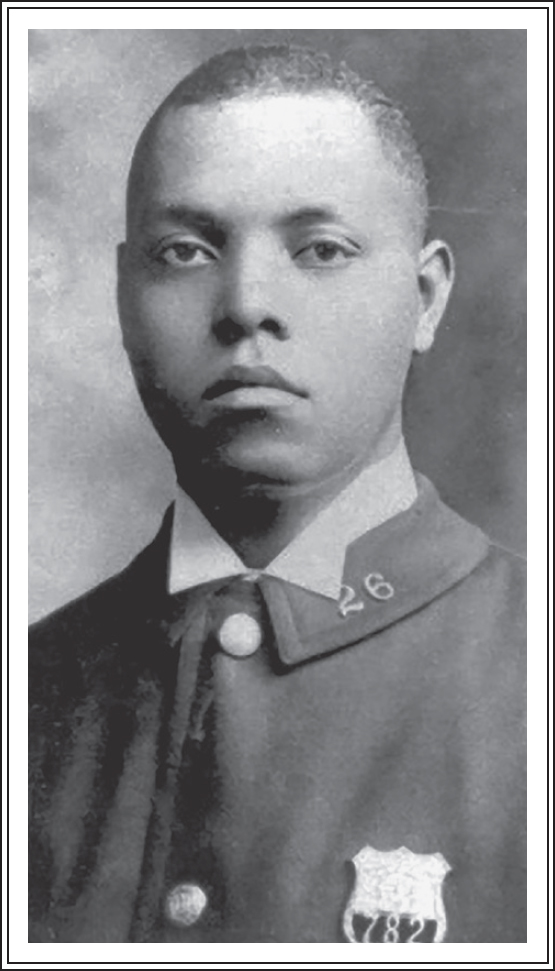

While assistant Chief Red Cap under Williams, Jesse Battle prepared for the exam that made him New York City’s first black police officer in 1911. New York Police Department Museum.

That summer a group of thirteen black teenagers from Williamsbridge clacked across the wooden floorboards of a photographer’s studio. Wearing smart, colorful uniforms, with cleated shoes, banded leggings, knickers, piped and embroidered jerseys, and brimmed red baseball caps, they constituted the Grand Central Red Caps baseball team. In the photograph, two additional young men pose with the team in suits and straw boater hats, likely athletic managers from the Wicoma. These young men were sons of Grand Central porters (and maybe a few worked as porters themselves). Chief Williams’s sixteen-year-old son Wesley sits on the floor beside a tripod of crossed bats. Wesley was developing into an all-around athlete in Williamsbridge, a fact that surely informed the gusto with which Chief Williams approached his leadership at Grand Central. Baseball and other athletics clearly had the potential to strengthen the fraternity of porters.

Lucy and James’s teenage daughter Gertrude also thrived in Williamsbridge. In February 1914, it was probably she who placed an ad from the family’s address: “Colored Girl wishes position at housework; good references.”18 She certainly had references. By the summer of 1918 Gertrude had graduated from high school and, recently appointed a postal clerk, was cited among “the young Race women of Williams Bridge . . . taking advantage of the opportunities now afforded by the present war” as the nation was fighting in Europe.19

For his own part, James Williams appears to have joined the Butler Memorial Methodist Episcopal Church, at 719 East 223rd Street, near White Plains Road. Established by St. Mark’s in 1912, it was one of the community’s three black churches. On one Friday evening in June 1916, Williams was floor manager for an event at the Masonic Hall at East 216th Street and White Plains Avenue to benefit the church’s Lyceum (which, organized in 1883, identified itself as “the oldest literary society in the State of New York”). The amateur players had a full house for their presentation of two one-act plays (one being Bargain Day, a popular vaudeville farce by Mary H. Flanner), followed by an evening of dancing.20

But on November 6, 1915, Butler Memorial’s doors opened for the most important event in the Williamses’s lives: Wesley Augustus Williams married Margaret Russell Ford, his sweetheart from New Rochelle. Like his father, Wesley was a Red Cap, though at Penn Station; and similarly as well, he was eighteen as he stood at the altar. The Chief’s eldest daughter Gertrude and his own older brother Charles stood as witnesses,21 as other family members and close friends crowded the little frame church. The Chief and Lucy Williams, perhaps taking turns holding their baby daughter Kay, beamed as their firstborn, Wesley, entered married life.

On a mid-August evening in 1913, Chief Williams hosted “a Red Caps stag” dinner in honor of Jesse Battle, who was celebrating his second anniversary as New York City’s first Negro policeman. Williams’s own sense of personal achievement might have equaled that of his guest of honor: he had drawn Jesse from the ranks of his luggage porters, promoted him to his assistant chief, and encouraged him to study at night for the civil service examination. For this high celebration, whose details are unknown, Williams had chosen the Hotel Lincoln in Arverne-by-the-Sea, a swank colored resort on the city’s Rockaway shoreline.22 The sea retreat’s conspicuous black visitation had coincided with Harlem’s wave of black settlement.

Almost a decade earlier, on the sunny Sunday afternoon of June 26, 1904, several white residents of Arverne-by-the-Sea strained to look over two six-foot-high board fences on the boardwalk. Employees of William Kemble’s Halcyon Casino Company were holding a pleasant outing with about “a dozen or more negroes sitting in willow rocking chairs” and enjoying basket lunches and ice cream. The uncommon scene so perturbed the white residents at the fence that some hurled racial slurs at the guests. Others “took snapshots of the negroes as they were being served” to later incriminate their host.

Kemble had apparently been upsetting his neighbors for some time, as he intended to build an amusement park and casino on the site. The attraction was certain to mar the residents’ sea vista and disturb their tranquility, so Arvernites had secured a court injunction to forestall construction. Kemble responded to this preemptive strike by setting up a number of small shanties on his casino property, where several local passersby heard—coming from behind the tall plank barricade—the distinct voices of black people “enjoying themselves with banjos, rag-time, and plantation melodies.” Many thought Kemble’s retaliation played upon his neighbors’ dread—not of a proposed carousel but of Negroes.23

White property owners organized themselves into the Arverneby-the-Sea Association, which resolved to “starve out” a black realtor’s expensive new boardinghouse elsewhere for wealthy Negro patrons, by imposing a covenant warning “storekeepers who sell to the negroes are to be boycotted.”24 But fashionable colored folks were undeterred. In fact, the next summer, on July 10, 1906, a particular function might have made the seaside locale still more enticing: “Booker T. Washington, the famous educator, entertained a large audience . . . in the Ocean Casino with a discussion on the race problem.” Perhaps celebrity itself, that all-American obsession, fueled Arverne’s appeal to black social circles as a convenient getaway.25

In the summer of 1908, Williams likely heard about the opening of a new hotel at Arverne-by-the-Sea. The Hotel Lincoln was the latest seaside resort for colored patrons to dot Rockaway Peninsula’s communities of Seaside, Rockaway Beach, and Hammels. The Lincoln’s close proximity to the city made it a choice refuge for middle-class and affluent blacks looking for a reputable getaway. Indeed, at the end of July, the overflow of nearly a hundred guests from Manhattan, Brooklyn, and New Jersey necessitated turning many away. But those who found accommodations for the weekend enjoyed an afternoon auto outing, reveled at a “hop” in the pavilion, took advantage of the excellent bathing, and delighted in an impromptu concert arranged by the noted newspaper correspondent Cleveland “C. G.” Allen, whose investigation of the U.S. Navy’s discrimination against its enlisted Negro seamen would catapult him to national prominence four years later.

Whether Williams was there that weekend is unknown, but he knew from the papers and the talk that it was quite a celebration. If Wiley H. Collins and Vincent Taylor, the Hotel Lincoln’s managers, had the regrettable task of turning away guests, their regret was mitigated by the guilty pleasure of success. They reserved a special table in the main dining room for Mme. May Belle Becks, a modiste. A few months earlier she had opened a special school in Manhattan: the Mme. J. H. Becks School of Dressmaking, Designing, Cutting, and Fitting, and it was gaining much attention. William Jay Schieffelin, a noted white philanthropist who chaired the New York Committee for Improving the Industrial Condition of Negroes, publicly asked “those who can [to] give work to colored dressmakers and milliners.”26 Madame Becks’s dressmaking school was securing her a redoubtable stature as “the foremost colored designer in this country.”27

In the spring of 1910, numerous black periodicals advertised the resort at 22–24 Lincoln Avenue. Williams saw the photo of a squarish three-story, wood-framed manse, the central door recessed in a porticoed porch. The Lincoln, only a block from the beach, offered such seasonal diversions as cruising, boating, bathing, and fishing. It was easily reached from the city by taking any Rockaway Beach train to Hammels Station. A succession of at least three proprietors—Emma I. Dorsey, F. M. Allison, and C. A. Breckenridge—were all women. During the Fourth of July weekend of 1913, James Van Der Zee—who would earn eternal renown as a photographer—was an accomplished violinist and pianist when he checked in at the Lincoln with his wife Kate Brown, as leader of the Harlem Orchestra.28 Bandleader James Reese Europe and his wife Willie Angrom Starke checked in exactly two years later; and businessman John W. Rose—owner of Harlem’s first restaurant chain, Rose’s Dairy Lunch System—relaxed there with his wife Theresa in July 1916.

In mid-July 1914, Chief Williams spent a weekend at the Hotel Lincoln. His name appeared first on the hotel’s registry of notable patrons, which must have tickled him—it preceded that of an international star, Bert Williams. The two Williamses were unrelated, but they shared something: James Williams was Chief of Grand Central’s Red Caps, while Bert Williams played a Grand Central Red Cap in Ziegfeld Follies of 1911. Bert Williams’s legendary interpretation of the Red Cap character had convinced Florenz Ziegfeld himself to offer a three-year contract to the black comedian.

The convenience of Arverne’s Hotel Lincoln did not deter the Chief and other black New Yorkers from traveling farther afield for beach relaxation. Throughout the late nineteenth century, the railroads facilitated the flow of New Yorkers to summer in the seaside resorts of New Jersey. Asbury Park (named for Francis Asbury, the father of American Methodism) was founded in 1874 as a Protestant temperance resort but grew in a decade to become an intemperate pleasure ground of 15,000 permanent residents, some 2,000 of them black. The town flourished as a leisure campus of hotels, music pavilions, and a boardwalk punctuated with flowerbeds, piers, and fanciful bathhouses. As affluent whites flocked to Asbury Park’s myriad posh establishments—about “200 hotels, the majority of them with colored waiters”—proprietors tried to dissuade, then to restrict, the use of beach facilities by blacks, be they local workers on leisure time or those arriving on seaside excursions. A number of black clergy, like the Rev. Andrew J. Chambers, an influential AME Church pastor, expressed outrage about the proposed color line: “A man with a black skin is not a menace to the prosperity of the place.” Of course, the white resort economy of Asbury Park was dependent on hundreds of black service staff: the hotels employed two-thirds of the town’s black population.29

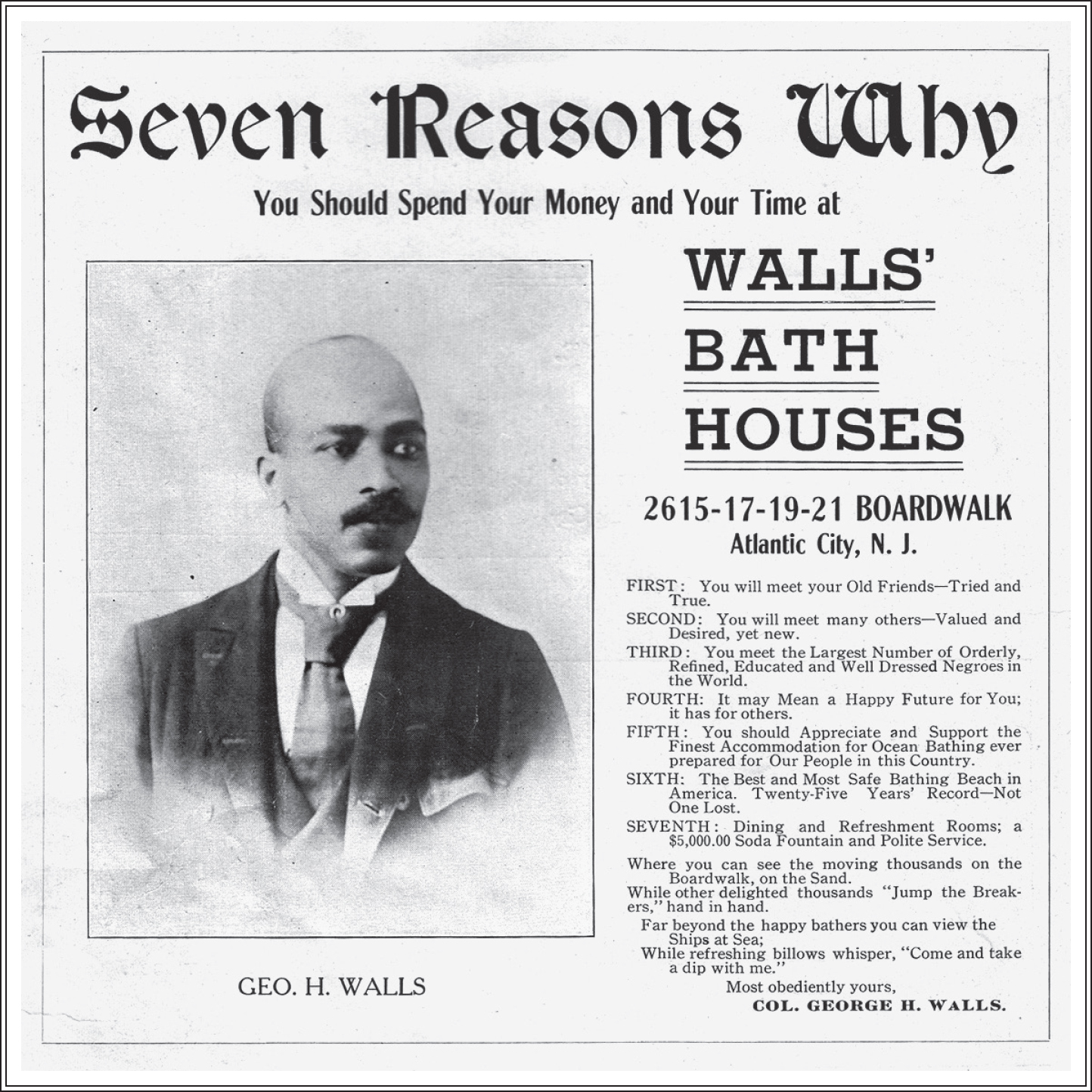

In fact, Williams was a patron of a number of black entrepreneurs who ensured the prosperity of Atlantic City, the foremost “Mecca of pleasure” of America’s leisure circuit, founded in 1854. For some thirty years, until white businesses pressured him off in 1925, entrepreneur George H. Walls, a former hotel waiter, ran the only black business on Atlantic City’s famous seven-mile Boardwalk: Walls’ Bath Houses. Numerous other bathhouses on and off the Boardwalk welcomed white hotel guests and beachgoers, but Walls’s was the only one for blacks. Located on a four-lot strip at the foot of Texas Avenue that had once demarcated “the extreme end of the inhabited section of the old ramshackle promenade,” it quickly became an attraction. In the mornings, the so-called “400” of influential black society—like violinist Joseph H. Douglass and poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, who toured together—arrived at Walls’s, eager to take the waters. Then in the late afternoons, hotel workers off their shifts came to bathe in turn. Passing the stretch of hotel beaches, black beachgoers concentrated in the few-block area from Walls’s, at Texas Avenue, to Missouri Avenue beyond. Until 1906, when a racial segregation policy was set, there was no law to prevent blacks from bathing there. And the shore in front of Walls’s—like any promenade where one went to see and be seen—offered blacks the most vibrant sense of community.30

A 1913 advertisement for George H. Walls’s four-lots-wide bath houses, the only black-run business on Atlantic City’s seven-mile Boardwalk for three decades until 1925. Author’s collection.

By the 1910s, George Walls was a preeminent figure in Atlantic City’s flourishing community of black businesses, social centers, and fraternal organizations. He increased his posh facilities with novel “shower baths” to accommodate “up to 500 bathers at one time.” Here black visitors came to rent bathing wear, lounge under a shady pavilion, and feel at home. In the summer of 1909, Walls had augmented his bathhouse’s comforts by adding full-service dining and refreshment rooms featuring a $5,000 soda fountain.31

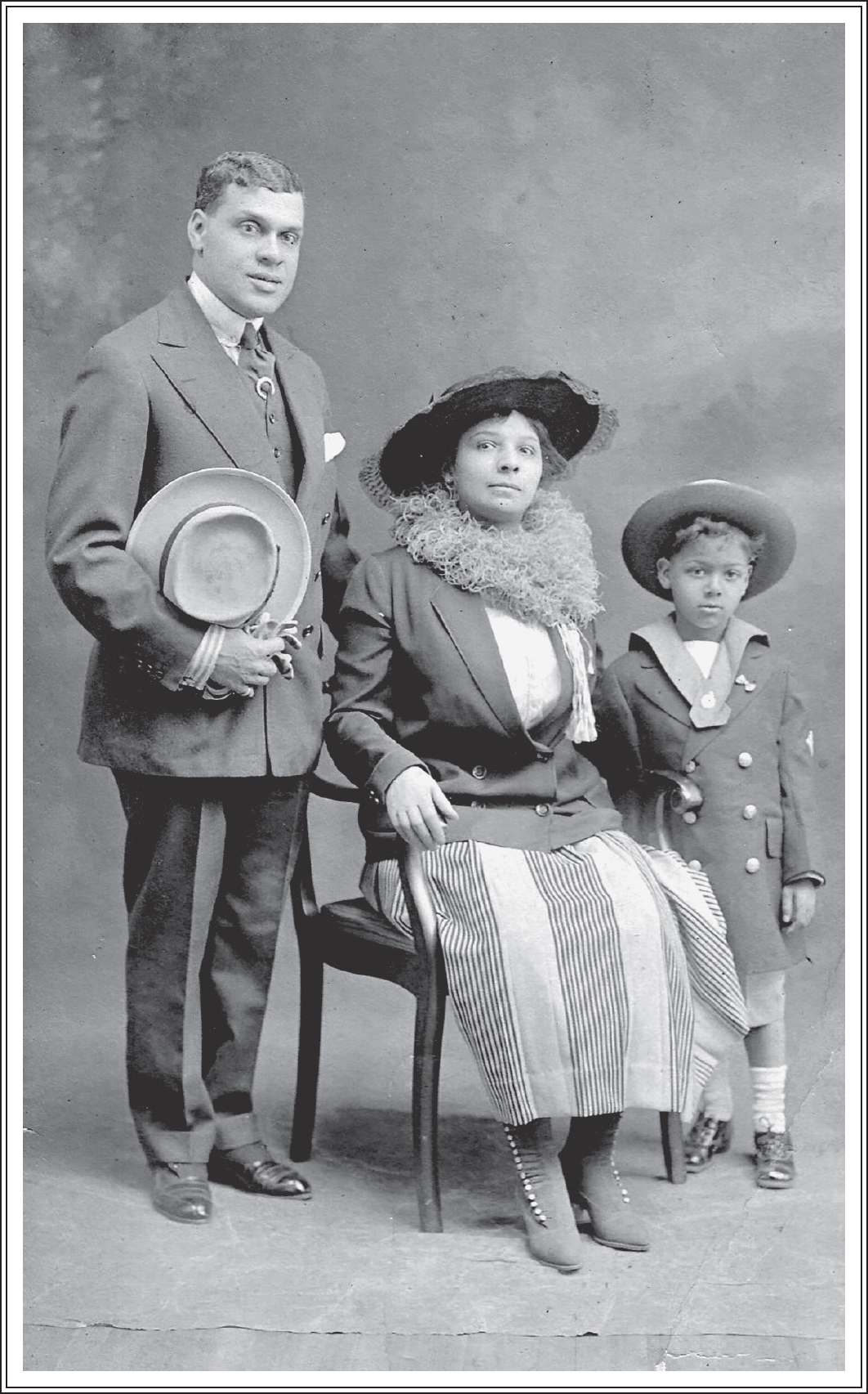

In 1916, James and Lucy Williams and their son, Pierre, posed for a photo postcard in Atlantic City. Charles Ford Williams Family Collection.

James Williams frequently brought his family to Atlantic City, when the briny sands that rolled down from Walls’s to the surf were the center of colored attraction. An advertisement for Walls’s read:

Where you can see the moving thousands on the Boardwalk, on the Sand.

While other delighted thousands “Jump the Breakers,” hand in hand.

Far beyond the happy bathers you can view the Ships at Sea;

While refreshing billows whisper, “Come and take a dip with me.”

—COL. GEORGE H. WALLS, PROPRIETOR, WALLS’ BATH HOUSES, ATLANTIC CITY32

At the end of August 1916, James, Lucy, and their son Pierre went down to Atlantic City with their Williamsbridge neighbors Sandy and Mary Jones, who had been friends since West 134th Street in Harlem. They all stayed at Lipscomb Cottage at 1632 Arctic Avenue, whose owners, Mr. and Mrs. C. D. Lipscomb, were familiar in Williamsbridge black society. The Lipscombs’ modern amenities and year-round service made it the town’s principal colored hotel. C. D. Lipscomb and his businessman colleague Walls were both officers of New Jersey’s Grand Lodge of the Knights of Pythias fraternal order. The ad for the inn featured a cameo photo of the round-faced, mustached namesake, but the fine print read “Mrs. C. D. Lipscomb, Prop.” The three Williamses stopped in a boardwalk shop to pose for a souvenir photo.

And Williams was also discovering welcome getaways even much farther beyond the city. George H. Daniels’s Four-Track Series promoted the delights of nature awaiting travelers along the New York Central’s lake routes through the Adirondack Mountains, promising, “if you visit this region once, you will go there again.”33 The Chief was privileged to do the tourists one better: for about twenty-five years, between 1910 and 1935, he took an annual fishing vacation: as the guest of Edward C. Smith, a former governor of Vermont. at Camp Madawaska, the governor’s lakeside hunting lodge in the Canadian woods.34