CHAPTER 6

War at Home and Abroad

“It’s quite wonderful, isn’t it?” I continued. “A city in itself. What did it cost? And if all the red caps were laid end on end, how far would they reach?”

—PARKHURST WHITNEY, 19161

As Grand Central Terminal took shape, New Yorkers grew rapturous. For ten years they had watched in awe as skyscrapers spiked in the city—the Singer Building (1908), the Metropolitan Life Building (1910), and the Woolworth Building (1913), and other iconic towers.2 The railroad terminal would be lower and stouter, but maybe as an inherently public premises, it loomed more personally than others. By 1911, the feat of engineering that was creating a new station on the old one’s site impressed one observer as “a project that requires more of God than of man to accomplish.”3

Williams probably felt less inclined to marvel. The terminal’s construction—the sheer, measured magnitude of it—certainly inspired contemplative wonder, but its grand incompletion made it the irresistible stuff of parody, which might not put him in the best light. Just a few blocks west, Ziegfeld Follies of 1911 was cinching Bert Williams’s reputation as a Broadway star by lampooning the terminal’s epic building-in-progress state. The legendary Negro entertainer “appeared as a ‘red cap’ to pilot an English tourist” to his New Rochelle train—a rope tethering the pair, each to each, like alpinists—by traversing the bare steel rafters of the rising terminal. In typical low comedy fashion, the wary white traveler and his black porter guide ultimately plummeted, one after the other, into the void of the building’s works—to convulsions of side-splitting audience laughter.4 Chief Williams could ill afford such burlesque missteps. As the new terminal at last prepared to open, he and his men were in the crosshairs of ineluctable scrutiny and unflattering slapstick comparisons. They were now the personification of its completion, and they must be perfect.

As the four opaline clock faces struck midnight on February 2, 1913, Chief Williams, a red carnation in his lapel, inspected his army of Red Caps in formation one last time. They numbered about 150 men of varying brown complexions, all comprising a uniform body by their identical crimson hats. Their natty uniforms bade good riddance to the days of motley so-called “public porters” who haunted the outside curbs; they stood poised to represent the new station’s exalted expectations. The doors to the new terminal were thrown open. Many local travelers ignored the railroad’s promotional assurances that the station was simplicity itself and instead “placed themselves in the hands of attendants who knew every angle.”5 Indeed, many appeared to seek out members of the Chief’s amicable crew, as if they were playing an amusing connect-the-dots game with the dart and dash of the men’s red caps.

In Ziegfeld Follies of 1911, black entertainer Bert Williams uproariously parodied a Red Cap at the new Grand Central Terminal under construction, informing Chief Williams’s determination to keep his Red Caps ever on point in the traveling public’s eye. Schomburg/NYPL.

A central information booth anchored the main concourse, but Chief Williams’s men were the terminal’s most recognizable agents in public view. By dint of their uniform clothing and their general dispersion, Red Caps had considerable authority in the eyes of visitors, at least enough to ask a question. Throngs of sightseers flocked to Grand Central not to go anywhere but to see the spectacular new station for themselves. These “railbirds” lingered endlessly up on the mezzanine gallery gazing at the main attraction, the cerulean blue “sky ceiling” that canopied the main concourse. The marble floor was visible only fleetingly through the sea of people. The Chief and his men navigated through the shoulder taps and called-out questions. “Every attendant was a walking Baedeker,” someone observed. “He had to testify hundreds of times as to the number of stars in the sky above the main concourse, as he did to most of the other unusual features of the station.”6

Not knowing Chief Williams’s relationship to William C. Brown, president of the New York Central, it’s hard to judge if seeing him on the congested concourse made him anxious. Few other railroad folks would have recognized Brown, weaving nonchalantly through the throngs. The conspicuous Red Caps were fielding a barrage of visitors’ questions, comments, and suggestions, while Brown was circulating, pausing now and then to listen unobtrusively. Williams knew that the president’s dissatisfaction with his men’s performance could be baleful. And opening day was a performance to be sure, an unusually exhausting one. One attendant tallied all the questions people asked him; he figured 310. What’s the architect’s name? What kind of marble is that? How does the electricity system work? Those figures painted on the ceiling—what do they mean? When a question about tracks in the upper express level tripped up one unlucky Red Cap, Brown, who was within earshot, stepped in to provide the answer. Brown appeared to be pleased at the opening, a report the next day noted, so Williams no doubt exhaled.7

Although the uniformed porters constituted part of the new Grand Central Terminal’s official “staff,” they were barely salaried and subsisted basically on tips. Nevertheless, the Red Caps recognized they had a position of advantage, that it was a linchpin of opportunity in a time of racial work barriers. No sooner had the new station opened than Williams’s men proactively organized business and leisure pursuits, sometimes in conjunction with other stations. His close Grand Central friend Lloyd Jones, a community activist who years earlier cofounded the Manhattanville Colored Republican Club, was an officer of the Amalgamated Railroad Employees Association, which the Pennsylvania Station Red Caps had founded two years before. While less a labor union than a traditional mutual aid society, the Penn’s Amalgamated aimed—beyond just relieving members with financial troubles—toward acting as an organizational stakeholder for their business ventures. The association not only expanded its membership to include fellow Red Caps from Grand Central, it also diversified its ranks with Harlem businessmen like the saloonkeeping brothers Barron and Leroy Wilkins. Even more ambitiously, it envisioned a countrywide network of headquarters that would serve both as social centers and as training schools for its members, whose New York base drew from both Grand Central and Penn stations. To that end, the Amalgamated leased a brownstone townhouse at 447 Lenox Avenue near 132nd Street. The New York Age described the Red Caps social club as a “commodious and up-to-date headquarters” that provided members with a restaurant “conducted on a first-class basis, and sleeping apartments, with all conveniences.” The premises were also fitted with “reading rooms, pool room, writing rooms and parlors.”8

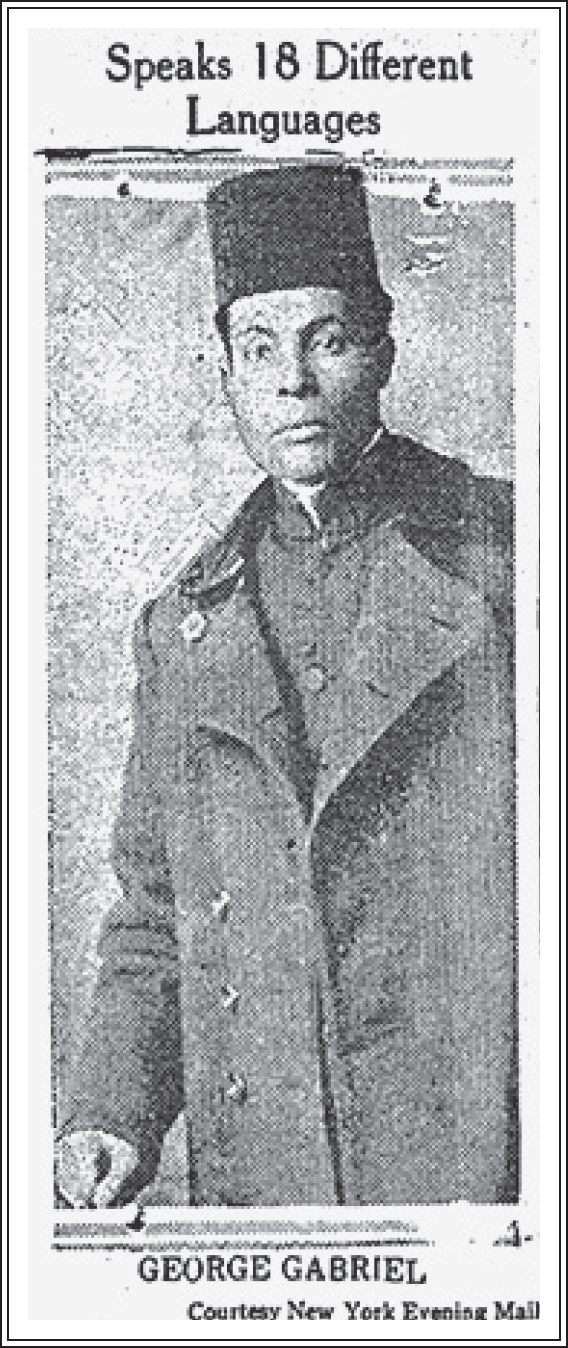

While many of the Red Caps had known each other before, or through mutual connections, neither Chief Williams, nor any of his men at Grand Central Terminal, had likely ever met an Abyssinian. The Abyssinian was their own Oualdo Gorghis, the given name of the Red Cap they knew as George Gabriel—though to the traveling public he was simply Red Cap no. 20. Born on April 26, 1888, in Addis Ababa, he immigrated to the United States on January 14, 1913, in time for Williams to hire him for the newly opening terminal on the recommendation of none other than former U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt. Side by side, Gabriel stood just slightly taller than Chief Williams, whose café au lait complexion seemed pallid compared to the African’s chiseled dark face, which was made even more remarkable by a pair of light eyes that sometimes appeared brown or gray.

Williams had heard Gabriel’s story as the public did, in the papers or at the station. Gabriel had been a boy during the first Italo-Ethiopian war that killed his father, a ranking officer in the Abyssinian army of Emperor Menelik II. The war separated him eternally from his mother and any knowledge of her fate. Around 1896 a senior British Army officer, Herbert Kitchener, adopted the boy, who then accompanied the military forces to the Sudan, India, and Egypt. Kitchener returned to England, where in the fall of 1898 he was made Lord Kitchener of Khartoum, but before he left, he placed the boy in a Muslim school in Cairo. Using funds that Kitchener sent him from London, Gabriel determined to perform the hajj—the pilgrimage to Mecca, forbidden to non-Muslims. Though he was born an Orthodox Christian, Gabriel had learned enough of Islam to present himself confidently as a convert named Abdullah Mohammed. Succeeding in Mecca, he continued by camel to the second holy Muslim city, Medina. Spiritually enriched but broke, he accompanied Syrian pilgrims on foot across the desert to Damascus, then went to Jerusalem for six months. His next location changed his fate dramatically.

In 1900 Lord Kitchener was back in Cairo, where Gabriel rejoined him. There the officer arranged for his appointment as interpreter to the British embassy at Constantinople. Gabriel thought Constantinople a fine, beautiful city, and its thousands of people kept him enthralled. “You can learn many languages in Constantinople,” he said. And he studied every language he heard there—over a dozen—for some five years. Gabriel was later transferred to the British consular services, for which he traveled around the world. In Vienna he married an Austrian woman, Therese, with whom he had two children. Gabriel was at the Paris consulate when Colonel Roosevelt advertised in a French paper about his imminent hunting expedition in Africa: he needed an interpreter for his travels, and so Gabriel answered the call.

Although former president Theodore Roosevelt engaged Abyssinian-born George Gabriel as an interpreter in Africa in 1909, the linguist’s American journey culminated at Grand Central as a Red Cap. Baltimore Afro-American.

George Gabriel acquired two souvenirs from Roosevelt’s 1909 African safari. One was a bullet wound to his leg; the other was the colonel’s promise to provide him with employment should he ever visit New York. North America being the only continent Gabriel had yet to see, on December 8, 1912, he boarded the SS Grant in Cuxhaven, Germany, bound for New York, with a letter in hand in which Roosevelt attested to his desirability as a citizen. In January 1913, Gabriel reportedly visited Roosevelt’s home at Oyster Bay, and obtained his host’s letter of recommendation to William Jennings Bryan, President Woodrow Wilson’s secretary of state. Gabriel’s résumé would have been impressive for any man, white or black. He was proficient in thirteen languages and five African dialects; he had served in military campaigns, diplomatic missions, and expeditions of adventure. He bore (and sometimes wore) honors from several sovereign nations. Yet despite his résumé, and despite testimonials to his competence and character from a former president of the United States, Gabriel was informed that he could not qualify as a government interpreter because he was not a citizen.9

Gabriel then obtained a position as the new Grand Central Terminal’s “official” interpreter, some said with Roosevelt’s help. But just a few months after the station opened, the publisher Irving Putnam overheard a foreigner ask at the information booth “if any of the attendants spoke French or German.” The negative reply took him aback. Considering what enormous attention to architectural detail went into the magnificent new terminal, he wrote to the Times, had no one thought “to provide at least one person on its information staff who could answer questions from puzzled, non-English foreigners?” Maybe Putnam didn’t know about Gabriel’s employment there, or maybe Gabriel’s position was overstated. Considering the scrutiny Williams was prone to, as a Negro who was chief porter, it seems odd that a black polyglot interpreter—an African friend of Roosevelt’s, no less—could go unnoticed in such a consequential post. A few days after Putnam’s letter, someone took umbrage at the suggestion that Grand Central disregarded its foreign-speaking travelers. “As a matter of fact, the writer of this letter is the official interpreter of the information bureau,” Edward Witkowski wrote, “speaking the languages in question, and several others.” Perhaps Gabriel’s job description was lost in translation.10

Indeed, while the New York Central management likely hired George Gabriel on Roosevelt’s recommendation, it equally likely assigned him to Chief Williams: the Red Cap force was the only public department then open to black employees. Since distant Africa was a common bond through descent of Chief Williams and his men, the Abyssinian Gabriel was poised to make a powerful impression upon his African-American co-workers. Even a reporter for the New York Sun reflected upon “the fact that in his veins flows the blood of those who long before Christ walked the earth did their part in building an empire.”11

A few years later Gabriel’s remarkable linguistic abilities drew attention. In January 1916 Zoe Beckley reported in the New York Evening Mail that the stationmaster at Grand Central had been confronted with a distraught woman, sobbing incomprehensibly.12 The stationmaster summoned the official interpreter, whose impressive arsenal of eleven languages turned out to be as useless as a wet matchbook. “Send for Redcap no. 20!” the stationmaster then ordered. It may have been Williams who fetched Gabriel, whose repertoire, broader than the official interpreter’s, included the troubled woman’s dialect. If race had disqualified him from taking on this position “officially,” he effectively become the de facto interpreter, pressed into service when needed without additional recompense to his porter’s earnings.13

The romantic incongruity of the Red Cap’s past and present circumstances captivated Beckley, who recounted the worldly nomad’s singular journey. America impressed Gabriel as “the supreme country of the world except in one thing”: it was still a land “where race and color are counted against a man, no matter what he is otherwise.” And apparently no matter who recommended him. “That is why George Gabriel is toting grips at the Grand Central,” Beckley remarked, “one of the recognized callings a man of brown skin may follow.”

Faced with such inherently American obstacles, it’s a wonder Gabriel did not return to the British or French, who welcomed his obvious abilities. But he likely had too little means—and maybe too much pride—to return. And perhaps, like many immigrants, he still found something alluring in America’s promises, however unfulfilled they were. Gabriel stuck it out and served his adopted country in the First World War. In the fall of 1920, a newly naturalized citizen, Gabriel booked passage to Switzerland to visit his Austrian wife and children, whom he had not seen for years. He visited them again four years later, but at some point his marriage ended. By 1927, he was working as a Pullman porter on the New York Central when he decided to resettle upstate in Buffalo, New York. Gabriel became chief of the Red Caps at the Exchange Street Station and stayed there for some thirty years.14

Unlike Gabriel, Chief Williams had not experienced world travel. But the opening of Grand Central Terminal and the growing distinction of black Harlem nonetheless gave him access to a world view. Both enclaves afforded him a singular vantage point, and each would be described as “a city within a city.” “Here we have the largest Negro community in the world,” the renowned black sociologist Kelly Miller said about Harlem, “a part of and yet apart from the general life of Greater New York.”15 And Grand Central, the “gateway to the American continent,” constituted a temple of transportation, with shops, restaurants, galleries, offices, hotels and more that formed a so-called “Terminal City.” James Williams had a foot planted firmly in both places.

One way Chief Williams strove to bridge the discrete worlds of Grand Central and Harlem was through athletics. By 1915 America’s favorite pastime, baseball, was as evident in Harlem as anywhere else in the country. Local fans crowded to attend semiprofessional Negro League games on uptown fields such as Harlem Oval at 132nd Street and Lenox; Olympic Field at 136th Street and Fifth; and Lenox Oval at 145th Street and Lenox. Indeed, the Chief afforded several young athletes a shortcut to redcapping at Grand Central by positioning the baseball diamond as their point of entry.

In 1916, perhaps still inspired by Wesley’s club in Williamsbridge, Chief Williams organized a baseball club among the men at the station. A far more noteworthy outfit than the earlier one, his team garnered fans, particularly at games where the club squared off against the rival Red Cap club from Penn Station. But when the Great War came, the selective draft swept players from Harlem ballfields to European battlefields. Seeing first-class semipro teams lacking star players, Williams sought to make improvements in his own outfit.

In March 1918 a writer in the Age commented that “few aggregations of men can boast of a greater number of activities than the Red Caps of Grand Central Station.” In light of their splendid mutual benefit organization and active civic interests, it was hardly surprising that the men were “now preparing to seek new laurels in the field of athletics.” Not a few lauded Williams for his master stroke in building a team: “Chief Jas. H. Williams, president of the Grand Central Red Caps Base Ball Club Association, and P. F. Webster, better known as ‘Specks’ Webster, the famous catcher, formally of the Royal Giants, have come to terms. Webster was a hold-out for a larger salary. By signing this star the Red Caps will have one of the fastest teams in the east.”16

By May, Williams was advertising the Red Caps B.B. Club, his new traveling team, “composed of some of the former stars of the Lincoln and Royal Giants.” He called on all of “the best semi-pro teams in the country” to book his men for games directly through their manager, himself, at Grand Central Terminal.17

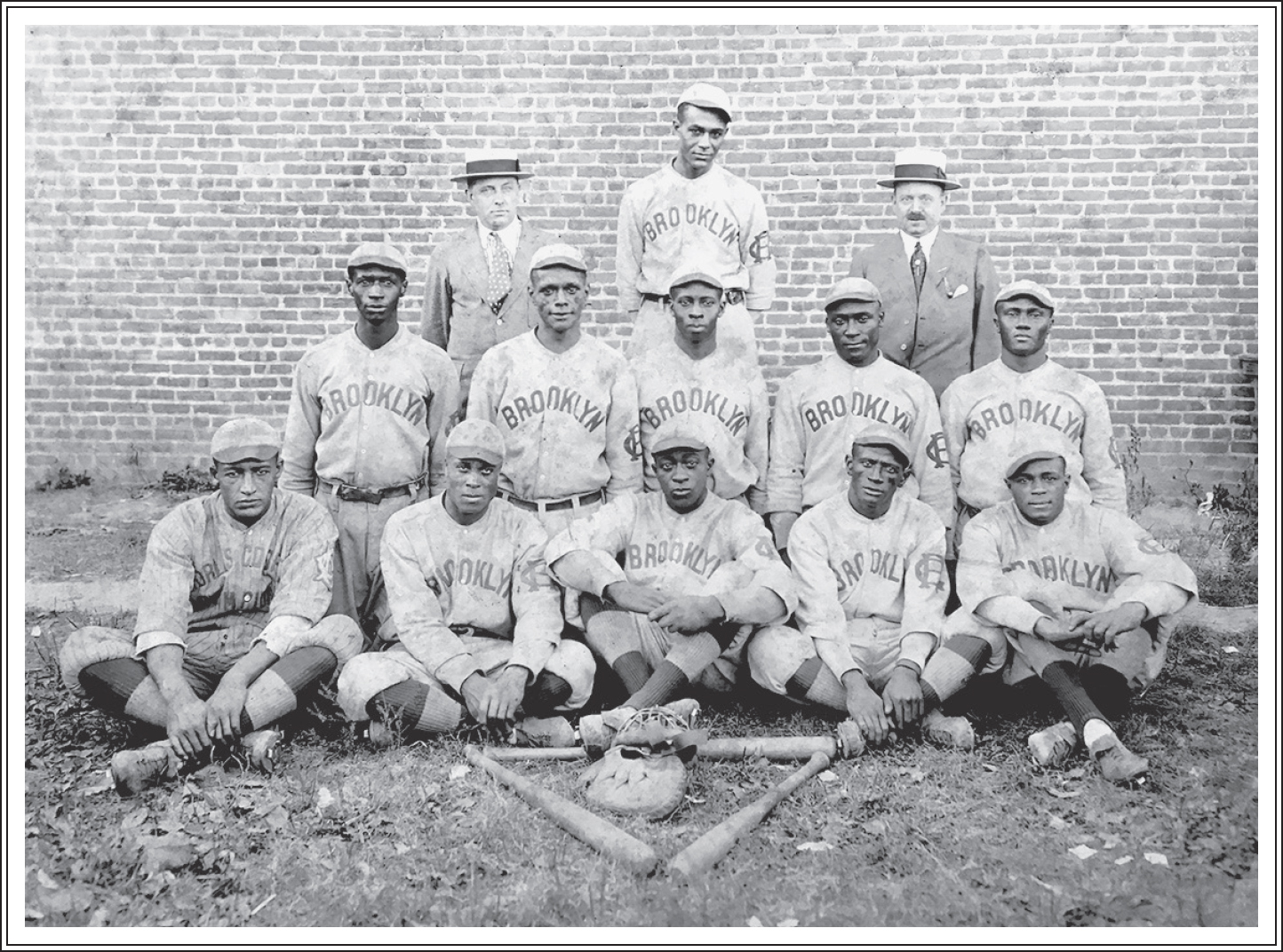

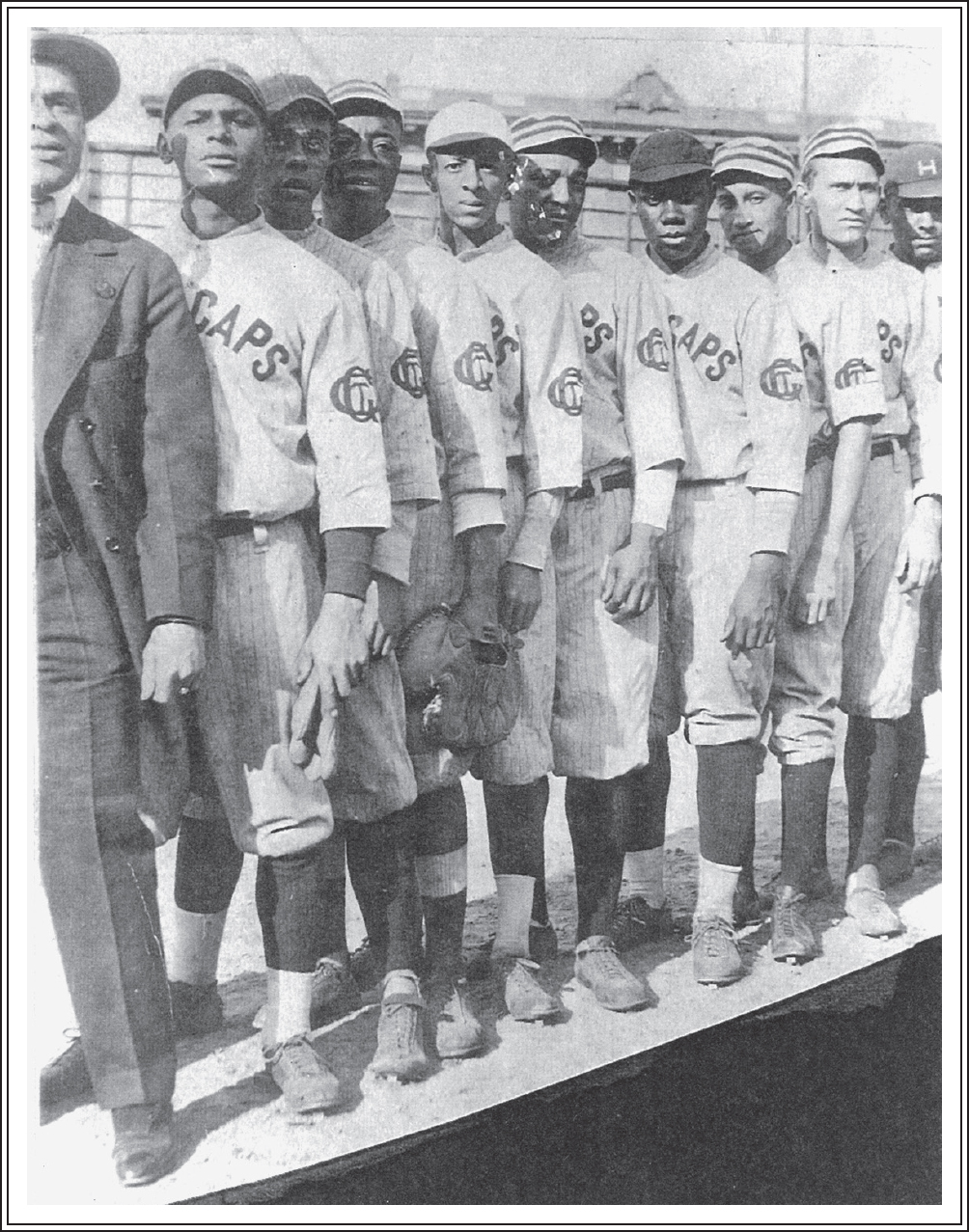

For good measure, Williams assembled his dream team at Lenox Oval, a popular Harlem sandlot at Lenox and 145th, for a photograph. The team’s impressive members included captain and center fielder Charles Babcock Earle (whose prowess the white Brooklyn poet Edna Perry Booth extolled in a number of published verses); right fielder Howard “Monk” Johnson; pitcher Smoky Joe McClammy; and Specks Webster. The men were all smartly uniformed in knickers and jerseys, with RED CAPS boldly arced across their chests, and GCT embroidered on their sleeves. Standing in a black tailcoat at the head of the lineup was their manager, James Williams, with his recognizably proud jaw, at the left margin of the photo.

Chief Williams’s baseball club made an impressive showing on the diamond. But regardless of the team’s good gamesmanship, the ballfield was also a battleground. As Jim Crow pervaded most American activities and enterprises, it also touched every aspect of baseball, from the players and managers to the designation and regulation of ballfields. The most redoubtable figure in baseball bookings and playing fields was Nathaniel “Nat” Calvin Strong, the executive owner of the World Building. Strong, who was white, had been secretary of the National Association of Colored Baseball Clubs of the United States and Cuba, and he long dominated most of the country’s major black teams in the East. Black managers complained that the magnate’s control over dozens of amusement places and parks let him negotiate stifling terms that kept their clubs dependent and stagnant. Not a few black managers and players distrusted his alliances with Tammany Hall bosses: the political machine, with its decades-long influence over the game, could control a site’s leasing terms or its street and transit accessibility. As an enterprising black sportsman, Chief Williams saw Strong as a formidable obstacle.18

In 1918 Chief Williams used the incentive of Red Cap jobs to build a crack baseball team at Grand Central from stars of the Brooklyn Royal Giants (seen at Dexter Park), which rankled powerful owner Nat Strong (top left, with the field’s later owner, Max Rosner, top right). Dr. Bennett Rosner Family Collection.

In 1918, Williams (in a black tailcoat, left margin) proudly shows off his new star lineup of the Grand Central Terminal Red Cap Baseball Club at Harlem’s popular Lenox Oval, at Lenox Avenue and 145th Street. Columbia University Rare Books and Manuscripts Library.

In June 1918, Williams accused Strong of preventing the Grand Central Red Caps from securing choice dates, and he took his complaint to the press. Lester Walton, in his sports column in the Age, noted that some years earlier original Brooklyn Royal Giants owner John W. Connor had made a complaint similar to Williams’s and was still convinced that Strong discriminated against him as a colored ball team manager. Walton urged an immediate investigation, saying “the colored fans should rally to the cause of the Red Caps” if Williams’s claims were true. Walton was nonplussed at Williams’s assertion that “Strong is trying to corner all the colored ball players,” opining that it was in the latter’s “honorable ambition” to secure the best colored team and the best dates he could muster. But to purposefully shut out colored managers was something else again. Walton ventured no white manager would practice it “if it was thought that the colored public would strongly object.”

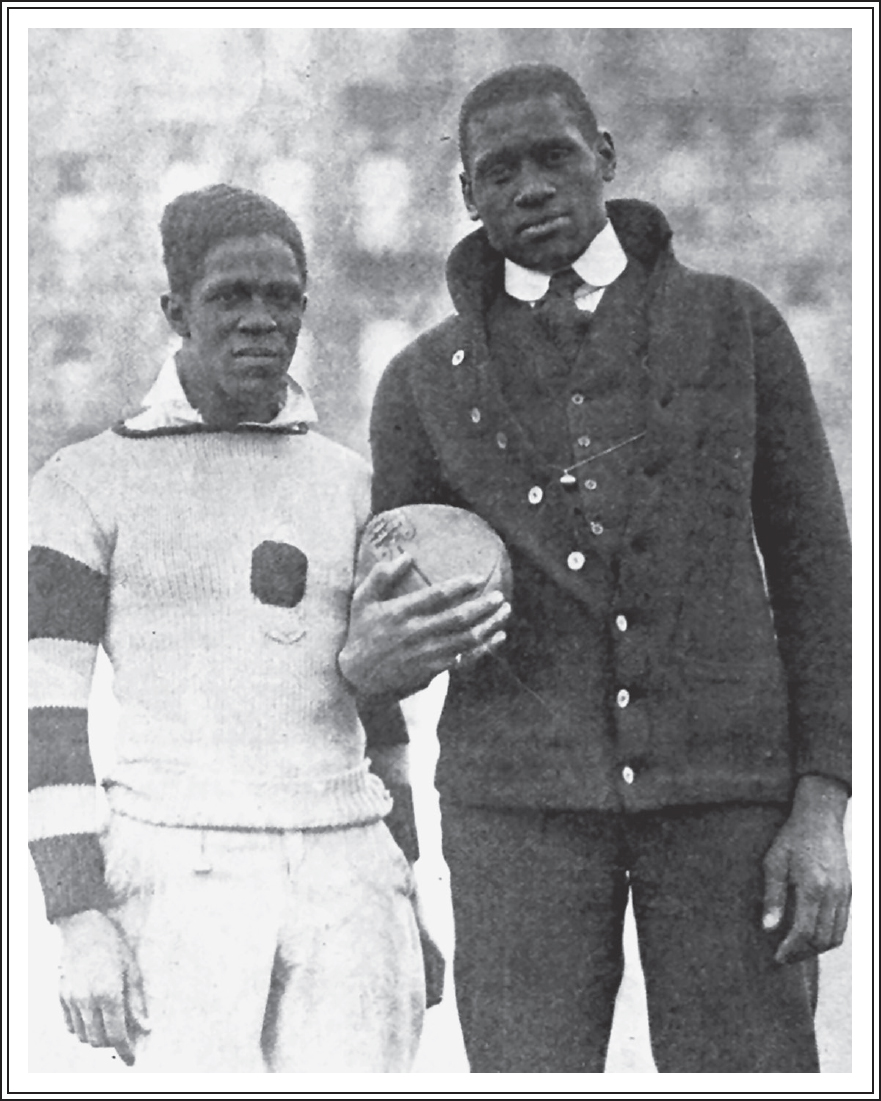

Legendary all-American athlete, artist, and activist Paul Robeson (right, with football coach Fritz Pollard) in 1918, would briefly work as a student Red Cap at Grand Central. The Crisis.

Indeed, while Lester Walton went to bat for Williams’s just complaint, he also took New York’s black baseball fans to task for failing to patronize their own, as in Chicago and other towns. He was not averse “to white managers separating the colored fans from their dimes” if in fair play black managers were in the mix, but he opposed an effort to “get the colored public’s money but keep out the colored manager.” He posited that black ticket-buyers had the power to bring about change. “If the colored fans demand that Manager Williams’s nine be given desirable dates their wish will be gratified,” Walton wrote. “But it will take more than street-corner, barber-shop and bar-room talk to turn the trick.”19

Though Chief Williams was the acknowledged creator and manager of the baseball team, Brooklyn papers occasionally wrote of “Charles B. Earle’s Grand Central Red Caps, the best colored team in the country.” While that attribution was apt to please Williams—for it implicitly acknowledged his coup in obtaining Brooklyn’s star player from the Royal Giants—Earle’s defection was bound to vex Nat Strong. Walton gave Strong column space in the Age to answer Williams’s charge that he was discriminating against the Red Caps on playing dates.

Strong claimed that several of his Royal Giants players would have been out of work were it not for him keeping the ailing club in business. He also described how, at various times after the season had closed the previous fall, half a dozen players had asked him for a letter of recommendation to the New York Central—which he wrote. And each man had prophesied aloud about what a great team the Royals would have next year—that being the season now at hand—until mid-March, when they suddenly announced they had decided to play with the Grand Central Red Caps. Strong suspected their strategy was to undermine his ability to muster a team in time.

The controversy put Strong on the defensive to establish his turf boundaries. He professed his ability to secure Royal Giants’ games “on my own personal acquaintance with various teams and managers all over the country,” but he obviously resented the Chief’s peculiar abilities. Williams had somehow influenced his club men to trade in their Royals uniforms for Red Cap jerseys; and he somehow had been able to offer his players steady gainful employment season round. Strong patronizingly disclosed Williams’s stated desire (so he claimed) “to get into baseball and make some big money,” yet he himself, the white magnate of colored baseball, was that very dream personified. Strong’s argument lapsed into condescension as he beseeched Walton to “imagine when all a man has to offer to a player is an opportunity to carry bags at the Grand Central Depot 10 hours a day.” But had the fact of his players’ acceptance signified nothing? “I am not afraid of my reputation being assailed by such a man as Williams,” Strong lashed out.20

Yet “such a man as Williams” had not been the first black manager to complain about Strong’s monopoly, or to reproach his own race for putting up with it. “The ball players out west follow Rube Foster,” read a Defender editorial, evoking the black baseball player and manager who founded the Negro National League, “not the white man.”21

“I know where I stand among the colored folks,” Strong wrote assuredly, “aside from Williams and those associated with him who tried to kill colored professional baseball.” This was an accusation Walton and his readers knew to be patently untrue, a case in point being Earl Brown, a star student athlete who would join the Chief’s team years later.

“We were fresh from the sticks,” Brown, a Virginia-born journalist and politician, alluded to his rural origins when recalling how he first met Chief Williams. In the early 1920s, Brown and a schoolmate from Harvard (where he would graduate, class of 1924) had come down from Massachusetts to look for work in New York. An influential friend who knew they were good baseball players sent them to Grand Central to look up Captain Earle—Charles Babcock “C. B.” Earle, Williams’s assigned head coach of the Red Cap team—to try out for the ball club and “incidentally, to get jobs toting luggage to make money.” When Brown met Earle, he boasted of his and his friend’s prowess on Harvard’s varsity baseball team. Earle heard them out, then located the Chief. Brown recalled feeling intimidated when Chief Williams appeared; his stern look belied the sparkle in his eyes as they nervously repeated their spiels. “What d’ya think, Cap’t?” the Chief asked. No harm in trying them out, Earle supposed. “All right,” the Chief agreed. “We’ll take ’em up to the field with us this afternoon and see what they’ve got.”

Brown and his schoolmate practiced on the diamond with the Red Cap “nine” that afternoon, and their performance convinced the Chief to have them report for work early the next morning. He of course relished getting to play ball with the Chief’s Red Cap team. But Brown had ultimately ventured to Grand Central from Harvard for the gainful employment, as the older players had done from Brooklyn during the war.

In August 1914, a year and a half after the terminal opened, armed conflict broke out in Europe. The United States had entered the war in April 1917 to “make the world safe for democracy.” But as Williams knew, the American ideal of democracy was at odds with its grimly discordant home front: on July 2, 1917, white mobs went on a rampage in East St. Louis, Illinois, wantonly massacring nearly one hundred black citizens in broad daylight. Many decried the terror as the culmination of some three thousand lynchings and murders committed against American Negroes over the past three decades. The incident pitched the country into expressions of national shame and remorse. In New York, black citizens organized an action in midtown Manhattan to draw attention to the outrage.

On Saturday afternoon, July 28, 1917, some fifteen thousand black men, women, and children, led by the NAACP, marched down Fifth Avenue from 57th Street to Madison Park at 23rd Street. By prior agreement, the participants in the Silent Protest Parade remained profoundly mute as they followed the slow, steady pulse of a muffled drum. They chanted no strident slogans but instead carried bold banners that read MAKE AMERICA SAFE FOR DEMOCRACY; AMERICA HAS LYNCHED WITHOUT TRIAL 2,867 NEGROES IN 31 YEARS AND NOT A SINGLE MURDERER HAS SUFFERED; WE ARE EXCLUDED FROM THE UNIONS AND CONDEMNED FOR NOT JOINING THEM; PUT THE SPIRIT OF CHRIST IN THE MAKING AND EXECUTION OF THE LAWS; and Theodore Roosevelt’s stock promise, A SQUARE DEAL FOR EVERY MAN—T.R.

The Silent Protest Parade was purportedly conceived by the Rev. Frederick Asbury Cullen (father of later world-celebrated poet Countee Cullen) of the Salem Methodist Episcopal Church at Seventh Avenue and 132nd Street.22 On the organizing committee were Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois; the millionaire businesswoman Madame C. J. Walker; and the pastor of Abyssinian Baptist Church, the Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, Sr. Williams’s old neighbor from West 134th Street was also on the committee, Dr. Ivison Hoage. The names of Manhattan Lodge Elks on an NAACP list of supporters suggests that Williams’s own participation in the Silent Protest Parade was also likely, if maybe tacitly.

Like any social justice organization, the NAACP considered it paramount to engage young members. The previous spring the writer James Weldon Johnson, the NAACP’s field secretary at the time, vouched for the College Men’s Round Table, saying the students promised to cooperate in any campaign aimed at “increasing the membership of the local branch and arousing general interest in the work of the Association.” According to the Chicago Defender, its members came from “every leading college of the east, namely, Harvard, Yale, Dartmouth, Columbia, Brown, College of the City of New York, New York University, Fordham College, Cornell University and University of Chicago.” Many of the Round Table young men must have needed to earn money for school in the fall. Given the race-barred job market, it was a sure bet that a good number sought Chief Williams to hire them as Red Caps.23

The Silent Protest Parade passed near the terminal, and since Red Cap porters were necessarily walking information booths, the Chief might have considered how they might tactfully answer the public’s questions. His entirely African-American corps, relegated to work like pack mules, surely felt personally touched by the horror in East St. Louis and no doubt shared the indignation of a protest banner that read WE ARE MALIGNED AS LAZY AND MURDERED WHEN WE WORK. Chief Williams might easily have given a number of the men leave to “staff” the crossing at 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue a block away, where they could contribute to the passing march. “‘Red Caps’ from the Grand Central Station took delight in telling the curious what it was all about,” Lester Walton wrote, “preferring to perform such service for the time being to making tips.” Indeed, the opportunity to act as an impromptu speakers bureau for the Silent Protest Parade might have been worth any pecuniary sacrifice that Saturday afternoon.24

The Silent Protest gave rise to the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, which failed to pass Congress in 1922 and several times after that. Its failure fueled the broad political defection of the nation’s black voters from Republican to Democrat, and it set the stage for massive civil rights demonstrations and protests to come.

Williams was well-known for rallying his Red Cap porters to support “racial uplift” causes. In 1913 they had contributed $150 during a twelve-day campaign to raise $4 million to build a Colored YMCA and YWCA in Harlem.25 In 1916 they participated in raising funds for the Booker T. Washington Memorial Fund, to honor the renowned educator and orator who had died the previous year. For the memorial campaign, Chief Williams’s Red Caps and their counterparts at Pennsylvania Station diligently saved “five cents a day for twenty days.” At Grand Central, Williams gave three dollars, and each of his men one dollar, to a total contribution of $175 (about $4,247 today). At Penn, Capt. W. H. Robinson gave $1.75, but only a few men (including Chief Williams’s son Wesley) gave one dollar, and the others pledged fifty cents, for a total of $75 (about $1,820 today)—a possible indication that Penn was the less lucrative of the two stations for Red Cap porters.26 The organizers explicitly commended Williams and Robinson, lauding them as “philanthropic knights of the grip” and for showing up the so-called “big Negro” business professionals who conspicuously failed to contribute.27

In the spring of 1917, after the United States entered the European war, Williams had reason to take pride in his men’s out-ofpocket show of enthusiasm. The New York Central’s president, Alfred H. Smith, was also chair of the Liberty Loan Committee of Railroads, which fueled the sale of war bonds systemwide—from executives down to errand boys and porters. One railway trade journal cited the Red Caps as over a third of the roughly 150 various depot attendants who took bond subscriptions, observing that they “in most cases pa[id] cash which was not taken from savings banks.”28

In the summer of 1918, the government’s “work-or-fight” rule mandated an immediate draft of unemployed males. That caused a notable attrition of Grand Central’s Red Caps, whose numbers dwindled to only sixty-five men. Chief Williams explained that most of the men inducted were of draft age, and many chose to fight, but a number of others were aliens, some with ten years at the station, whose lack of papers “proved detrimental to them” when the rule went into effect.29 Yet regardless of the depletion of the workforce (which may have increased by fall), Chief Williams personified the Red Caps’ philanthropic zeal, as when he organized 110 Red Caps that October to buy Fourth Liberty Loan war bonds. They “went over the top . . . some buying as much as $500 worth of bonds,” outdoing all other terminal groups by collecting $20,000, the New York Age reported.

This came on the heels of another recent contribution, that the same item noted: “Three weeks ago Chief Williams and his co-workers contributed $111 to Haywood Unit no. 14 to help further its canteen work.”30 Haywood Unit no. 14, located at 2388 Seventh Avenue, boasted that its canteen had “social rooms, bedrooms, pool and billiard tables, dining rooms and a well-kept back yard.” Both “colored and white war workers in large attendance” participated that summer in opening the canteen, which might have infused a degree of optimism about the waning of racial prejudice, especially alongside headlines proclaiming “no color line” for Negro troops in the ranks of our French allies.31

More than a dozen Grand Central Red Caps volunteered for service in Europe, And the military recruited from the Red Cap ranks sixteen commissioned officers, three of whom were in France with the 369th Regiment, the “Harlem Hellfighters.” Chief Williams rallied his attendants to furnish all manner of clothing and gear to their fellow Red Caps in the army, from socks and scarves to “a pair of army regulation field glasses” and “a wrist watch” and “colored [news]papers.” One paper noted that “Chief Williams writes to his former comrades every ten days.”32

Army Mess Sergeant Chester A. Wilson, who had enlisted in June 1916, was one who wrote back to him.

Dear Chief:

Since I wrote you last I have received two letters, two packages of papers and the precious candy which you sent me. I certainly appreciate your kindness and will always feel obligated to you. Tucker is here with me and helped to enjoy the candy and papers. “Dr.” Ransom is stationed at another place, so I will have to tell him about it when I see him.

Well, this is our second attempt on the Germans, and believe me the same old tradition stands good. These boys will all give a good count of themselves every time they have a chance. You can tell them with confidence that this regiment is making good. Wish I could relate some things to you, but the censor will only cut it out. So I will wait and tell you when I return, if I am spared to do so. The weather is very hot today and everything is quiet except the artillery. We can tell that they are near. Battles high up in the air are common sights. Gee, whizz, you should see them.33

One aspect of the Chief’s diligence at Grand Central suggests his likely affiliation with the Circle for Negro War Relief. Established in November 1917, the circle was a women’s initiative dedicated to promoting the welfare of black troops and their families impacted by the war. Its vigorous activities included sending comfort kits and chewing gum to the soldiers overseas. It was spearheaded by the white reformer Emily Bigelow Hapgood, its president, who built up a formidable coterie of white and black activists. According to the writer and activist Alice Dunbar-Nelson, the circle’s influence on black participation radiated across the country, similar to the Red Cross.34

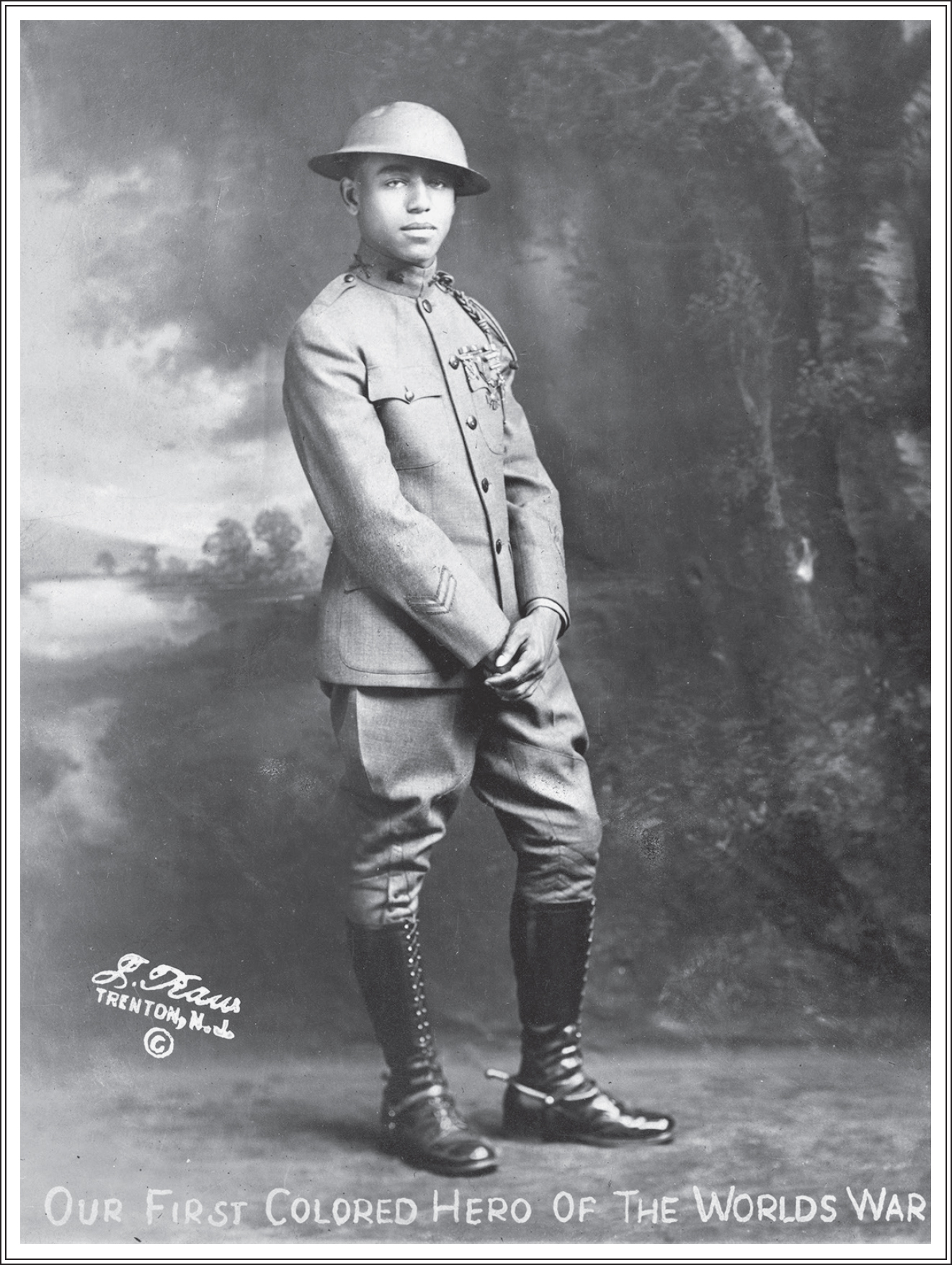

On November 2, 1918, Chief Williams helped celebrate one of the circle’s major public events, in Carnegie Hall. Billed as a “Patriotic Evening,” some two thousand citizens, black and white alike, attended the fund-raiser to benefit the Circle for Negro War Relief. W.E.B. Du Bois presided over the program. The evening’s star attraction was the war correspondent and humorist Irvin S. Cobb who, despite his southern Confederate stock, had recently written an eyewitness account of the discipline and valor of the Negro fighting troops in France.35 The two famous regiments—the 367th “Buffalo” Infantry and the 369th Harlem Hellfighters—had shown so much patriotism on the battlefront that the Americans and the French would decorate over a hundred of them. The segregated Hellfighters had trained under French command. Cobb lauded two black soldiers, Henry Johnson and Needham Roberts, who thrashed twenty-odd enemy Huns on their own. France awarded the pair the coveted Croix de Guerre, distinguishing two black soldiers as the first Americans to receive its highest military honor for extraordinary gallantry. The audience greeted Cobb’s testimony with riotous bursts of enthusiasm.

The special guest who followed Cobb was Col. Theodore Roosevelt, the former president. Williams knew “Teddy” well: when his son Wesley applied to the city’s fire department—the only black applicant out of seventeen hundred—Roosevelt had purportedly written him a character reference. Roosevelt’s personal appearance at this “Patriotic Evening” was highly symbolic: in 1906 he had received the Nobel Peace Prize (he was the award’s first recipient), and he had recently contributed $4,000 of $45,482.83 in securities and cash to the colored YWCA War Work Council. He explicitly earmarked the purse in support of the Hostess House at Camp Upton, Long Island, “for colored troops and in work among colored women and girls in and about the camps and cantonments.”36 Roosevelt had originally donated his prize to Congress to establish a permanent Industrial Peace Committee to promote “fair dealings between classes of society.”37 But Congress never organized the committee, and the onset of the Great War prompted Roosevelt to petition for the return of the funds.

If “Teddy” was ever a great favorite of African Americans, his personal appeal now on behalf of the Circle for Negro War Relief stood him in good stead as he encouraged the crowd to pledge donations to the circle. Their cheers shook the great concert hall as Roosevelt boomed his own promise to do all he could “to aid you to bring nearer the day of the square deal.”38 He would not realize his mission; he fell ill the following week, rallied, then died two months later, barely a week into the new year.

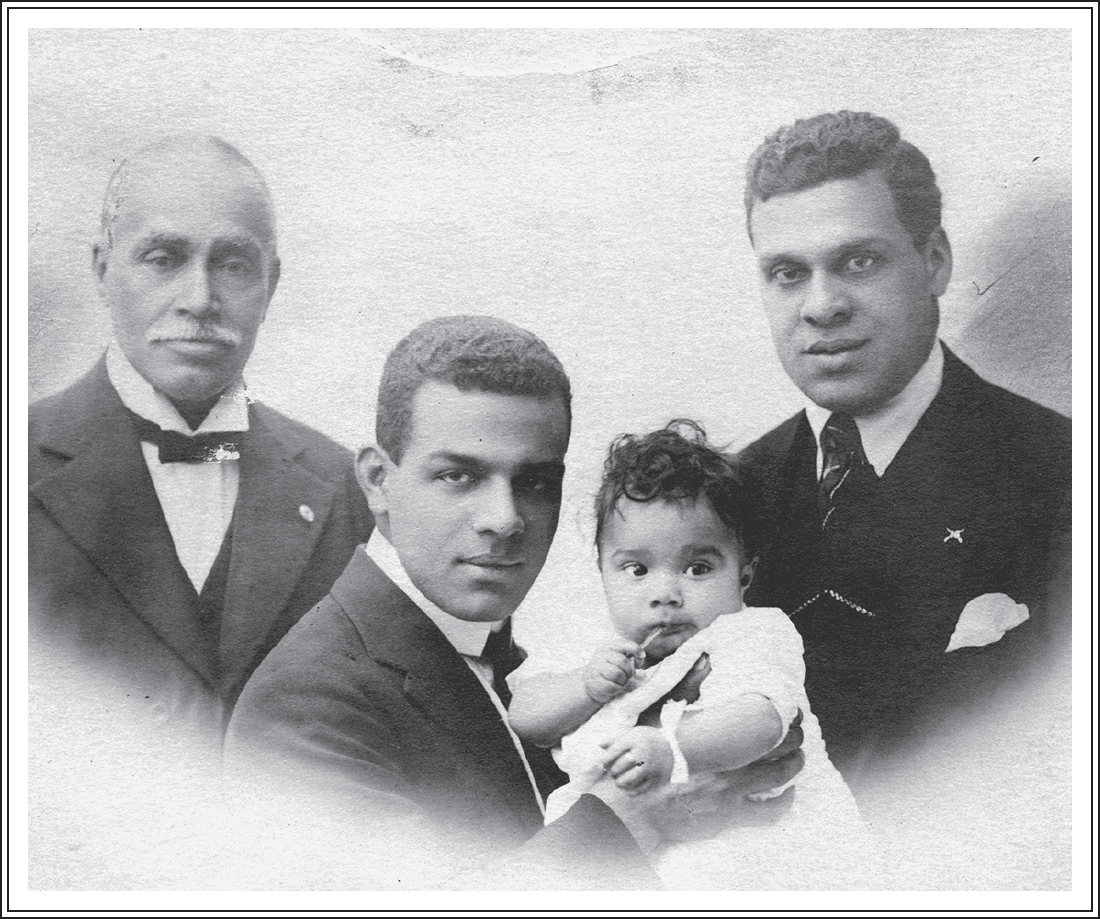

It had happened that one of the two heroes whom Cobb mentioned was now back home in New York: Needham Roberts. That Roberts’s exultant return coincided with the Circle’s big New York fund-raiser was timely. The organizers hastened to adjust the program “to have the colored hero introduced to the audience.” To that end, Chief Williams must have seemed an obvious liaison to Roberts. The Williams family had been in the news all summer, due to his feud with baseball czar Nat Strong and his son Wesley’s auspicious application to the fire department. In October, the NAACP’s annual children’s issue of the Crisis illustrated a verse, “The Black Madonna and Her Babe”—by Lucian B. Watkins, the “Poet Laureate of the New Negro”—with a photo of four generations of Williamses. The image, though captioned incorrectly, was of the senior John Wesley Williams and the Chief, both framing Wesley, who is holding up his infant son James II.39 Between Harlem and the Terminal City, the Chief was being lauded for his organizing around the Fourth Liberty Loan and other war work, and his rapport with Grand Central’s Red Cap doughboys. This timely, favorable attention would have made him suitable for the task of chaperoning Roberts, Harlem’s most famous soldier who had escaped the stark hell of Europe’s battlefields, to the opulent paradise of Carnegie Hall.

A miscaptioned photo of senior John Wesley Williams and the Chief—each framing Wesley holding his infant son James II—pairs with a Lucian B. Watkins poem, “The Black Madonna and Her Babe,” in the October 1918 issue of the Crisis. Crisis, October 1918.

On November 2, 1918, Chief Williams accompanied Needham Roberts—American war hero whom France decorated with its Croix de Guerre—to a “Patriotic Evening” at Carnegie Hall. Robert Langmuir African American Photograph Collection, Emory University, Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library.

Private Roberts had only to take a step across the stage to steal the thunder from both Roosevelt and Cobb. At the young warrior’s appearance, every man and woman in the hall shot to their feet. The celebrities urged him to speak, but the explosive ovation may have stunned him into silence. And he needn’t have spoken. The Hellfighter’s bearing spoke for itself as he stood onstage before the adoring crowd, “resplendent with distinguished medals and service stripes awarded him by the French for exceptional gallantry in action.”

The program’s overall mood was optimistic. Lt. Fred Simpson led the Fifteenth Regiment Band; the composer J. Rosamond Johnson, director of the Music School Settlement for Colored People, played piano; Roland Hayes, the race’s leading concert tenor was in exceptional voice with the Fisk Jubilee Quartet; and black nurses acting as ushers in the great hall appeared angelic in white uniforms. Cobb, conveying his sense that the war’s end was in sight, quipped that anyone wanting to talk of the world war as a present event “will have to hurry.” The mood was indeed also one of encouragement. “There were many nice things said last Saturday evening at Carnegie Hall,” Lester Walton mused, “but the nicest of all was the statement that after the war the Negro over here will get more than a sip from the cup of democracy.” Covering the event, the Age ran a long front-page article with a photo showing Pvt. Needham Roberts and his three brothers standing outside, enjoying cigars with “J. H. Williams, Chief of Grand Central Red Caps.” All are smiling for the camera, as if to rekindle every dimming heart on the home front.

Having made it to Carnegie Hall, some might have quipped, what was left for the war to do but end? Indeed, it did end, little more than a week after Cobb’s prescient quip at the “Patriotic Evening.”

In the late 1910s, Chief Williams’s parents had moved to a ground-floor Harlem tenement apartment at 19 West 131st Street. Charles Ford Williams Family Collection.

Four days before the signing of the armistice on November 11, 1918, a false report had ignited the city into spontaneously jubilant celebration everywhere. Workers and residents poured from buildings, crowds paraded, paper litter was deployed as confetti, and the renowned tenor Enrico Caruso sang from his fifteenth-floor hotel balcony. Chief Williams felt reasonably relieved and proud. The end of the war would soon return his baseball players home, and upon their arrival, he organized potentially “one of the strongest colored teams in the East” to welcome them.40 At Grand Central, Red Caps went “cake-walking through the concourse behind one porter who was pushing an invalid chair in which was a stuffed figure of the kaiser.”41 Two months after the armistice, on February 17, 1919, some three thousand uniformed black men—Hellfighters of the 369th Infantry—paraded up Harlem’s Lenox Avenue to 145th Street.42 Many would later pin the birth of the Harlem Renaissance on that date.

But in the aftermath of the war, Harlem was not quite finished with Europe. “Harlem is like Paris; indeed, we may aptly call it Black Paris,” a Harlem writer observed, noting that the City of Light had long been slandered as decadent. “What Paris is to Europeans, Harlem is to the American Negro. It is the finest Negro city in the world, with broad, tree-bordered, parked avenues, Negro residential streets such are seen nowhere else, alert, well-dressed, energetic people. Brokers, teachers, preachers, physicians, lawyers, politicians, singers, composers, poets, novelists, editors, musicians—Black Paris indeed!”43 Across the ocean, some black musicians like Louis Mitchell and his ragtime band the Seven Spades had been the toast of London, and they remained to conquer Paris. Their sojourn would be as influential as that of any ambassador, speaking the common tongue of jazz.44