CHAPTER 7

“A Sweet Spot in Harlem Known as Strivers’ Row”

And you can have your Broadway, give me Lenox Avenue,

Angels from the skies stroll Seventh, and for that thanks are due,

To Madam Walker’s Beauty shops and Poro system, too,

That made them Angels without any doubt.

—W. C. HANDY, “HARLEM BLUES,” 1922

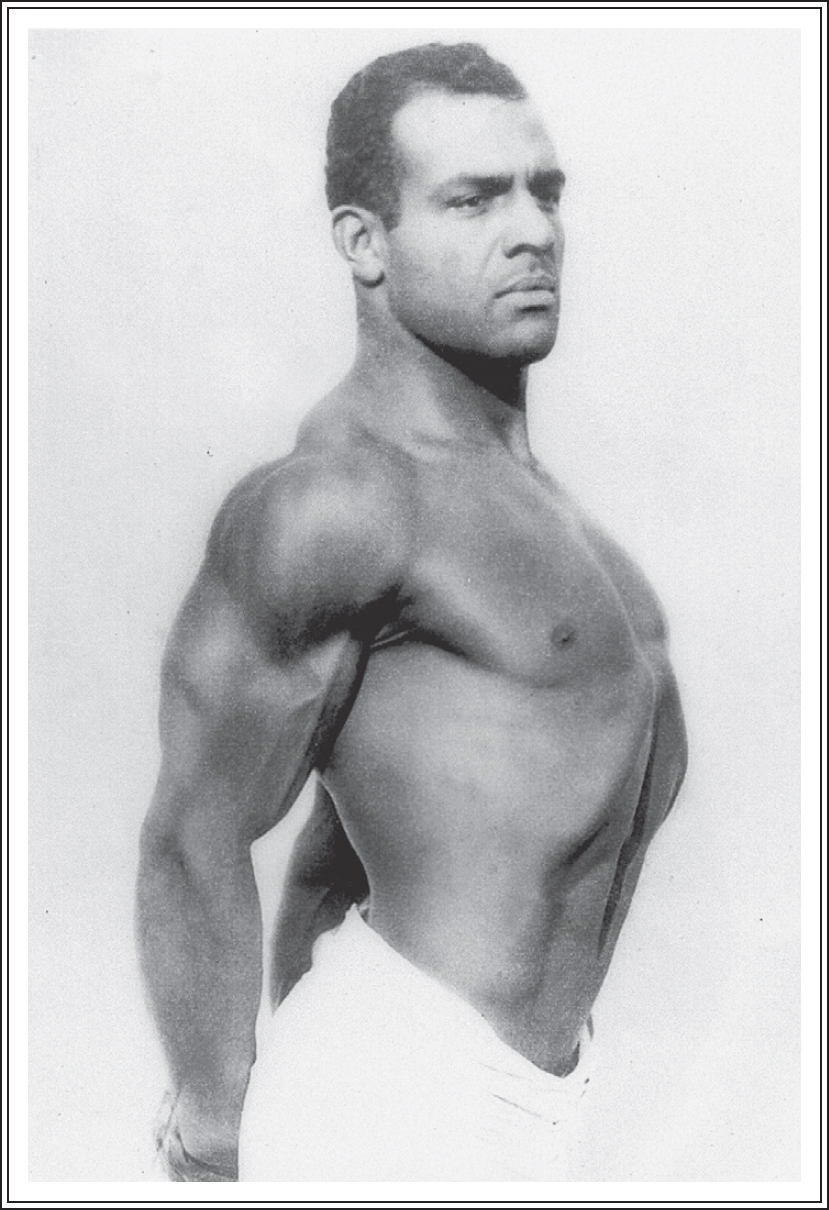

In mid-August 1918, a couple of weeks after Chief Williams’s fortieth birthday, a small item in the Chicago Defender mentioned that he had left for his annual Canadian vacation at the hunting lodge of the ex-governor of Vermont. By sheer coincidence, while Williams was away, the same day’s paper announced that Wesley passed the civil service examination for the city’s fire department. What was more, as a call from home probably confirmed, “Wesley Williams passed the physical test with 100 per cent.” The news spread like a fire itself, igniting the black press and much of the white. Articles made much of Wesley being a devout teetotaler and nonsmoker; some even enumerated every diameter and circumference of this physically perfect he-man. Though the Chief must have missed being home during this momentous news, he was no doubt elated to share it among his angling pals. His son, who had been the only black candidate out of seventeen hundred applicants, was the only one to score perfectly on the physical exam.1

Wesley’s score surprised few. Now turning twenty-one, he was not only an all-around athlete but the protégé of a white professional exhibition athlete, Charles Ramsey. “He happened to live next to an aunt of mine,” Wesley said of his mentor, who had lived at 32 West 137th Street, a Harlem walkup of predominantly black working-class households. Born a British West Indian in 1886, Ramsey had emigrated to the States in 1904 and become an acolyte of health guru and publisher Bernarr Macfadden, the “Father of Physical Culture.” As Ramsey eyed Wesley during the fire department’s physical, he could read the sinews of the lad’s weightlifting experience as clearly as a name tag.

While Wesley Williams became the first black fireman in Manhattan, he was not the first in the city: that honor belonged to a little-known Brooklyn fireman named John Woodson. Though the Williamses hadn’t met Woodson personally, they knew about him from the papers. He had been on the force since September 1914, appointed to a hook and ladder company in Greenpoint, and he was the city’s only black fireman since the paid department had been established a half a century before. Most of the city was unaware that a Negro fireman even existed on the force. Then on September 12, 1916, almost two years after he had started, Woodson daringly rescued a mother and baby from an early-morning blaze in a Brooklyn tenement. The act finally cinched him recognition: the following summer, Mayor John Purroy Mitchel publicly awarded the obscure pioneer a medal for courage.

In 1918 Wesley Williams was the only black applicant out of 1,700 for the New York City Fire Department, and the only one to score perfectly on the physical examination. Charles Ford Williams Family Collection.

The hiring, performance, and public recognition of Woodson–who was described as “a regular Jack Johnson”–fueled the case for racial parity in municipal services. Writing in the Age, James Weldon Johnson measuredly praised Commissioner Adamson, the fire chief whose Georgia roots had at first made many blacks apprehensive, for displaying “the sense of fairness and the stiffness of backbone” to give Woodson his post. “If there were more colored men like Fireman Woodson and more high officials like Commissioner Adamson,” Johnson challenged, “the race would soon have a fair representation in all the departments of the city.” The Woodson affair no doubt prompted Harlem’s civic leaders to canvass another likely black fireman candidate, this time for Manhattan.2 Chief Williams’s son Wesley was an obvious choice.

Once Wesley Williams decided to apply, the Chief engaged his influential social connections to intercede on his behalf to the fire commissioner: Vanderbilts, Goulds, and Morgans as well as former Vermont governor E. C. Smith—men who owned and used railroads. Former president Roosevelt wrote a recommendation. Yet of all his father’s powerful friends, Wesley felt most grateful to Charles Thorley, the millionaire florist, whom he also recalled as a heavy contributor to Tammany Hall, which ran the city. “He told my father, ‘the only thing they got against your son is that he happens to be a black man,’” Wesley said, “‘but he will stay there regardless of what [fire department officials] like.’”3

Wesley was appointed to start at the fire department on January 10, 1919. As when he was made Chief of the Red Caps ten years before, Williams felt heartened that even strangers offered congratulations to the family on his son’s appointment. But despite the Chief’s overwhelming pride in his son’s achievement, he had good reason to be anxious, too. He remembered how cruelly the white cops had hazed his friend Jesse Battle, a strapping six-foot-three giant, with stony silence.

The death of former president Roosevelt on January 6 cast a pall over the country that the Williamses no doubt felt personally—“Teddy” had championed Wesley’s appointment. A few days later, Wesley received a personal letter, also postmarked, with some eerie poignancy, January 6 from Jamaica, Queens: it was from Fireman Woodson, who had read about his appointment. “I know you will be quite surprised to hear from a stranger,” Woodson began his touching four-page letter. “I’m going to ask that you will not consider me as one as I feel that it is my duty as a (Race) man to enlighten you as to conditions that exist in the Fire Department.” Having spent nearly four and a half years in the ranks, Woodson overflowed with practical advice on how Wesley might deflect a most certain chilly reception: “You’ll find quite a lot of jealous and narrow minded men in the Dep’t, and at times you may feel disgusted, but take a tip from me. When you are assigned to a company do your work and do it as near perfect as you can, above all don’t listen to other lazy men, do everything the commanding officer tells you to do, no matter what it might be do it!”4

On January 10, Wesley commenced his assignment at Engine Company 55 at 363 Broome Street, in Little Italy. He had no sooner reported for duty than the rank-and-file firemen ostracized him. Woodson’s words echoed again: “At times you may feel disgusted.” The fire captain himself took his retirement, effective immediately. He walked out “rather than have the stigma of being the captain of the company where the black man was sent,” Wesley later recalled. Likewise, every fireman in the company requested transfer, indignant at having to work and sleep in the same firehouse with a black man. The department denied each man’s request, but that hardly put Wesley at ease. He was relegated to a “black bed,” Jim Crow quarters that firehouses infamously contrived for the rare black recruit. “I was assigned to a bed right by the toilet in the rear of the firehouse,” Wesley recalled, which put him in earshot of his colodgers’ vows to “burn this nigger up.”5

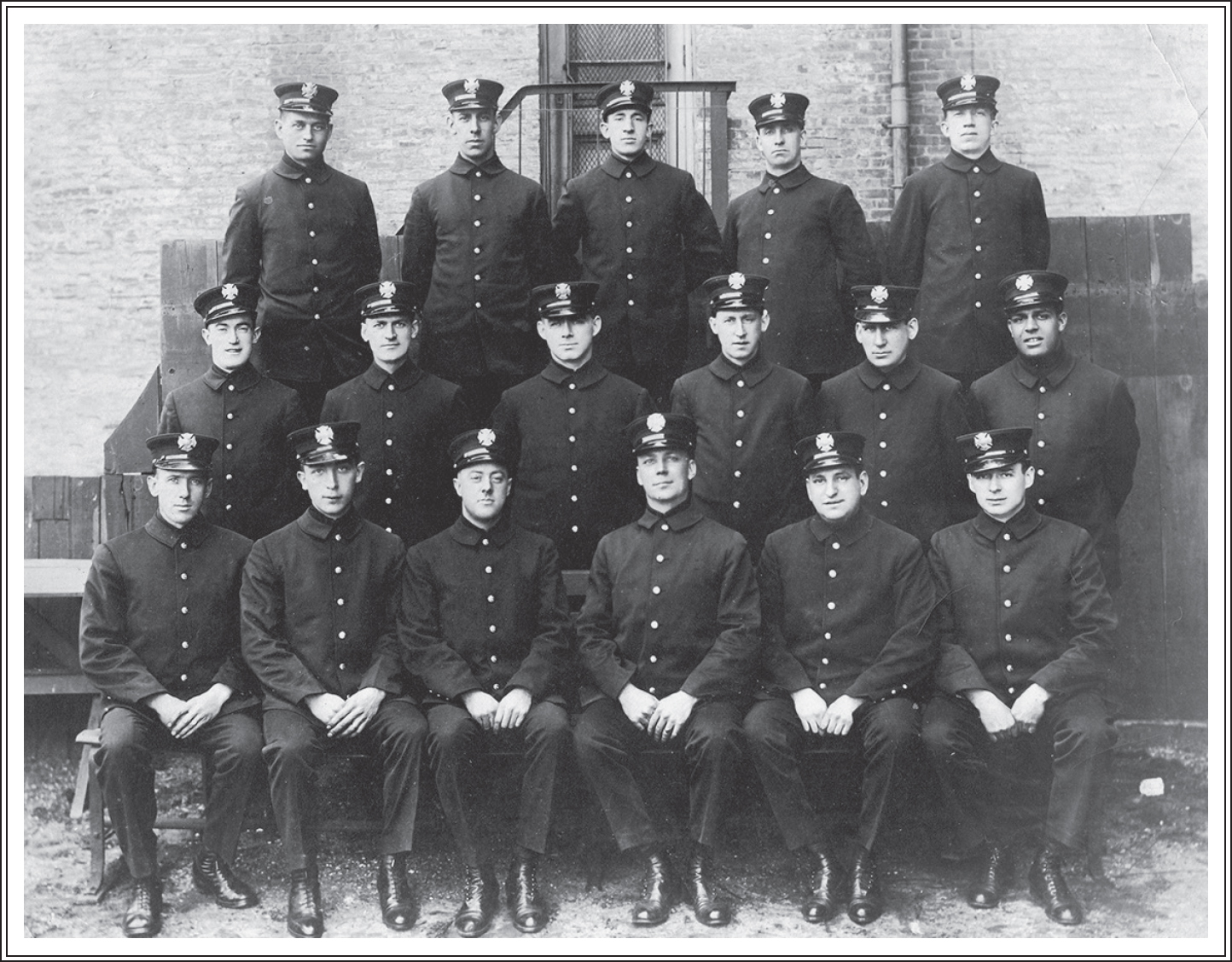

Wesley Williams (right end of middle row) with his graduation probation class of the Fire Department of New York, 1919. Charles Ford Williams Family Collection.

The white firemen soon almost made good on their threat. Within the first six months of Wesley’s probationary term, an explosion summoned the company to the Bowery near Kenmare Street (a continuation of Delancey). The lieutenant, the officer duty-bound to be first to go down and last to leave, ordered Wesley to lead the way into the burning basement. “As the flames rolled over my head, everybody else ran out,” Wesley said. “That left me down there alone in the cellar.” When battalion chief Ben Parker arrived on the scene and asked if all the lieutenant’s men were accounted for, the officer responded that Wesley was still down there. But then the colored rookie emerged from the cellar, having finally put the fire out alone. Wesley’s stinging eyes slowly cleared to the sight of Chief Parker fixing his white co-workers with a withering stare. Whether the men had planned the blaze or it happened as a near-granted wish, they knew their hazing would have to take a new tack. “You were gonna burn him up?” the battalion chief said incredulously. “Looks like he burnt you fellas up.”6

Wesley cited Chief Parker’s action that day as giving rise to his reputation as a valiant “smoke-eater.” But other skills he brought to the fire department seemed to make him at once essential and unpopular. For the three previous years, from age eighteen to twenty-one, he had driven a parcel truck for the Pelham Post Office. Aside from acquiring a keen sense of city geography, the automotive job gave him an even more decided advantage. Many of his white counterparts “had been trolley car operators and truck drivers and stevedores and so forth,” who “only knew about driving horses.” Fire department officials had been trying for weeks to train the men in how to drive a motor apparatus, but the Engine Company 55 station house presented a particular handicap due to its orientation. When Wesley’s turn came to take out the great steam engine and drive it back in, he knew from experience not to try to back in straight, but to do so on a bias. The monstrous apparatus seemed sweetly obeisant to the intuitive hand of a longtime practitioner. Wesley’s effortless performance earned him the appointment of company chauffeur after his three-month probationary period. But though he was naturally qualified to be that engine’s regular driver, the assignment “was resented much by the white men.”7

Wesley came to predict his co-workers’ contrariness. “If I went upstairs, they went down,” he would recall, yet he admitted that their ostracizing had a benefit. Following Battle’s example, Wesley made his solitude constructive. He filled his locker with books by Arthur Schopenhauer, Jack London, Friedrich Nietzsche, William James, and Carl Van Vechten and used his idle hours to read and study without interference. Being shunned also gave him leeway to reclaim Engine 55’s rooftop for himself, adapting the hose tower into a makeshift gym with setups for boxing, weightlifting, and stomach workouts. “They helped to make me a Superman,” Wesley remarked, “the prejudice.”8 Indeed, Wesley was nothing short of a Superman before long: six months into his new career, he helped to rescue an Italian mother and her six kids from a three-story house on 213th Street and White Plains Avenue in Williamsbridge. Though the act went unheralded officially—the prejudice was still too prevalent—it possibly contributed to his growing bond with the Italian-American community that surrounded his firehouse down on Broome Street.

Chief Williams was of course as heartened as his son by John Woodson’s encouragement and invitation to meet. At some point the Chief and Wesley did meet the other fireman: when occasionally in Manhattan, Woodson planned to greet the Chief as he passed through Grand Central Terminal, and Wesley sometimes dropped by to join them.

On July 28, 1919, white and black Republicans alike voted unanimously to nominate the black dentist Dr. Charles H. Roberts as the party’s candidate for New York alderman for the district encompassing Harlem. Roberts was extremely popular and the first black man to gain the nomination. He was a graduate of Lincoln University; president of the Manhattan Medical Dental and Pharmaceutical Association of New York; and organizer of the Children’s Dental Clinic, sponsored by the Children’s Aid Society. He had served on the dental staff of the French Army’s medical division during the war.

Roberts’s platform included advocating for public baths in the district; building an armory for the “Hellfighters” regiment; vigorously prosecuting food profiteers; opposing increases in public transit fares; and establishing a public market in the district.

Chief Williams was named amidst the best-known public figures to endorse Roberts, whose other notable supporters included Lt. Col. Theodore Roosevelt (eldest son of the late president); James Weldon Johnson; W. C. Handy; and Reverend Powell, Sr., of Abyssinian Baptist Church.

Roberts won the election, becoming the first black to serve on the New York board of aldermen. Charles W. Anderson—known as the “Colored Demosthenes” whom President Roosevelt had appointed internal revenue collector for lower Manhattan in 1905—presided over a victory dinner for Roberts at the Libya, one of Harlem’s grandest resorts. Chief Williams acted on the celebration’s dinner planning committee, whose setup was no doubt impeccable: “Floral decorations for the dining hall were furnished by Thorley, the Fifth avenue florist,” the Age noted.9

In October 1919, for reasons that are not clear, the Williamses quit the house at 823 East 223rd Street in Williamsbridge and returned to Harlem. A few years later Sandy P. Jones moved into the house they vacated.

Chief Williams signed a deed for a row house in Harlem at 226 West 138th Street, in a tranquil tree-lined enclave known as the King’s Model Houses. Built in the early 1890s, the exclusive development had refused to sell to blacks, but after three decades it was opening up, and as new black homeowners moved in, it was fast becoming known as Strivers’ Row, a flippant allusion to their middle-class aspirations. Perhaps the new house also harbored his daughter Gertrude’s youthful longings.

Some weeks earlier, on August 22, 1919, Gertrude Williams turned twenty-one. If everybody’s attention had hung on her brother Wesley’s accomplishments for the past year, she now got her time in the family spotlight: two weeks after her birthday, the radiant young woman married William Nehemiah, a jobbing musician of considerable ability.10 Nehemiah (called by his surname for clarity) had worked at Grand Central as one of the Chief’s boys on the marble concourse, but left for the battle trenches in France. A violinist, he played with the “Hellfighters” Fifteenth Infantry NYC Band, organized by the influential bandleader Lt. James Reese Europe and the composer Noble Sissle.

The Harlem Hellfighters returned from war with the taste of champagne. But as a song recorded by Europe’s band asked, “How ya gonna keep ’em down on the farm after they’ve seen Paree?” Parisians in turn were intoxicated by the ragtime and jazz that had crossed the Atlantic and were ravenous for more. “Having fallen willing victims to the melody dispensed by race military bands,” the columnist Lester Walton wrote, “the music-loving public of the French capital is eager to hear a colored orchestra from the States.”11 Parisian club owners gave black American musicians carte blanche. The dashing veteran Nehemiah might well have stoked the young hairdresser Gertrude with notions of living in Paris.

The owner of the Casino de Paris, that city’s most popular music hall, retained Louis A. Mitchell—a well-known New York bandleader and drummer—to assemble an orchestra of fifty American Negro men for his Paris club. Mitchell was arguably the first great bandleader to carry jazz abroad (at the suggestion of composer Irving Berlin, it was said). He had introduced the new music first to London in 1914, and then to Paris in 1916.

The new orchestra, Mitchell’s Jazz Band, was to feature the bandolin, mandolin, guitar, and other stringed instruments that black musicians were known to master, and it was invited to display its versatility in both operatic and ragtime repertoires. Mitchell likely knew Nehemiah’s playing from the Hellfighters band, and recruited him.

Black American musicians responded to Mitchell’s invitation from Paris enthusiastically—it was a chance to win over a welcoming and appreciative international audience, and at the same time to raise the esteem of American Negro musicians for their original talent and craft. It was a grand plan. Mitchell booked passage for his troupe on the SS Espagne on May 6.

But the U.S. State Department, unswayed by the importance of entertainment, denied the musicians’ passports. Passport agent Ira F. Hoyt attached a note to Nehemiah’s application: “Claims to be in 15th Inf. N.Y.C. Band. Does the above fact necessitate applicants getting permission from the Secretary of War?” Mitchell tried to expedite Nehemiah’s and others’ applications, but Hoyt serially rejected them.

This situation shattered Mitchell’s ambitious plan for the fifty-man orchestra. He sailed back to Paris with only seven bandmen, to form Mitchell’s Jazz Kings, who performed at the Casino de Paris for the next few years. Meanwhile “even [white] theatrical managers of prominence and stars of the footlights find themselves marooned in New York,” Walton noted.12 And perhaps a few sweethearts like Gertrude felt marooned, too.

Gertrude and William Nehemiah wed on September 3, 1919, at the Municipal Building downtown near City Hall. The marriage certificate was peculiarly without witness signatures, and the society columns were oddly mute. Indeed, the couple’s civil marriage seemed as much an elopement as had her parents’, whose Strivers’ Row house the newlyweds moved into.

The following spring Gertrude often enjoyed dancing at the new Rose’s Hotel on West 135th Street, where Nehemiah was one of the musical trio, on Saturday evenings. The invitational dances were sponsored by the venerable Aurora Social Club for “the younger element of New York’s exclusive set.”

Rose’s, which had opened in October 1919, was a grand affair. J. W. Rose was a businessman whose Colored Dairy Lunch system had made him a fortune—a local songwriter had dubbed him the “hash and egg king of Harlem.”13 Rose took exception to the Hotel Theresa that loomed over Harlem at Seventh Avenue and 125th Street—it was a citadel of exclusion to Negroes. In response, he bought and renovated three townhouses comprising 246-248-250 West 135th Street and combined them into a palatial race hotel. Though smaller than the Theresa, Rose’s New Transient Hotel, as it was fully called, was Harlem’s—and perhaps all New York’s—first full-scale swank hotel for a black clientele, boasting modern amenities and convenience to all Harlem surface transit lines.

The new hotel started accommodating guests even before its grand opening: white Broadway producer Charles B. Dillingham arranged for “a group of musical artists from Louisville, Ky.” to lodge at Rose’s.14 In January 1920 the National Urban League held a dinner there to formally recognize its local New York branch “as a separately incorporated body.”15 A women’s police reserve feted Lincoln’s Birthday with a tribute to S. Elizabeth Frazier, an auxiliary organizer who was the city’s first black teacher (who once taught at Williams’s grammar school) assigned to a mixed school.16 In April over three hundred guests filled the Rose’s dining room for the grandest banquet to date of the Knights of Pythias Masonic lodge in honor of John M. Royall, a black realtor who had brokered many transactions between white property owners and black buyers and renters in Harlem. Musicians of the Clef Club entertained, so Nehemiah might have played the gig there on his violin, fulfilling the Rose’s promise of “good music day and night” as his best girl danced. Unfortunately, J. W. Rose’s poor health forced him to abandon his successful hotel venture. In late September 1920, all of the Rose’s furnishings were sold at public auction; the police department adapted the building for a temporary station, then razed it ten years later to erect a customized precinct building on the site.

While the closing of the hotel was a loss for black American society, Nehemiah landed on his feet. By September, he was a member of the house trio for the Garden of Joy, a new open-air cabaret at the swank Libya on Seventh Avenue at 139th Street. (And he was probably the same “Willie Neemeyer” who, forty years later, blues singer Lucille Hegamin recollected had accompanied her on violin.) Clarence Muse, a beloved actor from Harlem’s Lafayette Players, emceed the cabaret, which drew crowds of out-of-town visitors.17

“At the Grand Central station is a colored man who probably knows more people than any other Negro in New York,” began a front-page article in the New York Age in the summer of 1923. It featured a photo of James Williams just below the banner, describing him as “head of the Red Caps of the Grand Central station.”18 Barely two weeks later, the death of an American statesman lent the observation a case a point.

On August 2, 1923, President Warren G. Harding died, thrusting Williams’s service into the spotlight. In the late afternoon of August 10, about five thousand mourners pressed into Grand Central’s upper concourse. Col. Miles Bronson, superintendent of the terminal’s electric division, had organized a memorial service there. At five o’clock, the crowd of thousands hushed to the sound of taps emanating from the west gallery. Men bared their heads. The railroad’s choral society sang the late president’s favorite hymns. Another somber tribute had already started ten minutes before in the east gallery, where a relic of the antebellum New York Central station house had been set up. The old stationmaster’s bell had been mute since 1871, but on this day Williams “tolled the bell at half-minute intervals” for the late president.19

In the fall of 1923, Chief Williams was back in the newspapers in his own right. He had announced his latest sports venture: a basketball team. The Grand Central Red Caps were “a first-class traveling attraction and are desirous of booking games with all first-class teams with home courts.”20 The promotion echoed his recruitment of athletic porters into the semiprofessional Grand Central Red Caps baseball club. Some of the West Indian Red Caps were kicking around a plan for a cricket club—as Williams heard out such plans, the media kept abreast of his latest competitive interest. This time it was basketball, a game Williams knew well. Years earlier Wesley had been one of the hardest players of the local Alpha Club, and James had since become an ardent fan of the sport.21

It was basketball’s Black Fives era, referring to the number of starting players, at a time when the game was still racially segregated.22 By 1923, a multitude of the city’s amateur basketball clubs—outfits of various churches, businesses, colored Y’s, fraternal organizations, and other groups—were caught up in a “professional craze” as scores of star-quality recreational players were seemingly raptured up to play-for-pay basketball nirvana. Harlem was an incubator for many new basketball teams.

Wesley Williams (kneeling at left), with Bill Mitchell’s Manhattan Athletic Association team, the later St. Mark’s Bears. Schomburg/NYPL.

Chief Williams figured noticeably in the game’s evolution from amateur to professional. The news of the new professional Renaissance Five playing at the Renaissance Casino coincided with the news of Chief Williams promoting his new Grand Central Red Caps Five. While the “Rens” had imported well-known players, the Chief recruited Red Cap players with impressive reputations, too. He tapped such stars as Ardeneze Dash, a former CCNY and Spartan Club forward; Howard “Monk” Johnson (a veteran of Williams’s 1918 Red Caps baseball team) of the Puritan Club, in Orange, New Jersey; Henderson Huggins, of the Incorporators and Chicago Defender Five; the “sensational” Lester Fial, of the Brooklyn Royal Giants baseball team; and especially Ferdinand Accooe. Fans knew Accooe as the former captain of the Borough A. C. Five and from the Carlton Avenue Colored YMCA (and who was a sports editor for the New York News and Inter-State Tattler).

Through ardent advertising, Williams secured the team’s first out-of-town games in Westchester County.23 The Grand Central Red Caps opened their season in New Rochelle, where they did not disappoint: they vanquished the Orientals on their home court. “Ferdinand Accooe was the outstanding star of the game,” the Chicago Defender wrote. W. Rollo Wilson, sports columnist for the Pittsburgh Courier, echoed praise for the popular “Ferdie Accooe” who shone as the Red Caps “handed Louis Garcia’s New Rochelle Orientals a sweet licking 33-19.”24

Despite their bold debut, the Chief’s fives were not infallible. That same month on Harlem’s Commonwealth Casino court, perhaps they were overconfident, but the “Red Caps did not play together as a team.” The Silent Separates, a formidable deaf Jewish basketball club, easily beat them 26–18.25 (One might wonder if Lucy, the Chief’s wife, acculturated to the deaf world, didn’t wink for the other side.) But generally the Chief’s crack squad made an auspicious showing, making good on one sports writer’s earlier observation that the veteran players of the Red Caps basketball club “give promise of being even better than the Renaissance Five,” a capable Harlem club.26 The sentiment was soon echoed. The Renaissance Big Five, the Commonwealth Big Five, and Pittsburgh’s Loendi teams held the spotlight for some time, but the Grand Central Red Caps “came upon the basketball horizon demanding attention,” another writer admitted, “and they received some, too.”27

Chief Williams’s visibility was rising on the social horizon as well. At high noon on Saturday, November 24, 1923, Harlem arts patron A’Lelia Walker—a businesswoman who had assumed the helm of her late mother’s beauty-product empire, the Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company—held a resplendent “million-dollar wedding” for her daughter Mae. Nine hundred guests were invited, and thousands more people, undeterred by the rain, filled the streets just to catch envious glimpses of the elegant pageant arriving at St. Philip’s Episcopal Church (which had moved up to 134th Street). The Williamses’ youngest child, five-year-old Katherine, was one of the three flower girls in that sumptuous affair. The Chief and Lucy beamed as little Kay and her two companions clutched tiny baskets decorated with rosebuds and bright tulle bows. Their heads laureled with flowers, the three girls resembled blossoms themselves in loose-draping white georgette frocks with fluted lace ruffles and handmade rosebuds. The trio preceded the bride, paving the path of the church’s center aisle with tiny fistfuls of flower petals as they passed.

From Harlem, the Williamses joined the subsequent wedding reception at Madame Walker’s own magnificent Westchester estate, Villa Lewaro, in Irvington-on-Hudson.28 An unrelated item in that same morning’s New York Age also brought A’Lelia Walker and Chief Williams together, and it perhaps suggested an inkling of the former’s invitational who’s who. The paper reported on the formation of a campaign committee to establish a permanent headquarters for the New York Urban League on West 136th Street. The article cited her brother-in-law Edward H. Wilson, owner of the Hotel Olga—which, since the demise of Rose’s, had emerged as Harlem’s now preeminent race hotel—on Lenox Avenue and 145th Street, where Walker housed the wedding’s groomsmen. There was Lillian Dean, best known as “Pig Foot Mary,” whose business acumen at cooking and selling a certain porcine delicacy from a repurposed baby carriage brought her wealth, fame, and Harlem real estate. And the list included Fred R. Moore, editor of the Age, and father-in-law of journalist and politician Lester Walton, who was also on the committee.29

On November 24, 1923, Chief Williams’s youngest child Katherine (left) was a flower girl in A’Lelia Walker’s storied “million-dollar wedding.” Madam Walker Family Archives.

Chief Williams not only counted among Harlem’s multifarious movers and shakers, but drew from them a source of strength that he must invariably have needed from time to time. In the early morning of June 21, 1924, a junket of Missouri Democrats arrived at Grand Central Terminal, to an official reception and fanfare. Williams’s full army of Red Caps, now 350 strong, joined dozens of other terminal employees to flank Mayor John J. Hylan and his retinue on the platform. Police reserves pressed back the crowd, and the municipal band struck up the “Missouri March” as ninety-six delegates from that state clambered out of the Houn’ Dawg Special to a boisterous welcome.30 The southerners had come for the Democratic National Convention at Madison Square Garden, an event destined to be remembered infamously as the “Klanbake.” On the Fourth of July, the convention prompted a local Ku Klux Klan rally in New Jersey, where some 20,000 people railed against a Catholic presidential prospect, Al Smith, whom they decried as governor of “Jew” York. The rally culminated with a cross burning—the likes of which was even closer to home for Williams only three months before.31

In midsummer 1924 Chief Williams attended the monthly gathering of the Red Caps Literary Club in Chicago. The theme of the meeting is not clear, but the weight of a summit conference prevailed amid the dense throng of attendees, prominent speakers, and musical interludes. Robert Sengstacke Abbott, founder and editor of the Chicago Defender and a local NAACP official, delivered a keynote that was “forceful and well received.” Williams was introduced as an honored guest in the august company. Afterward the Chicago clubmen whisked him away to a luncheon at the Ideal Tea Room, where he was introduced to Red Cap organizers from the Northwestern, Dearborn, and Illinois Central stations. Their invitation to the “chief usher at the Grand Central Station, New York City” not only helped the Red Caps of Chicago to accomplish “one of the most encouraging and enthusiastic meetings since their beginning.” It also signified Chief Williams’s status as a principal arbiter of “race” men on the railroads.32

The Williams house on 138th Street was not dormant during his sojourn in Chicago. James and Lucy’s elder daughter Gertrude turned twenty-six that August and took the month off from her job as a dental nurse at Dr. Booth’s in Harlem. She spent her carefree respite in Saratoga Springs and Atlantic City, playing tennis, golfing, and swimming.33 Nehemiah, her husband of five years before, was no longer in the house nor, apparently, in her life.

Gertrude’s theatrical interests were evident that summer: she performed as a principal in a dance and song exhibition at the new Ethiopian Art Theater School.34 The program was staged by Jesse Shipp, Gertrude’s former next-door neighbor from West 134th Street. Amid the social whirl of the theater crowd, Shipp may have indirectly ushered her into a romantic foray with David “Chink” Watkins, a musician friend and pallbearer for the recently deceased Jesse Shipp, Jr.

For the next few years, Gertrude and David kept fast company, palling with some of the highest of Harlem society and brightest of Broadway. That first summer Gert would have been the envy of any young girl entertaining her own stage ambitions: she found herself in the company of Florence Mills, the recent singing sensation of the Broadway shows Shuffle Along and The Plantation Revue. During the three-day out-of-town tryouts for Dixie to Broadway at Asbury Park, New Jersey, the troupe stayed at Laster Cottage at nearby Spring Lake Beach; Gertrude and David joined them there and “spent much time on the beach enjoying surf bathing.”35 The seaside, as essential a social corridor as Harlem’s Lenox or Seventh Avenue, clearly seemed Gertrude’s medium.

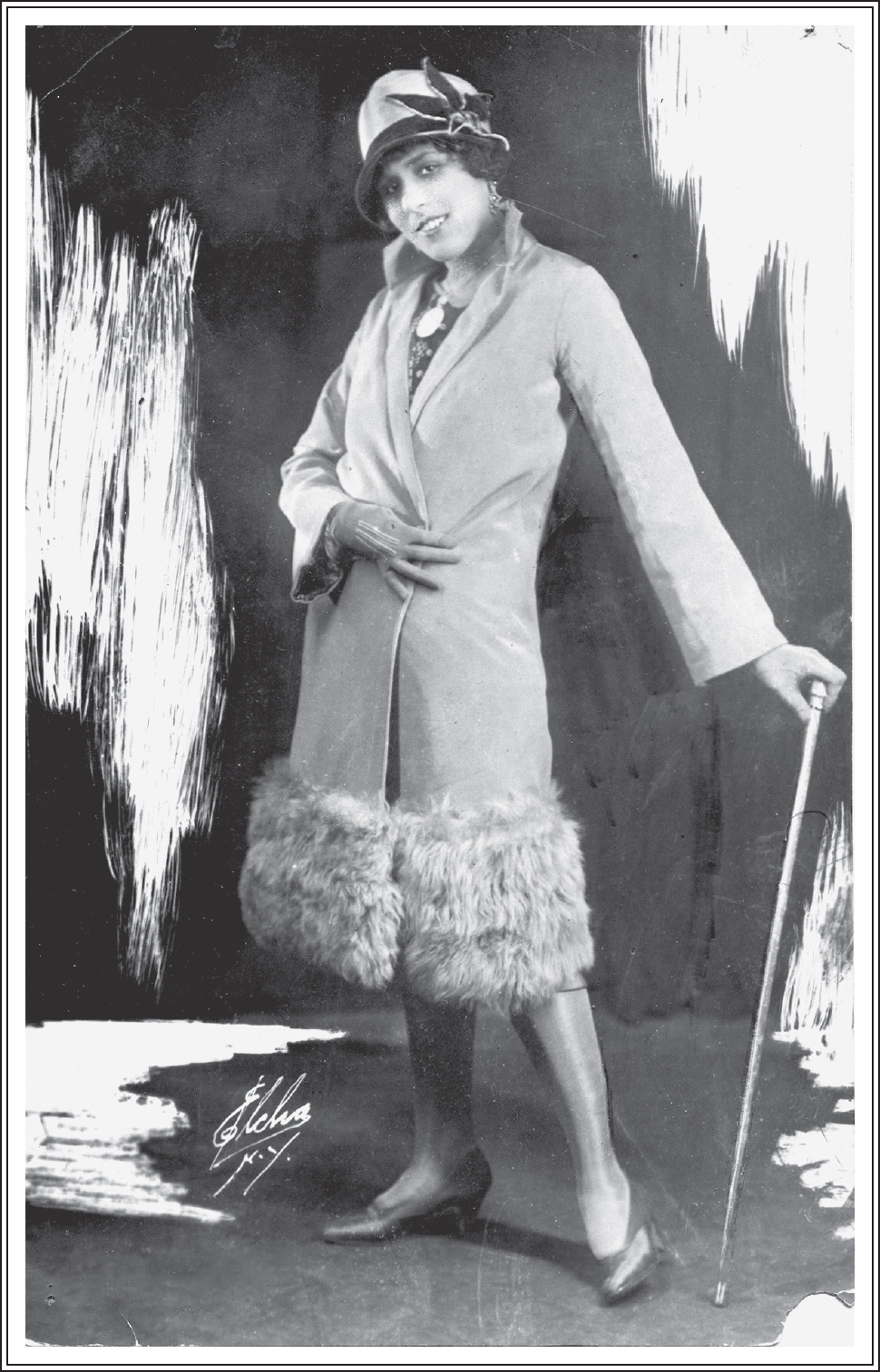

That same summer Gertrude did several modeling stints and beauty pageants, revealing that she possessed a beauty to be reckoned with. She won some local contests (notably for hair bobbing) and was featured in ads for Dr. Fred Palmer’s skin product that promised “Bewitching Beauty for any Complexion . . . in 10 days.”36 She posed for Randolph “Mac” McDougall, a noted black photographer for Underwood & Underwood.

Later, in April 1925 Gertrude modeled in a benefit fashion show for a children’s recreation center, wearing a blond bengaline “Mildred hat,” a creation of Mildred Blount, Harlem’s rising millinery star, who would have an auspicious future in Hollywood. Later that day Gert posed in the same hat for Edward Elcha, a prolific chronicler of Harlem’s vibrant theater and fashion world—and the preeminent black photographer of the Great White Way. Doubtless Gertrude was keenly aware that such legends as Florence Mills and Bessie Smith had preceded her before his camera.

In the summer of 1925 Gert returned to the shore, where she was keenly observed: “Miss Gertrude Williams of New York looked exceedingly well in her style bob. She was very attractively dressed as usual.”37 And during a Labor Day Weekend at Atlantic City, “her bandanna was red, which was so becoming to her tanned complexion,” a columnist observed. “She wore a black one-piece bathing suit and was stockingless.”38

In the late fall of 1926, Gert quit her dental nursing job and went to work as a manicurist for Marcia Louise Lansing, whose posh salon was just steps away, in a townhouse at 2305 Seventh Avenue. The building also housed the New York bureau of the Pittsburgh Courier, which so frequently reported on Gertrude’s activities. “Who Wouldn’t Like Her to Work on Their Hands?” read the caption to a featured photo of her.39 Chief Williams could have smiled as he saw the photo, perhaps recalling that she had practiced on her mother and little sister’s hands.

In April 1925, Gertrude Williams modeled a hat designed by Mildred Blount, who was yet to become a pioneer black milliner in Hollywood, for prestigious black Broadway photographer Edward Elcha. Charles Ford Williams Family Collection.

In December 1926, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters that was recently organized by A. Philip Randolph staged a huge carnival at the Manhattan Casino. The highlight was a bobbed-hair contest whose presiding judges were celebrity newsmen Lester Walton (writing for the New York World); Floyd Calvin (the Pittsburgh Courier); Lincoln Davis (the New York News); Benny Butler (the Interstate Tattler); and Romeo L. Dougherty (the New York Amsterdam News). “Among the three prizewinners we could not help but taking notice of the winner of the first prize, who happened to be Miss Gertrude Williams,” Dougherty wrote of her triumph among thirty women. “This young lady is the daughter of Chief Williams of the Grand Central Station, and perhaps it was appropriate that first honors should go to her. My dear, aside from wearing a bob one should know how to carry the head to get the real effect, and this young lady stepped out with an assurance which could not be denied.”40

By 1926 Gertrude Williams, noted for her signature bobbed hair, was a sought-after manicurist at a posh Harlem salon steps away from the Williams’s Strivers’ Row home. Charles Ford Williams Family Collection.

By now bobbed hair had become Gertrude’s signature, and this particular victory drew recognition beyond the black press. The New York Daily News ran a photograph of Gertrude flanked by her second-and third-place co-winners in the contest. “White papers heretofore have refrained from printing pictures of pretty colored girls except when they figured sensationally in the news,” the Courier remarked, regarding the coverage as a surprising first.41

Her carefree 1920s flapper persona aside, Gertrude was one of a growing number of independent enterprising women in Harlem’s beauty, fashion and event-planning professions. Being a manicurist also kept her in the loop of Harlem’s theatrical world and community network into the 1930s.

In 1924 James Williams was forty-six to his son Wesley’s twenty-seven. They had a tight-knit father-son relationship. Wesley was fanatically peripatetic: he even spoke of occasionally walking from his home in Williamsbridge to the firehouse on Broome Street, then back again. The Chief frequently enjoyed keeping pace with him for a few miles when his son headed for duty. Indeed, his son’s celebrity on the street was perhaps overtaking his own: that spring Harlemites read how Wesley had “thrillingly rescued a white woman and two children in a big fire” down on the Lower East Side.42

On October 19, Wesley picked his dad up at home on 138th Street, and they walked down St. Nicholas Avenue, enjoying the usual greetings from friends they passed by. The Chief probably never imagined he would see his son in action, but at around 118th Street they came upon a building ablaze. Nineteen-year-old William Thompson was hanging perilously from an open window. The crew extended an aerial ladder toward Thompson, and fireman Patrick Russell scrambled up. Meanwhile a thirty-foot hand ladder also raised a few feet away, and fireman Wesley Williams clambered up that one. Just as Wesley reached his ladder’s top rung, Thompson jumped to the nearby aerial ladder. Thompson clung momentarily, then started to collapse. “Williams, by a daring jump from his own ladder to the aerial, caught Thompson as he seemed ready to fall and carried him to safety,” the Times reported.43

Wesley’s typical heroism inspired other men in the ranks. Indeed Monk Johnson, former shortstop on the Red Caps baseball team, had named a newborn in the family Wesley Williams Johnson, after the Chief’s son the year before.44

Prohibition was in full swing at this time, and it of course profoundly influenced the Williams’s lives. Wesley had many social connections at Grand Central—aside from his father and three paternal Red Cap uncles, Joshua, Apollos, and Richard—and at Pennsylvania Station, where he himself had redcapped a few years before. “People, the dining car men and Pullman porters and all, wanted whiskey,” he later recalled. Wesley also “became very close with the Italians in the area—Lucianos, the Tony Rizzos, the Cusumanos—who were on my side because they hated the Irish.” Wesley’s Italian connections entrusted him with a truck and a driver, and a doctor’s prescription, which privileged him to withdraw cases of alcohol from a warehouse. With the diligence of Florence Nightingale, Wesley made runs up to Grand Central and Penn Station to unload his “medicinal” supplies of Green River, Canadian Club, or whatever whiskey. “I was making three, four five hundred dollars a day, which is a whole lotta money!”

One of Wesley’s regular customers was Conrad Immerman, the bootlegger owner of the new Harlem speakeasy Connie’s Inn, on Seventh Avenue and 131st Street. In a campaign to expose illegal “hooch joints” in Harlem, the New York Age often sized up tipsy patrons leaving the nightclub as evidence that liquor was amply flowing inside. Maybe the paper couldn’t yet tell how the club got its alcohol supply, but the Williamses might have known. While Wesley’s white co-workers at Engine 55 were still shunning him down on Broome Street, Immerman was welcoming him. He occasionally ordered twenty-five gallons of alcohol to “cut” into something else. “I was running with a truck up here and delivering it in full uniform,” Wesley said. “[Prohibition] was a stupid law.”45

Although Wesley got through Prohibition unscathed, his driver was less fortunate and was later deported back to Italy. The driver opened a restaurant outside Rome, where years later some white fire chiefs from New York on a family vacation happened to stop in to eat. Overhearing them, the Italian restaurant owner asked if maybe they knew “a color fella name a Wesley Williams?” What a small world, because sure they knew Wesley! Or so they thought. “Boy,” the Italian guy told them, “he was the biggest bootlegger down there!”46

Despite Williams’s subordinate status at Grand Central, his recurring contact with some travelers often gave rise to mutually profound interpersonal relationships. He got to know many young people this way, often students returning home on summer vacation from private schools: their headmasters or parents or servants wired to apprise him in advance of their scheduled arrival at the terminal, and he shepherded them from their train and into a taxi home. He watched out for former Vermont governor Edward C. Smith’s grandchildren this way, as he had once watched out for their mother when she was a young girl. Julian Street, the novelist and humorist, had an invalid niece who frequently visited the city: she would only have “Chief Jim” lift her out of the car into her wheelchair. It touched him and also thrilled him when one day she walked into the terminal of her own accord. Through her, Williams formed a close friendship with Street and his son, Julian Street, Jr., a reporter. And sometimes a few young overpartied sons of celebrities needed to borrow cash from him to get back home.

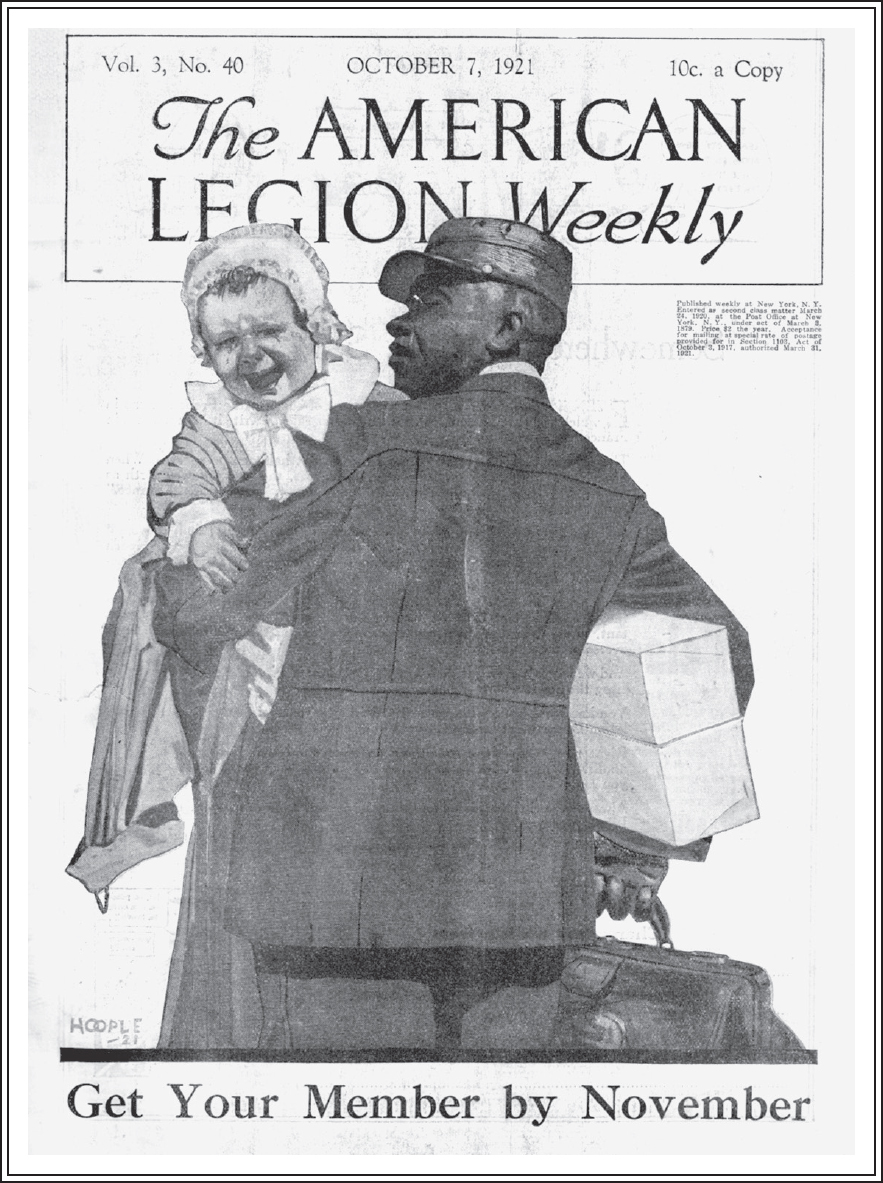

A 1921 magazine cover depicts a Red Cap porter, typically charged with all manner of a traveler’s bundles—even a cranky toddler. Illustration by William Clifford Hoople, American Legion Weekly, October 7, 1921.

Williams got to know Anne Stillman through such contacts. The daughter of Anne Urquhart Potter and financier James A. Stillman was about his own daughter Gertrude’s age. On October 18, 1924, he boarded a train to Westchester, where he would go on to Mondanne, the Stillman family estate in Pleasantville. Chief Williams was “among the few friends” invited to the wedding of heiress Anne Stillman to financier Henry P. Davison of J. P. Morgan, where her father worked.

“It became known today,” reported the Daily Argus, “that Miss Stillman had invited George [sic] Williams, the porter, to be present at the ceremony because of the attentive courtesies he has shown her during the long period she has passed through the New York Depot in going to and from Pleasantville.”47 The New York Post also referred to him as George: “James H. Williams, more familiarly known as ‘George,’ head attendant at Grand Central Station, set out for Pleasantville today to attend the wedding of Miss Anne Stillman and H. P. Davison. He was a specially invited guest of Miss Stillman, whose baggage he has carried on numerous occasions. Williams is a Negro and has been at Grand Central for twenty years. He lives at 226 West 138th street.” If that didn’t just beat all, the paper threw in for good measure that another invited guest was John Cane, for many years the Stillman chauffeur.48 The condescension may have aimed to cut the eccentric Stillman household down to size as much as to put some uppity Negroes in their place.

Quite commonly, whites liberally referred to any sleeping car porter, Red Cap, or other black service worker as “George,” irrespective of whether they knew him personally. It was an age-old practice, assumed to date from the time when one of industrialist George Pullman’s new railroad sleeping cars carried the remains of assassinated President Abraham Lincoln from Washington, D.C., to Springfield, Illinois. Journeying through seven states and 180 cities, the stately and stylish train intrigued thousands of mourners along the funeral route. Pullman, who hastened to meet the expectations of middle-class luxury-seeking white passengers, had a surfeit of newly freed Negro men to provide obsequious service on his “hotel on wheels”—many called them “George’s boys.”

Later the blanket “George” moniker for black porters might have gained traction around 1903, when the New York Central’s General Passenger Agent George Daniels admitted Williams to Grand Central’s staff of white Red Caps he had organized earlier. By the time the new terminal opened in 1913, its use was widespread enough that lumber baron George W. Dulany founded the Society for the Prevention of Calling Sleeping Car Porters “George” (SPCSCPG). The sardonically named club aimed more to spare its white members the indignity of being taken for a mere porter than to promote racial justice—yet it oddly impacted all porters beneficially: in 1926 the Pullman company agreed to display the given name of the porter on duty in each car. It was said that of Pullman’s twelve thousand porters and waiters, “only 362 turned out to be named George.”

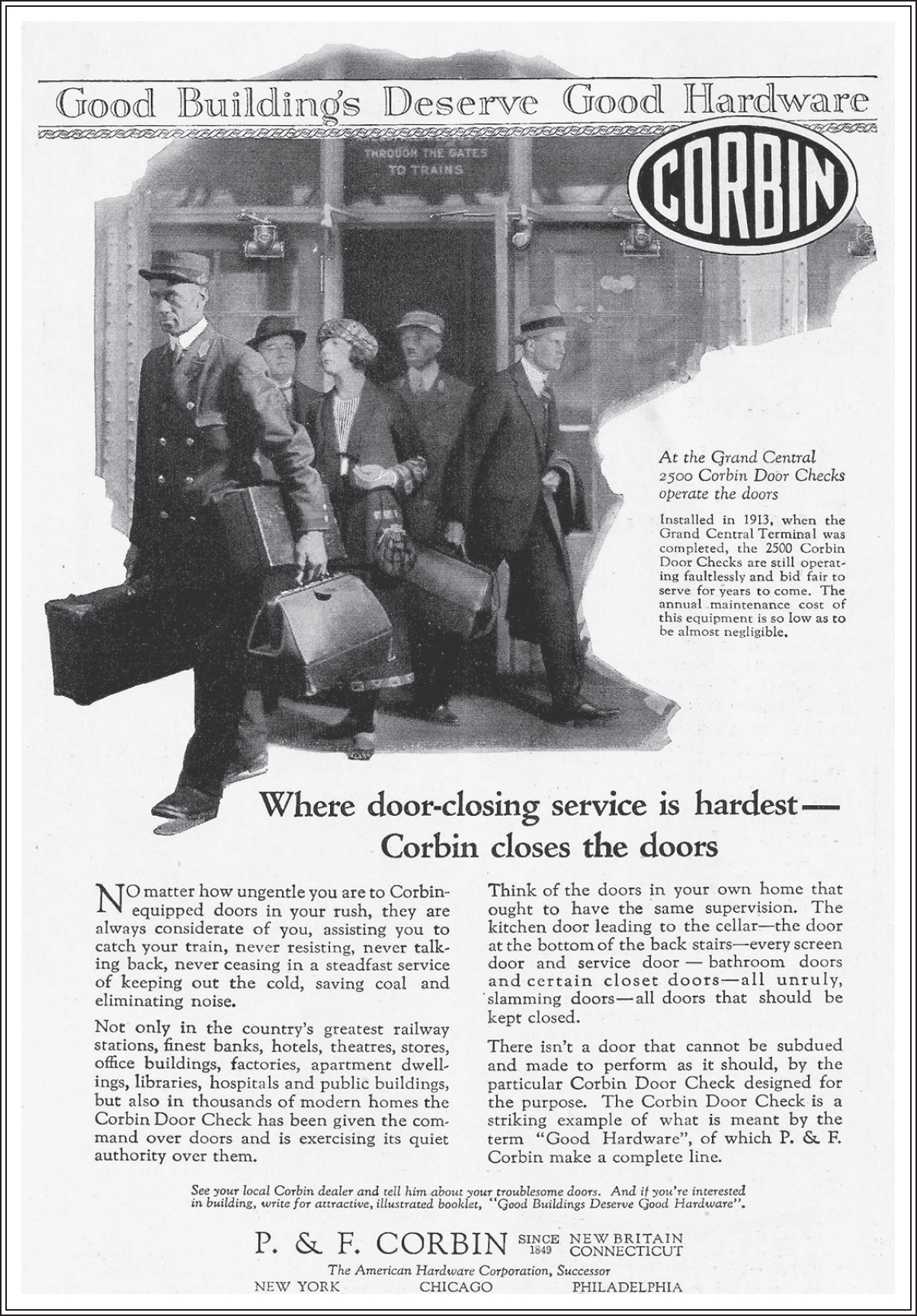

A 1922 advertisement for the Grand Central Terminal’s operative hardware evokes fluidity of passenger service through the conspicuous toil of the station’s Red Caps. Author’s collection.

Needless to say, many porters (including the rare few actually named George) hated it. “Tell you this, I have to come when these fellas yell for George,” a porter admitted, “but I don’t come with some such alacrity as I do for them that calls me just plain porter.”49 Perhaps snarking back at SPCSCPG, porters at Penn Station had organized a new union, it was said, with a chief objective of discouraging the traveling public from “calling every man who wears a red cap, ‘George.’”50

It seems doubtful that Anne Stillman addressed Chief Williams by anything but his real name. By their initiative and insistent dignity, Williams and other Red Caps frequently transcended traditional ethnic castes and economic stations.