CHAPTER 11

Moving to the Dunbar

One of the worst tragedies imaginable is an individual trained to do a specific thing and not in a position to do it.

—GEORGE S. SCHUYLER1

Despite the economic depression, Chief Williams still had his Harlem townhouse on West 138th Street. The U.S. Census taken in the spring of 1930 recorded its value as $30,000, higher than almost any other on Strivers’ Row. However, the deepening financial crisis induced him to sell, and sometime the next year he moved into a fairly new complex on Seventh Avenue and 149th Street popularly called the Dunbar, and later colloquially, “Celebrity House.”

The financier and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller, Jr., son of the Standard Oil co-founder, built the Paul Laurence Dunbar Apartments in 1927 as a quality residence for Negroes. The relatively unknown architect, Andrew J. Thomas, was keenly interested in using charitable and state funds for projects that would eradicate city slums. News of Rockefeller’s purchase of the Harlem ground for Negro cooperative housing attracted other philanthropic interests. “This is one of the most needed operations that I know of in the City,” Walter Stabler, comptroller for the Metropolitan Life Insurance company, wrote enthusiastically to Rockefeller, expressing the hope that the complex might obtain tax exemption toward offering a savings to tenants. “The colored people do not have a fair chance in this, as in many other ways. I know that congestion is very serious there and that they are living under conditions which are not sanitary or moral.”2 The walk-up cooperative complex was the first large-scale residential project of its kind in Manhattan and filled a full, irregularly oblong city block bounded by West 149th and West 150th streets, Seventh and Eighth avenues, and Macombs Place.

What to call Rockefeller’s utopian housing project aroused widespread interest. Such an unprecedented venture called for a distinctive name. Several individuals and institutions suggested names of distinguished blacks for the project. John D. Rockefeller thought the Abraham Lincoln Garden Apartments would be fitting, and specified distinct names for individual buildings: the Eighth Avenue building he called the Booker T. Washington; the Seventh Avenue building, the Frederick Douglass; the two 149th Street buildings would be the Paul Laurence Dunbar and the Alexander Pushkin; and the two 150th Street buildings, the Sojourner Truth and the Toussaint L’Ouverture.3

By February 1928, when the development opened, a single name had been decided upon for the entire full-block complex: the Paul Laurence Dunbar Apartments, after the esteemed African-American poet (1872–1906). With 512 units, the Dunbar could house over 2,000 tenants in suites varying from three to seven rooms. Sales prices ranged between $3,600 and $9,800, for which purchasers made a down payment of $50 per room and a monthly charge from $11.50 to $17.50 per room. In the papers, Williams would have read of the stern residency requirements of the Dunbar Apartments. Applicants to live in this Rockefeller housing experiment had to provide three solid references.4

The Dunbar’s all-black staff answered to Roscoe Conkling Bruce, a Phi Beta Kappa Harvard man who was formerly the assistant superintendent of colored schools in Washington, D.C. Bruce’s wife Clara Burrell Bruce, an honors law graduate from Boston University, was an assistant manager and legal adviser. “The sporting fraternity, daughters of joy, and the criminal element are not wanted in the Dunbar Apartments,” Bruce emphasized to a women’s city club. Some found it both sobering and risible that neighbors of one tenant—vexed by another’s impatience to just wait for the iceman—reported her for setting out a milk bottle on her windowsill. A writer’s observation that the Dunbar was inhabited by intellectuals piqued another’s curiosity. “We perused the honors list and failed to find a single undertaker,” he wrote. “Maybe the undertakers don’t care to bury intellectuals.”5 But despite some occasionally irresistible lampooning, the Dunbar Apartments experiment was taken seriously.

The Dunbar’s commercial spaces included a doctor’s suite, a dentist’s suite, and ten shops.6 One business that opened on April 17, 1928, broadcast the height of luxury, its name in gold letters emblazoning the windows of the prominent corner at Seventh Avenue and 149th Street: THE MADAM C. J. WALKER BEAUTY SALON NO.2. A secondary showplace to the company’s A’Lelia College, at 110 West 136th Street, the salon fulfilled its $10,000 investment. Three French dolls sat in the show windows, two of them black and one white, surrounded by Madame Walker hair preparations. A thousand visitors inspected the shop the first two days after it opened and found a plush interior. Light-colored mohair draperies with interwoven black fringe punctuated the color scheme of orchid green and orange amid wicker furniture. The floor was green inlaid linoleum. The eight booths were scientifically equipped with beauty apparatuses and products. In May, architect Thomas gave the city’s mayor a personal thirty-minute tour of the Dunbar: “Mayor James J. Walker himself spent 10 minutes by the clock inspecting [the beauty salon],” the Pittsburgh Courier gleefully reported, adding, “and remarked the place would do Park Avenue credit.”7 While Williams was not yet looking to move, he must have been taking it all in.

The most conspicuous commercial occupant of the cooperative complex was to be its “colored bank” component, at the corner of Eighth Avenue and 149th Street. The prospect had sparked considerable enthusiasm months earlier. Though Harlem’s celebrated bibliophile Arturo Schomburg personally recommended several black businessmen with “whole hearted interest in the establishing of such an institution,” none were heeded. Rockefeller chartered the Dunbar National Bank in September, under the direction of the Dunbar’s resident manager Roscoe Bruce—the rest of the board of directors being white.8

By 1931, given the Depression-troubled housing market, the columnist T. R. Poston found it ironic “that there were at least a dozen vacancies ushered into the Paul Lawrence [sic] Dunbar apartments with the new year—although the corporation speaks often of a waiting list that runs into the hundreds.”9

The Williamses appear to have moved there sometime in 1931. Regardless of the Dunbar’s prestige, it was as likely as not Gloria Williams, the Chief and Lucy’s granddaughter, who swayed their move to the apartment complex, whose amenities included accommodations for child care and recreation. Though the Williamses were not among the initial cooperative tenants before the crash, they were surely the kind of renting tenant that the selective Dunbar management was eager to cultivate.

The Williamses were indeed part of one of the most important experiments in improved housing conditions for low- to middle-income black workers. Years later, the Baltimore Afro-American would point to New York’s Dunbar as “unquestionably a precursor of the low-rent housing projects which have been built in cities all over the country through the United States Housing Authority and local housing authorities.”10 Unfortunately, the comforts of Williams’s new home were short-lived.

Considering that Lucy Williams was the wife and mother of a celebrity husband and children, she had long escaped the spotlight. Nevertheless, she was usually active, praised by friends as an attentive matron and hostess. On the afternoon of September 30, 1932, she was on a characteristically charitable errand, to visit a friend’s dying mother. But upon her arrival, she suddenly collapsed. Some speculated the shocking sight of her friend’s condition brought on a stroke. An ambulance came and returned her to her new home at the Dunbar. Someone called for Dr. James L. Wilson, a prominent physician and an old family friend: the Chief hired Wilson as a Red Cap when he was in medical school.

Lucy Williams died at home the next afternoon, Saturday, October 1, seven days shy of her fifty-first birthday, surrounded by her family.11 One can only surmise their disquiet and sorrow, their anguish being lost to history. Perhaps Dr. Wilson, who pronounced Lucy’s death as brought on by a cerebral hemorrhage, fought to conceal his own pain from them. Lucy’s service took place three days later at Grace Congregational Church on West 139th Street. Chief Williams sat with his five children: Gertrude, Pierre and Kay, who were living in the Dunbar; Wesley, who had stayed in the Bronx; and Roy, who was lodging in a place nearby. Of course James’s parents, Lucy’s sisters, and their grandchildren were present as well. Chief Williams was at once composed and undone: Lucy, with whom he had eloped in their teens, his constant companion, was gone. After thirty-five years of marriage, the Chief was now a widower.12

In the fall of 1932, the Rev. Richard Manuel Bolden decided to write a weekly series for the New York Age, profiling some of Harlem’s most outstanding race citizens. Bolden was a natural pick to write the series. Originally from North Carolina, he became pastor of Mother AME Zion Church when it was on West 89th Street. He had been spirited and sometimes controversial. He had spearheaded the church’s move to Harlem in 1914 and the same year set off a congregational schism when he refused to accept the bishop’s appointment to the Institutional Church at Yonkers. A clerical court tried and expelled him for “insubordination and conduct prejudicial to the peace and harmony of the Church,” and his subsequent expulsion prompted him and several followers to establish an independent church movement.13 “R.M.” Bolden was still one of Harlem’s most influential voices in matters both sacred and civic.

To debut the series, Bolden decided to feature his old friends James Williams and Jesse Battle. He had met them both some three decades earlier when his former classmate, the Rev. William D. Battle, asked him to look up his brother Jesse at Grand Central Terminal in New York, where he was working as a Red Cap. Bolden had tried to steer Battle toward the ministry, in vain. But after Bolden became pastor at Mother AME Zion, Battle joined the congregation. Bolden recalled it was about then that he, Elks attorney J. Frank Wheaton, and others induced Jesse Battle, “this big, husky fellow, to take an examination to become a member of the police force, the first Negro to make such an attempt.”

Battle had been able to study for and pass the exam while working at Grand Central, which moved Bolden. “My interest in Red Caps . . . has greatly increased since Jesse Battle became a policeman,” he wrote in the profile. Battle had gone on to earn subsequent promotions. Bolden perceived that race men could use a low-status job, such as a Red Cap, as a leg up toward achieving higher goals.

He also discovered his new appreciation for race men in influential positions, fraught with scrutiny and temptation, who chose to be of service to others—namely, Chief Williams: “He saw his duty clearly, and the performance of that duty, nobly and honorably, has resulted in a great number of Negro professional men realizing their life’s ambition. They now hold prominent, and in some cases indispensable, positions of service to their race and to mankind.”14

Being a Red Cap had been propitious. Wesley (once a Penn Station Red Cap) was his other case in point: “It is to the everlasting credit of Chief Williams that he raised a son to stalwart manhood, in whom he instilled the pride of accomplishment. That son is Lieutenant Wesley Williams, of the Fire Department of the City of New York, the first Negro to attain this honor.”15

When Wesley was promoted again some months later, Battle sent congratulations for his “very high rating on the Captains List in the Fire Department,” adding “kindest regards to your dear family and also your good father.”16 Others often congratulated his father directly: the noted pediatrician T. W. Kilmer (also a renowned portrait photographer whom Williams may have sat for) telegrammed: CHIEF WILLIAMS, CARE RED CAPS / GRAND CENTRAL STATION / CONGRATULATIONS ON WESLEYS ADVANCEMENT KINDEST REGARDS TO YOU BOTH / DR T W KILMER.17

Bolden valued that redcapping had enabled many Harlem men to make remarkable inroads into the middle class. Yet others noted that in fiscally dismal and societally prejudiced times, even established middle-class men relied on Red Cap jobs to sustain themselves. News columnist T. R. Poston wrote of a young Red Cap doctor’s journey to disillusionment in a poem, “Harlem Healer”:

Dr. So and So, M.D.

Dr. So and So, A.B.C.

Dr. So and So, X.Y.Z.

Office Hours, 11 to 3.

Harlem is young—

So are its doctors . . .

Gold lettered window pane,

Proud M.D. behind the name,

Office on the Avenue—

(Two months rent long overdue)—

Disdainful of the smaller town

Where needless Death always abounds.

For this he waged his six year fight—

“Doc” by day, “Redcap” by night.

Where do young Harlem doctors go when they die?

Ask the Pennsylvania Railroad!

Ask the New York Central!

Ask your White God!18

One could also ask Walter White, as many friends did, for assistance. The NAACP head might write in turn to Chief Williams for a favor, as he did in 1933: Dr. Guy Thomas was an old friend, now in New York, whose dental practice had collapsed in the Detroit banking crisis that year.

Dear Chief:

This will introduce Dr. Guy Thomas who has come to me to ask aid in that most difficult of tasks—finding employment.

Dr. Thomas has not only his wife and himself to support, but an eight-year-old daughter. I know how many appeals are made to you but if you can possibly give employment to Dr. Thomas I will be most grateful.

With cordial personal greetings, I am

Ever sincerely,

Walter White19

With a different objective, NAACP field secretary William Pickens wrote to introduce Helen Boardman, “the person who investigated the Mississippi Flood Control situation for us.” Boardman, a white former Red Cross relief worker and longtime NAACP staffer, had recently exposed a brutal Negro “peonage” system in a major federally funded works project. Her objective at Grand Central concerned the NAACP’s New York membership and financial campaign, for which Chief Williams was a known resource. “The members of your force have taken a good part in our previous efforts to support the Association in New York City,” Pickens wrote, hopeful Williams would rally their participation again.20

It’s unclear if Williams replied. Pickens followed up with a letter to another worker a week later, care of the stationmaster’s office (which oversaw the Red Caps), to confirm receipt of information about the NAACP’s Harlem campaign: “We would like to get the Redcaps and porters of Grand Central Station interested in our work,” Pickens wrote Rudolph Foster (possibly a black office worker), adding, “Kindly let me hear from you, and someday soon I hope to drop in to see you.”21 The field secretary might have been reaching out to a contact at random, perhaps on Williams’s recommendation, or maybe was just casting a wide net.

But the Chief might also have been preoccupied with a personal crisis: a year after losing his wife Lucy, his mother Lucy died. On November 19 she succumbed to a cerebral embolism, dying in her ground-floor tenement apartment at 19 West 131st Street. Lucy Ellen Spady Williams, the matriarch of fifteen children, was buried at the Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn. Sometime afterward the Chief’s sisters Ella and Lena moved their father in with them at the Colored Mission, directly across the street at 8 West 131st Street.

In late January 1934 Pickens invited the Chief to attend the NAACP’s twenty-fifth anniversary dinner on March 18, at International House on Riverside Drive. The association was also conducting a campaign called “A Penny for Every Negro,” striving to raise $120,000 by collecting 12 million pennies from that number of America’s black citizens. For this major campaign to mark the organization’s milestone anniversary, Pickens wanted to post uniformed girls with coin canisters and informational handouts at the terminal entrances on February 12—Lincoln’s and the NAACP’s shared birthday—to collect donations from whomever wished to contribute:

My dear Mr. Williams: . . .

An organization does not have a 25th anniversary but once during its existence. . . . Can you tell me how we can go about it—to secure the privilege of having some of our workers at the station for this one day? . . .

Very truly yours,

William Pickens22

Considering the earlier participation of Grand Central’s Red Caps during the Silent Protest Parade, one could see what value the NAACP placed on them in its mission to address the country’s race crisis. The terminal’s conspicuously trunk-laden black men were a deceptively learned bunch of able communicators and masters of discretion. “It looks awfully easy, toting baggage in and out of the train platforms but it isn’t,” Chief Williams once said. “It takes a man with tact and tact is a rare quality, I’ll tell the world.”23 Tact, indeed, was the operative, relevant lesson to the utility of portering that he had no doubt taught his children. Indeed, it was a lesson he now had occasion to see being passed on to his grandchildren. Wesley, to gain summer jobs for his teenage boys, James and Charles, was finessing their introduction to Penn Station by way of the company president, William Atterbury: “Mr. President I once had the honor of handling your luggage, but that was way back in 1916. Now would you be so kind as to give my boys employment as Red Cap Porters, thereby giving them the chance to learn discipline, diplomacy and the ability to give service to the Public under the most trying conditions, just as I learnt to do?”24

President Atterbury promptly replied that he was “doubtful . . . if much encouragement can be given them at this time,” the midst of the Depression. But perhaps the official warmed to the idea, for which he expressed gratification, that Wesley attributed some of the achievement in the New York fire department to his turn as a Penn Station Red Cap. Atterbury complimented Wesley on his “splendid record” on the force, and, despite his initial doubts, he influenced a favorable outcome for Wesley’s request through the Penn Railroad channels.

Pursuing his mission “to help the young man who is trying to help himself,” Chief Williams might well have authored the image of the erudite porter, in contrast to the dull, biddable attendant sometimes caricatured by blacks and whites alike. Years before, the satirist Bert Williams had portrayed a hapless, illiterate Red Cap assigned to staff the Grand Central information booth, hilariously rendering a travel system dependent upon infallible directions and timetables into a house of cards. But Chief Williams strove fervently to correct this impression for years.

The real Grand Central Red Caps were hardly unread. “I think I am safe in saying,” the Chief observed, “that we give work to more men who are going through college than any other department of the Terminal.”25 They were a paradox: so ubiquitous as to be taken for granted, yet so overqualified for their duties as to be curiosities. In fact, their curious learnedness was frequently the grist of magazine articles nationwide: a writer in The New Yorker counted “five graduate students (one an honor student at Harvard), several lawyers, singers, teachers of music, and other persons of some erudition and attainment” among the men staffing Sugar Hill (the terminal’s Vanderbilt Avenue taxi entrance).26

Student Red Cap was a familiar term in casual social parlance, as when writer Dorothy West described an eclectic Prohibition-era cocktail gathering of “two Negro government officials, two librarians, a judge’s daughter, a student-red-cap, a Communist organizer, an artist, an actress.”27 Writing in the short-lived political newsmagazine Ken in 1938, writer Ann Ford’s provocatively titled article, “Ph.D. Carries Your Bags,” emphasized the paradox that typically 40 percent of Red Caps (about every third man in a regiment of hundreds) had college training. “The white man who works as a porter can do nothing else, as a rule,” she wrote; “the Negro almost invariably can do something else but can’t get it to do.”28

For decades images of black Red Cap porters toting baggage, such as a 1921 Kuppenheimer clothing ad by noted illustrator J.C. Leyendecker, or an urbane 1934 New Yorker magazine cover by Rea Irvin, were ubiquitous in the visual culture of American railroad travel. Ephemera advertisement; Molly Rea/Molly Rea Trust, Christie Fernandez and Marie Noehren.

Sadly, this was old news. Chief Williams had commented nearly two decades earlier, “We have a fine class of men here. The men who carry your suitcases are not mere porters. They are artists in their line of work. Why, we have several law students, several dentists and at least one doctor and a preacher in the organization. As for writers and editors, we have any number of them. Only a short time ago one of our men, John Robinson, resigned to become editor of a newspaper. I’m telling you this because I want you to know that it takes education to ‘carry on’ here at the Grand Central.”29

Among the numerous educated Red Caps was John Robinson (Williams’s earliest profiler in 1909), who went on to manage the Amsterdam News; he was also president of St. Mark’s Lyceum and active in the antilynching movement. There was Dr. Guy Thomas, Walter White’s dentist friend from Detroit, and Rev. John M. Coleman, who in 1933 became rector of Brooklyn St. Philip’s Episcopal Church; in 1946 Mayor O’Dwyer would appoint him to the city’s Board of Higher Education, the first black board member. Also Emanuel Kline, onetime Red Cap, was a police officer who in 1947 would be promoted to captain, attaining another “first” for a black of that rank. Paul Robeson, the internationally famous singer and football all-American, redcapped at Grand Central to pay for law school at New York University. There was Raymond Pace Alexander, a noted Philadelphia judge and civil rights leader. And Antonio Maceo Smith would become an advertising and insurance executive and help establish the NAACP in Dallas, Texas.

These were just some of the many notable achievers from the ranks and ramps of Grand Central. Relatively few might boast an intimate friendship with Chief Williams, but all would likely acknowledge him as helping them attain prominence. Writer George Schuyler observed with wry grimness: “Turn a machine gun on a crowd of red caps at a big railroad terminal and you would slaughter a score or more of Bachelors of Arts, Doctors of Law, Doctors of Medicine, Doctors of Dental Surgery, etc.”30

Williams himself had not gone past grade school, but he was fond of likening Grand Central to an institution of higher learning, “The University of Human Nature”: he was its president, his dozen or so captains its professors, and the hundreds of Red Caps its student body.

All became skilled at a peculiar diplomacy that strained physicality and equability: “In good times or bad, the Red Cap greets the patron. He knows a little bit of everything. They must be walking booths of information. The questions he is asked vary from the time of departure of the Trans-Atlantic steamers to the time the baseball game begins, and how far is the nearest eating place. He must look out for crooks and pickpockets who infest the city Terminal. He has to walk about ten miles a day in all sorts of weather. He has to keep his temper. He must be a good deal of a mind reader.”31

A mind-reading porter was indeed one for the books.

Chief Williams appears to have been the prototype for a fictional chief of Grand Central’s Red Caps. In the short story “A Woman with a Mission” by Arna Bontemps, he is Ezra High,—“an old West Indian mulatto.” In the story, Mrs. Eulalie Rainwater, a white dowager philanthropist, is on a Grand Central platform anxiously awaiting her train for Larchmont. Suddenly a silvery tenor voice emanates from the Red Cap before her: the porter is nonchalantly singing Schubert’s “Du bist die Ruh,” in the original German! She is quite certain that she has just “discovered the strange genius” of a Negro artist. She duly informs Leander Holly, her “treasure from the jungle,” that she knows his boss, Ezra High. “Will you tell him Mrs. Rainwater said to telephone her tonight?” she asks. Holly does so when he encounters the chief:

“Did you see her?” [the Chief] asked. . . .

“See her!. . . . She heard me and asked my number. Then she told me to have you call her tonight.”

“She’ll see you through if she takes a fancy to you,” the chief said. “That’s all she’s been doing for thirty years. I worked for her husband. . . . And I mean he left her plenty. She’s sponsored hundreds of young college folks. This Negro fever is something new, though. . . .”

“Lordy, it ain’t true,” Leander said. . . .”You don’t mean she might see me through the conservatory—Music lessons and all that?”

“She always allowed the others about two hundred a month outside of extras, trips, presents, and whatnot.”

Leander put his hand on the old fellow’s shoulder.

“I can’t tote no more leather today, chief. I got castles to build.”

That night the plot was completed, and the next evening Leander went to Larchmont to sing for Mrs. Rainwater.32

Bontemps’s characters point to real-life personalities. Leander Holly evokes the Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes, while Mrs. Rainwater suggests Charlotte Osgood Mason, Hughes’s generous patron. Mrs. Rainwater’s nemesis, the “degraded dilettante” Tisdale, suggests Carl Van Vechten, a progenitor of the white “Negro fever” or “Harlemania” that surged and eddied over the black capital in the 1920s and early ’30s. As for Chief High, he has an intuitive grasp of certain commuters’ personalities, whims, and routines—attributes inherent in the real Chief Williams.

It was Williams’s well-known promotion of racial uplift that had inspired Reverend Bolden to launch his Harlem profile series, and Williams’s scores of Red Caps seemed to attest to the job’s value. The journalist and politician Earl Brown, an alum of both the Grand Central University and the actual Harvard University, would later recall, “Only because the Chief had a big heart and was proud of his race were hundreds of young colored men able to go through college.”33

In January 1935, the film critic Archer Winsten wrote about famous people of the race who had lived, or still lived, in the Dunbar Apartments.34 Dr. Du Bois, then heading Atlanta University’s sociology department, lived in a fifth-floor walk-up apartment with his wife, daughter, and granddaughter, the same apartment he had moved into when Rockefeller opened the project. Bill Robinson lived there with his wife, Fannie, purportedly “one of the cleverest women in Harlem, financially speaking.” Matthew A. Henson, a U.S. Customs House official, was most famous as the black explorer who twenty-six years before had trekked with Admiral Peary—“He walked while Peary, on account of amputated toes, rode”—to discover the North Pole.

Lester Walton lived there, of course. So did twenty-eight-year-old E. Simms Campbell, the rare black cartoonist and illustrator for Esquire, The New Yorker, and other slick magazines. In a photograph, he nestled cozily on his pale green leather couch among his “folding bar and severely modern furniture,” looking every bit the picture of rising success. His hilarious, recently published “Night-Club Map of Harlem” was almost instantly iconic. His artistic forte was in the genre of “good girl art,” as he adhered to the magazine world’s requirement of drawing skimpily clad white women. Yet, Campbell was said to have insisted upon giving work to black models; one wonders how readily white models would have availed themselves as subjects for a black artist. And in yet another celebrity apartment, Winsten noted Chief Williams of the Grand Central Red Caps and father of Wesley Williams, “the only Negro fire captain in New York.”

The Dunbar’s attentively tidy inner court exuded a pride of place with horticultural touches “ranging from big bushes to little trees.” Parents could mind their kids in a central playground and nursery. “There are no benches where people might sit and mar the effect,” Winsten wrote. But the inner court, if rarified, likely felt reassuring to Williams and his neighbors during Harlem’s sudden turmoil a couple of months later.

The housing market’s downward spiral into the sinkhole of the Great Depression precipitated Harlem’s decline. A volatile climate arose that exploded into the Harlem Riot of 1935. On March 19, 1935, a rumor spread that employees at S. H. Kress, a five-and-dime store on 125th Street, had killed a boy for shoplifting a penknife or a bag of jelly beans. The rumor was potent enough to set people off. The riot involved 3,000 to 5,000 people. For about twelve hours, police wove through the district in radio cars, and emergency trucks emerged with riot guns, gear and tear gas. Harlem appeared to be a battlefield. Whatever the Harlem Renaissance had promised, the unrest seemed a manifestation of its deferral.

But the rumor that had set off the riot was unfounded: “A colored boy, a nickel penknife and a screaming woman were no more the cause of the Harlem uprising in 1935, than was a shipload of tea in the Boston harbor, in 1773, the cause of the Revolutionary War,” wrote educator and activist Nannie Burroughs in the Baltimore Afro-American. “An unknown boy was simply the match,” while “a frightened woman’s screams lighted it and threw it into the magazine of powder, and Harlem blew up.”35

To investigate the cause of the Harlem riot, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia appointed a biracial commission—whose members included the Chief’s acquaintances, Dr. Charles H. Roberts and attorney Eunice Hunton Carter. The unprecedented commission pointed out underlying social and economic conditions, urging that racial discrimination in jobs, education, recreation, and hospital staffing be outlawed. It advocated reforms in the processing of citizens’ complaints against police. But charges that La Guardia suppressed his own commission’s analysis—which surfaced when the Amsterdam News published the report more than a year later—compounded public frustration.36

The Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, of Abyssinian Baptist Church, identified the fundamental cause of the riot as the continued exploitation of blacks “as regards wages, jobs, working conditions.” “Think of all the milk used in Harlem, yet not one bottle of it is delivered by Negroes,” he said. “We see our boys and girls come out of college, well-trained, compelled to go on relief or work as red caps.” The pastor’s comment was particularly apt: almost a decade and a half earlier, Williams had hired Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., as a Red Cap.37

After much pain and ruin, the Harlem Riot of 1935 did lead to something optimistic. In 1937 the Harlem River Houses were constructed a block from the Dunbar Apartments at West 151st Street, the country’s first federally funded housing project. From an old wound had come the promise of a new deal.

Barely was the year 1935 under way than far-flung conflicts addled the local mood. Chief Williams’s friend, the blues singer Alberta Hunter, back home from a tour in Europe, warned fellow black performers that Hitlerite sentiments were feverishly agitating race prejudice abroad.38 And under dictator Benito Mussolini, fascist Italy was poised to invade the black Ethiopian kingdom, fueling whatever latent spark of American black-versus-white animus that was still left to ignite. Under these circumstances, Black America longed for another Jack Johnson, for a new hero. It seemed to find one in Joe Louis, “Black Dynamite,” a rising Negro boxing star who was training for a much-anticipated match against the Italian boxer Primo Carnera, conveniently derided as “Mussolini’s Boy.”

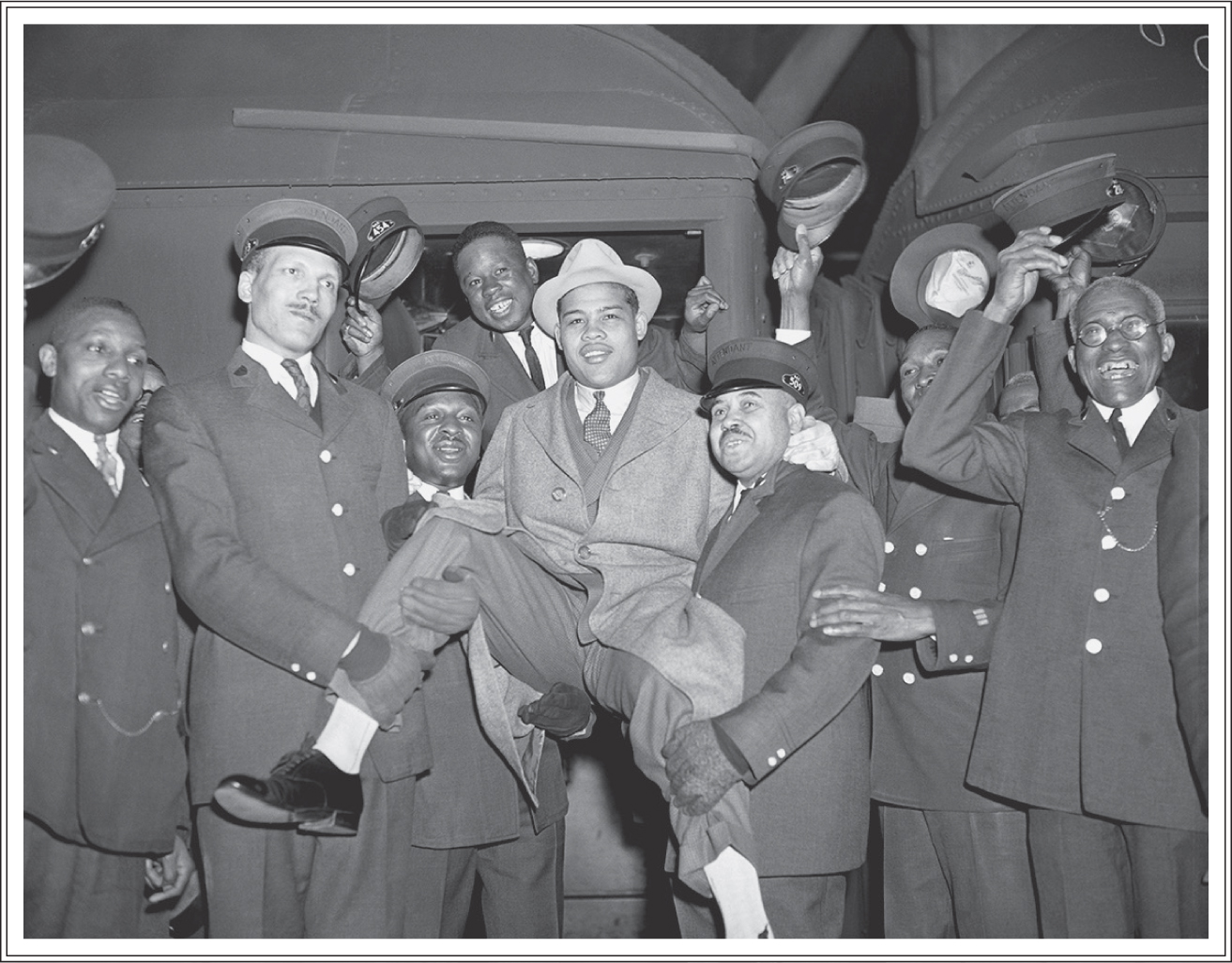

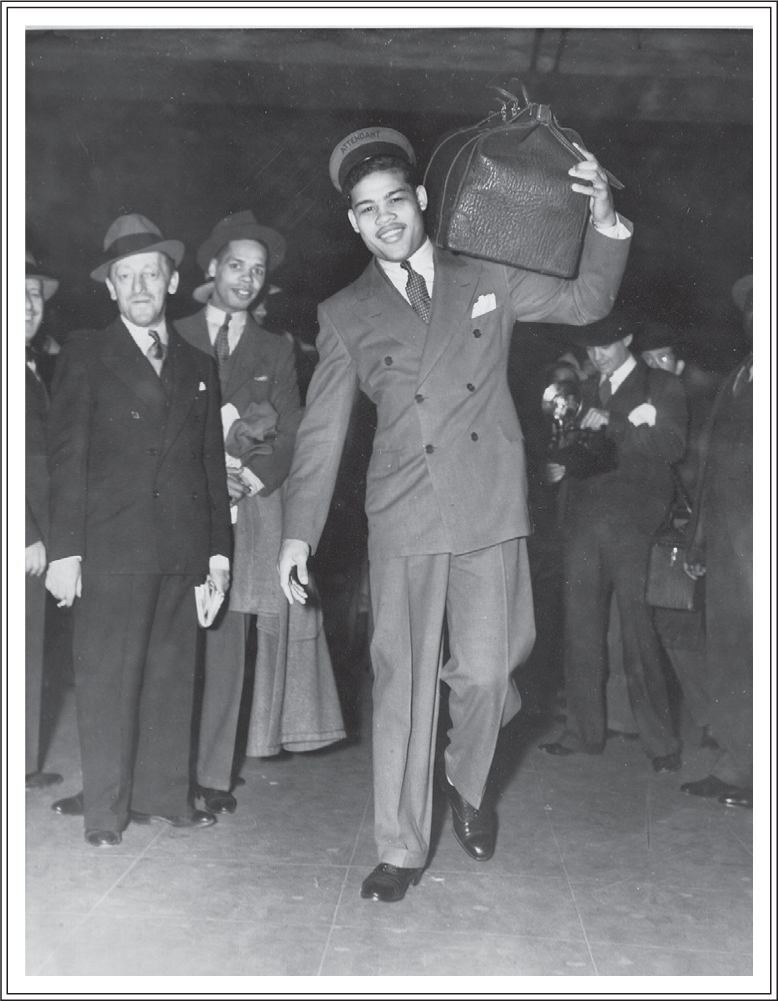

On May 15, 1935, two days after his twenty-first birthday, Joe Louis arrived from Detroit at Grand Central, “totally unprepared for the admiration of the colored red caps who clustered about him,” NAACP leader Roy Wilkins would later recall.39 He stepped off the train sharply dressed in a three-piece suit, necktie, overcoat, and fedora. No sooner did he appear than a dozen of Williams’s porters rushed him and exuberantly raised him aloft to their shoulders. Once they set him back down, he gamely swapped his fedora for a crimson cap, then heaved his bulging leather suitcase to his shoulder. The crowd cheered as he “smashed his own baggage” for press photographers. The good fun warmed up onlookers for the coming battle, which would ultimately benefit the New York Milk Fund, a charity established by Mrs. William Randolph Hearst.

On June 25 at Yankee Stadium, Louis’s powerful right knocked out Carnera in the sixth round, making him the new heavyweight champion of the world. As Louis subsequently became a frequent commuter on the 20th Century Limited, his friendship with Chief Williams blossomed.

On May 15, 1935, Red Caps exuberantly lifted twenty-one-year-old Joe Louis aloft as he detrained at Grand Central, and the prizefighter gamely effected the role of a Red Cap “smashing his own baggage.” Bettman Archives/Getty Images; ACME Press Photo.

Unlike Joe Louis, the Chief encountered other heroes who were less inspiring than intriguing. After Booker T. Washington died in 1915, Robert R. Moton took up the reins of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama and served as president until his retirement in 1935. On April 7 the school’s trustees elected his successor, Dr. Frederick Douglass Patterson, dean of the agriculture department. His installation was a double ceremony: Tuskegee’s new head also married the president emeritus’s daughter.40

But during that transition, a certain Red Cap at New York’s Grand Central Terminal suddenly felt “imbued with the spirit of the founder of Tuskegee” and claimed to newspapers to be the school’s new leader. He even presented a business card: “Tuskegee Institute, Tuskegee, Alabama; EUGENE H. MOORMAN, President.”41

At first no one questioned Moorman’s claim. After all, Red Cap porters were often remarked to be deceptively worldly in light of their humble vocation—one from Penn Station had recently won a New York Assembly seat. Or perhaps Moorman’s claim was so quintessentially American in its improbability—like something out of Horatio Alger, or akin to Booker T’s own Up from Slavery saga—as to make it worth egging on to pass the time. When informed of the fact that Tuskegee had just installed its new director, Moorman was magnanimous: Dr. Patterson should carry on as acting president until he was “able to go down and take over my new duties.”

By reputation, Chief Williams did not suffer fools gladly, but neither was he likely to turn one out to starve. Just how to confront Moorman gave him reasonable cause for concern. How had he not sensed that this young fellow was odd and a potential source of trouble? Papers often reiterated Williams’s words that a Red Cap needed a résumé five years deep to get hired. Would being too harsh on Moorman throw his own judgment into a bad light? Some co-workers described Moorman as “nice . . . studious, but a little queer.” Checking the reckless behavior of someone who knew better was one thing, but Moorman seemed bona-fide touched. The Chief could picture his name on the silver Williams Cup tennis trophy—of which Tuskegee was the first guardian—tarnishing like copper. In the end, the Chief dismissed the eccentric Red Cap genially as “harmless, but something of a nut.”42

In mid-summer, President Patterson wrote to Dr. Du Bois to assure him that Moorman, who had written to the latter, was “a mental defective.”43 That became the official consensus when Moorman, en route to his imagined presidential errand, was confined to a mental hospital in Baltimore. In the end neither Dr. Patterson nor Chief Williams was much affected, though Moorman’s fixation wavered little over the passing decades. In 1967 his enduring fidelity to Booker T. Washington prompted his avowal in a letter to the Baltimore Sun, “I shall make an effort to revive a great educator’s dream of peace and harmony between the races.”44 Which actually was one of the more wholesome delusions of the time.

In light of the Moorman distraction, Chief Williams had a number of family concerns that demanded his attention. On a sad note, on April 23, 1935, his son James Leroy, or Roy, died—his granddaughter Gloria’s father. The nature of their relationship is not clear, nor how he learned the news of the thirty-three-year-old’s death. But his son was still working for the railroad, most recently as a car cleaner, and whether it was at Grand Central or Penn Station, any news of import would likely reach the Chief in a timely manner. Roy was also buried at Woodlawn in the Bronx, though not with his forsaken wife, Lula.

Nearly two years earlier, in June 1933, the Chief changed his apartment at the Dunbar for another one, due to Lucy’s death.45 And by summer of this year, he finally sold his house on Strivers’ Row. The house, valued at $30,000 five years before, was now “assessed at $12,800” when he sold it to the Harlem Center of the Rosicrucian Anthroposophical League, a spiritual group founded in 1932 by astrologer and occultist Samuel Richard Parchment.46

A few months later Chief Williams acquired a son-in-law: on July 29, 1935, his daughter Gertrude married Leroi T. Jennings.47 The newlyweds—she a manicurist, he a government employee—were celebrated with a modest dinner party in the home of Harlem friends. Some surely wondered if Gertrude—given her beauty, charm, influential connections, and performing skills—hadn’t missed her calling. Chief Williams himself might have wondered if he had not missed his own.