CHAPTER 12

Organized Labor Pains

People will never know the troubles of a red cap unless they grab a bag and carry it themselves.

—WILLARD S. TOWNSEND, 19391

On June 15, 1938, the New York Central inaugurated a faster, sixteen-hour run from New York to Chicago. At six p.m., movie star James Cagney and other passengers boarded the new streamlined 20th Century Limited from Tracks 36 and 37, as the Chief’s twelve-piece Grand Central Red Cap Orchestra performed a swing fanfare to set the tone of their grand departure.2 The Red Cap musicians continued to have a palpable impact on the traveling experience. Perhaps even informing white musician Mary Lee Read’s regular live organ performances in the terminal: “What they will play on that Grand Central Terminal organ is troubling the program makers,” Franklin P. Adams, a humorist of the storied Algonquin Round Table, quipped. “Well, there might be . . . ‘When That Midnight Choo-Choo Leaves for South Norwalk’ . . . and ‘I’ve Been Riding’ on the Railroad.’ Not to add, ‘The Pullman Porters’ Ball.’”3

On the morning of May 11, 1938, Williams met the 20th Century Limited as usual. It was one of his routine formalities, as there were almost always celebrities or VIPs arriving—some regular, some new. Back in February, he had made a bit of small talk on the platform with Paul Whiteman and his wife, Margaret; the tall bandleader likely knew of the Chief’s enthusiasm for music, as Whiteman’s band and the Red Cap Orchestra or Quartet often appeared in the same radio columns. That same week a rising teenage singing star stepped off the Century as if the terminal were a Hollywood movie set: a baby grand and an accompanist materialized, not to mention half a dozen of the Chief’s porters who knew a thing or two about spontaneous jam sessions. Fifteen-year-old Judy Garland sat atop that piano, flanked by a melodious Red Cap chorus, to the delight of lucky passersby.

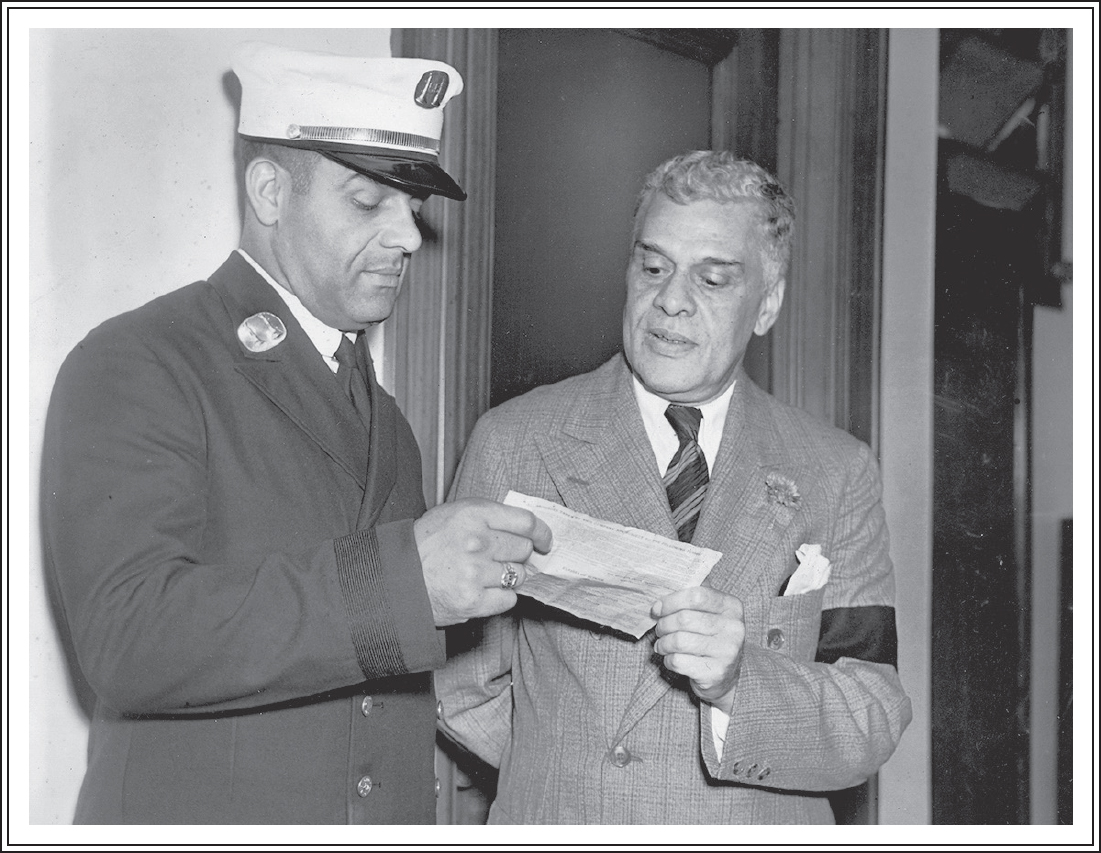

But on this day, Chief Williams beamed as his friend Joe Louis, the world heavyweight boxing champ, once again appeared in the Century’s door and stepped across the gap from the train. This time he was dressed casually in sports clothes and cap.4 He locked the Chief’s handshake. The two men were well acquainted by now, their friendship plain as they walked the length of the red and gray carpet together. Louis chatted loosely about being back in New York to sign up to fight Max Schmeling at Yankee Stadium on June 22.

On February 2, 1938, Chief Williams greeted bandleader Paul Whiteman and his wife, Margaret, detraining from the 20th Century Limited—the same radio columns encapsulated the two men’s shared musical interests. AP Photo Archives.

On February 7, 1938, a feat of pretended spontaneity treated Grand Central passersby to Hollywood starlet Judy Garland jamming with half a dozen singing Red Caps. Bettman Archives/Getty Images.

For his part, the Chief effused about Wesley’s promotion to fire department battalion chief, the first Negro of that rank in the country. Though Louis had probably already heard about Wesley’s promotion—newspapers across the country had been reporting it for weeks—Williams surely relished sharing the news with the boxer firsthand.

Wesley may have been the one to cinch his father’s easy rapport with Louis, in the three years since the boxer’s 1935 Carnera fight. Although Wesley was nearly seventeen years Louis’s senior, his civil service uniform concealed a kinetic athlete’s body. As a rookie fireman in the 1920s, he had won numerous municipal boxing tournaments, including the amateurs’ heavyweight championship title two years in a row. Even now, in his early thirties, Wesley had recently impressed crowds at a Harlem Y weightlifting exhibition as “the man whose physique is the wonder and admiration of the whole metropolis.”5 The Chief’s years were advancing—he was almost sixty—but Wesley’s avid athletic interests naturally gave him and Joe Louis some common ground for conversation.

Other news the Chief had to share with Louis was about their mutual friend, the dancer Bill Robinson. It’s not clear to what degree Williams and Robinson socialized with each other, but they both lived in the Dunbar, and Robinson’s brother Percy was one of the principal Red Cap musicians.

The Chief’s news was that Robinson had opened an exclusive members-only supper club, with bandleader Don Redman and others. The Mimo Professional Club was in the basement of the old Lafayette Theatre on Seventh Avenue, but it was no dive: it was $40,000 worth of members-only swank. Williams could have described for Louis how, in an anteroom two flights down, a steward checked membership cards, or letters of recommendation, before granting admission. When you stepped into the hall, the walls and ceilings exploded into florid accents of silver and gold against buff backgrounds. The menu offered Chinese as well as American food, from eleven o’clock at night until four in the morning. There was a central dance floor, but this was no cabaret, with floor shows and featured vocalists: members themselves provided the music, impromptu, “usually the work of some nimble-fingered piano playing guest.”6

By May 11, 1938, Chief Williams and Joe Louis had become close when the 20th Century Limited brought the heavyweight champ to New York to sign up for an imminent bout with Max Schmeling. AP Photo Archives.

The Chief was a member and a fairly regular fixture at the Mimo, often at the center of the club’s vibrant social scene: “After work each day he arrives at the Club Mimo about 5, lingers through the dinner hour and talks with the manager, Mal Frazier. Everybody knows [Chief Williams], so he is constantly speaking to patrons coming and going. Sometimes part of his large family joins him at dinner.”7

Inasmuch as Joe Louis had come to feel like family, it would have been no surprise if the Chief indulged a meddlesome notion of the boxer as a son-in-law—a match for his beloved Kay. Since 1935 Chief Williams’s daughter Kay, his youngest child, had been involved in an on-again off-again relationship with a fellow named Harold Bundick. It was highly publicized: gossip columns would report on rumors of his infidelity, then announce the couple’s engagement, then announce their separation weeks later. But finally on Sunday, July 10, 1938, Kay and Harold were married at St. Mark’s Methodist Episcopal Church. Williams greeted the guests, a moderate gathering of immediate family members and close friends from both sides. Kay was lovely, sporting an informal white afternoon dress with a gathered waist that buttoned primly below her throat, delicate white gloves, and a giant flower corsage. A wide-brimmed hat haloed her bright face. Her sister Gertrude was her matron of honor, complementing her in a pale blue dress, gloves, and smart disk of a hat. Harold, the groom, and Ballard Swann, his best man (and a Red Cap), wore dark suits. No doubt to Kay’s disappointment, Wesley was absent—her celebrity big brother was slated to be promoted to battalion chief—but a wedding announcement noted her sister-in-law Margaret. Chief Williams’s older brother Charles and his wife Jennie came.8 The Chief looked dapper in a light double-breasted suit, his usual pocket square and boutonniere, and a straw hat. His left arm bore a mourning band.

The couple’s wedded bliss was short-lived. “By now Harold Bundick and Kay Williams must be used to being ‘Mr. and Mrs.,’” an item read less than a month after their wedding. “Just heard about a very fine friend of ours being on the ‘Y’ boat ride with someone other than the wife.” Apparently, they reconciled, but two years later he was living at the 135th Street YMCA. “And have you heard of the rift between the Hal (Kay Williams) Bundicks,” the columnist asked rhetorically, “which by the way reminds us that Kay came to the affair Friday night accompanied by A—T—.”9 Alas, prying eyes were relentless.

On July 28, 1938, Chief Williams went downtown to attend Wesley’s promotion ceremony. In the Municipal Building, at 1 Centre Street, near City Hall, his son made history by being installed as battalion chief—the first and only black officer of any rank on the force. The new position came with a healthy annual salary of $5,300 (or about $95,000 in 2018). But the ceremony was also bittersweet. This honored occasion for the Chief, a moniker that his son now rightly owned as well, must surely have turned his thoughts to his own father. John Wesley Williams, who had proudly stood beside Mayor John Hylan when his grandson was commended at City Hall some years before, was now slowing down at eighty-seven. One can only surmise the Chief’s happiness that his father got to see his grandson Wesley make history again, to see his granddaughter Kay married, and to see their cousin Lloyd, Ella’s boy, become the first black teacher hired by the Detroit public school system.

Exactly five years to the day after his mother Lucy’s death, the Chief’s father went under a doctor’s care. He underwent prostatic surgery and endured a monthlong illness, then on December 19, 1938, he succumbed. He died at the Colored Mission across the street, which Williams’s sisters Ella and Lena still ran. Though the Chief had long been the family figurehead, he knew his place as he looked now upon his lifeless father, who had once extracted himself from bondage by his own volition, then wove his own inextricable lineage into the world. John Wesley Williams, the patriarch of five generations of Williamses, was surrounded by his family, who would bear him to rejoin his Lucy at the Evergreens in Brooklyn.

On July 28, 1938, the Chief saw his son Wesley become the first black officer promoted to Battalion Chief of New York City’s Fire Department. Press photo.

The advance of the Great Depression through the 1930s steadily polarized labor and management. The desperate economic times fueled union consciousness, notably among railroad workers. A decade earlier A. Philip Randolph had organized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL). In 1937 Chicagoan Willard S. Townsend similarly founded the International Brotherhood of Red Caps (IBRC), as labor tensions increased among the station porters across the country. Early the following year a bellicose letter from an anonymous “Negro Red Cap, at the Grand Central Station,” railed about wages and working conditions: “Together with the Red Caps throughout the country we have planned to hold a Red Caps’ Convention in Chicago,” he wrote to the Daily Worker, a Communist Party newspaper. “And we plan to come out of that Convention in a two-fisted fighting mood.”10 Similarly echoing the critical articles in The Messenger a decade earlier, the angry missive neither named nor alluded to Chief Williams, who did not respond to it—at least not directly.

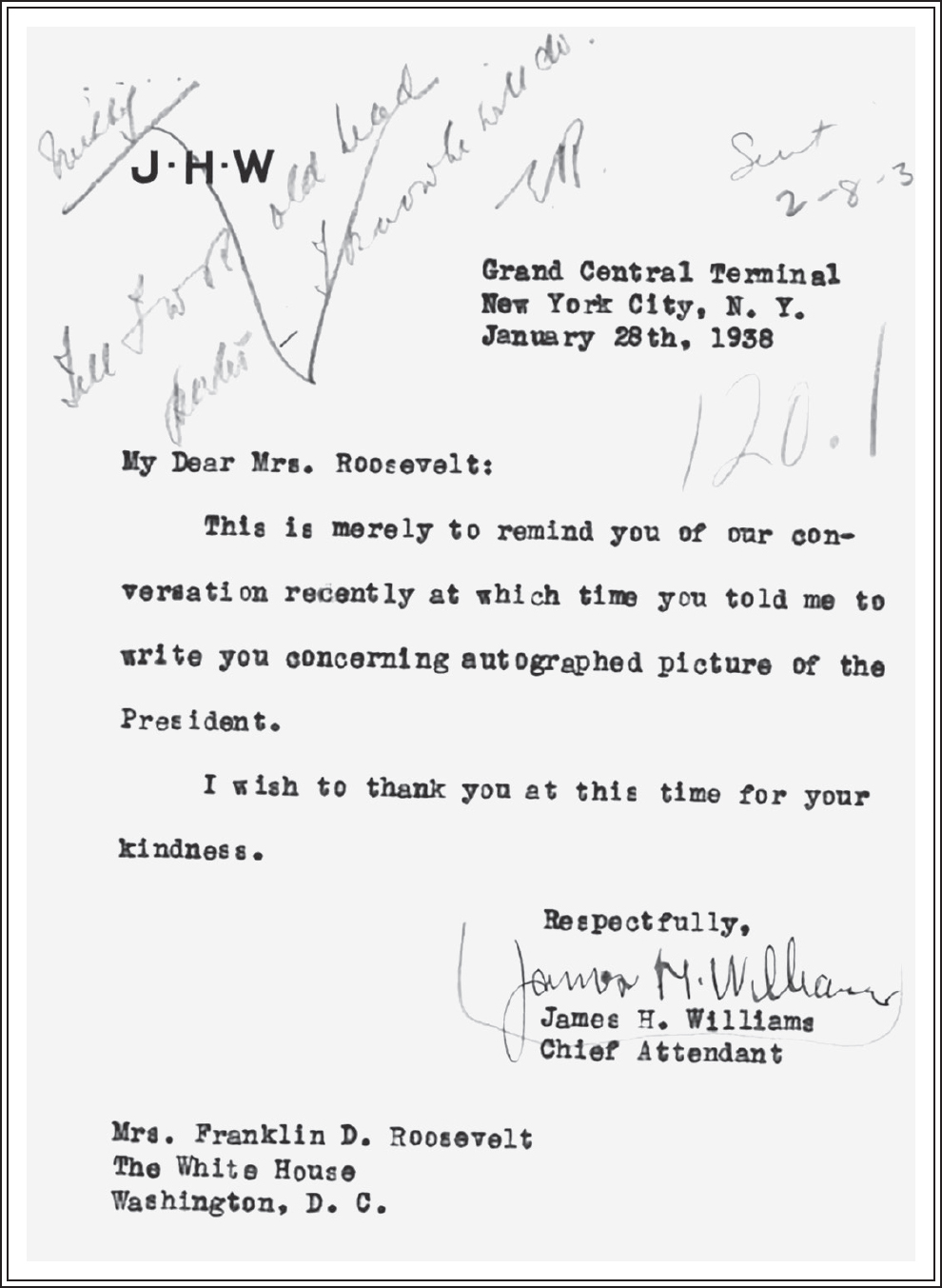

About a week later, on January 28, Chief Williams typed a letter to Eleanor Roosevelt, reminding her of a conversation in which she had promised to send him an autographed photo of President Roosevelt. Williams had known Mrs. Roosevelt for years as a stalwart New Yorker, with an admirable aplomb at dodging her irksome security. Five years earlier, when no one had met the first-lady-to-be returning to Grand Central Terminal from Chicago, Mrs. Roosevelt simply “gave her small overnight bag to a red cap like any other passenger, walked through the station,” and went home in a taxi.11

Now Mrs. Roosevelt’s private secretary “Tommy” (Malvina Thompson Schneider) handled Chief Williams’s letter, to which she hurriedly attached her own note—penciled on an upside-down slip of White House letterhead—to forward to FDR’s private secretary: “Miss [Marguerite] LeHand, This man is head porter at Grand Central Station—always meets Mrs R + knows the President. Mrs R promised him a photo from the President + herself! MTS.” Mrs. Roosevelt intercepted the letter from Tommy; to ensure that the message would be seen to, she penciled across Williams’s letterhead in the upper left corner: “Missy, Tell FDR old head porter,” she instructed LeHand. “I know he will do. ER.”12

Chief Williams’s letter might have been a straightforward request for a presidential souvenir, but it seems just as likely a politic ruse to draw Mrs. Roosevelt’s attention. While he could speak freely about some things, his position required that he broach certain subjects—such as the increasingly volatile labor disputes—with circumspection and tact. Whether their tacit correspondence amounted to anything or nothing, both the Chief and the First Lady would have known that the International Brotherhood of Red Caps, led by Townsend, had just opened its office headquarters in the capital and was mobilizing for a wage war against the railroad companies.13

In 1938, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt intercepted Chief Williams’s letter from her secretary to give it her personal attention. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library.

As the Chief’s union men were preparing for battle, his boxing friend was ceremoniously taking off his mitts. In the spring of 1939, Joe Louis wanted to celebrate his twenty-fifth birthday in Harlem, so Chief Williams booked himself at Club Mimo for May 13. That Saturday a varied cast of adoring friends turned out to fete the boxer, their beloved “Brown Bomber.” Manager Mal Frazier arranged the Mimo’s sumptuous and starry affair: Wilhelmina Adams hosted, and Ralph Cooper of the Apollo, as master of ceremonies, read aloud all the incoming felicitous telegrams. Bill Robinson could not attend, but his wife Fannie Clay spoke on his behalf. Other notables on hand to toast the young champ included actresses Ethel Waters and Fredi Washington; journalist Thelma Berlack Boozer; Roy Wilkins; Harlem Hospital surgeon Louis T. Wright; and bandleader Duke Ellington. Though not recorded, a published roster of the young boxer’s friends whom Cooper called up to make speeches included Lieutenant Battle and Chief Williams.14

In early July 1939, the issue of whether tips legally compensated Red Caps instead of a minimum hourly wage drew station attendants to a two-day hearing in Washington. Workers came to testify from Philadelphia, Boston, Harrisburg, Jacksonville, St. Louis, Cleveland, Kansas City and New York.

A wage-hour bill had been enacted whereby railroads and terminal companies required Red Caps to sign individual contracts guaranteeing them twenty-five cents an hour. But every Red Cap was required to report his tips, which were to be considered wages. The agreement stipulated that a Red Cap receiving two dollars in tips for an eight-hour day would earn no wage for that day’s work, and that if he made less, the railroad company would make up the difference.

By and large, the hearing revealed, Red Caps were afraid to report less: they daily turned in their obligatory receipts from the tipping public, reporting their two-dollar take whether they made it that day or not for fear of reprisals if they dared ask the railroad for money. Conversely, as John Lee, a thirty-year veteran of Grand Central’s Vanderbilt Avenue entrance, testified. “I have a very advantageous location at Grand Central Station,” he said. “I’ve been there so long people know me by name. Their ego wouldn’t allow them to reduce their tips.”15

In Grand Central’s early years, Chief Williams had effectively organized and inspirited his men through numerous mutual benefit and philanthropic enterprises, but many pundits regarded the Red Caps as impervious to unionization. As a labor force that needed no particular skill set, as compared to Pullman porters or waiters, workers with grievances had “virtually no leverage vis-à-vis railroad station management,” as a historian later noted.16 Chief Williams had notably populated Grand Central’s crew of menial laborers with college students, some of Harlem’s most ambitious young men. He took great pride in being able “to help the young man who is trying to help himself,” and he pointed constantly to the many erstwhile Red Caps who had made careers or had expertise in law, medicine, and almost every field imaginable. He claimed that the Red Cap sector supported more college-going men than any other terminal department. “This year we employed 101 college men,” he told Abram Hill in 1939, “25 of them graduates.”17

Why did college graduates stay on afterward? It’s understandable that young men might tolerate such grunt work to defray their college expenses. But what kept some redcapping after graduating—even after establishing businesses? The rude awakening for many was that a diploma did not ensure the ability to break through certain prevailing Jim Crow barriers. Redcapping, however taxing, was at least a viable moonlighting occupation.

One of the station captains acknowledged that the Chief carried out a trying job admirably, which perhaps made their own not only bearable but purposeful. Indeed, whether every Red Cap loved him or not, “he is deeply respected by everyone.”18 Their high esteem for Chief Williams personally did not invalidate the Red Caps’ occupational dissatisfaction—which grew more acute. But even during the most heated arguments on Red Cap labor issues, personal censure of the Chief was indeed rare.

During their efforts to form a labor union, Chief Williams was conspicuously silent. The columnist James Hogans noted: “There is one subject . . . on which Jim will not commit himself: this is, the union movement among redcaps. What his opinion is about the matter he discreetly keeps to himself.” Hogans posited that Williams’s decades-long tenure as Chief was likely due to his “ability to keep his own counsel and not speak out of turn.”19 Perhaps Hogans was damning the Chief with faint praise by noting his silence. On the other hand, Hogans was more cognizant than most of the delicate balance, and leverage, of Williams’s position. Conceivably Hogans considered the Chief’s avowed neutrality as a tactical gambit: railroad executive antagonists of the Red Caps’ union might rest assured that their sole Negro manager was loyal. In the black press, Williams was a visible supporter of labor-strong social organizations, and of labor-friendly political candidates like Herbert H. Lehman, who was then campaigning for governor.

In September 1939, as the unionization effort gained more heat, the Age ran a flintier headline: “‘Chief’ Williams Remains Silent as Grand Central Terminal Holds Labor Representations.” The Red Caps had won legal clarification of their job status. The rail transport lines had tried to block their petition, contending that Red Caps were merely “privileged trespassers” or “concessionaires.” But the Interstate Commerce Commission overruled them, deeming porters to indeed be railroad company employees.

On the day when the National Mediation Board was supervising a labor election for the terminal’s Red Caps to vote on the question of union representation, Williams was again taciturn, but explicitly so. “Do not ask me to say anything,” he said. He’d lowered his signal whistle from his lips only to eschew a reporter’s questions. “I am not allowed to discuss it,” he explained, because of his supervisory position.20 Yet with a courtesy worthy of a stage whisper, played for an audience, the Chief gratuitously clued in the reporter as to which union point persons he should talk to who were monitoring the voting in the terminal: There was John A. Bowers, vice president of the International Brotherhood of Reds Caps (IBRC); and there was John R. Lee, the driving force and president of the New York system’s brotherhood.

The wheels of Grand Central’s labor relations may have seemed to Williams—who was once their principal impetus—to be turning now of their own volition. If his position enjoined him from demonstrably revealing either his solidarity with or his disdain for this change, no one appears to have measured his silence ponderously. As his men cast their votes in favor of representation by the IBRC, his signal whistle resumed its intermittent chirrs that echoed through the great marble concourse.

In January 1940 the second annual International Brotherhood of Red Caps convention was held in New York at the YWCA’s Emma Ransom House (at 137th Street and Seventh Avenue) in Harlem. Being management, Williams did not attend the convention, though shop talk, neighborhood social gatherings, and newspapers readily informed him of its proceedings. Several notable labor leaders and politicians sent greetings to the convention, including officers of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union and the National Women’s Trade Union League of America; New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia and New York governor Herbert Lehman; educator Mary McLeod Bethune; Chicago Defender publisher Robert Sengstacke Abbott; and Abyssinian Baptist Church pastor Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. (who had succeeded his father).

Red Cap John Lee, the union shop steward, had been at Grand Central about as long as Williams, since they were young neighbors on 134th Street. As chairman, he called the three-day convention to order, and IBRC president Willard Townsend presided. During the Great War, Townsend had been briefly married to Williams’s friend Alberta Hunter, whose father had been a Pullman porter. Townsend introduced A. Philip Randolph, of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, who addressed the convention.

The Red Cap workforce fell under the jurisdiction of the Union of Baggage Clerks and Carriers, whose membership was white and which “withheld . . . benefits and opportunities from the Red Caps over whom they claim jurisdiction,” including salary, voting and seniority rights for jobs. The Pullman porters and Red Cap porters—both predominantly black railroad workforces—might have united in a formidable alliance against the Baggage Clerks and Carriers Union. However the Red Cap union, opting for autonomy, voted not to affiliate with the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. It also changed its name from the International Brotherhood of Red Caps to the United Transport Service Employees of America (UTSEA).

One adopted resolution complained that “the Pullman porters publicly criticize the red caps in the presence of passengers as being lazy and no good” and formally requested that Randolph instruct all Pullman porters to cease such behavior.

But more broadly, the Red Cap membership voted to immediately start organizing red caps and porters beyond railway stations, in bus terminals, airports, and docks, and to include cleaners, sweepers, janitors, and elevator operators nationwide.

They voted to support Black American Sugar Cane workers who were currently protesting the importation of offshore refined sugar. In light of the recent outbreak of a second European war, the convention pledged to cooperate with the Keep America Out of War Congress and the Labor Anti-War Council.

The shortest resolution required no preamble: the convention endorsed the New York Democratic representative Joseph Gavagan’s Anti-Lynching Bill, which was then before Congress. The House of Representatives had passed the bill in 1937, but a number of Southern lawmakers were determined to hold on to white supremacy in the Senate. “Some of the southerners, of course, are not charming,” the Crisis had written two years before, “but many of them are reasonable men—except on the Negro. By that reasoning peculiar to some sections of the South, they argued that passage of an anti-lynching bill would be a signal for the wholesale raping of their wives, daughters and mothers by ‘black brutes.’”21

After heated discussion, the members voted to grant honorary life memberships to three men for their financial and moral support: Julian D. Steele, a black settlement house director and a rising star in Boston area social work; Alfred Baker Lewis, a white union organizer and NAACP member; and Henry Longfellow Wadsworth Dana, a white labor activist and Harvard professor.

Chairman John Lee bade the convention to stand in a moment of silence for American Newspaper Guild founder Heywood Broun, a staunch friend of the union, who had died a month earlier. Broun had sat on the advisory board since the IBRC’s first convention in Chicago the previous year, and his columns were occasionally reprinted in the Red Cap industry monthly, Bags and Baggage. Broun had been the first columnist to champion the organizing efforts of the Pullman porters back in 1925; James Hogans asserted that “his writings had much to do with molding public sentiment in their behalf.”22

Williams knew personally many of the public figures who were present. And a few of them, like Reverend Powell Jr. and Lester

B. Granger, he had hired nearly twenty years earlier as Red Caps. Notably Granger, who Williams once caught wooing his daughter Gertrude on work time, was now assistant executive secretary of the National Urban League, whose mission was to desegregate racist trade unions.

By and large, the convention was a triumph. By month’s end the New York Central Railroad, the Grand Central Terminal Company, the Michigan Central Railroad, the Cleveland Union Terminal, and the Red Caps’ UTSEA signed an agreement covering some seven hundred station Red Caps and corollary workers.23

But formidable opposition to UTSEA’s efforts predictably came from George M. Harrison, president of the Brotherhood of Railway Clerks, which constitutionally banned all but white men. Negro railway clerks could join only “auxiliary locals,” which required them to pay membership dues but barred them from policy-making conventions. “Harrison was like the dog and the bone,” Hogans later wrote. “He didn’t want the Negro Red Caps himself, but he didn’t want anyone else to organize them.”24 Harrison’s efforts to derail and coopt the new Red Cap union helped Townsend and others to engage the invaluable media and legal resources of the Urban League and the NAACP. A few months after the Red Cap convention, Townsend met at the 135th Street Y with representatives of several New York Central locals to consider proposed revisions to the UTSEA contract, soon to be presented to the railroad company management.25

In June, Grand Central converted the women’s room on the lower concourse into a Red Cap check room, an overdue improvement for workers.

Being a major transit hub, Grand Central had ample distractions from labor tensions. On March 16, 1940, at about one o’clock in the afternoon, Chief Williams was passing through the terminal in his civilian clothes, a plump green carnation in his lapel marking the eve of St. Patrick’s. An odd sound halted the Chief as he neared the baggage room. “I heard a zip like a skyrocket,” he told police detectives afterward, and an audibly crackling blaze prompted him to blow his whistle. The baggage room counterman, a nearby clerk and Red Cap, and he himself emptied “eight or ten” extinguishers to put the flames out. A low level time bomb was found attached to two wristwatches set for nine o’clock. Police suspected the detonation was intended for another time, possibly another location, an isolated incident. Yet a bit of press was perhaps wryly telling: “The chief attendant is the father of Battalion Chief Wesley Williams, only Negro of that rank in the [fire] department,” the Times wrote,26 unwittingly revealing the increasing eclipse of Chief Williams’s fame by his son.

On June 1, 1940, New York’s Grand Central, 125th Street, and Pennsylvania stations joined several other northeastern stations in putting into place a uniform, universal tipping system that was to become effective countrywide. In adherence with new National Labor Relations Board’s minimum wage requirements, the railroad company would pay Red Cap porters thirty cents an hour—or $2.40 a day—in addition to a fixed tip amount of ten cents per bag. The policy was advertised “to improve and standardize Red Cap porter service to the public.”27 Indeed, many Red Caps initially regarded the establishment of the system as a victory, as it would now guarantee them a calculable salary.

But the new rate met with strong objection from Red Caps in New York. While the measure ensured the traveling public uniformity, it threatened to diminish a Red Caps’ opportunities to potentially earn more, or the ability to make a decent living. Under the old system, a passenger might hand a Red Cap his five bags with a twenty-five-or thirty-cent tip. “Two of the bags might be large, the other three small,” John Lee, a Grand Central Red Cap and UTSEA officer, explained. “Now the passenger carries the three small bags himself and gives the red cap 20 cents.”28 Red Caps soured over the restrictive policy during the next year.

“There’s no more sugar on Sugar Hill,” Samuel H. Boyd, a Red Cap captain, testified at City Hall. On August 7, 1941, the U.S. Labor Department was hearing New York workers’ testimonies about the new system. The gray-haired Boyd had long supervised the terminal’s Vanderbilt Avenue entrance, nicknamed for Harlem’s distinctly affluent enclave. He had been at Grand Central since 1905, almost as long as the Chief, and the two men were brothers in Elkdom as well as Harlem and Williamsbridge neighbors. Boyd now asserted to the department’s Wages and Hours division representative, Thomas Holland, that the Vanderbilt Avenue Red Caps felt that they were making less under the new ten-cent-per-bag policy than before: “There used to be a lot of sugar there, but there’s none anymore,” he said frankly. “So you were pretty happy under the old tipping system?” Holland pressed for clarification. “I would not say I was happy,” Boyd responded. “But I did do better under the [old] tipping system.”29

The Red Caps’ issues were complex. They wrestled for months to clarify the essential question of whether they worked for the railroads that hired them or for the public they depended on—to no wholly satisfying resolution. Even First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt questioned whether Red Caps’ tips ought to be considered as wages. At a National Urban League gathering in New York, she had addressed the conundrum: should the expense for carrying handbags rightly be borne by their owners, or by the porters, or by those who run the railroads? She posited that the question was one of national import, revealing “what we in our country want for the people who perform services which are worthy of pay.”

Do we want in our country to have something we know of as tips considered a living wage? I don’t think we do . . . but in any case I think it is an obligation . . . for every citizen in a democracy to think about such questions.30

For Chief Williams and the Red Caps, these and all manner of other questions about their democratic standing would soon be abundantly forthcoming.