CHAPTER 13

“Things Reiterated as the American Way”

Soon I shall be a soldier fighting for those things that are constantly being reiterated as the American way.

—LEN BATES, 1943

On June 26, 1941, the New York parks department held its sixth annual barbershop quartet contest. About fifteen thousand people gathered at the Naumburg Bandshell on the Central Park Mall to listen to eighteen a cappella singing groups perform. The contest judges included the parks commissioner Robert Moses, former New York governor Alfred E. Smith, and Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, who in the promotional brochure had personally invited “all harmonizers” to participate. The winning group would go on to St. Louis to compete at the finals, held by the Society for the Preservation and Encouragement of Barber Shop Quartet Singing in America, or SPEBSQSA.

At least since the 1870s, African Americans had fostered a popular close-harmony singing style for four unaccompanied voices. In 1879 the white Massachusetts abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison’s funeral featured “a colored quartet, and the musical selections . . . designated by [the deceased] before his death.” Similarly, in Washington, D.C., James Garfield and Chester A. Arthur’s 1880 presidential ticket got a boost from black journalist John Edward Bruce’s four-man Black Republican Glee Club. Though steeped in black spirituals, the quartet style also lent itself well to popular ballads. As white singers adopted the quartet’s economy of voices—and adapted its repertoire and image—the performance style quickly flourished in social, music hall, and recording settings as “barbershop quartet,” a rubric of musical Americana that excited widespread competition.

For the Grand Central Red Cap Quartet the singing challenge in Central Park must have been irresistible. Perhaps ex-governor Smith, an enthusiast and contest official, had encouraged his friend the Chief to get the quartet to compete. In any case, they entered the contest and sang two numbers from the approved list of barbershop ballads. One of the singers was sick, so a fourteen-year-old relation stuck on a fake handlebar mustache and stood in for him at the last minute—and still they won.

Despite the group’s name, the Grand Central Red Cap Quartet that won the New York City competition was not the same as the one Robert Cloud formed under Chief Williams around 1930. This new incarnation consisted of Owen Ward, second tenor; his brother Robert Ward, baritone; their nephew Jack Ward (a tenor substitute); and William Bostic, bass. The group originated as a family act called the Four Southern Singers or sometimes the Southern Singers Jug Band, which included James Hornsby “Jim” Ward, bass, and his wife Annie Laurie Ward, singing tenor. By 1933 the quartet had recorded “Be Ready” and “Old Man Harlem” and appeared to be doing well enough that Owen Ward’s manager gave him a new alligator-skin violin case.1 When the group broke up, Chief Williams gave the men work. The former Southern Singers soon regrouped and could be heard singing together during spare hours at the terminal.

Being familiar voices from radio, and likely aided by the Chief’s introductions, they gained entrée to entertain railroad officials and to appear as featured guests on broadcasts like Major Bowes’ Amateur Hour. Of course, now performing as the Grand Central Red Cap Quartet, the contest win in Central Park was a big deal for the singers and the Red Caps corps collectively.

But even city officials had been excited by the prospect of winning since the previous year. On July 15, 1940, New York had lavishly hosted SPEBSQSA’s second national convention and competition at the 1939 World’s Fair, which was in its second year. Spearheaded by Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, and former governor Alfred E. Smith—all of whom were judges, then and in 1941—New York had outbid several other major cities vying to host the 1,800-member society’s event.

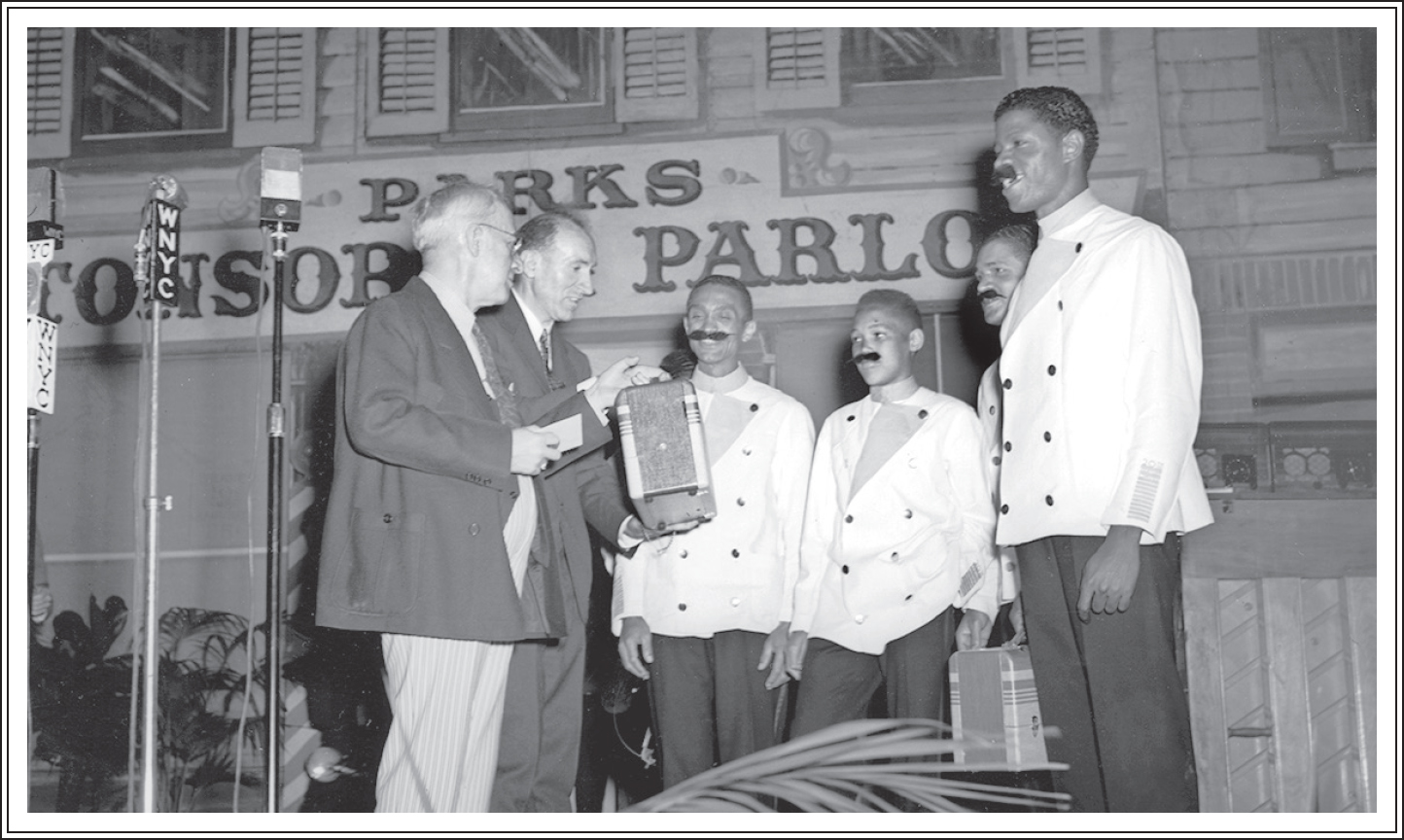

In the summer of 1941, the Barbershop Harmony Society barred the Grand Central Red Cap Quartet from its national competition in St. Louis, Missouri, due to race, prompting resignations from two New York officers, parks commissioner Robert Moses, and former governor Alfred E. Smith. New York City Parks Photo Archive.

SPEBSQSA’s convention happened to coincide with the fair’s “Negro Week,” which Mayor La Guardia kicked off by opening a literary exhibit from the Schomburg Collection in the American Common:

Show me in the records of history any race anywhere that in our generations have contributed to science, the arts, government itself and have above all attained a position of dignity to fight for their own people than what has been accomplished by Negroes of America, and you will defy history itself.2

An ongoing production at the fair called “Railroads on Parade”—a pageant set to music by Kurt Weill—included a dozen black WPA actors portraying Red Caps, Pullman porters, and other essential workers in American railroad history. Across the fairgrounds, on the plaza in front of the New York City Building, ex-governor and contest judge Smith, wearing a brown derby, led the audience and other judges in a round of “East Side, West Side.” The quartets’ participation in the 1940 fair had clearly won over New York City’s officials, who were gung-ho about the present victory of the Grand Central Red Cap Quartet.

On June 27, the day after the 1941 quartet competition, Parks Commissioner Moses notified SPEBSQSA that New York would be sending the winning Grand Central Red Cap Quartet to compete in the finals in St. Louis. But O. C. Cash of SPEBSQSA, who received the telegram, was not in harmony with New York’s results: the society had a whites-only policy. The previous year, at the World’s Fair, SPEBSQSA had recognized the Southerners, a black male NBC Radio quartet, as “honorary members.”3 But no black quartet had ever won a regional competition before, qualifying it to show up in person to the nationals. And as if the Red Cap Quartet’s victory didn’t beat all, New York’s second-place winner was also a Negro team: the Harlem YMCA Quartet.

Cash wrote back to New York, explaining that SPEBSQSA had often discussed whether to allow colored singers to compete “with others,” and that “last year the board came to the conclusion that to keep down any embarrassment we ought not to permit colored people to participate.” He did not wish to offend the organization’s expansive membership base in the South, “where the race question is rather a touchy subject.” Assuring the New Yorkers that he and the Society’s president were not “narrow about such matters,” they nevertheless did not want to broach “a question of this kind.” With that awkwardness aside, he added, “I hope you will be in St. Louis with the other quartets.”4

Upon receipt of this letter, Parks Commissioner Moses and ex-governor Smith, both of whom were vice-presidents of SPEBSQSA, quit. Moses railed at Cash’s and the organization’s absurd bias in a letter that he shared with the press:

The first and second quartets were composed of colored men. The judges took their duties seriously and even insisted that the four leading quartets sing a second time before the final decision was reached.

We are now informed by your recent letter and telegram that colored quartets may not compete in the National Finals in St. Louis. If we had known this before we should immediately have dropped out of the national organization, a step which we are now compelled to take.

It is difficult for me to see any difference between your national ballad contest and a national track meet in which colored men run in relays or compete individually. This is not a social event, but a competition, which should be open to everybody.

Let me add that if American ballads of Negro origin are to be ruled out of barber shop singing, most of the best songs we have will be blacklisted. There was a man named Stephen Foster who never hesitated to acknowledge his debt to the Negroes for the best of his songs. Along with many others [who] found pleasure in the harmless amusement of American ballad contests, I am very sorry that this sour note has marred our pleasant harmonies.

Ironically, Moses’ demonstrable racial solidarity here appeared at odds with his own vexing flights of prejudice—but it was affecting. Smith also lambasted the board of directors in St. Louis for ruling out the winning singers “because they are colored men,” as he, too, resigned from the society: “I assume that the New York State organization will go on independently of the international organization.”5

Back at Grand Central, the mood in the Red Cap Check Room was a mix of resignation and triumph. “You know how a man feels about a thing like that,” said Robert Ward, the quartet’s manager. “It’s their policy—that’s all there is to it.”6 The men had worked hard to win first place, and were of course disappointed to miss boarding a train in Grand Central as regular passengers.

But they were not overly discouraged. They surely did not miss having to find hospitality when traveling in inhospitable places. Chief Williams had already approved their time off, and their fellow porters lavished them with gifts for their prospective trip. The quartet was soon fulfilling requests for public appearances all over the city, occasionally at the behest and in the company of Commissioner Moses.7

By 1943, numerous railroad stations across the country had their respective “Red Cap” musical aggregations. But one particular singing group emerged with the moniker that had no connection to the railroad. In the midst of the 1942–44 American Federation of Musicians’ strike, a rhythm and blues quartet called the Four Toppers, like scores of other artists, sought an unobtrusive way to get around the union’s recording ban. Dubbing itself the Five Red Caps (with an extra member), the group likely maintained its marketing appeal to black audiences by evoking the iconic railway station baggage handlers. The quintet even recorded a peppy ditty titled “Grand Central Station,” which enjoyed much commercial success.

A few weeks after the barbershop quartet fiasco, but unrelated to the competition, ex-governor Smith heard from Wesley Williams on another matter. After more than twenty years in lower Manhattan, Wesley wanted to transfer to an assignment closer to home, specifically on White Plains Avenue in the Bronx. On August 18, 1941, he wrote with hopes that Smith might intercede on his behalf: “May I be allowed to take advantage of your long years of friendship with my father by requesting a favor of you?” Smith’s response is not known, but the younger Chief Williams got his transfer.8

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese bombed the American naval base at Pearl Harbor, an attack that triggered a congressional declaration of war. Though black citizens had thrown themselves valiantly into every conflict of American history, their efforts had been constantly rejected or subject to some arbitrary policy. The very morning the Japanese bombs rained down on American warships, Jim Crow proved to be alive and well. Dorie Miller, a black messman, rushed up from the ship’s galley and flew into action. He had no training in navy guns, and military regulations put them off limits to him. Nevertheless he seized an unmanned machine gun and emptied its fire on the enemy. Afterward Miller climbed back down to the mess galley, “where, because he is a black American, he must remain—in spite of heroism, ability, or the need of the Navy for first-class fighting men.”9

Earl Brown, the Chief’s former Red Cap who was now a prominent journalist, reported this story, which made headlines in the black press nationwide. Writing in Harper’s, Brown articulated the widespread black disaffection with the war. “Because he must fight discrimination to fight for his country and to earn a living,” Brown wrote, “the Negro to-day is angry, resentful and utterly apathetic about the war.” Mrs. Roosevelt had expressed a similar sentiment in a recent speech: “The nation cannot expect colored people to feel that the United States is worth defending if the Negro continues to be treated as he is now.”10

A few days later, and thousands of miles away in New York, workers at Grand Central Terminal mounted an enormous fifty-ton photo mural on the east balcony to promote the sale of defense bonds and stamps. The mural—stretching 110 feet high by 118 feet wide—was said to be the world’s largest. Certainly no one entering the station could fail to notice the montage of images of servicemen, children and laborers—all of whom were white. Williams and the Red Caps surely saw it as a reminder that complexions still outranked qualifications.

The onset of another world war must have struck Williams as eerily familiar. Countless Red Caps had served as officers and soldiers in the 369th “Hellfighter” and 367th “Buffalo” regiments. And when those who survived had returned after the war, he had given work to dozens of veterans. They were retired now, visibly gray and wizened in their whipcord coats and red caps. One might bet they could tell you about the Great War “over there.” And why they might be skeptical about this one. But when as always Negroes went to the country’s defense after Pearl Harbor, the Chief sometimes patched vacancies in the staff by calling back these “outside men.”

One of the young fellows over there now had been a Red Cap back in the ‘20s, and who the Chief and some of the older men perhaps recalled, was Joseph L. Washington. They knew Joe’s father better: back in 1895 Thomas Washington had started as a Pullman porter down south before he moved north in 1907 to work for the New York Central. The public often commonly pegged Williams and Washington as “porters to Presidents,” the Chief inside the terminal and his Pullman counterpart aboard the Empire State Express. Though Pullman rules forced Washington to retire at seventy in 1929—he rode between Grand Central Station and Buffalo for more than twenty years—his income had afforded academic opportunities to his ten children, especially his son Joseph. In 1920 young Joe, a student at Erasmus Hall High School, became captain of the football team; won the school’s “highest honor possible” in athletics, its prestigious John R. McGlue Trophy for the best all-around record; was athletics editor of Erasmus’s yearbook, the Flying Dutchman; and almost won the student government presidency. Washington’s athletic excellence gained him a scholarship to New York University—and to Chief Williams’s university of Grand Central.

During Joe Washington’s three years at NYU, he became secretary of the student body and distinguished himself on the school’s baseball and football teams. He then went to Colby College in Maine, where he graduated with a bachelor of science in the class of 1927, eager to enter medical school. Several leading U.S. colleges reportedly accepted him, then rejected him due to clerical errors when he showed up Negro, so he applied internationally. Hearing nothing for months about a particular application, “he hopped a steamer, worked his way across the Atlantic and reported to the University of Edinburgh,” where the Scottish school apparently had no issues with accepting him.

Back home, the Chief and all the Red Caps and Pullmans keenly awaited news from Tom Washington’s boy, who had become one of their own. On December 10, 1927, the Age reprinted part of a letter from Joe to his father: “Father, it’s all like a dream to me to be here and find the place and people so congenial. It’s the best treat you’ve given me in my life. I hope never to forget it, and will do my utmost to make good in appreciation of it. I pray to God that I’ll be a success.”11

But Joe’s road to success soon came to an impasse. Despite his high marks, his finances were dwindling, and students at Edinburgh were not allowed to work. Worse, an official suggested he quit. “Universities should be attended only by those who have the means,” he told Washington. “You do not have the means.”

Joe Washington ignored the advice, eked through, and earned his medical degree from Edinburgh. But a medical school graduate required a license to practice legally, and obstacles thwarted his every effort. In 1938, as tensions threatened to draw Britain into the war, Washington was unable to attend his father’s funeral back in the States. After the war began in 1939, dogfights ignited the English skies, and for months Washington treated the wounded in a small hospital in Lancashire. He subsequently toured in Africa and other countries, earned the rank of captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps, and married a local girl in Scotland. There he made his home as a contract physician, still struggling to get a license.12

Even as an officer, gaining a bona-fide license might not have solved Joe’s problems back in his home country. Maj. Ralph B. Teabeau, a star player on Howard University’s baseball team and a member of the Grand Central “nine,” was an enlisted officer in both world wars. He ranked Lieutenant in the first, and Major in the second. In 1942 he headed the U.S. Army’s dental unit of the “all-Negro setup” at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, but was demoted so the military could install white officers in the infirmary instead.13

In 1941, up in Harlem, A. Philip Randolph was organizing a March on Washington movement. The apt slogan on its flyers read: “Winning Democracy for the Negro Is Winning the War for Democracy.” Chief Williams could attest to the U.S. Army’s caprices at Grand Central, as one of his student Red Caps, Leonard Bates, tried to move up in the ranks to a gateman’s position. In the fall of 1940, Bates had gained national headlines as a preeminent NYU football star. When the NYU team was scheduled to play the University of Missouri team, the Missouri officials objected to any Negro playing on their field, a reference to Bates, the NYU team’s only black player and its star fullback. NYU officials capitulated, agreeing in writing to uphold the color line by signing a “mutual pact.” Students were outraged. Dozens of student groups rallied in solidarity with the wronged athlete—fraternities, the American Students Union, drama clubs and others—to protest NYU’s decision. “Bates must play or the game be canceled,” the student chairman Guy A. Stoute wrote to Walter White at the NAACP. “Students have already signed over 2,000 statements in protest against this discrimination.” NYU turned a deaf ear to them and upheld its agreement to bench Bates. He did not board the train bound for Columbia, Missouri, with his white teammates.14

Bates focused instead on maintaining a good academic average, redcapping as he earned his sociology degree. When war came, Bates and his wife were newlyweds and had a child on the way. He wisely decided to try to move up in the ranks at Grand Central and become a gateman, controlling platform access to ticket-holding passengers—a job with a higher pay grade. Having helped enough “green” gatemen decipher train schedules, he knew the terminal was in short supply of men and had become lax in training them.

But the New York Central turned him down. A terminal manager admitted the company had never hired a colored gateman; perhaps none before Bates had had the temerity to apply. L. W. Horning, New York Central’s labor relations president, denied color had anything to do with it. Rather, every contract had a “scope rule” describing the positions in the department covered in the agreement. “You just can’t move men from one class to another without fouling these scope rules,” he claimed. If redcapping didn’t satisfy Bates anymore, Horning asked, would he prefer to apply for a mail-and-baggage porter’s job?

In the spring of 1943, Bates earned his degree in sociology. He doffed his red cap to don the army’s khaki, but not before first mailing a letter of protest to New York Central, and sending a copy to the federal Fair Employment Practices Committee. A few newspapers printed some of the former athletic star’s righteous complaint:

Just a short time ago I applied at your office [of the stationmaster] for a job as gateman. First I was told that the Brotherhood [of Railroad Clerks] did not employ colored persons. When I pointed out that the Brotherhood had nothing to do with the hiring of gatemen, I was told that the job “was all filled.”

When I disputed this, I was finally told that the NYCRR did not employ colored persons in this capacity. Your company should be proud of this record [wherein] it proclaims even in posters and signs that it is all-out for the war; that all kinds of records are being broken.

There is just one area in which it remains constant: it still does not think that the colored person fits into the general scheme of things. His is a different world. He must remain menial. Be polite and know his place. This has got to change.

You have tyrannized, intimidated, and plagued the colored worker. . . .

Soon I shall be a soldier fighting for those things that are constantly being reiterated as the American way. I want to be a good and efficient soldier. I want to draw my inspiration for killing the fascists I face on the front from those I have known at home.

Bates signed the letter “your fellow American,” adding as a postscript: “I shall save this for my boy when he becomes of age. This will be his first lesson in American History.”15

Williams’s own son, Wesley, was fighting the war at home. In the mid-1940s, nearly a quarter-century after he entered the force in 1919, he was still the only black officer in the whole New York City fire department. While the war raged abroad, he and other black firemen were waging a war against discriminatory practices at home. The black firemen’s grievances included a medical plan that used a code indicating they were “to be first referred to Negro physicians”; their being bypassed for assignments to fireboats, rescue companies, the band and company baseball teams; their difficulty in obtaining transfers to companies where no other blacks were assigned; and the fire department’s tabulation of Negroes as “the only personnel list kept on a racial basis,” whereas it kept no similar list for other ethnicities. One officer of the Vulcan Society, the fraternity of black firemen that Wesley recently co-founded, cited the absurdity of this sort of list, “for there are Negroes whose names do not appear because they are not obviously Negroes and in one instance a man who insists he is not a Negro is listed.”

Another grievance was that the fire department routinely reduced the seniority of black firemen in order to promote their white counterparts as officers. This was particularly galling since departmental orders explicitly mandated preferences for particularly qualified members for certain assignments. “In one company,” Wesley’s group pointed out, “the only college graduate is a Negro. Yet when the Department order was received, specifically stating that men with the best educational background should be given preference, in making the assignments as Red Cross Instructors and Auxiliary Speakers, we find that the Negro man was passed over constantly.”16

Perhaps the most egregious offenses were the segregated sleeping arrangements, often painstakingly arranged. Wesley followed his father’s example by writing to Judge Hubert T. Delany and others to ask for their help in ending Jim Crow beds in New York station houses. At his behest, Walter White wrote Mayor La Guardia. Wesley also helped orchestrate City Council hearings on the matter. He admitted wryly at one meeting that conditions had improved to some degree since he started twenty-five years before, when he was assigned to sleep in the cellar. “The Captain said he thought I would be more comfortable there,” Wesley, now a battalion chief, said. “But we didn’t agree on that point so I was given a bed by the toilet.”17

Back at Grand Central, despite their myriad reasons for disillusionment, Chief Williams’s Red Caps nevertheless answered their country’s call to help the war effort. A number of them responded to the nation’s heightened anxiety and alertness by establishing an emergency medical corps in the terminal.

A registered nurse observed how inconspicuous, well-equipped hospitals attended to the traveling public in New York’s railroad stations:

At the Grand Central, five doctors serve the hospital, one of them always on call nearby at night. Registered nurses of wide experience . . . are on duty every day, two at the Grand Central, and one at the Pennsylvania, with extra nurses for emergencies and holidays. . . . A knowledge of community resources both within the station and outside is important.18

Chief Williams knew his Red Caps were just such a community resource: when one of the men wanted to organize a Red Cap first aid unit, he green-lighted it. Jonah R. Davis was on the scene when a traveler had had an accident, and he was able to apply his own training to help. Convinced of Davis’s knowledge, Williams vouched for the terminal to commission the young man to organize a first-aid class: Davis oversaw a number of station volunteers including other Red Caps, policemen, gatemen, and the stationmaster’s force. The encouragement and hands-on opportunity no doubt gave Davis an incentive to continue his medical studies that led to his career in dentistry.19

“Grand Central Terminal is a parish. A big one and a mighty good one,” said Ralston Crosbie Young, officially Red Cap no. 42 but better known as the Red Cap Preacher. During the war, every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday at noon, he stole away from Grand Central’s congested concourse and passed through the archway of Track 13. A little farther within, in the hush of an idle railroad coach, the Red Cap Preacher conducted prayer services for a microcosm of the station’s disparate sea of humanity. Though some of his co-workers ribbed him, Young’s unassuming evangelism gave solace to anxious commuters, soldiers, businessmen, merchant seamen, and lonely hearts. It also garnered him invitations to speak at far-flung churches and colleges, and flurries of press for many years. “I wouldn’t trade my job here for any in the world,” he said. Then, having done with his ethereal errand, he resumed his earthly duties of trucking luggage.20

Chief Williams unavoidably witnessed the ominous specter of war as it penetrated the terminal in even mundane ways. Upon the shallow landing high up on the south wall, workmen darted about at the curved base of the magnificent zodiac ceiling. Their almost inconspicuous silhouettes carried out some daily task as casually as when they had hung the great photo mural. Way up there, they moved along the line of five half-moon sidelights: from these windows, the bright midday beams shot through daily like searchlights, lazily sweeping the marble concourse floor. One can’t say what nostalgia, or disquiet, stirred the Chief to look up at the workmen: assigned to dull the terminal’s visibility in case of an air raid, they systematically blinded every window, one by one, with black paint. But the iconic clock kept time all the while.