CHAPTER 14

A Second Marriage

No, sir, that’s not the quickest way to the restaurant. I know all the short cuts.

Ought to. I’ve been here thirty-seven years.

—HILDEGARDE HOYT SWIFT, 1947

Williams’s relations with the management of the Dunbar Apartments remained civil under pressure, despite occasional annoyances. In 1934, his apartment had been damaged when the building underwent renovations. At the time Frank Staley, an agent from Rockefeller’s office, wrote to the complex’s manager, “I went through Chief Williams’s apartment this morning and was very much upset about the way in which we have had to tear it up in order to make our improvements in the ‘M’ apartments. . . . I feel that it is no more than fair that we should not charge the Chief any rent for the month of November.”1 Williams had undertaken costly repairs and improvements on his own—combining his own apartment 3M with 3L, tiling both baths, and installing parquet floors and French doors throughout—appreciably increasing its value.

In 1937 Rockefeller sold the Dunbar complex; it had been Williams’s understanding that the “unpaid balance of $78.66” reflected in his account would be nullified at the time of the sale.2 To the Chief’s exasperation, the charge had not been canceled.

On the morning of January 5, 1942, he ran into Frank Staley passing through Grand Central Terminal. The Chief broached the issue with him, and Staley was sympathetic. Williams followed up in a letter to Staley that afternoon: “It is not my reputation to have indebtedness, and the constant letters from the office relative to this matter are of further annoyance.”3

Staley duly forwarded Williams’s typed letter with his own scribbled approval on it to Philip F. Keebler, Rockefeller’s accountant: “Phil—I would be in favor of this—he was put to a terrible inconvenience for a period of 7 months. . . . Please let me know.” The next day Keebler told Elias C. Stuckless, the Dunbar’s subsequent realtor, that “Mr. Staley and I have decided to cancel the balance due by Mr. Williams, and I suggest that you advise Mr. Coleman [the Dunbar’s manager] of our decision.”4

The Chief’s encounter with Staley in Grand Central was not only fortunate but timely: at the end of that year, yet a new landlord entered the picture, as the $3,000,000 Dunbar Apartments were deeded to the Missionary Society of the Methodist Church.5

Williams’s uncharacteristic testiness might have been due to a change in his domestic life. The Chief had “been vacationing week ends at Oak Bluffs, Mass.,” James Hogans mentioned toward summer’s end.6 For Williams, the exclusive colony on Martha’s Vineyard—“Negro Newport,” some dubbed it—was more than a seaside getaway. Apparently, the Chief was courting.

“I am a widower, and you can say I will not marry again,” Williams had told an interviewer a few years before, adding facetiously, “unless I get some nice lady with a lot of money.”7 His sense of resignation was understandable: Lucy, his wife of thirty-five years, was still only six years gone. But in 1942 he was romantically involved once again. Martha Armstrong Robbins was a few years widowed like himself. Like Lucy, she was a New England gal, originally from Roxbury, Massachusetts. In 1908 Martha, a manicurist, had married Charles Henry Robbins, the official stenographer at Suffolk Superior Court in Boston, assigned to cases in the Massachusetts counties of Barnstable, Dukes, Nantucket, and notably in Plymouth, where he recorded the testimony during the controversial Sacco-Vanzetti trial in 1921.

In the 1920s Martha served as treasurer of the League of Women for Community Service in Boston, foreshadowing her later career. Charles died in 1937, whereupon she quit Massachusetts to become the secretary for the Phyllis Wheatley Home in Ohio. The facility at 4450 Cedar Avenue in Cleveland had been founded in 1927 as a refuge for single Negro women from teens to late middle age; Martha resided as well as worked there. But despite her relocation to Cleveland, she maintained her New England roots, returning summers to her old house at Oak Bluffs on the Vineyard.8

It’s unclear how Williams and Martha met. In 1929 their mutual friends included Lottie Williams, Bert Williams’s widow, whose funeral Martha and her first husband had attended from Boston. In any case, on February 19, 1943, James and Martha married. Officiating at the ceremony at the Abyssinian Baptist Church was Reverend Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., one of Martha’s old friends from the Vineyard as well as a former Red Cap.9

On May 25, 1944, an important social event took place a block from Grand Central in the grand ballroom of the Hotel Roosevelt on Madison Avenue and 43rd Street. The Scottish-American educator William Allan Neilson, president emeritus of Smith College, had founded a “Committee of 100” as a corollary of the NAACP, appealing to Americans to secure equality for “our Negro fellow citizens.” The diverse membership included Helen Keller, Alain Locke, Reinhold Niebuhr, and A. Philip Randolph. To raise $100,000 for the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund, headed by Thurgood Marshall, the committee organized a testimonial dinner. It would coincide with Walter White’s return from fifteen weeks overseas visiting black American troops stationed in Europe and North Africa, as well as White’s twenty-fifth anniversary with the NAACP. The banquet’s keynote speakers included First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, lawyer Wendell Willkie (who made the largest personal contribution of $5,000), and Carl Van Vechten. Duke Ellington’s Orchestra provided the music; the “Father of the Blues” W. C. Handy and William Grant Still gave testimonials—the entertainment alone making it an affair not to be missed.

But the Chief missed it. Martha Robbins Williams sat at table three, a big banquet round, fairly front and center to the dais, with IRS collector James Johnson and his wife and a few others. However, she was without her husband that evening.

Considering his wife’s attendance, what could account for Chief Williams’s absence? An admittedly conjectured clue may be found in a later profile, whose interviewer wrote: “Jimmy bowed again; then for the first time smiled. It was a broad, quiet smile. But it was sudden and, in a way, disconcerting. Jimmy, apparently, had been having a bout with the dentist lately—for the smile was toothless.”10 If Williams was self-conscious, he was unlikely to risk making a toothless greeting to Mrs. Roosevelt and the countless others he knew among the thousand guests. And though alone, Martha may well have brought her own connections to the table.

There was also a considerable chance Chief Williams, while no doubt also invited to attend the Walter White Testimonial, had other personal misgivings. Businessman Harry H. Pace, Williams’s Elk brother and former Strivers’ Row neighbor, had once been active with the NAACP’S New York branch, but he now felt undeservedly slighted by it. The organization was not infallible—Thurgood Marshall once remarked that “there was a redcap at Grand Central Station who brought more than three hundred members into the organization. Somebody proposed that he be put on the executive board. The other board members were horrified. A redcap! . . . ‘What college did this person attend? Who are his family?’”11

Marshall’s aside was unspecific (and numerous Red Caps had worked assiduously for NAACP initiatives). But the remark was telling, especially if that unsuccessful nomination to the executive board was Chief Williams’s.

The yuletide week of 1947 was seasonably white but not festive. On December 26 a twelve-hour storm blanketed the city under more than two feet of snow and caused over two dozen deaths. Days into the new year, the record-breaking snowfall—which, except for mortalities, had surpassed the three-day Blizzard of 1888 of Williams’s childhood—was still keeping emergency crews deployed. Grand Central was normally deserted after midnight but was now a nexus of irritated travelers, the snowbound delays having made the main concourse “a Stalingrad of desolate refugees,” as journalist Alistair Cooke described it. Sixty-nine-year-old Chief Williams hustled to coordinate the Red Caps, conceding the congestion was the worst he’d seen in more than forty years at the station.

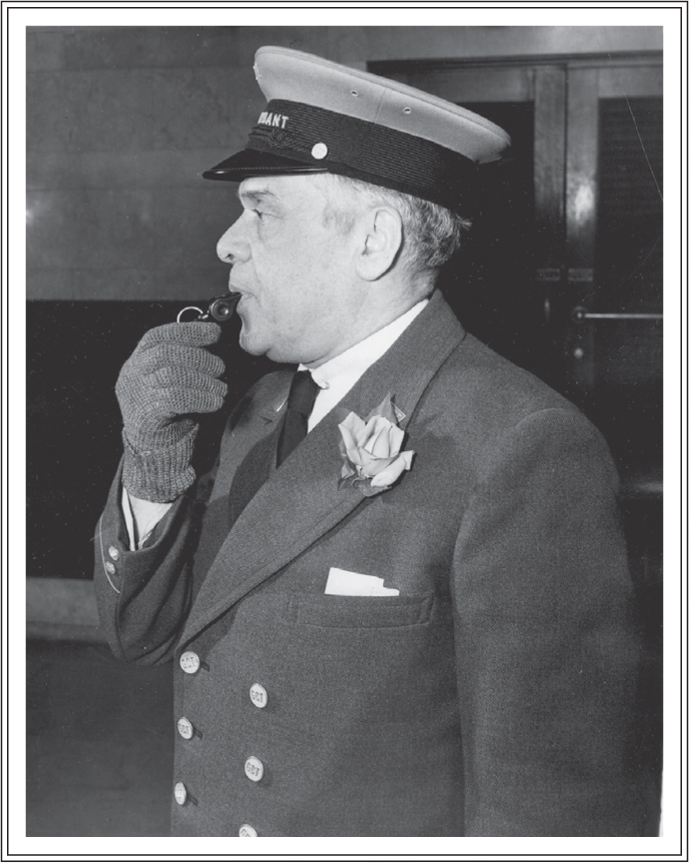

By 1940, Chief James H. Williams, sixty-one, had worked for thirty-seven years at Grand Central Terminal. With his iconic whistle, he directed some 500 black Red Caps, “who handle 85,000 pieces of baggage each month,” throughout the forty-eight-acre gateway to a continent. ACME Press Photo.

“I just stand there blowing my whistle and answering questions,” he had said with good-natured modesty not so long before. “And sort of checking up on the boys, too. . . . I can close my eyes and tell from the sound how many bags are on their trucks.”12 He confessed he was looking forward to retiring at seventy, but he was summoned from his job prematurely.

On May 4, 1948, Grand Central awakened to a chilly but clear morning. Red Cap porters rushed to and from the platforms as usual, heaving luggage through the station with commuters in tow. They bustled through the station’s ramps and halls to the taxis pulling up at “Sugar Hill” on Vanderbilt Avenue, on Lexington Avenue, and on 42nd Street. At about 11:10 a.m., several miles uptown in the Bronx, Chief Williams died quietly at Morrisania Hospital, where he had been for five days.

Wesley made the funeral arrangements for his father through the undertaking firm of Levy and Delany, co-owned by a family friend, Samuel R. Delany, who had been one of his father’s station captains. The funeral took place at Grace Congregational Church in Harlem. The Chief’s surviving family included his second wife, Martha; his three brothers, Charles, Francis, and Richard; his two sisters, Ella and Lena, both still running the Colored Mission on West 131st Street; his two surviving sons, Wesley and Pierre; and his two daughters, Gertrude and Katherine. Neither of his daughters had had children, but his sons had sired several.

Wesley arranged for a multiple plot at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. Buried there, James H. Williams was reunited with his first wife, Lucy; their son James Leroy “Roy” Williams; and Wesley’s first wife, Margaret. Williams’s older brother, Charles Wesley Williams, would die just a few months later, in November 1948, and be buried at Woodlawn with his wife, Jennie. Wesley himself, when he died, would be cremated and interred nearby with his soulmate Francine Musorofiti, whom he had met while assigned on Broome Street in Little Italy. Though Woodlawn Cemetery was geographically convenient to both Harlem and the Bronx, a good number of the immediate family were buried at the Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn. A single marker locates the latter plot, inscribed “To My Beloved Husband Lloyd M. Cofer Jr., aged 21 years, from Ella W. Cofer 1881–1967.” Williams’s sister had never remarried.

In the wake of Williams’s death, several obituaries remembered him principally for his giving jobs to college-going young men. Though he was not the first Red Cap porter, he broke the color barrier at the world’s most prominent railway station. His hiring signaled an inflection point for the burgeoning black middle class in urban centers connected by trains. His promotion in 1909 to chief attendant positioned him as the preeminent Red Cap in the country—a position that he undertook as a calling. “If an institution is the shadow of a man,” an editorial read, “Mr. Williams cast a shadow of his personality over the Red Caps he carefully selected, trained and supervised.”13 For almost half a century, he encouraged hundreds of young black men to work their way through college as Red Caps. Not a few of them came to personify the professional diversity that was at the heart of Williams’s mission: to foster the growth of successful African-American men in New York and beyond.

In the first quarter of the twentieth century, anticipating the emergence of a formal railroad labor union, he was a principal organizer, protagonist, and arbiter of black railroad workers. As Grand Central was a city within the city, he was the architect of redcapping that black college students came to regard as an institution within an institution. Abram Hill noted the Chief’s great pride that his department was a higher employer of college men than any other in Grand Central.

Many in Harlem regarded Chief Williams as a community hero. Born to parents who were themselves born in slavery, he was one of the last graduates of New York City’s race-based Colored School system, whose teachers strove to inculcate their pupils with a moral purpose to uplift the race from systemic adversity. He numbered in the first manifest wave of African-American residents to Harlem. He was one of the earliest officers of Manhattan Lodge no. 45, the largest black fraternal lodge in the country of the Colored Elks, and one of the founding signatories of its newly chartered body. He was among the first black residents to buy a home in Strivers’ Row, and a principal notable of Celebrity House, as Rockefeller’s experimental Paul Laurence Dunbar Apartments were colloquially known.

It was no small matter of pride to Chief Williams that his assistant chief, Jesse Battle—a cherished friend of the entire Williams family—became New York City’s first African-American police officer. Bolstered by Battle’s example, his son Wesley would become Manhattan’s first black fireman and the city’s first black fire department officer. Williams’s often-cited intimate connection with these two historic figures, who broke the glass ceiling of the city’s racially restrictive hiring and promotion practices, inspired numerous young black students countrywide. Many of these young men were students, for whom inhospitable college dormitories made the Williams’s home a vitally welcoming refuge.

Socially, Chief Williams cultivated personal relations with the societal and artistic elite both white and black. The press often reflected esteem for his diligent activism and philanthropy, notably on behalf of the NAACP, the Urban League, and his diligent support for black soldiers during two world wars.

Chief Williams played a conspicuous role in recreation and athletics. In the 1910s, his Grand Central Terminal Baseball Club made him a key participant in the evolution of the competitive “black nines” of semiprofessional Negro League baseball, as it did similarly in the 1920s, with his “black fives” team of professional basketball. Despite having created Red Cap baseball, basketball, and bridge teams under Grand Central Terminal’s banner, Williams doesn’t appear to have organized a tennis team, an activity where he nevertheless made an outstanding impact with the eponymous Williams Cup. Sponsored by the Grand Central Red Caps, the silver Tiffany trophy was awarded by the American Tennis Association, the country’s oldest active historically black athletic organization, as one of its highest honors for three decades. Though its potency lessened as black professional tennis stars, such as Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe, broke through the sport’s racial barriers, the prize nevertheless enriched the legacy of black American tennis history.

Williams had established and promoted the Grand Central Red Cap Orchestra, two Grand Central Red Cap Quartets, and a choir, all of which were influential in public social life within and beyond Harlem through live, recorded, and radio broadcast performances. The artistic integrity of the orchestra and quartet also contributed to making Grand Central an uplifting holiday destination where New York locals and tourists enjoyed caroling for years.

As a public figure, Williams promoted enterprises that fostered race pride, and that also influenced interracial alliances to affect social reform. Through his position, he created a gateway that produced such agents of social change as Lester Granger of the Urban League, the activist and performer Paul Robeson, the pastor and U.S. congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., the civil rights leader and jurist Raymond Pace Alexander, the journalist and politician Earl Brown, and the Broadway star and booking agent Richard Huey.

In the travel industry, his famously disciplined Red Cap porters imbued a distinct humanity to the American experience of railroad travel. “We can’t run Grand Central without the Chief,” the supervisor of the station’s Travelers Aid Society had said some years prior to Williams’s death. “He’s as much a part of the place as the 20th Century.”14 Her comparison of the Chief to one of the world’s most famous railroad trains was apt, evoking how essential the system of Red Cap porters were to the function and experience of the Terminal City and of railroad travel itself in the first half of the twentieth century.

In the mid-1940s, the Red Caps at Grand Central numbered about three hundred. In his book about the terminal, David Marshall disabused readers of “the minstrel-show dialect imputed to them” quite unfairly in the press. “Their grammar is not too bad; for New York, it’s better than average,” he wrote. “Their diction is good, sound, working-class diction.”15 Marshall also admitted “that the red cap is a trained manager who takes you in charge as well as your luggage; who steers you the right way by every possible short cut, and gets you through the gate before the gateman slams it shut; who talks as well as any gentleman’s gentleman should; who cheers you with a flashing smile, bows like a nobleman, and—pays you the tribute of overestimating your importance.”16

In 1952, fourteen years after Chief Williams’s death, former New York State governor Herbert H. Lehman wrote a letter of regard to Wesley Williams, on Wesley’s retirement from the fire department: “I had the privilege of your father’s friendship for a great many years, and I know that I first met you through him when he introduced us at the Grand Central Station just before you were appointed as Battalion Chief. He, too, was a very fine man.”17

In popular culture, countless film, stage, and literary works reflect the legacy of Williams. Whether they appear incidentally or are featured prominently, black Red Cap porters are ubiquitous in depictions of American railroad stations. They populate scenes of diverse cinematic fare that either employ or evoke Grand Central Terminal. In Roy Mack’s 1932 musical short Smash Your Baggage, dancers from Harlem’s Small’s Paradise nightclub portray travelers and porters in breathless abandon at Grand Central. Raoul Walsh’s Going Hollywood, a big-budget, feature-length 1933 musical starring Marion Davies and Bing Crosby, features a large dance number at the terminal.

We see Red Caps or the terminal in The Band Wagon (1953), starring Fred Astaire, and even in Alfred Hitchcock’s suspense thrillers Strangers on a Train (1951) and North by Northwest (1959). In 1932 the dramatists Ben Hecht (who later collaborated with Louis Armstrong on the song “Red Cap”) and Charles MacArthur wrote a hit Broadway farce, Twentieth Century. In creating a character of the chief of ten Grand Central Red Caps, played by actor Frank Badham, they evoked Williams.

In 1978, thirty years after Chief Williams’s death, a musical version of the Hecht/MacArthur play, On the Twentieth Century, afforded an ensemble of four black Red Cap porters a nightly Broadway showstopper called “Life Is Like a Train.” Joseph Wise, one of the ensemble, understood the palpable connection of American railroad history to his own African-American heritage. He knew the Red Cap occupation once gave manifold opportunities to African Americans, and now it gave ineffable opportunities to four aspiring black performers within the narrow casting parameters of a period theater piece. Ironically, the show’s nontraditional casting of the porters extended less liberally to other principal roles. In February 2015 the musical was revived, and a promotional poster portrayed the Red Caps as three whites—a fourth one in the cast, who was black, was not shown. The omission was telling. “I think it is a missed opportunity,” Wise wrote in a blog at the time. Indeed, it was telling of how much Chief Williams’s mission to eradicate the color bar remains ongoing.

By the time Williams died in 1948, his moniker “Chief Williams” had been eclipsed by his son, Wesley, who had become Battalion Chief Williams of the fire department ten years earlier. But the railroad itself was losing purchase in the modern age as well. Travelers increasingly preferred the romantic expediency of flying, or surrendered to the lure of highways and automobiles. And as they did, the pulse of the great railroad station gradually and naturally waned.

The Red Caps have disappeared from Grand Central Terminal, although they exist in some railroad stations elsewhere in the country with greatly modified job descriptions. From our twenty-first-century perspective, we cherish the grand Beaux-Arts complex as an architectural achievement, its preservation championed by such celebrities as the late Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. But the intersecting narratives of Grand Central and Harlem’s vibrant African-American community are woefully incomplete without attention to the contribution of James H. Williams. He had a keen vantage point of the proverbial passing parade, maintaining a sure footing in the antipodes of downtown Grand Central Terminal and uptown Harlem. More than just witnessing history, Williams had direct agency in the unfolding histories of each, and to both he demonstrated lifelong constancy.

James H. Williams’s story is especially significant today, as the challenge of acknowledging and mending America’s racially divided past often triggers defensiveness or engenders bitterness. His life chronicles how a representative body of African-American workers proactively countered Jim Crow, which pervaded even the most resplendent public halls of the nation’s most enlightened modern city. Not through brawn and stamina alone, but rather with persistent fellowship, ingenuity, and grace, Williams and his men remained determined to attain their North Star in even a painted-on vault of heaven.