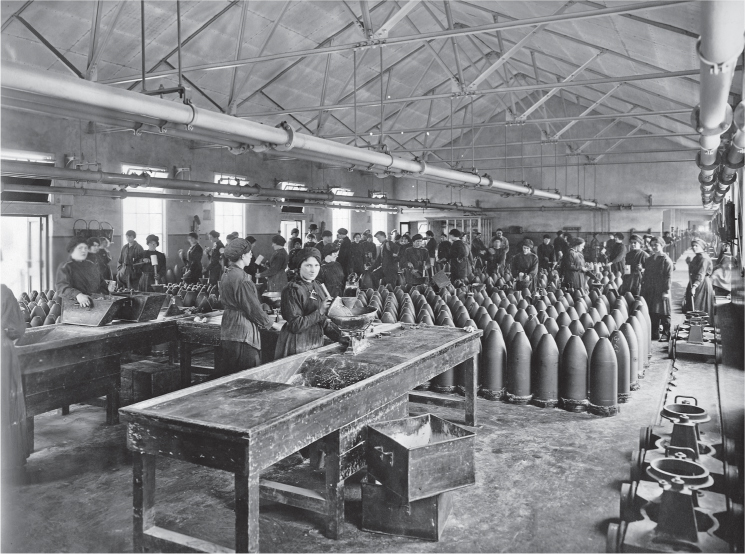

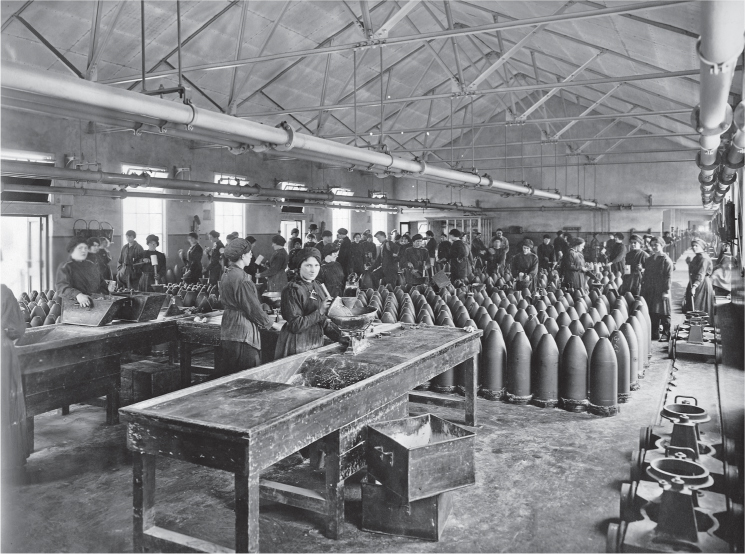

An interior view of the National Filling Factory: women weighing explosives for the shells. (LCM)

Although most Britons supported their country’s entry into the First World War, there was no shortage of voices opposing the conflict. Many members of the Independent Labour Party criticised Britain’s involvement. So too did most Quakers, along with some Baptists and Methodists, as well as a few members of the Church of England. Some critics of the war believed that ordinary people had no stake in a conflict being fought to defend the financial interests of the rich and powerful. Others suggested that killing on the battlefield could never be reconciled with the Christian command to ‘love thy neighbour as thyself’. Such arguments were often combined, perhaps no matter for surprise, given that the development of socialism in Britain had been shaped as much by Methodism as Marx.

Lancaster did not have a strong tradition of labour radicalism before the First World War. No Labour candidate stood for election in the town until 1922, when the Party’s unsuccessful candidate was Fenner Brockway, who had after 1914 been a prominent opponent of the war and founder of the No-Conscription Fellowship. Some of Britain’s big industrial cities witnessed considerable industrial unrest after 1914, often fuelled by resentment over poor working conditions and long hours, which were an inevitable consequence of the need to keep supplies flowing to the army. The potential impact of the conflict on Lancaster’s economy certainly raised fears during the early days of the war that mass unemployment could lead to suffering and poverty. In the event, the economic impact proved to be less severe than anticipated, in large part due to the rapid growth of the munitions industry.

An interior view of the National Filling Factory: women weighing explosives for the shells. (LCM)

The conditions faced by the mainly female workforce in some munitions factories were often very poor. The massive explosion at White Lund in 1917 showed the perils of working in armaments production, even though just ten people died, but the real dangers could be more insidious. Sixteen-year-old Isabella Clarke, who worked at White Lund, later recalled how one of her friends died from the toxic effects of loading 9.2in shells with gas. Despite the poor conditions, serious labour unrest was rare in Lancaster, although in spring 1916 thirty men left their work in a shipbreaking yard in neighbouring Morecambe, in breach of the Munitions of War Act. They soon returned, though, when told by a local solicitor that their action was illegal. The Lancaster Observer praised the men for their common sense, contrasting their behaviour with that of workers in some other towns and cities, where protests often took on a more militant character.

Few people in Lancaster publicly questioned whether Britain was right to go to war in the summer of 1914. Although the town’s response to news of the conflict was muted, the public mood was not one calculated to encourage open expressions of outright dissent. As soldiers departed for the Front, and the casualty lists mounted, any expression of disagreement with the war could easily be seen as unpatriotic at a time of national crisis.

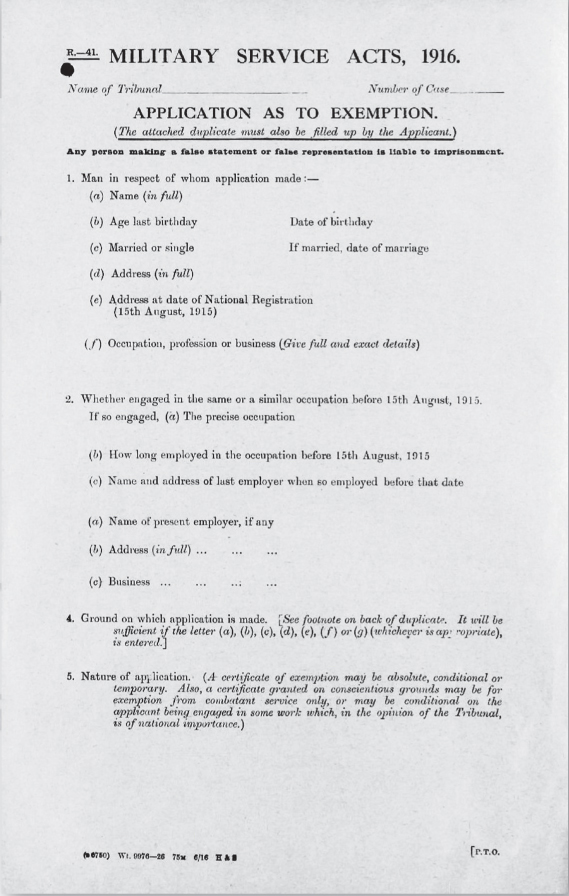

The recruitment campaigns that took place in Lancaster throughout 1915 were calculated to bring social pressure to bear on all those who had not already enlisted. It was nevertheless still possible for men who did not want to fight to continue with their normal peacetime occupation (although the introduction of the Derby Scheme in the autumn of 1915 increased the pressure). The passing of the Military Service Act in January 1916 transformed the situation. The introduction of conscription was bound to prove controversial for many in Britain, given the lack of a tradition of compulsory military service, although only one minister, Sir John Simon, resigned from the Cabinet in protest. The Act provided the foundation for the conscription of younger unmarried men, and established a series of Military Service Tribunals to hear appeals from those who believed they should not be called up, typically on the grounds of domestic hardship or because they were engaged in work of national importance. But – after considerable debate in Parliament – the government also agreed on a clause that would allow men to appeal against military service on the grounds of conscience. Men who believed they should be exempted from joining the army, for whatever reason, had to fill out an exemption form before their case was heard by one of the tribunals.

Around 17,000 men from across Britain eventually became conscientious objectors. Most agreed to undertake some form of alternative service, perhaps entering the Royal Army Medical Corps, or joining the Friends Ambulance Unit (founded by Quakers although formally independent from the Society of Friends). A few thousand ‘absolutists’ refused to carry out any work that could be seen as supporting the war effort and were often imprisoned as a result. Some were handed over to the military, where they often faced court-martial, and a few were even threatened with execution for refusing to obey orders. The county of Lancashire produced nearly 2,000 conscientious objectors. Most came from the large urban areas in the south of the country. Surprisingly few came from the towns of Lancaster and Morecambe, though a significant number did come from the villages that stretched up the Lune Valley. The surviving records give a fascinating insight both into the way the local tribunals operated and the attitudes of the men who appeared before them.

The Military Service Act allowed for possible grounds for exemption. (MJH)

Only a small number of men who appeared before tribunals in Lancaster and the surrounding areas sought exemption on grounds of conscience. This may in part have been because they believed they were more likely to be successful if they claimed to be doing work of national importance. It may also have been that they were fearful of the hostile reaction to conscientious objectors across Britain. Some editorial notes that appeared in the Lancaster Observer towards the end of February 1916 give a good sense of the hostility of local opinion towards conscientious objectors. The paper noted that ‘Only men can defeat our malignant foe … Neither religious scruples, nor business exigencies, nor parental ties afford the excuse for standing back while others do the work.’ It went on to suggest that any who sought exemption on whatever grounds ‘will be social lepers, abhorred and abused as cowards’. Men who appealed to the tribunals for exemption from military service on grounds of conscience knew that they were unlikely to be treated with much sympathy.

It is easy to understand the fears both of those who went to war and the families they left behind. It is important to remember, too, that the departure of thousands of men for the Front created enormous economic disruption at home. The situation was particularly acute for small businesses. In September 1916, the Lancaster Borough Tribunal heard appeals on behalf of a number of young men employed in local building and joinery businesses, which found it almost impossible to operate without skilled labour. The same Tribunal also heard an appeal from a ‘basketmaker’ who promised to teach his craft to others if he was allowed to remain at home. The results of such cases were not always predictable. Many men were ordered to join up as soon as possible, even if it would bring hardship to their family, but others, like a Lancaster piano builder, were for some reason given exemption.

Among the businesses hardest hit by the introduction of conscription in 1916 were family farms. The tribunals often reacted sceptically to claims that agricultural work would be disrupted if the younger men were sent into the army. This may have reflected the fact that some tribunal members did not really understand farming. It may also have been that they suspected farmers were trying to protect their sons from having to fight. This was sometimes true. One farmer who worked land in the Lune Valley dismissed his paid workers so that he could claim his own sons were indispensible to his business. The reluctance of farming families to free up labour for the war effort created considerable resentment in Lancaster. The town’s civil leaders repeatedly called on the local villages to follow the example of their urban neighbours by sending as many men as possible into the army.

A sample blank exemption form. (MJH)

The local newspapers reported on the deliberations of the Military Service Tribunals. (MJH)

The challenges likely to face would-be conscientious objectors became clear on 8 March 1916, when the Lunesdale Tribunal first met in the village of Hornby, a few miles north-east of Lancaster. Among the large number of claims for exemption from military service were ten from conscientious objectors. Three brothers from one farming family sought exemption on the grounds that killing another human being was contrary to their beliefs. Their case attracted a good deal of national attention when it transpired their father was actually a tribunal member! One applicant was asked whether he would defend his girlfriend if a German soldier ‘threw her down, and attempted to ravish her’. Another was told to explain how he would react if he saw ‘a German crucifying a child on a door’ (reports of such things happening in Belgium had long circulated in the British press). A third was quizzed about his actions should he witness his mother being killed. When the men before the Tribunal responded uncertainly to such questions, or denied outright that they would ever use force, the Tribunal Chairman roundly condemned them for lack of patriotism: ‘How a man can talk this rubbish you conscientious objectors put before us I don’t know.’ The contemptuous tone of the questioning was serious enough to be raised in Parliament shortly after.

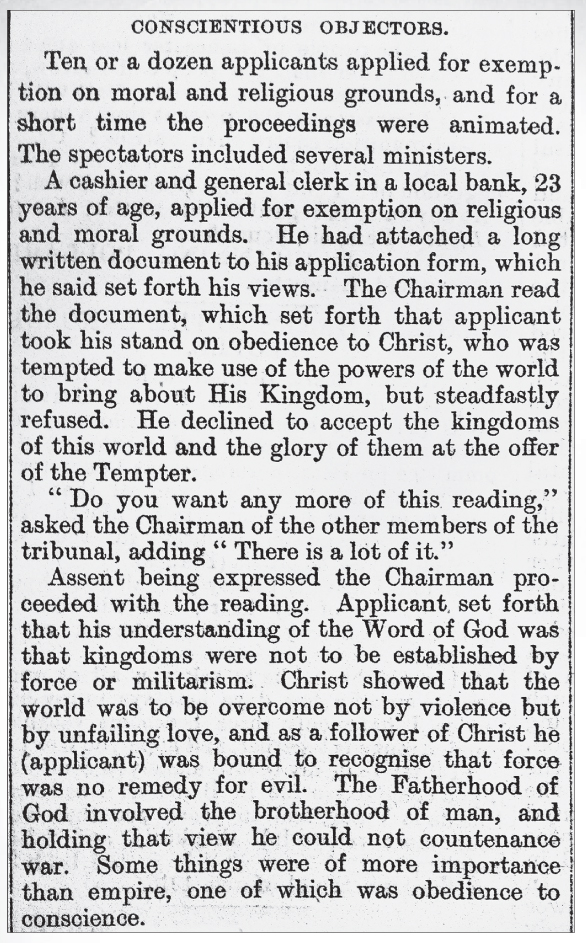

A few days later, it was the turn of the Lancaster Borough Tribunal to hear appeals from men who objected to conscription on grounds of conscience. The first man to be heard was 23-year-old Norman Witham, a cashier in a local bank, who presented a long document setting out his belief in ‘the brotherhood of man’. His case was not helped by the fact that he was a Wesleyan Methodist – the Wesleyans generally supported the war, although a local Minister was Honourable Secretary of the Lancaster branch of the No-Conscription Fellowship – and Witham was closely questioned by the Chairman and the Military Representative about his understanding of the New Testament. He was also asked whether he would act to defend his sister if she were attacked. The case of Witham was followed by a number of others, including a schoolteacher who said that war was contrary to ‘religion and humanity’, and another young Wesleyan who argued that war represented a ‘denial of Christianity’. A 38-year-old ‘artist-designer’ said that he thought war was ‘of the devil’ but acknowledged he attended no church or chapel. Much of the questioning was tinged with sarcasm. The Military Representative noted scathingly to one applicant that ‘You can train your conscience … to do almost anything’. Many cases were nevertheless accepted, and the applicants were given exemption from combatant service (and typically required to carry out work of national importance or join an organisation like the Friends Ambulance Unit). A few were not so lucky. The press report of the Tribunal hearing ends with a laconic statement that ‘Later, a painter (24) applied for exemption on the grounds that he strongly objected to killing, but the application was refused.’

The tribunals in and around Lancaster continued to be busy over the next few months. In April, the Lonsdale Appeal Tribunal – which heard appeals from the local tribunals – met at Lancaster Castle to hear numerous cases including those of a number of conscientious objectors. One case was refused altogether. Other conscientious objectors were given non-combatant service, though often only after suffering harsh remarks that they preferred ‘a comfortable occupation at home’, with the clear hint that they were using claims of conscience simply to avoid danger. Some of the men were reprimanded for making speeches rather than giving evidence (tribunal members seldom looked kindly on those who sought to turn the proceedings into a debating chamber). Many were asked the familiar question about whether they would use force to protect family members – and if so how they could justify seeking exemption from military service. The cases before the Lonsdale Tribunal show that conscientious objectors continued to be drawn disproportionately from rural areas outside Lancaster. Voluntary enlistment in north Lancashire had been lower in the villages throughout 1914 and 1915, probably because it was so difficult to spare young men from small family farms. The recruiting rallies that had taken place in the bigger towns in any case seemed remote in rural areas where transport was poor and the communities close-knit. Religious observance was also higher in the countryside. When conscription was introduced, it was always likely that many conscientious objectors would come from the countryside, rather than from Lancaster with its strong military presence.

Most men who sought exemption did so because of the hardship it would cause their employers or families, but a small number refused to fight on grounds of conscience. Many conscientious objectors were ready to undertake some kind of alternative work. A few were not and were sent to prison. Although Lancashire produced a large number of conscientious objectors, only a small number came from the town of Lancaster itself.

The case of a 23-year-old cashier at a local bank, reported in the Lancaster Observer on 17 March 1916, offers an example of the moral and religious reasoning presented to the tribunal. (MJH)

Young men who belonged to the Society of Friends generally found it straightforward to persuade tribunals to offer them exemption from combatant service given that the Quaker views on war were well-known. Most Quakers, like 32-year-old Joseph Muschamp, an undertaker who lived on Denmark Street, claimed absolute exemption from military service, but were only offered conditional exemption, typically requiring them to serve with the Friends Ambulance Unit. The Quakers who really fell foul of the Military Service Act were those who refused to undertake any kind of work that could be seen as supporting the war effort. The experiences of the two Walmesley brothers, Cyril and Alwyne, who were educated in Lancaster and later at a Quaker boarding school, illustrates how the treatment of a conscientious objector varied according to the kind of exemption they sought. Cyril joined a Friends War Victim Relief Committee unit in 1915, before the Military Service Act was introduced, and when his case was heard in absentia in February 1916 he was given exemption from combatant service on the grounds that he was already doing valuable work. He was later praised in the Lancaster Guardian for ‘doing very efficient work in repairing a hospital damaged by the German bombardment’ while ‘living in considerable danger’.

Henry Alty, a joiner from Pilling near Lancaster, faced a court martial for refusing to fight. His case was raised in Parliament, where it was claimed that he had been ill-treated, ‘prodded behind with a sharp instrument until he collapsed on the floor, and … was then dragged some considerable distance and afterwards thrown on top of the barrow.’

The case of Alwyne Walmesley was very different. Alwyne was teaching in Cambridge when he appeared before the local tribunal there, which gave him exemption from combatant service, but required him to join the Friends Ambulance Unit (FAU). A few months later he asked for the case to be reopened, resigning from the Unit citing grounds of conscience, but the authorities refused to reconsider his position. He was subsequently arrested in Lancaster in the summer of 1917, and brought before the local Bench, where he claimed that the FAU was, despite its humanitarian ethos, still a military service. He was sentenced to six months hard labour in Wormwood Scrubs.

The regime in Wormwood Scrubs was notoriously harsh. Some conscientious objectors imprisoned there later recalled that they often contemplated suicide. Although Alwyne’s objections to serving with the FAU were accepted as genuine when he appeared before a tribunal held at the prison, he was once again arrested following his release early in 1918, telling the Court in Lancaster that his views had become still firmer during his time in prison. Alwyne was taken to Park Hall Camp near Oswestry, where he faced a court martial, at which he repeated his claim that only a reinvigoration of the ‘spiritual life of the individual’ could prevent civilisation ‘from plunging into that anarchy to which it is clearly advancing’. He was throughout his long ordeal astonishingly resilient. He praised the chaplains who ministered to prisoners at the Scrubs, and while at Oswestry recalled his time in prison in London as ‘in a peculiar sense a happy period … the only punishment is the want of self-expression and the feeling of the utter stupidity and wastefulness of the whole process.’

Spencer Ellwood Barrow was an architect and honorary treasurer of the Royal Lancaster Infirmary (RLI). Although he was a member of the Society of Friends, he enlisted in September 1914 as he felt that facing German aggression was more important than his religious beliefs. He died on 16 November 1915 from wounds received in action in May 1915 at Frezenberg. He is buried in Scotforth Cemetery and there is a memorial window to him in the RLI.

The names of conscientious objectors who appeared before the tribunals were not usually recorded in the published proceedings, meaning that it is sometimes hard to identify individuals, although recent research has made it possible to identify a number of them. Almost all conscientious objectors who appeared before tribunals in Lancaster and the surrounding villages based their claim on their religious views (though in Lancaster itself a significant number acknowledged that they did not regularly attend Church or Chapel). As well as Quakers, there were Wesleyans and Primitive Methodists, Baptists and Congregationalists. A rather different attitude towards conscription was in evidence at the Conference of the Miners Federation of Great Britain, which met in Lancaster a few weeks after the passing of the Military Service Act. The delegates passed a motion opposing ‘the spirit of conscription’, and expressed determination to prevent any extension to the groups of men eligible for call-up. They also discussed whether to begin ‘agitation’ for the Act’s repeal. The idea that the First World War was being fought with the blood of the workers was not uncommon in Britain, even if it was seldom heard at the tribunals that met in and around Lancaster, where labour militancy was traditionally lower than in the big cities of south Lancashire.

Most men who sought certificates of exemption from the tribunals were not conscientious objectors. They instead sought exemption on other grounds, most often claiming that recruitment into the army would take them away from work of national importance, or leave their family destitute. Such claims were scrutinised carefully by the tribunals, and often turned down, much to the disgust of the applicants. The rate of rejection became higher as the war progressed, and the need for soldiers greater than ever, and few claimants ever gained more than a few weeks’ grace to put their affairs in order. The tribunals in and around Lancaster closely interrogated those seeking exemption. Although the tone of the questioning was seldom as harsh as it was with conscientious objectors, many tribunal members clearly believed that most men seeking to avoid military service were motivated by a desire to put their private interest over the good of their country.

Some of the claims that came before the tribunals received particularly short shrift. The Lancaster Borough Tribunal that met in early May 1916 considered a request from a local hairdresser for an extension to his certificate of exemption, which had been issued some weeks earlier, in order to allow him to put his affairs in order before joining up. He told the Tribunal that several munitions factories had opened near his premises, and asked what was to be done for the workers who crowded his shop. The Military Representative tersely replied that ‘we must all grow beards’. At the same Tribunal, a clogger argued in vain that his work was of national importance, given that many poorer residents could not afford expensive leather shoes. A local baker argued without success that his son should be allowed to continue working in the business since he did much of the lifting and carrying.

Many claims for exemption on grounds of work of national priority came from farmers in the countryside around Lancaster. One farmer sought exemption for his two sons on the grounds that he needed them to work the land, but was told he could keep just one of them at home (‘It’s cruel,’ a member of the public called out). The Lancaster Rural District Tribunal heard a particularly large number of cases. Many farmers described at length how they could not get labour to cover for sons called up for service. The results varied from case to case, but in general only a temporary exemption was offered, in order to allow the farmer to find other labour. The fact that so many appeals for exemption came from men who worked in the family business meant that tribunal members often suspected that emotion rather than the needs of the farm was the real motive behind an application for exemption. Nor were they generally sympathetic to those who said their business would be ruined. Although most claimants who came before the tribunals did not argue that war was wrong, or that they objected to taking a human life, many of them were in effect dissenting from the state’s claim that it had the right to mobilise the population for total war. Such sentiments were unlikely to find favour at a time of total war.

Many claims for exemption were sponsored by major businesses in Lancaster. In March 1916, the works manager at Waring and Gillow, which had by now been converted from manufacturing fine furniture to building aircraft wings, was ordered to appear before the Lancaster Borough Tribunal to explain why the company laid off older men but kept on younger men who would otherwise be eligible for military service. The Tribunal accepted the explanation that the firm needed to keep its ‘best men’ in order to operate efficiently, but made it clear that the company should whenever possible release younger men. Lord Ashton also protested vigorously from time to time against demands that more of his workers should be sent into the forces, pointing out that his factories would then be forced to close, putting thousands of women and older men out of work. Lancaster Borough Council similarly sought exemption for large numbers of employees, a move that caused some embarrassment for councillors who sat on the tribunals. Leaders of these organisations were naturally careful to pronounce their support for the war effort (businessmen like Ashton had indeed been vocal in encouraging their workers to enlist during the years of voluntary recruitment). But they were also intensely aware of the financial and operational consequences of conscription for their businesses as it shrunk the workforce still further. The introduction of conscription was not only a challenge for those whose consciences led them to refuse to take up arms.

There were of course many other ways in which individuals could behave in a way that disrupted the war effort, though this was most often the result of putting personal interests ahead of the wider national interest, rather than a deliberate act of dissent. The Munitions Tribunal in Lancaster met regularly to hear the case of workers whose behaviour could undermine the effectiveness of local munitions factories. One tribunal session held early in 1918 heard cases ranging from gambling to falling asleep ‘on the job’. Other sessions heard cases concerning absenteeism or rowdy behaviour. The regular military tribunals often expressed irritation that many young men were ‘sheltering’ in munitions factories, enjoying well-paid employment, rather than joining the army (a strategy that some men certainly followed). The local police in Lancaster also had to deal with soldiers who went AWOL, either in a deliberate attempt to escape the rigours of military life, or as a consequence of too much alcohol. Some Lancastrians were brought before the Bench for hoarding food. Farmers were prosecuted for refusing to comply with instructions from the War Agricultural Committee. Such examples of anti-social behaviour received considerable censure in the local press. The Lancaster Observer vented its spleen against a cyclist who, when stopped for riding without a front light, said that he was a munitions worker and would deliberately stay away from work in protest. The magistrates took a predictably unsympathetic view of his behaviour when deciding on the appropriate penalty.

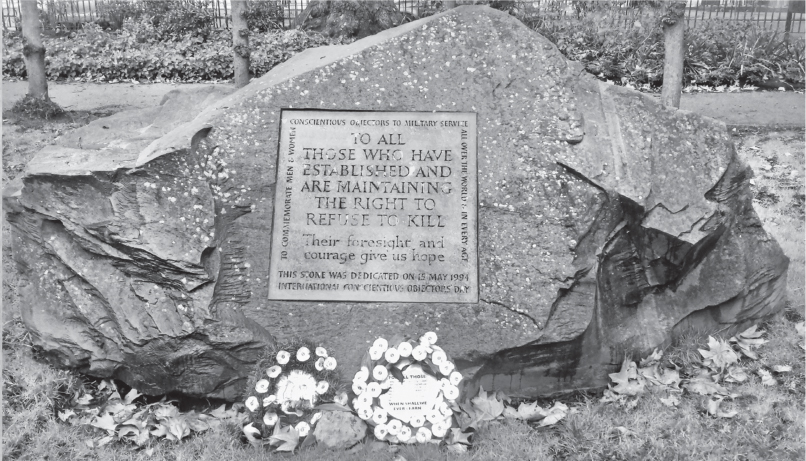

The Stone of Remembrance in Tavistock Gardens, London, was unveiled in 1994. (CPB)

North Lancashire was not a hotbed of conscientious objectors. The town’s proud military heritage probably created social pressure that made it hard for young men to refuse to fight. Nor did the tribunals in Lancaster and the surrounding areas behave with particular harshness. ‘Conchies’ were treated with disdain rather than cruelty. Yet it did take a particular kind of courage to refuse to join up. It is still not clear exactly how many men from Lancaster and the surrounding towns and cities refused to undertake combatant service. The reports in the local press suggest that there were probably a greater number of conscientious objectors than is realised today. Most of these men have faded from history – although there is now a memorial to them in London. Their experiences, like those of the soldiers who fought in the trenches of France, form part of the human tapestry changed forever by the First World War.