At some point in 1975, during the Grateful Dead’s hiatus, something happened that would forever change late-night television: Saturday Night Live. Groundbreaking in its unflinching use of satire and the unapologetic way that it made fun of sensitive current events—on live television, for a national audience—NBC’s new sketch comedy show became an instant smash, and its cast (which, during that inaugural season, included John Belushi, Dan Aykroyd, Chevy Chase, and Gilda Radner) became instant SNL stars. I became an instant fan. I never watched much television, but I used to love to get stoned and turn on SNL. They had those fake commercials that would get me every time. I just loved that.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, one of SNL’s top writers, Tom Davis, was a Deadhead. At some point, after Davis and I became friends, I congratulated him on winning an Emmy Award. It was for Outstanding Writing in a Comedy Variety or Music Special—specifically, for his work on NBC’s December 8, 1977, Paul Simon Special.

I looked at him and said, “You know, I never had an Emmy.” Without missing a beat, he said, “You know, I never had a gold record.” The logical conclusion was that we should fix that by trading awards. Tit for tat. We were just being silly, but we went with it. So on the bookshelf in my living room now, I have an Emmy Award for an NBC special. And, somewhere, Davis was able to hang a gold album for American Beauty.

I should also mention, as a footnote, that Davis’s writing and acting partner was Al Franken, who is now a U.S. senator (D.) for Minnesota—and a Deadhead. “We are everywhere.”

It may not be immediately obvious, but there are some undeniable parallels—or, at least, similarities—between the Grateful Dead and SNL. We both constantly took great risks, which sometimes led to train wrecks but also led us to unprecedented triumphs. We both were seen as renegade heroes of counterculture, rebellious artists that prided ourselves on challenging the status quo. We both were underdogs from the underground that somehow managed to embed ourselves in at least one home in just about any given neighborhood in America. And, behind the scenes, both the cast of SNL and the band members of the Grateful Dead were legendary party animals, ravenous for drugs and danger … and dangerous drugs. It seemed like both camps would get along.

Still, it was a bit of a shock—and a total thrill—when I found out that we were invited to be the musical guests for one of the episodes. Not everyone in the band shared my enthusiasm. Jerry wasn’t into it. I’m not sure that Phil was, either. They had their reasons, whatever they were, but Mickey sided with me and we managed to convince them to do it. We ended up playing SNL twice over the next couple of years, but our debut was on November 11, 1978, with Buck Henry hosting. We performed “Casey Jones,” “I Need a Miracle,” and “Good Loving” and we actually managed to pull it off, bucking the trend of us messing up the big ones.

For me, the best part was getting to have a cameo in one of the comedy sketches with my favorite cast member: John Belushi. I had the simplest part. I played “Cliff Morton from Bakersfield,” and I got to drink Budweiser on live national TV. People ask me and, yes, it was real Budweiser. Still didn’t calm my nerves. But the sketch worked and the audience laughed. It didn’t launch my career in comedy, per se, but it did lead to a fantastic and treasured friendship with Belushi that would get us into some wild adventures in the days to come. Belushi died in 1982, darn it, but boy did we ever have high times ’til then.

I hung out with Belushi whenever I could, especially when the band had shows in New York. We’d kick it at his place, or his office, or wherever we could find trouble. I have many different memories of John Belushi, but the one I’m about to tell you is my absolute favorite.

The Grateful Dead had a three-night stand at the Capitol Theater—not the restored one in Port Chester, New York, where we played a number of historic shows as well, but the one on the other side of the city, in Passaic, New Jersey—beginning on March 30, 1980. We weren’t on tour, and I think we probably booked the gigs as a stand-alone run because we were going to be in New York anyway, for our second appearance on SNL, on April 5, 1980.

By that point, Belushi had already left the cast of SNL to concentrate on film. But we decided to pull off some real life “sketchy comedy,” so I met up with him a few days before the shows and we immediately started getting into trouble. And trouble with Belushi almost always meant cocaine. We went on a bit of a bender, just raving the nights away. The day before our opening night, he really wanted me to hear this demo tape of a radio sketch that he was working on for a National Lampoon show. The setup was that he played a drugged-out hitchhiker who was trying to get to a Grateful Dead concert to see Pigpen play with Janis Joplin. He wasn’t aware that the year was 1980. It was a classic Belushi sketch. All in the delivery, perhaps.

He insisted that we go down to the studio so that we could listen to the playback. But when we got there, the producer was busy in the control room and we had to wait. As you know by now, “waiting”—for either of us—meant imminent trouble. Belushi waltzed right into the main recording room and started stuffing all these expensive microphones into all of his pockets until he was just overflowing with them in a really cartoonish way. “See how easy it is, Billy? Want a brand-new microphone?” He put them back, but not until after I had a good laugh. Pure slapstick.

After that, we went back to Belushi’s office and continued to party. In between blowing lines of cocaine were fits of laughter. Suddenly, I realized that it was approaching afternoon—on the day of the show! We had been raving until the night had passed back into the day. I started getting paranoid. How would I have enough energy to make it through the show? This was night one and I owed the audience my best. I needed to get some sleep and drag my ass over to soundcheck somehow.

But Belushi had a different idea. He took me to a Russian bathhouse that, in those days, were popular places for men to go and get massages and rejuvenate, kind of like what spas are for women nowadays. Belushi was a regular at a few of them in the city. When we got there, he slipped the door guy a twenty-dollar bill and they chatted about nothing for a few minutes. New York City loved John Belushi because of things like that. That’s just who he was.

The doorman led us inside, and I remember it being a real solemn place, with some kind of heaviness in the air that I couldn’t put my finger on. It wasn’t quite my scene and I wasn’t totally comfortable with it. In keeping with the custom, we stashed our clothes in lockers and put on robes, then walked down a long flight of stairs to a huge, subterranean area that must have been the size of four basketball courts. It was dark and dingy down there and we went into a giant steam room that was encased in glass. There were old immigrants who were talking quietly among themselves, in near whispers, like they were conspiring or something. We lay down on massage tables and then guys started rubbing eucalyptus boughs on our backs. It just didn’t feel right to me, so I got up to leave: “I’m out of here, John. It’s just not my thing.” But Belushi wasn’t going to let me off that easy: “Relax, Bill. Lay down. Trust me.”

I was so exhausted that I didn’t have the energy to resist. I turned back and ended up falling asleep during a really fantastic massage. I woke up feeling great. We put our robes back on, went upstairs, and got down on the cots, where they brought us ice-cold shots of vodka. Very Russian.

During all of this, some men came in that looked like heavies. Gangsters of old New York. Their eyes were cold and tough—you immediately knew not to fuck with them—and they all wore really expensive, Italian suits. When they went to hang their jackets, you could hear the audible clunk of a heavy object slam against the side of the lockers. They were packing heat. Belushi just glanced at me and said quietly, “You didn’t hear that. Don’t look up at them. Don’t make eye contact.” We were surrounded by mobsters.

I went back to the hotel and took a nap and somehow made it to soundcheck on time. Belushi was already there at the venue. “I feel great!” he said. “Don’t you?” I did, actually. It was almost showtime.

Belushi loved music and he loved the Grateful Dead. His comedic partner, Dan Aykroyd, turned him on to the blues and he dove into it and became a scholar of the genre. He had a great singing voice and the same knack for perfect phrasing and delivery that he had with comedy. So he and Aykroyd put together a band, which they jokingly named the Blues Brothers. Originally the group was assembled just for a comedy sketch on SNL, but they knew they were onto something bigger. The band became real and they cut an album and then made a movie and went on tour. Belushi and Aykroyd created characters for the band—Jake E. Blues and Elwood J. Blues, respectively—but they took the music seriously. They recruited a fantastic lineup of players for it, too. Members of Booker T. and the M.G.s and backing musicians for Isaac Hayes and Howlin’ Wolf were in the band, along with a bunch of monster musicians from the SNL Band. Among other things, the Blues Brothers opened for the Grateful Dead on New Year’s Eve at the Winterland in 1978.

Well, two years later, backstage at the Capitol Theater after our bath house escapade, Belushi got it into his head that he wanted to sing backup on “U.S. Blues” with us that night. I thought it would be really cool to get Belushi out there with us, of course, so I went and told the band, but Phil was opposed to the idea. He vetoed it. I had to go back to my friend and tell him, “Sorry, buddy, but Phil said no.” There were no hard feelings or anything like that; it was what it was.

Why did Phil say no? I can’t say for sure, but I know he didn’t like my friendship with Belushi. He didn’t approve of it. I have no idea why—the two of us just had a grand old time together. But I didn’t want to rock the boat, so I respected my bandmate’s decision.

I had a really good show that night, and the entire band played well. We encored with “U.S. Blues” as planned and, right before the chorus, Belushi took everyone by surprise by cartwheeling onto the stage. It was a comedic ambush. He had on a sport coat with small American flags stuffed into both of his breast pockets and he landed his last cartwheel just in time to grab a microphone and join in on the chorus. The audience and everyone in the band—except for Phil—ate it up. It couldn’t have been rehearsed better. Belushi had impeccable comedic timing, musicality, balls, the works. And, apparently, he didn’t take no for an answer.

I really loved my friendship with Belushi and it was especially cool for me because I was such a fan of his work, long before I ever met him. In fact, right before we began rehearsals for our first Saturday Night Live appearance, I got his phone number from the producer, Lorne Michaels, and called him up just to tell him how much of a fan I was. I’ve never done anything like that before, but I couldn’t help myself.

After that first SNL performance—November 11, 1978—the band joined the cast for a wrap-up party at the Holland Tunnel Blues Bar. It was really just a party space that Belushi and Aykroyd rented, which may or may not have been officially licensed. They put in a jukebox and filled it with blues classics, and they brought in a primitive PA system and some house instruments, to encourage impromptu jams after SNL tapings—or any other time that was clever. The bar itself was largely unfinished and certainly unrefined. Belushi kept summoning me down to a shady spot in the basement to snort coke and rave about whatever. We had an audience of rats down there; we didn’t care. It was a real fun, loose time.

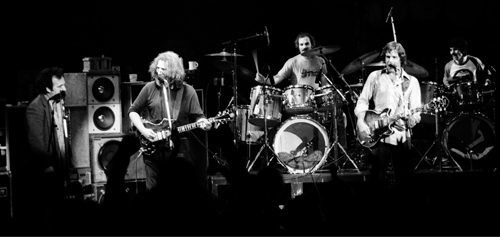

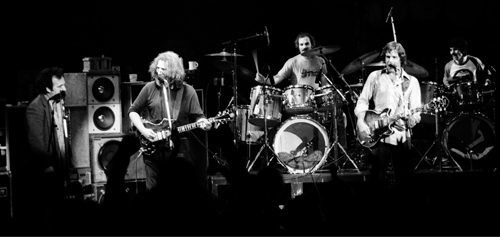

![]() The night that John Belushi crashed the stage. March 30, 1980. (Jay Blakesberg)

The night that John Belushi crashed the stage. March 30, 1980. (Jay Blakesberg)

One of Belushi’s famous impersonations was of Joe Cocker. We played with Cocker at Woodstock and also shared a bill with him a month prior to that at Flushing Meadows Park in New York—the site of two World’s Fairs. Anybody who has seen the Woodstock movie, where Cocker performs “With a Little Help from my Friends,” knows that he gets a little crazy with gesticulations and facial expressions when he sings. He really feels it and he used to be able to let go and flail about without any self-consciousness. It was admirable, on a level. But then Belushi imitated him on SNL and suddenly Cocker got pretty embarrassed by the whole thing and he took offense and it changed the way he performed—he toned everything down. He became more self-aware.

One night in 1976, Cocker was the musical guest on SNL. Belushi came out onstage during his rendition of “Feeling Alright.” The two were dressed exactly alike and Belushi duplicated every movement, every expression, even the vocals. He nailed it. He didn’t exaggerate because he didn’t need to; Cocker’s stage presence was ripe for parody. Belushi didn’t mean any harm by it, of course, and even though Cocker was mortified at first—if you watch the footage, you can see he’s a bit thrown off—he was a good sport about it, in the end. At the time, though, I don’t think he was too thrilled.

Well, when Belushi and I were hanging out in my hotel room one night, I asked him to do his Cocker impersonation. He left the room and when he came back in, just seconds later, I swear Joe Cocker himself entered the room. Belushi was even funnier in real life than on the screen. If that’s possible.

Weir and I hung out with him a couple weeks before he died. On February 21, 1982, we were playing at UCLA’s Pauley Pavilion—the same building where Bill Walton rose to fame as a college basketball player—and I was struggling just to stay awake because, once again, I hadn’t slept the night before. One of our roadies said, “Billy, look behind you,” and lo and behold, there was Belushi, making all kinds of funny faces at me. I cracked up and my energy returned and we partied with him after the show.

He died just twelve days later. Of an overdose. A speedball, which is a dangerous combination of coke and heroin, is what did it. I sort of want to say that L.A. killed him, but it could’ve happened anywhere. He moved to L.A. for film work, but they didn’t love him there as much as they did in New York.

Hearing the news of his death almost killed me, too. I’m not making a metaphor here. I was living in Novato with Shelley and I was driving home, listening to a Bay Area radio station, when they interrupted the broadcast: “John Belushi was found dead…” My heart nearly stopped and I almost got into a horrible car wreck. He was one of those irreplaceable ones. Time has proven that to be true.

If there’s one thing I learned from Belushi, it’s that humor saves the fucking day. True humor only knows and adheres to itself. It’s not about putting someone down or making fun of race or gender. Watching Belushi perform was like going to a little Burning Man of the mind; it was wild, free, full of abandon, reckless, daring, artistic and it spun reality into all sorts of twisted and contorted dimensions. He didn’t tell jokes with punch lines; he was both the joke and the punch line. He was an artist and his canvas was humor. And humor saves the day, every time.