Much has been made about the Grateful Dead house at 710 Ashbury Street in San Francisco but we’re not really going to make much of it here. For one thing, I only really lived there for but a moment. A couple of weeks, at most. We can talk about it, but it didn’t have the same magnitude, in my mind, as Olompali or Lagunitas or even the Pink House.

Our place on Ashbury Street was the same boarding house where Scully and Rifkin first set up the band’s office, while managing both the band and the house. It was no coincidence that when we needed to leave Camp Lagunitas for the real world, rooms there mysteriously began to open up until we took over the entire building. “We knew the management.” And that’s how 710 Ashbury became the Grateful Dead house.

There was another Victorian across the street, at 715 Ashbury that, while not nearly as famous, is still a part of the story. Sue Swanson and Ron Rakow, both eventual Grateful Dead employees, lived there. So did Alton Kelley and Stanley Mouse, the famous psychedelic poster artists who did several of our album covers and whose art remains a big part of our identity today—most notably the “Skull and Roses” image. Also of note: 715 became somewhat of a nest for Hells Angels. So you had the Grateful Dead on the one side of that street, and the Hells Angels on the other. Kinda a nice juxtaposition—and the names play off each other, too.

Like many San Franciscan streets, Ashbury is on a hill. I heard that Ken Kesey was driving down it one day and his brakes gave out and he had to make a quick decision: he could crash into the Grateful Dead house, or he could crash into the Hells Angels house. He chose the Hells Angels. Wise choice from our perspective but perhaps questionable from any other.

The Grateful Dead posed for band pictures on the front stoop of the 710 house and one of those images is now rather iconic. A thin, beardless Jerry is grinning from the doorway, Pigpen’s holding a rifle with a real outlaw aura to him, Bobby—by contrast—is playing the innocent; Scully and Rifkin are on the stoop, smiling; Phil is looking at me; and I’ve got my arm raised, finger pointed upward, as if in some kind of peaceful warrior battle cry. Photographed by Baron Wolman for Rolling Stone, over the decades it has become one of the band’s most enduring images. Maybe that’s why so many people, both Deadheads and otherwise, get their picture taken in front of that front gate whenever they visit San Francisco.

It helps that the house was just a few short blocks up from the intersection of Haight-Ashbury. When we weren’t hanging out at the house, we’d walk down Ashbury, hang a left on Haight, and hang right there with the throngs of like-minded people gathered outside, on the street. That stretch became hippie central, a phenomenon, a time and place that has since made it into the history books. We really became entrenched in that scene, if not synonymous with it. Wandering around Haight, you’d end up bumping into everyone you wanted to find and—as the song goes—strangers would stop strangers, just to shake their hand. It was also a brisk walk to Golden Gate Park and its eastward extension, the Panhandle. Both of these public spaces would be “instrumental,” so to speak, during our time there.

For the most part, during the band’s tenure at 710 Ashbury, it wasn’t where I spent the night, but it is where I spent most of my time. There’s that story of Weir getting in trouble with the police for throwing water balloons off of the roof—that’s been written about in every book (including this one, now). Stuff like that is probably the real reason that house became so famous. As at all of our group residences, outrageous shit happened at least once every time the hour hand circled back around. Sometimes, the minute hand, too. To this day, tourist buses still go down Ashbury Street to view the famous “Grateful Dead house”—minus the water balloons—and it’s a permanent part of San Francisco’s “map of the stars.” It’s become that kind of thing.

But living there wasn’t exactly glamorous. There were too many people for too small a space, no privacy, and the whole building just became this electric zoo with an open-door policy for just about anyone. Phil and Florence wanted out of there. I wanted the same thing. And, back then, I also just wanted to follow Phil, as a person, in the same way that I wanted to follow Jerry, as a musician. Phil was like an older brother to me in those days. That’s an important point to remember.

The two of us relocated to a house in a neighborhood called Diamond Heights, about two miles uphill from Haight-Ashbury. Phil brought Florence with him, and I still had Brenda and our daughter with me, at that time. So Diamond Heights had something of a family vibe going for it. When we wanted to run away and join the circus, which was on a daily basis, we’d head on down to 710 and take it from there.

I wasn’t at Diamond Heights but for a minute before I broke up with Brenda and had our unlawful marriage lawfully annulled. I basically just woke up one day and told her that she got her wish. It was over. Time for her to leave.

The earth was spinning on its axis at a dizzying pace, and it’s not that the world revolved around me, it’s just that I was in orbit too, moving from place to place, keeping up with changes within me, changes within my country … and changes with my love life. It seemed like no time really passed between saying good-bye to Brenda and saying hello to a girl named Susila Ziegler.

I met Susila at 710 Ashbury although she lived at her parents’ house in Mill Valley, which is an affluent town directly across the Golden Gate Bridge, just minutes north of the city. We started hanging out, then we started going out, then we became a couple.

Susila was a very beautiful young woman, an artist, and in fact, she designed one of the first Grateful Dead T-shirts and began selling them at shows. That might not seem like a big deal now, but Susila was actually one of the first people to ever do this for any rock band. Remember: the concert business was just starting back then, just figuring itself out, and San Francisco led the way. Silk-screened T-shirts were fairly new, in and of themselves. Susila made and sold Grateful Dead shirts and then she made shirts for the Allman Brothers and suddenly T-shirt sales—and, later, other merchandise items—at live concerts became a key component of every band’s income. Eventually, the Grateful Dead’s merchandise arm would grow into a business unto itself, with everything from pint glasses to dog collars sporting the band’s name, logo, or artwork. Anyway, Susila did well with that and sometimes I would even carry boxes of her T-shirts to the shows to make sure they got there. We were partners; we had a good time together.

I remember my first date with Susila. We drove from San Francisco up to Healdsburg, a charming little wine town in Sonoma, one county north of Marin. Northern California. She had a friend who had a farm up there. We got into a one-man sleeping bag and made love that first night and I knew that we were probably going to see each other a lot after that. It was freezing, so we had to stay really close to stay warm, and that was kind of romantic. Very romantic, in fact. Driving up to Northern California seemed like a big deal to me at the time. It was a great adventure and the start of a great romance and I ended up marrying Susila and having my son, Justin, with her. Justin was born on June 10, 1969, just in time to attend Woodstock. But we’re still in 1966, having high times on Haight Street.

We were finally playing a lot of shows and attracting an audience. Not Acid Tests—actual shows. We’d practice at the Heliport in Sausalito during the day, and play out in San Francisco at night. We still played some tiny rooms, like the Matrix, which is down in the Marina District and is now some kind of ultra-lounge. But we were moving up in the scene. And fast. We were doing multiple-night runs at the Fillmore, which were promoted by a guy named Bill Graham. And we even played at his bigger room, Winterland, which was a repurposed ice skating rink that could hold more than 5,400 people. It’s the same place where the Band filmed The Last Waltz, ten years after this. We also played a number of two-night stands at the Avalon Ballroom, a psychedelic dancehall run by Graham’s competitor, Chet Helms, and his company, the Family Dog. Of course, all of these venues are now legendary (even though only the Fillmore survives). San Francisco became the cradle for the live music concert industry and these venues were its playpen.

When we didn’t have a gig, we’d create one. We played for free, just for the fuck of it. At the time, it was making a virtue out of necessity: we just loved playing together as much as we could. It wasn’t a business; it was an adventure. With Scully and Rifkin as our managers, we were able to make money without having to hold outside jobs. We could just play music—which is all we ever wanted to do. And we wanted to do it all the time. We were a working band. We played a lot of gigs around the Bay Area and those shows covered the cost of living for all of us. They also gave us the resources to put on free concerts whenever we weren’t playing a ticketed show.

When we played for free, everything came together with a certain grace that seemed almost like divine intention. But it can take a lot of people to line the pieces up in order for them to fall into place. It takes a community to make a community. The Panhandle concerts were an example of this poetry in motion. In order to use electric instruments and a PA system, we needed power; there were no plugs in the park, obviously. So we ran extension cords from a friend’s apartment, stringing them on streetlights over Oak Street and snaking them into the Panhandle.

On New Year’s Day, 1967, we played a free show that the Hells Angels threw together for the Diggers, a radical group of hippies who thought that everything should be free, not just music. An appealing concept, but not really a sustainable one, with a message that resonates less and less as you get older. I wonder, do the Diggers still believe in the Diggers? Can they still dig it? That said, we played for free for them that day, along with Big Brother and the Holding Company, right there in the Panhandle. We were all so happy; it was just a beautiful happening.

A few months before that, on October 6, 1966, we performed in the Panhandle as part of the Love Pageant Rally, for rather unfortunate circumstances—it was to mourn the end of legal LSD in California. The rest of the country would soon follow suit. When acid became illegal, the hippies became criminals. Nonviolent, otherwise law-abiding, criminals. All because we liked to expand our consciousness. Much like a jazz funeral or a celebration of life, we decided to be festive about it and, after parading down Haight Street, we played for free in the park—again, with Big Brother and the Holding Company.

We also played a number of free shows in Golden Gate Park during this era, and one of them in particular stands out, because some have said it represented the peak of the whole Haight-Ashbury scene and the San Francisco hippie movement—the Human Be-In on January 14, 1967. More than 20,000 people filled the Polo Fields in the park that day. Most people walked—band included—right from Haight Street, through the park and to the field, without any agenda. It wasn’t a rally and it wasn’t a festival. It was simply a BE-IN. Be here or be square. Be a human be-ing. Bear handed out doses. Allen Ginsberg and Timothy Leary spoke. In addition to the Grateful Dead, all the other usual suspects were there, too, including Quicksilver Messenger Service and Jefferson Airplane. I remember playing it, but I don’t remember much more about that day.

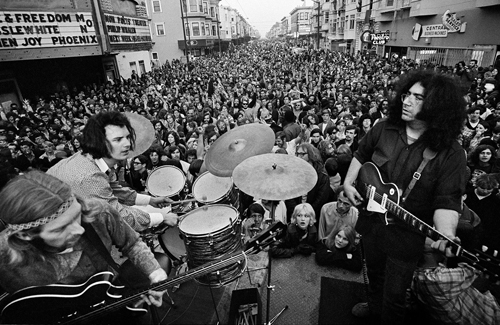

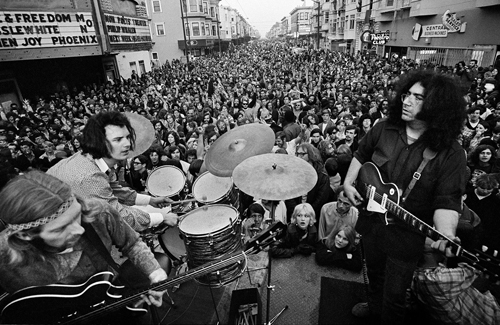

A year later, on March 3, 1968, we staged a coup on Haight Street and played on the back of two back-to-back flatbed trucks. Instead of concrete and cars, Haight Street became a sea of people. You couldn’t see the street for the crowd. The previous month, there was some kind of incident involving police and hippies, and a near riot ensued. The city offered to close the street to traffic on March 3, for festivities, as some kind of peace offering. The Grateful Dead decided to take advantage of the situation and we suddenly stormed the street with a surprise show. There’s a famous photograph from that one that remains one of my favorites. Of course, there were lots of other free concerts as well, each one special for one reason or another.

![]() Dancing in the streets: Haight Street. March 3, 1968. (Jim Marshall)

Dancing in the streets: Haight Street. March 3, 1968. (Jim Marshall)

The concept of a free rock show has changed over the years, so let me make this clear: when we played for free, there were no sponsorships. No hidden deals. No kickbacks—just kicks. We played because we wanted to play. Sometimes those gigs were conceived of mere hours before we started playing, because one of us said that they felt like it. In hindsight, it was probably genius marketing, because massive crowds gathered once word spread, and every one of those shows expanded our audience. I guarantee it.

The more traditional way to gain an audience and become successful is to record records, release them, promote them, and go through the machinery of the music industry. Nowadays that’s not quite as important and you can circumvent the system entirely and still have a respectable career. But back then, if you wanted to make it as a band, you had to first get a record deal. So, around the time we relocated to San Francisco from Lagunitas, we signed to a major label. Warner Bros. Records. We got a significant advance, given the standards for the time. Something like $10,000. We were on our way. We were only a little over a year old, as a band. We had a contract worked up by September and completed the deal later that fall.

In January 1967, we went back down to L.A., this time with the backing of a record label, and set to work recording our first album—San Francisco’s The Grateful Dead. We were in Studio A at RCA Studios. We also were on a lot of Ritalin. The album sounds like it. We played everything too fast. We were nervous.

Phil was into speed—many years ago, not now of course—and he had a stash of Ritalin. He used to drive a mail truck on Market Street in San Francisco during rush hour and he became The Crazy Postman. He’d go out there and just beat everybody to the line and race like crazy. I can see speed working for something like that. But it didn’t work for recording music. At least, not for our music.

Playing music on speed sounds like you’re playing music on speed. It was our first experience with recording for the big league, and we all wanted the album to be popular. We wanted it to work. We even had a big-shot producer—Dave Hassinger, who came to us straight from mixing the Rolling Stones. Hassinger told us the record was great. It wasn’t.

Some of the songs, like, “Morning Dew” and “Cold, Rain and Snow,” became concert staples, for years and decades to follow. They were covers that we enjoyed playing, but their recorded versions failed to capture the energy that we had when we performed them live.

I felt like, “Okay, we’ve paid our dues. It’s our time. The record is going to be a hit.” But our time wasn’t going to come for a while and neither would our first hit record. It wasn’t going to be that easy. We weren’t that good yet. We were still learning how to be a band. We were also still just learning how to live.

After living at Diamond Heights for a while, Phil and I migrated to a two-story Victorian on Belvedere Street, a hop, skip, and a couple jumps away from 710 Ashbury. I now had Susila with me. Phil was still with Florence. The guy who hosted that San Jose Acid Test lived down the block from us and we smoked a lot of hash at his place. Pigpen and his girlfriend moved onto that block too, at some point. For some reason, I remember that we had extremely strong coffee every morning. Little details.

But before that happened, in May 1967, the Grateful Dead took another extended band trip that brought back the spirit of Olompali and Camp Lagunitas. My friend from boarding school, John Warnecke, invited us up to his family’s encampment on the Russian River. We ended up setting up camp there for a little bit—a couple weeks or so. It was a really far-out place for us. Warnecke’s dad was a famous architect—John Warnecke Sr. He’s probably most known for designing John F. Kennedy’s tomb at Arlington National Cemetery but he also designed Hawaii’s state capital building. He built a beautiful vacation house for his family, with all these cabins around it—wood platforms with canvas tents on them and beds inside—on the Russian River, a couple miles shy of Healdsburg. We stayed in the cabins and it was a perfect situation for us. One of the wood platforms, originally intended for a campsite, was right next to the river. We set up all the equipment on that platform and played out there. Naturally, we took a lot of acid and had some really outrageous times. I don’t remember drinking that much there, but I do remember taking a lot of acid.

The Russian River area of Sonoma County is a popular vacation spot and road trip destination for city dwellers from the Bay Area. They drive up on Highway 101 and camp out for weekend getaways and stuff like that. It’s also the home of the infamous Bohemian Grove. But we had our own little bohemian groove going on. We set up our speakers facing the river and we’d wait until people kayaking downstream would get right in front of them and then really let them have it with all kinds of birdcalls and frog sounds, really weird vocal jams and stuff, all turned up to 110 db and amplified through speakers. I don’t know if any kayaker actually fell over from the shock of what sounded like a giant eighty-foot bullfrog or anything, but we sure tried.

Perhaps the most significant thing to happen during our Russian River trip was that Jerry remembered some words his friend Robert Hunter had sent him. He used them for a lyric in a new song that we worked up called “Alligator”—and that was the start of Garcia and Hunter’s incredible songwriting partnership.

I think Jerry came up with an initial sketch for “Dark Star” while we were on that river trip, and Weir and I also came up with an idea that would eventually form the basis of “The Other One.”

The Russian River was also just a really great place to practice and experiment, because it was outdoors, during that graceful transitional time when spring turns into summer. It’s in the middle of wine country so there are beautiful vineyards everywhere. And that time of year, it never gets too hot during daytime, nor too cold at nighttime.

We played a lot of music there and became a better band. Pigpen was still our leader and he wrote a bunch of tunes during the stay. The band always liked being in the country and, in those days, we also liked living together. The closer the better. We only had one car, really—mine—so that mandated being close. That was a good thing. Those were good days and Russian River was a good trip.

Not long after that, we got to do what every rock band in the world dreams about—we played New York City. The holy grail of venues, Madison Square Garden, was still a dozen years away, for us. Eventually, we played the Garden a total of fifty-two times, and, for the longest time, we even held the records for the most shows and sell-outs until Billy Joel beat us … decades later.

But our first gigs in New York were far different experiences from headlining the big top. We had to outrun a gang one night, on our way back to the hotel, and Weir almost got mugged another night. It was a tough city back then. Still is, but not in the same way that it used to be. The reason I’m bringing this up is because it’s so different from anything we had been exposed to, growing up in Palo Alto or even living in San Francisco.

New York was like a pickpocketing dragon, capable of burning you and swallowing you whole—but it also was a really exciting place to come and play music. We were so excited that it was hard to sleep at night. The rock scene was just getting started and the clubs were just starting to put on rock shows. The Rolling Stones had been around, the Beatles had been around, and when Jimi Hendrix hit that scene, that was it—it was all Hendrix then. The Grateful Dead were unheard of.

We played free shows in Tompkins Square Park and in Central Park, to a very different audience from the kind we were used to in San Francisco. We established a residency in an area called Greenwich Village. That neighborhood served as the birthplace for the Beat Generation, which was interesting to us because the beats’ other geographical focal point became a neighborhood called North Beach—in San Francisco.

Back home, we had been hanging out with our champion—and Beat Generation hero—Neal Cassady. But, a decade earlier, he was in the Village, hanging out with Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg and all the famous beats. Most of which also made their way to San Francisco. The two cities had some kind of underground connection, even though—on the surface—they were worlds apart.

By the time we got there, Greenwich Village was also home to the East Coast folk scene, with Bob Dylan leading the charge. It was pretty neat to be in the epicenter of this movement that was distinctly different, yet directly and spiritually related to the one we were a part of, nearly 3,000 miles away.

We set up shop at the Café Au Go Go, a small club on Bleecker Street, reminiscent of the Matrix in San Francisco. Lenny Bruce, the comedian, made that place notorious a few years earlier when he was arrested on obscenity charges for a pair of shows there. Back then, the First Amendment didn’t always apply—you couldn’t swear onstage. There were certain things you just couldn’t say. But you could jam, so that’s what we did. (Before we were in a band together, Garcia actualy took a job transcribing recordings of Lenny Bruce’s routines at the Café Au Go Go for use in Lenny’s obscenity trials.)

There was a theater right above the café and Frank Zappa happened to be playing there. I went and watched him throw tomatoes at the audience. I picked up that he was brilliant, but it didn’t get me off to see food being used as a gimmick during a rock concert. It was like Gallagher smashing a watermelon and calling it comedy. A backstage food fight is sometimes a necessity, but Zappa’s food theatrics just distracted me from his music. And that’s why I was there—for music. I wasn’t yet hip to the idea of having fire dancers onstage or anything like that, but I would warm up to it in time. I loved being in New York City and I still do, to this day.

A few weeks later we were back west, headed to the Monterey Pop Festival on California’s Central Coast, just above Big Sur. The festival took place at the town’s fairgrounds from June 16 to 18, 1967 and the lineup featured Simon & Garfunkle, Otis Redding, Eric Burden and the Animals, the Mamas and the Papas, and a bunch of Bay Area bands—including three we were rather accustomed to playing with: Quicksilver Messenger Service, Jefferson Airplane, and Big Brother and the Holding Company. As Big Brother’s front woman, Janis Joplin’s performance at Monterey was a career-maker. Especially since, unlike the Dead, they allowed their set to be filmed. You’ve probably seen the footage.

Monterey wasn’t a career-maker for us, though, but—we were kind of fucked from the start on that one. Here we were, this young band—“the Grateful what?”—and we were sandwiched right in between The Who and Jimi Hendrix. I was intimidated. We didn’t really have our own thing yet and we had to follow The Who. They were a great English rock band that was already established back in their homeland, and they really knew how to put on a spectacle; they wore all these beautiful show costumes and delivered power-chord anthems with visual flair. Then, after us, came the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Hendrix was at the top of his game and to top it all off, at the end of the set, he even set his guitar on fire. And we had to play in between these two giants?

It was a very scary gig for me, because of that. I remember throwing up before we went on. I was so frightened, so nervous, that my left hand locked up while we were playing. I was terrified of being onstage at such an overwhelming event. In time, I would get used to playing shows like that, but it took awhile to really get comfortable. By any standards, it’s pretty unusual to be squashed between The Who and Jimi Hendrix. I went back and listened to our set sometime later and it was actually quite reasonable—it wasn’t all that bad.

Monterey was the first big gig we played with real stars walking around backstage. David Crosby was there with the Byrds, and he sat in with Buffalo Springfield, a new sensation that featured his future bandmates Neil Young and Stephen Stills. (For Buffalo Springfield’s set at Monterey, David Crosby was a substitute for Neil Young, who had taken a temporary leave.) We had seen a Buffalo Springfield gig on the Sunset Strip in L.A., back when we were living at the Pink House—but at the Monterey fairgrounds, we were on the same playing field.

We became friends with all of those guys that weekend. Crosby was wearing the classic, hippie, high-roller leather coat with fringes and the whole nine yards. But he was such a kind person and he taught our guys some tricks to help them sing harmony parts. A few years later, he gave us hands-on instruction when we were recording American Beauty. Thanks, David.

The Who were another band at Monterey that were social and engaging that weekend, and they all came by my hotel room the night we both played. They stopped in for a little while just to say hello. It was Keith Moon’s time—the wildest drummer they ever had. He passed away in 1978, darn it, and The Who were never quite the same without him. He could’ve been a great actor, too, because he was Mr. Personality. I remember watching him tear up his drum set and throw it all over the place, and seeing Pete Townshend smash his guitar all to hell at the end of some song. It was as over the top as Hendrix setting his guitar on fire. It really surprised me when, back at the hotel, there was a knock on my door and the Who were all just standing there, like, “What are you doing? Want to hang out?”

The Who teamed up with the Grateful Dead for a pair of stadium shows a decade later, and Townshend sat in with us in Germany once, but I didn’t become friends with him until 1993, when he did a theatrical version of The Who’s Tommy on Broadway. I got to see the dress rehearsal for that, because the Dead were in town for a multiple-night run at Nassau Coliseum on Long Island. Townshend and his son became friends with my son, Justin, and they’ve worked together on some video projects. They keep in touch and all of that.

Although I never had the opportunity to become close with Keith Moon, it was an honor to have met him and an even bigger honor to have shared concert stages with him, over the years. He was one hell of a drummer. As it turns out, a few months after Monterey, I ended up meeting another drummer that wasn’t too bad, either. Meeting him would forever change the identity of the Grateful Dead and, in turn, my life.