The first time I met Mickey Hart was at the Fillmore Auditorium in August of 1967. The original Fillmore, which is still going strong at the corner of Fillmore Street and Geary Boulevard, is in an old jazz district of San Francisco that was once nicknamed “Harlem of the West,” back when jazz and blues nightclubs lined the strip.

The Grateful Dead had performed at that historically significant venue many times before I had been introduced to Mickey, enough that it was almost like our second home. In fact, we were the house band. We played that room no less than thirty times in 1966 alone. Our first Fillmore show was on December 10, 1965, about a week after we had changed our name from the Warlocks. We returned to the Fillmore on January, 8, 1966, for an Acid Test.

When we came back there a week or so after that, for a Mime Troupe Benefit, the promoter, Bill Graham, thought our name change was bad for business. He was thinking only about that night; we were thinking about the rest of our career. Finally, we came to a compromise—the first of many with that guy—and he listed us on the bill as “The Grateful Dead: Formerly the Warlocks.” Which was—and is—true.

Graham is perhaps the most famous live music promoter of all time and, even though we lost him in 1991, his legend lives on. Deservedly. He was a true trailblazer. Many of his innovations have become, and remain, standard practice.

But one thing that was uniquely Graham’s, and which has largely disappeared following his death, was the creative way in which he’d string a lineup together for a show. He wanted to educate his audience and he saw it as a service to music fans—he’d take the hip new thing and put them on a ticket with overlooked royalty, introducing young crowds to the masters. He’d bill upstarts next to immortals. Sometimes (like, say, March 17, 1967) the kids came for the upstarts (like, say, my band), but then had their skulls cracked open by the legends (like, say, Chuck Berry). And other times, Graham would give a brand-new band their first big break by putting them on as an opener for a local favorite, essentially handing them hundreds of new fans in a single night. Regardless of genre or age or anything like that, if you were an incredible artist, Graham would book you at the Fillmore. And he wouldn’t book you there otherwise. So, as fans, we’d just go and listen and discover. It was our music school.

The headliner the night I met Mickey Hart was Count Basie. The Count Basie. His drummer was Sonny Payne and watching him play was fascinating and inspiring. You could barely hear Count Basie count the band in, but then all of the sudden, out of the clear blue, Sonny would stomp on his bass drum. The volume alone would startle you. And that was without a bass drum microphone. I was blown away.

I was staring at Sonny in total awe when I felt someone tap me on my shoulder. It was Mickey Hart. I had never seen him before, but he introduced himself as a fellow drummer and friend of Sonny’s. We started talking all about rhythms, anything and everything to do with drumming, and he told me about stuff he could do that I wanted to learn. That was convenient, because he was a drum teacher. Matter of fact, the year before we first met, Mickey beat his dad in a drum championship. His dad was defending his title from the year before and lost to Mickey. They were in some kind of lifelong competition with each other and the ramifications of that would end up having significant consequences for the Dead down the line. Both of Mickey’s parents were award-winning drummers. But that night, we weren’t thinking or talking about family matters. We were thinking and talking only about drums.

And everything Mickey told me that night turned out to be true: he was a great rudimentary drummer. He had one of his drum students with him at the Fillmore, a guy named Michael Hinton, who went on to become the premiere drummer for the Broadway production of Les Miserables. I got to see him perform it with the original cast and it was amazing. Hinton also drummed for Jefferson Airplane at one point, among many other accomplishments, some of which have certainly overlapped with the Dead’s universe over the years. (On the other end of the spectrum, I heard he spent years touring with Liza Minnelli. Solid work. Steady work. Hey, whatever works.)

After Count Basie’s set, Mickey and Hinton cajoled me to come out to their car and they both took out their sticks and started doing tricks that I didn’t know how to do. I mean, I knew how to play drums and all, but I sure didn’t know how to do this stuff. I knew immediately that it would be beneficial for me to learn these things. Later that night, I took them to the Matrix to check out Big Brother, with Janis Joplin in fine form. The whole scene was a new discovery for Mickey, a Brooklyn street kid that had just recently wrapped up a stint in the air force. My new discovery that night was Mickey himself, and the idea that this guy could actually make me a better drummer. And that was my mission.

I had developed an off-the-wall style that worked for me, and it seemed to work for the band, but I didn’t want to just be something that worked. I was reaching for mountaintops that were a hell of lot higher than that, and in order to reach that altitude, I needed to pack a few more tools in my rucksack. I realized this that night.

I needed to uncover what rudiments meant to drumming and I wanted to attain the freedom that they had to offer. The way rudiments are set up, you can play two beats with one hand, which gives you time to move your other hand to a different place. That way, you can alternate naturally by going side to side without missing a beat. Mickey was all about teaching this and he taught it to me. He also had me play marches and I got pretty good at them—well, actually, I wasn’t great at them. But I got so that I could play them. I didn’t like them any more than I did when I was a kid, though.

Under Mickey’s guidance, I practiced the fundamentals until they became embedded in my foundation and then I used the rudiments as if they were bricks that I then cemented together, forming a bridge between the drummer that I had been and the drummer that I wanted to be. And then I crossed it.

I’m going to get technical for a moment, so bear with me: a single paradiddle is four beats; a double paradiddle has two more beats than a single paradiddle (six beats). A triple paradiddle has two more beats than a double (eight beats). It may sound simple but it’s tricky.

Mickey made up this great rudiment called a false-sticking double paradiddle. It has the same number of beats as a regular double paradiddle (six), but you accent the first beat on the same hand every time, instead of alternating. The divisions are split up differently, but with the same number of beats, so it sounds the same. His false-sticking trick works out particularly well when you’re playing in 3/4 or when you want to accent three against four. Learning these techniques from Mickey proved instructional; watching him play around with them was inspirational. The end result is that I became a better player.

Somehow the idea of having Mickey sit in with the band came up, so I invited him to come practice with us over at the Heliport in Sausalito. The story goes that he tried to make it out there, but he got lost and couldn’t find the place. Maybe that’s true or maybe it was just an excuse for not showing up. The statute of limitations has worn off by now, Mickey. We wouldn’t be mad at you …

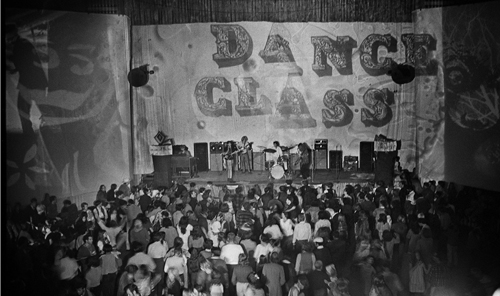

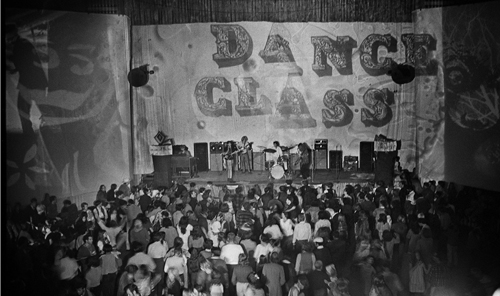

Regardless, I still wanted him to sit in with us, so I invited him to come down to the Straight Theater, where we had scheduled an interesting run of shows on September 29 and 30, 1967. The theater was on Haight Street, at the intersection of Cole, just a few blocks away from 710 Ashbury, and our friends were running things. But this was during that challenging time in history where dancing at a rock concert was like ordering booze at a bar during Prohibition. It felt right, but it was banned by law, unless you had a dance permit. San Francisco was certainly not going to issue the Straight Theater a dance permit for a pair of shows by the Grateful Dead. However, we found a delightful little loophole and the defiant act of exploiting it made the shows especially satisfying for us—you needed permits for a dance concert, but not for a dance school. Class was about to be in session. We charged a “registration fee” instead of selling tickets and everyone got membership cards on the way in. The cops were there but couldn’t do a damn thing. The media loved it. And we taught some people how to dance, all right.

Mickey came down on the second night and, during set break, we rounded up a second drum kit. Even though Mickey didn’t know any of our songs, or the other guys in the band … or anything about us, really … I thought it would be a fun experiment to have him sit in with us. Nobody could’ve predicted that from that moment on, Mickey Hart would be a member of the Grateful Dead.

![]() Class was in session at the Straight Theater on Haight Street, September 29, 1967. The next night, Mickey Hart played with us for the first time. (Jim Marshall)

Class was in session at the Straight Theater on Haight Street, September 29, 1967. The next night, Mickey Hart played with us for the first time. (Jim Marshall)

But sure enough, that’s what happened. After the show, Jerry allegedly said something along the lines of, “This is the Grateful Dead!” and, just like that, Mickey was in the band. He even moved in with me, in a closet underneath the stairs at the Belvedere house—the same kind of “bedroom” that Harry Potter’s guardians gave him on Privet Drive. Like Potter, Mickey Hart seemed capable of magic. He later proved this to be true. (He used to drum at the very edge of it.)

As a side note of sorts, Weir also moved into Belvedere at some point. So, I suppose, with Phil and me (and our ladies) in the two respective bedrooms, Mickey under the stairs, and Weir sleeping God knows where—hence, four of the six active band members—it silently transformed into the “real” Grateful Dead house. 710 Ashbury was more for show; something to give the tourists.

But first, before Weir moved out of 710, there was the famous pot bust that happened that fall and which made headlines (including a piece in the very first issue of Rolling Stone on November 9, 1967, and a photo in the local paper showing an irreverent-looking Weir handcuffed to Florence on the front steps). I wasn’t a part of it and, luckily, I wasn’t even there that day. I probably had contraband in my possession at the time—but over at Belvedere. I was never even a suspect. They were busting the house more than the occupants. The cops just wanted an easy target to make some cheap headlines, just as public opinion was beginning to sour on the whole Haight-Ashbury scene. The one and only “Summer of Love” was officially over and the police department wanted everyone to know it. So they raided the house and they arrested whoever happened to be at the house that day, including the one guy in the band that didn’t use drugs—Pigpen.

Also: their search failed to turn up an entire kilo of high-grade pot, Acapulco Gold, sitting on the top shelf in the pantry, not even hidden, just waiting to be discovered … or smoked. Bobby and Pigpen ended up paying small fines, as did some of our management and crew. In the end, the publicity was probably good for us. After all, it got us into the pages of Rolling Stone. So we should probably thank both the snitch and the police department for the extra help.

Anyway, as I was saying, when I invited Mickey to sit in that night at the Straight, I didn’t think it would result in an invitation to join the band. I didn’t think we needed two drummers, but it was kind of nice having another drummer there to buddy up with and play off of—both literally and figuratively. We became a special unit within Team Dead. Partners, brothers … “Rhythm Devils.”

Instead of hazing Mickey, we had our own initiation rite—we fed him acid. That’s the day he became our brother and, after that, things immediately got even more interesting. We rented a new rehearsal space inside the SF city limits where we really gave birth to a new subgenre of rock ’n’ roll—one that, to this day, only the Grateful Dead could ever really play.

The rehearsal space was in an old synagogue, right next to the Fillmore, on the Geary side, where a post office now stands. Sometime after we left there, it was converted into some kind of a concert hall, known as Theater 1839 (for its street address on Geary). The Jerry Garcia Band played a few legendary shows there in 1977. After that, I think the name changed to Temple Beautiful and it began hosting punk rock shows for a while. When we used it, in the fall of ’67, Bill Graham may have actually owned the building. If so, that would explain why we rented it. Never mind the fact that it was right next door to the Fillmore.

In 1989, the building, as we knew it, burned down. Come to think of it, a lot of buildings that were connected to us through the years have burned down—the induction center in San Jose, the original estate at Olompali, a house in New Jersey that we stayed at for a bit, and so on. Weird. Also weird: right next door to the synagogue was a Masonic temple—the Alfred Pike Memorial Scottish Rites Temple—which became the headquarters for the Jim Jones’s Peoples Temple during the ’70s. Right before they departed for Guyana, never to return. That whole thing remains a genuine American tragedy and while the Grateful Dead had stopped practicing there a couple years before Jones and his people moved onto the block, it’s just one more crazy connection, for whatever it’s worth. You know, “There goes the neighborhood.”

Anyway, Neal Cassady would sometimes stop in at the synagogue when we were rehearsing and Mickey would get nervous about it, for some reason. Cassady would shake my hand in this way that really shook my entire arm, and he’d say, jokingly, “Are you loose, Bill? Are you loose?”

There was also a wonderful synchronicity to Cassady’s appearances there, because it was in that exact time and space where “The Other One” really came into focus, and the song is partially about him. With the eight limbs of two drummers behind it, we got into that groove, that 6/8 thing, and it became its own animal. Appropriately enough, given the subject matter, the song is really just an open invitation to bust loose and it’s one of those all-terrain vehicles that is designed to take you down different roads every time, seeing around corners as you go. That’s definitely all Cassady, and that song is definitely one of my favorites.

It wasn’t until Mickey joined the band that we started experimenting with time signatures. Before then, we mostly played in fours—4/4. Then, with two drum kits set up at the rehearsal space (and two drummers), we started doing these more advanced things. All this also coincided with Phil turning me on to John Coltrane and Elvin Jones. I remember when I listened to Elvin for the first time, I thought, “This is legal? You can do that?” That kind of thing inspired us to enjoy and honor freedom in a musical sense; we began to push the boundaries in any direction, at any given time, in any given time signature.

It was there, at the old synagogue, where we first started playing rhythmically without worrying about the “one.” The “one” is the first beat of any measure. Put simply: It’s the downbeat. The thing that goes “boom.” We experimented with it. “Don’t play it anywhere!” Then we tried floating it—putting it in different places or throwing it out until the jam either suggested or demanded that we land on it. We’d create a new “one.” I’d throw it down and the whole band would drop into it so fast, you’d think we planned it that way. But we didn’t. We weren’t reading sheet music; we were reading minds. “Floating the one” would allow jams to shape-shift at will.

Sometimes we had to alter the “one” rapidly because we’d jam and Jerry would take solos and we’d stretch everything out and play some weird stuff in there, and then, suddenly, Pigpen would come back in—but he’d be on the off-beat. To make it right again, you have to take half a beat off, immediately, and make it the on-beat instead. If you’re on the off-beat and you take off a half beat, it becomes the on-beat. If you take off another half beat, you’re back on the off-beat. And it just continues like that, forever. It’s a mathematical thing at the quarter note level. Anyway, we’d be doing some rave, like “Love Light” for instance—Pigpen used to do some of his funkiest raving on “Love Light”—but he’d come back in sometimes completely off beat. We’d have to just switch it around; nobody in the audience even suspected it. That was kind of good practice, doing that shit.

Mickey was a great lobbyist for the drums. He was just so passionate about anything to do with them. We built a couple of drum sets together, over the years. We were both playing sets that had double rack toms, and we decided to push it further by putting a third rack tom up there. Nobody ever did that. As soon as we tried it, though, we began to see them everywhere. Maybe it was just a sign of the times.

Mickey always chased perfection in whatever it was that he was after at that particular moment. He taught me that the act of drumming was as much about motion as it was about contact—a great drummer will use their whole body, not just their wrists. You can hear such a difference.

Working with Mickey continued to help me throughout the Grateful Dead’s career. With him in the band, I was always game to accompany him on just about any experimental journey. I even allowed him to hypnotize me once, and I think it worked. As far as I’m concerned, he still has me hypnotized today.

I always felt like we became this four-armed, four-legged beast, instead of two human drummers. Mickey had a zany kind of energy that was persistently infectious to me; it reminds me of the wide-eyed enthusiasm of a little kid, with all this energy just pouring out purely and without restriction and without agenda, and it’s really a beautiful thing. You add that to his perfectionist side and he ended up with some wonderful stuff.

I’ve recently listened back to some shows we played in the 1990s, particularly the “Drums” and “Space” from the Spring ’90 tour, and there are really a lot of remarkable moments. It sometimes makes me wonder how I can even think about playing in other bands now, after that. Listen to some of that shit. Everything changed when Jerry left, and we’ll get to that in due time, of course. But fuck, man—with Mickey there, we became really good.

He and I also became prankster partners, like the Blues Brothers of the drums. We were playing somewhere in L.A. once, I can’t even remember the gig, but afterward we had a really lame limo driver and he went missing for a moment too long, so we stole the limousine. Mickey put on the driver’s hat and just started driving. I was in the backseat, laughing my ass off. We drove all around and and started to get hungry, so we hightailed it to Canter’s Deli. We were just digging into our food, when the driver came up huffing and puffing. We handed him his keys back. “There you go, buddy. We’re all good, right?” The limo was parked and there was no damage or anything like that. So it was all good, after all. It was all just kicks.

Long before that limo incident though, the band temporarily moved back to L.A.—in November 1967—so we could work on our second album. We scheduled a couple of shows at the famed Shrine Auditorium (where we debuted “Dark Star” on December 13) and blocked out some time at American Studios in North Hollywood.

Once again, we all moved in together, this time at a house that belonged to our friend Peggy Hitchcock’s family. Her family also owned an expansive compound in Millbrook, New York, that became headquarters for Timothy Leary’s intellectual gang of acid dropouts—we visited them briefly, earlier that year, when we had a few days to kill at the end of a brief Canadian tour. But that stay turned into a string of mishaps that ended up in something less than a story. (And it left us feeling less than thrilled about Leary and his whole head trip.)

Hitchcock’s compound in L.A. was a stone’s throw from the famous Ennis House, which was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. A lot of flicks, including Blade Runner, were filmed on location there. It was a giant fortress with creepy, long slitted windows, perfect for horror films. We mistakenly thought that Bela Lugosi lived inside its veiled walls, but I think that was just an urban legend.

We moved in down the street and found ourselves right at the smog line, so there was often a red cloud, right at eye level from the house, which made it kind of weird. We played really hard in that house, though. I’d practice by myself, then I’d spend hours with Mickey going over drum stuff, and then we’d play full rehearsals with the band. Every day.

In the studio, we recorded “The Other One,” “New Potato Caboose,” “Alligator,” “Turn On Your Love Light,” “Born Cross-Eyed,” and some others. They didn’t sound quite right just yet but we were basically just demoing them. We planned to react to the frenzied and frenetic pace of our debut album by really taking our time with this one until we got it right.

So we traveled to New York City in mid-December and set up camp there for a couple weeks, moving into a friend’s house in Englewood, New Jersey. We’d record all night, every night, at two separate studios in Manhattan. At first, David Hassinger was behind the knobs again but he quickly lost patience with us. Maybe he thought he could cut our follow-up album in a few days’ time, like he did with the first one. He was wrong. Again.

When Weir asked Hassinger to reproduce the sound of “thick air,” Hassinger bolted. He quit. He couldn’t handle us. He wasn’t alone in that. We went through a number of engineers and even studios, in both L.A. and New York. Phil could get rather abrasive and the rest of us backed him up because we were chasing after the idea of a perfect album, having just released a debut that none of us were really all that wild about. Phil became a liability in the eyes of our record label because he had a temper, but he also had a point: You should love your albums. We didn’t love our first one and this was our chance to fix that.

Going into the studio, any studio, was always really hard for me, because it felt contrived. I’m guessing my bandmates all have similar feelings about that because we were never able to make our best music in a studio.

So, yes, you should love your albums, and although we were struggling with that, we could all agree that we loved our live shows. We were playing them fast and furious at this point—in 1967 we conquered all the Bay Area ballrooms. We built off our success from the year before and started to reach out to the great beyond. Wherever we went, we gigged, and we gigged wherever we went. So, naturally, we set up some shows during our time in New York, including a two-night stand at a tumbledown room on Second Avenue called the Village Theater. Snow leaked in through the roof one of those nights and I needed to wear gloves just to get through the gig. When we returned there half a year later, Bill Graham had taken over the place and transformed it into the Fillmore East. To this day, the Fillmore East remains one of New York’s most storied venues, even though it was only open from 1968 to 1971.

Warner Brothers wasn’t very happy with us, but what did we care? Our record contract permitted us an unlimited amount of time in the studio, and we had fought for that unusual clause for a reason. My, how things have changed—there are stories these days of some bands taking a decade or more between releases. With the album that became Anthem of the Sun, we’re talking about a matter of a few extra months. Granted, we burned through a lot of studio time, and that came with a hefty price tag, but we were footing the bill for that. As is standard practice, the label fronted our expenses but we had to recoup them before turning a profit. So they could piss off. We retreated back to San Francisco at the start of 1968, and although we weren’t empty-handed, we had less than half an album and a handful of fragments. Clearly, we were still in an experimental phase.

Back home, we were happy to get back to what we loved and knew best—playing music. Live. In front of people. At some point, it must’ve dawned on us, “Hey, we can’t get the sound we’re looking for in the studio, but we sound great live, so why not overlap the two?” Without a professional producer willing to stick it out with us, we brought in our new soundman, Dan Healy—Bear’s replacement—and went for it. When I say we went for it, I mean we really went for it. Instead of turning the album into a live release, we layered different versions of the same song on top of each other until the notion of infinite possibility revealed itself. One key reason why Deadheads kept coming to show after show after show was that no two performances of a song were ever the same. We couldn’t have done that anyway, even if we tried—but of course, we weren’t trying. Improvisation was both our aesthetic and our ideal, and it was something that we could explore only through experimentation. There just was no blueprint for this stuff.

Many bands, including jam bands, talk about their studio releases as picture-perfect postcards, where they capture the band at a moment in time, and where they capture the songs in their most realized form. But we were always a different band from one second to the next, and a song like “The Other One” was only realized when it was shape-shifting into something else entirely. A postcard wouldn’t work—we were a moving picture. But how do you capture that?

Phil and Jerry were the ones who figured out that we could exploit studio technology to demonstrate how these songs were mirrors of infinity, even when they adhered to their established arrangements. It’s the old paradox of “improvisational compositions.” Jazz artists knew all about the balance between freedom and structure, but a few rock bands were now catching on. Most rock bands, however, tended to head in an opposite direction, afraid of the uncertainty of improvisation. We decided that Anthem of the Sun was going to be our statement on the matter.

So, in the Spring of 1968, we started recording all of our shows. We played the album sequence live, twisting and turning it different ways every time, and at every stop along the way. We did a short package tour of the Pacific Northwest with Quicksilver Messenger Service called “The Quick and the Dead,” and we focused our set heavily on the proposed album material. We also couldn’t resist playing our new exploratory showpiece—“Dark Star”—often, taking it to different cosmic places every time, although that tune would be even more problematic to capture on a studio release. We realized this.

We played Jerry’s song, “Cryptical Envelopment” sandwiched around “The Other One,” without a break in the music, and we played the hell out of “Alligator” and “Caution” and even “New Potato Caboose” and “Born Cross-Eyed.” Then, Jerry and Phil went into the studio with Healy and, like mad scientists, they started splicing all the versions together, creating hybrids that contained the studio tracks and various live parts, stitched together from different shows, all in the same song—one rendition would dissolve into another and sometimes they were even stacked on top of each other. The result was Anthem of the Sun, which was finally released on July 18, 1968. It was easily our most experimental record, it was groundbreaking in its time, and it remains a psychedelic listening experience to this day.

Warner Brothers wasn’t so sure about it at first, but I think they got over it. Initially, label president Joe Smith was rather displeased that the album wasn’t ready by February; he wasn’t impressed with our attitude or our methods, and he was fed up with reports of Phil’s temperament. We gave him no choice but to deal.

Just as Jerry proclaimed, “This is the Grateful Dead!” the night Mickey Hart first played with us, the same could’ve been said after the first time anyone listened to Anthem of the Sun. It was the Spring of 1968 and we had arrived.