CHAPTER TEN

THE OVERSEAS ENIGMA

Qua ducitis adsum.

A number of earlier researchers have claimed to find links between the Sinclair family of Scotland and the ancient Norman Saint-Clairs, who were alleged to be connected with a Priory of Sion event which supposedly took place at Gisors. At one time the Knights Templars had their Scottish headquarters close to the Sinclair estates at Rosslyn. The chapel at Rosslyn dating from the middle of the fifteenth century has traditional associations both with Rosicrucianism and Scottish Freemasonry. Thory's early nineteenth century history of Freemasonry and Gould's later work on the same theme both indicate that from a very early date in the seventeenth century the Sinclairs were regarded as the hereditary Grand Masters of Freemasonry in Scotland. How many of the Templar secrets actually found their way to Rosslyn is anybody's guess — but it is a very interesting area of speculation.

Slane is one of the most attractive and interesting villages in Ireland. It stands where the road from Derry to Dublin cuts the road which links Drogheda with Navan. The village layout is quaintly octagonal, and one folktale says that the four fine Georgian houses which are such a prominent feature were originally designed to house the Priest, the Doctor, the Magistrate and the Constable. Not far away are the enigmatic ruins of Castle Dexter, believed by some historians to be of Flemish origin, or, at least, to have belonged to the Fleming family — an interesting possible continental connection.

There are two very curious stone coffin lids set on either side of the church door, on one of which the inscription appears to have been cut as a mirror image reminiscent of the Shepherd Monument at Shugborough and the chess boards on which the final knights' tours have to be executed to decipher the “blue apples” code.

The Hill of Slane, a mile from the village centre, has strong associations with St. Patrick himself. Erc, the first Bishop of Slane, was a good and courageous man who defied the local druids in order to give due honour to St. Patrick. Erc's tomb still stands in the ancient graveyard at the top of the hill, close to the monastery which he founded there, on the site of which a small Franciscan friary was later built. It was to the original monastery founded by Ere, however, that the infant King Dagobert II was sent when Grimoald, the Mayor of the Palace, attempted to usurp the throne of Austrasia for his own son Childebert in 653. The other Austrasian lords arrested Grimoald and sent him to Paris where King Clovis promptly executed him. According to evidence provided by Archdall and Mezeray, Dagobert II was recalled from Slane in 674 and reigned for almost three years before being assassinated.

The enigma of Rennes now moves to England. Our chapter on codes and ciphers has already touched briefly on the Shepherd Monument at Shugborough Hall in Staffordshire, and its puzzling inscription, but there is still more to be said about the significance of this strange marble bas-relief which so curiously reverses Poussin's original composition, Admiral George Anson died in 1762 and such was his fame that a poem to honour his memory was read in Parliament. This is recorded in Erdeswick's Survey of Staffordshire published in 1844:

Upon that storied marble cast thine eye.

The scene commands a moralising sigh.

E'en in Arcadia's bless'd Elysian plains,

Amidst the laughing nymphs and sportive swains,

See festal joy subside, with melting grace,

And pity visit the half-smiling face;

Where now the dance, the lute, the nuptial feast,

The passion throbbing in the lover's breast,

Life's emblem here, in youth and vernal bloom,

But reason's finger pointing at the tomb!

That stanza seems to relate quite unequivocally to the Shepherd Monument at Shugborough.

The vast fortune which Admiral Anson acquired came, ostensibly, from overseas gold. His richly exciting and adventurous life took him all the way around the world. Did he ever go to Nova Scotia or, more particularly, to Oak Island in Mahone Bay, near the fishing village of Chester? If he never went there in person did he arrange for an expedition to go there under the command of one of his trusted subordinates?

Michael Bradley's fascinating book, The Holy Grail Across the Atlantic, provides a number of important clues linking the mysteries of Rennes-le-Château with the mysteries of the Oak Island Money Pit.

Bradley discovered that there are two Oak Islands, not one, and that their relationship to each other is very curious. The better known of the two, the one in Mahone Bay, was the scene of our own research visit in 1988 to gather data for our unsolved mystery lectures and a forthcoming book. This Oak Island is close to the mouth of the Gold River, which flows south across Nova Scotia and empties into the Atlantic.

The lesser known of the two is an island no longer, although it was until the 1930's when the dyke building programme to counteract the worst effects of the great depression turned it into the tip of a peninsula. Thousands of acres of fertile land were reclaimed from the waters of the Bay of Fundy. When this northern Oak Island was an island, it lay at the mouth of the Gaspareau River. Michael Bradley goes on to tell of his discovery of what sounds very much like the ruin of an ancient castle – almost exactly midway between these two Oak Islands. It is on the central Nova Scotian water table from which the Gaspareau and the Gold River flow north and south respectively. By a curious coincidence, if you stand on either of the Oak Islands and look towards the mainland you will see the mouth of the river to your right. Follow the river and you will reach the enigmatic site of what may have been the ancient castle.

As knowledgeable old Abbé Boudet might well have written in La Vraie Langue Celtique, the old Celtic word for “oak” is duir, “right side” is de, duir meant “door” as well as “oak”. In Welsh, which is very closely related to old Celtic, derw is “oak”, drws is “door” and dwr is “water”. Bradley's etymology makes a great deal of sense: the two Oak Islands are probably clues to water-doors via the rivers on their right hand sides.

His ideas about the origin of the oak trees on the two islands are also convincing. Oaks are unlikely to be self-seeded: Bradley says acorns don't float. Supposing that you wanted to provide a clue, a marker, or a signpost, which would be obvious to those in the know but of no significance to the uninitiated. There were plenty of oak trees on the shore. They would not look out of place or odd on an offshore island — but they would not have got there without human intervention, according to Bradley. There's another Celtic-Welsh word that's worth examining en route: the word is dwyrain—it means “east”. Is that the direction from which the oak-planters came? Bradley is making out a respectable case for the existence of an important and interesting site midway between the two Oak Islands. Who built it? Why? And when?

While we were making a detailed site study of the Mahone Bay Oak Island in 1988,we had the pleasure of meeting one of the most knowledgeable writers and researchers in the area: George Young, a recently retired professional surveyor. His extensive firsthand experience of the locality leads him to a similar conclusion to Michael Bradley's about the geological origins of the Money Pit: it is a natural limestone blow hole, about seventy metres deep. At its base lies a large and mysterious cavern connected to the surrounding Atlantic and, possibly, to part of the course of a subterranean river as well. Its natural origin by no means negates the theories about something of great historical interest (and, perhaps, of great financial value) being buried there.

The recent history of the Oak Island Money Pit begins in 1795 when young Daniel McGinnis and his two teenaged friends, John Smith and Anthony Vaughan, dug into a circular, saucer-shaped depression about thirteen feet across, which Daniel had found in a clearing in the south east corner of the island. A sturdy solitary oak stood above this depression and — in some accounts — from one of its lopped branches hung a decaying block and tackle of the type used on early sailing ships.

Two feet down the boys discovered a layer of flat stones, like paving stones: they were not of local origin as far as the young explorers could judge. As the boys continued their work they unearthed platforms of oak logs at ten foot intervals down to a depth of about thirty feet. At this juncture, as not a single brass farthing had yet appeared to reward them for all their heavy digging, the boys abandoned the project for the time being.

Attempts to enlist further assistance were not very successful for two reasons: first, life as a Nova Scotian farmer or fisherman in 1795 was hard and time consuming; second, Oak Island was regarded — and still is today by some of the local residents — as a place of ill-omen.

Some years before the McGinnis gang found the clearing and the top of the shaft, strange lights had been seen on the island. It was rumoured that two or three fishermen who had rowed out to investigate had never returned. Pirates, perhaps, had murdered them?

John Smith, one of the three original discoverers grew up, built a house on Oak Island and began to farm the eastern end of it. David McGinnis joined him and began farming an area in the south west.

In the spring of 1803, the three original excavators — now part of the Onslow Company led by Simeon Lynds — got down to the ninety foot level. Every ten feet, or so, they discovered yet another horizontal platform of oak logs. They also encountered coconut fibre, putty and charcoal strata: and Oak Island was a long way—2000 kilometres — from the nearest coconut trees. At the ninety foot level they found a curiously inscribed stone. Its “message” is ambiguous.

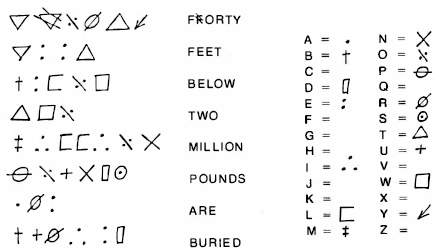

Oak Island stone

There is reliable evidence that this stone actually existed: it is mentioned in the early records left by the Onslow Company. John Smith cemented it into the fireplace of his home on Oak Island; then it was taken to Halifax by a bookbinder named Creighton, who was treasurer to another Oak Island syndicate. He displayed it in his shop window to attract investments. In 1865, a language professor from Dalhousie University in Halifax deciphered it along the lines shown in the above diagram. A friend of the authors, computer engineer Paul Townsend, reached exactly the same conclusion in a matter of minutes when he checked it for us a few months ago.1

The problem is that the stone itself vanished in 1919 when the Creighton bookbindery was closed and has not been seen since. Harry Marshall, however, the son of a former Creighton partner, swore an affidavit regarding the stone on March 27th, 1935. He said basically that the stone was two feet long, fifteen inches wide and ten inches thick. It was as dark and hard as Swedish granite and very finely grained. When Harry Marshall had seen it there had been no trace of any inscription on it — either carved or painted — but he also testified that it had been used as a base block for beating leather in the bookbindery for over thirty years. That would have effectively obliterated any message it might once have carried.

The second theory of the inscription's meaning was brought to our attention by George Young who has made detailed studies of the local coast line and tidal levels over a number of years and has concluded that within historical times the water was at least thirty feet lower in the Oak Island area than it is today. His researches have led him to conclude that the earliest visitors from the old world may well have been Phoenician or Egyptian merchants. He is of the opinion that these early visitors would have established friendly relationships with the local Amerindian tribes, and that far more Micmac words than coincidence can account for are very similar indeed to Arabic and Egyptian words. If, as is certainly possible, these earliest Mediterranean seafarers reached Nova Scotia centuries before the Christian Era, there is no reason at all why later parties should not have repeated their epic voyage.

Suppose, for the sake of argument, that a party of religious refugees — spiritual fore-runners of the “Mayflower” men — left Egypt or North Africa in the fourth or fifth century to escape the ravages of the Vandals. It is well known that Gaiseric the Vandal was responsible for prolonged and vicious persecution of the Christians in the second half of the fifth century. Early in the sixth century the Vandal Empire covered much of the north coast of Africa immediately south of Sardinia, including the city of Hippo, where Bishop Augustine, the Christian philosopher, had flourished from 396 to 430.

George Young's investigations into the Oak Island mystery have led him to hypothesize a small group of Coptic Christian refugees settling there almost 1500 years ago under the leadership of an Arif, or sub-Priest. When this holy man eventually died, he was buried at the bottom of the Money Pit, with log platforms arranged at regular intervals to prevent the weight of the re-filled clay from crushing his sarcophagus. Young's fascinating ideas are powerfully reinforced by the work of Professor Barry Fell of Harvard University who says that far from being written in a simple English language alphabet code, the inscription on the mysterious stone was carved out in a Libyan script, and the words form part of a Libyan-Arabic dialect. Professor Fell translates the inscription as a religious exhortation to the group of refugees:

“The people will perish in misery if they forget the Lord, alas. The Arif, he is to pray for an end or mitigation to escape contagion of plague and winter hardships.”

George Young compounds an already strange mystery by referring to what several historians accept as the authentic remains of a mid-fourteenth century Norse church at Newport, Rhode Island. Others believe the building to have been a medieval lighthouse.

The Italian adventurer Giovanni de Verrazano visited the site in 1524 during his coastal explorations from Florida to Labrador. He recorded that the people he met on Rhode Island were very light-skinned and highly civilised: but they had no knowledge of who had built the ancient stone tower.

According to Young's research, a party of considerable size reached the Oak Island area round about 1384. Were these the same men who had built the Church (or lighthouse?) on Rhode Island? Had they, or their descendants on Rhode Island, inter-married with the indigenous Amerindians in that neighbourhood to produce the friendly and civilised people who welcomed Giovanni in 1524?

In 1946, Magnus Bjorndal and Peer Loofald translated some Norse runes found in the Rhode Island tower. These runes claimed that the tower had been “built as the Bishop's seat,” i.e., the “Cathedral” of his “diocese”. Suppose that instead of — or in addition to — a Coptic Christian Arif, a fourteenth century Norse bishop lies buried in the Oak Island Money Pit?

To resume the narrative of the Pit itself: at the ninety foot level the Onslow Company found and removed the mysterious dark stone.

The problem with the transliteration of the coded stone's message into English is that it's too simple. It seems much more likely that that message was concocted in the 1860's and then either cut or painted on to the stone to tempt potential investors. Suppose, however, that the original 1803 stone contained something like the strange Libyan-Arabic script which Professor Fell deciphered, or, at least, a far more complex code than the rather facile and superficial “FORTY FEET BELOW…” message. What if that stone was treated rather like a lithic version of a palimpsest in the 1860's: some trivial message having been superimposed for commercial reasons over an original and ancient one which really was of interest and significance?

Having located and removed the stone the Onslow team kept on digging. At ninety-three feet they were excavating two tubs of water for every tub of soil. As darkness fell they probed the floor of the pit. A few feet down their crowbar struck something hard: wood, iron, treasure chests, the roof of a burial chamber? They decided to cease operations for the night.

When they returned at first light there were twenty metres of water in the pit. Bailing had no effect on it. For the time being they gave up. Returning the following year they sank a second shaft four and a half metres to the south east of the original Money Pit. This, too, flooded when the earth between the two pits collapsed. The Onslow Company gave up altogether; John Smith went on farming; the pits were filled in for safety.

In 1849 a new group, the Truro Company, had a go at the Money Pit. Daniel McGinnis had died, but Smith and Vaughan (now in their seventies) were still around, and so was Simeon Lynds of the old Onslow Company. Jotham B. McCully was appointed as drilling engineer. On June 2nd, 1862, Jotham wrote to a friend telling him what they had found. His exploratory drillings and core samples had revealed a spruce platform five inches thick at exactly ninety-eight feet (which was where the Onslow men had said it was). The auger had fallen twelve inches then gone through four inches of oak. Beneath that there were “loose objects” of some kind (treasure or the bones of a dead holy man still wrapped in his robes?) and the auger brought up three links of an ancient chain — possibly, but not definitely gold. Then came eight inches of oak (the bottom of the upper chest — or sarcophagus — and the lid of the lower chest — or sarcophagus?). This was followed by more loose metal, a further four inches of oak (the bottom of the lower chest, or sarcophagus?), and another spruce platform. These upper and lower platforms were about six feet apart. Below the deeper platform the auger encountered more loose clay, suggesting that the pit went deeper than the tomb, or treasure chamber, situated between the two spruce platforms at ninety-eight feet and one hundred and four feet respectively.

The Truro Company sank a few more holes and some of this work was done under the direction of a foreman named John Pitbladdo. He was seen to pocket something that the auger brought up and subsequently left Oak Island rather suddenly. John Gammell, a major Truro shareholder, actually saw the incident, and, when he asked what had been found, Pitbladdo said he would show it to all the directors together at their next meeting: he didn't!

Shortly afterwards, Pitbladdo and Charles Archibald, manager of the Acadia Iron Works in Londonderry, Nova Scotia, made an all out effort to buy John Smith's land: they failed, but the most probable conclusion is that the wily Pitbladdo had found something of such value in the core samples that he was prepared to stake everything — including his reputation — to gain control of the important part of Oak Island.

The Truro team were very determined. They tried again the following summer: what they discovered was a series of fan-shaped, man-made drains under layers of coconut fibre and eel grass running nearly one hundred and fifty feet along the shore of Smith's cove. These drains fed at least one flood tunnel which connected with the Money Pitabout one hundred feet down.

Whoever had built the original Money Pit, or modified an existing natural sinkhole, had created a flooding system which the best of nineteenth and twentieth century mining technology has so far been unable to neutralize.

To describe in detail every shaft and tunnel sunk by syndicate after syndicate and company after company from then to the present day would require a large and profusely illustrated volume all to itself There is no better book on the subject than George Young's Ancient Peoples and Modern Ghosts available from the author at “Queensland”, Hubbards, Nova Scotia, Canada; other excellent accounts are given by D'Arcy O'Connor in The Big Dig published by Ballantine Books of New York, and by Rupert Fumeaux in Money Pit: The Mystery of Oak Island published by Fontana.

When we were carrying out our own research on Oak Island in the Mahone Bay area in 1988, the island was a hive of industry set in a bewildering mass of old collapsed shafts, flooded diggings, abandoned workings, labyrinthine underground tunnels and enigmatic ruins. The work there is presently in the hands of the Triton Alliance Limited headed by David Tobias, and their man in charge of the island is Dan Blankenship to whom we spoke at length during our visit in 1988. It's an interesting coincidence yet again that the mystery of Oak Island is now being investigated by a team with same name as the strange characters from ancient Greek mythology who adorn the old fountain in Montazels, immediately outside the house where Saunière was born. Arcadian Shepherds in Shugborough and Tritons on Oak Island near what was once Acadia in Nova Scotia?

Another intriguing aspect of the Oak Island mystery is that several of the most active investigators and their closest associates during the 1930's—; Hedden, Blairand Harris, for example — were believed to be Freemasons of high rank. D'Arcy O'Connor records that Blair once referred to Hedden as a brother Mason in a letter to Harris, in which he expressed his deep disappointment that Hedden was postponing his explorations indefinitely. (Like many of his predecessors Hedden was running out of funds.) Is it just possible that not only some of the highest ranking trans-Atlantic Freemasons, but whatever European secret society the Bacon brothers were involved in had some special knowledge of the Oak Island mystery?

One of the most amazing Oak Island theories concerns the four hundred year old controversy about whether Sir Francis Bacon was the real author of the plays which bear Shakespeare's name. Eminent supporters of the Bacon claim have included Coleridge, the poet, and Disraeli, the Prime Minister. The argument begins with the suggestion that William Shakespeare, who probably left Stratford's free grammar school when he was only thirteen to become an apprentice to a local tradesman because the fortunes of his father, John Shakespeare, were dramatically declining, had nowhere near the necessary educational background to have written the plays that bear his name. He married Anne (or Agnes) Hathaway (who was eight years older than he was) in 1582 when he was eighteen. In 1584 he annoyed Sir Thomas Lucy by poaching on his estate and had to leave Stratford rather hurriedly. There is then a long gap in what is known with any certainty of Shakespeare's life history until 1592, when he surfaces again as an actor with some plays credited to him.

Genius, of course, is independent of formal education: leaving school at thirteen to enter the University of Life may well have sharpened Shakespeare's latent talent rather than hindered it. But the stubborn fact remains: if we are looking for an alternative author — a man of equal genius with a germane educational and cultural background in addition—; Sir Francis Bacon is a very prominent candidate.

Bacon was undoubtedly highly intelligent as well as being a very secretive and mysterious character. He was a talented all-rounder: a writer, linguist, lawyer, scientist, philosopher and statesman.

The Elizabethan court tended to look down on actors, poets and playwrights, so it was by no means rare for a courtier with literary or dramatic talent to use a pseudonym, or even to give some other real person the credit for his work. The Baconians argue that this is what happened with the plays attributed to Shakespeare: Sir Francis wrote them but attributed them to Master William. Some of the more extreme Baconians even go so far as to hint that Shakespeare was not Bacon's only pen name. They wonder if he also wrote some, at least, of the works attributed to Edmund Spenser and Christopher Marlowe. It is, undeniably, a possibility.

One major plank in the Baconian argument is that very, very few — if any — genuine, original manuscripts in Shakespeare's own hand, (or Spenser's or Marlowe's for that matter!) are known to exist. Is it not just slightly curious that they have all — or almost all — disappeared? Enthusiastic Baconians would argue that the real reason for the scarcity is that those precious manuscripts are so clearly in Bacon's elegant and distinctive hand, that they were all carefully hidden away in some very secure place at his instigation.

Dr. Burrell F. Ruth told a group of students at Iowa State College as long ago as December 3rd, 1948, that Sir Francis must have prized those original documents very highly and had, therefore, arranged for them to be hidden securely until the world had become a better place — the home of a highly civilized humanity to whom he would like the truth about his authorship to be revealed.

Bacon, as we have noted, was a scientist as well as a statesman and author. His book, Sylva Sylvarnm, describes a technique for preserving documents in mercury, and a method of creating artificial water sources not unlike the ingenious drainage systems found in Smith's cove to the east of Oak Island.

Even more curious was the expedition of Dr. Orville Ward Owen who followed what he believed to be Baconian ciphers which led him to a mysterious underground chamber beneath the riverbed at the mouth of the Riverbed in the west of England. The chamber was empty when Dr. Owen examined it, but he was convinced that certain symbols cut into the walls were Baconian. He concluded that Bacon had intended to hide his manuscripts there, then changed his mind and decided on somewhere more secure and much further away. Oak Island? There are one or two other pointers in this direction: in 1610 Bacon was one of a number of men to whom James I granted lands in Newfoundland — so he had some connection with that area; furthermore, among the many oddities said to have been found on Oak Island were a number of stone jars of old-fashioned design — and traces of mercury were alleged to have been detected in them.

Another famous name connected with Oak Island is that of William Kidd, who was hanged for piracy in 1701. He is not the strongest of contenders: the Oak Island structures seem far older and more complicated than anything a crew of privateers could have managed. However, Kidd's adventures were not so much earlier than Shugborough's Admiral Anson's. Young George was still only a child when Kidd was hanged, but Anson's epic voyage was inspired by the earlier adventures of Woodes Rogers, a daring privateer, who was a contemporary of Kidd.

There is also a strange tale told by Andrew Spedon in Rambles Among the Blue Noses which appeared in 1863. Spedon said that Kidd had a lieutenant named-Lawrence who jumped overboard and swam for it to escape being arrested with Kidd when their ship reached Boston harbour. Lawrence is said to have been befriended and hidden by Dutch settlers, to whom, before his death, he gave the information that Kidd had left a vast treasure buried on, or near, the coast of Nova Scotia. Could there have been any remote connection between this Lieutenant Lawrence (if he was ever anything more than a figment of Spedon's imagination) and the enigmatic Lawrence family — also of American origin — who were connected with the mysterious Tomb of Arques near Rennes-le-Château?

By far the widest spread of the convoluted net of the Rennes-le-Château mystery, however, is daringly hypothesized in the stylish and elegant prose of Jean Robin, the skilled, sensitive and imaginative author of Operation Orth. In this far reaching study, Robin focuses first on Archduke Johann — or Jean — Salvator, the young Habsburg Prince who was contemporary with the tragic Rudolf of Mayerling, and who was also acquainted with both Saunière and Boudet. After the lovers' death in the hunting lodge, Johann — having assumed the name of Orth — set sail for South America and was never seen again.

Robin goes on to explain how an incredibly powerful “artefact” or “talisman” of some description was transported in great secrecy from the cemetery of Millau (a little town in the Languedoc) to Bear Island, part of the remote Spitzberg Archipelago. From there, Robin's amazing story leads to subterranean labyrinths in South America, and awesome es-chatological predictions…

The mystery of Rennes-le-Château is no more confined to that small mountaintop village than a bullet is confined to the gun in whose magazine it rests while waiting for a finger to pull the trigger.

1To reach this decipherment a minor emendment to the text of the message is necessary. The first character is a point-down triangle, and the second looks like a badly carved six-pointed star. None of the other characters, however, appears “badly carved” in any way. Eventually, I reached the conclusion that this “six-pointed star” was in fact a second point-down triangle, carved in error and promptly crossed through with two diagonal lines. When this character is ignored, the remainder of the message decodes into “FORTY FEET BELOW TWO MILLION POUNDS ARE BURIED” by a simple substitution cipher, very much along the lines of the “Dancing Men” in the Sherlock Holmes story by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. PVST