CHAPTER SIX

CODES, CIPHERS AND CRYPTOGRAMS

Ars est celare artem.

Marie de Nègre's Tombstone and the Rennes Coded Manuscripts

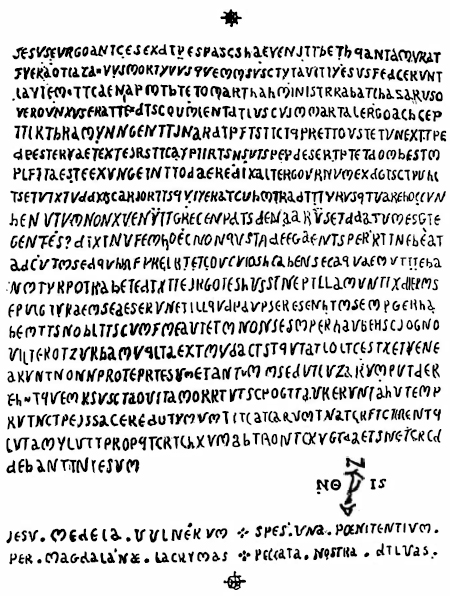

In the churchyard at Rennes-le-Château lies a broken defaced tombstone: the stone is rectangular with a pointed top. Local tradition says that Saunière himself went to the trouble of erasing the inscription because it held a vital coded message — the key, or one of the keys, to the treasure. Unfortunately for Saunière, the stone had been copied by an antiquarian before the priest found and defaced it. Here, with its odd imperfections, is the inscription:

| CT GIT NOBLeM | (a) | |

| ARIE DE NEGRe | (b) | |

| DARLES DAME | (c) | |

| DHAUPOUL De | (d) | |

| BLANCHEFORT | (e) | |

| AGEE DE SOIX | (f) | |

| ANTE SEpT ANS | (g) | |

| DECEDEELE | (h) | |

| XVII JANVIER | (i) | |

| MDCCLXXXI | (j) | |

| REQUIESCATIN | (k) | |

| PACE | (l) | |

| (P.S.) PRAE-CUM | (m) |

There are 128 letters in the inscription, and this, together with their abnormal arrangement, may be a clue to the decipherment. There are eight odd or misplaced letters. The I of “CI” in line (a) has been carved as a T. The final e of “NOBLe” in the same line is lower case. The M of “MARIE” has been left stranded on the end of the line. In line (b), the final e of “NEGRe” is the wrong size and the wrong fount. The first word in line three should, perhaps, be “DABLES” with a B not an R. The final e in line (d) is the wrong size and fount. The p of “SEpT” in line (g) is too small and has been carved low. The second C (Roman for 100) in the date in line (j) has been carved as an O. The incorrect capitals are, therefore, T M R and O; the misplaced small letters are e e e and p. These eight letters can be rearranged into MORT épée or “DEATH sword”. They can also be subjected to two minor changes and used to produce the word emprunté, which means “false”, “assumed” or “borrowed”.

Is the inscription, therefore, false? Has the gravestone been “borrowed” for the purpose of transmitting a coded message? To arrive at emprunté, we turn one of the lower case e's on its side and use it as an n. The wrong fount e's as they appeared on the stone were similar to n's if turned sideways. The misplaced O in the date has to become a U, but if we go back to the original Roman C and turn it sideways like the lowercase wrong fount e which became an n, the problem of finding the U is not insoluble. The danger here is of running into the “enthusiasm trap” as did the dedicated pyramidologist whom we mentioned in the previous chapter! There is substantial evidence that Saunière, and perhaps Bigou, too, had an irreverent sense of humour. The letters can also be arranged to form emportée meaning “she has been carted away”! Perhaps Bigou bore a grudge against Marie de Nègre.

It seems more likely that MORT épée is the clue we want. There are eight letters, four of each kind. There are eight squares per line in a chess board, and a chess board — or rather two chess boards — will feature in the later stages of the decipherment. It now becomes necessary to have some preliminary involvement with the longer of the two strange coded manuscripts which were said to have been found in, or near, the Visigothic altar pillar in Saunière's time. They will be dealt with in greater detail later in this chapter. At this juncture it is sufficient to say that this manuscript contained 140 unnecessary extra letters. Much time and effort have been expended on trying to make sense of the stone's inscription, and there is still considerable controversy over the clear text which finally seems to emerge.

In essence, students of the Rennes-le-Château mystery are broadly agreed that the vital decoding processes include the key MORT épée to decipher the message, followed by a knight's tour of two chess boards. A final step which readers can easily carry out for themselves is an anagrammatic check on the 128 letters on the stone and the 128 letters of the clear message.

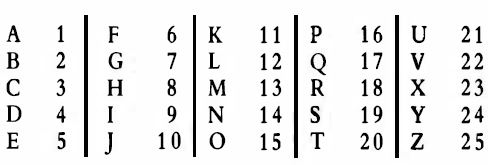

One important point must be borne in mind through the following discussion: the message which has been encoded in the tombstone inscription is in French, and the encryption procedure has used the French alphabet. This contains twenty-five letters: the letter W is not used in French and is omitted from the alphabet. With the exception of W, the French alphabet is the same as our own.

The decipherment procedure makes use of the position values of the letters in the French alphabet, counting A as 1, B as 2, and so on to Z which becomes 25:

For example, suppose that the key word is SAUNIERE and that the cipher reads:

A Q I E F M L N A Z V P E I L N

Copy the key word as often as necessary until every letter of the cipher is covered by a letter of the repeated key word.

| Cipher: | A Q I E F M L N A Z V P E I L N… | |

| Key Word: | S A U N I E R E S A U N I E R E… |

To begin deciphering the message, find the position values of the letters A (the letter from the encoded message) and S (the first letter from the keyword). These are 1 and 19 respectively. Their sum, 20, is the position value of the letter T, which becomes the first letter of the plaintext. The second enciphered letter is Q (17), the key letter is A (1), giving 18 (R) as the second plaintext letter.

In the third case, the position values are 9 (I) and 21 (U) which sum to 30. Since this runs off the end of the alphabet at 25, we begin again at A (26) and count round to E (30). Alternatively, 25 may be subtracted from the sum to give 5 (E).

Proceeding thus to the end gives the decoded message Trésor est à Rennes…

| Cipher: | A Q I E F M L N A Z V P E I L N… | |

| Key Word: | S A U N I E R E S A U NI E R E | |

| Clear: | T R E S O R E S T A R E N N E S… |

The longer of the two coded manuscripts said to have been found in the Visigothic altar pillar in Saunière's time contains 140 superfluous letters. The twelve central letters are raised: so the cryptographer rejects them. This leaves 128 to work on: exactly the same number as were carved on to the tombstone of Marie de Nègre: presumably by Abbé Bigou circa 1781. One school of thought approaches the problem by taking these letters and using them in conjunction with the inscription from the tombstone. Another approach concentrates on the inscription alone. In either case, it is considered important to lay out the letters on two chess boards and make a knight's tour of both.

The 128 letters in question run as follows:

V C P S J Q R O V Y M Y Y D L T P E F R B O X T O D J L B K N J F Q U E P A J Y N P P B F E I E L R G H I I R Y B T T C V T G D L U C C V M T E J H P N P G S V Q J H G M L F T S V J L Z Q M T O X A N P E M U P H K O R P K H V J C M C A T L V Q X G G N D T

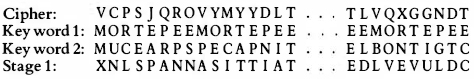

The complication here is that two key words are used. The first is MORT épée, which has to be written sixteen times below the letters. The second keyword is the whole of the inscription from the gravestone of Marie de Nègre including the “(P. S.)” and “prae cum”. To complicate matters still further, this keyword has to be used backwards. We start in the bottom right-hand comer and work from right to left and from the lowest line upwards. The full set up is:

To decode the message, each letter of the cipher must have the position values of the corresponding letters in both keywords added to its own position value. Thus the first letter is V (22) + M (13) + M (13) = 48 (X second time round), the second letter is C (3) + O (15) + U (21) = 39 (N second time round). Note that it is now possible to complete two passes through the alphabet: this happens on the sixth letter, which is Q (17) + P (16) + R (18) = 51 (A third time round).

Proceeding right through the message gives the following:

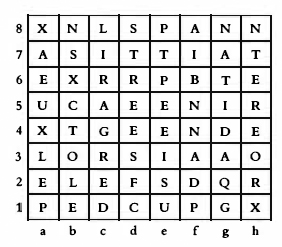

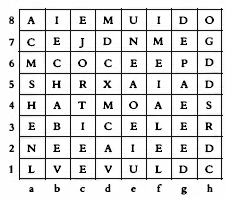

X N L S P A N N A S I T T I A T E X R R P B T E U C A E E N I R X T G E E N D E L O R S I A A O E L E F S D Q R P E D C U P G X A I E M U I D O C E J D N M E G M C O C E E P D S H R X A I A D H A T M O A E S E B I C E L E R N E E A I E E D L V E V U L D C

This text is in fact a perfect anagram of the letters on the tombstone, but it is unreadable because the letters are not in the correct sequence. We now introduce the knight's tour.

In chess, the knight moves one square laterally followed by one square diagonally. An alternative way of considering his move is to say that he moves two squares laterally followed by one square at right angles to his original direction. During the game a knight can pass over any other piece in his path, provided that his landing square is either empty or occupied by an opposing piece which he then takes.

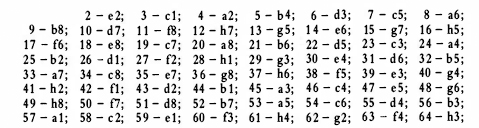

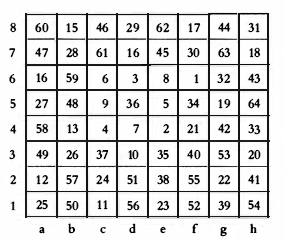

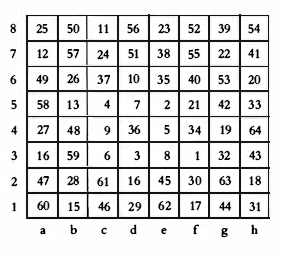

There are many ways of working out the knight's tour — a kind of chess problem in which the object is to cover every square on the board using the legal moves of a knight and visiting each square once only.

Modem chess notation is algebraic. The co-ordinates for each square are built up from the lower case letters a — h and the Arabic numerals 1 – 8. Each player should have a white square at the right-hand comer of his back rank. A line of squares running directly from player to player is known as a file, and these files are given the letters a — h, starting with a on the left of the player with the white pieces. The ranks are numbered from the white player's back row (1) to the black player's back row (8).

The solution shown on the next page begins on the white king's knight's starting square, gl. The rest of the moves are:

In the grid below, the starting square (gl) is numbered “1”, the square reached by the first move (e2) is numbered “2”, and so on until square 64 (h3). Note that a single valid knight's move links square 64 back to square 1 – this tour is described as “circular” or “re-entrant”.

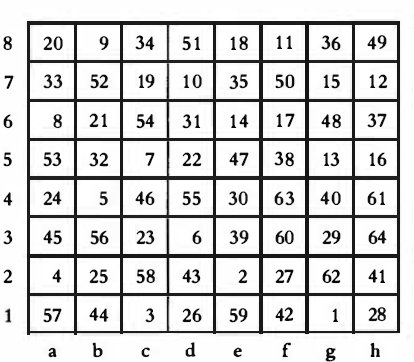

The above is one example of a knight's tour. There are many millions of other possible solutions to this problem, some of which form magic squares when written out as shown above. To complete the decipherment of the message we begin by writing out the decoded text on two chessboards, filling up the left board then the right:

On two further chessboards we fill in the knight's tour solutions. The solutions shown below are mirror images of each other. The decipherment is obtained by laying out the letters in the order in which the knights' tours proceed.

We begin with the left-hand board, and find the first move of the knight's tour – square f6. In square f6 of the letter grid we find the letter B, which becomes the first letter of the decode. Knight's move 2 is square e4; letter grid square e4 contains E. We continue through all 64 squares of the left-hand board, taking the letters in the order determined by the knight's moves. Having exhausted the left-hand board, we proceed to the right-hand board and continue in the same way.

The final message reads:

BERGERE PAS DE TENTATION QUE POUSSIN TENIERS GARDENT LA CLEF PAX DCLXXXI PAR LA CROIX ET CE CHEVAL DE DIEU J' ACHEVE CE DAEMON DE GARDIEN A MIDI POMMES BLEUES

The literal translation is:

SHEPHERDESS NO TEMPTATION TO WHICH POUSSIN AND TENIERS KEEP THE KEY PEACE 681 WITH THE CROSS AND THIS HORSE OF GOD I REACH THIS DEMON GUARDIAN AT MIDDAY BLUE APPLES

Bremna Agostini, whose knowledge of idiomatic early languages is considerable, has suggested some quite startling alternatives. Instead of SHEPHERDESS WITHOUT TEMPTATION Bremna has suggested THE DOG WITHOUT FORM OR SUBSTANCE…and thinks that it might mean Cerberus guarding the passage of the Styx. MIDI, she says, can mean mid-day or The Midi, the region of France around Rennes-le-Château. ACHEVE could also mean DESTROY or KILL. BERGERE can mean an easy chair, perhaps even a throne? Even more curious is her suggestion that in archaic French, CLEF or CLE could mean crown. CHEVAL can at a push mean SUPPORT, in the sense that a clothes “horse” supports clothes. The French verb chevaler means to “prop”, or “shore up”. GARDIEN can also mean keeper, door-keeper, trustee, warden, or even the Superior of a Franciscan Religious House! Gardien(ne), used adjectivally, can mean tutelary as well as guardian, with perhaps an edge of tuition along with the implied guarding, or protecting. Rennes-le-Château has an official gardien, as have similar French villages of comparable size. Is there anything in the code relating to the work of such an official? POMMES has a far wider range of meaning than simply “apples”. It can be a knob or ball, the head of a walking cane, etc. It is possible that POMMES BLEUES refers to the huge grapes in another of Poussin's paintings, with a mountain background very similar to that near Rennes-le-Château.

The mists begin to clear when the shepherdess of the coded message is linked with Nicolas Poussin, the painter. When Eugenio d'Ors wrote about this enigmatic artist he said, “There always have been and always will be certain truths, aristocratic truths, which it is a privilege to know.” This theme — that Poussin was one who knew strange secrets — is amplified in a mysterious letter written to Nicolas Fouquet, France's very wealthy and powerful Minister of Finance during the reign of Louis XIV. Fouquet's younger brother had been entrusted with a secret mission to Rome in the spring of 1656. Here he delivered a message to Poussin, and on April 17th wrote the following report to his elder brother:

“I have given to Monsieur Poussin the letter that you were kind enough to write to him; he displayed overwhelming joy on receiving it. You wouldn't believe, sir, the trouble that he takes to be of service to you, or the affection with which he goes about this, or the talent and integrity that he displays at all times.

He and I have planned certain things of which in a little while I shall be able to inform you fully; things which will give you, through M. Poussin, advantages which kings would have great difficulty in obtaining from him and which, according to what he says, no one in the world will ever retrieve in the centuries to come; and, furthermore, it would be achieved without much expense and could even turn to profit, and they are matters so difficult to inquire into that nothing on earth at the present time could bring a greater fortune nor perhaps ever its equal.”

What did young Fouquet mean by that letter? What strange secrets had Poussin revealed to him — if, in fact, he had actually got that far and was not merely holding out the promise of some great revelations to come. The decipherment of the parchment is certainly “very difficult to enquire into” if that's what Poussin was getting at, but, having been deciphered what does it tell us? Poussin may well have known the deep meanings behind its enigmatic phrases — if there really are any. One of the disconcerting questions that comes to the researcher's mind in this area of the investigation is that the enormous complexity and difficulty of the code seems to hide almost nothing. It is as though a massive pyramid primed with intricate booby traps, falling stones, spring-loaded spears and trapdoors over chasms hid only the mummified remains of Tutankhamun's cat wrapped in his mother's shopping list.

The investigator is tempted to read the BERGERE PAS DE TENTATION…message and come away thinking “So what?” But is this the double (or even triple) bluff in this whole anfractuous affair? Are we supposed to do something further with the BERGERE PAS DE TENTATION letters to reveal a clear and vital clue to the real mystery? Simple and unambiguous directions, perhaps, for finding a chest full of Merovingian treasure? The Elixir of Life? The Philosopher's Stone? The Emerald Tablets of Hermes Trismegistus? Some alien artefact from Atlantis or a distant galaxy? Even the Holy Grail itself?

The shorter of the texts appears to be an inaccurately copied version of an episode recorded in Luke 6: 1-4, Matthew 12: 1-4 and Mark 2: 23-26. Jesus and his disciples are walking through the fields on the sabbath day, rubbing the ears of corn in their hands and eating the grains. The Pharisees criticize them for “working” (that is, threshing corn!) on the sabbath. Jesus replies that King David once took the sacred shewbread from the altar and gave it to his hungry followers. He adds that the Son of Man (a title he frequently uses to describe himself) is lord of the sabbath.

By reading the raised letters we read:

A DAGOBERT II ROI ET A SION EST CE TRESOR ET IL EST LA MORT

“To Dagobert II, King, and to Sion, is this treasure, and he is there dead [or: and it is death]”.

At the start of the parchment there is a curious triangle, resembling the legs of the Hanged Man in the Tarot. It could have a number of symbolic meanings: the three sides may represent the Trinity; the mark in the centre could mean “one in three”; there is a character outside the triangle which might either be a Greek omega (the last letter in the Greek alphabet) or the Arabic 3, or M for Mary — depending upon the angle from which it is viewed. The triangle may be a stylized linear form of the Greek alpha (the first letter in the Greek alphabet). The combined religious symbolism might then represent God as the Trinity (Three in One and One in Three) and as Alpha and Omega (the Beginning and the End).

This triangle could also be one of the keys to the decipherment of the curious text which follows. By drawing a triangle as shown in the illustration and taking the raised letters:

| 1 5 7 9 8 6 2 4 3 10 |

| a d a g e i r a c o |

which occur inside that triangle, it is possible to form:

arcadia ego

The top line of the message inside the triangle begins with et and ends with in. Adding these words to the anagram produces our by now familiar phrase:

Et in Arcadia Ego

Leaving the triangle message and passing to the four bottom lines, we find that their last letters, read vertically, produce the word SION in block capitals. The P S at the end of the message may refer once more to the mysterious Priory. Redis, in a strangely isolated position in the centre of the lower right-hand quarter of the document, probably refers to the ancient name of Rennes-le-Château.

As we have already noted it is possible to translate et il est la mort either as “and he is there dead” (taking la as là there) or as “and it is death” (where la is the ordinary definite article the). If the latter is correct, what is the nature of the mortal danger which lurks near the treasure?

The tortuous and confused annals of alchemy have always stressed the dangers inherent in alchemical processes. The only method of performing transmutation known to modem science is by radiation bombardment. The high-energy particles required would be lethal for an unshielded operator. Only by the wildest stretch of the imagination dare it be suggested that some ancient alchemist found a sufficiently powerful natural radioactive energy source by accident, that he used it for transmutation and that he finally passed the hazardous secret to the Cathars (great healers who might have attended the dying alchemist in his last hours). Did the Cathars in turn pass it on to secret disciples after the fall of Montségur? Did it go from those secret disciples in Aude or Razès (parts of the Midi) to the noble and ancient Blanchefort family with their castle near Rennesle-Château? Was it passed from the Blancheforts to the Templars and from them to the Priory of Sion? However unlikely, it is a possibility that we have to consider along with more probable answers.

The second and longer manuscript is an equally inaccurate Latin rendering of John 12: 1-11. Here we take the decoding technique referred to in detail previously, pinpoint the 140 letters which do not appear to fit this passage, remove the twelve central ones and use the remaining 128 in conjunction with the position value cipher and the knights' tours of the two chess boards.

In addition, there are eight very small letters occurring randomly in the second, third, fourth, sixteenth, seventeenth, nineteenth and twentieth lines. These eight letters spell Rex Mundi, “king of the world”. The Cathars believed that the earth was in the hands of an evil deity whom they called Rex Mundi. The peculiar subscription to the document may be meant to represent Adonis as well as Sion in reverse. In Greek mythology, Adonis was a handsome youth with whom the goddess Aphrodite (Venus), fell in love. He was the son of Cinyras, King of Cyprus, and Myrrha. Adonis was fatally wounded by a wild boar: curiously, Abbé Boudet mentions the sanglier—“the wild boar” — on pages 298 and 299 of his mysterious book. The anemone flower was said to have sprung up where his blood soaked into the earth. He was restored to life by the magic of Proserpine and thereafter spent six months of the year with her in the Underworld and the remaining six months with Aphrodite. This is evidently an aetiological myth to explain the seasons; it is similar to the myth of Proserpine, or Persephone, herself, and the six pomegranate seeds which confined her to the Underworld with Pluto, or Hades, for six months of the year. The cult of Adonis, as a seasonal nature spirit, was widespread in Syria and the Middle East, where he was known as Thamuz. Did the Templars encounter his worship there and amalgamate it with the Cathar ideas of Rex Mundi? The strange homed statue in the church at Rennes-le-Château could represent the demon Asmodeus, or a nature-spirit like Pan. Could Adonis, god of the seasons, be identified as one and the same being as Rex Mundi, god of the earth? Adonis died, and was resurrected by the agency of Persephone, who subsequently enjoyed a relationship with him in addition to her relationship with Hades. Adonis in turn spent half his time with Proserpine and half with Aphrodite, his sex goddess. The symbolism of Adonis has two main themes: sexual relationships and resurrection. These two themes lead back to the selected passage from John's Gospel, and from there to Rennes-le-Château. John 12: 1-11 contains the story of how Jesus stayed at the villa of Mary and Martha in Bethany, where Lazarus, whom Jesus had resurrected, was among the guests. Mary anointed Christ's feet with the very expensive ointment of spikenard and wiped them with her hair. Judas Iscariot complained that the ointment could have been sold and the proceeds given to the poor, but Jesus praised Mary's generous action and related it to his own impending death.

There are certain early Christian traditions — though they are by no means conclusive — that Mary of Bethany, Mary Magdalen and “the woman who was a sinner” were one and the same person, and that she might also have been the woman whom Jesus saved from the Pharisees who were intending to stone her for adultery. (Related in John 8: 1-11, and mentioned earlier with reference to the statue in the church.)

Did the middle-aged Bérenger Saunière have a sexual relationship with his attractive eighteen year old housekeeper, Marie Dénamaud? She certainly shared the secrets of his mysterious wealth: how close were they in other ways? His church was dedicated to Mary Magdalen; the house he built with the wealth he discovered was called the Villa Bethania. Above the ancient Visigothic pillar which allegedly guided him to his fortune in 1891, he placed the statue of the Virgin Mary with the carved inscription Penitence! Pénitence! The large mural along the church's west wall entitled The Mountain of the Beatitudes is also called Terrain Fleuri, “The Land of Flowers”. The hill on which Jesus stands in this painting is certainly covered with flowers as we have already noted: some of those flowers could well be anemones — the blood of Adonis? Saunière may be saying that there is a connection between Adonis, the resurrected flower-god and the strange source of wealth waiting to be tapped at Rennes.

The Tarot, or Putting Two and Two Together to make Twenty-Two

If the codes in stone and parchment are obscure and mysterious, they are no more inscrutable than the Tarot — and the Tarot may also hold clues to the treasure of Rennes-le-Château. The Tarot, sometimes called the Tarocchi, is a pack of seventy-eight cards. There are four suits of fourteen cards each; the cards of each suit are the same as those of standard playing cards with the Cavalier as an additional court card in each suit. These fifty-six cards comprise what is called the Minor Arcana, or “lesser mystery”. There are also twenty-two curious picture cards bearing symbolic designs and known as the Major Arcana, or “greater mystery”. Twenty-two is a very strange number indeed.

Apart from the twenty-two cards of the Major Arcana in the Tarot it was in 598 B.C. that Solomon's Temple was destroyed: 5 + 9 + 8 = 22. July 22nd is the Feast of St. Mary Magdalen. Dagobert II was assassinated in 679: 6 + 7 + 9 = 22. The unfortunate Jacques de Molay who was burnt at the stake was the twenty-second Grand Master of the Templars. The French transliteration of Christ's cry from the cross — Elie, elie, lamah sabactani—contains twenty-two letters and is also the opening verse of Psalm 22. On January 22nd, 1917 (2 + 2 + 1 + 9 + 1 + 7 = 22), Bérenger Saunière died…

Just a string of curious coincidences…?

Back to the Tarot! The first Tarot suit is shown as sticks or batons. It is equivalent to diamonds in ordinary playing cards. Some authorities interpret the symbol as a magic wand; others regard it as a sceptre. The second suit is known as cups, goblets orchalices, and corresponds to hearts in the normal pack. The third suit consists of swords, and is equivalent to spades; the fourth suit has a circular emblem, and is variously described as coins, circles or pentacles.

The twenty-two cards of the Major Arcana are very complex, and several thousand words could be devoted to a description of each of them, together with an explanation of their elaborate symbolism. One or two brief examples will serve to illustrate the point. Card number one is called the Juggler or the Magician. He stands in front of a table full of magical devices. In some versions of the Tarot he looks almost like a priest presiding over a sacred celebration at the altar. One hand holds a wand in the air, the other points to the earth below his table. He wears a wide-brimmed hat, known to the medieval world as a “cap of maintenance”. The posture of his body and limbs represents the Hebrew letter aleph. Most occultists regard him as the symbol of willpower, desire and ambition. Card number ten is called the Wheel of Fortune. It has seven spokes and rotates between two vertical supports, shown as mystical rose-trees in some versions. A blindfolded figure of Fate turns the wheel, while human beings ascend and fall. The card symbolizes chance or fortune, good or bad luck.

The origins of the cards are mysterious and uncertain. At one extreme a claim is made for their origin in China over 6,000 years ago. There are also Egyptian and Babylonian claims, and Jacques Gringonneur, the astrologer, is credited with having invented the Tarot in 1392 to amuse Charles VI, known as “Charles the Foolish” (born 1368, reigned 1380-1422) but it is more likely that Gringonneur merely added to, or embellished, a much older pack.

The most probable connection between the mystery of Rennes-le-Château and the Tarot would seem to lie in Saunière's reported visits to various experts in Hermeticism when he was looking for help with decoding the manuscripts and tombstones. Most students of the occult have encountered the Tarot cards, and the parallel symbolism would be fairly obvious. Once Saunière had been shown a pack and had that symbolism explained to him, he could have begun devising ways of incorporating Tarot clues into the subsequent decorations of his church.

The Tarot, like Rennes-le-Château, is associated with alchemy. Card number twenty-one, the highest card, the World, shows a man, a bull, a lion and an eagle. These symbolize the four elements of alchemical theory: water, earth, fire and air respectively. It can be argued that the group of mysterious carvings immediately inside the church at Rennes-le-Château also represents the four elements: the demon-like Rex Mundi is King of the Earth; there is water in the dish he holds above his head; salamanders (fire creatures) writhe above the water; and angels (air dwellers) are poised above the salamanders. The earth symbol, Rex Mundi, is far larger than the rest of the figures. This may be a clue to Tarot card twenty-one — the World. The statue could be Saunière's way of drawing attention to the Tarot as one of the keys to the mystery of Rennes-le-Château.

Let us take the four suits of the Tarot: coins, swords, cups and staffs. Coins may represent the treasure; swords could symbolize the Templars and fit in with the key words MORT épée (DEATH sword) on the tombstone code; the cups, drawn in the shape of chalices, might indicate the Holy Grail, the religious element in Templarism, the Albigensian heretics, or the church at Rennes-le-Château; the staffs tie in with Poussin's painting of the “Shepherds of Arcadia”.

The tenth Station of the Cross in the church at Rennes-le-Château shows three dice arranged in an L formation. The face of the dice show a three above a four on the left and a solitary five on the right. Can these dice be manipulated to give number combinations?

First, add the digits as in numerology:

3 + 4 + 5 =12

followed by:

1 + 2 = 3

Card number three of the Major Arcana is the Empress. She symbolizes fertility and represents Gaea, Ceres Demeter, the earth mother, and that connection with Rennes is already strong. In some Tarot sets there are trees and a running river behind her: earth and water again — two of the four alchemical symbols. (There is also a small river below the tree-lined slopes leading up towards the ruins of Château Blanchefort.) Her sceptre suggests control over nature. There is a jewelled crown on her head, and in some Tarot packs her left hand points to it significantly, like the pointing fingers of the shepherds in Poussin's picture, or the pointing hand of the statue of John the Baptist in the church at Rennes.

The dice showing three and four are shown together, away from the five. Adding the three and four to produce the “mystic” number seven leads to the seventh Tarot card: the Chariot. This chariot also has alchemical significance: four columns support its canopy — each column represents one of the four alchemical elements.

The fourth card is the Emperor. Tarot writers are in general agreement in regarding him as the symbol of earthly authority or temporal power. He would be Dagobert II, or some crusading king connected with the Templars; perhaps their Grand Master.

The fifth card is the Pope (or, in some packs, Jupiter). Is this an indication that the Church guards the treasure? He holds a staff, or sceptre, in his left hand, and his right is raised with two fingers giving a benediction. He has creatures on each side of him — the traditional “sheep” and “goats” of “divine judgement”. These sheep might also be a clue to the church at Rennes, to the shepherd's staff and the shepherd's fingers pointing to the inscription on the tomb in Poussin's painting.

The twelfth card is the Hanged Man. Some authorities on the Tarot regard him as the symbol of Atys, a Syrio-Hellenic god, who stands for the sun and the seasons. Atys free is the summer solstice; bound and hanging upside down he is the winter solstice. The Hanged Man's legs form a peculiar triangle like the triangle on the shorter coded manuscript.

Should the treasure hunter follow a shadow cast by one of the Rennes district landmarks at dawn or midday on the shortest day and work out his triangle from it? Or does a shaft of light enter the church at a particular angle at midday on a special day? “Blue apples” formed from cleverly situated stained glass and sunlight? One decoding of the manuscripts suggests that the “daemon guardian” was “achieved at midday”. Could the mid-winter sun reveal something when it falls on the statue of the demon guardian, Rex Mundi, just inside the church door?

Multiplying the three and four together and adding the five gives seventeen. The seventeenth card of the Major Arcana is the Star. In fact it shows seven stars above the head of a girl who pours water into the river on the left of the card. These seven small stars are the daughters of Atlas, transformed into the Pleiades, visible at night near the back of the Bull in the zodiac. The seven celestial bodies may also refer to the seven bodies of the alchemical tradition: Sun — gold, Moon — silver, Mars — iron, Mercury — quicksilver, Saturn — lead, Jupiter — tin, and Venus — copper. The young woman on the card is identified by some authorities as Hebe, Goddess of Youth, cup-bearer to the gods and the one who supplied them with nectar. The fluid in her vases is also regarded by some traditions as the Elixir of Life, another alchemical goal. Saunière may be hinting that something infinitely more precious than worldly wealth is hidden at Rennes-le-Château.

The statuary and painting at Rennes seem to suggest that Saunière had a bizarre sense of humour; there is a mischievous, teasing element in some of the tantalizing clues he has left there. The Star is the symbol of hope — prime requisite of all treasure hunters! Could this be what he is getting at, or one of the things he is getting at, in his 3, 4, 5 dice code?1

In some ways the Rennes mystery resembles a conjuror's top hat from which one code after another springs like a rabbit — only to hop away into its labyrinthine warren before it can be caught and fully deciphered.

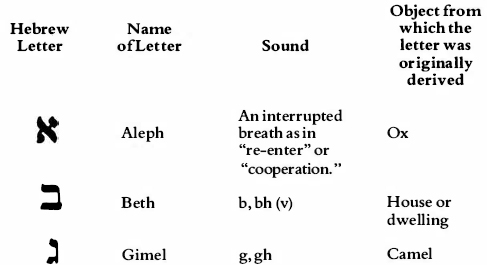

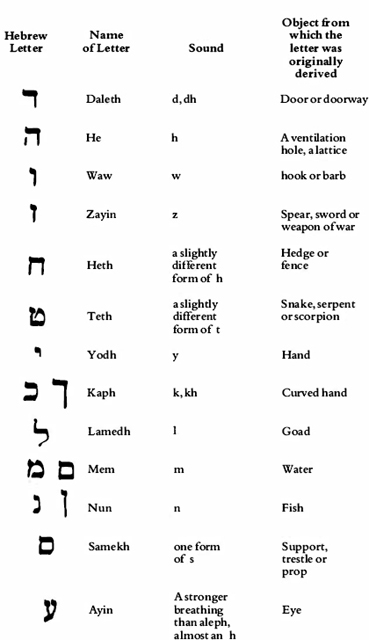

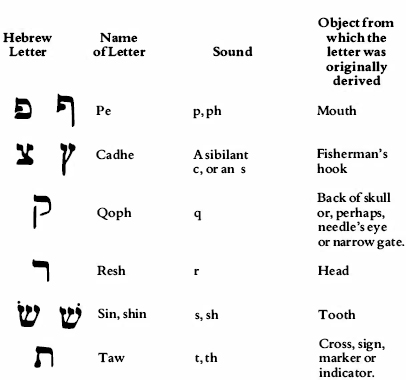

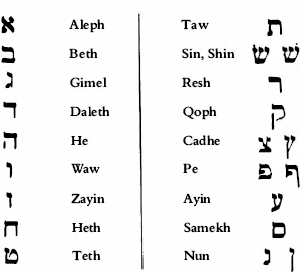

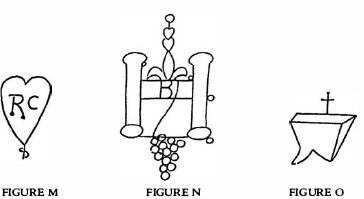

The Atbash Cipher and Baphomet

In the late sixties the authors were at Gamlingay Village College in Cambridgeshire, where Lionel Fanthorpe was the Further Education Tutor. Dr. Hugh Schonfield — author of Those Incredible Christians and several other scholarly works — was one of our guest lecturers during that period. After he had given his talk we drove him home to London where we enjoyed both his amiable company and his delicious coffee, although we would now differ strongly, albeit respectfully and affectionately, from his theological conclusions! Among Dr. Schonfield's discoveries is the Hebrew Atbash Cipher, which has to be seen in the context of the Hebrew alphabet (twenty-two letters!) in order to be properly appreciated. Its very name, Atbash, comes from the juxtaposition of those Hebrew letters from which it is formed.

The Atbash cipher is formed by folding the Hebrew alphabet in the middle so that Aleph comes opposite Taw; Beth comes opposite Shin, and so on. This produces the sounds of “a – t – b – sh”, hence Atbash.

Now the Hebrew word for Wisdom is hokhmah, the Greek word is sophia. Dr. Schonfield's Atbash cipher reportedly indicates that the word Baphomet — the name of the curious idol which the Templars were accused of worshipping — can be deciphered as Wisdom. There is wide conjecture about the physical appearance of this object and about the meaning of its name. One suggestion is that it is a Latin abbreviation spelt backwards just as the inscription on Marie de Nègre's tombstone is reversed in order to provide a position value keyword. Templi omnium hominum pacis abhas (“The father of the Temple of universal peace among men”) is abbreviated to Tern o h p ab and then read — like Hebrew — from right to left to produce the word Baphomet. Another possible derivation is baphe metios or “baptism of wisdom”.

It may safely be assumed that ninety-nine percent of the accusations laid against the Templars concerning their alleged heresy, blasphemy, idolatry, immorality and black magic were nothing more than the product of Philip IV's vicious propaganda augmented by spectacular Templar “confessions” extracted under the most extreme torture. It is infinitely more probable that the Templars revered Sophia, the Divine Wisdom, than that they dabbled in black magic and idolatry.

The Reverend Doctor Benjamin Wisner Bacon, a former Professor of New Testament Criticism and Exegesis at Yale, wrote with great authority and expertise on the theological and philosophical concept of Wisdom. He points out that in the Hokhmah, or Wisdom literature, Wisdom is seen as the Divine Spirit manifesting the redeeming love of God and going out to seek and save the lost. One vitally important aspect of Templarism was to locate and redeem knights who had fallen from their original high calling. Wisdom is personified in the Book of Job (Chapter 28), says Bacon. By the time of Philo Judaeus (30 B.C.—A.D. 40) hypostatisation has taken place and Wisdom and the Logos are synonymous, cosmological and soteriological. The mysterious Book of Enoch shows Wisdom, rejected by humanity, re-ascending to her seat in Heaven to return during the Messianic Age to bless and inspire the elect.

This personification and hypostatisation of Wisdom was rigorously resisted by the scribes of the Akiba period, during the rivalry between Church and Synagogue in Palestine (A.D. 70-135). In some Jewish texts hokhmah (wisdom) was even altered to torah (law).

The sum of the evidence here seems to suggest quite strongly that far from embracing vestigial traces of weird eastern paganism, demonology and black magic, the Templars did nothing worse than compound the idea of the Divine Logos (as in St. John's Gospel) with Sophia, the Divine Wisdom: hardly a blasphemy; scarcely a heresy; more fairly described as an emphasis of reverence — akin to the high churchman's special esteem for the Virgin Mary and the Saints or the low churchman's due regard for scriptural authority and vigorous evangelical preaching.

Curious Watermarks

As we shall endeavour to show in Chapter 7, “Magicians, Alchemists and Men of Mystery”, Sir Francis Bacon and his brother could well have been among the elect group who knew more than most about the Rennesle-Château mystery. There is also some evidence that the Bacon brothers were among those initiated into the use of an enigmatic watermark code, a small sample of which is examined below.

EXAMPLES OF THE SECRET WATERMARK CODES

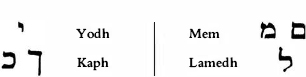

The Poussin and Teniers period was a time of vigorous interaction between Britain and the Continent. Ideas were crossing the Channel in both directions — some openly and some secretly. One of the most intellectual and most secretive Englishmen of the time was Sir Francis Bacon, and his interest in codes and ciphers is well known. It seems likely that Bacon and his brother Anthony were deeply involved in at least one secret society which had European connections. It is also possible that their society was linked with the Rosicrucians and the Priory of Sion. It seems possible, even probable, that the Bacons used watermarks not only as symbols but as codes in which messages were communicated to members of whatever secret society they had created, revived, or adapted to their own purpose. The watermark symbols themselves go back much further than Elizabethan times. Figure A, the ellipse with a cross above it, goes back to the beginnings of the fourteenth century at least. The ellipse may be meant to represent an egg, the sealed mystery, the emblem of eternity, immortality and resurrection. If it is, it ties up with the Latin acrostic ova (“eggs”) from the Shepherd Monument in the grounds of Shugborough Hall, to be dealt with later in this chapter. The cross could well be the sign of the Templars, surmounting a circle representing the world. Figure B is almost equally old and traceable at least as far back as the middle of the fourteenth century. Here the circle and cross idea is repeated, but the cross has been rotated into a diagonal position. It is now perhaps the emblem of St. Andrew, or it may be read with the upright of the original cross as a six-pointed star. Perhaps it is Davidic, the star of Sion? The lines could be the points of the compass, or it may even be part of some unknown, secret alphabet. Figure C is similar to A and B, but this time the symbol surmounting the circle is the two-armed cross of Lorraine, symbol of the Free French in the Second World War. The first three watermarks read together are reminiscent of questions in IQ tests where the testee is asked to complete the series or to distinguish one incompatible figure from the others in the group. They are equally reminiscent of electronic circuitry or computer diagrams. There is a possibility that, as is suspected of the strange rongo-rongo script of Easter Island, these watermark codes are mnemonic triggers — not decipherable in the accepted sense unless the memorized material is known to the reader.

Figure D dates from 1315; and it is thought that the ellipses here may represent the sacred scarabs of ancient Egypt. As we have already noted, the Hermetic philosophy of Trismegistus had Egyptian roots, was linked with Manichaeanism and Catharism and seems to lead in the general direction of the Templars, the Priory of Sion and Rennes-le-Château. Figure D also contains diagonal crosses on the St. Andrew pattern, unless they are six-pointed stars again.

Figure F could have considerable significance. It can, of course, be dismissed fairly superficially as the triple crown of England, Scotland and Wales (although this raises some historical problems), surmounted by the universal symbol of Christendom. Another suggestion is that it represents biblical mountains with mystic significance: Moriah, Sinai and Golgotha (or Calvary). It was at Moriah that Abraham was on the verge of sacrificing his son, Isaac, until he was told not to, and sacrificed the ram instead. The original name Moriah meant the “bitterness, fear or doctrine of the Lord”. (Genesis 22: 2 and 14). Tolkien comes close to this idea in Chapter IV of Book Two of The Fellowship of the Ring when he gives the name “Moria” to the system of underground caverns where Gandalf plunges into an unfathomed abyss while locked in mortal combat with a balrog. For the hobbits and their companions, the loss of Gandalf is exceedingly bitter; Moria is a bitter place for them — a place of sacrifice. The parallel ideas continue, however, for great things came of Abraham's willingness to sacrifice Isaac, and great things came of Gandalfs willingness to sacrifice himself The doors of Tolkien's Moria were sealed with a magic password. Gandalf, expert in such matters, explained that some doors opened only at certain times, others opened only for selected people, some had hidden locks and keys which were still required when all other conditions had been fulfilled. It is remotely possible that Tolkien's doors of Moria are a clue to the mysteries of Rennes-le-Château. Tolkien must have had good reason for describing them in such elaborate detail. The designs on the doors in his illustrations closely resemble the weird watermarks in Bacon's books. Tolkien's Moria once contained, among other things, a dead king and his treasure. Tolkien was also a member of the group known as The Inklings which included C. S. Lewis and Charles Williams whom we shall refer to again more fully in the next chapter.

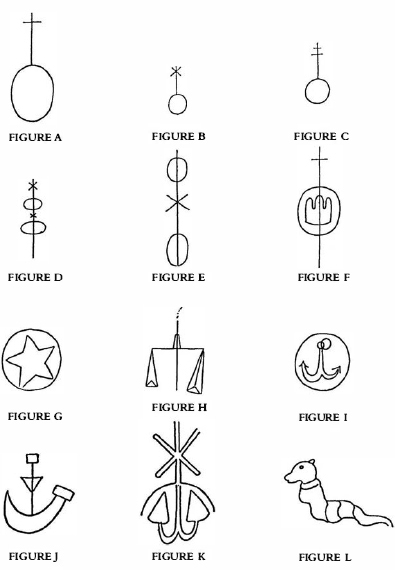

There are other remarkable similarities between Tolkien's picture of the door of Moria and the old watermarks. Figure N, for example shows a circle above two hearts with a fleur-de-lis below them and a letter B below that. The vertical columns could be meant to represent candlesticks or pillars. The door in Tolkien's picture has a pillar at each side; a tree twines around each pillar; a star is set between the trees; and an arch links the pillars at the top. Below this top arch is another arch of seven stars, the uppermost one decorating the high point of a crown. There is a hammer and anvil device below the crown. Three ancient runes, or similar linguistic symbols, also appear: one at the base (between the trees) and one in each upper comer.

Figure O shows an anvil watermark found in a Dutch account book between 1416 and 1421. A German manuscript of the fifteenth century carries a similar, but not identical, anvil watermark, which is surmounted by an incomplete Maltese cross and a letter which could be either a Roman block capital H or a greek eta, the long “ee” sound.

Double pillars, double candlesticks or gatepost watermarks can be found in Arthur Hilderson's Lectures on St. John (1628). One Latin passage in the Rennes manuscript codes is an extract from St. John's Gospel. The 1633 edition of Marlowe's jew of Malta also carries a strange watermark; it resembles two pillars joined by an arch at the top — above the arch is a diamond-shaped cluster of grapes. Is the word Jew in the title a clue to Sion yet again? And is Malta a reference to the old crusading routes and the strongholds of the Templars and Hospitallers?

There are several curious crown watermarks in the 1623 edition of Shakespeare in the British Museum. More than one of these has a broad similarity to Tolkien's crown drawn on the gates of Moria, but there are essential differences in the details.

Moving on from the possible connections between Tolkien's Moria and the Old Testament Moriah where Abraham almost sacrificed Isaac, it is worth noticing in passing that Moriah was also the site of Solomon's Temple (2 Chronicles 3: 1).

The second mystical mountain, Sinai, was the scene of Moses' communion with Yahweh and the giving of the sacred law to the Israelites. The third, Golgotha, was the site of the crucifixion.

Figure G appears to be a five-pointed star within a circle, but the lower left-hand point is unjoined. This could be a magician's pentagon, or a Jewish star pointing the way back to Sion, the Holy Land and the Crusades. The opened point in the bottom left corner is significant. It might be nothing more than an error of draughtsmanship, or a flaw in the production process, but the figure might be a leaf with an open stem rather than a star. It could be a torn hoop of paper through which someone or something has jumped like an acrobat at a fair. In some old formulas, the star with five points stood for the soul of the world. In others, a star was thought to be a heavenly messenger, a guide, a teacher, even an angel. The circle which surrounds the star is usually the symbol of the world or the earth. Could this be connected with Rex Mundi again?

As was noted in our comments on the Tarot, the seventeenth card (possibly significant in the dice code in the church at Rennes) is the Star. There are seven small stars on this card, and one larger one, which coincides exactly with the stars drawn on Tolkien's gate to Moria. The young woman on the Tarot Star is Hebe, Goddess of Youth, and in the picture on the card she is shown pouring out the Elixir of Life. This strange symbolic, allegorical trail seems to curve its tortuous way back once more in the direction of Alchemy and Rennes-le-Château.

Figure H shows a pair of scales with the tilted right-hand pan badly out of balance. This watermark, from about 1590, is visible on records in the British Museum dating back as far as 1400. Figures I,J and K have nautical connections. Each shows an anchor. J is particularly interesting in that it may also suggest the Moorish or Saracen crescent. The hull of the ship (or base of the anchor) could also be an eastern scimitar. What became of the “lost” Templar fleet? Is the ground plan of Rennes an Egyptian “Boat of the Dead”? And, as we shall ask in a later chapter, who sailed to Oak Island, Nova Scotia and what did they carry with them? The emblem is curious and ambiguous. Figure K could be the Greek Chi, the initial of Christ in Greek. It is odd to notice that the top and top-right arms are open-ended, whereas the rest are closed except for the base and the top of the anchor. About a dozen varieties of these anchor watermarks have been found, mainly in old Dutch account books, dating from the mid-fifteenth century.

Sir Nicholas Bacon spent a considerable time in Holland — what did he learn there? What old Dutch secrets might he have passed on to his sons?

Some of Anthony Bacon's correspondence is preserved in the Tennison Manuscripts in Lambeth Palace, and this is where figure L was found. It appears to be a dog-headed snake, or a dog-headed horn. Is it a cornucopia, signifying plenty, or is it a symbol of something that twists and struggles through the underground labyrinth of secret service work? Is Anthony saying here that his mind, his head, is that of a hunting dog on the scent, even though his body is twisted and handicapped by disease?

Figure M shows the heart-shaped background signifying love and brotherhood, with the letters R.C. Is this Rosicrucian imagery again? At the base of the heart is what looks like a letter S. By reversing the figure and reading the curve of the S against the line around which it is entwined it is possible to find a letter P as well. P and S as well as R and C could suggest a link between the Rosicrucians and the Priory of Sion.

However the watermarks are read, and whatever the strange career of the Bacon brothers may have had to do with secret societies or the treasures of Rennes-le-Château, there can be little doubt that Ben Jonson summed up Francis in the ode he wrote to celebrate Bacon's sixtieth birthday:

Hail! happy genius of this ancient Pile!

How comes it all things so about thee smile?

The fire! the wine! the men! and in the midst

Thou standst as if some mystery thou didst…

January 22nd 1621

The question remains: what was the mystery?

The Shepherd Monument at Shugborough

Shugborough Hall in Staffordshire, ancestral home of the Ansons, is another spotto which the Rennes codes may have extended. In the grounds is a curious structure called “The Shepherd Monument”. It is a bas-relief of Poussin's “Shepherds of Arcadia” but strangely re-arranged. The actual tomb resembles the ornately elaborate one in the Chatsworth version: but the figures are all from the Louvre picture and they stand in a mirror image relationship to their positions in that canvas, with the line of reflectional symmetry below their feet. The Atbash cipher, the two chess boards for the knights' tours, and Shugborough's The Shepherd Monument taken in conjunction with the Louvre version of “The Shepherds of Arcadia” all employ this “folding” technique. The two latter examples produce reflectional symmetry as a result.

There is a clue below the carved shepherds of Shugborough. Cut into the stone are the letters:

There are eight letters in a line, with a D and an M below them. All the letters, with the exception of the final V of the upper line, are followed by dots. The exact positioning of the dots, not on the line but at half the height of the letters, may also be significant.

The eight letter arrangement is an immediate reminder of the MORT épée code on the tombstone at Rennes. It is also significant in terms of a chessboard with its eight rows of eight squares. One widely held view is that these letters are simply an abbreviated memorial inscription, commemorating some important event connected with the Ansons. On the face of it, this is highly likely, and if each letter is simply the start of a word in Latin or English, the possibilities for creating a family reminder of this sort are almost endless.

But if, as some researchers believe, a link between Rennes and Shugborough can be established, then the letters on the Shepherd Monument may have something important to say. Here is one suggested solution which uses all ten letters and involves the kind of geometrical arrangement which appealed to the code makers of the mid-eighteenth century. It is also the shape of the ancient “thorn” letter (p) found in the English alphabet until a few centuries ago, and still in use in Icelandic:

The literal meanings of the words so created are DOMUS, “house”; OVO, “I rejoice”; OVA, “eggs” (the symbols of eternal life, e.g. the old custom of celebrating resurrection with easter eggs); UVA, “grapes”. Suppose that the house refers to Shugborough or to one of the curious buildings in the grounds such as the Chinese House. The idea of rejoicing may be to celebrate the sailor's safe return, the discovery of his treasure or something even more valuable. Anson's wife or brother may have felt that their Admiral's series of miraculous escapes from storms, enemies and tropical diseases warranted a permanent memorial. The Poussin-style tomb may have suggested to them an incredible escape from the mouth of the grave.

The eggs, symbols of resurrection and eternal life, follow immediately after the rejoicing; they are in fact connected to it in the diagram of letters. Because an egg is enclosed, it is also an ancient symbol of mystery, of hidden things, of the unseen. The rejoicing which links the house to this strange old nature symbol could be a rejoicing over something which is unseen but known to exist. Did the Admiral hide some of his Spanish gold as an insurance against future eventualities, and does the monument tell where? Perhaps DOMUS is not Shugborough but Moor Park in Hertfordshire, which is now a golf course, for Moor Park was once the Admiral's home.

The fourth and last word UVA is the most significant one. Nicolas Poussin painted a picture entitled “L'Automne, ou la grappe de la terre promise” as part of his series on the four seasons which he completed between 1660 and 1664. This canvas shows two men in the central foreground with a staff across their shoulders. From the staff hangs an enormous bunch of grapes; each grape is the size of an apple (or, perhaps, an egg?) and the grapes are dark blue. (The tombstone code at Rennes referred to “blue apples”.) Above the grapes in the painting rises a background mountain peak. It could be the peak of Cardou near Rennes, or even the small mountain on which Rennes stands. There are other ancient buildings and fortifications to the left and right of the central figures, and a river runs behind them. Scenery like this could very easily be fitted into the Aude district of southern France or the northeastern slopes of the Pyrenees.

The grapes may have yet another bearing on the mystery. Mrs. Henry Pott suggests in Francis Bacon and his Secret Society that the various grape watermarks used in Sir Philip Sidney's book Arcadia are codes, known only to members of that society. The Latin UVA (“grapes”) on the Shepherd Monument at Shugborough may be confirmation of the connections joining Bacon, Sidney, the first William Anson and the society if, indeed, it exists.

The alternative title of Poussin's picture, “or the grapes of the promised land”, leads to an interesting Old Testament reference from Numbers 13. In this story Moses is commanded by God to send spies into Canaan, to bring back reports about the land and its inhabitants. Moses selects a representative prince from each of the twelve traditional tribes of Israel, and they undertake the reconnaissance. They reach Eschcol (the name actually means “a bunch” or a “cluster”), and cut down one branch laden with grapes, so large and heavy that it needs two men to carry it. The spies return with this and other samples to Moses and make their report. Only Caleb, Prince of Judah, is in favour of attacking. The other eleven princes counsel caution because of the great number and vast size of the indigenous population, some of whom they called Nephilim, or giants.

During the Crusades there was a Templar stronghold at Eschcol. Some of the treasure from that stronghold could have found its way back to Rennes. The original giant grapes of Eschcol could be the mysterious “blue apples” of the tombstone code. Those grapes of Eschcol may have been the same secret, symbolic grapes as the grapes on the watermarks of Sir Philip Sidney's Arcadia and another curious seventeenth century publication called Twenty-Seven Songs of Sion. The 1652 edition of George Herbert's A Priest of the Temple also contains the grape watermarks. The titles of these works certainly suggest a connection: Arcadia, Sion, the Temple.

Boudet's Book(s)

One last mystery before we leave the subject of codes and ciphers: Henri Boudet's grave at Axat. If Boudet left any clues to the Rennes treasures they are cunningly concealed in his strange book La Vraie Langue Celtique. What could well be intended to be a representation of this book is carved on his gravestone. On its “front cover” is the inscription:-

Boudet tomb inscription

Turning the letters over and around — or taking a mirror image of them — gives:-

Mirror-image of the Boudet tomb inscription

Does that mean pages 310 and 311 of the original 1886 edition of his book? Or is the stone “book” meant to represent a Priest's Bible or New Testament? In which case the apparently curious inscription would simply be the early Christian

ICHTHUS

a fish, from which is derived, in Greek, the acrostic: “Jesus Christ, Son of God and Saviour”.

1Our friend Paul Townsend has suggested another interpretation of the 3,4,5 dice. Observing that dice are cubes, he has pointed out that just as:

32+42=52

(the simplest case of Pythagoras' Theorem in integers), so:

33+43+53=63

In contrast to the infinity of integral solutions to Pythagoras’ Theorem using squares, this is the only case of consecutive cubes adding to give another cube. Interpreting 63 as 6x6x6, we seem to have the (in)famous Number of the Beast.