1. Beginning A Practice Session: Whole Body Vibration

Vibration practices are related to paidagong, working in a similar way and with a similar rationale. They are used to break down small or large regions of energetic obstruction, that is, qi stagnation, where qi has become condensed and unusable by the body, and which frequently becomes pathogenic, the root cause of most pain and many diseases. This is accomplished by introducing a different waveform, another frequency of energy from the vibration (or the tap of paidagong) created by a physical movement and guided by the mind into the regions of condensed qi.

In pockets of qi stagnation, energy and fluids no longer move or are restricted and move minimally. Some of the more obvious causative factors include trauma and illness. Even when the trauma heals and the illness resolves, there may be lingering smaller areas where stagnation remains, largely unnoticed. A few other less obvious factors include prolonged inactivity, including sedentary work that is not balanced with adequate exercise; certain emotional states, especially if prolonged; worry and obsessive thinking; certain environmental factors, primarily cold and damp; improper diet; and the side effects of some prescription and recreational drugs. All of these can cause qi to constrict and stagnate, quietly accumulating, contributing to assorted imbalances, until a “critical mass” of sorts is reached, which is when physical symptoms manifest, and then a more rapid degeneration may begin.

Stagnant qi becomes dead, incapable of nourishing life, gradually leaching the life and vitality from surrounding healthy tissue. Conventional exercise, while beneficial in many ways, is often not enough to reverse this process. Exercise will make a person feel better for a time because it causes more qi and blood to move through the healthy parts of the body, but it is not designed to access and dissolve the unhealthy accumulations. If it did, professional athletes would be among the most long-lived members of our culture, but in fact their life span, on average, is shorter than that of the general population. Most professional sports involve impact, the very type of trauma or microtrauma that creates qi stagnation. The incapacitating and sometimes lethal martial art dim mak makes use of this phenomenon.

The whole body vibration you will learn here works well and is very easy to do. It can be practiced by itself at any time of the day, for brief periods of time or as long as you’d like. One of my teachers, a lineage holder from Emei mountain, told me that the Daoist monks from Emei say, “One thousand vibrations a day cures one hundred diseases.” At about three vibrations a second, you can easily do one thousand vibrations in about six minutes. You can do it while watching TV or listening to music. You can also do this at the beginning of the other self-care exercises. The vibrations shake things loose and free things up, and you can use self-care exercises to reorganize that loose energy in specific healthful ways.

Scientific Rationale for Vibration Practices

Whole body vibration benefits the entire body musculature, internal organs, and glands. The rapid firing of muscle spindle cells from whole body vibration causes a neuromuscular response provoking physiological changes within the brain and throughout the body. It is believed that the vibrations may additionally de-imprint the cellular memory of trauma and injury and reimprint positive, healthy information.

The health benefits of vibration acknowledged by Western medical science are varied. In animals, mechanically induced vibration produces a significant reduction in body fat along with increased new bone growth. In humans, bone density is increased, slowing or reversing osteoporosis. Elderly populations experience an improvement in (nonspecific) physical function, equilibrium, vitality, the quality of walking, a reduction in pain, and an improvement in general health. These results are typically achieved using vibration for just four one-minute sessions three times a week for six weeks in total.

Among the general population, some other areas of benefit include athletic and other physical performance, due to whole body vibration’s ability to produce a positive influence on skeletal muscle, applied force, fatigue, oxygen uptake, and balance; a healthful normalization of hormone production and other aspects of metabolic activity; blood circulation; and pain management.

Because animals can’t be trained to practice vibration themselves, and because Western science is more technologically oriented, a vibrating plate was used to mechanically induce vibration to achieve these observable benefits. That also allowed for the vibrations to be standardized and repeatable regarding vibration frequency and intensity, and duration of application. Scientists with differing research agendas and different affiliations around the country and world each had their preferred range of applied frequencies and intensities, and each purported to give the best results. Accordingly, such plates are now commercially available, many producing different frequencies and intensities than their counterparts from other companies, ranging in price between $500 and $10,000! Daoists have been using vibration for thousands of years with no mechanical assistance, and with excellent and comparable results. Appreciate the science, but save your money. And of course, do the following practice.

Method

Stand with your feet parallel, shoulder or hip width apart, arms hanging loosely at your sides. Make sure your knees are slightly bent, not locked. This is your starting position. Now, drop your weight almost as though your were getting ready to spring off a diving board or bounce on a trampoline, lowering your butt just a couple of inches at most. It’s okay if your knees move forward some, but it should be fairly minimal, not like you’re doing knee bends. Feel for your body’s natural springiness, and allow that to bounce you back up to your starting position. It may take a few times for you to feel that springy bounce-back. Once you have it, however, it becomes very easy, and you simply bounce while standing in place. No part of your feet should leave the ground. Establish a comfortable rhythm. If you want to do three vibrations a second, you can count like you might have done as a child to gauge the passage of seconds, “1-Missis-sippi, 2-Missis-sippi, 3-Missis-sippi,” and so on, bouncing with each grouping of syllables. On days when this might be your only practice, go for 1,000 vibrations (bounces), or about six minutes of bouncing. If three bounces a second is too fast for you, adjust accordingly and bounce for a correspondingly longer time.

While you bounce, strive to allow every part of your body to be loose and relaxed. Your arms may swing a little, your torso may sway a bit, and your head may bob forward and back or side to side. All of this should only happen naturally from the bounce; do not try to make it happen. Your shoulders should bounce only from the upward wave generated by the springiness in your body. If you can keep your jaw relaxed, your teeth will chatter with each bounce. You should not force or induce any part of your body to move, aside from how the bounce makes your body move. Any force or intentional movement will generate some amount of muscle tension. If you hold your arms in any position besides keeping them loose at your sides, you use muscles to make that happen. Here, you want to release muscle tension throughout your entire body.

Use your mind to take inventory of your body as you bounce, and see what body parts or regions are not moving, or not moving well. You may notice tension in your low back or your eyes. As you become more sensitive, you may notice that your liver or your kidneys are not moving. You can use your mind to guide the energy of the wave through those regions, to loosen them and allow them to vibrate with the bounce. Ultimately, that’s how you want to do it, but if you initially find it difficult to do that with your mind alone, you can try a few other physical things to help. Make the intensity of the vibration stronger. That is, lower yourself just a little more so your bounce back becomes more powerful, creating a stronger vibrational wave through your entire body. See if you are favoring one leg over the other, and first try to make sure your legs are bouncing equally. Conversely, it’s possible you may need to favor one side more than the other. If you notice that your liver isn’t moving well, for example, you may need to drop more weight down your right leg so the corresponding energetic wave rises more strongly on your right side.

There are many possible variations to this practice. A teacher might instruct you to hold your arms in a particular position to achieve a specific result—there are reasons to purposely block energy flow to a body part, or to shunt more energy to a body part. You might be instructed to chant specific syllables to create another level of vibration using sound to target a particular organ sensitive to that vibration. For general purposes and overall good health, the above practice covers a lot of territory and is the best option.

2. Waking the Qi: Dragon Playing with a Pearl

This is the only exercise in this book to specifically sensitize you to feeling qi. As such, it can serve as a simple entry point to true qigong practices, and can be used to enhance the benefits of the other exercises as you become more adept with it. “Holding a qi ball” is frequently taught to Chinese children as a game, inspiring one of its more fanciful names, Dragon Playing with a Pearl.

At first glance, this may seem like an exercise for the hands and arms, but awakening the qi influences the whole body, moving qi from head to toe and even outside of your physical body. It does not add to the total qi your body has, but you may feel energized from this practice; it can free up qi that has been bound up, previously unusable by you. This can also engender a feeling of peace and tranquility, and can minimize or eliminate pain, especially if caused by qi stagnation or obstruction.

Your qi may be first felt most easily outside the body, usually between the hands. The most sensitive spot to feel qi is located in the center of each palm, and is called laogong, the eighth point on the Pericardium meridian used in acupuncture. Laogong translates as “labor palace,” which according to Arnie Lade in his book Images and Functions, suggests “the point’s possible role in physical, mental, and spiritual revitalization.” Laogong is such a sensitive point that most people will feel some sensation there almost immediately once they’ve focused on it, a great way to allow even a skeptic the chance to feel the presence of qi.

Method

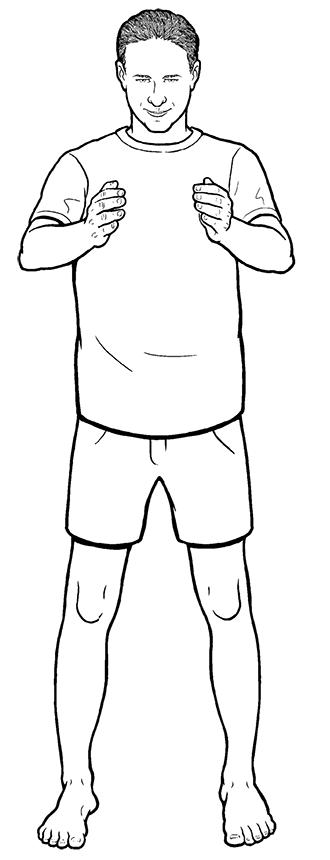

Stand with your feet parallel, shoulder to hip width apart. Your knees should have a slight bend in them, straight but not locked. Keep your spine straight but not rigid, with your chin tucked to straighten your neck, and the tip of your tongue touching the roof of your mouth, just behind your teeth. Keep your breath full, even, and regular throughout the practice. Rub your palms together until they are comfortably warm, and raise your arms to the height of your chest. The arms are rounded wide in front of the body, as though hugging a large tree, which helps to open all the meridian pathways within your arms and between your arms and chest. Move the palms close to each other, facing each other as though holding a tennis ball, or a slightly larger ball, between them (Fig 11.1). Your eyes should remain open and softly focused at a central point between the palms. This is because, although qi may first be easiest felt inside the body if the eyes are closed, here you are trying to feel qi being projected outside of the body between your hands. Wherever the visual attention is placed, the mind is inclined to follow. As the mind is made to focus between the hands, you will become increasingly aware of the initially subtle sensations that accompany the presence of the qi. The mind directs the qi.

Qi sensations are many and varied, can change from time to time in any one person, and may even be unique to a particular individual. Some of the most common descriptions include the sensation of magnetic attraction or repulsion, a feeling of gentle or rushing wind or water, a mildly electric buzz or tingle, or a shift in temperature (either warmer or cooler). Sometimes there may be a definable kinesthetic sensation as much as a mood shift, an emotional shift, or a feeling of being high, in a pleasantly altered state of consciousness. These latter presentations indicate that qi is moving somewhere inside the brain, accessing aspects of the mind. In fact any number of sensations are possible, and none are necessarily wrong. It’s also common for a person to feel different sensations at different practice times. The differing sensations may be due to different levels of sensitivity and accomplishment, the state of health the body is in during the practice session, the quality or quantity of qi being emitted or sensed, the intention of the practitioner, the immediate environment (which influences qi), current emotional state, the way a particular individual is energetically “wired,” or combinations of the above.

Once you are feeling something between your hands, whatever that may be, then you can begin playing with those sensations. Move your hands farther apart, as though the ball is growing larger. Only move your hands as far apart as you can while maintaining that sense of qi between them. If you lose that sense, bring your hands closer together until you regain it. Then move your hands as though you are rolling them over the surface of the large ball, so that your right hand may be on top of the ball with your left on the bottom, and then slowly reverse those positions. You can move your hands any way you can think of, as long as you keep the laogong points facing each other and you maintain the sense of qi between them. Practice this as long as you’d like. When you are ready to finish, either bring your palms closer together slowly, until they physically touch, and then complete the Running the Meridians practice that follows, or place your hands on your Dantian to store qi there, as is described in Qi Storage at the Dantian, after the next exercise.

3. Ending a Practice Session: Running the Meridians

This is another practice that influences almost your entire body at once. It can be practiced alone at any time of day for a quick pick-me-up, or it can be practiced at the end of any series of self-care exercises you choose on any given day. Almost all of the self-care exercises open a small or a large part your body, freeing energy that may be stagnant or restricted in those parts. This exercise organizes the energy that has been freed, and directs it through your acupuncture meridians adding to the normal flow of healthy qi, in the proper direction, to increase energy and benefit overall health.

This exercise makes use of the Chinese anatomical position: when standing, raise your hands over your head, palms facing forward in what looks like a gesture of giving up or surrender. Within the acupuncture meridians, Yang qi runs down the back of your body from your head to your feet, including the backs of your hands and arms, and Yin qi runs up the front of your body from your feet to your head. With your body aligned in anatomical position, all the Yang meridians are facing the back of your body, and all the Yin meridians are facing the front of your body. Keep this image in mind when you perform this exercise, since your body will be in motion and you may not readily see that you are encouraging qi to flow in these healthy directions.

You’ll work the upper half of your body, primarily your arms, separately from the lower half of your body, primarily your legs. It’s most typical to begin this practice with your arms, as I’ll describe here. This is most advantageous when running the meridians at the end of a taiji, qigong, or other self-care practice. When you finish with the legs, your hands naturally wind up at your lower Dantian, the perfect location to facilitate simple qi storage at the end of any set of self-care practice. If you run the meridians as a stand-alone practice at any time, and do not do qi storage afterward, it’s fine to start with your legs and end with your arms if you prefer.

Method

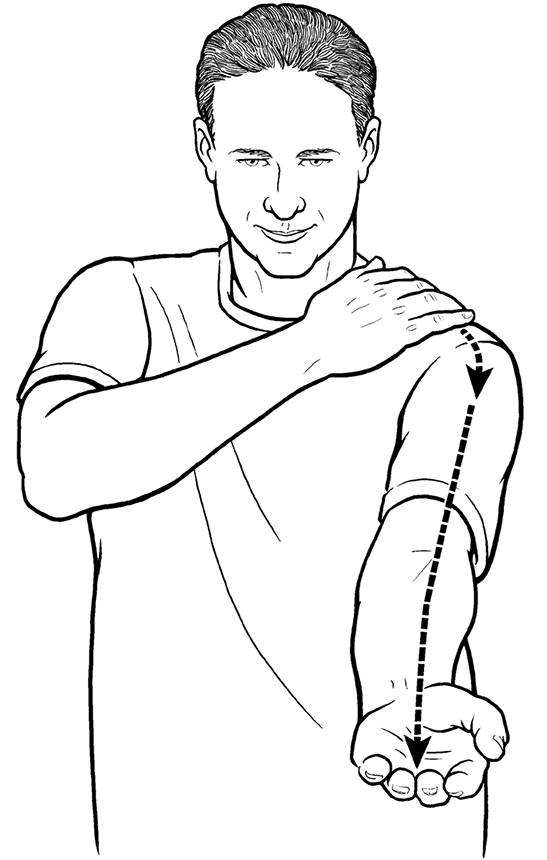

Stand with your feet parallel, shoulder or hip width apart. Make sure your knees are not locked, and slightly bent. As with all exercises where you will use your hands to help direct qi anywhere in your body, it’s a good idea to rub your palms together until they are warm. This brings both blood and qi to your hands. If you have previous qigong experience and you know beyond a shadow of a doubt that you can bring your qi to your hands at will, you can skip that step. Extend your left arm straight in front of you, at approximately shoulder height, palm facing upward. Place your right hand, palm down, upon your left shoulder where your neck and shoulder meet (Fig 11.2A on next page ). Rub or wipe your right hand down the entire length of your left arm, to just beyond your left fingertips. Then turn your left hand palm down, and rub or wipe your right hand up the back of the entire length of your left arm (Fig 11.2B on next page ), from backs of the fingertips to where your neck and shoulder meet. At this point, remove your right hand, and extend your right arm directly in front of you at approximately shoulder height, palm facing upward. Do your best to make the movement of your right arm smooth and flowing, with a sense of purpose and connection rather than randomly moving it into position.

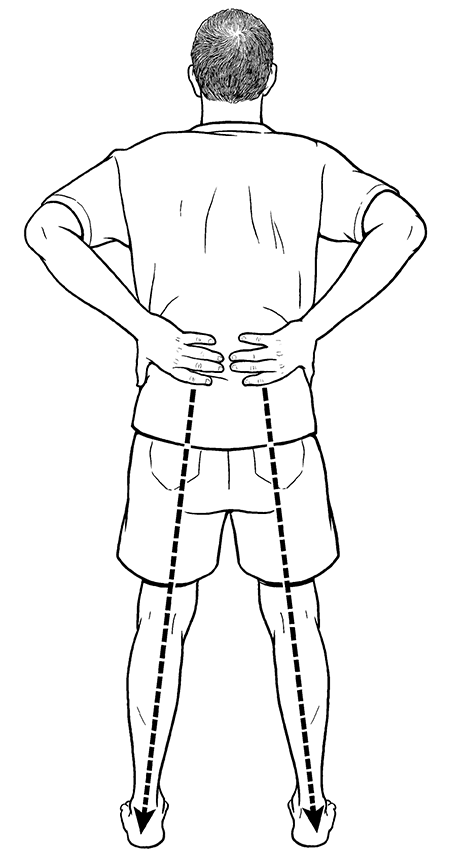

Figures 11.2A and 11.2B (Ending a Practice Session: Running the Meridians)

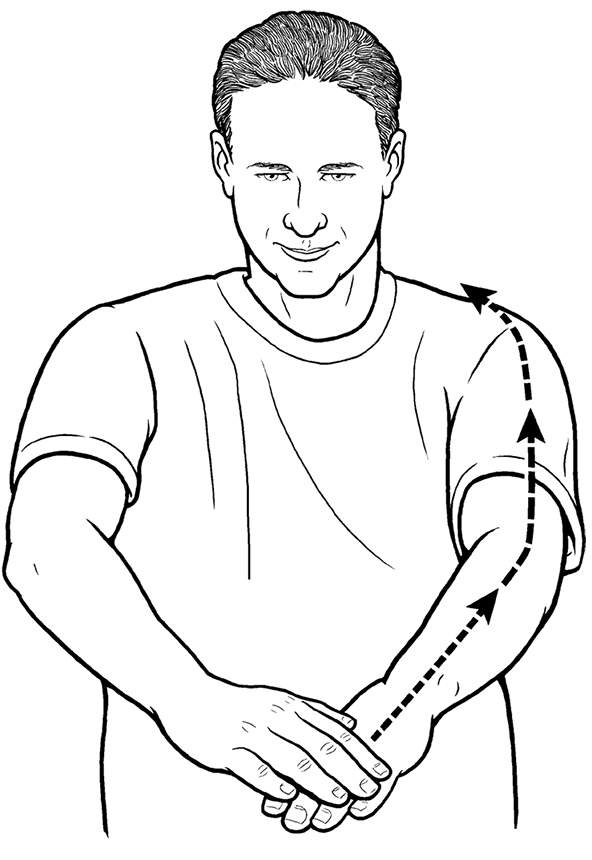

Now place your left hand, palm down, upon your right shoulder where your neck and shoulder meet. Rub your left hand down the entire length of your right arm, to just beyond your right fingertips. Then turn your right hand palm down, and rub your left hand up the back of the entire length of your right arm, from backs of the fingertips to where your neck and shoulder meet. At this point, remove your left hand, and extend your left arm directly in front of you at approximately shoulder height as before, palm facing upward. Do your best to make the movement of your left arm smooth and flowing, with a sense of purpose and connection rather than randomly moving it into position. Repeat this procedure twelve times.

Even though your arms are extended in front of you and in motion, remember that in Chinese anatomical position, your are wiping your arms in the same direction as qi naturally flows within the meridians; that is, up the front or inner Yin surface of your arms, and down the back or outer Yang surface of your arms. As you get more familiar with this practice, you can perform it at either a slower or a faster pace. The smoothness of your movements and the regularity of the rhythm you establish is more important than the speed itself.

Figure 11.3B (Ending a Practice Session: Running the Meridians)

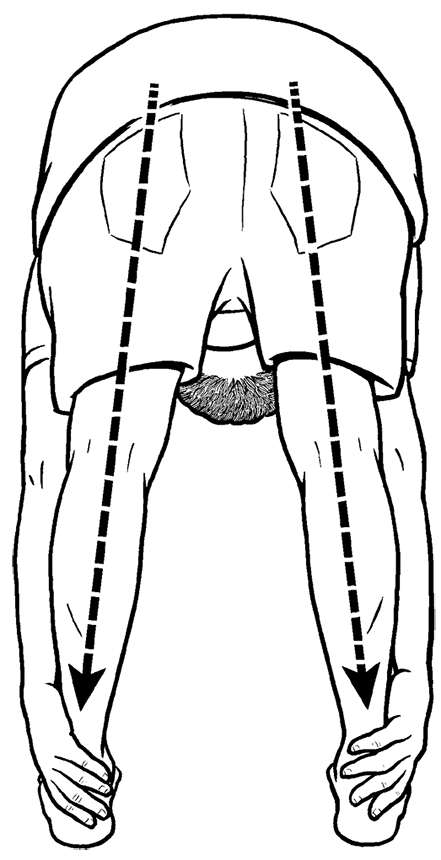

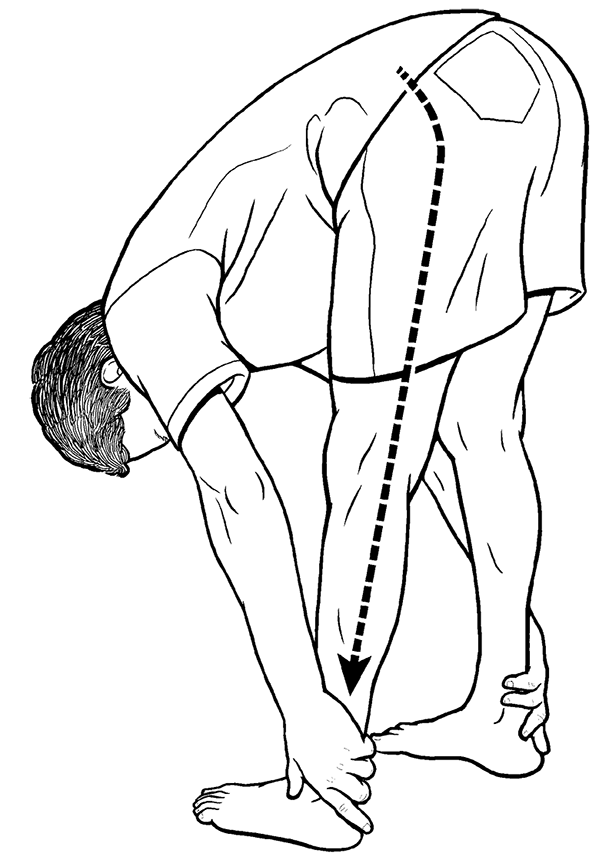

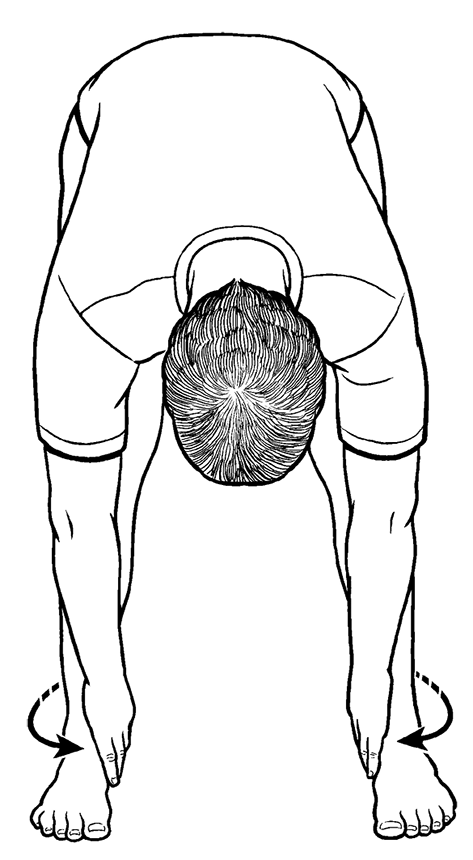

Place the palms of both of your hands on the small of your back, just above your buttocks, so that the tips of your middle fingers are nearly touching (Fig 11.3A on previous page ). Bending forward, keep both hands in contact with your body and wipe down your buttocks and the backs of each leg, right hand wiping down the right leg and left hand wiping down the left leg. Wipe behind each knee, and all the way down to your heels. Make sure to spread your thumbs from the rest of your hands, and use them to wipe down the outer, lateral surface of your thighs and lower legs (Fig 11.3B).

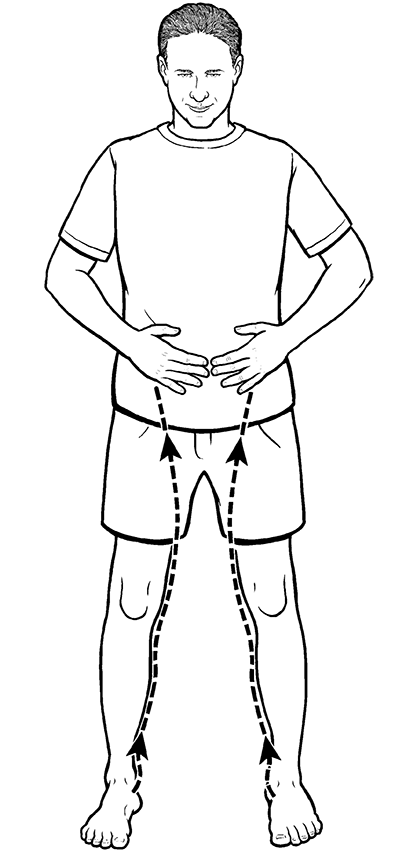

Figure 11.3C (Ending a Practice Session: Running the Meridians)

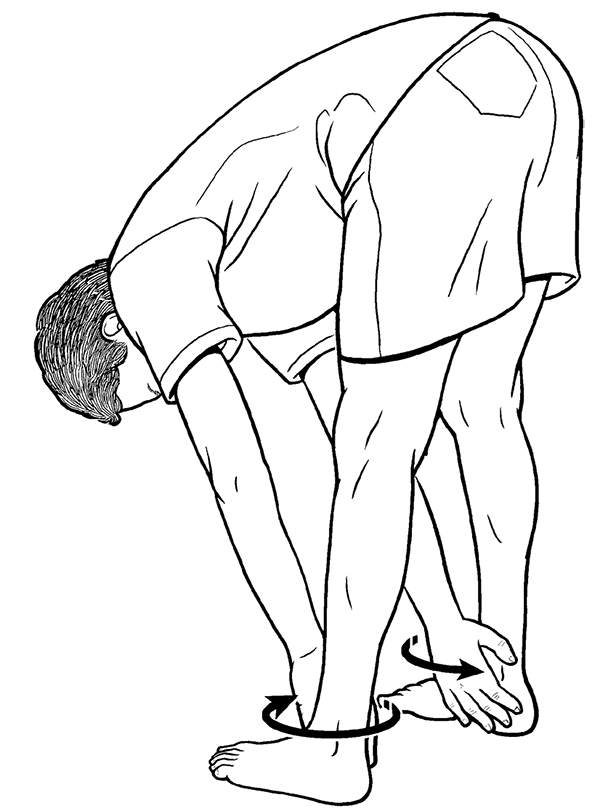

Keeping your hands in contact with your body, wipe around the outer ankles, over the tops of the front of the feet, and then to the inner ankles (Fig 11.3C ). Rising up, wipe the inner surface of your lower legs and thighs. As your hands near your torso, spread them slightly so they move just outside of your genitals, and bring them to your low belly just above your pubic bone and below your navel (Fig 11.3D on next page ). Still maintaining contact with your body, spread your hands away from each other, wiping around your waist until they arrive at their starting position at the small of your back, middle fingers nearly touching. Repeat this procedure twelve times.

The Dantian is one of the main energy centers in the body. Although there are three primary Dantians—upper, middle, and lower—when the word Dantian is used alone without any stipulation, it’s almost always the lower Dantian being referred to. That’s because the lower Dantian has the most to do with physical functions, health, and vitality, so it has most to do with everyday life and with the interests of the majority of people involved in energy practices. It also serves as the main reservoir of the energy acquired through various qi practices, so learning to store qi at the Dantian is the main, if not only, way to have a net gain of energy at the end of the day.

If you practice taiji or qigong, you may have generated more qi or drawn healthy qi in from your environment. If you’ve practiced a self-care exercise set, you have freed up some previously unusable qi within your body. In either case, it’s a good idea to store what is now a surplus of qi, so that it does not simply dissipate over the course of the day. There are many ways to store qi. This is one of the simplest, and is best done after Running the Meridians or Dragon Playing with a Pearl.

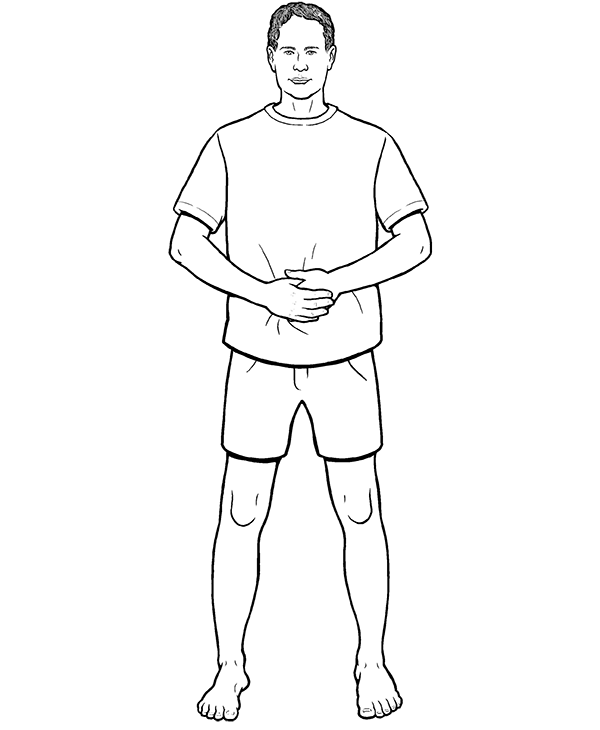

After the twelfth repetition of running the leg meridians, your hands naturally arrive at your lower belly, where your Dantian is located. This time, do not slide your hands around your waist to the small of your back, but leave them at your low belly, just below your navel. Men should place their left hand directly on their belly and cover it with their right hand (Fig 11.4 on next page ), while women should place their right hand directly on their belly and cover it with their left hand. This is because in men, the right hand is the more Yang hand, and in women the left hand is the more Yang hand. Yang is naturally protective and stays more to the surface relative to Yin, and Yin is nurturing and stays more interior relative to Yang. This hand placement simply follows the natural order of Yin and Yang.

After running the meridians, your hands should still feel slightly warm. You can use that warmth as a tactile reference. With your hands placed just below your navel, allow the warmth to penetrate your low belly, all the way to your Dantian, two to three inches in from the surface of your body. For most people, it will be easiest to close the eyes to avoid any external distraction, and use the mind to feel for that warmth at the Dantian. If you don’t feel the warmth, that’s okay, because the warmth is not the qi itself; it’s just a guide to help you feel it. Allow your mind to settle on that location as best you can. You may experience any of a variety of other sensations there: motion like wind or water, tingling, tickling, or a sense of light or expansiveness. Again, you may feel none of those things and that’s okay too. If you do feel something there, simply keep your mind on it until it quiets and stops. Whether you feel anything specific or not, if you keep your mind on your Dantian, qi will be stored there. At some point you will feel a sense of peace, stillness, or completion, and then you’ve finished storing what qi you can for the day. It may take just a few seconds or a few minutes. When you feel you are through, lower your hands to your sides, open your eyes, and move on to whatever is next in your day.

5. Follow Your Breath Meditation

Every previous practice in this book has directly addressed some aspect of the physical body. Some of those have enlisted the mind toward that end. This meditation practice is included now specifically to benefit the mind. Since every physical process is under the direct regulation of the mind and the organ it is most obviously associated with, the brain, the entire body will benefit from meditation practice.

The brain is the central processing unit of the nervous system, relying on, controlling, and responsible for all the electrical activity in the body. When the brain and nervous system are overdriven, stress is the inevitable result, setting the stage for all the diseases caused by stress, and most of the chronic aches and pains anywhere in the body. When the brain is quieted, mediated by the mind, that electrical activity diminishes, tension discharges, stress drops away, and the stress-induced disease processes and pain can be halted and reversed. The mind also plays a role in emotional responses and experiences, and emotions influence and are influenced by neurotransmitters and other hormones. It is well known to Chinese medicine that lingering emotional states always affect health (usually adversely), and conversely, imbalances in the function of each organ and organ system create a unique emotional proclivity. A calm, balanced, quiet mind reduces and ultimately eliminates emotional upset. The external circumstances may not change, but your response to those circumstances can and will change. This is how the hormonal systems can benefit and not become overtaxed, and another way the nervous system is benefited.

There are many types of meditation. Most are intended to turn off the conventional thinking processes, quiet the mind, and create an inner stillness that allows for a nonintellectual awareness, a sense of simply being, and the perception of a connection with everything in existence. The sense of just being, existing in the moment, removes any worry and anxiety stemming from concerns about the future and regrets of the past. The perception of connection with all things in existence gives a sense of belonging, acceptance, grounding, and certainty about one’s place in the world.

There may be no other time in history when meditation practice has been more necessary than it is today. With so many people completely “plugged in” to modern technology—with cell phones, texting, instant messaging, constantly working or playing on a laptop or iPad, updating Facebook status, Tweeting, having both jobs and families that demand you are electronically if not physically accessible twenty-four hours a day, and streaming audio and video news and entertainment to a computer or TV much of the rest of the time—everyone is perpetually distracted outside of themselves, seldom given the opportunity to catch their breath and learn more about who they really are, away from all those distractions. Paradoxically, most people also consider these contemporary distractions to be “normal life,” and the thought of being without them may seem both impossible and boring. In fact, the perception of boredom has always been one of the biggest obstacles people have faced when beginning a meditation practice, and even when beginning some of the slower-moving or stationary practices of qigong, taiji, and gongfu. If you are one of those people, this may interest you and help you overcome your reservations.

Even outside of the context of meditation, new scientific research has demonstrated that enforced boredom—being made to do a mindlessly repetitive task—and relaxed boredom—daydreaming—serve a creatively useful purpose. In his book Boredom: A Lively History (Yale Press), University of Calgary professor Peter Toohey, PhD, cites studies at the University of British Columbia which showed that in volunteer students given mindless, routine assignments while having their brains scanned using functional magnetic resonance imaging, there was a high amount of activity in the part of the brain associated with complex problem solving. This indicates that when your mind is free of external distractions, it can work on puzzles, problems, and more abstract concepts, helping you find solutions that might otherwise elude your conscious thought processes. This has long been acknowledged as one of the side benefits of meditation, and is a likely mechanism to explain some aspects of inspiration and creative thought.

This entry-level meditation is very simple, yet very effective. Some variation of this practice is used in almost every spiritual and secular meditation tradition throughout the world.

Method

Sit on a hard or firmly cushioned chair, nothing too soft, at a height that allows your knees to be bent at about a 90-degree angle. As long as your back is not in pain and in need of support, sit on the forward third of the seat. Do not lean back on the chair back, and do not slouch. Sit erect and upright, but without strain or force. Even though you are seated, keep your feet parallel at about shoulder width apart with your knees aligned directly above your feet. You can place your hands on your knees, or fold them in your lap. If you are not already an experienced meditator, hands placed on your knees will extend your arms and help to keep your armpits open, allowing for a freer flow of qi between your arms and torso. Place the tip of your tongue at the roof of your mouth, just behind where your teeth meet your gums. This connects two major energy pathways in the body, the Du meridian running up your back, over your head and ending at the roof of your mouth, and the Ren meridian running up the centerline of the front of your body and ending at the tip of your tongue. This posture will keep your body most open, create energetic connections, and allow for qi to move freely with minimal physical obstructions while you meditate.

Next, pay attention to your breathing. Breathe in and out only through your nose, unless you have a nasal obstruction that makes that impossible. Your breath should be comfortably long, and will likely get longer as you practice over time. Your breath should also be silent and slow, not coarse, noisy, or rough. Most people have a natural stopping point at the end of their inhalation and exhalation, where they have a pause, a brief period of held breath. Try to keep your breath continuous, so there is no pause between inhalation and exhalation. That creates a sense of circularity in your breathing rhythm. Still sitting erect, keep your belly soft and relaxed. Do your best to keep your chest still and sunken, so that it does not rise or expand forward when you inhale, nor drop when you exhale. With your mind, feel the region between your lowest ribs and your pelvis. On your inhalation, direct your breath to that region, and let it expand in all directions, including toward your back, like a balloon filling with air. On your exhalation, allow everything in that region to retract toward the center of your body, as though air was being released from the balloon. Practice this for a few minutes, with your eyes open or closed; either is fine. Most people find that closed eyes help remove external distractions and facilitate sensitivity to inner processes. The better you are able to breathe in this way, the more tension will be released from your nervous system, and the more deeply you will relax when you meditate.

The final piece of this practice begins the actual meditation. It’s called “following your breath” because that’s exactly what you’re going to do, in one of three ways. Each way gets slightly more challenging and takes you a little further, but all yield good results. In the first way, each time you inhale, silently say to yourself, “inhale,” and each time you exhale, silently say to yourself, “exhale.” Let that be the only thought in your mind. It’s inevitable that other thoughts will arise, but when you notice them don’t try to force them away; simply bring your attention back to “inhale, exhale.” The second way requires you to extend your focus just a bit farther than “inhale, exhale.” On every exhalation, count the number of your breath, so that on your third exhale for example, you will silently say “three” to yourself, on the seventh exhale, you will say “seven,” and so on up to ten. Then begin counting again from one. Repeat this counting as long as you’d like. The third way is similar to the second, but you do not stop the count at ten and start over; instead, you continue counting each breath in order until you end your meditation. The numbers continue to increase the longer you meditate. Your focus will need to extend farther in this practice, as you will need to keep track of your count throughout the meditation. As with the “inhale, exhale” variation, when extraneous thoughts arise, don’t try to force them away—simply notice and release them, and bring your attention back to your count.

Neither the numbers nor the words “inhale, exhale” have any particular meaning to deepen your meditation. They are not religious or spiritual mantras. They are devices to teach your mind to focus on one thing, or at most two, as some of your attention will be on your proper breath. Anything that narrows the focus of your mind frees it from being distracted by the part of your mind that generates random thoughts. With practice, you’ll come to recognize the distracting parts of your mind even while not meditating, and will become better at quieting them, like a parent calming a crying child. That will allow your mind to sink into deeper parts of itself undisturbed, and along the way to learning more about yourself and your true nature, you’ll enjoy better health by lowering your stress levels and maintaining mental and emotional calm.

At first, don’t tax yourself by trying to meditate too long. If you’ve never meditated, ten minutes is a good length of time to begin with. Don’t get frustrated when your attention wanders or you lose your count. That will happen, and it happens with everyone. It happens less often the more your practice. You may soon find that ten minutes seems too restrictive, and that’s when you should extend your meditation for longer periods. Once you get familiar with and acquire a taste for meditation, a half hour or more will pass very quickly.

Standing practices have been the cornerstone of qi cultivation in many systems of qigong and gongfu (power-building practices used most typically for martial arts purposes, and in some advanced spiritual trainings) for thousands of years. I almost did not include standing in this book, since this practice is best learned as a complete qigong under the guidance of an experienced teacher. Recently, however, the virtues of standing as opposed to sitting, and of standing barefoot on the ground, have caught the attention of Western medical science, and researchers have found an interesting and revealing variety of health benefits from common everyday standing. So it seems like an introduction to this practice is in order, to give you a different perspective on a practice you might encounter in popular media elsewhere. After taking a look at some Western findings, you’ll be given instruction in a basic standing practice commonly used as a preparation for Standing qigong. The practice requires a mindfulness and a specific full-body awareness beyond what the Western researchers studied, and so provides greater health benefits than those of ordinary standing.

Western medical science has determined that people who sit for more than four hours a day have an increased risk of death from natural causes, arising from an increase in obesity and metabolic syndrome (a complex of conditions including high blood pressure, high blood sugar, high cholesterol, and excess body fat around the waist, usually accompanied by fatigue), and includes cardiovascular disease and cancer. That risk increases the more hours per day that a person typically sits. This corroborates the ancient Chinese medical observation that excess sitting damages the Spleen and Stomach, organs associated with absorption and metabolism of nutrients, energy production, proper muscle functionality and strength, and along with other organs is involved in blood production. A poorly functioning Spleen will create Damp in the body, a pathogenic influence frequently involved with various tumor formations and many types of cancer, along with numerous other less serious conditions. Considering that, even common unstructured standing a few times throughout the day is a simple and useful strategy to improve health and longevity.

Evolving Western biosciences have begun examining “earthing” or grounding, the practice of standing preferably barefoot on the ground. These explorations have provided numerous scientific findings related to that simple practice, and many healthful physiologic changes have been demonstrated.

From a Western perspective, energy is usually associated with measurable quantities, such as electrons and ions. Because the skin is a very good electrical conductor, electrons and ions are relatively freely able to pass through it. Remember that the earth is a giant magnet, with a north and south pole, and it generates a lot of free electrons. When walking or standing barefoot on the ground, those electrons are transferred into your body through the soles of your feet. Kidney 1, the acupuncture point called the Bubbling Well point located at the ball of the foot and introduced earlier in this book, is known to be an especially strong conductor of earth energy, and is responsible for all the rising currents of qi within the body.

Free electrons provide many benefits. Foremost, they are very powerful antioxidants and are capable of producing healthful changes in heart rate and reducing inflammation. Decreasing inflammation most obviously reduces inflammatory pain, but inflammation also plays a role in almost every debilitating degenerative disease, including diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. Another factor in heart health, grounding rapidly increases zeta potential, a type of charge around red blood cells that causes the blood to thin, improving circulation and lowering blood pressure. It also reduces the red blood cells’ tendency to clump together, so clots are less likely to form and existing clots may be broken down.

The antioxidant properties of free electrons make them able to quench, or neutralize, excess free radicals. This increases longevity, since free radicals can accelerate aging by causing genetic damage and mutation, damage the energy-producing mitochondria found in every cell, and reduce the efficiency of enzymes, which themselves are both antioxidants and regulators of virtually every biochemical process in the body. This includes the biochemical reactions necessary for all types of healing. Enzyme therapies are sometimes used by practitioners of naturopathic and orthomolecular medicine for that purpose.

Plastic or rubber-soled shoes act as insulators and cut off the flow of free electrons into the feet. This may cause, or at least contribute to, the many diseases of modern life. Free electrons are not the totality of healthy qi, but these findings support what qigong masters have said for millennia: “A wise man breathes through his feet.”

You can take advantage of these findings by simply standing more throughout the day, walking barefoot on the earth as much as possible, and if necessary changing your footwear to natural materials that more readily transfer electrons. If you want to maximize those benefits, and add many more beyond the basics of earthing, the following Standing practice will be very rewarding.

Figures 11.5B and 11.5C (Standing Practice)

Method

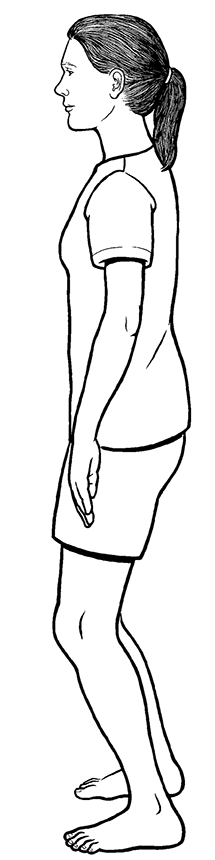

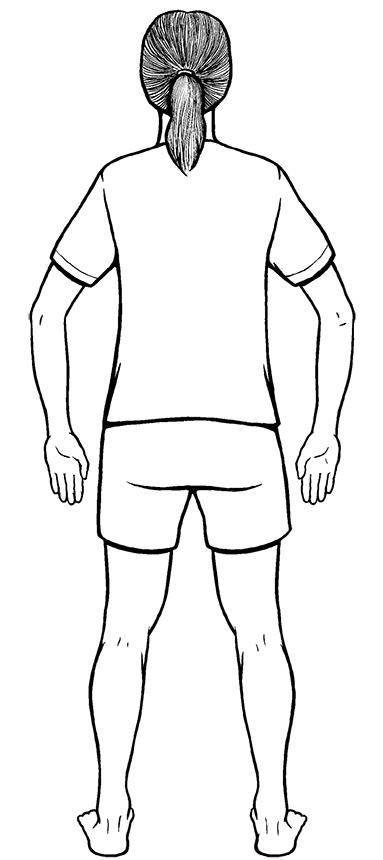

This most basic Standing posture (Zhan Zhuang, “Standing Like a Stake” or “Pole Standing”) is a foundational practice found in most schools of qigong with minor variations, used in the early stages of qi cultivation as preparation for complete Standing qigong practices. Here the body is regulated even when standing still, when there is very little going on externally that is observable to an untrained eye. It is sometimes referred to as Standing Meditation, but most practitioners simply refer to this as “Standing Practice” or just “Standing” (Fig 11.5A–Fig 11.5C on previous pages).

Here are the basic alignments and regulations. Keep in mind, for any one alignment to be fully accomplished, all must eventually be adhered to simultaneously. This may take some time, even in this early stage of practice. We’ll begin at the feet, the body’s foundation, and work our way up from there.

- Standing upright, place your feet parallel, at shoulder width apart.

- The weight of the entire body should be spread evenly across the sole of each foot, with no emphasis placed toward either the ball of the foot or the heel. Do not let your ankles collapse inward or outward.

- Bend your knees slightly, keeping them relatively straight but not locked. Even with the knees slightly bent, try to maintain a sense of lift at the back of your knees, so that the whole joint space feels open.

- The knees should bear no weight at all, but rather transfer the weight of the upper body to and through the feet.

- The perineum is kept open, most simply by making sure your knees are not collapsed inward toward a knock-kneed position.

- Point your sacrum straight down to the ground, causing the curvature of the low back to become more flattened. Do this by relaxation and release of any tension in your low back, and not by tightening or tensing the belly.

- Create a slight bend or fold at the inguinal groove. When coupled with the sacrum pointing toward the ground, this has been likened to the sensation

of being just about to sit on a stool. That sensation may help give you the correct feeling for this part of the posture, but it can cause a tendency to stick the rear out some. Care must be taken to avoid that, as it will increase the curve in the low back, counter to the above instruction. - Raise your midriff, by increasing the distance between the iliac crest at the sides of the pelvis and the lowest ribs. This will help you to additionally flatten your lower back.

- Spread your shoulder blades comfortably away from the spine so that the palms of each hand can easily face rearward, with your thumbs lightly touching the sides of your upper thighs. In a common variation, palms face the sides of the thighs, but the shoulder blades are still spread from the spine.

- Your head should lift toward the ceiling with a sense of being drawn upward either magnetically or as if lightly pulled by a string, helping to reduce the curvature of the mid and upper spine while creating a sense of openness and separation between the top vertebra and the base of the skull. So, the lower spine should feel like it’s dropping as if to sit, while the mid and upper spine have a sense of rising.

- Keep your jaw parallel to the ground while tucking your chin, drawing it rearward to further lessen the curve of the neck while increasing the gap between the occiput and atlas (first cervical vertebra).

- Place the tip of the tongue on the roof of your mouth, on the hard palate directly behind your upper teeth.

- As much as the mid and upper spine are rising, your chest should feel a commensurate dropping or sinking, without a sense of collapse. The sinking of the chest combined with the spread of the shoulder blades should produce a sense of a hollow or depression forming just toward the midline of the body from the front of the shoulders, as well as an openness in the armpits.

- Keep your belly soft, and your whole body relaxed.

Every aspect of this posture creates openness while in stillness, reducing any physical obstruction to qi flow, so that whatever amount of qi you have available to you at any time will be able to move through you as freely as possible. If you stand barefoot on the ground, all the earthing benefits will be increased. Celestial energies are descending at the same time, and this posture will allow you to access those as well. At this stage of practice, you don’t need to think about the earth or celestial energies. Keeping your mind as still as possible will do you the most good.

Similarly, almost every aspect of this posture has a specific purpose in addition to being a part of the synergistic whole. For example, keeping your shoulder blades spread away from your spine releases tension in the muscles between your shoulder blades and allows the vertebrae there to separate slightly. The spinal nerves that exit that part of the spine innervate your heart and lungs, so the separation of those vertebrae removes pressure on the nerves, and your heart and lungs will function better. The back Shu points of the heart and lungs, specific acupuncture points on the Urinary Bladder meridian that influence the function of those organs on a qi level, are also located between the shoulder blades in that region of the back. The softening of that muscle tissue, combined with the slight stimulation from the stretch, encourages more qi flow to the heart and lungs. As an example of synergy, the lengthening of the spine, by pointing your sacrum to the ground while simultaneously lifting your head toward the sky, increases the benefits to your heart and lungs from the spread of your shoulder blades, by increasing the separation of the vertebrae and the flow of qi through the back. Take this as encouragement to incorporate each aspect of the Standing body alignments as precisely as possible.

While you are learning this Standing posture, your mind will necessarily be working to keep track of all the alignments, and to make sure your body stays relaxed while doing so. That’s a normal part of this process. At some point, in maybe weeks or months, it will begin to feel very natural to you, and you’ll find you won’t need to think about it much if at all. You’ll feel when you are out of alignment, and will adjust your posture accordingly. When you get to that point, if you want to increase the benefits of Standing, you can include the Follow Your Breath meditation as part of the practice. This will help to further quiet your mind, and by focusing on your breath, you’ll be bringing in more qi from the air (qing qi), your immediate environment, in addition to earth qi and celestial qi. In this case, some of your awareness must still remain on your physical posture.

Twenty minutes is the recommended minimum amount of time for Standing, and many qigong masters encourage their students to stand for an hour or more. In some schools, a teacher may even demand that hour. I know at least one Chinese master who insisted his students do nothing but that, Standing for one hour a day in class for one year before he would even begin to teach them anything more. It is considered that important a practice. You may find Standing to be unexpectedly taxing, though, and in the early stages, if you can only stand for five or ten minutes, that’s fine. Do your best to increase that amount of time. The benefits will increase exponentially, not additively.

Figure 11.1 (Walking the Qi:

Figure 11.1 (Walking the Qi: Figure 11.3A (Ending a Practice Session: Running the Meridians)

Figure 11.3A (Ending a Practice Session: Running the Meridians) Figure 11.3D (Ending a Practice Session: Running the Meridians)

Figure 11.3D (Ending a Practice Session: Running the Meridians) Figure 11.4 (Qi Storage at the Dantian)

Figure 11.4 (Qi Storage at the Dantian) Figure 11.5A (Standing Practice)

Figure 11.5A (Standing Practice)