4

JUNKIE

When I first got to college, the excitement of my new independence led me to experiment with a new self-image. Before long, I’d settled on a punk-goth look. This involved a beaten-up black motorcycle jacket worn over a sweater with the collar and sleeves torn off, a skirt ripped to mid-thigh, fishnet tights, eight-hole Doc Martens boots, and dirty white lace gloves with the fingers cut off. My hair, crimped to death, was part blonde, part pink. It was 1986, the year of Sid and Nancy, and I was nineteen. My gutter chic was seriously out of place in Oxford’s cloisters and croquet lawns, which was precisely the point. I was secretly flattered when one afternoon, on arriving at an English faculty get-together, I was handed a glass of wine by my tutor, who announced, “I’m sorry, my dear, we don’t have any syringes.”

Although I liked to play Lou Reed’s “Heroin” at high volume, frightening the girls in my dorm, I knew next to nothing about drugs. My friends smoked pot, but whenever I tried it, it made me feel sick and dizzy. I found the taste of alcohol nauseating, although I liked Bulmers cider, which contains five teaspoons of sugar per pint, because it tasted like pop. It was very strong and I’d throw up if I drank more than three pints.

I wanted people to think I was hard and tough, but the punk rock style favored by my friends and I was all naïve bravado. Our leader in matters of taste was my boyfriend Eric. Although he was only three years my senior, Eric was a lifetime ahead in experience. He’d spent his year abroad living above a brothel in Barcelona, and he introduced us to the work of Charles Baudelaire, the Marquis de Sade, and Jean Genet. My friends and I loved to read about criminals, addicts, and thieves. Our touchstone was William S. Burroughs’s Junkie (originally with the subtitle: Confessions of an Unredeemed Drug Addict). We venerated our tattered copy, passing it from hand to hand and appropriating its colorful jargon.

I knew literature didn’t always have to focus on rich people, or even the middle classes—I’d encountered the noble poor in Dickens, George Eliot, and Thomas Hardy, and I’d read about the not-so-noble poor in George Orwell and H. G. Wells—but until then I’d never read literature that involved the kind of people Burroughs writes about in Junkie. Horror was my cup of tea, but I only knew the kind of horror that elevates ordinary nastiness, making it lofty and supernatural. Junkie does just the opposite, grinding your face in the dirt. I chose it for the prisoners to read because I thought they’d be curious about Burroughs’s realistic, unflinching description of the addict’s underworld. For many of them, this was their domain, or it had been at one time, and I was curious whether they’d recognize themselves in its denizens.

APRIL 10, 2013

I handed out copies of Junkie, gave the men some information about Burroughs and his life, and all at once, before we’d even begun to read the book, we were in the middle of a frank discussion about drugs. The book’s author and narrator, Bill Lee—the pseudonym used by Burroughs when the book was first published—claims that, to get addicted, you’ve got to be determined. “It took me almost six months to get my first habit, and then the withdrawal symptoms were mild,” he says. “I think it no exaggeration to say it takes about a year and several hundred injections to make an addict.” The prisoners all disagreed with Burroughs on this point, but they liked the way his claim opposed the dogma of the twelve-step groups popular in prison like Narcotics Anonymous, with their unshakable premises, their uncontestable assertion that all drugs are the same, and you’re either an addict or in recovery.

The men in the group who’d been drug users thought this version of addiction was simple, even infantilizing. In contrast, they were pleased to learn that Burroughs, despite his drug use, lived a long life, continuing to write and paint into his eighties. In his prologue to the 1953 edition of Junkie, Carl Solomon calls Burroughs “an unrepentant drug addict.” He often kicked his habit, sometimes for years at a time, but always knew he’d use again when the time came. The men agreed that you could live your whole life this way—it’s how many of them lived themselves—but in NA the only goal was “complete and continuous abstinence.” There was no place for the “unrepentant.”

One man confessed that his first time using heroin had been the turning point in his life.

“It was like, I don’t know, like finding this . . . this magic thing,” he said, his eyes shining. It was what I’d always been looking for. When I’m on H it’s, like . . . this pure version of myself. It’s who I really am inside.”

“You sound unrepentant,” I observed.

“Damn straight,” he affirmed. “Truth is, long as H exists in the world, I’m gonna use it.”

“Do you miss it?”

“Are you kidding me?” He gave a brief, contemptuous laugh. “You can get anything you want in here. I’ve got so many added years for dirty urine, it’s like a whole ’nother bit.”

Of course, you could get anything in prison. Deprivation creates desire, and desire creates demand. Every so often the men would be required to take urine tests, sometimes in their cells and sometimes in an area near the visiting room. Prisoners called to take these tests were supposedly selected at random by a computer, but the men believed the COs had “snitch lists” or picked out prisoners based on their suspicious behavior, or just for no reason at all. Some of the men, I felt, regarded the Department of Corrections as their adversary in an ongoing game, the object of which was to score as often and in whatever form they could. In this way, their lives gained a kind of meaning from pursuit itself, whether of coffee, cigarettes, or products more illicit and more difficult to obtain. Perhaps this is what Burroughs means when he writes, “Junk is not a kick. It is a way of life.”

Most of the former addicts admitted they’d started to use when they were bored and directionless teenagers looking for anything to give them a new high. According to Burroughs, “You become a narcotics addict because you do not have strong motivations in any other direction.” When asked by an interviewer why he felt compelled to record the experiences he describes in Junkie, Burroughs replied, “I didn’t feel compelled. I had nothing else to do. Writing gave me something to do every day. I don’t feel the results were at all spectacular. Junkie is not much of a book, actually. I knew very little about writing at that time.”

I grew up around people who used drugs, and for me the motivation in the other direction was reading. “Books always absorbed me more than anything else,” I told the men. “Even now I’ll sometimes pour myself a cocktail and settle down with a book. A couple of hours later, when I put the book down and get up to go to bed, I’ll notice the drink still sitting there.”

The men were unconvinced.

“I got to say, I read a few books, and I can’t imagine any being that good,” said Kevin.

Later, as I was leaving the prison and walking back to my car, I realized that one of the reasons I liked being at JCI was that the prison absorbed me in the same way I’d get absorbed in a book. Deep in the world of the prisoners, I’d be temporarily out of touch with my own life. Every time I left the prison and got to the parking lot, my own world would start coming back to me, piece by piece. Back in the wider world of friends, plans, work, and responsibilities, sometimes I didn’t think about the men again until my next trip to the prison. But as soon as I entered its gates, I’d leave my own life behind and return to theirs.

APRIL 17, 2013

For a while, I’d noticed that Guy and Steven hadn’t been on speaking terms. Now they were friendly again, although they weren’t sitting together—which worried me, for Guy’s sake. I thought of him as childlike and vulnerable. He’d once told me he was an orphan. He had a brother somewhere, but the only person who came to visit him regularly was an aunt. I was surprised to learn he was twenty-eight, a few years older than Steven, who seemed by far the more balanced of the two. Physically, Guy looked like an overgrown kid, so tall and skinny that his standard-issue prison jeans were always hanging halfway down his backside in gangsta fashion, revealing his oversized underpants. Like Steven, he could be animated and enthusiastic, but he didn’t have his friend’s intelligence or constitutional optimism, and could fall into fits of inattentive petulance, slouching down in his chair or slumping forward over his tray table with his head on his arms. He was impulsive and impressionable, and could seem naïve and unworldly, with an unguarded interest in things he knew nothing about. He’d often ask me about England, which in Guy’s mind seemed to be a place you visited in a time machine. He wanted to know if it was true, for instance, that the clock face of Big Ben had a hole in the middle through which aristocrats would dump the contents of their chamber pots on the peasants.

One day something I said reminded him that he had a question for me. Reaching into the pocket of his sagging jeans, he pulled out a torn scrap of paper.

“Who’s Guy Fawkes?” he asked me.

“He tried to blow up the House of Lords back in the seventeenth century. He led a group of rebels who planned what they called the Gunpowder Plot. They stockpiled barrels of gunpowder underneath the House of Lords, but the plot was discovered just in time. Why do you ask?”

“I saw this calendar, and on the fifth of November it said ‘Guy Fawkes Night.’”

“The fifth of November is when the plot was discovered. In England, we build fires and have fireworks to celebrate.”

“But you said the plot got discovered, right?”

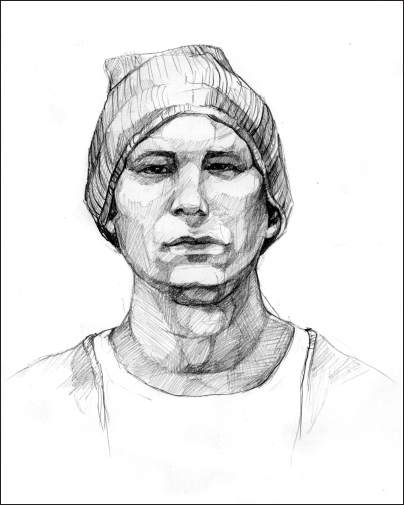

GUY

Illustration of Guy by Jess Bastidas.

“Right.”

“So why do people celebrate him?”

“They celebrate the fact that the plot was discovered and the House of Lords wasn’t blown up.”

“So people didn’t want it to work?”

“Well, no.”

“They didn’t want to blow up all the lords?”

“That’s right.”

“How come?”

“Well, because they ruled the country.”

“But Guy Fawkes must have been a pretty cool dude, right?”

“In some ways, I suppose.”

“And his name, you say it like mine, Guy, right? Not like the French way”—he sneered—“Gee.”

“That’s right.”

Guy put the scrap of paper back in his pocket and swung back in his chair, grinning as happily as if he’d just found out he was the son of a duke.

Like Steven, Guy was a short-timer. I don’t know why he’d been put among the lifers at JCI, but he was expecting to be paroled any day. He’d served four years of an eight-year sentence for drug dealing—a sentence that took into account his prior convictions: theft, the possession of a firearm with a felony conviction, and burglary in the second degree. I found it difficult to imagine this lazy kid as a violent criminal, although he was definitely excitable, and he certainly had a limited attention span. Often, after half an hour of class, he’d rest his head on his folded arms and nod off.

For now, he was alone in this. Even if they didn’t particularly like the story or style, the other men all seemed interested in Burroughs’s descriptions of the guns he’d owned, his accounts of robbing drunks on the New York subway and weaseling morphine scripts out of “croakers.” They were also curious about the kinds of drugs used by Burroughs and his underworld cronies (mainly morphine, heroin, Pantopon, Dilaudid, codeine), and how much they cost. They enjoyed Burroughs’s graphic picture of the physical horrors of drug addiction (uremic poisoning, chronic constipation) and debated the advantages of his various remedies. Burroughs always preferred the incremental “Chinese cure,” a gradual weaning that involved replacing the drug with increasing doses of “Wampole’s Tonic.” In Junkie, he alternates the “Chinese cure” with trips to the U.S. Narcotics Farm in Kentucky, a place where men with drug addictions could voluntarily admit themselves for experimental treatments.

As I left the prison each week, a mass of blue-shirted men would begin crowding toward the chow hall for the first dinner shift. The prisoners came to know the rhythms and dictates of incarceration at a bodily level, and they weren’t alone. Every day, as dinnertime drew near, the resident flock of geese began gathering by the dining hall, pigeons lined the roof of the buildings, and seagulls settled around the Dumpsters. Semi-feral cats emerged from behind the buildings and under the fences, part of a posse that spent its time, like the gulls, between the prison and the nearby fish market just over a mile away.

APRIL 24, 2013

The following week, we were deep in the middle of our discussion about Junkie when J.D. arrived late. J.D. had a Caesar haircut, a cobweb tattooed on his right elbow, and enormous arm muscles, although his legs seemed to be of ordinary size. Maybe he was planning to work on them next. Today, he was also wearing a pair of thick-lensed, black-framed glasses. They gave his face an intellectual expression that made an odd mismatch with his muscular tattooed body.

“Looking smart today, J.D.,” I said as he pulled up a chair. “I didn’t know you wore glasses.”

“I don’t. I hate them,” he grimaced. “I had to wear them. I just got back from court.”

J.D.

Photo of J.D. and Luke by Mark Hejnar.

“Oh?”

“Yeah. I’m trying to get my sentence reduced.”

I’d read about J.D.’s case. It was a tragic one. An only child, he’d quit school after tenth grade and worked full-time to help support his parents. He lived deep in the country, not far from the Delaware state border, with his mother and his grandfather. J.D.’s girlfriend had broken up with him when he was nineteen, and J.D. got caught up in a feud with her new boyfriend. One September evening, after nine months of provocation, J.D. recognized his rival’s pickup truck shining its headlights into his home, and he snapped. He’d been drinking, and he was, as he put it later, “at the end of my rope.” He grabbed his rifle, ran outside, and fired three shots at the pickup truck. The first two shots hit the body of the vehicle, and the third hit the bed of the truck—where, unbeknownst to J.D., a fourteen-year-old boy had been riding. The child was killed instantly.

J.D. had received a life sentence for first-degree murder. He’d served nine and a half years when I met him, five of them at JCI. Now his attorney was trying to get the judge to renegotiate his sentence on the grounds of his good behavior over the last ten years.

“How did it go?” I asked.

“It went very well,” said J.D. firmly.

“So? What did you get?”

“Fifty years,” he said.

If that was good news, I wondered, what would bad news have been? Yet J.D. seemed genuinely thrilled by the outcome. Perhaps, over his ten years in prison, he’d learned to be grateful for small mercies.

“Did you prepare a speech for court?” Vincent asked him.

“I was going to, but then I thought it wouldn’t sound sincere if I just read something off a piece of paper,” J.D. told him. “I thought it would be better to just say whatever came into my mind when I met the victim’s family. But I was under so much pressure, I lost my nerve. I didn’t know what to say.”

“Yeah. That public speaking is a motherfucker,” agreed Donald, a man I could not imagine losing his nerve. I could picture him being intimidating, but never tongue-tied.

“I’m going to appeal again, though,” said J.D. “Maybe we can get it down to forty. Though I’d ask for the death penalty if I could. You know, an eye for an eye.”

I’d always found J.D. hard to read. He was a practicing Christian, and I first got to know him in my writing class, in which he wrote a surprisingly charming paper about elephants. “This story is about one of God’s most beautiful and intelligent creatures, the elephant,” it began. “It is my favorite animal, and I will be telling you why.” It was my first glimpse of J.D.’s boyish, sentimental side, which elicited regular teasing among the men. They made fun of him for getting tearful (though he denied the charge) when, after three months of training, it was time for him to say good-bye to his first service dog, Savoy.

“It’s not true. I wasn’t crying,” J.D. had protested. “I didn’t even go when they came to take him away.”

I didn’t see why J.D. was being so defensive about his attachment to Savoy, although I suppose there’s something to be said for holding back your tears when you live among tough guys. Maybe the men were trying to get him to harden up.

Another time, he wrote a paper about his girlfriend. “I feel truly blessed,” he wrote, “that early in my life I have found the person that I became one flesh with, and I hope to be released soon to spend the rest of my days with my other half.” I was surprised, then—given J.D.’s Christian values—when I learned his “other half” was actually married to somebody else.

“How do you manage to spend so much time on the phone with your girlfriend without her husband getting suspicious?” I asked him one day.

“He drives a truck,” said J.D. “He’s always on the road.”

“Doesn’t he check the phone bill?”

“She’s got unlimited minutes.”

“You really think she’s going to break up with him?”

“Well, I’ve got some ideas,” he said. “Her husband doesn’t like fat girls, so for a while I was trying to persuade her to get fat so he’d divorce her. But she says he won’t divorce her no matter how fat she gets, so now I’ve got to think of something else.”

Sometimes J.D. could be dark and sullen, and whenever he was in a mood like this, the other men always joked that “Sport Coat” was in town. “Sport Coat” was prison slang for the guy who moves in on your girl when you’re away—though as Charles pointed out, if anybody was “Sport Coat” in this situation, it was J.D.

J.D. didn’t think much of Junkie. He told me he subscribed to National Geographic and liked to read things that were “informative” and “taught you something.” Personally, I thought Junkie served these functions, but obviously J.D. felt differently.

I’d always found Junkie a very dark book, but when I’d used it in college classes, my students always found it a breeze. They never considered it scary or disturbing, and many of them told me they found it “an easy read.” I even remember one girl saying that, after finishing Junkie, she’d lent it to her mother, because “she loves that kind of thing.” For whatever reason—and perhaps they just weren’t reading closely—my students weren’t at all fazed by the book’s sleaziest scenes, like that in which Burroughs goes cold turkey in a prison cell. Here, his shattered body, “raw, twitching, tumescent,” lying on a bench, “junk-frozen-flesh in agonizing thaw,” suddenly comes to life when he falls to the floor and the sudden rush of blood to his genitals causes sparks to explode behind his eyes: “the orgasm of a hanged man when the neck snaps.”

Reading Junkie with the prisoners made it seem darker than ever. I was especially struck, this time, by a character named Bill Gains, the son of a bank president, whose “routine” is “stealing overcoats out of restaurants.” “He was not merely negative,” writes Burroughs. “He was positively invisible; a vague respectable presence. There is a certain kind of ghost that can only materialize with the aid of a sheet or other piece of cloth to give it outline. Gains was like that. He materialized in someone else’s overcoat.” Bill Gains seems to be the literal version of a state of mind, a symbolic representation of the pleasure we get from another person’s misery. The worst kind of junk pusher, Gains smiles as he reports on other people’s misfortunes, getting a special kick out of seeing nonusers develop a habit.

Through his portrayal of men like Bill Gains (and Junkie is full of them), Burroughs shows us that caring for each other is not, as most people like to believe, hardwired into our species. It turns out that we’re not naturally social animals. In the junk world, there’s no redemption ever, even in old age, even at the end. Signs of weakness are met with violence. You get older, and things just get worse. At the same time you get used to them. There’s no forgiveness, no place for judgments or opinions, just suffering, struggling human beings. Like Ham on Rye, Junkie is unrelentingly honest. What makes these addicts’ behavior seem so crazy to us is just the situation they’re in. We may not be in their place, but if we were, we may very well act that way too.

But to the prisoners the book was getting “depressing.”

“Of course it’s depressing,” I said, “but that’s what makes it so powerful. You’ve got to give it time. If you concentrate, you can get curious about what makes it depressing, and that’s really interesting. You can get engrossed in it. You need that ‘motivation in the other direction’—one of those things Burroughs says can lead you away from junk.”

What I really wanted to say to them was this: if you pay attention and keep working at it, eventually your eyes will adjust to the darkness, and everything that lives there will be illuminated for you the way things suddenly come into focus when a ray of sunlight breaks into a dark room. You’ve got to keep trying and trying, going back again and again until it grips you, until the world of these addicts starts to seem as meaningful a world as your own. You can’t just give up as soon as it starts to get difficult and uncomfortable. That just means you’ve got to concentrate, try harder, dig in further, work out what’s going on—both in the book and in your head.

I wanted to say it but I didn’t. Everything that day was patchy and disconnected. We kept getting interrupted. Some men turned up late; others left early. People would stick their heads in the room to say hello to their pals, disrupting the discussion. Charles had to leave to go to the commissary. Turk was called to the visiting room. J.D. was in one of his sullen moods (“Sport Coat” was in town). Guy wasn’t there; in fact, I didn’t see him again for six months. He’d been sent to the lockup. Men were sent to the lockup for all kinds of reasons—sometimes they themselves were never told why—but from overhearing the men’s conversation I learned that Guy had been using drugs. I thought of his moodiness, his slumping down in his seat, his nodding off during the discussion. The whole time we’d been reading Junkie, I realized, he’d been high.

In Junkie, Burroughs compares the intense discomfort of withdrawal to the transition from plant back to animal, “from a painless, sexless, timeless state back to sex and pain and time, from death back to life.” While Burroughs can and does stay sober for many months at a time, he always goes back to junk, and in the end you realize that junk will always win out because however awful the nightmare of addiction might be, it’s preferable to the unchanging, desperate boredom of ordinary life. As Burroughs says, you need strong motivations in another direction to resist the pull of junk, and it was hard to imagine Guy being motivated by anything much at all.

How stupid I had been. Junkie contained vivid descriptions of heroin intoxication. I was worried that, by asking him to read the book, I’d played a part in Guy’s relapse.

“We shouldn’t have been reading Junkie,” I realized. “That must have been what sent Guy back to doing drugs.”

Someone snorted with laughter. Guy, the men told me, didn’t go back to doing drugs: he’d been high since he first got to prison. And Junkie had nothing to do with it. No one had seen him so much as open the cover. Now I felt even more foolish. Here I was, claiming literature can give you a reason not to use drugs, then assuming Guy had relapsed and it was literature that had caused it. Literature had nothing to do with it. Drugs can be bought in prison just as they can on the streets, and the boredom and monotony of life behind bars must surely increase the temptation to use.

There are no “dealers” in prison, I learned. Different men get hold of drugs at various times in different ways, and sources change from week to week (if anyone sold them consistently for several days in a row, they’d soon be found out). Some are smuggled in as contraband; some prisoners sell their prescription medications, certain of which could apparently be crushed into a powder and snorted for a quick high. Six hundred milligrams of Neurontin or 75 milligrams of Wellbutrin could be bought for a postage stamp. Guy, I learned, had been using Suboxone, a heroin substitute. His black eye, which he’d blamed on Steven the dog, had actually been the result of an unpaid drug debt. Looking back, it should have been obvious to me—how could a well-trained service dog give his handler a black eye?—but, too busy trying to stimulate the men’s interest in Junkie, I’d failed to notice the presence, right in front of my eyes, of a sleepy, nodding drug addict.

MAY 1, 2013

The cinder-block classroom felt like the inside of an oven. The heat was almost unbearable. I wore a cap-sleeved T-shirt, and to my great annoyance I was turned away at the front gate because “you can’t wear sleeveless.” I got back in my car, drove to the nearby strip mall, grabbed a long-sleeved T-shirt from the Goodwill store—it happened to be Day-Glo pink—and rushed back to the prison. The guys gave me a round of applause when I got to the classroom; still, much of our time had already been lost, and the men didn’t seem to have any interest in discussing Junkie. My T-shirt was too much of a distraction. It hurt their eyes, they said.

“What’s going on?” I asked them. “I thought you all liked this book.”

I noticed Kevin and Sig exchange a look. Finally, Kevin spoke up.

“Yeah, so this guy, whatever his name is. OK, he was married when the book started. What happened to his wife and kids? Seems like he’s turned queer.”

“Good point. He was queer. In fact, he wrote a book called Queer. It’s the companion volume to Junkie. As a matter of fact, I was thinking of asking you to read it next.”

“You’ve got to be kidding me!” exclaimed Kevin. “Nobody in his right mind would walk around prison carrying a book called Queer.”

In the book’s earlier chapters, the men hadn’t enjoyed reading about characters they found despicable—men like Roy the lush worker or Doolie the rat—but these individuals are incidental to Burroughs’s narrative. When they learned that Burroughs himself, despite his marriage, was a self-confessed “queer,” most of them turned away from Junkie, and I was confused and frustrated by their attitude. Later I learned that in the last ten years, JCI had become far more homophobic than it had ever been in the past, when openly gay couples had been commonplace. These days they kept to themselves. Long-timers speculated that the change was caused by the introduction of female COs. These women, rather than other men, were now the primary focus of the prisoners’ sexual attention, even though CO/prisoner relationships were strictly against the rules.

There were no conjugal visits at JCI, and when their wives or girlfriends came to see them, convicts were allowed only a hug when they arrived and another before they left. (Guards stood in the visiting room watching closely to be sure no extra affection was expressed.) Surely there had to be plenty of men at JCI in homosexual relationships. I guessed these were “on the down low.” I wondered whether the most aggressively homophobic men might even be in such relationships themselves. This was especially ironic, I thought, since part of the punishment inherent in the prison system is the way it abolishes the boundary between public and private. Prisoners aren’t supposed to have any secrets. Everything is supposed to be open and transparent. Private tastes and preferences are a luxury of the free.

What particularly depressed me, however, was the prisoners’ apparent inability to imagine people like Roy, Doolie, and Bill having inner lives like their own, tormented by denial and desire. Even more frustrating was the men’s failure to realize that the way they saw the thugs and thieves in Junkie was how most people on the outside saw them. Although I didn’t say so, I’d chosen Junkie because—on the surface at least—it takes as its subject the sordid concerns of a bunch of criminal types who can’t imagine solutions to their problems other than violence. Burroughs shows us, nevertheless, that a limited verbal and even intellectual capacity doesn’t necessarily reflect a diminished inner life, and that social deprivation has no effect on sensitivity to emotional pain. One of the things Junkie reveals is that people never stop struggling and suffering, that lives advance and grow even in the dark, that every history has its personal course. But instead of accepting these fellow victims and recognizing their claim to kinship, the prisoners saw them as unworthy of their time. I thought again of the narrator’s words in “Bartleby”: “So true it is, and so terrible too, that up to a certain point the thought or sight of misery enlists our best affections; but, in certain special cases, beyond that point it does not.”

It wasn’t only the men’s failure to engage with Burroughs that depressed me. There was something else as well. Our discussion about Junkie had reminded me of a moment in Graham Greene’s novel The End of the Affair when the protagonist, an author, suddenly realizes that his writing is “as unimportant a drug as cigarettes to get one through the weeks and years.” Talking to the men about books had made me see very clearly that, for most of the prisoners, reading was just a way of passing time. It wasn’t as expensive or damaging to their physical health as cigarettes or Suboxone would have been but, in the end, perhaps it was just as futile, and without the high.